Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a problem worldwide. Oxidative stress is important factor in beginning and progress of MAFLD. This study is the first clinical trial with the aim of determining the effect of Pistacia atlantica Sub. Kurdica gum on oxidative status in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. In this double-blind randomized clinical trial 50 patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease were randomized into two groups: those given syrup containing Pistacia atlantica sub. Kurdica gum (Group A), those on placebo (Group B). Over a two-month period, Group A given syrup containing 500 mg of P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum per each tablespoon and Group B given syrup without P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum. Anthropometric measures, serum oxidative markers and physical activity were evaluated at the beginning and end of the intervention. We observed a significant decrease in fatty liver grade in group A (P = 0.03). In the end of intervention had not been show significant change in serum total antioxidant capacity (TOS) in group A (P = 0.91) and group B (0.70). Serum total oxidant status (TAC) had been show increase in group A and decrease in group B but this changes not significant as within group (P = 0.36, P = 0.53, respectively) and between group (P = 0.66). The mean of Malondialdehid (MDA) had significant decrease from baseline in group A (P = 0.002) and had non-significant increase in group B (P = 0.65). The between-group comparison of changes of MDA had been show a significant difference (P = 0.025). As well as, after adjusting for baseline characteristics (Age, Gender, Physical activity, BMI), there were not significant differences between A and B groups in the changes comparison of TOS and TAC except for MDA (p < 0.032). Weight had significant decrease in group A (P = 0 < 001). Pistacia atlantica sub. Kurdica gum can improve some oxidative status indices, particularly lipid peroxidation and subsequently MAFLD in patient with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, but further studies with larger samples, longer duration and dose-response assessment will be needed.

Trial registration: IRCT20231219060466N1, 2024-01-05 (https//irct.behdasht.gov.ir/).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by the accumulation of fat in liver cells in the absence of viral infection, alcohol consumption or lipotoxic drugs1,2 and includes a range of diseases from simple steatosis (MAFLD) to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) accompanied by inflammation, ballooning of liver cells and various levels of fibrosis, with a significant risk of progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)3. MAFLD is often associated with metabolic syndrome and is therefore often defined as the hepatic expression of dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity4,5,6.

MAFLD has become the most common chronic liver disease in childhood, adolescence and adulthood7,8,9 and is predicted to be one of the main chronic liver diseases responsible for liver transplantation in adults and children in the future10. MAFLD affects approximately 25–30% of the world’s population, but its prevalence varies significantly in different regions due to genetic and environmental factors and differences in diagnostic methods and criteria. The highest rate is in the Middle East (32%) and South America (30%) and the lowest in Africa (13%). Its prevalence is 24% in North America and Europe and 27% in Asia9,11. Several studies have investigated the prevalence of MAFLD in the Iranian population. Alavian et al.12 reported the prevalence of MAFLD at 1.7% in Iranian children. Another study13 that was conducted on the adult population in Shiraz showed that approximately 21.5% of the general population and 55.8% of patients with type 2 diabetes had MAFLD, which is much more than in East Asian countries14.

The presence of metabolic syndromes, including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, systemic hypertension, and hyperglycemia/diabetes, are commonly associated risk factors for MAFLD. Bilaterally, MAFLD may increase the features and comorbidities of metabolic syndromes15.

Lipotoxicity underlying MAFLD can be explained by the “two-hit” hypothesis16. In the “first hit”, increased intracellular TG accumulation and steatosis occur due to insulin resistance caused by hepatic de novo lipogenesis and impaired fatty acid efflux. During the second hit, MAFLD progresses to MASH by induction of cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1(CYP2E1)17, which increases intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) that increase oxidative stress to facilitate inflammation and cell death. In addition, “third hit”/“multiple hits” hypotheses have also been reported, in which excessive oxidative stress causes cell death and reduced proliferation of mature hepatocytes, and eventually liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)18.

MAFLD has been raised as a big challenge due to its prevalence, diagnostic problems, the complexity of its pathogenesis, and the lack of specific treatments. Lifestyle modification and dietary restrictions are considered the primary non-interventional treatment for MAFLD9.

In recent years, natural plant metabolites have been considered as compounds for alternative treatments in various diseases19. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 65% of the world’s population uses herbs and traditional medicine as a complementary method in health care20. The Pistacia genus belongs to the Anacardiaceae family, which includes approximately 70 genera and more than 600 species21. Species of the Pistacia are evergreen, aromatic, resinous shrubs that reach 8 to 10 m in height22. The chemical composition of Pistacia components, including leaves, fruit, stem, gum and volatile essential oil, has been identified and is used to treat various human diseases due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, and cytoprotective/antigenotoxic properties, it has been investigated in animal and clinical studies23,24,25,26,27.

Pistacia atlantica Sub. Kurdica, known as Daraban or Qazwan in Kurdish and Baneh in Persian28, is a medicinal and food plant that grows natively in western Iran29. This subspecies has gum, which is known as mastic gum, an oleoresin that is obtained as a secreted substance from the trunk, stem and branches30.

Pistacia atlantica sub. Kurdica gum has a long history as a therapeutic agent with many pharmacological and biological properties31 and contains volatile oil - αpinene, sabinene and limonene as main components and many other compounds32 which have antimicrobial33, anti-inflammatory34 antioxidant35,36, and hypoglycemic24,37,38 properties. Also, in animal studies, the positive effects of Pistacia atlantica on improving the function and histological structure of the liver39,40,41,42, and improving oxidative stress markers and enzymes43,44,45,46,47 have been confirmed due to these antioxidant, anti-inflammatory compounds and improvement of antioxidant activity and total antioxidant capacity (TAC)48. The protective and therapeutic effects of Pistacia atlantica sub. Kurdica gum is due to the presence of flavonoids and phenolic compounds49.

Considering the increasing prevalence of MAFLD and its numerous clinical complications, this disease has recently become one of the liver diseases of interest. As mentioned, oxidative stress plays a key role in the initiation of MAFLD, its progression to MASH and subsequently liver fibrosis and cirrhosis due to continuous liver damage due to excessive production of ROS and inflammation caused by various endogenous and exogenous injuries. Several herbal drugs with antioxidation purposes have been tested, but due to conflicting results none of them have been approved for clinical use.

Different parts of Pistacia atlantica sub. Kurdica has been studied as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective in various metabolic conditions in animal study and its positive effects have been observed, but so far no clinical trial has been conducted regarding its effect on oxidative status especially total antioxidant capacity and total oxidative status (TOS) and hepatprotective effect in people with MAFLD. Therefore, this study is the first clinical trial with the aim of determining the effect of Pistacia atlantica Sub. Kurdica gum on oxidative status in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.

Materials & methods

Study design

This randomized, double-blind clinical trial was conducted from December 2023 to April 2024 on patients who had been diagnosed as MAFLD. The sample size by use comparing two community formula and according to the results of a previous study50 with 80% power and 5% significance was computed (21 sample per group). The final sample size, considering 20% withdraw of participants, was 25 people per group. The study and its objectives were fully and clearly explained to the participants prior to participation, and informed consent was obtained. The trial was given ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the Deputy of Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (ethics approval number: IR.KUMS.REC.1402.442) and adheres to CONSORT guidelines.

Participants, recruitment and randomization

Participants were selected from people who had been referred to the ultrasound centers for liver fatty screening. Initially medical files were assessed for 250 people who are diagnosed with fatty liver. From this pool, 63 people were enrolled in the study based on several inclusion criteria: 18–60 years old; Fatty liver grade in range of 1, 1 to 2, 2 and 2 to 3 based on ultrasound diagnosis51; BMI in the range of 25–35 kg/m2. The conditions for not entering the study include: the presence of secondary causes of hepatic steatosis (such as hepatitis B and C virus, autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, celiac disease, pituitary hypo function, hypothyroidism, Wilson’s disease, abthallipoproteinemia or corticosteroid drugs), suffering from diseases such as Autoimmune, digestive, liver diseases (fibrosis, cirrhosis, HCC), kidney, thyroid and cardiovascular diseases, severe respiratory disease (asthma and chronic bronchitis), pregnancy, breastfeeding, alcohol consumption and smoking, consumption of plant sterols, psyllium and oil Fish, consumption of any kind of vitamins and minerals, food supplements and finally the existence of allergy to all kinds of Pistacia species. To confirm and exact determine fatty liver grade, subjects were referred to the Imam Reza Hospital (affiliated with the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences), where them were evaluated by an ultrasound expert. And finally 53 persons were confirmed, of whom 50 were randomly allocated into two groups: those receiving syrup containing P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum (Group A); those receiving placebo syrup (Group B) (Fig. 1).

A random sequence was generated by using the random block method using a random block of 4 for a total of 12 blocks using the website https://www.sealedenvelope.com.The person who collected the information was unaware of the type of allocation of the samples to the study groups. The following things were considered regarding the implementation of the random assignment process: (a) One English letter was assigned to each of the groups: A to the supplement group, B to the placebo group. (b) A sequence was created for a sample size of 46. (c) For the concealment process of random allocation, 46 non-transparent envelopes and 46 cards (total sample size) was prepared. Inside each envelope, 4 cards were placed in the order of the sequence in each block. Block numbers was written on each envelope. The name of the desired group was written on each card in sequence. Due to the fact that people do not know about the random sequence and the considered blocks, random allocation concealment was observed and before the allocation of the individual, the allocated group was not clear.

Intervention

Every 15 days Group A participants were given bottles of 250 cc syrup containing 500 mg of P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum per each tablespoon and Group B participants were given bottles of 250 cc syrup without P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum. To ensure that the subjects would consume the syrup, both groups received a form on which they could record their consumption over 15 days. We asked them to consume the two tablespoons of syrup after breakfast and dinner and bring the empty bottle back to us. as well as, through face-to-face and phone interview about the how to take, observed side effects, and willingness to continue cooperation, we obtained assurances about compliance with the consumption of the prescribed amounts. Intake dose of P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum (2000 mg/day) was determined based on human equivalent dose (HED)52. The duration of the intervention for this study was two months.

Production of syrup

The production of the syrup containing gum was carried out by the Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Company (Kashan, Iran). Each 250 cc of syrup contained, 5.5% gum, 5.5% sunflower oil, 2% starch, 5% sugar, 0.1% sucralose, 80.7% water, 0.8% methyl paraben, 0.02% propyl paraben and 1% alcohol. The placebo was identical except for the lack of gum.

Demographic information

Data about age, gender, duration of disease and medical history was collected using a demographic questionnaire.

Anthropometric indices

Weight, body mass index (BMI) and body fat with minimal clothing were measured using bioelectric impedance (Body Analyzer 333 PlusAvis). Height was measured using a stadiometer with an accuracy of 0.1 cm in standard mode (without shoes and with the shoulders, hips, and heels in contact with the wall).

Biochemical indices

Serum TAC, TOS and malondialdehyde (MDA) was assessed by commercial kit (Kiazist, Life Sciences, Iran). TAC assay was based on the reduction of Cu+ 2 by plasma antioxidants to Cu+ 1 in the presence of a chromogen reagent to produce a colored complex which is measured at 450 nm. Serum TAC value was estimated by reference to Trolox standard curve. The results are reported as nmol of trolox equivalent/mL. Serum TOS was assessed based on the ability of change ferrous ions (Fe III) to ferric ions (Fe II) and produce color in the presence of chromogen. This color had a wavelength of 550–580 nm. The reaction between ferric ions and xylenol orange forms a colored complex. The assay was calibrated using H2O2. The amount of absorption was directly related to the amount of oxidant, and the standard curve was drawn in the presence of H2O2.

Lipid Peroxidation marker; MDA was measured according to the forming complex of MDA and thiobarbituric acid that was absorb at a wavelength of 532 nm.

Diet

All patients were advised to adhere of diet with reduced calorie (~ 250 Kcal/day) containing 30% calorie from fat, 52% from carbohydrate, and 18% from protein.

Physical activity

Physical activity before and after the intervention was assessed by the use of the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire which includes seven questions related to physical activity associated with work, homework and leisure time during the past seven days. Total metabolic equivalent of task (hours per week) was calculated. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire had previously been confirmed in Iran53.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD and the qualitative variables as frequency (number and percent). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of quantitative data. To compare the normal and non-normal variables between the groups, independent sample T-test and the U Mann-Whitney were used, respectively. Also, to compare changes within groups for the normal and non-normal variables, the paired samples t-test and Wilcoxon test were applied, respectively. To adjust for the baseline characteristics, the Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) test, was used. To compare the qualitative variables in the two groups, the chi-square test (Fisher exact test) and Kruskal-Wallis test were used. Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 20. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Fifty individuals were enrolled in the study, although over the course of the intervention four were excluded (two because of not wanting to continue the study, one due to lack of adherence to consuming the specified amounts of syrup, one due to sensitivity to syrup and feeling nausea (Fig. 1). Ultimately, 46 participants (20 females and 26 males, with an average age of 44.57 ± 8.57 years) completed the study. Adherence to the study was 98% for all 46 participants.

As Table 1 shows, there were no significant differences among the basic characteristics of the two groups, including age (P = 0.64), distribution of gender (P = 0.07), grade of fatty liver (P = 0.13), duration of disease (P = 0.95) and anthropometric measurements including weight (P = 0.48), BMI (P = 0.64), and Body fat (P = 0.77).

After the two-month intervention we observed a significant change in grades of fatty liver in Group A (Wilcoxon, z = -2.106, P = 0.035), but changes are not significant in Group B (Wilcoxon, z = -1.414, P = 0.157) (Table 2).

Physical activity level had no significant difference in between groups A and B before and after intervention (P = 0.72, P = 0.78 respectively). As well as, mean of within group changes not significant in group A (P = 0.08) and group B (P = 0.56).

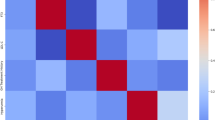

The mean of TOS, TAC and MDA had no between groups significant difference the before of intervention (P = 0.37, P = 0.91, P = 0.07, respectively) (Table 3).

At the end of intervention had not been show significant change in serum level of TOS in group A (P = 0.91) and group B (P = 0.70). Serum level of TAC had been show increase in group A and decrease in group B but this changes was not significant as within group (P = 0.36, P = 0.53, respectively) and between group (P = 0.66).

The mean of MDA had significant decrease from baseline in group A (P = 0.002) and had non-significant increase in group B (P = 0.65). The between-group comparison of changes of MDA had been show a significant difference (P = 0.025) (Table 3).

At the end of the intervention, the mean weight and BMI in group A were significantly decrease from baseline (p < 0.001, P = 0.001). Between group comparison of changes of weight had been show a significant differ (P = 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the results of between-group comparisons using the MANCOVA test for TAC, TOS and MDA adjusting for baseline characteristics. After adjusting for baseline characteristics (Age, Gender, Physical activity, BMI), there were not significant differences between A and B groups in the changes comparison of TOS and TAC except for MDA (p < 0.032).

The participants except one in placebo group (with feeling nausea) had no complaints about consuming the syrup.

Discussion

Metabolic dysfunction‑associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a problem worldwide, including in Iran13,54,55. Based on epidemiological evidence, MAFLD is not only associated with an increased risk of liver-related complications, but also increases the risk of several extrahepatic diseases56, including adverse cardiovascular57 and renal58 outcomes, type 2 diabetes, and some common endocrine diseases56. Treatment of MAFLD for many people is a difficult and exhausting task, which makes complications more likely to develop59,60,61. At present, there is no approved pharmacological treatment for MAFLD62 and the current proposed treatments for are summarized under the categories of lifestyle, bioactive compounds and medicines63.

Use herbal product that has been noticed traditionally and in vitro and in vivo studies due to its special bioactive compounds is Pistacia atlaantica35,36, but so far no human study has investigated the role of this plant species in the improvement and treatment of MAFLD, and our study is the first clinical trial in this field.

The results of our study showed that after two months of intervention, 70.84% of patients in group A had a decrease in the grade of fatty liver, the decrease in the grade of fatty liver was observed in only 18.2% of patients in group B, and in 77.27% of them was unchanged. Also, 8.3% of group A patients were non-MAFLD at the end of the study, and 4.53% of patients in group B, fatty liver grade was increased. Considering that the patients of both groups A and B had the same diet with energy reduction of 250 kcal per day, the significant reduction of fatty liver grade in patients of group A can be attributed to the consumption of syrup containing P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum.

What factors cause the accumulation of fat in the liver tissue and its progression to cirrhosis and more advanced stages are not precisely known, but there are some important proposed mechanisms in this pathway, which include lipotoxicity caused by oxidative stress, which cause fat accumulation in tissues outside of adipose tissue, including liver tissue and following activation of intracellular inflammatory pathways and its more advanced stage16,17,18.

Plant-based antioxidants as naturally occurring antioxidants can be used to protect human beings from oxidative stress damage64,65. P. atlantica subspecies are known as an excellent source of natural antioxidants which contribute to the daily diet66,67.

Many studies have evaluated the antioxidant potential of different extracts from P. atlantica DPPH-based radical scavenging, ABTS•+ radical scavenging, nitric oxide scavenging, reducing power, and β-carotene bleaching tests have been employed for this assessment, that exhibited antioxidant activity of P. atlantica subspecies68,69.

Several studies66,70,71 revealed that P. atlantica sub. kurdica contains phenolic compounds and terpenes with antioxidant properties, which are likely to be responsible for the pharmacological effects. The phenolic compounds of P. atlantica Desf. galloylquinic acid, quinic acid, gallic acid, glucogallin and trigalloylglucose showed antioxidant activities66.

In our study after two-month intervention was not show any change in serum level of TOS. although TAC in group A had increased and this increase was not observed in group B, but the mean of changes of TAC between groups A and B did not differ significantly.

Gismondi., et al.48 in a study aimed at investigating the nutritional content and biological properties of different parts of Pistacia atlantica Desf, antioxidant activity and total antioxidant capacity were investigated and the results showed the samples revealed interesting antioxidant activity and total antioxidant capacity.

Hosseini et al.,72 in a study aimed at examining the effect of extract and essential oils of P. atlantica in streptoosotocin diabetic mice showed that the administration of P. atlantica extract for three consecutive weeks increased TAC and reduced lipid peroxidation and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).

Tanideh, et al. in animal study evaluated the effect of Pistacia atlantica hydro alcoholic extract with bone marrow- derived stem cells on induced knee osteoarthritis in rat and results had been show injective extract of Pistacia atlantica can be significantly increased serum level of TAC and decreased TNF-α as an inflammatory marker after 12-week and be effective in knee cartilage repair44.

The mean of MDA level in group A had a significant decrease at the end of the study (46.57 ± 27.13 vs. 27.69 ± 16.58) but in group B had a significant increase (34.02 ± 24.82 vs. 49.56 ± 59.59). The difference in MDA changes between groups A and B, is showing the effect of syrup containing P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum in reduction of MDA level probably due to the its anti-oxidative effects. The persistence of this significant between-group difference after adjustment for baseline characteristics strengthened these results.

Bagheri et al., investigated the effect of 200 mg/kg/day Pistacia atlantica oleoresin on markers of oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes in diabetic rats, and the results showed that Pistacia atlantica oleoresin significantly reduced MDA as a marker of oxidative stress (54.59 ± 12.54 vs. 69.92 ± 3.92) and increased antioxidant enzymes include Glutathione (GSH) (4.5 ± 0.89 vs. 2.57 ± 0.40), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) (25.8 ± 3.8 vs. 11.66 ± 2.2), catalase (CAT) (22.69 ± 0.36 vs. 12.17 ± 3.8), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (3.65 ± 1.08 vs. 0.78 ± 0.67), which showed Pistacia atlantica oleoresin can be suggested as a factor to protect against diseases related to oxidative stress45.

Benahmad et al.,46 investigated the hepatoprotective effect of 150 mg/kg/day aqueous extract of Pistacia atlantica Desf during 32 day against oxidative stress caused by mercury chloride toxicity in the liver of male rats and was observed aqueous extract of Pistacia atlantica modify the toxic effects of mercury by improving some disturbances include decrease of thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) are a marker of lipid peroxidation, reflecting a pro-oxidative effect and increase of liver glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity. Results show that the administration of P. atlantica aqueous extract is a good extract with very promising therapeutic value for the treatment of liver damage.

In an animal study47 to determine the effects of 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg hydroalcoholic extract of Pistacia atlantica in a 90-day prevention and 30-day treatment period on the plasma levels of MDA, GST, Catalase, SOD, GSH in rats fed with high-fat diet, the results indicated a decrease in level plasma of MDA, and an increased in levels plasma of catalase and SOD in the treatment group with 400 mg/kg pistachia atlantica.

In a study73 aimed to investigate the effect of oral administration of 300 mg/ml and 600 mg/ml fruit oil and 10% and 20% Pistacia atlantica enema gel on the treatment of experimentally induced colitis in a rat model, macroscopic tests, Histopathology and MDA measurement showed that a dose of 600 mg of Pistacia atlantica fruit oil extract orally and 20% rectal gel can reduce MDA levels and prevent colitis from Improve the physiological and pathological opinion in mouse model and be effective for ulcerative colitis.

Different parts of P. atlantica subspecies have been found to exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective activities. P. atlantica sub. kurdica gum contains phenolic and flavonoid compounds with antioxidant properties, which are to be responsible for the pharmacological effects74, on the other hand, this plant is completely organic and no poison or fertilizer is used in its growth and exploitation process.

In this study we presented for all patient a diet with reduced energy intake (250 kcal/day) during 2 months of intervention and results have been shown a significant decrease of weight only in group A that can be due to effect of P. atlantica components on inhibiting α-amylase and α-glucosidase which can cause a decrease in carbohydrate digestion and subsequent weight loss. As well as, P. atlantica components can be activatePeroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPAR-γ) and Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-α)75,76 that be attributed to the increased lipid metabolism and subsequent weight loss. our study was shown a non-significant decrease in body fat of group A and a non-significant increase in body fat of group B that may be due to short duration of intervention. Decrease in body fat probably due to mentioned mechanism for effect of P. atlantica components on activating PPAR-γ and PPAR-α.

In study of Jamshidi et al.,77 metabolic syndrome induced rats by fructose had significant weight increases, but the groups receiving P. atlantica sub. Mutica oils had lower increases in weight than the fructose group. The effects of P. atlantica sub. mutica oils in this relation may be attributed to the increased lipid metabolism by activation of PPAR-α by containing of oleic acid of P. atlantica sub. mutica75.

Despite the efficacy of P. atlantica sub. Kurdica as an antioxidant foodstuff and complementary treatment in improving MAFLD and its safety in MAFLD patients, there were some limitations in the present study which include short intervention period, the few numbers of patients and lack of dose response assessment of P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum.

Conclusion

Considering that the consumption of syrup containing P. atlantica sub. Kurdica gum for two month has been able to have a positive effect in improving some oxidative indices, particularly lipid peroxidation and subsequent MAFLD, it is suggested that clinical trials be conducted in different population in terms of health, the long duration of the intervention, as well as a larger sample size and dose-response interventions to achieve more comprehensive results to recommend the use of this herbal substance as an alternative or complementary treatment along with other MAFLD treatment strategies.

Data availability

Data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- CYP2E1:

-

Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- GPX:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- GST:

-

Glutathione S-transferase

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehid

- MAFLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction‑associated fatty liver disease

- MANCOVA:

-

Multivariate analysis of covariance

- MASH:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcohol fatty liver disease

- PPAR-α:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- alpha

- PPAR-γ:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- gamma

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TBARS:

-

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance

- TAC:

-

Total antioxidant capacity

- TOS:

-

Total oxidant status

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

Arroyave-Ospina, J. C., Wu, Z., Geng, Y. & Moshage, H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for prevention and therapy. Antioxidants 10 (2), 174 (2021).

Eslam, M. et al. The Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hep. Intl. 19 (2), 261–301 (2025).

Sheka, A. C. et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a review. Jama 323 (12), 1175–1183 (2020).

Marjot, T., Moolla, A., Cobbold, J. F., Hodson, L. & Tomlinson, J. W. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: current concepts in etiology, outcomes, and management. Endocr. Rev. 41 (1), 66–117 (2020).

Wattacheril, J. & Sanyal, A. J. Lean NAFLD: an underrecognized outlier. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 15, 134–139 (2016).

Younes, R. & Bugianesi, E. A spotlight on pathogenesis, interactions and novel therapeutic options in NAFLD. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 (2), 80–82 (2019).

Fitzpatrick, E. & Dhawan, A. Childhood and adolescent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: is it different from adults? J. Clin. Experimental Hepatol. 9 (6), 716–722 (2019).

Nobili, V. et al. NAFLD in children: new genes, new diagnostic modalities and new drugs. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 (9), 517–530 (2019).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64 (1), 73–84 (2016).

Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 15, 1–6 (2017).

Bellentani, S. The epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 37, 81–84 (2017).

Alavian, S. M., Mohammad-Alizadeh, A. H., Esna‐Ashari, F., Ardalan, G. & Hajarizadeh, B. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease prevalence among school‐aged children and adolescents in Iran and its association with biochemical and anthropometric measures. Liver Int. 29 (2), 159–163 (2009).

Lankarani, K. B. et al. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease in Southern Iran: A population based study. Hepat. Mon. 13(5) (2013).

Li, H. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in chengdu, Southwest China. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. International: HBPD INT. 8 (4), 377–382 (2009).

Friedman, S. L., Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A., Rinella, M. & Sanyal, A. J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 24 (7), 908–922 (2018).

Day, C. P. & James, O. F. Steatohepatitis: A Tale of Two Hits??. 842–845 (Elsevier, 1998).

Aljomah, G. et al. Induction of CYP2E1 in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 99 (3), 677–681 (2015).

Peng, C., Stewart, A. G., Woodman, O. L., Ritchie, R. H. & Qin, C. X. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a review of its mechanism, models and medical treatments. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 603926 (2020).

Kazemi, M., Eshraghi, A., Yegdaneh, A. & Ghannadi, A. Clinical Pharmacognosy-A New Interesting Era of Pharmacy in the Third Millennium. 1–3 (Springer, 2012).

Sharifi, M. S. & Hazell, S. L. Isolation, analysis and antimicrobial activity of the acidic fractions of mastic, kurdica, mutica and Cabolica gums from genus Pistacia. Global J. Health Sci. 4 (1), 217 (2012).

Douissa, F. B. et al. New study of the essential oil from leaves of Pistacia lentiscus L.(Anacardiaceae) from Tunisia. Flavour Fragr. J. 20 (4), 410–414 (2005).

Aghaei, P., Bahramnejad, B. & Mozafari, A. Effect of different plant growth regulators on callus induction of stem explants in ‘Pistacia atlantica’ subsp. Kurdica. Plant. Knowl. J. 2 (3), 108–112 (2013).

Bhouri, W. et al. Study of genotoxic, antigenotoxic and antioxidant activities of the digallic acid isolated from Pistacia lentiscus fruits. Toxicol. In Vitro. 24 (2), 509–515 (2010).

Hamdan, I. & Afifi, F. Studies on the in vitro and in vivo hypoglycemic activities of some medicinal plants used in treatment of diabetes in Jordanian traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 93 (1), 117–121 (2004).

Remila, S. et al. Antioxidant, cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of Pistacia lentiscus (Anacardiaceae) leaf and fruit extracts. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 7 (3), 274–286 (2015).

Taran, M., Mohebali, M. & Esmaeli, J. In vivo efficacy of gum obtained pistacia atlantica in experimental treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Iran. J. Public. Health. 39 (1), 36–41 (2010).

Tassou, C. C. & Nychas, G. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of mastic gum (Pistacia lentiscus var. chia) on gram positive and gram negative bacteria in broth and in model food system. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 36 (3–4), 411–420 (1995).

Dyary, H. O., Rahman, H. S., Othman, H. H., Hassan, S. M. A. & Abdullah, R. Acute toxicity of Pistacia atlantica green seeds on Sprague-Dawley rat model. J. Zankoy Sulaimani. 19 (3–4), 9–16 (2017).

Amin, G. Medicinal Plants of Iran (Tehran University Publication, 2005).

Dogan, Y., Baslar, S., Ayden, H. & Mert, H. H. A study of the soil-plant interactions of Pistacia lentiscus L. distributed in the Western Anatolian part of Turkey. Acta Bot. Croatica. 62 (2), 73–88 (2003).

Demirci, F., Baser, K., Calis, I. & Gokhan, E. Essential oil and antimicrobial evaluation of the Pistacia Eurycarpa. Chem. Nat. Compd. 37, 332–335 (2001).

Magiatis, P., Melliou, E., Skaltsounis, A-L., Chinou, I. B. & Mitaku, S. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of Pistacia lentiscus var. Chia. Planta Med. 65 (08), 749–752 (1999).

Sharifi, M. S. & Hazell, S. L. GC-MS analysis and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of the trunk exudates from Pistacia atlantica Kurdica. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 3 (8), 1364 (2011).

Sharifi, M. S. Fractionations and analysis of trunk exudates from Pistacia genus in relation to antimicrobial activity. (2006).

Bahmani, M. et al. The effects of nutritional and medicinal mastic herb (Pistacia atlantica). J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 7 (1), 646–653 (2015).

Tolooei, M. & Mirzaei, A. Effects of Pistacia atlantica extract on erythrocyte membrane rigidity, oxidative stress, and hepatotoxicity induced by CCl4 in rats. Global J. Health Sci. 7 (7), 32 (2015).

Hashemnia, M., Nikousefat, Z. & Yazdani-Rostam, M. Antidiabetic effect of Pistacia atlantica and amygdalus scoparia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 24, 1301–1306 (2015).

Kasabri, V., Afifi, F. U. & Hamdan, I. In vitro and in vivo acute antihyperglycemic effects of five selected Indigenous plants from Jordan used in traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 133 (2), 888–896 (2011).

Hussein, S. A. A., El-Mesallamy, A., Othman, S. O., Soliman, A. M. M. & Erratum: Identification of novel polyphenolic secondary metabolites from Pistacia Atlantica desf. And demonstration of their cytotoxicity And CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity in rat. Egypt. J. Chem. 63 (12), 117–130 (2020).

Norasteh, H., Mohammadi, S., Nikravesh, M. & Taraz Jamshidi, S. Protective effect of Bene (Pistacia atlantica) on busulfan-induced renal-liver injury in laboratory mice. J. Babol Univ. Med. Sci. 22 (1), 17–23 (2020).

Ha, O., He, O. & Badi, H. N. The effect of Pistacia atlantica nut powder on liver phosphatidate phosphohydrolase and serum lipid profile in rat. (2008).

Farzanegi, P., Ghanbari-Niaki, A., Mohseni, A. & Haghayeghi, M. Pistacia Atlantica extract enhances Exercise-Mediated improvement of antioxidant defense in Vistar rats. Annals Appl. Sport Sci. 2 (2), 13–22 (2014).

Hosseini, S. et al. Antihyperlipidemic and antioxidative properties of Pistacia atlantica subsp. Kurdica in Streptozotocin-Induced diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 13, 1231–1236 (2020).

Borzooeian, G. et al. Evaluation the effect of Pistacia atlantica hydro alcoholic extract with bone marrow-derived stem cells on induced knee osteoarthritis in rat. Iran. J. Orthop. Surg. 14 (1), 30–41 (2020).

Bagheri, S. et al. Effects of Pistacia atlantica on oxidative stress markers and antioxidant enzymes expression in diabetic rats. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 38 (3), 267–274 (2019).

Benahmed, F. et al. Protective effect of Pistacia atlantica Desf leaves on mercury-induced toxicity in rats. South. Asian J. Exp. Biol. 10(3) (2020).

Rouhi-Boroujeni, H. et al. Extract of Pistacia atlantica L. on hyperlipidemia and biomarkers of oxidative stress in rats fed a high-fat diet and hypoglycemic effect in diabetic rats induced with alloxan.

Belyagoubi-Benhammou, N. et al. Nutraceutical content and biological properties of lipophilic and hydrophilic fractions of the phytocomplex from Pistacia atlantica desf. Buds, roots, and fruits. Plants 13 (5), 611 (2024).

Rahman, H. S. Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant and anticancer activities of mastic gum resin from Pistacia atlantica subspecies Kurdica. OncoTargets Ther. 4559–4572 (2018).

Seyyedebrahimi, S., Khodabandehloo, H., Nasli Esfahani, E. & Meshkani, R. The effects of Resveratrol on markers of oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Acta Diabetol. 55, 341–353 (2018).

Araújo, A. R., Rosso, N., Bedogni, G., Tiribelli, C. & Bellentani, S. Global epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis: what we need in the future. Liver Int. 38, 47–51 (2018).

Nair, A. B. & Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic. Clin. Pharm. 7 (2), 27–31 (2016).

Moghaddam, M. B. et al. The Iranian version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) in iran: content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl. Sci. J. 18 (8), 1073–1080 (2012).

Eslam, M. et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 73 (1), 202–209 (2020).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 71 (4), 793–801 (2019).

Wong, V. W. S., Ekstedt, M., Wong, G. L. H. & Hagström, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 79 (3), 842–852 (2023).

Pan, Z., Shiha, G., Esmat, G., Méndez-Sánchez, N. & Eslam, M. MAFLD predicts cardiovascular disease risk better than MASLD. Liver International: Official J. Int. Association Study Liver. 44 (7), 1567–1574 (2024).

Pan, Z. et al. MAFLD criteria are better than MASLD criteria at predicting the risk of chronic kidney disease. Ann. Hepatol. 29 (5), 101512 (2024).

Ballestri, S. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with an almost twofold increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 31 (5), 936–944 (2016).

Mantovani, A. et al. Complications, morbidity and mortality of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 111, 154170 (2020).

Powell, E. E., Wong, V. W. S. & Rinella, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet 397 (10290), 2212–2224 (2021).

Petroni, M. L., Brodosi, L., Bugianesi, E. & Marchesini, G. Management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ 372 (2021).

Sun, J., Jin, X. & Li, Y. Current strategies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease treatment. Int. J. Mol. Med. 54 (4), 88 (2024).

Sarangarajan, R., Meera, S., Rukkumani, R., Sankar, P. & Anuradha, G. Antioxidants: friend or foe? Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 10 (12), 1111–1116 (2017).

Lobo, V., Patil, A., Phatak, A. & Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 4 (8), 118 (2010).

Ahmed, Z. B. et al. Antioxidant activities of Pistacia atlantica extracts modeled as a function of chromatographic fingerprints in order to identify antioxidant markers. Microchem. J. 128, 208–217 (2016).

Ahmed, Z. B. et al. Defining a standardized methodology for the determination of the antioxidant capacity: case study of Pistacia atlantica leaves. Analyst 145 (2), 557–571 (2020).

Toul, F., Belyagoubi-Benhammou, N., Zitouni, A. & Atik-Bekkara, F. Antioxidant activity and phenolic profile of different organs of Pistacia atlantica desf. Subsp. atlantica from Algeria. Nat. Prod. Res. 31 (6), 718–723 (2017).

Rezaie, M., Farhoosh, R., Sharif, A., Asili, J. & Iranshahi, M. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of Bene (Pistacia Atlantica subsp. mutica) hull essential oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 6784–6790 (2015).

Ghaderi, A. & Ebrahimi, B. Soxhlet extraction and gas chromatography mass spectrometry analysis of extracted oil from Pistacia atlantica Kurdica nuts and optimization of process using factorial design of experiments. Sci. J. Anal. Chem. 3 (6), 122–126 (2015).

Ben Ahmed, Z. et al. Seasonal, gender and regional variations in total phenolic, flavonoid, and condensed tannins contents and in antioxidant properties from Pistacia atlantica ssp. Leaves. Pharm. Biol. 55 (1), 1185–1194 (2017).

Hosseini, S. et al. Antihyperlipidemic and antioxidative properties of Pistacia atlantica subsp. Kurdica in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 1231–1236 (2020).

Tanideh, N. et al. Healing effect of pistacia atlantica fruit oil extract in acetic Acid-induced colitis in rats. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 39 (6), 522 (2014).

Ben Ahmed, Z. et al. Four Pistacia atlantica subspecies (atlantica, cabulica, Kurdica and mutica): A review of their botany, ethnobotany, phytochemistry and Pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 265, 113329 (2021).

Assy, N., Nassar, F., Nasser, G. & Grosovski, M. Olive oil consumption and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 15 (15), 1809–1815 (2009).

Georgiadis, I., Karatzas, T., Korou, L. M., Katsilambros, N. & Perrea, D. Beneficial health effects of Chios gum mastic and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: indications of common mechanisms. J. Med. Food. 18 (1), 1–10 (2015).

Jamshidi, S., Hejazi, N., Golmakani, M. T. & Tanideh, N. Wild pistachio (Pistacia Atlantica mutica) oil improve metabolic syndrome features in rats with high Fructose ingestion. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 21 (12), 1255–1261 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants involved in our study and Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Company (Kashan, Iran) for their assistance with the production of syrup.

Funding

This study was supported by the Deputy of Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (Grant ID: 4020843).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM, SMN, AS, NJ, LB conducted the study design. RM, SR, ZGh collected the data. MGS conducted ultrasound test for assessment of NAFLD. RM, BM performed the statistical analysis. RM wrote drafted of the manuscript. SMN and AS critically read the manuscript. All authors approved the the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article is taken from student Ph.D. thesis. The trial was given ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the Deputy of Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (ethics approval number: IR.KUMS.REC.1402.442) and registered with the Iranian Clinical Trials Registry (registration number IRCT: IRCT20231219060466N1). Informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mostafaei, R., Nachvak, S.M., Saber, A. et al. Pistacia atlantica can improve oxidative status in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 15, 32947 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04107-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04107-z