Abstract

Light is crucial for understory sapling regeneration, and understanding leaf functional traits (LFT) is key to saplings’ adaptation to different light conditions. Currently, how LFT vary with light quality heterogeneity is not well understood. This study aims to assess canopy-induced light heterogeneity and the adaptive strategies of larch saplings to it. The study classified the light environments of larch saplings into three types based on red-to-blue light ratios: 0.6R:1B, 1.2R:1B, and 1.5R:1B. As canopy openness (CO) increases and leaf area index decreases, the proportion of red light in the understory gradually rises. Saplings under the highest CO with a 1.5R:1B had lower leaf area but higher leaf dry matter, starch, carbon, and potassium contents. Metabolite analysis revealed that, under 1.5R:1B light conditions, the upregulation of sucrose synthase (SS) and sucrose-phosphate synthase (SPS) enzyme activities accelerated the consumption of maltose in leaves, led to the accumulation of ribitol and d-glucitol, and increased the levels of organic acids, thereby promoting the accumulation of flavonoids. These findings suggest that 0.6R:1B favors a resource acquisition strategy (rapid growth), while 1.5R:1B leans towards a resource conservation strategy (slow growth). This study provides a new perspective on the effects of light conditions on understory vegetation regeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In forest ecosystems, light stands as the paramount environmental factor influencing plant growth and competition1. The availability of light to seedlings largely determines their success in establishing within the forest2. The forest canopy influences the growth, biomass allocation, and regeneration of understory seedlings through processes such as light absorption, transmission, and reflection3. When sunlight enters the canopy, it is weakened by absorption and reflection, resulting in spatial heterogeneity in light quality4. For example, Wei et al. (2019) pointed out that variations in canopy characteristics can lead to differences in spectral composition among different forest types5. Furthermore, Hertel et al. (2012) conducted research in mixed beech and spruce forests, revealing a significant negative correlation between leaf area index (LAI) and the blue light (B, 400–500 nm)/red light (R, 600–700 nm)6. Meanwhile, Su et al. (2024) also found that as the canopy openness (CO) increases, the LAI decreases, subsequently leading to a higher R/B ratio under the forest canopy7. These studies collectively suggest that the understory light environment is modified by canopy absorption and reflection. However, there is a notable dearth of research on the understory light environment, particularly regarding canopy structure, its influence on the understory light environment, and their combined impacts on understory vegetation.

The understory light environment plays a crucial role in regulating the regeneration, establishment, and productivity-related physiological processes of understory seedlings8. Research has demonstrated that within the morphologically effective radiation (MAR, 350–800 nm) range, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR, 400–700 nm) affects the biomass of understory plants at different developmental stages9,10. Chlorophyll in PSI and PSII light systems absorbs PAR11, primarily focusing on blue light (400–500 nm) and red light (600–700 nm) within this range12, while reflecting more green and far-red light3. Current research primarily focuses on comparing changes in the ratios of red/far-red (R/FR) and R/B light transmitted through the canopy in different coniferous and broad-leaved forests. For example, Leuchner et al. (2007) observed higher variability in the R/FR ratio throughout the growing season in European beech compared to Norway spruce in mature mixed forests9. However, Hertel et al. (2011) emphasized that changes in the R/B ratio have a more significant impact on the growth of these species, especially under sunny conditions, compared to the R/FR ratio3. Therefore, fluctuations in the R/B ratio emerge as a key factor regulating plant growth. Yet, research on the effects of different R/B ratios on the growth of understory saplings remains limited. Hence, gaining a deeper understanding of how different red and blue light environments in the understory influence species performance is vital for quantifying ecosystem dynamics.

Plant functional traits serve as indicators to assess individual performance in the environment. Leaves are the most sensitive and adaptable plant organs in response to spectral changes, adapting to varying light environments by altering key functional traits7. Traits such as specific leaf area (SLA), leaf length, and leaf width reflect a plant’s growth competitiveness, while leaf nitrogen content and chlorophyll content indicate the plant’s photosynthetic capacity13. Primary metabolites signify the plant’s energy supply level, and secondary metabolites represent its defensive ability14. Janse et al. (2007) found that species with stronger shade tolerance exhibit a more significant increase in SLA15. Similarly, Su et al. (2024) discovered that as forest CO increases, the R/B ratio of understory plants rises, while morphological traits (SLA) and photosynthetic traits (total chlorophyll) decrease7. These studies underscore the dynamic nature of plant responses to light environments. In light-competitive environments, plants adopt strategies to regulate morphological traits and chemical defensive traits to balance growth and defense16,17. However, studies assessing the adaptation strategies of understory plants to light quality heterogeneity through a comprehensive range of leaf functional traits (LFT) are relatively scarce. Therefore, examining the response of understory saplings to light environments is crucial for elucidating their growth strategies, competitive dynamics, and the long-term development of forest stands.

In China, the bright coniferous forests of the cold temperate zone are predominantly located in the northeastern region, accounting for 83.86% of the country’s total distribution area18. However, due to historical overexploitation and wildfire disturbances, many regions have degraded into secondary forests dominated by birches19,20. This transformation has reduced the quality of forest structural composition and hindered the natural regeneration of zonal tree species, especially larch. This study focuses on understory larch saplings in the Mohe region. Based on field investigations, relevant indicators related to canopy structure, understory light environment, and functional traits of understory sapling leaves were selected. The objectives of this study are to: (1) investigate the differences in understory light environment characteristics caused by canopy structure; (2) analyze the effects of light quality on the physiological metabolism of understory saplings; and (3) explore the relationship between light quality and plant quota strategies.

Materials and methods

Study site and experimental design

Larch (Larix gmelinii(Rupr.) Kuzen), as the climax community dominant species in boreal-temperate forests, exhibit unique ecological dynamics post-fire. Following wildfire disturbances, birch seeds capitalize on their short-term dormancy breaking characteristics, enabling rapid germination and establishment of high-density seedling communities in burned areas. While these birch-dominated stands can persist for 30–50 years post-disturbance, natural thinning gradually occurs as secondary succession progresses. Larch seedlings, leveraging their cold tolerance and apical dominance, begin colonizing forest gaps, eventually forming age-structured stands that drive community inversion. This process culminates in climax community succession from broadleaf to coniferous dominance through uneven-aged stand development.

The experiment was conducted in two naturally regenerated birch secondary forests (35-year-old) within the Mohe Forestry Bureau, Northeast China (53°0’45.89’’N, 122°27’42.54’’E; average altitude: 313 m). These post-fire (1987) stands feature mountainous brown coniferous forest soil and a cold temperate monsoon climate (average temperature: −2.3 °C; annual precipitation: 724.8 mm). To control site variability, paired plots (total area: 10 km²) were selected with matched slope, aspect, soil moisture, and tree density (2,571 birch stems/ha). The canopy was exclusively birch, with naturally regenerated larch saplings in the understory. Sampling occurred from June 24 to July 3, 2023, coinciding with peak growing season. To delve into the growth of larch saplings, we randomly selected 30 gaps of varying sizes in each plot and designated a representative, robust larch sapling within each gap as the subject of study, recording their geographical locations and topographical features (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we employed the fixed plant survey method to evaluate the regeneration status of larch saplings in the gaps, collecting data on tree height, basal diameter, tree age, 1/2 height diameter, forest gap area, length of the long axis of the forest gap, and width of the long axis of the forest gap (Tab. S1). Simultaneously, to analyze the physiological status of larch saplings, we collected conifer needles from the current year’s branches, combining needles from the same tree into a single sample, resulting in 30 plant samples. The larch needle leaves collected from the wild have been formally identified by Associate Professor Zhonghua Zhang, specializes in botany at Northeast Forestry University.

The collected plant samples were processed into two groups: one group was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C, while another group was used for calculating leaf area through photographic scanning. The remaining samples were first dried in an oven at 105 °C for half an hour, followed by continued drying at 65 °C until constant weight was achieved. After drying, these samples underwent the processes of crushing, grinding, and sieving for more in-depth analysis. Similarly, soil samples were divided into two parts: one part was air-dried for pH measurement, while the other part was sealed in aluminum boxes and brought back to the laboratory for measuring soil moisture content.

Measurement of the light environment index

In the forest gap, a spectrometer and hemispherical imaging technology were used to quantify the prevailing light environment beneath the forest canopy21.

Acquisition of canopy structure indicators

To minimize the impact of direct sunlight on data accuracy, image acquisition was conducted 8:30 − 10:30 am on clear and cloudless days9. A Leica C-LUX digital camera equipped with a fisheye lens was used to capture hemispherical canopy images at the locations of saplings. The images were taken at a height of 1.5 m to avoid interference from shrubs and understory vegetation. The camera was mounted on a leveled monopod and aligned with geographic north. Three photographs were taken for each tree, resulting in a total of 90 images collected22. The images were processed using Gap Light Analyser 2.0 (https://www.caryinstitute.org/science/our-scientists/dr-charles-d-canham/gap-light-analyzer-gla) software, with longitude, latitude, and elevation information input. The zenith angle was set at 60° to obtain canopy structural parameters such as CO and LAI23. Concurrently, understory lighting parameters were derived, including total radiation (Ttot)24.

Measurement of light environment indicators

Measurement of light quality data: Given the local weather, which is predominantly sunny transitioning to cloudy with temperatures ranging from 8 °C to 17 °C, measurements were conducted on a clear and cloudless morning to ensure adequate lighting conditions and minimize the influence of solar altitude angle and cloud cover9,25. PAR was measured at a height of 1.5 m above the canopy of saplings using a Portable Plant Light Analyzer (PLA-30_V2, Hangzhou, China)26. To avoid spatial autocorrelation in the light environment, the distance between gaps should exceed 100 m27,28. The red photon flux RPPF (wavelength range of 600–700 nm, referred to as R) and blue photon flux BPPF (wavelength range of 400–500 nm, referred to as B) were selected to characterize the light quality data in the forest (Tab. S2).

Division of light environment

To understand the impact of the red-to-blue light ratio under forest canopies on seedling growth adaptation, cluster analysis of the red-to-blue light ratios was conducted using the average linkage hierarchical clustering method. Based on this analysis, the under-canopy light environments were classified into three categories: 0.6R:1B, 1.2R:1B, and 1.5R:1B (Fig. 2).

Example of the hemispherical image, spectral feature cluster analysis, and its grouping. (a-c) Unprocessed canopy image; (d-f) canopy image after software analysis and processing. (a, d) is the canopy image under 0.6R: 1B light environment. (b, e) is the canopy image under 1.2R: 1B light environment. (c, f) is the canopy image under 1.5R: 1B light environment. (g) The 3 categories used in cluster analysis: 0.6R:1B is shown in black font, 1.2R:1B is shown in blue font, and 1.5R:1B is shown in red font. (h) Spectral characteristics under forest conditions.

Determination of LFT of leaves of larch

Leaf area measurement: Under identical lighting conditions, larch leaves were mixed. From each light environment, 50 fully expanded, disease-free, mature, and intact conifer needles were selected. A CanScan LIDE400 A4 high-speed photo scanner (Regent Instruments Inc., Tokyo JPN) were used at 4800 × 4800 dpi29,30. Following scanning, ImageJ software (National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) was employed to calculate the leaf area. After scanning, the fresh and dry weights of the leaves were measured, and the leaves were then dried in an oven at 105 °C for half an hour, followed by continued drying at 65 °C until they reached constant weight. The SLA was defined as the ratio of leaf area to dry weight, while leaf dry matter content (LDMC) was defined as the ratio of dry weight to water-saturated fresh weight.

Measurement of chlorophyll content: The light absorption of the needles from 30 larch trees was measured using the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) method. The needles were weighed to an accuracy of 0.05 g, placed into brown test tubes, and 5 mL of DMSO was added. Extraction was conducted in a dark environment at a constant temperature of 60 °C in a water bath for 2 h until the needles lost their color. A blank DMSO solution was used as a control. Each sample was repeated three times. A UV-2100 spectrophotometer (Unico, Dayton, NJ, USA) was used to collect absorbance readings for chlorophyll a (chla), chlorophyll b (chlb), and carotenoids (car) at wavelengths of 665 nm, 649 nm, and 480 nm. The concentrations of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b (mg·g−1) were calculated to determine the chla/b ratio and the total chlorophyll concentration in the extract31,32. Chla, chlb, and carotenoid contents were calculated based on fresh weight using:

Where V denotes the volume of the extract, and m is the fresh weight of the extracted leaves (g).

The contents of soluble sugars, starch, and non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) in larch leaf samples were determined following the method of Yemm and Willis (1954)33. Initially, 0.2 g of leaf powder were subjected to three repeated extractions using 80% ethanol. Anthrone reagent and sulfuric acid oil were added to the extract, heated, cooled, and then the absorbance at 630 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (Mtashsh UV-9000 S, China). The residue after soluble sugar extraction was dried and starch was extracted using 30% perchloric acid, followed by analysis with anthrone reagent34. The non-structural carbohydrate content was obtained by adding the soluble sugar and starch contents.

Extraction of leaf nutrients: Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES) was used to analyze the K, Ca, Na, Mg, Mn, Cu, Fe, and Zn elements in plants. Dried plant tissue samples (0.3 g) were placed in digestion tubes and digested using a microwave digester (MARS, CEM, USA) in a mixture of nitric acid and perchloric acid. After digestion, the contents were transferred to a volumetric flask and diluted to the mark with 2% nitric acid. The carbon (C) concentration in plants was determined using the Walkley-Black method, while the nitrogen (N) concentration was determined using the semi-micro Kjeldahl method35.

Primary metabolite assay: Based on the method of Liu et al.36, metabolites were extracted from leaves using Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)37. See the appendix for details of the process.

Phenolic metabolite analysis. The extraction and determination of phenolic metabolites were based on Liu et al.36. Leaf metabolites were extracted by Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS)37. See the appendix for details on this process.

Determination of key enzyme activities of metabolic pathways: Enzyme activities in plant samples including sucrose synthase (SS), sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS), sucrose invertase (INV), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), citrate synthase (CS) and L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). See the appendix for details of this process (Tab. S3).

Statistical analysis

All of the data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) and were compared using SPSS (SPSS 24.0, SPSS, Inc., USA). GC-MS raw data were converted to NetCDF files by data analysis software (Agilent GC-MS 5975). The compounds were identified by structural comparison and compared with the retention times and mass spectra of known compounds in the NIST library. LC-MS data were analysed and normalized by the mass spectrometry software MassLynxTM (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). We used Metaboanalyst 5.0 for statistical partial least squares analysis (PLS-DA), orthogonal partial least squares analysis (OPLS-DA), multivariate variation, and T tests, as well as for path enrichment analysis. SPSS 19.0 was also used for Pearson correlation analysis (p < 0.05), and Cytoscape version 3.7.1 was used to visualize network correlations38. Fan diagrams, ring chart and Venn diagrams were also generated using Origin 2017. Histograms and volcano plots were generated using GraphPad Prism 8. Bubble charts were generated in Python 3.10. Principal component analysis, heatmaps, GO plots, and bubble plots were further generated with the R-4.2.1 packages factoextra17, ggrepel (https://github.com/slowkow/ggrepel), pheatmap (https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/pheatmap/versions/1.0.12), circulalize39, and ggplot2 (https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2).

Results

Canopy structure and understorey light environment

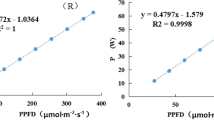

To assess the relationship between canopy structure, light transmittance, and the under-canopy light environment, we conducted a linear regression analysis (Fig. 3). The results indicate that CO positively correlates with under-canopy red light proportion, while LAI negatively correlates. Transmitted total solar radiation positively correlates with the R/B ratio. Maximum red light proportion occurs with high CO and low LAI, aiding in interpreting the R/B ratio’s effects on larch sapling photosynthesis.

Morphological characteristics

A study was conducted on the growth effects of larch saplings under different light conditions. The results indicated that under the light environment of 0.6R:1B, the leaf width significantly increased by 16.67% compared to 1.5R:1B, while the change in leaf length was not apparent. Furthermore, the SLA was the highest under 0.6R:1B, with an increase of 24.78% compared to 1.5R:1B. However, the LDMC of leaves was the lowest under 0.6R:1B, decreasing by 10.53% compared to 1.5R:1B (Fig. 4).

Changes in leaf physiological characteristics

The photosynthetic traits of larch saplings vary significantly under different light environments. As the proportion of red light increases, the contents of Chla, Chlb, Car, and Chl total also increase accordingly. Compared to the light environment with a ratio of 0.6R:1B, the contents of Chla, Chlb, Car, and Chl total increase by 18.67%, 22.22%, 17.39%, and 17.48%, respectively, under the light environment with a ratio of 1.5R:1B. There is no significant difference in the Chla/b ratio across different light environments (Table 1).

Changes in leaf physiological characteristics

Compared to the light environment of 0.6R:1B, the starch content of larch significantly increased by 2.39% (p < 0.05) under 1.5R:1B. Concurrently, the contents of soluble sugars and NSCs also showed increases, by 3.52% and 3.24%, respectively. However, these increases were not statistically significant (Fig. S1).

We evaluated the impact of different light environments on photosynthesis-related nutrient characteristics in larch using ANOVA (p < 0.05). The results indicated that only 5 elements exhibited significant differences across different lighting environments (Tab. S4). Among them, C dominated with a proportion not less than 40%, while the contents of other elements were relatively low, accounting for less than 2% each. Further comparisons revealed that, compared to the 0.6R:1B light environment, the contents of C and K per unit leaf area of larch significantly increased in the 1.5R:1B light environment, with carbon content showing the most pronounced increase, rising from 49 to 62%. Conversely, under the 1.5R:1B light environment, the contents of Ca, Mg, and Mn per unit leaf area decreased significantly. Notably, although the N content per unit leaf area did not show significant differences across different light environments, it exhibited a decreasing trend as the proportion of red light increased (Fig. 5).

Histograms of the percentage of larch grown under different light environments per unit leaf area (n = 3). (a) C content per unit leaf area (%); (b) K content per unit leaf area (%); (c) Ca content per unit leaf area (%); (d) Mg content per unit leaf area (%); (d) Mn content per unit leaf area (%); (f) N content per unit leaf area (%). *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001.

To conduct an in-depth analysis of metabolite synthesis and catabolism in different light environments, we measured the activities of key enzymes involved in sugar metabolism, carbon assimilation, and defense metabolic processes. Specifically, under 1.5R:1B, the activities of SPS, SS, and PAL in larch leaves were upregulated by 118%, 45%, and 60%, respectively, while the activities of CS and INV were downregulated by 10% and 86%, respectively. Although PEPC did not show a significant difference under 1.5R:1B, its activity was still upregulated by 4% (Fig. 6).

Differential distribution of key enzyme activities in larch leaf metabolites between different light environments (n = 3). (a) sucrose synthase (SS); (b) sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS); (c) sucrose invertase (INV); (d) phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC); (d) citrate synthase (CS); (f) L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL). *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001.

Changes in primary metabolites

A total of 80 metabolites were detected and categorized into 7 groups (Fig. S2a,): 22 sugars, 19 organic acids, 13 amino acids, 11 alcohols, 4 amines, 6 sugar alcohols, and 5 other compounds (Fig. 7a). PLS-DA plots showed that PC1 and PC2 contributed to 44.5% and 27.9% of the total variation, respectively, effectively discriminating larch components in different light environments (Fig. 7b). Loading plots provided further insights into the specific metabolites that differentiate larch components in different light environments, included tartaric acid, fumaric acid, sucrose, maltose, galactopyranose, and various amino acids and sugar alcohols (Fig. S2b).

To investigate metabolic changes in larch under varying light conditions, we used the OPLS-DA model to analyze metabolites (Fig. S2c-e). The results are visually illustrated using volcano plots and Venn diagrams with criteria of ploidy change scores ≥ 1 or ≤ −1 and VIP values ≥ 1. There were 43 significantly different metabolites between 1.2R:1B and 0.6R:1B (24 upregulated and 19 downregulated) (Fig. S2f), 42 between 1.5R:1B and 0.6R:1B (22 upregulated and 20 downregulated) (Fig. S2 g), and 35 between 1.5R:1B and 1.2R:1B (17 upregulated and 18 downregulated) (Fig. S2 h). A total of 59 common differentially abundant metabolites were identified in the three control groups (Fig. 7c). Further analysis revealed that these differentially abundant metabolites were mostly composed of sugars and amino acids, accounting for 25.4% and 22%, respectively, of the total differentially abundant metabolites (Fig. 7d). Therefore, sugars and amino acid compounds are considered representative metabolites of larch in different light environments.

The primary differentially abundant metabolites of larch leaves under different light conditions were compared in pairs (n = 3). (a) Classification of 80 primary metabolites. (b) PLS-DA score plots; (c) Venn diagram shows the rich metabolites that are shared or unique and different; (d) Ring chart shows the classification of unique differential metabolites. With different coloured points and shapes representing different sample groups.

Changes in secondary metabolites

Utilizing targeted metabolomics technology, 29 metabolites were identified via the LC-MS platform. Cluster heatmaps analyzed differential metabolite accumulation under various light conditions, revealing higher C6 C3 C6-type metabolite accumulation under 1.5R:1B than 0.6R:1B (Fig. 8a). The PCA further explored phenolic metabolite variations, with PC1 accounting for 49.2% of total variance influenced by syringic acid, sinapic acid, chrysin, taxifolin, hesperetin, and isoliquiritigenin. PC2 explained 16.4% of total variance, primarily involving p-hydroxycinnamic acid, genistin, and naringenin (Fig. 8b).

Second, by using PCA, we further observed the differences in metabolites between different groups and performed fold change (log2 (FC)) and t-test (FDR < 0.05) analyses on the data. In the comparison of 1.2R:1B vs. 0.6R:1B, PC1 explained 41.3% of the total variation, with significant increases in hesperetin, naringin, quercitrin, and benzoic acid. Conversely, p-hydroxycinnamic acid, catechin acid, and glycyrrhizin decreased significantly (Tab. S5). The PC2 accounted for 25.3% of the total variation, and the main metabolites contributing to the variation were genistein, apigenin, galanin, and cinnamic acid (Fig. 8c, f). For 1.5R:1B vs. 0.6R:1B, PC1 accounted for 60.2% of the total variation, with increased expression of multiple metabolites including daidzein, hesperetin, and quercitrin, while isoliquiritigenin decreased (Tab. S5). PC2 explained 20.3% of the total variation in this comparison, with rutin, genistein, and caffeic acid as key contributors (Fig. 8d, g). In the comparison of 1.5R:1B vs. 1.2R:1B, PC1 explained 63.1% of total variation, with increases in taxifolin, hesperetin, and others, while benzoic acid, protocatechin, and isoliquiritigenin decreased (Tab. S5). PC2 accounted for 17.5% of variation, with naringenin, vanillic acid, and others as main contributors (Fig. 8e, h).

Heatmap visualization, Principal component analysis, and fold change in phenolic metabolites in larch leaves under different lighting conditions (n = 3). (a) Heatmap analysis of target phenolic metabolites; (b) PCA of target phenolic metabolites; (c-e) PCA of phenolic metabolites between different comparison groups; (f-h) FC of phenolic metabolites between different comparison groups. Orange represents the C6 C1 compound, purple represents the C6 C3 compound, and blue represents the C6 C3 C6 compound. Red indicates a high concentration of compounds; other colours indicate a low concentration (colour key scale above the heatmap); b: Red arrows and fonts represent major contributions to PC1, and blue arrows and fonts represent major contributions to PC2.

Analysis of network correlations between elements and metabolites

Through Pearson correlation analysis, the correlation between various metabolites and elements was established (coefficient > 0.6, p < 0.05) were constructed. This network comprises 79 nodes, with a total of 1,126 correlations identified, including 598 positive correlations and 528 negative correlations. Notably, organic acids, sugars, and amino acids dominate this network, with the largest metabolite group consisting of sugar metabolites (Fig. 9a). To identify key nodes within the network, we used the CytoHubba tool. By applying the MCC algorithm to calculate the core targets within the network, we further selected the top 10 core nodes (Fig. 9b). In this correlation network, sugar and sugar alcohol metabolites play a pivotal role, forming extensive connections with other metabolites and elements in the network, thereby exerting significant influence on the regulation and stability of the overall metabolic process.

Association networks of metabolites and nutrients in larch leaves under different light conditions. (a) Correlation row network diagram, (b) MCC calculation score diagram. Nodes represent metabolites and elements, and edges represent correlations between them. Metabolites of the same class are shown in the same colour. Red lines indicate positive correlations, and blue lines indicate negative correlations. The node size reflects the number of edge line connections, and the edge line thickness reflects the strength of the correlation.

Pathway enrichment analysis and metabolic pathway of the photoinduced response

To further investigate the changes in metabolic processes under different light environments, we constructed a metabolic network model, primarily encompassing significantly differentiated metabolites, regulatory elements, and key enzymes within metabolic pathways. Our study revealed distinct dynamic variations in sugar metabolism, amino acid metabolism, the TCA cycle, and phenolic metabolism under varying light conditions (Fig. 10). Specifically, we observed upregulation of key products involved in sugar synthesis and metabolism, such as sucrose, lactose, galactopyranose, sedoheptulose and D-erythrose. Concurrently, during the conversion of phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate and phenylalanine, there was a marked increase in l-phenylalanine content, and acetyl-CoA was effectively channeled into the TCA cycle. In the 0.6R:1B environment, metabolites participating in the TCA cycle, including fumaric acid and succinic acid, exhibited an increasing trend. Additionally, the efficiency of l-proline synthesis via the α-ketoglutarate pathway mediated by glutamate declined, while l-glutamine levels rose. Under 1.5R:1B conditions, most amino acids and phenolic metabolites, including C6 C3 C6-structured compounds like chrysin, hesperetin, quercitrin, and taxifolin, showed significant accumulation. From a metabolic pathway perspective, the 0.6R:1B environment primarily promoted organic acid metabolism pathways, while the 1.5R:1B environment predominantly activated sugar metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and phenolic metabolism pathways.

Comparison of changes in leaf metabolites in larch plants under different light conditions. The change in differentially metabolites is expressed as the ratio of log2 (FC). Blue indicates a decrease, and orange indicates an increase. The dashed and solid lines indicate indirect and direct connections, respectively. Arrows indicate the direction of the transformation. The three consecutive boxes represent the ratios of 1.2R:1B vs. 0.6R:1B, 1.5R:1B vs. 0.6R:1B, 1.5R:1B vs. 1.2R:1B. The red box represents an increase, and the blue box represents a decrease. The three rectangular boxes next to the arrow represent the FC ratio of metabolites, the rectangle next to the enzyme activity represents the FC ratio of enzyme activity, and the number inside represents the multiple of increase or decrease.

Discussion

Effect of canopy structure on the light environment

Canopy structure is a crucial component of forest ecosystems, influencing resource allocation and the internal light environment40, and subsequently affecting the regeneration and ecological functions of understory plants41. Previous studies have investigated effective methods for assessing the understory light environment4,42. In this study, factors related to canopy structure exhibited significant correlations with the understory light environment, with CO and LAI having notable effects on radiation intensity and spectral composition (Fig. 3). Therefore, measuring CO and LAI can effectively estimate light conditions within the stand. Additionally, combining radiation intensity and spectral composition in the understory layer can be used to analyze and assess the light environment within the stand43. The study shows that greater CO leads to higher light transmittance22. Changes in light transmittance affect the spectral composition under the canopy, where radiation in the blue light region is typically lower, while radiation in the red and far-red regions increases43. These changes in the R/B ratio were first noted by Woodward (1983), who increases an exponential decrease in blue light for Buddleia davidii in shaded areas44. However, some studies have also indicated that the R/B ratio described in beeches and spruces under high canopy density (full foliage period)6. In this study, the proportion of red light increased with CO, while the R/B ratio decreased with increasing canopy density. This may be due to the presence of leaf wax on the surface of birch leaves, which acts as a reflective surface to scatter excess incident radiation when light passes through the canopy45.

Effects of the understorey light environment on the LFT of sapling

LFT represent the basic responses of plants to changes in light environments and can be used to predict growth46. Among them, SLA reflects the ability of plant leaves to intercept light and self-protect, and is closely related to the growth-survival trade-off of plants16,47. In this study, under conditions of low CO, the SLA of larch saplings increased, resulting in an enhanced light interception per unit leaf biomass (Fig. 4c). The chlorophyll a/b ratio reflects the proportion of Photosystem II (PSII) to PSI48,49. A constant ratio may suggest that larch prioritizes maintaining the balance between photosystems during light quality adaptation, thereby avoiding photoinhibition. The cha/b ratio remains constant within the R/B ratio, but carotenoid content and specific leaf area increase50. Larch compensates for changes in chlorophyll composition by increasing specific leaf area or adjusting carotenoid levels. In this study, we found that the LFT of larch seedlings vary with changes in the R/B ratio. Specifically, under a red-to-blue light ratio of 1.5R:1B, they tend to exhibit an energy distribution pattern with higher leaf carbon content. In contrast, under a red-to-blue light ratio of 0.6R:1B, they enhance their defense capabilities and nutrient storage abilities by increasing SLA and the contents of Ca and Mg. Therefore, during the early growth of larch, adjustments in its leaf functional traits are not only a response to changes in the light environment but also an important manifestation of its adaptation to different growth conditions and the achievement of optimal growth strategies.

Primary-secondary metabolism allocation in different light environments: consideration of resource acquisition strategies

Plants have developed strategies to cope with environmental changes by balancing the coordination of multiple functional traits51. Resource-acquisition plants achieve rapid growth by increasing SLA and leaf nitrogen content52. In contrast, resource-conservation plants grow slowly with high LMDC, low SLA, and low N content53. Additionally, plants can adapt to various environmental changes by altering nutritional traits37,54, metabolic traits55, and defensive traits56,57. Previous studies have reported the impact of CO on energy metabolism. Specifically, Li et al. (2020) observed that under shading conditions, sugar content decreased and energy demand reduced in plants55. In our research also observed similar adaptive trade-off patterns, which are closely related to the light environment. Specifically, under 1.5R:1B light, SLA decreased, while LMDC, C, and K increased. Maltose decreased, ribitol, and d-glucitol increased, fumaric acid decreased, and SS and SPS activities enhanced. In addition, under the 1.5R:1B condition, the increased activities of SPS and SS (Fig. 6) promote sucrose synthesis, potentially diverting nitrogen resources towards carbon metabolism.

Amino acids are crucial for growth and development, providing energy and nitrogen, and serving as the starting substrate for flavonoid metabolism58. Recent studies show that light deficiency reduces amino acid content in trees59, with blue light inhibiting nitrogen-containing compound accumulation60. In our study, we found that a low red-to-blue light ratio decreased l-aspartic acid content, possibly aiding in stress protein production or repair in a closed understorey environment61, while succinic and fumaric acids accumulated due to decreased citric acid levels and increased citric acid lyase activity. Additionally, light promotes phenylalanine metabolism for flavonoid synthesis by upregulating the phenylalanine ammonia reaction62,63. In particular, blue light not only affects the synthesis of flavonoids, even if this modulation (positive or negative) depends on the plant species, but also affects the light intensity64. Previous studies have reported that light deficiency significantly affects the total flavonoid, kaempferol, quercetin, and isorhamnetin contents in plant leaves65. Under the 1.5R:1B condition, the accumulation of flavonoids (such as hesperetin and taxifolin) may enhance antioxidant capacity (Fig. 8a). Similarly, Wang et al. (2020) found that tea plants enhance stress resistance through the upregulation of flavonoids under high light intensity66. Although there was no significant change in total nitrogen content (Fig. 5f), the accumulation of glutamine (Fig. 7d) and increased PAL activity (Fig. 6f) suggest that nitrogen may be preferentially allocated to phenylalanine metabolism to support flavonoid synthesis rather than to photosynthetic proteins such as Rubisco under the 1.5R:1B condition. This ‘defense-for-growth trade-off’ strategy aligns with the light-regulated defense pathway proposed by Ballaré (2014)67. Therefore, the trade-off between resource acquisition and defense in larch shown in this study indicates that under the 0.6R:1B condition, the high SLA and low LDMC (Fig. 4c) conform to the ‘rapid resource acquisition’ strategy in the leaf economics spectrum53, potentially facilitating rapid leaf area expansion in shaded environments. Conversely, the high LDMC, high carbon storage, and defensive metabolism under the 1.5R:1B condition point to a ‘conservative’ strategy, enhancing its persistent competitiveness in gap environments.

Conclusion

In summary, canopy structure exerts varying effects on the lighting environment of forest stands, subsequently causing significant changes in the resource allocation patterns of larch saplings. Under conditions of low CO and a low proportion of red light, larch saplings adopt “acquisition” strategy, enhancing carbon source utilization efficiency by increasing the activity of enzymes that regulate SLA. Conversely, under conditions of high CO and a high proportion of red light, they switch to a “conservative” strategy, prioritizing carbon storage and defense. These results indicate that larch can flexibly adjust its physiological and metabolic processes in response to changes in lighting conditions to adapt to different light environments. This light adaptation strategy not only aids the survival and growth of larch under complex lighting conditions but also provides a new perspective for understanding the physiological mechanisms of plant light adaptation processes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LFT:

-

Leaf functional traits

- CO:

-

Canopy openness

- LAI:

-

Leaf area index

- SS:

-

Sucrose synthase

- SPS:

-

Sucrose-phosphate synthase

- INV:

-

Sucrose invertase

- PEPC:

-

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- PAL:

-

L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase

- CS:

-

Citrate synthase

- chla:

-

Chlorophyll a

- chlb:

-

Chlorophyll b

- car:

-

Carotenoids

- chla/b:

-

chlorophylla/chlorophyllb

- R/FR:

-

Red/far-red

- R/B:

-

Red/ Bule ratio

- 0.6R:1B:

-

Red:bule=0.6:1

- 1.2R:1B:

-

Red:bule=1.2:1

- 1.5R:1B:

-

Red:bule=1.5:1

- TCA cycle:

-

tricarboxylic acid cycle

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- FC:

-

Fold change

- SLA:

-

Specific leaf area

- NSCs:

-

non-structural carbohydrates

- LDMC:

-

leaf dry matter content

- Ttot:

-

Total radiation

- K:

-

Potassium

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- Na:

-

Sodium

- Mg:

-

Magnesium

- Mn:

-

Manganese

- Cu:

-

Copper

- Fe:

-

Iron

- Zn:

-

Zinc

- C:

-

Carbon

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- UPLC-MS:

-

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- GC-MS:

-

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- PLS-DA:

-

partial least squares analysis

- OPLS-DA:

-

orthogonal partial least squares analysis

- LDMC:

-

Leaf dry matter content

- NSC:

-

non-structural carbohydrates

- VIP:

-

variable importance in projection

- Larch:

-

Larix gmelinii (Rupr.) Kuzen

References

Gendreau-Berthiaume, B. (ed Kneeshaw, D.) Influence of gap size and position within gaps on light levels. Int. J. Forestry Res. 2009 581412 https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/581412 (2009).

Zhang, T., Yan, Q. L., Wang, J. & Zhu, J. J. Restoring temperate secondary forests by promoting sprout regeneration: effects of gap size and within-gap position on the photosynthesis and growth of stump sprouts with contrasting shade tolerance. For. Ecol. Manag. 429, 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.07.025 (2018).

Hertel, C., Leuchner, M. & Menzel, A. Vertical variability of spectral ratios in a mature mixed forest stand. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151, 1096–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.03.013 (2011).

Navrátil, M., Špunda, V., Marková, I. & Janouš, D. Spectral composition of photosynthetically active radiation penetrating into a Norway Spruce canopy: the opposite dynamics of the Blue/red spectral ratio during clear and overcast days. Trees 21, 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-007-0124-4 (2007).

Wei, H. X., Chen, X., Chen, G. S. & Zhao, H. T. Foliar nutrient and carbohydrate in Aralia elata can be modified by understory light quality in forests with different structures at Northeast China. Ann. Res. 62, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.15287/afr.2019.1395 (2019).

Hertel, C., Leuchner, M., Rötzer, T. & Menzel, A. Assessing stand structure of Beech and Spruce from measured spectral radiation properties and modeled leaf biomass parameters. Agric. For. Meteorol. 165, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.06.008 (2012).

Su, S. C., Jin, N. Q. & Wei, X. L. Effects of thinning on the understory light environment of different stands and the photosynthetic performance and growth of the reforestation species Phoebe Bournei. J. Forestry Res. 35 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-023-01651-0 (2024).

Endler, J. A. The color of light in forests and its implications. Ecol. Monogr. 63, 2–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937121 (1993).

Leuchner, M., Menzel, A. & Werner, H. Quantifying the relationship between light quality and light availability at different phenological stages within a mature mixed forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 142, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.10.014 (2007).

Combes, D., Sinoquet, H. & Varlet-Grancher, C. Preliminary measurement and simulation of the Spatial distribution of the morphogenetically active radiation (MAR) within an isolated tree canopy. Ann. For. Sci. 57, 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest:2000137 (2000).

Grant, R. H. Partitioning of biologically active radiation in plant canopies. Int. J. Biometeorol. 40, 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02439408 (1997).

Smith, H. Sensing the light environment: the functions of the phytochrome family. In Photomorphogenesis in Plants (eds Kendrick, R. E. & Kronenberg, G. H. M.) 377–416 (Springer Netherlands, 1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1884-2_15.

Han, T. T. et al. Dominant ecological processes and plant functional strategies change during the succession of a subtropical forest. Ecol. Indic. 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.109885 (2023).

Tyagi, J. & Kumar, M. Plant functional trait: concept and significance. In Plant Functional Traits for Improving Productivity (eds Kumar, N. & Singh, H.) 1–22 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1510-7_1.

Janse Ten Klooster, S. H., Thomas, E. J. P. & Sterck, F. J. Explaining interspecific differences in sapling growth and shade tolerance in temperate forests. J. Ecol. 95, 1250–1260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01299.x (2007).

Cerrudo, I. et al. Exploring growth-defence trade-offs in arabidopsis: phytochrome B inactivation requires JAZ10 to suppress plant immunity but not to trigger shade-avoidance responses. Plant. Cell. Environ. 40 (5), 635–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12877 (2017).

Wasternack, C. A plant’s balance of growth and defense - revisited. New. Phytol. 215, 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14720 (2017).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on earth, BioScience, 51 933–938. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2

Luo, X. et al. Spatial simulation of the effect of fire and harvest on aboveground tree biomass in boreal forests of Northeast China. Landsc. Ecol. 29, 1187–1200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-014-0051-x (2014).

Xu, W. R., He, H. S., Hawbaker, T. J., Zhu, Z. L. & Henne, P. D. Estimating burn severity and carbon emissions from a historic Megafire in boreal forests of China. Sci. Total Environ. 716, 136534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136534 (2020).

Inoue, A., Yamamoto, K., Mizoue, N. & Kawahara, Y. Effects of image quality, size and camera type on forest light environment estimates using digital hemispherical photography. Agric. For. Meteorol. 126, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2004.06.002 (2004).

Beaudet, M. & Messier, C. Variation in canopy openness and light transmission following selection cutting in Northern hardwood stands: an assessment based on hemispherical photographs. Agric. For. Meteorol. 110, 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(01)00289-1 (2002).

Arietta, A. Z. A. Estimation of forest canopy structure and understory light using spherical panorama images from smartphone photography. Forestry: Int. J. For. Res. 95, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpab034 (2021).

Jukes, M. R., Ferris, R. & Peace, A. J. The influence of stand structure and composition on diversity of canopy Coleoptera in coniferous plantations in Britain. For. Ecol. Manag. 163, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00536-9 (2002).

De Pauw, K. et al. De Frenne, forest understorey communities respond strongly to light in interaction with forest structure, but not to microclimate warming. New. Phytol. 233, 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17803 (2022).

Chao, K. J. et al. Understorey light environment impacts on seedling establishment and growth in a typhoon-disturbed tropical forest. Plant Ecol. 223, 1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-022-01255-4 (2022).

Tsai, H. C., Chiang, J. M., McEwan, R. W. & Lin, T. C. Decadal effects of thinning on understory light environments and plant community structure in a subtropical forest. Ecosphere 9, e02464. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2464 (2018).

Lin, T. C. et al. Influence of typhoon disturbances on the understory light regime and stand dynamics of a subtropical rain forest in Northeastern Taiwan. J. For. Res. 8, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-002-0019-6 (2003).

Fellner, H., Dirnberger, G. F. & Sterba, H. Specific leaf area of European larch (Larix decidua M ill). Trees 30, 1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-016-1361-1 (2016).

Williams, A. G. & Nelson Spatial variation in specific leaf area and horizontal distribution of leaf area in juvenile Western larch (Larix occidentalis Nutt). Trees 32, 1621–1631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-018-1738-4 (2018).

Wang, W. et al. Methodological comparison of chlorophyll and carotenoids contents of plant species measured by DMSO and acetone-extraction methods. Bull. Bot. Res. 29, 224. https://doi.org/10.7525/j.issn.1673-5102.2009.02.017 (2009).

Jin, L. et al. Photosynthetic acclimation of larch to the coupled effects of light intensity and water deficit in regions with changing water availability. Plants 13, 1891. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13141891 (2024).

Yemm, E. W. & Willis, A. J. The Estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J. 57 (3), 508–514. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj0570508 (1954).

Qin, X., Li, F., Chen, X. & Xie, Y. Growth responses and non-structural carbohydrates in three wetland macrophyte species following submergence and de-submergence. Acta Physiol. Plant. 35, 2069–2074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-013-1241-x (2013).

Song, X. Q. et al. Study on the effects of salt tolerance type, soil salinity and soil characteristics on the element composition of Chenopodiaceae halophytes. Plants-Basel 11, 1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11101288 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. The integration of GC–MS and LC–MS to assay the metabolomics profiling in Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius reveals a tissue- and species-specific connectivity of primary metabolites and ginsenosides accumulation. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 135, 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2016.12.026 (2017).

Song, X. Q. et al. Suaeda glauca and Suaeda Salsa employ different adaptive strategies to Cope with saline-alkali environments. Agronomy-Basel 12, 2496. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12102496 (2022).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Gu, Z., Gu, L., Eils, R., Schlesner, M. & Brors, B. Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30, 2811–2812. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu393 (2014).

Yamada, T., Yoshioka, A., Hashim, M., Liang, N. & Okuda, T. Spatial and Temporal variations in the light environment in a primary and selectively logged forest long after logging in Peninsular Malaysia. Trees-Struct Funct. 28, 1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-014-1040-z (2014).

Lhotka, J. M., Cunningham, R. A. & Stringer, J. W. Effect of silvicultural gap size on 51 year species recruitment, growth and volume yields in Quercus dominated stands of the Northern Cumberland plateau, USA, Forestry, 91 451–458. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpy003

Lochhead, K. D. & Comeau, P. G. Relationships between forest structure, understorey light and regeneration in complex Douglas-fir dominated stands in south-eastern British Columbia. For. Ecol. Manag. 284, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.07.029 (2012).

Orman, O., Wrzesiński, P., Dobrowolska, D. & Szewczyk, J. Regeneration growth and crown architecture of European Beech and silver Fir depend on gap characteristics and light gradient in the mixed montane old-growth stands. For. Ecol. Manag. 482, 118866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118866 (2021).

Woodward, F. I. Instruments for the measurement of photosynthetically active radiation and red, far-red and blue light. J. Appl. Ecol. 20, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.2307/2403379 (1983).

Gordon, D. C., Percy, K. E. & Riding, R. T. Effects of UV-B radiation on epicuticular wax production and chemical composition of four Picea species. New. Phytol. 138, 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00116.x (1998).

dos Santos, V. A. H. F. & Ferreira, M. J. Are photosynthetic leaf traits related to the first-year growth of tropical tree seedlings? A light-induced plasticity test in a secondary forest enrichment planting. For. Ecol. Manag. 460, 117900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.117900 (2020).

Dahlgren, C. P. et al. Marine nurseries and effective juvenile habitats: concepts and applications. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 312, 291–295. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps312291 (2006).

Lei, T., Tabuchi, R., Kitao, M. & Koike, T. Functional relationship between chlorophyll content and leaf reflectance, and light-capturing efficiency of Japanese forest species. Physiol. Plant. 96, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00452.x (2006).

Terashima, I., Hanba, Y. T., Tazoe, Y., Vyas, P. & Yano, S. Irradiance and phenotype: comparative eco-development of sun and shade leaves in relation to photosynthetic CO2 diffusion. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erj014 (2005).

Long, W. X., Zang, R. G., Schamp, B. S. & Ding, Y. Within- and among-species variation in specific leaf area drive community assembly in a tropical cloud forest. Oecologia 167, 1103–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-011-2050-9 (2011).

Díaz, S. et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 529, 167–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16489 (2016).

Li, J. L. et al. A whole-plant economics spectrum including bark functional traits for 59 subtropical Woody plant species. J. Ecol. 110, 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13800 (2022).

Wright, I. J. et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428, 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02403 (2004).

Rouached, H. & Tran, L. S. P. Regulation of plant mineral nutrition: transport, sensing and signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 29717–29719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161226198 (2015).

Li, Y. C. et al. Metabolic regulation profiling of carbon and nitrogen in tea plants [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] in response to shading. J. Agr Food Chem. 68, 961–974. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05858 (2020).

Chauvin, K. M. et al. Decoupled dimensions of leaf economic and anti-herbivore defense strategies in a tropical canopy tree community. Oecologia 186, 765–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-4043-9 (2018).

de Tombeur, F. et al. A shift from phenol to silica-based leaf defences during long-term soil and ecosystem development. Ecol. Lett. 24, 984–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13713 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Methyl salicylate enhances flavonoid biosynthesis in tea leaves by stimulating the phenylpropanoid pathway. Molecules 24, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24020362 (2019).

Zhang, Q. F., Liu, M. Y. & Ruan, J. Y. Integrated transcriptome and metabolic analyses reveals novel insights into free amino acid metabolism in Huangjinya tea cultivar. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00291 (2017).

Formisano, L. et al. Between light and shading: morphological, biochemical, and metabolomics insights into the influence of blue photoselective shading on vegetable seedlings. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 890830. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.890830 (2022).

Han, M. et al. L-Aspartate: an essential metabolite for plant growth and stress acclimation. Molecules 26, 1887. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26071887 (2021).

Seo, J. M., Arasu, M. V., Kim, Y. B., Park, S. U. & Kim, S. J. Phenylalanine and LED lights enhance phenolic compound production in Tartary buckwheat sprouts. Food Chem. 177, 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.12.094 (2015).

Liu, Y., Fang, S. Z., Yang, W. X., Shang, X. L. & Fu, X. X. Light quality affects flavonoid production and related gene expression in Cyclocarya paliurus. J. Photoch Photobio B. 179, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.01.002 (2018).

Wang, P. J. et al. Exploration of the effects of different blue LED light intensities on flavonoid and lipid metabolism in tea plants via transcriptomics and metabolomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134606 (2020).

Deng, B. et al. Integrated effects of light intensity and fertilization on growth and flavonoid accumulation in Cyclocarya paliurus. J. Agr Food Chem. 60, 6286–6292. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf301525s (2012).

Wang, P. J. et al. Exploration of the effects of different blue LED light intensities on flavonoid and lipid metabolism in tea plants via transcriptomics and metabolomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 29, 4606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134606 (2020).

BallaréC.L. Light regulation of plant defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 335–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040145 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2022YFF1300502-03), Special Foundation for National Science and Technology Basic Research Program of China (grant number 2019 FY100505), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 41730641).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaoqian Song: Investigation, Writing-Original draft preparation, Paper revision. Zhonghua Zhang: Investigation. Haiyan Huang: Collected the data. Xin Guan: Involvement methodology. Lu Jin: Involvement methodology. Yu Shi: Involvement methodology. Wenjie Wang: Manuscript revision, Validation. Zhonghua Tang: Experimental design, Visualization, Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Methodology.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. We confirm that all experimental studies and field surveys, including those involving cultivated and wild plants, were conducted by relevant guidelines, regulations, and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, X., Zhang, Z., Huang, H. et al. Leaf functional metabolic traits reveal the adaptation strategies of larch trees along the R/B ratio gradient at the stand level. Sci Rep 15, 19185 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04113-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04113-1