Abstract

20-30% of newly diagnosed Acute myeloid leukemia(AML) patients fail to achieve complete response (CR) following intensive induction chemotherapy. This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of reinduction regimens in improving CR rates among newly diagnosed AML patients who did not achieve partial response(PR) after initial intensive induction therapy. We conducted a retrospective analysis of 175 newly diagnosed AML patients aged 18–60 years, treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University between January 2020 and March 2024. Patients who did not achieve PR after first line inductive therapy were switched to alternative intensive chemotherapy regimens or regimens including venetoclax and azacitidine. After the first induction cycle, the overall response rate(ORR) was 82.8%. For patients with no response, early replacement of reinduction regimens, especially those containing venetoclax, led to an ORR of 90.2% after two cycles of induction therapy. We recommend that young patients with newly diagnosed AML be primarily treated with DA/IA induction therapy. For those who fail to achieve remission, early replacement of re-induction therapy enhances the therapeutic efficacy of newly diagnosed young adult AML.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past 50 years, daunorubicin and cytarabine regimen (DA regimen, also known as 3 + 7 regimen) has become the standard induction therapy for adult Acute myeloid leukemia(AML), especially for young and fit patients1,2. After dose exploration, daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 and cytarabine 100–200 mg/m2 are the most widely used induction therapy regimen3,4,5. The complete response (CR) rate of this regimen is 60–80% in younger patients and 45–60% in older patients (age ≥ 60 years)6. Daunorubicin can be replaced with idarubicin (IA), which achieves the same efficacy as the DA regimen7. DA regimen combined with other drugs can improve the CR rate and overall survival8,9. Venetoclax is a well-known BCL2 inhibitor, which plays a pivotal role in the apoptosis pathway of AML. In older and unfit patients, patients treated with venetoclax combined with demethylation drugs or low dose cytarabin had a longer overall survival (OS) and a higher response rate10,11,12,13,14. Venetoclax combined with azacitidine has become a frontline therapy for elderly and unfit patients. In younger patients (age < 60 years), two previous clinical trials using venetoclax combined with daunorubicin and cytarabine (3 + 7 regimen and 2 + 6 regimen) as induced therapy achieved an composite CR rate of more than 90%9,15. However, intensive chemotherapy combined with venetoclax increases hematologic and non-hematologic adverse effects, which limits its widespread application11,16.

When a patient does not achieve CR after receiving at least two cycles of intense induction therapy, the patient is deemed resistant, with limited options for treatment and a dismal outlook. Therefore, selecting a re-induction regimen following the first treatment for patients who are not in CR is crucial. The 2022 ELN guidelines recommend reinduction of the 3 + 7 regimen again or replacement with a regimen containing higher doses of cytarabine17. But previous study has shown that the CR rate of cytarabin-based re-induction regimen is 56.3%, which is independent of cytarabine dose18.

To increase the ORR and reduce the adverse effects of induction therapy, we performed a retrospective analysis to assess the safety and effectiveness of patients who had early replacement of an intense chemotherapy regimen or a treatment that includes azacitidine and venetoclax after failing DA or IA induction therapy.

Result

Patient characteristics

The basic characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. From January 1, 2020 to May 31, 2024, a total of 175 patients were included in our retrospective study, with a median follow-up of 15 months (IQR 7–29). A total of seven patients were lost to follow-up in this study. During consolidation therapy, three patients discontinued treatment and could not be contacted by any means. Additionally, four patients completed consolidation therapy and achieved MRD negativity, but were lost to follow-up and are currently unreachable. These seven patients were included in the analysis with their last recorded visit at our institution serving as the final follow-up time. The most common mutations were FLT3-ITD, NPM1, DNMT3A, CEBPA and TET2. Two patients had the BCR-ABL P210 fusion gene. Of the patients with CEBPA mutations, 12 had double mutations and 20 had bzip mutations. As a result of the re-adjustment of risk stratification criteria in the 2022 ELN guidelines compared to 2017, there were 25 patients with a change in risk stratification. After induction therapy, 10 of FLT3-ITD positive patients were given sorafenib and 6 patients were given gilteritinib during consolidation therapy. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) were added to two Ph positive patients, one of which continued to take flumatinib, the other took imatinib first, and was changed to dasatinib due to treatment failure. Of the 20 patients who didn’t respond to initial induction therapy, 9 patients received the VA (venetoclax and azacitidine) regimen; 3 patients received the HVA (venetoclax, azacitidine and homoharringtonine) regimen; 4 patients received the FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, G-CSF) or CLAG (cladribine, cytarabine and G-CSF) regimen; 2 patients received the CAG (cytarabine, aclarubicin, and G-CSF) regimen; and 2 patients received the HA (homoharringtonine and cytarabine )regimen. A total of 35 patients received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation(Allo-HSCT).

Clinical outcomes

Tables 2 and 3 showed the outcomes of patients with different risk stratification. A total of 10 (5.7%) patients died during initial induction therapy and 20 patients did not respond(NR) to treatment. CRc and ORR after one cycle of DA/IA induction therapy were 81.1% and 82.8% respectively. 20 NR patients received re-induction therapy.

After 2 cycles of treatment, CRc and ORR were 89.1% and 90.2% respectively and 148 patients achieved CR. According to the 2017 ELN risk stratification, the ORR was 96.3% in patients with favourable risk, 89.2% in patients with intermediate risk, and 75% in patients with adverse risk(p = 0.0046). After re-stratification according to 2022 ELN recommendations, there was no significant change in ORR in each group compared with 2017 ELN recommendations. Among patients with CR, MRD-negativity was reached in 65.5% overall, and in the 2017 ELN risk stratification, 70.0% (54 of 77) in the favourable risk group, 62.3% (33 of 53) in the intermediate risk group, and 56% (10of 18) in the adverse risk group(p = 0.4138). However, the MRD-negativity was close after re-stratification. The median duration of MRD negative was 244 days(IQR 60–662). The median OS was 454 days(IQR 220–871).

The median OS of all patients was 454 days, 386 days in the favourable risk group, 482 days in the intermediate risk group and 398 days in the adverse risk group, respectively, according to the 2017 ELN recommendations. However, in the 2022 ELN recommendations, the median OS of patients in the favourable risk group, intermediate risk group, and adverse risk group was 514 days, 449days, and 411days, respectively. The OS of different prognostic stratification were statistically significant(2017 ELN p < 0.0001 vs. 2022 ELN p = 0.0003).

To explore the impact of age on efficacy within our cohort, we reanalyzed the data by dividing the patients into different age subgroups (Supplementary Table 1). After 2 cycles of induction therapy, the ORR across age groups were as follows: 100% in the < 20 years age group, 91.3% in the 20–29 years age group, 94.3% in the 30–39 years age group, 88.6% in the 40–49 years age group, and 88.2% in the 50–59 years age group. The MRD - duration was 244 days, 273 days, 278 days, 381 days, 212 days and 225 days respectively, and the median OS of patients was 454 days, 504 days, 550 days, 624 days, 442 days and 416 days respectively in different age group.

Second course of induction therapy

In NR patients after initial treatment, 2 patients were in the favourable risk group, 6 patients were in the adverse risk group, and 11 patients were in the intermediate risk group in both 2017 and 2022 ELN recommendations, In addition, one patient was in an intermediate-risk group in the 2017 ELN but in an adverse-risk group in the 2022 ELN.

Among the 20 patients with NR, there were 6 FLT3-ITD, 3 ASXL, 1 DNMT3A, 1 CEBPA bzip region, 1 TET2, 1 BCR-ABL P210, 1 IDH1, and 2 IDH2 mutation (Supplementary Table 2). Among the common genetic mutations, two patients with co-mutations of FLT3-ITD, NPM1, and DNMT3A experienced early death. Of the four patients with FLT3-ITD mutations who received venetoclax-based re-induction therapy, three achieved CR. Two patients underwent Allo-HSCT after CR1 and remained MRD-negative until the end of follow-up, with OS of 24.8 and 34.6 months, respectively. Four other patients with FLT3-ITD mutation didn’t receive Allo-HSCT due to limited economic conditions. Among them, two patients did not achieve remission continuously, and two achieved remission but later experienced disease relapse. All four patients died due to complications caused by disease progression.

Twelve of NR patients received a regimen containing venetoclax and azacitidine, while eight patients received a chemotherapy regimen without venetoclax. 7 patients still did not respond to therapy and five of the patients died from AML progression. In the treatment group containing venetoclax, 7 patients achieved CR, 1 patient achieved CRi, and 2 patients achieved NR. One patient died from septic shock. The CR rate of re-induction therapy was 58.3%, CRc and ORR were 66.7%. In the treatment group without venetoclax, 4 patients achieved CR, 1 patient achieved PR, and 2 patients achieved NR. One patients with HA died from gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The CRc and CR rate of reinduction therapy were 50%, ORR were 63% (Table 4).

Safety

The adverse effects(AEs) of all patients during induction therapy are shown in Table 5. The most common AEs were haematological AEs (100%), including leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia, and most of them were grade 3–4. Other common AEs include infection(95.4%), fatigue(74.9%), nausea(42.9%), hemorrhage(19.4%), electrolyte disturbances(hypocalcemia 19.4%, hypokalemia 17.7%), diarrhea(16.0%), and vomiting(14.3%) etc. Among these patients with infections, 9.7% were grade 2, 73.7% were grade 3, 6.9% were grade 4, and 5.1% were grade 5. Other AEs were mainly grade 1 and grade 2. A total of 10 patients died from the first cycle of induction therapy, including 7 patients who died from severe infection (6 patients with severe pneumonia, 1 patient with digestive tract infection) and 3 patients who died from major organ bleeding (2 patients with cerebral hemorrhage and 1 patient with digestive tract hemorrhage). Three patients died during re-induction therapy, two with VA died of septic shock and the other with HA died of gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

We compared the incidence of adverse reactions according to re-induction therapy regimens (Supplementary Table 3). Both groups experienced 100% incidence of grade 4 leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and grade 3 anemia. However, with the exception of diarrhea and oral mucositis, which were observed in the venetoclax-based re-induction group, other adverse events occurred more frequently and with higher severity in the intensified chemotherapy group.

Discussion

Daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 on day 1–3 combined with cytarabine 100 to 200 mg/m2 on day 1–7, the standard 3 + 7 regimen, is the first-line induction regimen for young adult AML patients, with a CR rate of 59–75%4,5,19,20,21. The same therapeutic effect can be achieved by replacing erythromycin with idarubicin7. However, some patients did not respond to the standard 3 + 7 regimen. Purine-based induction regimens (i.e., fludarabine or cladribine) compared with DA regimens have improved response rates to 67-85% after one cycle and 84% after 2 cycles, but survival rates are still unsatisfactory8,22,23,24. The combination of homoharringtonine and cytarabine was effective in the treatment of newly diagnosed AML, and the three-drug regimen of homoharringtonine combined with cytarabine and aclarubicin (HAA) further increased the complete response rate to 79%25,26. With the appearance of BCL-2 inhibitors, venetoclax combined with chemotherapy further improved the induced remission rate. The CR rates of venetoclax plus FLAG, CLIA, HA and DA for newly diagnosed adult AML were 69%, 94%, 84.6% and 91%, respectively9,27,28,29. Previous studies have found that the outcome of induction therapy is associated with the prognosis of AML30,31. Among the patients who didn’t achieve remission after DA or IA induction therapy, the CR rates of low dose, intermediate-dose and high dose cytarabine-based reinduction therapy were 56.4%, 53.3% and 59.6%, respectively18. There are still some patients who do not achieve CR within two courses of treatment and eventually become refractory leukemia.

In our study, the CR rate and ORR of 175 young adult AML patients after one cycle treatment with IA or DA regimen were 77.1% and 82.8% respectively. The 20 patients who failed one induction therapy were replaced with other treatment regiments, and the ORR rate of the whole cohort reached 90.2% after two courses of induction therapy. The ORR after two course of induction therapy in our retrospective study was similar to the DAV induction regimen9. The patients who didn’t respond to initial induction therapy were replaced with another induction therapy. Among the 20 patients with NR, 8 of 12 patients(66.7%) treated with a regimen that included VA achieved CRc, and 4 of 8 patients (50%) treated with intensive chemotherapy achieved CRc. However, due to the small sample size and the lack of statistical significance, these findings warrant further exploration in larger real-world studies.

In subgroup analysis, patients in the adverse risk group were more likely to not respond to induction treatment. Among the common genetic mutations, Patients with FLT3-ITD mutations and ASXL1 mutations were less likely to achieve remission following DA/IA induction. However, of the four patients with FLT3-ITD mutations who received venetoclax-based re-induction therapy, three achieved CR. Although the sample size is limited, these findings suggest that venetoclax-based re-induction therapy may overcome resistance to DA induction.

The MRD negative rate detected by flow cytometry after DA or IA regimen induction therapy is approximately 43–70% after one cycle and and 56.0–70% after two cycles32,33,34. In our cohort, the MRD- rate after 2 cycles was 65.5%, which is consistent with previous studies. Although the difference of MRD- rate in different groups was not statistically significant, the MRD- rate in the favourable risk group was higher than that in the adverse risk group. The MRD negative duration was longer in the adverse risk group than in the intermediate group, which may be related to the fact that more patients in the adverse risk group received allo-HSCT.

In analysis of different age subgroups, younger patients demonstrated higher CR rates after induction therapy, with a CR rate of 100% observed in the < 20 years age group. Among patients who did not achieve remission, those who switched to a different re-induction therapy early had higher remission rates after two cycles, particularly in the younger subgroups. Patients under 40 years of age had a longer MRD negative duration and median overall survival (OS), which may be related to the higher transplantation rate in this group.

The most common AEs associated with standard DA or other intensive induction regimens were hematologic AEs, including neutropenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia2,23,25. The most common non-hematologic AE was infection. All patients in our study had grade 3–4 hematological AEs during induction therapy, and the most common non-hematologic AE was infection, which is consistent with the conclusions of previous studies. Most of the AEs can be improved by symptomatic supportive treatment. In DAV induction regimen, all patients had hematological adverse effects above grade 3, and the incidence of nausea, diarrhea, mucositis, rash, and hemorrhage were 100%, 24%, 51%, 6%, and 39%, respectively9. In our study, the incidence of hematologic toxicity was the same as that of DAV regimen in young adult, but non-hematologic toxicity was significantly reduced. Based on these findings, we propose that young AML patients could initially receive DA regimen induction therapy, and for those who do not achieve remission, switching to an alternative treatment regimen may help mitigate the non-hematological toxicities commonly associated with three-drug combination induction therapies. Previous study found that the early death rate of DA regimen is 4.5–5.5%, and the early death rate of our study is 5.7%, which is close to that of previous studies2. Early death was mainly associated with severe infection and bleeding.

Our study found that early replacement of induction therapy regimen when DA or IA regimen did not achieve remission in newly diagnosed young AML patients was conducive to improving the remission rate of induction therapy. Venetoclax-based re-induction therapy has the potential to further improve efficacy. In addition, there were fewer adverse effects in venetoclax-based re-induction therapy compared to intense chemotherapy. We recommend that young patients with newly diagnosed AML be primarily treated with DA/IA induction therapy. For those who fail to achieve remission, early replacement of re-induction therapy enhances the therapeutic efficacy of newly diagnosed young adult AML. Based on the comparison of efficacy and adverse reactions, venetoclax-based re-induction therapy may represent a better therapeutic option; however, confirmation through larger studies with more robust sample sizes is warranted. There are still nearly 10% of patients can not achieve remission, and how to overcome the problem of induction therapy resistance in this part of patients is worthy of further exploration.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a retrospective analysis of untreated AML patients admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University from January 2020 to March 2024. The eligible patients were identified by bone marrow examination as having previously untreated new acute myeloid leukemia according to the criteria presented by WHO. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia were excluded. Each patient’s Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was less than 2. Patients with previous hematological malignancies, other malignancies, central nervous system involvement and active hepatitis were also excluded. Complete blood counts (CBCs), blood biochemical examination, electrocardiograms, cardiac ultrasound, and lung CT scans were conducted before induction therapy. According to Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of adult acute myeloid leukaemia (2017) ,each patient was eligible for intensive induction chemotherapy35. All patients received bone marrow morphology, karyotype, flow cytometry, fusion gene, and next generation sequencing(NGS) examination and were stratified for prognostic risk according to 2017 European Leukemia Net (ELN) recommendations36. We also re-stratified prognostic risk according to 2022 ELN recommendations17. All patients received at least induction therapy and experienced at least one bone marrow evaluation after therapy. Patients were evaluated by bone marrow morphology and minimal residual disease (MRD) examination after one cycle of induction therapy. MRD was evaluated by flow cytometry. MRD-positive as MRD ≥ 0.1% and MRD‐negative was defined as MRD < 0.1%. Survey data were collected from electronic records and all patients provided informed consent.

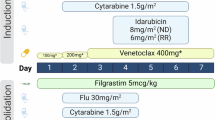

Treatment

The schema was shown in Fig. 1. All patients received IA or DA regimen induction therapy consisting of intravenous daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 or idarubicin 12 mg/m2 daily on days 1–3, cytarabine 200 mg/m² was divided into two subcutaneous injections daily on days 1–7. Patients with FLT3-ITD mutations were not treated with FLT3 inhibitors during induction therapy because midostaurin was not available in China and gilteritinib was approved only for relapsed or refractory AML. Following one cycle of induction therapy, patients who achieved CR and CRi (CR with incomplete blood cell count recovery) were categorized into consolidation therapy based on their risk stratification, in which patients who were eligible for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and had suitable donors and transplant intentions received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Patients who achieved PR were re-induced with the original regimen. Patients who did not achieve PR subsequently treated with other intense chemotherapy regimen or regimen that included venetoclax and azacitidine. All patients had at least two cycles of chemotherapy (with the exception of those who died early).

Outcome

The primary endpoint of this study was the composite CR(CRc) and overall response rate(ORR) after induction therapy. CRc including CR and CRi. ORR encompasses the total rates of CR, CRi and PR patients. The remission criteria followed the modified International Working Group response criteria for acute myeloid leukaemia37. The secondary endpoint was MRD-negative CRc rate after one cycle of induction therapy, the early death rate, MRD negative rate and overall survival(OS). Early mortality rate is defined as the rate of death within 30 days after chemotherapy. Overall survival represents the duration from treatment initiation to eventual death from any cause.

Adverse events(AEs) were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Statistical analysis

Population characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics.The chi-squared tests were used to compare differences between groups. OS were described by the Kaplan-Meier curve and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. All p-values are two-sided, with a significance level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS 26) and GraphPad Prism 9.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study are not available because of privacy and ethical restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to JS, sui_jc@163.com. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Yates, J. W., Wallace, H. J. Jr, Ellison, R. R. & Holland, J. F. Cytosine arabinoside (NSC-63878) and Daunorubicin (NSC-83142) therapy in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 57 (4), 485–488 (1973).

Fernandez, H. F. et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl. J. Med. 361 (13), 1249–1259 (2009).

Yates, J. et al. Cytosine arabinoside with Daunorubicin or adriamycin for therapy of acute myelocytic leukemia: a CALGB study. Blood 60 (2), 454–462 (1982).

Lee, J. H. et al. Cooperative study group A for hematology. A randomized trial comparing standard versus high-dose Daunorubicin induction in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 118 (14), 3832–3841 (2011).

Burnett, A. K. et al. A randomized comparison of Daunorubicin 90 mg/m2 vs 60 mg/m2 in AML induction: results from the UK NCRI AML17 trial in 1206 patients. Blood 125 (25), 3878–3885 (2015).

Murphy, T. & Yee, K. W. L. Cytarabine and Daunorubicin for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 18 (16), 1765–1780 (2017).

Lee, J. H. et al. Cooperative study group A for hematology. Prospective randomized comparison of Idarubicin and High-Dose Daunorubicin in induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 35 (24), 2754–2763 (2017).

Holowiecki, J. et al. Cladribine, but not fludarabine, added to Daunorubicin and cytarabine during induction prolongs survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a multicenter, randomized phase III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 (20), 2441–2448 (2012).

Wang, H. et al. Venetoclax plus 3 + 7 Daunorubicin and cytarabine chemotherapy as first-line treatment for adults with acute myeloid leukaemia: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 9 (6), e415–e424 (2022).

DiNardo, C. D. et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl. J. Med. 383 (7), 617–629 (2020).

Wei, A. H. et al. Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Blood 135 (24), 2137–2145 (2020).

Pollyea, D. A. et al. Venetoclax with Azacitidine or decitabine in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: long term follow-up from a phase 1b study. Am. J. Hematol. 96 (2), 208–217 (2021).

DiNardo, C. D. et al. 10-day decitabine with venetoclax for newly diagnosed intensive chemotherapy ineligible, and relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia: a single-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 7 (10), e724–e736 (2020).

Wei, A. H. et al. Venetoclax combined with low-dose cytarabine for previously untreated patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results from a phase Ib/II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 37 (15), 1277–1284 (2019).

Suo, X. et al. Venetoclax combined with Daunorubicin and cytarabine (2 + 6) as induction treatment in adults with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: a phase 2, multicenter, single-arm trial. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 12 (1), 45 (2023).

He, H., Wen, X. & Zheng, H. Efficacy and safety of venetoclax-based combination therapy for previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Hematology 29 (1), 2343604 (2024).

Döhner, H. et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 140 (12), 1345–1377 (2022).

Fu, W. et al. Re-induction therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia not in complete remission after the first course of treatment. Ann. Hematol. 102 (2), 329–335 (2023).

Brunnberg, U. et al. Induction therapy of AML with ara-C plus Daunorubicin versus ara-C plus Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin: a randomized phase II trial in elderly patients. Ann. Oncol. 23 (4), 990–996 (2012).

Récher, C. et al. Groupe Ouest-Est d’ étude des Leucé Mies Aiguës et autres. Long-term results of a randomized phase 3 trial comparing Idarubicin and Daunorubicin in younger patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 28 (2), 440–443 (2014).

Röllig, C. et al. Study alliance leukaemia. Addition of Sorafenib versus placebo to standard therapy in patients aged 60 years or younger with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukaemia (SORAML): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 16 (16), 1691–1699 (2015).

Borthakur, G. et al. Retrospective comparison of survival and responses to fludarabine, cytarabine, GCSF (FLAG) in combination with Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (GO) or Idarubicin (IDA) in patients with newly diagnosed core binding factor (CBF) acute myelogenous leukemia: MD Anderson experience in 174 patients. Am. J. Hematol. 97 (11), 1427–1434 (2022).

Jabbour, E. et al. A randomized phase 2 study of Idarubicin and cytarabine with Clofarabine or fludarabine in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 123 (22), 4430–4439 (2017).

Burnett, A. K. et al. Optimization of chemotherapy for younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of the medical research Council AML15 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 31 (27), 3360–3368 (2013).

Jin, J. et al. Homoharringtonine in combination with cytarabine and aclarubicin resulted in high complete remission rate after the first induction therapy in patients with de Novo acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 20 (8), 1361–1367 (2006).

Duan, W. et al. Comparison of efficacy between Homoharringtonine, aclarubicin, cytarabine (HAA) and Idarubicin, cytarabine (IA) regimens as induction therapy in patients with de Novo core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 102 (10), 2695–2705 (2023).

DiNardo, C. D. et al. Venetoclax combined with FLAG-IDA induction and consolidation in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 97 (8), 1035–1043 (2022).

Kadia, T. M. et al. Venetoclax plus intensive chemotherapy with Cladribine, Idarubicin, and cytarabine in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukaemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: a cohort from a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 8 (8), e552–e561 (2021).

Song, B. Q. et al. Outcomes of venetoclax combined with Homoharringtonine and cytarabine in fit adults patients with de Novo adverse-risk acute myeloid leukaemia: a single-centre retrospective analysis. EJHaem 4 (4), 1208–1211 (2023).

Walter, R. B. et al. Number of courses of induction therapy independently predicts outcome after allogeneic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first morphological remission. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 21 (2), 373–378 (2015).

Wu, S. et al. Prognosis of patients with de Novo acute myeloid leukemia resistant to initial induction chemotherapy. Am. J. Med. Sci. 351 (5), 473–479 (2016).

Ding, J. et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: the single-center experience of 668 patients in China. Hematology 29 (1), 2310960 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Prognostic value of platelet recovery degree before and after achieving minimal residual disease negative complete remission in acute myeloid leukemia patients. BMC Cancer. 20 (1), 732 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Relation of clinical response and minimal residual disease and their prognostic impact on outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 33 (11), 1258–1264 (2015).

Leukemia & Lymphoma Group, Chinese Society of Hematology, Chinese Medical Association. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of adult acute myeloid leukemia (not APL) (2017). Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 38 (3), 177–182 (2017). Chinese.

Döhner, H. et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 129 (4), 424–447 (2017).

Creutzig, U. & Kaspers, G. J. Revised recommendations of the international working group for diagnosis, standardization of response criteria, treatment outcomes, and reporting standards for therapeutic trials in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 22 (16), 3432–3433 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Translational Research Grant of HCRCH (2020ZKMB06), the Xingliao Talents Program (xlyc1807265) and Liaoning Province Central Guidance Special Project for Local Science and Technology Development (2023JH6/100200006). The funder didn’t participate in study design, data collection, data analysis, data visualization, or writing of the manuscript. No financial support was used for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and ZX: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing original draft. LZ, YJ and RB: data curation, methodology and writing original draft. DP: data curation, methodology, review and editing. XY: funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, resources, review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies were approved by the First Hospital of China Medical University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sui, J., Xu, Z., Zhang, L. et al. Early replacement of re-induction therapy following failed intensive induction treatment enhances the therapeutic efficacy of newly diagnosed AML. Sci Rep 15, 20022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04139-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04139-5