Abstract

The effective improvement of animal welfare requires quantitative methods to compare diverse impacts across practices and policies on a common, relatable scale. The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) fulfills this need by providing a standardized welfare impact measure: cumulative time in affective states of varying intensities. To this end, WFF estimates rely on documented syntheses of existing research, including behavioral, neurophysiological and pharmacological indicators. We apply this framework to quantify the welfare impact of air asphyxia during fish slaughter, using rainbow trout as a case study. Based on a review of research on stress responses during asphyxiation, we estimate 10 (1.9–21.7) min of moderate to intense pain per trout or 24 (3.5–74) min/kg. Cost-effectiveness modelling shows that electrical stunning could avert 60–1200 min of moderate to extreme pain per US dollar of capital expenditure, but commercial performance remains variable. Percussive stunning demonstrates reliable effectiveness, but still faces implementation challenges. These findings provide transparent, evidence-grounded and comparable metrics to guide cost–benefit decisions and inform slaughter regulations and practices in trout (and potentially other species). With over a trillion fish slaughtered annually, they also demonstrate the potential scale of welfare improvements achievable with effective stunning methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Societal concern about the impacts of production practices on animal welfare is rising, as evidenced by consumer-driven movements, labelling efforts, accreditation schemes, policies and legislation that prioritize animal welfare1. The need to consider animal welfare within sustainability assessments is also increasingly recognized2,3, as environmental gains cannot be justified if they occur at the expense of animal welfare.

While environmental and human welfare considerations, such as poverty and health, have long benefited from well-established quantitative frameworks for policy analysis and decision-making (environmental footprints, disability-adjusted life years4), animal welfare assessment has historically lacked comparable tools. Still, the effective allocation of limited resources to improve animal welfare depends on the ability to compare the impact of different policies and practices with a common metric, so prioritisation of the most cost-effective improvements may be possible. For example, producers comparing potential practice improvements, advocates selecting campaign priorities and policymakers designing regulations all require quantitative measures to determine which interventions yield the greatest welfare benefits relative to their costs. Scientifically substantiated quantification of animal welfare using a comparable metric is also a prerequisite to properly value financial incentives connected to welfare standards, and objectively assess trade-offs between animal welfare, economic and environmental policies.

A recent approach, the Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF)5,6,7,8, addresses this need by providing a scientifically rigorous methodology for quantifying diverse animal welfare impacts through a standardized measure: the cumulative time animals spend in affective states of varying intensities. Similar to life cycle analysis, the WFF begins by defining the scope of analysis, followed by an inventory of relevant circumstances (e.g., handling procedures, housing, density, air/water quality) and their biological outcomes (e.g., injuries, diseases, deprivations) over a timeframe of interest. The impact of these biological outcomes on welfare is evaluated by estimating the intensity and duration of each resulting affective experience (e.g., physical pain, fear, or joy), using existing evidence from multiple research lines. By quantifying the total time animals spend in negative and positive affective states of different intensities (termed ‘Cumulative Pain’ and ‘Cumulative Pleasure’), the WFF provides a comparable and relatable metric that is applicable across scenarios and species5,6,9,10,11.

In this study, we apply the WFF to quantify a pervasive source of vertebrate suffering: the slaughter of fish. The welfare of fish at the time of killing is currently at the center of policy discussions in multiple jurisdictions12. With an estimated 1.1–2.2 trillion wild finfishes13 and 78–171 billion farmed finfish14 killed annually, the scale of potential welfare improvements is substantial. However, decision-making is hampered by the lack of standardized metrics for evaluating the welfare impacts of different stunning and slaughter methods on a common scale. This study addresses this gap by quantifying the welfare impact of asphyxia in air—a prevalent slaughter method in fisheries and aquaculture at a global scale15.

We use the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) as a case study, given its global importance in aquaculture and the existing research base on its neurophysiology and welfare. Our findings provide the first quantitative estimates of pain during fish slaughter, demonstrating the potential scale of welfare improvements achievable through effective stunning methods.

Welfare impact assessment: the welfare footprint framework

Animal welfare footprints quantify the impacts of practices, policies or conditions on animal welfare. The WFF expresses these impacts through a fundamental metric that connects directly to animal experience: time spent in different affective states. By measuring welfare in units of time—such as hours of pain or pleasure at varying intensities, the framework provides a concrete, relatable scale for comparing welfare impacts across scenarios. Here, the terms ‘pain’ and ‘pleasure’ are used as shorthand for negative and positive affect, respectively8,16.

The WFF uses a structured assessment approach8: first, it establishes analytical boundaries, such as the geographies, production systems, breeds, life stages and the circumstances of interest (e.g., housing conditions, stocking density, handling procedures). Here, analytical boundaries are limited to analyzing the impact of air exposure for the slaughter of rainbow trout. The assessment spans from the moment of emersion to loss of consciousness. Exposure to ice or ice slurry, handling or pre-slaughter practices to which fish are exposed are beyond the scope of this study, with these other practices varying substantially depending on the species and commercial conditions. This focused scope enables establishing a baseline understanding of a welfare impact (asphyxia in air) that is still widespread in both fisheries and aquaculture, while acknowledging that total welfare impact during slaughter will be greater when considering these additional circumstances.

A second step involves identifying the biological outcomes of the circumstances of interest. For air exposure during slaughter, the primary biological outcome is asphyxiation. Next, the welfare impact of the affective experiences arising from each outcome (here, the pain and distress associated with asphyxia) is assessed by estimating both how long the experience lasts and how intense it is7.

The subjective assessment of indirect evidence is inherent to all animal welfare assessments. Behavioural indicators (e.g., vocalizations, posture, activity), neurophysiological measures, and responses to pain-relieving drugs are widely used to infer the presence and severity of affective states, often through expert judgment. For example, the European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) risk assessment model relies on literature reviews and expert elicitation to assign intensity scores to welfare consequences based on their perceived pain and distress17. In the Welfare Quality® Protocol18, experts estimate the severity of different issues on a 0 to 100 scale, then aggregated into composite scores. In the Five Domains Model19, experts grade welfare compromises on a scale (A to E) based on their evaluation of indirect indicators. In the WFF, the subjectivity inherent to this process is constrained in several ways, through a process that ensures explicit and documented disclosure of evidence-to-judgment pathways. First, it breaks each experience into meaningful time segments, recognizing that intensity typically changes over time (e.g., sharp pain might dull during healing). Segmenting time allows for more precise matching of existing evidence to each phase of the experience. Second, the framework guides assessment by defining specific criteria for each intensity category (Table 1). For example, more intense pain sensations should be more disruptive, engaging more attention20,21 and requiring stronger doses of pain-relieving drugs. Each piece of evidence is then evaluated for its consistency with these criteria (see Supplementary Information). For example, evidence that a pain experience requires high doses of strong analgesics for relief would be rated as consistent only with higher intensity categories. This structured and explicit evaluation process ensures transparency and constrains subjectivity by rooting estimates in documented evidence rather than relying solely on expert opinion. Third, the WFF acknowledges uncertainty and natural variation in how animals experience conditions—some animals may feel pain more intensely or take longer to recover. Thus, rather than assigning a single, fixed intensity or severity category to a welfare challenge as in other welfare assessment models (e.g., 0–1017, A–E19, 0–10018, 0–122), the framework uses probabilities. For instance, if evidence is insufficient to differentiate between two intensity categories (e.g., Hurtful and Disabling), a 50% probability is assigned to each. Likewise, uncertainty ranges are used for duration estimates. Finally, through a notation system known as Pain-Track7 (or Pleasure-Track16 for positive experiences), estimates are made explicit to allow for review, criticism, sensitivity analysis and update as new evidence emerges.

Cumulative Pain or Pleasure are calculated by multiplying, for each cell in the Pain- or Pleasure-Track table, probabilities by its segment’s duration and summing the results across segments within each intensity (see Fig. 1). Since time estimates can be meaningfully combined, it is possible to estimate cumulative time in pain or pleasure in any period (e.g., a day, a lifetime) due to all experiences endured. For populations, impacts are estimated by considering the prevalence of each experience—for instance, if a disease causing 10 days of pain affects 30% of animals, this represents 3 days of pain for the average population member. Additionally, time spent in different intensities can be also meaningfully combined into a single scale when needed. For instance, minutes or hours in Hurtful, Disabling, and Excruciating pain can be added together to report total time in 'moderate to intense pain’, while maintaining the granular, disaggregated data for detailed analysis.

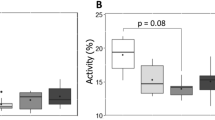

(A) Pain-track with hypotheses on how pain (negative affect) intensity changes over time when trout are removed from water until loss of consciousness. The vertical axis shows pain intensities defined in Table 1 (where ‘pain’ is a shorthand for ‘any negative affective experience’). For each segment (I–IV), estimated probability that the fish experiences each intensity can be traced back to the evidence reviewed (behavioral, neurophysiological, pharmacological indicators in Table 2 (see also Table S1). Total time to unconsciousness is estimated to range from 2 to 25 min, varying with fish size and water temperature, based on studies measuring loss of visual evoked response and vestibulo-ocular reflex. Segment IV is estimated to occupy 5–20% of total time based on EEG measurements of declining brain activity. (B) Cumulative Pain table showing time in pain (negative affect) at each intensity (obtained by multiplying the probability of each pain intensity by the duration of each segment, which is then summed across all intensities). Since Segments I-III have identical probabilities, they are analyzed as one time period for Cumulative Pain calculation.

Though individual-level and population-average estimates are crucial for understanding welfare, impacts can also be expressed per kilogram of production. This dual reporting serves several purposes. First, it allows meaningful comparison between production systems with different efficiency—for example, extensive systems may have better individual welfare but require more animals to produce the same output, meaning more total suffering could occur despite better conditions for each animal. Second, it enables cost-effectiveness analysis such as those needed for policy decisions that must balance welfare improvements with economic considerations of costs per production output. Third, production-standardized metrics also empower consumers, who typically purchase animal products by weight, to understand and compare the welfare impact of their purchases. They complement rather than replace individual welfare assessment—while efficiency matters for comparing systems, the moral significance of individual suffering remains unchanged regardless of their productive output.

Evidence review: temporal evolution of asphyxia-induced stress

The following analysis presumes the sentience of fish and their capacity for pain and distress, as supported by a robust body of evidence (reviewed in Sneddon 202023). We review existing evidence on the temporal evolution of the stress responses triggered upon emersion, categorised into the following time segments: 1. Initial air exposure, 2. pH imbalance and hypercapnia, 3. metabolic exhaustion, and 4. depressed neuronal activity. The evidence reviewed is also summarised in Table 2.

Segment I: Initial air exposure

Air exposure is one of the greatest stressors for fishes, used as a reliable stress-inducing procedure in research24,25,26. As little as 60 s of air exposure has been shown to elicit a physiological stress response consistently greater than that triggered by longer-lasting stressors27. Notably, air exposure is the only stressor capable of causing hydromineral disturbance within such a short time frame28. Other stressors (e.g. hypoxia, crowding, handling) require longer exposure to elicit comparable responses27,29.

When fishes are removed from water, their gill filaments adhere and gill lamellae collapse, preventing oxygen uptake and CO2 excretion24,26. The acute stress from oxygen deprivation triggers a set of hormonal responses30 that suppress non-essential processes31,32,33. Under normal conditions, there would be an increase in energy substrates and oxygen to the muscles and cardiorespiratory system to regain homeostasis33,34, but this mechanism is compromised out of water and energy reserves are quickly depleted. Intense physical activity prior to emersion exacerbates the physiological effects of asphyxia24, quickly exceeding stress coping ability24,35. Indeed, there is substantial suppression of coping mechanisms in the brains of trout exposed to asphyxiation, with impaired expression of stress-related proteins36.

While physiological stress can be an adaptive response, air exposure is highly aversive and detrimental to most fish species. As soon as individuals are out of water, intensive aversive reactions and movements are observed37,38. Even a few seconds of air exposure has been associated with the expression of neuromolecular states associated with negative emotions25, including higher expression of markers of neural activity in brain regions homologous to those involved in aversion processing in mammals39. Brief periods of air exposure also lead to persistent avoidance over time, even when only a cue (a conditioned place) of the experience is present40.

Evolutionarily, it is adaptive for the unpleasantness of air exposure to be very intense because even a few minutes of exposure poses a direct and severe threat to survival. This intense unpleasantness acts as a powerful aversive signal, driving immediate escape behaviors to return to water. Such rapid responses are crucial for minimizing the risk of suffocation and enhancing survival chances in natural environments where accidental stranding or low water levels may occur.

Segment II: Hypercapnia and pH imbalance

When metabolic CO2 in the blood increases (i.e. hypercapnia), additional disturbances are triggered. CO2 combines with water to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), which dissociates into bicarbonate (HCO3−) and protons (H+). Since the capacity of haemoglobin to buffer H+ is limited, blood pH is reduced (hypercapnic acidosis)41. Acidosis is further enhanced by the increased concentration of blood lactate, an acidic waste product of the anaerobic metabolism24.

Maintaining proper acid–base balance and arterial CO2 is critical for survival, so subtle changes in pH and CO2 trigger prompt responses to these threats. The excitability of neurons is especially sensitive to changes in pH41, increasing respiratory drive to remove excess CO2 and protect against acidosis41,42. However, this compensatory adjustment is impaired in the air as gas exchange is inhibited. In fish, CO2 is readily detected even at very low concentrations43. CO2-sensitive receptors that respond to other noxious chemicals have been identified, supporting the notion that hypercapnia stimulates the nociceptive system and is painful44,45. Symbolic of CO2 aversiveness is its use as a non-physical barrier for fish46 and mechanism of self-transfer between tanks47. Importantly, research has shown that CO2 induced behavioural effects on larval fish can be reduced using analgesics48.

Exposure to higher levels of CO2 also triggers a feeling of severe breathlessness, an increasingly distressing urge to breathe49. Accordingly, vigorous behavioural reactions, escape attempts and gasping are observed soon following exposure to higher CO2 concentrations50. Evidence is also robust that acid–base imbalances lead to anxiety and panic. In fish, hypercapnia triggers the release of catecholamines proportionally to the severity of the acidosis51,52 and strong catecholamine stimuli are known to induce panic attacks in humans53. Moreover, CO2-induced aquatic acidification reduces the action potential of GABA receptors, an inhibitory neurotransmitter that controls nerve cell hyperactivity due to anxiety, stress and fear54. This GABAA receptor dysfunction has been directly linked to increased anxiety-like behaviors in rockfish, with behavioral changes reversed upon return to normal CO2 conditions, indicating the causative role of CO2 in inducing anxiety through GABAA receptor alterations54,55.

CO2 is among the most well-studied substances that induce anxiety and panic-like responses across vertebrates. In mammals, hypercapnic environments with only 7% CO2 trigger fear, anxiety, and panic49,56, with brain regions and neurotransmitters involved in negative emotional responses activated by hypercapnia and acidosis56. While direct evidence of anxiolytic relief of CO2-induced fear specifically in fish is limited, the demonstrated role of GABAA receptor dysfunction in both CO2-induced behavioral alterations and anxiety strongly suggests shared mechanisms across vertebrates54,55,57. Prior to loss of consciousness, exposure to higher CO2 concentrations in other groups has been shown to activate neural pathways that elicit anxiety and fear50,58. In humans, the unpleasantness of CO2 inhalation increases with CO2 concentration59. Low pH also affects hemoglobin’s affinity to O2, further reducing O2 saturation. The resulting unpleasantness is thus likely to shift towards panic due to the escalating hypercapnia60.

Segment III: Metabolic exhaustion

The vigour, frequency and duration of muscular activity is progressively reduced some time after removal from water37,61. Several authors suggest that the time it takes for fish to be completely still is most likely modulated by metabolic exhaustion rather than insensibility37,62. The time until metabolic exhaustion can vary greatly between and within species63, as metabolic rate is modulated by several factors, including body mass, energy reserves, anaerobic scope and temperature64.

When oxygen is lacking, a switch to anaerobic metabolism occurs, which is less efficient at generating ATP and leads to the rapid depletion of glycogen and accumulation of lactate, further reducing pH. As pH becomes more acidic, acid-sensing ion channels in neurons are activated. This can lead to depolarization of neurons, which might manifest as heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli, including pain. Additionally, metabolic acidosis may also trigger specific pain receptors65. As lactate continues to accumulate, it inhibits key enzymes involved in energy production, further limiting the ability to maintain high-intensity efforts.

Besides exhaustion, individuals are still exposed to hypercapnia and acidosis. They may also experience ischemic pain (due to insufficient oxygen supply to tissues) and pain from high levels of lactate66. Ischemia can also trigger the release of inflammatory mediators, increasing pain67.

Segment IV: Depressed neuronal activity

In addition to acidifying the blood, CO2 also crosses the brain-blood barrier, causing cerebrospinal fluid acidification59. This ultimately results in unconsciousness, namely loss of the ability for subjective experiences68, inferred through visual and neurophysiological indicators (loss of equilibrium, opercular movements, response to external stimuli), and absence of the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and visually evoked responses (VER) to light, recorded by electroencephalogram (EEG). Acidification can increase the concentration of glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (a major inhibitory neurotransmitter69) and decrease that of glutamate (excitatory neurotransmitter)70,71. This process is likely gradual, with an increasingly greater level of neuronal necrosis until loss of consciousness36,72. Once consciousness is lost, movements can still occur, such as irregular muscle contractions, trembling of lower jaw and fins. These movements are likely due to local muscular activity rather than conscious responses37.

Results: Cumulative Pain from asphyxia in air

Based on the evidence reviewed in the previous section, we estimate the duration and intensity of pain likely experienced during asphyxia in air by analyzing the timing of the neurophysiological processes triggered upon air exposure and evaluating the probability of different pain intensities across Segments I through IV.

As reviewed, loss of consciousness is inferred through visual and neurophysiological indicators73,74 and absence of VOR and VER. In trout, some data suggest that VERs are lost together with breathing and eye-rolling reflexes75. However, other visual indicators such as breathing are not correlated with loss of VERs76,77 and are therefore poor indicators of unconsciousness. Studies show considerable variation in time to unconsciousness: in one study, VER was lost 2.2–3.0 min and 2.6–3.4 min after air exposure at 20 °C and 14 °C, respectively37, while in larger (~ 500 g) trout at 10 °C, loss of VOR took 17.6 ± 2 min for the 56% of trout that lost consciousness within the 20-min observation period (the remaining animals took longer than 20 min)36. Considering the variability of pre-slaughter conditions that affect time to unconsciousness (differences in slaughter weight, air temperature), we assume a conservative, wide interval of probable durations, from 2 to 25 min. Based on EEG observations of declining brain signal amplitude of trout exposed to air37, depression of neuronal activity (segment IV) occupies the final 5–20% of this total time, thus lasting 0.1 to 5 min (Fig. 1A). The remaining 80–95% (1.9 to 20 min) corresponds to Segments I through III. Since these segments share identical probability distributions for pain intensity (Fig. 1A), they can be analyzed as a single time period.

The probability of each pain intensity category is estimated through systematic evaluation of the evidence, summarized in Table 2, with each piece of evidence rated for its consistency with the intensity criteria defined in Table 1. For example, the observation of 'intensive aversive reactions, including vigorous movements of twisting and turning and escape attempts’ upon removal from water indicates a maximal emergency response that is consistent ( +) with both Disabling and Excruciating pain categories. Still, the possibility of Hurtful pain cannot be completely ruled out, illustrating the importance of representing this uncertainty in the analysis rather than forcing assignment to a single intensity category. Detailed justifications for the rating of evidence are provided in Table S1.

This probabilistic approach explicitly acknowledges both uncertainty in assessment and natural variation in how different individuals perceive the experience. When evidence suggests equal consistency with multiple categories (as in Segments I through III, where findings align similarly with both Disabling and Excruciating pain), probabilities are divided equally between them rather than forcing an arbitrary choice of one category. When evidence tends to favor certain categories but cannot definitively rule out others, higher probabilities are assigned to the better-supported categories while maintaining non-zero probabilities for plausible alternatives. In Segments I through III, evidence in Table 2 is primarily consistent with Disabling and Excruciating pain, but Hurtful pain cannot be completely ruled out. Therefore, a lower (20%) likelihood is assigned to Hurtful pain, with the remaining 80% distributed equally between Disabling and Excruciating categories.

This approach differs from traditional assessment methods that assign intensity or severity of a welfare harm to a single category (e.g., 0–1017, A–E19, 0–10018, 0–122), representing complete certainty in this assignment. Use of probabilities is also particularly valuable for dynamic processes where intensity changes over time. Here, evidence for Segment IV indicates a reduction in pain intensity as individuals approach unconsciousness. Since the evidence reviewed does not enable distinguishing between Hurtful, Annoying, and No Pain during this period, each category is attributed an equal likelihood of 33%, reflecting this uncertainty. This distribution of probabilities can also be interpreted as representing the gradually reducing intensity of distress (from Hurtful to No Pain) as the cerebrospinal fluid is acidified and neuronal activity is inhibited. While the exact probability values are necessarily subjective (e.g., 20% vs 15% or 25%), this approach provides a more realistic representation of both uncertainty in assessment and the inherent variability in perception across individuals.

Cumulative Pain is calculated by multiplying, for each time segment in Fig. 1A, the probability of each pain intensity by that segment’s duration, then summing across all intensities. Converting the estimates in Fig. 1A into Cumulative Pain (Fig. 1B) results in a total of 10 (1.9–21.7) minutes of moderate to extreme pain (Hurtful, Disabling and Excruciating pain combined) per trout due to air asphyxia (Fig. 1), corresponding to 24 (3.5–74) minutes of intense (Disabling and Excruciating) pain per Kg, assuming a slaughter weight of 0.2–1.2 kg.

Discussion

Animal welfare valuation for decision-making in different areas requires comparable quantitative knowledge of welfare. We applied the Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) to quantify the welfare impact of air asphyxia, a widespread practice in fisheries and aquaculture. For rainbow trout, an estimated 10 (1.9–21.7) minutes of moderate to extreme pain (Hurtful, Disabling and Excruciating pain combined) are endured by each trout due to air asphyxia (Fig. 1). When standardized by production output, this corresponds to an average of 24 min per Kg, with over one hour of moderate to extreme pain per kg in some cases (3.5–74 min per Kg).

Pain and distress from asphyxia in fish can be potentially mitigated by stunning methods that induce rapid loss of consciousness. For stunning to be considered humane and effective, pre-slaughter handling must be minimised and the animal must become unconscious immediately after stunning, a state that must persist until death. Welfare-wise, electrical and percussive stunning could potentially meet the second criterion if properly implemented36,78,79. In the former case, assuming estimates of 6 cents per kg of trout (from 3.60 to 3.66 € per kg—a 3% cost increase in ex-farm price80) and 70–100% stunning effectiveness36,75, this would represent approximately 60–1200 min (1–20 h) of moderate to extreme pain averted per dollar invested.

However, recent evidence has challenged assumptions of stunning effectiveness in commercial settings. EEG studies across multiple species have shown that electrical stunning often produces variable or insufficient stunning duration76,77,81,82, mis-stunning or electro-immobilization without loss of consciousness76. Percussion stunning, while effective when correctly positioned77,81,82, still faces multiple implementation challenges in commercial settings, including precise positioning and strength requirements, the need for equipment calibrated to different fish sizes and worker fatigue. In all cases, equipment failures are also an obstacle. Consequently, the theoretical welfare benefits of stunning can only be realized with continued development of stunning technologies, implementation protocols and training, and appropriate oversight to ensure consistent effectiveness across conditions.

Several factors also suggest asphyxia in ice or chilling in ice slurry are not humane alternatives to stunning in trout, and would lead to an even greater burden of pain as that estimated here. As a cold-water species adapted to temperatures as low as 4 °C, rainbow trout are unlikely to experience rapid unconsciousness from cold exposure alone. Rather, these methods may introduce additional challenges: direct tissue damage from ice crystal formation, thermal shock from abrupt temperature changes and physical pressure from ice. Moreover, by slowing down metabolic processes, lower temperatures may extend the time to unconsciousness, as already demonstrated in species such as seabass and seabream 83.

The welfare impact and effectiveness of any stunning method also depends critically on the entire harvest process, being affected by cumulative pre-slaughter stressors. Additionally, pre-slaughter practices (e.g., crowding, pumping, transport) are likely to represent a greater burden of pain than that estimated here, as they expose fish to multiple concurrent welfare challenges (e.g., poor water quality, crowding stress, physical exhaustion, pressure changes, mechanical trauma, temperature fluctuations) for much longer periods, from hours to days84,85. The WFF can also be used for assessing the welfare impacts of these processes and identifying priority areas for effective intervention.

While slaughter makes up a small fraction of the life of fish (typically of 8 to 24 months to market size in the case of trout), with reforms at the farm level being more impactful, the tractability of slaughter interventions, their relevance to the scale of both aquaculture and fisheries (affecting billions of animals as a key human intervention point), and the potential for welfare improvements make this phase critical. Estimates of Cumulative Pain from asphyxia provides concrete metrics for informing current policy discussions around welfare policies and industry practices at the time of killing. The finding that 70–100% effective stunning could potentially avert 1 to 20 h of moderate to extreme pain per US dollar in capital costs provides producers and regulators with clear economic context for comparing welfare investments with the best benefit–cost ratio. For certification programs, these metrics enable setting evidence-based thresholds and comparing production practices. Importantly, quantitative metrics allow for clear communication of welfare impacts to both policymakers and consumers, with a measure that reflects an intrinsic aspect of animal experience (time in negative affective states).

Beyond trout, this analysis provides a foundation for understanding slaughter impacts across other commercially important aquatic species. While time to unconsciousness varies based on factors such as species-specific temperature adaptations, body size, metabolic rate, and pre-slaughter conditions, the fundamental physiological mechanisms of asphyxia-induced stress are highly conserved across vertebrates. This means the processes described and progression through acute stress, hypercapnia, metabolic exhaustion, and eventual loss of consciousness likely follow similar patterns, providing a baseline for estimating the welfare impacts of air exposure in other species. Applying this baseline effectively to other aquaculture species, however, depends on species-specific data for estimating the duration and intensity of these processes, as well as an understanding of each species’ responses to asphyxia. Notably, species adapted to hypoxic environments are likely to show different responses than rainbow trout, a high oxygen-demand species. A key limitation at present is the relative scarcity of behavioral and neurophysiological research to inform the parameters estimated here, including measurements of time to unconsciousness, across a diverse range of commercially important aquatic organisms.

Naturally, estimates of Cumulative Pain are only as accurate as current knowledge allows. This limitation is inherent to any method. However, the WFF makes the process transparent by detailing how existing evidence supports each intensity at each time segment. This transparency highlights existing knowledge gaps and allows for the incorporation of new evidence as data become available.

In summary, the WFF enabled quantifying the pain associated with the most common method of fish slaughter, one that affects billions of animals annually. These findings have immediate relevance for shaping slaughter standards and can inform decisions that must balance animal welfare, economic and environmental considerations. Ultimately, this approach may facilitate more evidenced-informed collaboration across disciplines, paramount to improve the lives of animals on a large scale.

Data availability

All data for the analyses presented are made available in the main text and Supplementary Information file online.

References

Giménez-Candela, M., Saraiva, J. L. & Bauer, H. The legal protection of farmed fish in Europe: Analysing the range of EU legislation and the impact of international animal welfare standards for the fishes in European aquaculture. Derecho Anim. Forum Anim. Law Stud. 11, 0065–0118 (2020).

Keeling, L. et al. Animal welfare and the United Nations sustainable development goals. Front. Vet. Sci. 6, 336 (2019).

Broom, D. Farm animal welfare: A key component of the sustainability of farming systems. Vet. Glas. 75, 145–151 (2021).

Murray, C. J. Quantifying the burden of disease: The technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull. World Health Organ. 72, 429–445 (1994).

Alonso, W. J. & Schuck-Paim, C. Welfare Footprint Framework: methodological foundations and quantitative assessment guidelines. https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/94bxs (Center for Welfare Metrics, 2025).

Khire, I. & Ryba, R. Are slow-growing broiler chickens actually better for animal welfare? Shining light on a poultry welfare concern using a farm-scale economic model. Br. Poult. Sci. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668.2024.2432926 (2025).

Alonso, W. J. & Schuck-Paim, C. Pain-track: A time-series approach for the description and analysis of the burden of pain. BMC Res. Notes 14, 229 (2021).

Alonso, W. J. & Schuck-Paim, C. Comparative measurement of welfare in animals: the Cumulative Pain framework. In Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens: A Blueprint for the Comparative Analysis of Welfare in Animals (eds Schuck-Paim, C. & Alonso, W. J.) https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/cmyur (Center for Welfare Metrics, 2021).

Schuck-Paim, C & Alonso, WJ. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens. A Blueprint for the Comparative Analysis of Welfare in Animals. (Center for Welfare Metrics, 2021). https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/cmyur

Schuck-Paim, C. & Alonso, W. J. Quantifying Pain in Broiler Chickens: Impact of the Better Chicken Commitment and Adoption of Slower-Growing Breeds on Broiler Welfare. (Center for Welfare Metrics, 2022). https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/n6we4

McKay, H. & McAuliffe, W. Quantifying and Prioritizing Shrimp Welfare Threats. (Rethink Priorities, 2024) https://10.17605/osf.io/4qr8k.

Pavlidis, M., et al., F. Research for PECH Committee—Animal welfare of farmed fish, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/ipol_stu(2023)747257 (2023).

Mood, A. & Brooke, P. Estimating global numbers of fishes caught from the wild annually from 2000 to 2019. Anim. Welf. 33, e6 (2024).

Mood, A., Lara, E., Boyland, N. K. & Brooke, P. Estimating global numbers of farmed fishes killed for food annually from 1990 to 2019. Anim. Welf. 32, e12 (2023).

European Food Safety Authority. Species-specific welfare aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing of farmed fish: Rainbow trout. EFSA J. 1013, 4–55 (2009).

Alonso, W. J. & Schuck-Paim, C. Beyond suffering: A framework for quantifying positive animal welfare in individuals and populations. (Center for Welfare Metrics, 2024). https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/mdgjr

EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW). Guidance on risk assessment for animal welfare. EFSA J. 10, 2513 (2012).

Welfare Quality Consortium. Welfare Quality Assessment Protocol for Pigs (sows and Piglets, Growing and Finishing Pigs). http://www.welfarequalitynetwork.net/media/1018/pig_protocol.pdf (2009).

Mellor, D. J. Operational details of the five domains model and its key applications to the assessment and management of animal welfare. Animals 7, 60 (2017).

Barclay, R. J., Herbert, W. J. & Poole, T. The Disturbance Index: A Behavioural Method of Assessing the Severity of Common Laboratory Procedures on Rodents (Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, 1988).

Eccleston, C. & Crombez, G. Pain demands attention: A cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychol. Bull. 125, 356–366 (1999).

Teng, K.T.-Y. et al. Welfare-adjusted life years (WALY): A novel metric of animal welfare that combines the impacts of impaired welfare and abbreviated lifespan. PLoS ONE 13, e0202580 (2018).

Sneddon, L. U. Can fish experience pain? In The Welfare of Fish (eds Kristiansen, T. S. et al.) 229–249 (Springer, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41675-1_10.

Ferguson, R. A. & Tufts, L. Effects of brief air exposure in exhaustively exercised rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss: Implications for ‘catch and release’ fisheries. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 49, 1–6 (1992).

Cerqueira, M. et al. Cognitive appraisal of environmental stimuli induces emotion-like states in fish. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Cook, K. V., Lennox, R. J., Hinch, S. G. & Cooke, S. J. FISH out of WATER: How much air is too much?. Fisheries 40, 452–461 (2015).

Trushenski, J., Schwarz, M., Takeuchi, R., Delbos, B. & Sampaio, L. A. Physiological responses of cobia Rachycentron canadum following exposure to low water and air exposure stress challenges. Aquaculture 307, 173–177 (2010).

Hur, J. W., Kang, K. H. & Kang, Y. J. Effects of acute air exposure on the hematological characteristics and physiological stress response of olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and Japanese croaker (Nibea japonica). Aquaculture 502, 142–147 (2019).

Arends, R. J., Mancera, J. M., Muñoz, J. L., Wendelaar Bonga, S. E. & Flik, G. The stress response of the gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) to air exposure and confinement. J. Endocrinol. 163, 149–157 (1999).

Henry, J. P. Biological basis of the stress response. Integr. Physiol. Behav. Sci. 27, 66–83 (1992).

Barton, B. A. Stress in fishes: A diversity of responses with particular reference to changes in circulating corticosteroids. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 517–525 (2002).

Cook, K. V. Molecular, Physiological and Behavioural Responses to Capture in Pacific Salmon Commercial Fisheries: Implications for Post-release Survival of Non-target Salmon Species (University of British Columbia, 2018). https://doi.org/10.14288/1.0374207.

Wendelaar Bonga, S. E. The stress response in fish. Physiol. Rev. 77, 591–625 (1997).

Wang, Q. et al. The effect of air exposure and re-water on gill microstructure and molecular regulation of Pacific white shrimp Penaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 132, 108458 (2023).

Barton, B. A., Schreck, C. B. & Sigismondi, L. A. Multiple acute disturbances evoke cumulative physiological stress responses in juvenile Chinook salmon. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 115, 245–251 (1986).

Saraiva, J. L. et al. Welfare of rainbow trout at slaughter: Integrating behavioural, physiological, proteomic and quality indicators and testing a novel fast-chill stunning method. Aquaculture 581, 740443 (2024).

Kestin, S. C., Wotton, S. B. & Gregory, N. G. Effect of slaughter by removal from water on visual evoked activity in the brain and reflex movement of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Vet. Rec. 128, 443–446 (1991).

Brydges, N. M., Boulcott, P., Ellis, T. & Braithwaite, V. A. Quantifying stress responses induced by different handling methods in three species of fish. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 116, 295–301 (2009).

O’Connell, L. A. & Hofmann, H. A. The vertebrate mesolimbic reward system and social behavior network: A comparative synthesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 519, 3599–3639 (2011).

Millot, S., Cerqueira, M., Castanheira, M. F. & Øverli, Ø. Use of conditioned place preference/avoidance tests to assess affective states in fish. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 154, 104–111 (2014).

Ruffin, V. A., Salameh, A. I., Boron, W. F. & Parker, M. D. Intracellular pH regulation by acid-base transporters in mammalian neurons. Front. Physiol. 5, 43 (2014).

Putnam, R. W., Filosa, J. A. & Ritucci, N. A. Cellular mechanisms involved in CO2 and acid signaling in chemosensitive neurons. Am. J. Cell Physiol. 287, 1493–1526 (2004).

Perry, S. F. & McKendry, J. E. The relative roles of external and internal CO2 versus H(+) in eliciting the cardiorespiratory responses of Salmo salar and Squalus acanthias to hypercarbia. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 3963–3971 (2001).

Mettam, J. J., McCrohan, C. R. & Sneddon, L. U. Characterisation of chemosensory trigeminal receptors in the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss: Responses to chemical irritants and carbon dioxide. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 685–693 (2012).

Sneddon, L. U. Evolution of nociception and pain: evidence from fish models. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 374, 20190290 (2019).

Schneider, E. V. C., Hasler, C. T. & Suski, C. D. Fish behavior in elevated CO2: Implications for a movement barrier in flowing water. Biol. Invasions 20, 1899–1911 (2018).

Clingerman, J., Bebak, J., Mazik, P. M. & Summerfelt, S. T. Use of avoidance response by rainbow trout to carbon dioxide for fish self-transfer between tanks. Aquacult. Eng. 37, 234–251 (2007).

Lopez-Luna, J., Canty, M. N., Al-Jubouri, Q., Al-Nuaimy, W. & Sneddon, L. U. Behavioural responses of fish larvae modulated by analgesic drugs after a stress exposure. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 195, 115–120 (2017).

Banzett, R. B., Lansing, R. W. & Binks, A. P. Air hunger: A primal sensation and a primary element of dyspnea. Compr. Physiol. 11, 1449–1483 (2021).

Grandin, T. (ed.) The Slaughter of Farmed Animals: Practical Ways of Enhancing Animal Welfare. (CABI, 2020).

Perry, S. F., Kinkead, R., Gallatlgher, P. & Randall, D. J. Evidence that hypoxemia promotes catecholamine release during hypercapnic acidosis in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Respir. Physiol. 77, 351–364 (1989).

Wood, C. Acid-base and ion balance, metabolism, and their interactions, after exhaustive exercise in fish. J. Exp. Biol. 160, 285–308 (1991).

Sikter, A., Frecska, E., Braun, I. M., Gonda, X. & Rihmer, Z. The role of hyperventilation-hypocapnia in the pathomechanism of panic disorder. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 29, 375–379 (2007).

Hamilton, T. J., Holcombe, A. & Tresguerres, M. CO2-induced ocean acidification increases anxiety in rockfish via alteration of GABAA receptor functioning. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281, 20132509 (2014).

Nilsson, G. E. et al. Near-future carbon dioxide levels alter fish behaviour by interfering with neurotransmitter function. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 201–204 (2012).

Améndola, L. & Weary, D. M. Understanding rat emotional responses to CO2. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 253 (2020).

Regan, M. D. et al. Ambient CO2, fish behaviour and altered GABAergic neurotransmission: Exploring the mechanism of CO2-altered behaviour by taking a hypercapnia dweller down to low CO2 levels. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 109–118 (2016).

Steiner, A. R. et al. Humanely ending the life of animals: Research priorities to identify alternatives to carbon dioxide. Animals 9, 911 (2019).

Terlouw, C., Bourguet, C. & Deiss, V. Consciousness, unconsciousness and death in the context of slaughter. Part I. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying stunning and killing. Meat Sci. 118, 133–146 (2016).

Hawkins, P. et al. A Good death? Report of the second Newcastle meeting on laboratory animal euthanasia. Animals 6, 50 (2016).

Poli, B. M., Parisi, G., Scappini, F. & Zampacavallo, G. Fish welfare and quality as affected by pre-slaughter and slaughter management. Aquac. Int. 13, 29–49 (2005).

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Species‐specific welfare aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing of farmed Atlantic Salmon. EFSA J. 7, 1011 (2009).

Killen, S. S. et al. Ecological influences and morphological correlates of resting and maximal metabolic rates across teleost fish species. Am. Nat. 187, 592–606 (2016).

Clarke, A. & Johnston, N. M. Scaling of metabolic rate with body mass and temperature in teleosts. J. Anim. Ecol. 68, 893–905 (1999).

de la Roche, J. et al. Lactate is a potent inhibitor of the capsaicin receptor TRPV1. Sci. Rep. 6, 36740 (2016).

Gregory, N. G. Physiology and Behaviour of Animal Suffering (Wiley, 2008).

Amantea, D., Nappi, G., Bernardi, G., Bagetta, G. & Corasaniti, M. T. Post-ischemic brain damage: Pathophysiology and role of inflammatory mediators. FEBS J. 276, 13–26 (2009).

Birch, J., Schnell, A. K. & Clayton, N. S. Dimensions of animal consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 789–801 (2020).

Schunter, C., Ravasi, T., Munday, P. L. & Nilsson, G. E. Neural effects of elevated CO2 in fish may be amplified by a vicious cycle. Conserv. Physiol. 7, 100 (2019).

Ang, R. C., Hoop, B. & Kazemi, H. Role of glutamate as the central neurotransmitter in the hypoxic ventilatory response. J. Appl. Physiol. 72, 1480–1487 (1992).

Ang, R. C., Hoop, B. & Kazemi, H. Brain glutamate metabolism during metabolic alkalosis and acidosis. J. Appl. Physiol. 73, 2552–2558 (1992).

Bowman, J., Nuland, N., Hjelmstedt, P., Berg, C. & Gräns, A. Evaluation of the reliability of indicators of consciousness during CO2 stunning of rainbow trout and the effects of temperature. Aquac. Res. 51, 5194–5202 (2020).

Sneddon, L. U. Clinical anesthesia and analgesia in fish. J. Exotic Pet Med. 21, 32–43 (2012).

Kestin, S. C., van deVis, J. W. & Robb, D. H. F. Protocol for assessing brain function in fish and the effectiveness of methods used to stun and kill them. Vet. Rec. 150, 302–307 (2002).

Jung-Schroers, V. et al. Is humane slaughtering of rainbow trout achieved in conventional production chains in Germany? Results of a pilot field and laboratory study. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 197 (2020).

Hjelmstedt, P. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of percussive and electrical stunning in rainbow trout: Does an epileptic-like seizure imply brain failure?. Aquaculture 552, 738012 (2022).

Brijs, J. et al. Effects of electrical and percussive stunning on neural, ventilatory and cardiac responses of rainbow trout. Aquaculture 594, 741387 (2025).

Robb, D. H. F., O’ Callaghan, M., Lines, J. A. & Kestin, S. C. Electrical stunning of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Factors that affect stun duration. Aquaculture 205, 359–371 (2002).

Lines, J. A., Robb, D. H., Kestin, S. C., Crook, S. C. & Benson, T. Electric stunning: A humane slaughter method for trout. Aquacult. Eng. 28, 141–154 (2003).

Springlea, R. Economic evaluation of humane slaughter methods for farmed fish in Italy. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/news/new-report-reveals-minimal-cost-fish-welfare (2022).

Hjelmstedt, P., To, F., Allen, P. J. & Gräns, A. Assessment of brain function during stunning and killing of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Aquaculture 596, 741825 (2025).

Sundell, E., Brijs, J. & Gräns, A. The quest for a humane protocol for stunning and killing Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 593, 741317 (2024).

de la Rosa, I., Castro, P. L. & Ginés, R. Twenty years of research in seabass and seabream welfare during slaughter. Animals 11, 2164 (2021).

Sneddon, L. U., Braithwaite, V. A. & Gentle, M. J. Do fishes have nociceptors? Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270, 1115–1121 (2003).

Ojelade, O. C., George, F. O. A., Abdulraheem, I. & Akinde, A. O. Interactions between pre-harvest, post-harvest handling and welfare of fish for sustainability in the aquaculture sector. In Sustainability Sciences in Asia and Africa 525–541 (Springer, 2023).

Kates, D., Dennis, C., Noatch, M. R. & Suski, C. D. Responses of native and invasive fishes to carbon dioxide: Potential for a nonphysical barrier to fish dispersal. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 69, 1748–1759 (2012).

Johnson, P. L., Truitt, W. A., Fitz, S. D., Lowry, C. A. & Shekhar, A. Neural pathways underlying lactate-induced panic. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 2093–2107 (2008).

Acknowledgements

CSP and WJA broader research is supported by the Open Philanthropy Project, though it did not specifically request this project or have any say over methods or results. This study received Portuguese national funds from FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology through projects UIDB/04326/2020, UIDP/04326/2020 and LA/P/0101/2020. Marco Cerqueira acknowledges a FCT contract, Ref 2020.02937.CEECIND. LUS received grants from the Swedish Research Council (VR) 2022-01365 and Formas 2021-02262.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributions listed according to CRediT guidelines. C.SP.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology (WFF refinement), writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. W.J.A.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology (WFF conceptualization and development), writing—review & editing, P.A.P.: writing—review and editing, L.U.S.: writing—review and editing, J.L.S.: writing—review and editing, M.C.: writing—review and editing, C.C.: writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schuck-Paim, C., Alonso, W.J., Pereira, P.A. et al. Quantifying the welfare impact of air asphyxia in rainbow trout slaughter for policy and practice. Sci Rep 15, 19850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04272-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04272-1