Summary

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by the Brucella spp., and the enhancement of diagnostic techniques is imperative for effective disease control. Currently, the diagnosis of brucellosis predominantly relies on serological tests, bacterial culture, and molecular biology methods. Among these approaches, serological diagnosis is the most widely utilized due to its relative simplicity. However, existing diagnostic antigens encounter challenges, such as cross-reactivity. Consequently, the development of novel antigens with high specificity and sensitivity is essential to improve the accuracy and efficiency of serological diagnosis for brucellosis. In this study, five antigenic proteins—Erythritol kinase, Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK), Adenosylhomocysteinase, the 31 kDa immunogenic protein, and Lyso-ornithine lipid O-acyltransferase—were selected, and B-cell linear epitopes were predicted using bioinformatics tools. Four prediction tools, namely ABCpred, SVMTriP, BCPred, and Bepipred Linear Epitope Prediction 2.0, were employed to screen for overlapping candidate epitopes. Fusion proteins were constructed through prokaryotic expression to serve as antigens for serological diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity of the fusion protein were evaluated using indirect ELISA to detect human IgG antibodies in serum samples. The results indicated that the fusion protein achieved sensitivity and specificity values of 0.8095 and 0.9949, respectively. Although these values were lower in comparison to traditional antigens such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the Rose Bengal antigen, the fusion protein exhibited improved cross-reactivity. This study successfully developed a multiepitope fusion protein for the diagnosis of brucellosis, thereby providing a foundation for the creation of highly specific and sensitive diagnostic antigens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by Brucella spp., which poses a significant threat to both animal husbandry and public health1,2,3. In recent years, the rapid expansion of global livestock industries and increased international trade have broadened the epidemiological landscape of brucellosis, resulting in rising incidence rates in certain regions4,5,6,7. The clinical manifestations of brucellosis, including fever, joint pain, and fatigue, are nonspecific and can easily be misattributed to other diseases, thereby complicating diagnosis and management8. Consequently, it is imperative to enhance the monitoring and control measures for brucellosis to safeguard public health and promote the sustainable development of livestock industries.

Currently, the diagnosis of brucellosis predominantly depends on serological tests, bacterial culture, and molecular biology techniques9,10. Serological tests are extensively utilized due to their simplicity and relative cost-effectiveness. However, these tests exhibit limitations, including the cross-reactivity of diagnostic antigens and inadequate sensitivity11. Bacterial culture is considered the gold standard for diagnosing brucellosis; nevertheless, it is a time-consuming and technically complex process that necessitates advanced laboratory conditions12. While molecular biology techniques offer high specificity and sensitivity, they are often prohibitively expensive and not suitable for large-scale screening13. Therefore, it is imperative to address the limitations associated with serological diagnostic antigens by developing highly specific diagnostic antigens to enhance the serological diagnosis of brucellosis.

This study aimed to predict linear B-cell epitopes of Brucella antigenic proteins utilizing bioinformatics methodologies and to construct a multiepitope fusion protein to enhance the accuracy of serological diagnosis for brucellosis. Key antigenic proteins from Brucella were selected, and multiple prediction tools were employed for epitope identification. Overlapping candidate epitopes were subsequently screened, and fusion protein was constructed and optimized for expression in Escherichia coli. The potential application of the fusion protein for the diagnosis of brucellosis was then evaluated using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA).

Materials and methods

Ethical approval statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University (approved number: xzhmu-2024Z052) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Serum samples

A total of 189 brucellosis-positive sera and 196 negative sera were collected, including 100 positive sera from Xuzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention and 89 positive sera from Shandong Province Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. All 196 negative serum samples were provided by Xuzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention. All samples were validated using the standard agglutination test (SAT, 231116, TSINGTAO SINOVA-HK BIOTECHNOLOGY, Qingdao, China), samples exhibiting a titre of 1:100 or greater were classified as positive for brucellosis. Furthermore, sera from 40 febrile patients who did not have Brucella infections (details are provided in Supplementary Information 1) were included to evaluate cross-reactivity.

Prediction of B-Cell epitopes

In this study, five Brucella antigenic proteins were selected: Erythritol kinase, Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK), Adenosylhomocysteinase, the 31 kDa immunogenic protein, and Lyso-ornithine lipid O-acyltransferase. B-cell linear epitopes were predicted utilizing bioinformatics methodologies as outlined below:

The amino acid sequences of the proteins were retrieved from the Protein database available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/). Additionally, conserved sequences of Brucella were identified through a comparative analysis using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). To enhance the accuracy of B-cell epitope prediction, four distinct B-cell epitope prediction tools were employed for analysis. These tools include ABCpred (https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/abcpred/index.html), SVMTriP (http://sysbio.unl.edu/SVMTriP), BCPred (http://ailab-projects2.ist.psu.edu/bcpred/predict.html), and the Bepipred Linear Epitope Prediction 2.0 (http://tools.iedb.org/bcell/). The B-cell epitopes predicted by each tool were compiled and compared, with overlapping epitopes being selected as candidate epitopes.

Construction of amino acid sequences for multiepitope fusion protein

Following the prediction of epitopes, the candidate epitopes were concatenated into a singular sequence. Epitopes were arranged in the order they appeared in the original protein sequences. A linker ‘GGGS’ sequence was included between adjacent epitopes primarily to ensure proper folding and to avoid potential steric hindrance.

Evaluation of the properties of multiepitope fusion protein

The isoelectric point (pI) and molecular weight (MW) of the fusion protein’s amino acid sequence were predicted using the ProtParam tool available on the ExPASy website (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). This analysis aimed to assess the physicochemical properties of the fusion protein. Additionally, the three-dimensional molecular model of the fusion protein was generated using the I-TASSER platform (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) to evaluate its spatial conformation. The solubility and antigenicity of the fusion protein were predicted and assessed using the recombinant protein solubility prediction tool (www.biotech.ou.edu) and VaxiJen software (http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/vaxijen/VaxiJen/VaxiJen.html).

Molecular Docking and molecular dynamics simulation

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of the fusion protein was predicted using the Boltz-1 model, and the optimal conformation, designated as FP0, was selected based on the confidence score of the predicted model. The crystal structure of the human IgG Fab fragment (PDB ID: 5I19) was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). Rigid-body molecular docking between FP0 and 5I19 was conducted using ZDOCK 3.0.2, with the Z-score serving as the binding affinity metric to identify the most favorable complex configuration. The docking complex with the highest Z-score was chosen for all-atom molecular dynamics simulation. The molecular dynamics simulation was performed using GROMACS software, employing the amber03 force field and the SPC water model, with a simulation duration set to 100 ns. Trajectories were generated, and fluctuation analysis was conducted during the simulation.

Preparation of fusion protein

The amino acid sequence was reverse-translated to optimize codon usage, thereby enhancing expression in Escherichia coli. A 6×His tag was appended to the C-terminal end to facilitate purification. The gene encoding the fusion protein was synthesized by a commercial biotechnology firm (Beijing Protein Innovation Co., Ltd.), subsequently cloned into the pET30a expression vector, and transformed into BL21 competent cells to enable prokaryotic expression. The detailed procedures are outlined as follows:

BL21cells that had been stored at -80 °C were gradually thawed on ice. The cells were then mixed with the ligation product while remaining on ice for a duration of 30 min, followed by a heat shock at 42 °C for 90 s. Subsequently, the cells were placed in an ice bath for 2 min, after which 800 µL of LB medium devoid of antibiotics was added, and the mixture was cultured at 37 °C for 45 min. Following centrifugation at 3214×g (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810R, Germany) for 3 min, the supernatant was discarded, leaving approximately 100–150 µL of the cell suspension. The bacteria were then resuspended and spread onto LB plates containing the appropriate antibiotic resistance. After allowing the plates to dry, they were incubated overnight in a 37 °C incubator. Single colonies from the transformed plates were selected and cultured in 250 mL of LB liquid medium at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6–0.8 was reached. Induction was performed using IPTG (0.5 mM) at 37 °C for 4 h. Following centrifugation at 8228×g for 6 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the bacterial cells were collected. The cells were then resuspended in 20–30 mL of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) solution and subjected to sonication (500 W, 180 cycles, 5 s each with a 5-second interval).

Nickel affinity columns (Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow, GE Healthcare) were initially washed with deionized water to achieve a pH of 7.0. Subsequently, the nickel was adjusted to a pH range of 2 to 3. The column was then washed again with deionized water to restore a pH of 7.0. Following this, the nickel column was equilibrated with approximately 100 mL of a 10 mM Tris-HCl solution at pH 8.0. An additional equilibration step was performed using approximately 50 mL of a 10 mM Tris-HCl solution at pH 8.0, which contained 0.5 M sodium chloride. The diluted sample, which also contained sodium chloride at a final concentration of 0.5 M, was subsequently loaded onto the column. After the sample loading, the column was washed with a 10 mM Tris-HCl solution at pH 8.0, supplemented with 0.5 M sodium chloride. The elution of protein peaks was achieved using 10 mM Tris-HCl solutions at pH 8.0, containing 15 mM, 60 mM, and 300 mM imidazole (with 0.5 M sodium chloride), with each protein peak being collected separately. The purity of the eluted protein was assessed using 12% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis.

Development of indirect ELISA method

The prepared fusion protein was utilized as a diagnostic antigen to develop an iELISA for the diagnosis of brucellosis. The specific methodology is outlined as follows:

The purified fusion protein was diluted to a concentration of 10 µg/mL using CBS and subsequently added to a 96-well microplate (Corning, USA) at a volume of 100 µL per well. The microplate was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Following this incubation, the wells were washed three times with PBST, after which a 5% skim milk blocking solution was introduced and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After another series of three washes with PBST, brucellosis serum and healthy human serum, both diluted at a ratio of 1:200, were added at a volume of 100 µL per well, with three replicate wells established for each serum type. The microplate was then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by three additional washes with PBST. Subsequently, an HRP- conjugated rabbit anti-human IgG secondary antibody (diluted 1:10,000, Thermo Fisher, USA) was added at a volume of 100 µL per well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing the wells three times with PBST, TMB chromogenic solution was added at a volume of 100 µL per well and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of a 2M H2SO4 stopping solution, and the OD450 was measured using a microplate reader (Versa Max microplate reader, MD, USA). Laboratory-stored LPS (provided by the China Animal Health and Epidemiology Center, 3 mg/mL) was diluted to a concentration of 10 µg/mL for the purpose of coating the plates and Rose Bengal Ag (suspension of Brucella abortus (Weybridge 99 strain), diluted 1:400, IDEXX Pourquier, Montpellier, France) served as control antigens, and serum samples were tested in triplicate following the same protocol. Sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC), and the cut-off value were determined through receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis.

Evaluation of Cross-Reactivity in the indirect ELISA method

Following the procedure outlined above, sera from febrile patients who were not diagnosed with brucellosis were analyzed using the two antigens to assess the cross-reactivity of the constructed fusion protein. The evaluation of cross-reactivity was conducted based on the cut-off value established by the ROC curve.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses, including ROC curve assessments and dot plot evaluations, were conducted utilizing GraphPad Prism version 6.05. Differences between groups were evaluated using unpaired Student’s t-tests, with a p-value of less than 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

Results

Prediction of B-Cell epitopes

A total of five antigenic proteins were selected for analysis, resulting in the prediction of 28 B-cell epitopes. These epitopes are distributed among the following proteins: Erythritol kinase (7 epitopes), Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (2 epitopes), Adenosylhomocysteinase (6 epitopes), Brucella cell surface 31 kDa protein (BCSP31) (7 epitopes), and Lyso-ornithine lipid O-acyltransferase (6 epitopes). The specific details of the predicted epitopes are presented in Table 1.

Construction and evaluation of fusion protein

The predicted B-cell epitopes derived from each outer membrane protein were concatenated using the linker “GGGS” sequence to form a singular sequence. The resultant multiepitope fusion protein comprised 402 amino acids. Figure 1A illustrates the specific amino acid sequence of the fusion protein.

The physicochemical properties of the fusion protein were predicted utilizing the ProtParam tool available on the ExPASy platform. The results indicated that the pI of the recombinant Brucella multiepitope fusion protein was 5.18, and its molecular weight was determined to be 37.5 kDa. Solubility predictions conducted using the website www.biotech.ou.edu suggested that the protein might be expressed as inclusion bodies within a prokaryotic system. The antigenicity score, calculated using the VaxiJen tool, was 1.622, which suggests that the fusion protein has the potential to serve as an effective antigen capable of eliciting an immune response. The 3D molecular structure of the fusion protein, as predicted by I-TASSER, is illustrated in Fig. 1B.

Molecular Docking and molecular dynamics simulation results

The molecular docking results (Fig. 2A) indicated that FP0 bound to 5I19 through several non-covalent interactions: (1) a hydrophobic interaction network, which includes the H chain Tyr103 interacting with the A chain Leu29, and the L chain Tyr49 interacting with the A chain Leu27, among others; (2) a cation-π interaction, where the aromatic ring of H chain Tyr32 formed a stable stacking with the guanidinium group of A chain Arg326.

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using GROMACS software. The thermodynamic equilibrium analysis of the system (Fig. 2B) demonstrated that the temperature remained stable throughout the simulation, indicating effective control over the thermodynamic conditions and ensuring the reliability of the results. The potential energy curve (Fig. 2C) decreased by approximately 4 × 10^4 kJ/mol during the initial relaxation phase and subsequently stabilized, signifying that the system reached an energy equilibrium state. The RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) results (Fig. 2D) indicated that the protein underwent initial conformational adjustments during the simulation, followed by fluctuations within a specific range and eventual stabilization, suggesting that the complex conformation entered a dynamic equilibrium phase. The RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) results (Fig. 2E) displayed the residue fluctuations of the three protein chains (A, L, and H). The three chains exhibited varying degrees of fluctuation in different regions, with higher RMSF values indicating flexible regions or areas near active sites, while lower RMSF values suggested relatively stable residues that may constitute the structural core of the protein. The dynamic characteristics of the complete trajectory are presented in the supplementary video material (Additional file 3).

Preparation of fusion protein

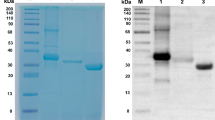

The multiepitope fusion protein was successfully expressed in a prokaryotic system and subsequently purified. The target protein exhibited a molecular weight of approximately 66 kDa. Analysis via SDS-PAGE indicated that the purity of the protein surpassed 90%, a finding corroborated by densitometric measurements. The outcomes of the protein purification process are illustrated in Fig. 3 and Figure S1 (Additional file 1).

Results of IELISA

The analysis of the ROC curve indicates that the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the fusion protein is 0.9537 (95% CI: 0.9334 to 0.9740), demonstrating that the fusion protein effectively detects human IgG antibodies against Brucella which is marginally lower than that of LPS and Rose Bengal antigen. The calculation of the Youden index reveals that the sensitivity of the fusion protein is 0.8095, while the specificity is 0.9949. Although these sensitivity and specificity values are slightly inferior to those of LPS and Rose Bengal antigen, the fusion protein demonstrates satisfactory performance in the diagnosis of brucellosis. The detailed results are provided in Table 2; Fig. 4, and Additional File 2.

TP, true positives; TN, true negatives; FP, false positives; FN, false negatives; Accuracy, (TP + TN/TP + FN + TN + FP) ×100; PPV, positive predictive value (TP/TP + FP) ×100; NPV, negative predictive value (TN/TN + FN) ×100.

Cross-reactivity assessment

The study employed the iELISA to evaluate cross-reactivity among serum samples from clinical febrile patients without brucellosis, utilizing established cut-off values. Cross-reactivity was identified in 5 out of 40 serum samples tested with the fusion protein, specifically involving 2 cases of Escherichia coli, and 1 case each of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecium. In contrast, cross-reactivity with LPS and Rose Bengal antigen was observed in 16 and 18 cases, respectively. The pathogens exhibiting cross-reactivity with LPS and Rose Bengal antigen were predominantly Escherichia coli. Notably, cross-reactivity with LPS encompassed 8 cases of Escherichia coli infection, 3 cases of Staphylococcus aureus, and 1 case each of Enterococcus faecium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Moraxella osloensis, Pseudomonas putida, and Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Furthermore, cross-reactivity with Rose Bengal antigen was documented in 18 cases, which included 7 cases of Escherichia coli infection, 2 cases each of Enterococcus faecium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, and as well as case each of Aeromonas sobria, Moraxella osloensis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas putida, and Rothia mucilaginosa. The details are shown presented Additional File 2.

Discussion

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the development of diagnostic tools for brucellosis. Advances in molecular techniques, such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have improved the detection of Brucella spp. in clinical samples14,15. Additionally, novel immunochromatographic strips have been developed for rapid diagnosis16,17. However, these techniques are often limited by their complexity and cost, making ELISA-based methods still highly relevant for large-scale screening18. The ELISA is a pivotal tool in the serological diagnosis of brucellosis. This assay is characterized by its simplicity, rapid testing capabilities, high specificity, and minimal sample requirements, rendering it suitable for both high-throughput screening and confirmatory testing. Consequently, ELISA has been extensively utilized for the diagnosis of brucellosis in human and animal populations19,20. However, despite its numerous advantages, ELISA encounters challenges such as cross-reactivity, which can adversely affect the specificity of diagnostic outcomes. For instance, diagnostic antigens for brucellosis may exhibit cross-reactivity with Yersinia enterocolitica O9, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other bacteria21,22,23,24. Therefore, the development of novel antigens with enhanced specificity and sensitivity is imperative for improving the accuracy and efficiency of brucellosis diagnosis.

In this study, five critical antigenic proteins—Erythritol kinase, Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK), Adenosylhomocysteinase, the 31 kDa immunogenic protein, and Lyso-ornithine lipid O-acyltransferase—were subjected to analysis. These proteins are integral to the pathogenesis and immune response associated with Brucella, thus making them suitable candidates for B-cell epitope prediction. Erythritol kinase, which is encoded by the eryA gene, is an enzyme composed of 519 amino acids25,26. This enzyme catalyzes the ATP-dependent conversion of erythritol to L-erythritol-4-phosphate. Its activity is essential for the metabolic processes of Brucella and is closely associated with bacterial pathogenicity27. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK) is a multifunctional enzyme that plays a critical role in nucleotide metabolism and is central to the biology of Brucella. Experimental studies in animals have demonstrated that recombinant NDK induces both humoral and cellular immune responses, thereby enhancing protective efficacy in experimental mice28,29. These findings suggest that NDK may serve as a promising candidate for a subunit vaccine against brucellosis30,31. Adenosylhomocysteinase facilitates the hydrolysis of S-adenosylhomocysteine into homocysteine and adenosine, thereby regulating intracellular methylation levels. This regulation is essential for the proper methylation modification of various biomolecules in Brucella. Furthermore, it plays a critical role in the metabolic control, growth, and interaction of Brucella with host cells, offering valuable insights into pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets32. The BCSP31 is a well-characterized immunogenic protein found on the surface of Brucella species. This protein has been extensively studied due to its significant role in the immune response elicited by Brucella infections and its potential applications in the diagnosis and vaccine development for brucellosis33,34. During Brucella infection, this protein interacts with the host’s immune defense mechanisms and serves as a crucial biological marker for the development of Brucella vaccines and the diagnosis of infections14,35. Lyso-ornithine lipid O-acyltransferase plays a crucial role in the lipid metabolic pathway associated with the cell membrane of Brucella36,37. This enzyme is responsible for the transfer of acyl groups to lyso-ornithine lipids, which is essential for the construction of the Brucella cell membrane. It contributes to the maintenance of membrane integrity, regulation of membrane fluidity, and participation in cell signal transduction. Furthermore, this enzyme is closely linked to the survival, invasion, and pathogenic processes of Brucella within the host, making it a potential target for investigations into the biological characteristics of Brucella’s cell membrane and the development of antibacterial strategies.

The prediction of B-cell epitopes for these proteins offers a theoretical foundation for the creation of effective diagnostic tools. In this study, we employed four bioinformatics tools to predict B-cell epitopes of Brucella antigenic proteins: ABCpred38, SVMTriP39, BCPred40, and Bepipred Linear Epitope Prediction 2.041. ABCpred utilizes a prediction methodology based on artificial neural networks, demonstrating high accuracy in the identification of B-cell epitopes, and its use in the prediction of epitopes in the Brucella L7/L12 protein has been reported42. SVMTriP enhances the performance of B-cell epitope prediction, achieving a sensitivity of up to 80.1% during five-fold cross-validation, thereby providing a robust approach for antigen epitope prediction, it has been successfully used for epitope prediction of Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis43,44. Additionally, BCPred and Bepipred Linear Epitope Prediction 2.0 are recognized as effective tools for predicting linear B-cell epitopes and are successfully used in the design of vaccine and diagnostic antigen45,46.

By integrating the predictions from these four tools, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of B-cell epitopes associated with Brucella antigenic proteins and selected candidate epitopes by comparing the overlapping regions of the predicted outcomes from each tool. This integrative approach significantly improved the accuracy and reliability of our predictions. The predicted epitopes were subsequently validated through experimental methods, confirming the efficacy of the selected tools and methodologies in predicting Brucella epitopes. The design of the multiepitope fusion protein in this study did not specifically optimize the order of epitopes or the choice of linkers. The epitopes were arranged based on their appearance in the original protein sequences, and a generic linker was used to ensure proper folding. While this approach allowed for the successful construction and expression of the fusion protein, it may not have maximized the antigenicity or minimized cross-reactivity. Future work should consider optimizing the epitope order based on immunogenicity scores and incorporating linkers with specific lengths and sequences to enhance spatial separation and stability. Additionally, computational modeling of the fusion protein structure could provide insights into potential improvements in epitope arrangement and linker design. The incorporation of bioinformatics approaches, including 3D structure prediction, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation, significantly enhances our understanding of the fusion protein’s structural stability and binding interactions. These computational analyses provide insights into the conformational dynamics and key interaction sites, supporting the rational design of the fusion protein. The results from molecular dynamics simulations, in particular, highlight the dynamic equilibrium of the protein complex, suggesting robustness in its application for serological diagnosis. These bioinformatics studies not only validate the experimental design but also offer a foundation for further optimization of diagnostic antigens.

The computational simulation methods employed in this study, including the Boltz-1 model for predicting the three-dimensional structure of the fusion protein, ZDOCK 3.0.2 for molecular docking, and GROMACS software for molecular dynamics simulations, represent well-established tools in the field of structural biology and bioinformatics47,48. While these methods have been widely used and validated in numerous studies, it is important to acknowledge that they may not capture all aspects of the complex interactions between the fusion protein and antibodies. For instance, the Boltz-1 model, although reported to achieve precision comparable to AlphaFold 3 in predicting protein structures, may still have limitations in resolving fine details of protein conformation, particularly in dynamic or flexible regions. Similarly, ZDOCK 3.0.2, while efficient in rigid-body docking scenarios, may not fully account for conformational changes that occur during the binding process. The molecular dynamics simulations using GROMACS with the amber03 force field and SPC water model provide valuable insights into the stability and interaction patterns of the protein-antibody complex; however, the accuracy of these simulations can be influenced by factors such as force field parameters and simulation time49.

Through the application of genetic engineering techniques, a multiepitope fusion protein was successfully expressed and purified. The resulting purified protein, which has an approximate molecular weight of 66 kDa, demonstrated a high degree of purity and favorable solubility. Results from iELISA indicated that the fusion protein exhibited high sensitivity and specificity, although these metrics were lower than those observed for traditional antigens such as LPS and Rose Bengal antigen18. The AUC value of 0.9537 further substantiates the efficacy of the fusion protein for the diagnosis of brucellosis. Assessment of cross-reactivity revealed that LPS exhibited cross-reactivity with 16 different pathogens, including 8 instances of Escherichia coli infection. This phenomenon can be attributed to the structural similarities of LPS found in Gram-negative bacteria, which may lead to false-positive results and compromise the accuracy of diagnostic outcomes. Similarly, the Rose Bengal antigen also demonstrated cross-reactivity in the context of brucellosis diagnosis. In contrast, the fusion protein developed in this study comprises 28 predicted B-cell epitopes that are specific to Brucella, resulting in a lower rate of cross-reactivity compared to LPS and Rose Bengal antigen. Some of the predicted B-cell epitopes in the fusion protein may share structural or conformational similarities with epitopes present in other pathogens, leading to cross-reactivity. For example, the epitopes derived from the 31 kDa immunogenic protein (BCSP31) or Lyso-ornithine lipid O-acyltransferase may have partial homology with epitopes from Escherichia coli or other Gram-negative bacteria. Future studies could focus on refining the selection of epitopes by excluding those with high similarity to epitopes from common cross-reactive pathogens. The cross-reactivity could also be attributed to the polyclonal nature of the antibody response in patients, where antibodies targeting non-specific epitopes may bind to the fusion protein. Despite our efforts to purify the fusion protein using nickel affinity chromatography, residual host cell proteins or impurities in the preparation may contribute to non-specific reactions. Although this finding suggests that the fusion protein offers a significant advantage in enhancing diagnostic specificity, it is crucial to exercise caution during the purification process of the fusion protein, as incomplete purification may lead to non-specific reactions due to contamination from host cell proteins or other impurities. Such non-specific proteins could adversely affect the diagnostic specificity of the assay. The design of the fusion protein could be refined by incorporating specific linkers or modifying the order of epitopes to enhance spatial separation and reduce steric hindrance.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed a novel multiepitope fusion protein for the serological diagnosis of brucellosis, utilizing bioinformatics methodologies to predict antigenic regions and an indirect ELISA to specifically detect human IgG antibodies. The fusion protein exhibited substantial diagnostic potential, characterized by high sensitivity and specificity, while significantly minimizing cross-reactivity in comparison to conventional antigens such as LPS and Rose Bengal antigen. The incorporation of epitopes from Brucella proteins into the fusion protein demonstrated potential for improved specificity in serological diagnosis. However, cross-reactions observed with some non-Brucella patient sera indicate that the epitopes may not be entirely Brucella-specific. Further studies are needed to address this limitation and explore additional methods to enhance the specificity of the fusion protein for diagnostic applications. Nevertheless, several limitations were identified in this study. The relatively small sample size may impact the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, we collected samples that tested positive using serological methods; however, we did not obtain positive samples confirmed through bacterial culture. Our collection of supplementary patient sera did not include samples of Yersinia enterocolitica O9 or Escherichia coli O157:H7, both of which exhibit significant overlap with the serological diagnosis of brucellosis. Therefore, the next step requires the collection of relevant serum samples to validate the specificity of the synthesized fusion proteins. Future research should aim to incorporate larger sample sizes and further refine the design and expression conditions of the fusion protein to enhance diagnostic efficacy. Furthermore, the successful development and validation of this fusion protein establish a basis for future vaccine development and therapeutic strategies targeting brucellosis.

Figures and Figure Legends.

Data availability

All data required to evaluate the conclusions of this study are presented in the paper and/or Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Suárez-Esquivel, M., Chaves-Olarte, E. & Moreno, E. Guzmán-Verri, C. Brucella genomics: macro and micro evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7749 (2020).

Ali, S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of brucellosis in Asia: Insights from genotyping analyses. Vet. Res. Commun. 48, 3533–3550 (2024).

Nabi, I. et al. Serological, phenotypic and molecular characterization of brucellosis in small ruminants in Northern Algeria. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1505294 (2024).

Franco, M. P., Mulder, M., Gilman, R. H. & Smits, H. L. Human brucellosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 7, 775–786 (2007).

Pinn-Woodcock, T. et al. A one-health review on brucellosis in the united States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 261, 451–462 (2023).

Almuzaini, A. M. et al. Seroprevalence of brucellosis in camels and humans in the Al-qassim region of Saudi Arabia and its implications for public health. AMB Express. 15, 22 (2025).

Emmanouil, M. et al. Epidemiological investigation of animal brucellosis in domestic ruminants in Greece from 2015 to 2022 and genetic characterization of prevalent strains. Pathog (Basel Switz). 13, 720 (2024).

Qureshi, K. A. et al. Brucellosis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment-a comprehensive review. Ann. Med. 55, 2295398 (2023).

Freire, M. L., de Assis, M., Silva, T. S., Cota, G. & S. N. & Diagnosis of human brucellosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0012030 (2024).

Yagupsky, P., Morata, P. & Colmenero, J. D. Laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33, e00073–e00019 (2019).

Andrade, R. S. et al. Accuracy of serological tests for bovine brucellosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Vet. Med. 222, 106079 (2024).

Ml, F., Ts, M. A., Sn, S. & G, C. Diagnosis of human brucellosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 18, (2024).

Rahbarnia, L., Farajnia, S., Naghili, B. & Saeedi, N. Comparative evaluation of nested polymerase chain reaction for rapid diagnosis of human brucellosis. Arch. Razi Inst. 76, 203–211 (2021).

Becker, G. N. & Tuon, F. F. Comparative study of IS711 and bcsp31-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the diagnosis of human brucellosis in whole blood and serum samples. J. Microbiol. Methods. 183, 106182 (2021).

Zeybek, H., Acikgoz, Z. C., Dal, T. & Durmaz, R. Optimization and validation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction protocol for the diagnosis of human brucellosis. Folia Microbiol. 65, 353–361 (2020).

Novak, A. et al. Development of a novel glycoprotein-based immunochromatographic test for the rapid serodiagnosis of bovine brucellosis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 132, 4277–4288 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Rapid detection of brucellosis using a quantum dot-based immunochromatographic test strip. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008557 (2020).

Gusi, A. M. et al. Comparative performance of lateral flow immunochromatography, iELISA and Rose Bengal tests for the diagnosis of cattle, sheep, goat and swine brucellosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007509 (2019).

Loubet, P. et al. Diagnosis of brucellosis: Combining tests to improve performance. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0012442 (2024).

Lyimo, B. et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors for brucellosis amongst livestock and humans in a multi-herd ranch system in Kagera, tanzania. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1478494 (2024).

Bonfini, B. et al. Cross-reactivity in serological tests for brucellosis: a comparison of immune response of escherichia coli O157:H7 and yersinia enterocolitica O:9 vs brucella spp. Vet. Ital. 54, 107–114 (2018).

O’Grady, D., Kenny, K., Power, S., Egan, J. & Ryan, F. Detection of yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:9 In the faeces of cattle with false positive reactions in serological tests for brucellosis in Ireland. Vet. J. (Lond Engl. : 1997). 216, 133–135 (2016).

Lu, J. et al. Novel vertical flow immunoassay with Au@PtNPs for rapid, ultrasensitive, and on-site diagnosis of human brucellosis. ACS Omega. 8, 29534–29542 (2023).

Wu, Q. et al. Study on antigenic protein Omp2b in combination with Omp31 and BP26 for serological detection of human brucellosis. J. Microbiol. Methods. 205, 106663 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Expression and regulation of the ery Operon of brucella melitensis in human trophoblast cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 12, 2723–2728 (2016).

Barbier, T. et al. Erythritol feeds the Pentose phosphate pathway via three new isomerases leading to D-erythrose-4-phosphate in brucella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, 17815–17820 (2014).

Jf, S. & Dc, R. Inhibition of growth by erythritol catabolism in brucella abortus. J Bacteriol 124, (1975).

Hop, H. T. et al. Immunization of BALB/c mice with a combination of four Recombinant brucella abortus proteins, AspC, Dps, InpB and Ndk, confers a marked protection against a virulent strain of brucella abortus. Vaccine 36, 3027–3033 (2018).

Arayan, L. T. et al. Substantial protective immunity conferred by a combination of brucella abortus Recombinant proteins against brucella abortus 544 infection in BALB/c mice. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29, 330–338 (2019).

Yu, H., Rao, X. & Zhang, K. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (ndk): A pleiotropic effector manipulating bacterial virulence and adaptive responses. Microbiol. Res. 205, 125–134 (2017).

Rocha, R. O. & Wilson, R. A. Magnaporthe oryzae nucleoside diphosphate kinase is required for metabolic homeostasis and redox-mediated host innate immunity suppression. Mol. Microbiol. 114, 789–807 (2020).

Vande Voorde, J. et al. Metabolic profiling stratifies colorectal cancer and reveals adenosylhomocysteinase as a therapeutic target. Nat. Metab. 5, 1303–1318 (2023).

Saidu, A. S. et al. Studies on intra-ocular vaccination of adult cattle with reduced dose brucella abortus strain-19 vaccine. Heliyon 8, e08937 (2022).

de Carvalho, G. et al. Detection of brucella S19 vaccine strain DNA in domestic and wild ungulates from Brazilian Pantanal. Curr. Microbiol. 81, 333 (2024).

Jl, S., Aa, H., Lr, S. B. & Rs, K. S. Diagnostic utility of LAMP PCR targeting bcsp-31 gene for human brucellosis infection. Indian J. Med. Microbiol 44, (2023).

Palacios-Chaves, L. et al. Brucella abortus ornithine lipids are dispensable outer membrane components devoid of a marked pathogen-associated molecular pattern. PLOS One. 6, e16030 (2011).

Chain, P. S. G. et al. Whole-genome analyses of speciation events in pathogenic brucellae. Infect. Immun. 73, 8353–8361 (2005).

Malik, A. A., Ojha, S. C., Schaduangrat, N. & Nantasenamat, C. ABCpred: A webserver for the discovery of acetyl- and butyryl-cholinesterase inhibitors. Mol. Divers. 26, 467–487 (2022).

B, Y. & C, Z. D, Z., S, L. SVMTriP: a method to predict B-cell linear antigenic epitopes. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N J) 2131, (2020).

Zheng, D., Liang, S. & Zhang, C. B-cell epitope predictions using computational methods. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N J). 2552, 239–254 (2023).

Fernandes, J. D. et al. The UCSC SARS-CoV-2 genome browser. Nat. Genet. 52, 991–998 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Bioinformatics analysis of the antigenic epitopes of L7/L12 protein in the B- and T-cells active against brucella melitensis. Access. Microbiol. 6, 786v3 (2024).

Bernhardt, G. V., Bernhardt, K., Shivappa, P. & Pinto, J. R. T. Immunoinformatic prediction to identify staphylococcus aureus peptides that bind to CD8 + T-cells as potential vaccine candidates. Vet. World. 17, 1413–1422 (2024).

Pillay, K., Chiliza, T. E., Senzani, S., Pillay, B. & Pillay, M. Silico design of mycobacterium tuberculosis multi-epitope adhesin protein vaccines. Heliyon 10, e37536 (2024).

Wu, Q. et al. Preparation and application of a brucella multiepitope fusion protein based on bioinformatics and tandem mass tag-based proteomics technology. Front. Immunol. 15, 1509534 (2024).

Foroutan, M. & Shadravan, M. M. Completing the pieces of a puzzle: in-depth probing of Toxoplasma gondii Rhoptry protein 4 as a promising target for vaccination using an in-silico approach. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 13, 359–369 (2024).

Han, J. et al. Ligand and G-protein selectivity in the κ-opioid receptor. Nature 617, 417–425 (2023).

Kim, H. et al. Irisin mediates effects on bone and fat via ΑV integrin receptors. Cell 178, 507–508 (2019).

Conde, D., Garrido, P. F., Calvelo, M., Piñeiro, Á. & Garcia-Fandino, R. Molecular dynamics simulations of transmembrane Cyclic peptide nanotubes using classical force fields, hydrogen mass repartitioning, and hydrogen isotope exchange methods: A critical comparison. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 3158 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by Xuzhou Science and Technology Bureau (Grant number KC23306), the Medical Research Program of Jiangsu Commission of Health (Grant number Z2023080), QingLan Project of Jiangsu Province (2024). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GW, XQ and DY conceived and designed the study. XQ and DY performed the assays and drafted the manuscript. SZ, QP and YC were analyzed the data. TZ and GW reviewed and made improvements for the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University (approved number: xzhmu-2024Z052) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Qi, X., Zhao, S. et al. Preparation of a Brucella multiepitope fusion protein based on bioinformatics and its application in serological diagnosis of human brucellosis. Sci Rep 15, 19106 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04244-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04244-5