Abstract

Liquefaction is a phenomenon that occurs when there is a loss of strength in wet and cohesionless soil due to higher pore water pressures, and as a result, the effective stress is reduced due to dynamic loading. A construction site should first investigate the site for liquefaction, and for analyzing liquefaction, the most accurate method should be selected, which provides the most accurate results. In this work, a detailed investigation is performed on the effectiveness of ensemble learning and deep learning (DL) models in assessing the liquefaction susceptibility of soil deposits from a large database consisting of cone penetration test (CPT) measurements and field liquefaction performance observations of historical earthquakes. The performance of the developed models is assessed via several comprehensive performance fitness error matrices (PFEMs), including precision, accuracy, recall, specificity, F1 score, MCC, BA, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and area under the curve (AUC). Accuracy and validation loss curves were also plotted for all the proposed models. PFEMs are calculated, and a comparative study is performed for all the proposed methods. The BI-LSTM model has the highest accuracy, with 0.9791 in training and 0.8889 in testing, indicating strong predictive ability and good generalizability. LSTM follows closely with training and testing accuracies of 0.9433 and 0.8750, respectively, offering consistent performance. XGBoost also performs well, achieving 0.9194 in training and 0.8750 in testing, reflecting its robustness in handling complex patterns. In contrast, RF displays a significant discrepancy between the training (0.9373) and testing (0.8681) accuracies. Overall, BI-LSTM emerges as the most reliable model for assessing liquefaction potential, with LSTM, XGBoost and the RF also proving effective. Each model can offer unique strengths, with BI-LSTM and LSTM excelling at learning sequential dependencies, whereas XGBoost and RF provide powerful and often interpretable results from structured tabular data. This study advances the development of robust tools for assessing liquefaction hazards, thereby enhancing strategies for seismic risk mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The destructive effects of structural failure during strong seismic events, compounded by the occurrence of soil liquefaction, present a significant and ongoing challenge that demands a sustainable and long-term solution. Soil liquefaction arises when soil loses its solidity and behaves like a liquid, a phenomenon caused by the accumulation of excess pore water pressure, leading to a substantial decrease in effective stress. This process compromises the stability of structures and infrastructure, highlighting the need for comprehensive mitigation strategies. This phenomenon typically affects loose to medium-density soil deposits, where the rapid application of seismic forces during an earthquake does not allow sufficient time for water to dissipate through soil pores. Consequently, the confined water exerts pressure that inhibits the intergranular contact between soil particles, leading to a decrease in shear strength and an overall weakening of the soil mass. Risk assessment of naturally occurring phenomena, such as soil liquefaction, is critical in evaluating potential damage to infrastructure, human life, and the environment. Numerous probabilistic and deterministic methods have been developed over recent decades to assess the soil liquefaction potential, incorporating comprehensive studies and field data. These methods aim to predict the likelihood and severity of liquefaction, guiding the design and implementation of mitigation strategies to increase the resilience of structures in seismically active regions. Thus, understanding and mitigating soil liquefaction remain essential aspects of geotechnical and earthquake engineering.

Initially, research on soil liquefaction focused primarily on sandy soils. However, recent observations following certain earthquakes have revealed that liquefaction phenomena can also occur in fine-grained soils. Liquefaction phenomena have been extensively studied both qualitatively and statistically. Assessing liquefaction risk has been a central focus in geotechnical earthquake engineering for many years, utilizing various analysis methods based on laboratory and field tests. Laboratory tests, such as dynamic simple shear tests, dynamic triaxial shear tests, dynamic torsional shear tests, and shake table tests, are essential for determining the liquefaction potential of soils under cyclic loads. These tests simulate the conditions that soils experience during seismic events, which can help engineers evaluate the likelihood of soil failure. Field tests complement laboratory analyses by providing real-world data, thus enabling a comprehensive understanding of soil behavior under earthquake-induced stresses. Specifically, a rational procedure was employed by Liam Finn et al.1 and Seed and Peacock2, who utilized a dynamic simple share test to assess the probability of liquefaction of saturated sand deposits liquefied during earthquakes. Several researchers subsequently performed laboratory experiments, such as dynamic triaxial and torsional shear tests, to assess the liquefaction potential of soil subjected to seismic events3,4,5. Together, these methods play crucial roles in developing strategies to mitigate liquefaction risk. Numerous researchers have attempted to identify potential solutions to various liquefaction problems.

Field-based analysis techniques are frequently used to evaluate liquefaction potential because it is difficult to collect undisturbed soil samples and adequately simulate field conditions in laboratory trials. Standard penetration test (SPT) and cone penetration test (CPT) are important field tests. These methods are advantageous because they more accurately capture in situ conditions and behaviors. During an earthquake, the increase in pore water pressure within the soil, driven by cyclic shear stresses or resulting cyclic shear deformations, directly influences the potential for liquefaction. Therefore, comparing the cyclic shear stresses experienced during an earthquake with the liquefaction resistance of the soil, as determined by these tests, is crucial for calculating a safety factor against liquefaction. The "simplified method," first proposed by Seed and Idriss6, is a foundational approach that uses this comparison to assess liquefaction risk. This method has been widely adopted in geotechnical engineering to estimate the likelihood of soil liquefaction during seismic events, thus assisting in the design of safer infrastructure in earthquake-prone areas. The stress-based approach for calculating the soil liquefaction potential, initially proposed by Seed and Idriss, has been refined and expanded over the years7,8. This approach involves a comparison of the cyclic resistance ratio (CRR) of the soil, which signifies its capacity to withstand liquefaction, with the cyclic stress ratio (CSR) induced by an earthquake. A safety factor against liquefaction is subsequently calculated on the basis of this comparison. A safety factor below one typically signifies that the soil is susceptible to liquefaction. This method is fundamental in geotechnical earthquake engineering for assessing and mitigating liquefaction risks in susceptible soils. Robertson and Campanella9 introduced another empirical method that uses the CPT value as a primary parameter. This method leverages the measured cone penetration resistance, a key indicator of soil properties, to assess various geotechnical characteristics. Olson10 collected a database of 172 level ground liquefaction and no liquefaction case histories where CPT results are available and provided simple empirical tools to evaluate liquefaction problems in level and sloping ground10. Juang et al.11 developed a neural network trained on a large database of field examples and a CPT based simplified empirical equation for the evaluation of CRRs. Idriss and Boulanger12 provided updated SPT and CPT liquefaction correlations and recommended their usage in real-world applications8.

The analysis of the mentioned literature shows that the bulk of current models for forecasting the likelihood of liquefaction are based on computing techniques. Consequently, it is necessary to create new models via machine learning (ML) methods. In various fields of geotechnical engineering, machine learning methods, including slope stability13,14,15, rock mechanics16,17,18, soil mechanics19,20,21, soil dynamics19,22,23, and soil stabilization24,25,26,27,28,29,30, have been successfully applied. Pal31 proposed classification models based on a support vector machine (SVM) utilizing postliquefaction case histories. Samui32 created an RVM model for liquefaction potential evaluation via a trustworthy CPT-based liquefaction case history dataset. Various geotechnical problems, including liquefaction problems, have been resolved via the proposed soft computing technique33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Kumar et al.43,44,45 proposed several machine learning models to assess the liquefaction behavior of soil under seismic conditions via SPT-based datasets. In the field of geotechnical engineering, the use of advanced regression and classification ML models has provided outstanding results in predicting liquefaction potential46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. Liu54 evaluated the influence of fine content on soil liquefaction resistance. Many other researchers have developed liquefaction potential maps for different cities to assess liquefaction hazards55,56,57. Various probabilistic and deterministic studies have also been performed to assess the liquefaction behavior of soil at different locations58,59,60. Jas and Dodagoudar61 proposed the explainable-based XGBoost-SHAP model to predict the liquefaction potential of soil. In their study, the authors reported that the proposed explanatory models had an accuracy of approximately 88.24% in assessing the liquefaction potential of soil.

Recently, deep learning (DL) and several ML algorithms have been successfully applied to various complex problems in the field of science engineering, including noise annoyance, building quality problems, axial capacity prediction for cold-formed steel channel sections, the compressive strength of metakaolin mortar, liquefaction prediction and unconfined compressive strength62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71. Despite the widespread adoption of machine learning (ML) techniques in liquefaction assessment, the application of DL remains relatively limited. Kumar et al.72 developed a DL model to evaluate liquefaction susceptibility via the CPT database, which demonstrated superior consistency compared with the emotional back propagation neural network (EmBP) model. Similarly, Zhang et al.73 proposed an optimized DNN for SPT and shear wave velocity (Vs)-based datasets, which achieved high predictive accuracy. Kumar et al.74 further compared multiple DL models for liquefaction potential prediction using SPT-based data, identifying the RNN as the most effective. Additionally, Ghani et al.75 employed DL and ensemble learning approaches, highlighting the superior predictive performance of long short-term memory (LSTM) networks across various soil types. Furthermore, while previous research has demonstrated the promise of DL in liquefaction prediction, gaps remain in terms of evaluating the comparative performance and limitations of different DL models. Our study fills this gap by identifying the most effective DL architecture and highlighting the specific strengths and weaknesses of each model under different data conditions. This approach not only enhances the predictive performance but also contributes to the development of more generalizable and interpretable DL frameworks for seismic hazard assessment.

This study aims to overcome the limitations of ensemble ML models in predicting liquefaction by investigating a wider array of DL architectures. Ensemble ML approaches typically necessitate extensive feature engineering and domain expertise to identify and extract pertinent features, a process that is time intensive and susceptible to human error. Moreover, ML models often struggle with complex, high-dimensional data and may fail to capture intricate patterns and nonlinear relationships effectively. In contrast, DL models can autonomously learn significant features from raw data through multiple layers of abstraction, thereby enhancing their efficacy in complex tasks such as soil liquefaction prediction. Additionally, DL architecture can leverage large datasets to enhance model performance, whereas ensemble ML models may encounter challenges such as overfitting or underfitting when confronted with extensive and intricate data. These advantages establish DL models as more resilient and scalable solutions for seismic hazard assessment.

While prior research has demonstrated the potential of DL in liquefaction assessment, it has focused primarily on specific architectures or limited datasets. This study contributes through a comprehensive investigation that assesses the performance of DL models, including long short-term memory (LSTM) and bidirectional long short-term memory (BI-LSTMs). We evaluate these models via a robust dataset encompassing diverse soil properties and seismic scenarios. This comparative analysis not only identifies the most effective DL architecture for liquefaction prediction but also elucidates the specific strengths and weaknesses of each model in capturing the complex relationships underlying soil liquefaction susceptibility. The literature review substantiates the successful application of these methods in analogous engineering contexts, thereby affirming their efficacy and suitability for the objectives of the current study. The specific contributions of the authors are as follows:

-

a)

To introduce several ML models, including ensemble and DL models (eXtreme gradient boosting, random forest, long short-term memory, and bidirectional long short-term memory), and assess their effectiveness in assessing the liquefaction susceptibility of soil.

-

b)

Using the GridsearchCV methodology for hyperparameter tuning for the proposed models enhances the prediction capability.

-

c)

Several performance fitness error matrices (PFEMs), including precision, accuracy, recall, specificity, the F1 score, the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), balanced accuracy (BA), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the area under the curve (AUC), were analyzed to assess the effectiveness of the proposed models.

-

d)

Feature importance analysis was performed to assess the most significant features affecting liquefaction susceptibility prediction on the basis of the CPT database, which offers insights for improving the predictive accuracy of the ML model.

Data collection

In this study, liquefaction susceptibility was assessed via a large dataset compiled on the basis of cone penetration test (CPT) liquefaction assessment parameters related to the prediction of liquefied or non-liquefied case histories. A total of 479 datasets, which were taken from various earthquake case histories from different places worldwide, were used to perform the study. The dataset collected for this study from the literature11 contains an actual historical earthquake case liquefaction dataset. Out of a total of 479 data cases, 336 are classified as liquefiable cases, and 143 are classified as non-liquefiable cases. The CPT-based field dataset includes eight parameters, such as the maximum horizontal ground acceleration (\({a}_{max}\)), tip resistance (\({q}_{c}\)), total vertical stress (\({\sigma }_{v}\)), effective vertical stress (\({\sigma {\prime}}_{v}\)), depth (D), magnitude moment (\({M}_{w}\)), fine content (\(FC\)), and friction ratio (\({R}_{f}\)). All the variables with actual liquefaction condition datasets are provided in Appendix 1.

Data statistics and graphical representation

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the parameters used in this study. This table provides a comprehensive overview of the dataset’s variables, D, FC, \({a}_{max}\), \({q}_{c}\), \({\sigma }_{v}\), \({\sigma {\prime}}_{v}\), \({M}_{w}\), \({R}_{f}\) and liquefaction. As per the data presented in Table 1, the values of skewness for all features that are positive and greater than 0.5 indicate that the tail on the right side of the distribution (higher values) is longer or fatter than that on the left side. This suggests that the data are skewed toward higher values, with a majority of the data points clustered around the lower end but with some higher values stretching out to the right. However, kurtosis measures the “tailedness” of a distribution or how heavy or light the tails are compared to a normal distribution. All the features obtained positive kurtosis values, indicating that the distribution has heavier tails and sharper peaks than a normal distribution does. The peak horizontal ground acceleration (\({a}_{max}\)) range varies from a maximum value of 0.84 to a minimum value of 0.08 for the data used in this study. The tip resistance has a maximum value of 30,397.5 kPa and a minimum value of 810.6 kPa for all the cases analyzed.

In addition to the statistical summary, Fig. 1a–h presents violin plots for each feature to visualize their distributions. Violin plots are useful graphical tools for visualizing the distribution of a dataset, especially when comparing the distributions of multiple input variables. In this study, a violin plot is used to merge features of both a box plot and a kernel density plot. This visualization technique illustrates the data distribution across various categories or groups, capturing key aspects such as central tendency and variability. The width of the plot at different points indicates the density and spread of the data, providing a clear depiction of the shape and variability of the distribution within each group. This allows for a comprehensive comparison of data distributions across different categories. Wide sections indicate many data points, whereas narrow sections suggest few data points. The violin plot is usually symmetrical about the center. Figure 1a shows that the depth variations at approximately 4 m and 5 m represent wider sections, indicating more data points. Figure 1b indicates that most of the data points \({a}_{max}\) lie in the range of 0.1–0.4. Figure 1c indicates that the \({q}_{c}\) values range from 0 to 10,000 kPa. Figure 1d shows that the FC has a wider range of approximately 0% to 40% for most of the data points. Similarly, \({M}_{w}\) and \({r}_{f}\) have wider portions of approximately 6–7.5 and 0–1.5, respectively, for most of the data points. We look for any asymmetry, which might indicate skewness in the distribution. The presented figure shows that all the variables have a symmetrical pattern about the centerline.

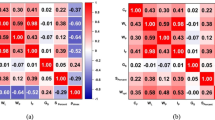

A pair plot, with subplots showing correlation coefficients, was used to illustrate the relationships between features in the dataset analysis. Figure 2 shows the pair plot, which consists of scatter plots for paired feature associations and kernel density estimate plots along the diagonal. The target variable, "liquefaction," is used to color-code these scatter plots, making it easier to distinguish between data points from different classes visually. Within the pair plot, there are subplots that display the linear correlations between feature pairs. The correlation coefficients, which can take on values between \({-}1\) and \(+ 1\), reveal the direction and intensity of these interactions. Relationships are considered linear when the coefficient is either \({-}1\) or \(+ 1\); when it is zero, no such relationship exists; and when it is one, the relationship is fully positive. This extensive correlation matrix study provides insight into the interrelationships of soil features, drawing attention to noteworthy correlations that contribute to our knowledge of feature interactions and how they may affect liquefaction. The research successfully captures and analyses the intricate interdependencies among the elements in the dataset via this visualization technique. The normal vertical stress and effective stress have very strong positive correlation coefficients of 0.99 and 0.93, respectively, indicating that they are highly dependent on each other. The fine content is highly correlated with \({R}_{f}\), with a correlation coefficient of nearly 0.07, and a significantly negative correlation with \({q}_{c}\), with a correlation value of \(-0.49\). However, the parameter \({a}_{max}\) has a poor correlation with all features, which means that the \({a}_{max}\) variable indicates that the relationships between other features are nonlinear. Finally, parameters \({M}_{w}\) and \({a}_{max}\) exhibit a weak negative correlation with \(-0.02\), suggesting a nonlinear relationship and a possible association between stronger earthquakes and slightly greater peak ground accelerations. Geologically, soils with higher fines contents generally exhibit reduced drainage capacity and increased compressibility, which in turn can lead to a decrease in penetration resistance during CPT. As fine particles such as silt and clay increase, the soil matrix becomes less dense and more resistant to shear strength mobilization under loading, resulting in lower measured \({q}_{c}\) values. This geotechnical behavior is consistent with the observed negative correlation and highlights the important role of soil texture and composition in influencing in situ test responses.

Methodology

Semiempirical procedure

A semiempirical field-based procedure is used in this analysis to analyze the liquefied and non-liquefied case histories. The advantage of this approach is that it uses theoretical ideas and experimental results to establish the foundation for the analysis methodology and its constituent parts. The cyclic stress ratio (\({CSR}_{7.5}\)) was adjusted to a standard earthquake magnitude of 7.5, which helps in comparing the liquefaction potential across different seismic events. Equation (1) is used to determine \({CSR}_{7.5}\) at a depth z below the surface of the ground, as proposed by Seed and Idriss6. By including a magnitude scaling factor (\(MSF\)), the equivalent number of stress cycles is also adjusted for earthquakes of various magnitudes.

The factor 0.65 is a constant used in the liquefaction potential evaluation, representing an empirical reduction factor on the basis of observations and studies of earthquake-induced soil liquefaction. To standardize the cyclic stress ratio \((CSR)\) induced by an earthquake of magnitude \(M\) to an equivalent \(CSR\) for an earthquake with a magnitude of \(M=7.5\), a magnitude scaling factor \((MSF)\) is applied. The \(MSF\) factor adjusts the CSR for different earthquake magnitudes, as different magnitudes result in different durations and numbers of loading cycles. The MSF typically reduces the CSR for larger magnitudes. MSF is used to account for the duration effects in triggering soil liquefaction, specifically considering the number and relative amplitudes of loading cycles. This factor adjusts for the influence of earthquake magnitude on the potential for liquefaction by addressing the cumulative damage effects associated with longer-duration shaking. In this study, the MSF values were calculated via the methodology proposed by Idriss and Boulanger76, which provides distinct MSF estimates for sandy and clayey soils. Their approach offers a nuanced assessment of liquefaction potential by incorporating soil type-specific characteristics and earthquake duration impacts, enhancing the accuracy of the liquefaction susceptibility evaluation, which is given by the following relationship presented in Eqs. (2) and (3):

However, the overburden correction factor was evaluated in terms of \({P}_{a}\) and \({\sigma {\prime}}_{vo}\) via the mathematical relationship presented in Eqs. (4) and (5).

It is necessary to use Eq. (4); however, this process can be simplified by selecting the automatic iteration option in an Excel spreadsheet. The number of qc1ncs was limited to 21–254 for Eq. (5). The shear stress reduction factor can be estimated via the parameters of the earthquake magnitude (M) and depth (z). The stress reduction coefficient is evaluated via the following empirical formula presented in Eqs. (6) to (8):

However, Boulanger77 established the basis for the \({K}_{\sigma }\) connection by demonstrating that the CRR for clean reconstituted sand in the laboratory may be related to the relative state parameter index of the sand. Idriss and Boulanger76 suggested representing the ensuing \({K}_{\sigma }\) connection in terms of \({q}_{c1Ncs}\), as presented in Eqs. (9) and (10).

By limiting \({q}_{c1Ncs}\) to \(\le\) 211, the coefficient \({C}_{\sigma }\) can be reduced to its maximum value of 0.3. The equivalent clean sand adjustments for the fine content present in the soil were also considered in this study. According to current CPT-based research, the liquefaction case histories reveal that when the fines content (\(FC\)) increases, the liquefaction-triggering correlations move to the left. The equivalent clean sand adjustments, \(\Delta {q}_{c1N}\), are empirically derived from the liquefaction case history data. The adjusted expression for equivalent clean sand in the CPT is as follows in Eq. (11):

where \(FC\) denotes the percentage of fine content.

Finally, fine content and soil classification estimation analyses were performed by estimating the CPT tip resistance and sleeve friction ratio. The CPT tip resistance and sleeve friction ratio are functions of the soil behavior type index (\({I}_{C}\)), which is a function of \(FC\) and soil categorization. Robertson and Wride78 suggested that the \({I}_{C}\) term be calculated via Eq. (12).

where Q and F are the normalized tip and sleeve friction ratios computed via Eqs. (13) and (14), respectively.

By first regressing \({I}_{C}\) against FC via the combined datasets to produce the least-squares fit, the connection for calculating \(FC\) was constructed via Eq. (15).

where \({C}_{FC}\) is a fitting parameter that can be modified depending on site-specific data.

The equation for the CPT-based data for calculating the cyclic resistance ratio (\(CRR\)) is as follows in Eq. (16).

where \({q}_{c1Ncs}\) is the equivalent clean sand adjustment given as follows in Eqs. (17) and (18).

where \({q}_{c1N}\) is the penetration resistance obtained from the same sand at an overburden stress of 1 atm when the other parameters remain constant.

Finally, the liquefaction safety factor is defined via Eq. (19).

Using Eq. (19), the factor of safety (FOS) against liquefaction was calculated for each dataset. A FOS less than 1 indicates that the soil is susceptible to liquefaction, suggesting a high risk of failure. Conversely, an FOS greater than 1 signifies that the soil is resistant to liquefaction, indicating stability under seismic conditions.

This study extends beyond conventional methodologies by exploring the potential of ensemble machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques for predicting liquefaction. These data-driven approaches enable the extraction of intricate patterns from extensive datasets comprising soil properties and seismic parameters, potentially increasing the precision and automation of predictions. Figure 3 illustrates the methodology flowchart adopted in this investigation. A diverse array of algorithms is scrutinized, encompassing ensemble ML models such as XGBoost and RF models. Furthermore, this research delves into the capabilities of deep neural networks (DNNs), including LSTM and Bi-LSTM networks, for capturing prolonged dependencies. The efficacy of these algorithms will undergo meticulous assessment via a comprehensive dataset incorporating soil properties and seismic data.

eXtreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)

XGBoost XGBoost stands out as an advanced gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) algorithm, which is an open-source library offering the application of ML algorithms for both regression and classification tasks in several fields79,80. The library is recognized for its efficiency, flexibility, and portability, supporting multiple programming languages such as C + + , Python, and R Studio. The XGBoost algorithm builds a sequence of classification or regression trees, known as CART, which serve as weak learners. These trees are sequentially combined to create the final prediction model. In line with other boosting techniques, XGBoost incrementally constructs regression trees, refines the model step-by-step and ensures that each tree minimizes the average loss function value across all steps in the training set. XGBoost enhances predictive accuracy by combining multiple weak learners, typically decision trees. Iteratively addressing previous prediction errors, each new model learns from residuals to improve overall accuracy. The inclusion of a regularization term in its objective function helps reduce overfitting and manage model complexity. The algorithm constructs a series of classification or regression trees (CARTs) step by step, and XGBoost minimizes the average loss function value at each step, forming a robust final predictive model.

Specifically, the model is trained on the dataset \(D=\left\{{x}_{i}, {y}_{i}\right), where i=\left(1, 2 ,3\dots n\right) and {x}_{i}\in {R}^{m}\text{ is the input vector having m number of input variables}\), and the output vector is denoted as \({y}_{i}\in R\). XGBoost uses the following objective function and regularization term presented in Eqs. (20) and (21):

where \(\Omega \left(.\right)\) and \(L(.)\) denote the regularization term and loss function, respectively. The loss function \(L(.)\) predicts the liquefiable and non-liquefiable conditions for a given training sample. In this context, "T" denotes the number of leaves in a decision tree, whereas \({\omega }_{j}\) represents the weight assigned to each leaf. By applying a second-order Taylor series expansion, Chen and Guestrin81 derived an approach to optimize this loss function, as illustrated in Eq. (22).

In this context, \(g_{i}\) and \(h_{i}\) represent the first and second derivatives of the loss function, respectively. The final predictive model is trained by incorporating y as the estimation for the \({i}^{th}\) instance at the \({t}^{th}\) iteration.

This equation assesses the suitability of a tree for the current step, but optimal values can be determined only after the tree structure is established. Owing to the impracticality of evaluating all possible structures, XGBoost constructs trees iteratively. XGBoost incorporates a regularization term \(\Omega\) and allows users to adjust two parameters: the maximum depth and the learning rate \(\eta\). The maximum depth, ranging from 0 to ∞ with a default of 8, limits tree depth, whereas (0< \(\eta\) < 1) scales the prediction of each tree, reducing overfitting and enhancing model performance.

Random forest (RF)

The RF model is a popular machine learning algorithm utilized to solve several complex and nonlinear problems at various scales. In this study, the RF model was utilized to assess the liquefaction success of soil by analyzing various input features related to soil and seismic conditions. The RF is constructed with the help of several ensembles of decision trees (DTs), where each DT is trained via a random data sample and input features. The diversity in the training subsets helps capture complex, nonlinear relationships between input variables and the likelihood of liquefaction. In the context of soil liquefaction prediction, the random forest model can handle a variety of input parameters, such as soil and seismic parameters (e.g., variables D, FC, \({a}_{max}\), \({q}_{c}\), \({\sigma }_{v}\), \({\sigma {\prime}}_{v}\), \({M}_{w}\), and \({R}_{f}\)). By voting on the predictions from multiple decision trees, the random forest model provides a robust estimate of the liquefaction potential of the soil.

One of the key advantages of using the random forest model in this context is its ability to handle large datasets and manage missing data without significant performance loss. It also offers insights into the importance of different features in predicting liquefaction, which can be valuable for understanding the key factors influencing soil behavior during seismic events. A total of 336 data cases were used for training the RF model, and 143 cases were used for testing. Using the training dataset, the link between the input factors and liquefaction was modeled, and the accuracy of the predictions was then determined via the testing dataset. The RF model can handle large databases and runs efficiently on thousands of input variables82. Overall, the random forest model is a powerful tool for assessing liquefaction risk, assisting in the development of effective mitigation strategies.

Long short-term memory

The long short-term memory (LSTM) model is a specialized type of recurrent neural network (RNN) that excels in learning and predicting sequences of data LSTM networks and was introduced by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber83. Since their introduction, LSTMs have been widely applied across diverse domains, including language modeling, speech recognition, and time series prediction. It is particularly useful in scenarios where temporal dependencies and sequential patterns are crucial, making it a promising approach for predicting the liquefaction potential of soil. In the context of soil liquefaction, the LSTM model can be used to analyze several soil and earthquake parameters that influence the liquefaction potential of soil during seismic events. Unlike traditional models, LSTMs can capture long-range dependencies and patterns in the data owing to their unique architecture, which includes memory cells and gating mechanisms. These components enable the model to retain relevant information from previous time steps and selectively forget irrelevant details, which is critical in understanding the cumulative effects of seismic events on soil stability. By leveraging historical data, such as past earthquake records and associated soil responses, the LSTM model can predict the likelihood of liquefaction under future seismic conditions. This predictive capability is particularly valuable for early warning systems and the planning of mitigation strategies. Moreover, LSTMs can incorporate various features, including soil properties, seismic characteristics, and environmental factors, providing a comprehensive assessment of liquefaction potential.

The memory cell, which is essential to long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, is engineered to maintain its state for extended periods of time. The network can then learn the dependencies that persist over time. Long short-term memory (LSTM) circuits regulate data entry and exit via three distinct types of gates: forget, input, and output. After deciding which input values to update the cell state with, it controls the output depending on the cell state and decides what information to discard. As relative information travels down the sequence chain, the cell state serves as a transport highway. It follows the entire chain in a straight line, with only a few small linear exchanges, enabling data to be transferred across numerous time steps.

The forget gate in an LSTM network is responsible for determining which information should be retained and which should be discarded. It processes the previous hidden state, \({h}_{t-1}\), and the current input, \({x}_{t}\), through a sigmoid activation function, as described in Eq. (23). The resulting output is a vector of values between 0 and 1, corresponding to each element in the cell state \({c}_{t-1}\). A value closer to 1 indicates that the information should be retained, whereas a value closer to 0 suggests that the information can be forgotten, thus enabling the network to manage long-term dependencies effectively.

where \(f\left(t\right)\) represents the output of the forget gate and where \({P}_{f}\) and \({b}_{f}\) represent the weight matrix and bias vector of the forget gates from the input layer, respectively.

The input gate decides which values will be updated. It has two parts: a sigmoid layer (deciding which values to update) and a \(tanh\) layer (creating a vector of new candidate values) via Eqs. (24) and (25).

The old cell state \({C}_{t-1}\) is updated into the new cell state \({C}_{t}\). This involves forgetting some parts of the old cell state and adding new candidate values via Eq. (26).

The output gate determines what the next hidden state \({h}_{t}\) should be. This is based on the cell state and involves passing it through a tanh function and then multiplying it by the output gate.

LSTM networks are powerful tools for handling sequences of data and have proven effective in a wide range of applications because of their ability to maintain long-term dependencies and manage the vanishing gradient problem typical of standard RNNs.

Bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM)

Bidirectional long short-term memory (BI-LSTM) networks represent advanced iterations of traditional LSTM networks engineered to enhance the comprehension of input sequences. Unlike standard LSTM networks, which process data in a unidirectional manner, BI-LSTM networks analyze sequences in both forward and backward directions. This bidirectional processing enables the model to access contextual information from both past and future inputs simultaneously. This architecture is especially advantageous in tasks that necessitate a comprehensive understanding of the full context, as it allows the network to capture dependencies and nuances that may otherwise be overlooked83.

In a Bi-LSTM network, each input sequence undergoes dual processing through two distinct LSTM networks. The first, known as the forward LSTM, processes the sequence from the initial element to the final element (from left to right). Conversely, the second network, the backward LSTM, processes the sequence in the reverse order, from the final element to the initial one (right to left). At each time step, the outputs generated by the forward and backward LSTM networks are concatenated. This concatenation allows the BI-LSTM to leverage information from both preceding and succeeding elements, thereby enhancing the model’s contextual understanding. This concatenation provides a comprehensive representation of the input at each time step, combining information from both directions. The input sequence is provided by \(X=[{x}_{1},{x}_{2},...,{x}_{T}]\), and the forward LSTM processes it in the original order to produce the forward hidden states \({\overrightarrow{h}}_{t}\) presented in Eq. (29).

After the forward LSTM process is forwarded, the reverse sequence is reserved, and the backward LSTM process produces the backward hidden states \({\overleftarrow{h}}_{t}\) via Eq. (30).

At each time step \(t\), the forward and backward hidden states are concatenated to form the final hidden state \({h}_{t}\), as presented in Eq. (31).

The concatenated hidden states \({h}_{t}\) are then used for subsequent layers or the final output layer, depending on the specific task. In this work, \({h}_{t}\) are used for the liquefaction classification system.

By processing the sequence in both directions, BI-LSTM can capture information from the entire sequence, leading to a better understanding of the context to overcome the limitations of the LSTM model. BI-LSTMs often achieve better performance on tasks that require context from both past and future inputs. BI-LSTM networks improve upon traditional LSTMs by integrating information from both preceding and succeeding contexts. This dual-directional approach makes them exceptionally effective for tasks requiring comprehensive sequence understanding, such as language processing and time series analysis. Consequently, BI-LSTMs provide richer, more accurate representations of input data, enhancing overall performance and contextual accuracy.

Performance assessment

The performance assessment of classification machine learning models is a critical aspect of the model development process. It involves evaluating how well a model predicts the class labels for new, unseen data. This assessment helps in understanding the model’s accuracy, robustness, and generalizability. A confusion matrix is a table that helps visualize the performance of a classification algorithm. It compares the actual target values with those predicted by the model. The calculation of several performance metrics is performed via the two-class confusion matrix shown in Fig. 4. True positives (TPs) are examples of the number of correctly predicted liquefiable cases that the algorithm properly recognizes as positive, whereas the negative components that are accurately classified as negative are known as true negatives (TNs). On the other hand, false negatives (FNs) are cases of positive data for which the ML models incorrectly classify the data as negative. The positive components that are incorrectly forecasted as negatives are known as false positives (FPs).

Various performance fitness error matrices (PFEMs) were calculated to assess the accuracy and reliability of the proposed models. The PFEMs included in this study are accuracy, recall, specificity, precision, F1 score, MCC, and balance accuracy (BA). The expressions for these PFEMs are presented in Eqs. (32) to (38).

ML model hyperparameter configuration

GridSearchCV is a powerful tool in the sci-kit-learn library that is used for hyperparameter tuning. This allows us to exhaustively search through a specified parameter grid and determine the optimal parameters for the XGBoost and RF algorithms. When the XGBoost and RF algorithms are used, GridSearchCV helps in finding the best combination of hyperparameters that leads to the highest performance of the model. Using GridSearchCV effectively requires a good understanding of the model and the problem at hand, allowing us to select an appropriate range of hyperparameters to explore. By systematically testing combinations of parameters such as the number of estimators, maximum tree depth, and learning rate, GridSearchCV identifies the configuration that yields the best model performance on the validation data. This approach ensures a more objective and data-driven selection of hyperparameters, reducing the reliance on manual trial-and-error. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the optimal values were determined based on defined search ranges for each algorithm. For example, the XGBoost model achieved optimal performance with 150 trees, a maximum depth of 6, and a learning rate of 0.1, whereas the RF model performed best with 200 trees and a maximum depth of 6. Although GridSearchCV is primarily applicable to traditional ML models, the hyperparameters for deep learning models such as LSTM and BI-LSTM were selected through empirical experimentation, as detailed in Table 4. These included settings such as the number of LSTM units, dropout rate, batch size, and training epochs. Together, these tuning strategies significantly contribute to enhancing model accuracy and robustness in the assessment of liquefaction potential.

Results and discussion

In this section, the classification of liquefaction and non-liquefaction prediction and performance evaluations of the proposed XGBoost, RF, LSTM, and BI-LSTM models are presented. A comparative analysis of the obtained classification results is performed on the basis of several PFEMs, confusion matrices, and classification results. The figures provided serve to illustrate the confusion matrix used for assessing liquefaction classification results. In these figures, an output class value of "1" is designated the positive class, which indicates the liquefaction case, whereas an output class value of "0" is labeled the negative class, which indicates the non-liquefaction case. Each figure is accompanied by a confusion matrix structure, placed under the respective headings, to visually represent the classification performance. Detailed analyses of the relevant data are conducted both before and after each figure is presented, ensuring a thorough interpretation of the results. This comprehensive approach allows for a deeper understanding of the classification process and its effectiveness. The dataset used in this study for liquefaction classification was divided into two parts: training and testing sets with a 70–30 split ratio. The training set was used to train the proposed ML models, and the testing set was used to validate their performance. The features in the dataset were standardized via Standard Scaler to ensure that each feature had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This step is particularly beneficial for models sensitive to feature scaling.

Classification results for the XGBoost model

The confusion matrices for the training and testing phases of the XGBoost model are shown in Fig. 5. During training, the model achieved 96 true positives and 212 true negatives, with 19 false positives and 8 false negatives, indicating a low misclassification rate. In the testing phase, the model correctly predicted 40 liquefaction cases and 86 non-liquefaction cases while misclassifying 8 and 10 instances, respectively. Overall, the results reflect strong classification performance. The few misclassifications may be attributed to the number of input features and data similarities between classes.

Classification results for the RF model

The confusion matrices for the training and testing phases are presented separately in Fig. 6. Upon examining Fig. 6 for the training phase, it is evident that the RF model correctly classified 99 true positive instances for the liquefaction cases and 215 true negative instances for the non-liquefaction cases in the training phase and 39 true positive instances for the liquefaction cases and 86 true negative instances for the non-liquefaction cases in the testing phase. As shown in Fig. 6, the RF model exhibited 16 false positives and 5 false negatives in the training phase and 9 false positives and 10 false negatives in the testing phase, indicating a relatively low misclassification rate.

Classification results for the LSTM model

The performance of the LSTM model is illustrated in Fig. 7. During the training phase, the model accurately classified 101 liquefaction (true positives) and 215 non-liquefaction cases (true negatives), with 14 and 5 misclassifications, respectively. In the testing phase, the model achieved 42 true positives and 84 true negatives, misclassifying 6 liquefaction cases and 12 non-liquefaction cases.

Classification results for the Bi-LSTM model

Figure 8 presents the BI-LSTM model results. During training, the model accurately classified 101 liquefaction (true positives) and 215 non-liquefaction cases (true negatives), with only 6 and 1 misclassifications, respectively. In the testing phase, the model correctly identified 42 liquefaction cases and 86 non-liquefaction cases, with 6 and 10 misclassifications, respectively.

Classification results and evaluation graphs of the models

The accuracy, specificity, precision, recall, F1 score, MCC, and BA values for each model were derived via confusion matrix data for the proposed ML models. The classification results for all the proposed ML models for liquefaction susceptibility prediction in both the training and testing phases are presented in Table 5, and the data corresponding to the models are depicted in Fig. 9 via a radar plot.

From the presented results analysis, it is evident that the proposed Bi-LSTM model has the highest classification prediction rate in both the training and testing phases. The proposed results of the PFEMs in Table 5 indicate that the developed BI-LSTM model achieves the highest accuracy rate of 97.91% in the training phase and 88.89% in the testing phase, followed by the LSTM (accuracy = 94.33% in training and 87.50% in testing), RF (accuracy = 93.73% in training and 86.81% in testing) and XGBoost (accuracy = 91.94% in training and 87.50% in testing) models. According to the results displayed in Table 5, the BI-LSTM model demonstrated superior performance across several key metrics. In addition to achieving the highest classification success rates, it performs excellently in terms of specificity, precision, recall, F1 score, MCC, and balanced accuracy (BA). This suggests that the proposed BI-LSTM model is highly effective for the liquefaction classification task. From the presented results, it can be concluded that advanced complex models such as LSTM and BI-LSTM offer significant performance improvements over ensemble ML models such as the XGBoost and RF models. However, the proposed XGBoost and RF models also performed well in assessing liquefaction classification.

In machine learning, accuracy and epoch loss curves are critical tools for understanding the performance of proposed models during the training and validation (val) phases. Accuracy measures the proportion of correct predictions made by the model out of all predictions. Accuracy is a simple yet informative metric, particularly in balanced datasets where the classes are roughly equal in number. Loss is a measure of how well the model’s predictions match the actual target values. It is a critical component in training the ML model algorithms. The epoch loss curves for all the proposed models are presented in Fig. 10. The presented curve is a plot that shows how the loss changes over the epochs during the training of the models. This curve also helps in understanding how well the model is learning for a given classification task. The presented results indicate that the proposed BI-LSTM model results in a consistently decreasing loss curve and increasing accuracy with increasing number of epochs, indicating that BI-LSTM is a highly effective model for liquefaction classification tasks on the basis of these training data. This trend suggests that the model’s performance improves with training, as it becomes better at minimizing prediction errors over time. The decreasing loss curve reflects the model’s increasing accuracy and effectiveness in learning from the data.

In this study, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for all the proposed models via both the training and test datasets, as shown in Figs. 11 and 12. The ROC curve provides a detailed assessment of the trade-off between the true positive rate (TPR) and the false positive rate (FPR) across different classification thresholds. The area under the curve (AUC) quantifies the model’s overall ability to distinguish between classes at all thresholds. The AUC was computed to evaluate the performance of each classifier. A higher AUC value signifies superior performance, with a value of 1 denoting a perfect classifier. The ROC curves for the BI-LSTM and LSTM models demonstrated excellent performance on both the training and test datasets. The BI-LSTM and LSTM models achieved AUCs of 0.96 and 0.97 on the training dataset and 0.89 and 0.88 on the test dataset, respectively, indicating a high true positive rate and a low false positive rate across various threshold values. The presented figures also show that the AUC values for the XGBoost and RF models are 0.86 and 0.91, respectively, in the training phase and 0.82 and 0.85, respectively, in the testing phase. The AUC value for all the proposed models is closer to 1, which means that the constructed model is suitable for liquefaction classification. These results suggest that the BI-LSTM and LSTM models effectively distinguish between the two classes in the dataset, outperforming the ensemble models. Although the XGBoost and random forest (RF) models also performed well, they did not attain AUCs as high as those of the BI-LSTM and LSTM models. The ROC curves for the ensemble models indicate good performance but are not as consistently high as those of the BI-LSTM and LSTM models.

SHapley additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis

Machine learning models used to assess liquefaction potential are often considered "black-box" models because of their lack of interpretability. These models produce predictions without offering insights into the factors driving those predictions, making it difficult to understand the underlying causes. To address this, the study employs SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAPs) to interpret the predictions of an XGBoost model. Developed by Lundberg et al.84. SHAP is a method that explains individual predictions by quantifying the contribution of each input feature to the model’s output. It is increasingly used in engineering and medical fields for building interpretable ML models, where SHAP has consistently shown promising results.

The SHAP method is grounded in game theory, particularly the concept of Shapley values, which were introduced by Shapley to fairly distribute payouts among players in a cooperative game on the basis of their contributions. In the context of machine learning, the “game” refers to the prediction task for each data instance, and the “players” are the input features that contribute to the predicted outcome. SHAP works as an additive feature attribution method, providing model-agnostic explanations that clarify how individual features influence predictions. This connection to local interpretable models helps bridge the gap between black-box machine learning models and human-understandable explanations.

The Shapley value for a feature i is computed by considering all possible coalitions (subsets of features) that include or exclude i and determining how much the prediction changes when feature i is added to those coalitions. The mathematical equation used for the Shapley value \({\phi }_{i}\) for a feature i is given by Eq. (39):

where \(N\) represents the number of input features, \(S\) is the subset of \(N\), which represents the nonzero entries, \(\left|S\right|\) is the number of features in the set \(S\), \({f}_{x}(S)\) represents the prediction of the model on the basis of the features in set \(S\), \({f}_{x}(S\backslash i)\) is the prediction of the model when feature i is added to the set \(S\), and \(\left|N\right|\) is the total number of features. The \({\phi }_{i}\) in Eq. (39) represents the SHAP value corresponding to any particular feature. Equation (39) essentially averages the contribution of feature i over all possible coalitions, ensuring that the contribution is fairly distributed on the basis of how much each feature impacts the model’s prediction when considered in various combinations.

SHAP plots

The SHAP technique calculates global feature importance by pooling local explanations. This method outperforms previous methods for determining feature importance and serves as a viable alternative to permutation feature importance. Unlike other approaches, the SHAP feature importance plot is based on the relevance of input variables in predictions, specifically their average impact on model output. As a result, differences in the order of the input variables may arise. The SHAP feature importance plot is shown as a horizontal bar chart, with each bar representing the mean absolute SHAP value of an input variable. These bars are sorted in descending order along the vertical axis according to their mean absolute SHAP values. The mean absolute SHAP value is computed by averaging the absolute SHAP values for a specific input variable throughout the whole dataset. Figure 13a shows the global feature importance plot. For this figure, the order of importance for the input variables in descending order is as follows:\({q}_{c}\), \({a}_{max}\), \({r}_{f}\), D, \({\sigma }_{v}\), \({M}_{w}\), FC and \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\). Notably, the most important input variable in the liquefaction potential assessment model is \({q}_{c}\), and \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\) is the least significant input variable among them.

The feature importance plot only shows the significance of the input parameters utilized in the liquefaction assessment. To provide more insight, a summary plot is presented in Fig. 13b, which combines feature importance with feature effects. The features are ordered by importance, and each case history is represented by a dot, with SHAP values shown on the horizontal axis. The dots on the right indicate a positive impact (increased liquefaction probability), whereas the dots on the left indicate a negative impact (i.e., decreased probability of liquefaction). The dots are colored from low (blue) to high (red) based on feature values, and the overlapping dots represent the SHAP value density. The figure shows that the parameter \({q}_{c}\) is the most significant parameter, followed by \({a}_{max}\), \({R}_{f}\), \(D\), \({\sigma }_{v}\), \({M}_{w}\), FC, and \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\). The parameter \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\) is the least significant parameter in assessing liquefaction classification.

The summary plot captures both positive and negative impacts of the input feature on the basis of the input parameter significance but cannot fully represent nonlinear patterns in SHAP values, as they vary with the input features. To address this limitation, SHAP dependence plots are more effective than partial dependence plots are. These scatter plots depict the input variable values on the horizontal axis and their corresponding SHAP values on the vertical axis. These plots reveal the impact of the input variables on the predictions, where positive SHAP values indicate increasing liquefaction potential, and negative values indicate decreasing potential, with higher absolute SHAP values representing stronger impacts in both directions. The Shap dependence plots for all the input variables, namely, \({q}_{c}\), \({a}_{max}\), \({r}_{f}\), D, \({\sigma }_{v}\), \({M}_{w}\), FC, and \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\), are presented in Fig. 14a–d, where the dots represent liquefied and non-liquefied cases.

The SHAP method effectively captures nonlinear relationships for the input parameters \({q}_{c}\), \({a}_{max}\), \({r}_{f}\), D, \({\sigma }_{v}\), FC and \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\), whereas such patterns are less clear for \({M}_{w}\). However, valuable insights can still be gained and validated via domain knowledge in liquefaction. Figure 14a shows a decreasing SHAP value for \({q}_{c}\), indicating a reduced probability of liquefaction, whereas Fig. 14b highlights significant changes in SHAP values for \({a}_{max}\), particularly between 0.2 and 0.3 \({a}_{max}\), after which the SHAP value stabilizes. Figure 14c indicates that as the value of \({r}_{f}\) increases beyond 2, the SHAP value drastically shifts to the negative side. Figure 14d shows an increasing trend in the SHAP values for depths between 2 and 6 m, whereas after 8 m, the SHAP values begin to decrease. Figure 14e shows a similar trend, where after a \({\sigma }_{v}\) value of 150, the SHAP value shows a decreasing trend. The SHAP values for \({M}_{w}\) change from negative to positive at approximately \({M}_{w}\) = 7, as shown in Fig. 14f, with minimal variation thereafter. For FC, a few higher values (approximately 80% or more) exhibit a negative SHAP trend, as shown in Fig. 14g. For \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\), the SHAP values shift from positive to negative at approximately 100, as shown in Fig. 14h, with discrepancies attributed to local conditions and limited case histories for higher values of \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\).

The SHAP dependence plot, by itself, is insufficient for fully capturing vertical variation arising from interactions between input parameters, as it does not account for complex interdependencies among variables. To study these interactions, each dot in the dependence plot is colored on the basis of the value of the interacting input features, as presented in Fig. 15. The color bars presented on the right side use blue and red to represent lower and higher interacting input feature values, respectively. For example, Fig. 15a shows that a higher \({a}_{max}\) value increases the liquefaction probability when \({q}_{c}\) is less than 8000. In Fig. 15b, a higher \({q}_{c}\) value decreases the liquefaction probability when \({q}_{c}\) exceeds 10,000. Similarly, Fig. 15c shows that a lower \({r}_{f}\) value and higher FC value increase liquefaction success. Figure 15d shows that a depth of approximately 4–10 m results in greater vertical stress, and above a depth of 10 m, the vertical stress tends to decrease. Figure 15e shows that a higher \({a}_{max}\) value increases liquefaction success at depths of approximately 5 m to 10 m. Figure 15f shows that a higher \({M}_{w}\) value increases liquefaction success at a higher value of \({q}_{c}\).

Conclusion

In contemporary geotechnical engineering, soil liquefaction has become a critical issue, particularly in seismic regions. This phenomenon poses significant risks to surface structures, transportation infrastructure, and even underground installations. As a result, it is essential to assess the liquefaction potential of a site, taking into account the specific ground conditions and seismic history of the region before any construction activities commence. Traditional methods for evaluating liquefaction risk are often subject to uncertainties due to the inherent variability in seismic and soil parameters. To address these challenges, various artificial intelligence (AI) approaches have been investigated as promising alternatives for estimating the liquefaction potential of soil deposits. Although numerous studies have explored the use of several machine learning (ML) techniques for predicting liquefaction, the application of deep learning (DL) methods remains relatively underexplored. However, our rigorous experiments indicate that DL models, particularly the LSTM and Bi-LSTM networks, offer superior predictive accuracy and robustness over ensemble ML techniques in predicting liquefaction susceptibility. Specifically, the BI-LSTM model obtained the highest accuracy of 97.91% in the training phase and 88.89% in the testing phase, followed by the LSTM, RF, and XGBoost models. The MCC and BA for the Bi-LSTM model are also greater than those of the other models. This advantage is largely due to their capacity to discern complex patterns and interactions within the data that traditional methods often overlook. The ROC curves for the BI-LSTM and LSTM models indicate the highest performance compared with the ensemble models XGBoost and RF. Additionally, the DL models BI-LSTM and LSTM demonstrate enhanced generalization capabilities, rendering them more reliable for practical applications. Furthermore, SHAP analysis is proposed for evaluating the liquefaction potential of soil deposits via the CPT database. According to the results of the SHAP analysis, the importance of the input features in descending order are \({q}_{c}\), \({a}_{max}\), \({r}_{f}\), D, \({\sigma }_{v}\), \({M}_{w}\), FC and \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\). The summary plot and feature importance plot provide further enhancement by combining feature importance with feature effects, revealing that \({q}_{c}\) is the most significant parameter for liquefaction assessment, whereas \({\sigma }_{v}{\prime}\) is the least significant. Future research directions include (i) integrating additional data sources, such as geospatial information and in situ sensor measurements, to enhance the model’s comprehension of soil conditions and real-time in situ sensor readings to provide a more comprehensive representation of subsurface conditions. (ii) Investigating advanced deep learning architectures, such as transformers, to capture more complex, nuanced relationships and capture high-dimensional patterns within geotechnical data, and (iii) developing explainable AI techniques to improve the interpretability and transparency of DL models, thereby fostering greater trust and facilitating wider adoption in practical geotechnical applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Finn, W. D., Bransby, P. L. & Pickering, D. J. Closure to “effect of strain history on liquefaction of sand”. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 98, 221–222 (1970).

Seed, H. B. & Peacock, W. H. Test procedures for soil liquefaction characteristics. ASCE J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 97, 1099–1119 (1971).

Seed, H. B. & Lee, K. L. Liquefaction of saturated sands during cyclic loading. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 92, 105–134 (1966).

Ishibashi, I. & Sherif, M. A. Soil liquefaction by torsional simple shear device. ASCE J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 100, 871–888 (1974).

Yoshimi, Y. & Oh-Oka, H. A ring torsion apparatus for simple shear tests. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 12, 89 (1975).

Seed, H. & Idriss, I. M. Simplified procedure for evaluating soil liquefaction potential. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 97, 1249–1273 (1971).

Boulanger, R. W. & Idriss, I. M. Liquefaction susceptibility criteria for silts and clays. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 132, 1413–1426 (2006).

Boulanger, R. W. & Idriss, I. M. CPT and SPT based liquefaction triggering procedures, Report UCD/CGM-10/2. Center for Geotechnical Modeling 1–138 (2014).

Robertson, P. K. & Campanella, R. G. Liquefaction potential of sands using the CPT. J. Geotech. Eng. 111, 384–403 (1985).

Olson, S. M. Liquefaction Analysis of Level and Sloping Ground Using Field Case Histories and Penetration Resistance. (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001).

Juang, C. H., Yuan, H., Lee, D.-H. & Lin, P.-S. Simplified cone penetration test-based method for evaluating liquefaction resistance of soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 129, 66–80 (2003).

Idriss, B. CPT and SPT based liquefaction triggering procedures. Center Geotech. Model. 1, 134 (2014).

Sahebzadeh, S., Heidari, A., Kamelnia, H. & Baghbani, A. Sustainability features of Iran’s vernacular architecture: A comparative study between the architecture of hot–arid and hot–arid–windy regions. Sustainability 9, 749 (2017).

Baghbani, A., Daghistani, F., Naga, H. A. & Costa, S. Development of a support vector machine (SVM) and a classification and regression tree (CART) to predict the shear strength of sand rubber mixtures. in Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Geotechnical Safety and Risk (ISGSR), Newcastle, Australia (2022).

Khajehzadeh, M., Taha, M. R., Keawsawasvong, S., Mirzaei, H. & Jebeli, M. An effective artificial intelligence approach for slope stability evaluation. IEEE Access 10, 5660–5671 (2022).

Lawal, A. I. & Kwon, S. Application of artificial intelligence to rock mechanics: An overview. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 13, 248–266 (2021).

Baghbani, A., Baghbani, H., Shalchiyan, M. M. & Kiany, K. Utilizing artificial intelligence and finite element method to simulate the effects of new tunnels on existing tunnel deformation. J. Comput. Cogn. Eng. 3, 166 (2022).

Dershowitz, W. S. & Einstein, H. H. Application of artificial intelligence to problems of rock mechanics. in The 25th US Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS) (OnePetro, 1984).

Baghbani, A., Costa, S., Faradonbeh, R. S., Soltani, A. & Baghbani, H. Experimental-AI investigation of the effect of particle shape on the damping ratio of dry sand under simple shear test loading (2023).

Baghbani, A. et al. Improving soil stability with alum sludge: An AI-enabled approach for accurate prediction of California bearing ratio (2023).

Nguyen, M. D. et al. Development of an artificial intelligence approach for prediction of consolidation coefficient of soft soil: a sensitivity analysis. Open Constr. Build. Technol. J. 13 (2019).

Baghbani, A., Choudhury, T., Samui, P. & Costa, S. Prediction of secant shear modulus and damping ratio for an extremely dilative silica sand based on machine learning techniques. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 165, 107708 (2023).

Baghbani, A., Costa, S., O’Kelly, B. C., Soltani, A. & Barzegar, M. Experimental study on cyclic simple shear behaviour of predominantly dilative silica sand. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 17, 91–105 (2023).

Nguyen, M. D. et al. Investigation on the suitability of aluminium-based water treatment sludge as a sustainable soil replacement for road construction. Transp. Eng. 12 (2023).

Baghbani, A., Daghistani, F., Baghbani, H. & Kiany, K. Predicting the strength of recycled glass powder-based geopolymers for improving mechanical behavior of clay soils using artificial intelligence. (2023).

Sihag, P., Suthar, M. & Mohanty, S. Estimation of UCS-FT of dispersive soil stabilized with fly ash, cement clinker and GGBS by artificial intelligence. Iranian J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 45, 901–912 (2021).

Baghbani, A., Daghistani, F., Kiany, K. & Shalchiyan, M. M. AI-based prediction of strength and tensile properties of expansive soil stabilized with recycled ash and natural fibers. (2023).

Gullu, H. On the prediction of unconfined compressive strength of silty soil stabilized with bottom ash, jute and steel fibers via artificial intelligence. Geomech. Eng. 12, 441–464 (2017).

Baghbani, A., Daghistani, F., Baghbani, H., Kiany, K. & Bazaz, J. B. Artificial intelligence-based prediction of geotechnical impacts of polyethylene bottles and polypropylene on clayey soil. (2023).

Bhasin, R., Kaynia, A. M., Paul, D. K., Singh, Y. & Pal, S. Seismic behaviour of rock support in tunnels. in Proceedings 13th Symposium on Earthquake Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee (2006).

Pal, M. Support vector machines-based modelling of seismic liquefaction potential. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 30, 983–996 (2006).

Samui, P. Seismic liquefaction potential assessment by using relevance vector machine. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 6, 331–336 (2007).

Hasanipanah, M., Monjezi, M., Shahnazar, A., Jahed Armaghani, D. & Farazmand, A. Feasibility of indirect determination of blast induced ground vibration based on support vector machine. Measurement (Lond) 75, 289–297 (2015).

Samui, P., Kumar, R., Yadav, U., Kumari, S. & Bui, D. T. Reliability analysis of slope safety factor by using GPR and GP. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37, 2245–2254 (2019).

Pradeep, T., Bardhan, A., Burman, A. & Samui, P. Rock strain prediction using deep neural network and hybrid models of anfis and meta-heuristic optimization algorithms. Infrastructures (Basel) 6 (2021).

Pradeep, T., Bardhan, A. & Samui, P. Prediction of rock strain using soft computing framework. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 7, 37 (2022).

Yegnanarayana, B. Artificial neural networks for pattern recognition. Sadhana 19, 189–238 (1994).

Hema, H., Chakravarthy, H. G. N. & Naganna, S. R. Prediction of ultimate load carrying capacity of short cold-formed steel built-up lipped channel columns using machine learning approach. Sadhana 47, 207 (2022).

More, S. B., Deka, P. C., Patil, A. P. & Naganna, S. R. Machine learning-based modeling of saturated hydraulic conductivity in soils of tropical semi-arid zone of India. Sadhana 47, 26 (2022).

Balachandar, C., Arunkumar, S. & Venkatesan, M. Computational heat transfer analysis and combined ANN—GA optimization of hollow cylindrical pin fin on a vertical base plate. Sadhana 40, 1845–1863 (2015).

Ghani, S., Kumari, S. & Bardhan, A. A novel liquefaction study for fine-grained soil using PCA-based hybrid soft computing models. Sadhana—Academy Proceedings in Engineering Sciences 46, 1–17 (2021).

Ghani, S. & Kumari, S. Probabilistic study of liquefaction response of fine-grained soil using multi-linear regression model. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series A 102, 783–803 (2021).

Kumar, D. R., Samui, P. & Burman, A. Prediction of probability of liquefaction using soft computing techniques. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A 103 (2022).

Kumar, D. R., Samui, P. & Burman, A. Determination of best criteria for evaluation of liquefaction potential of soil. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 1–20 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40515-022-00268-w.

Kumar, D. R., Samui, P. & Burman, A. Prediction of probability of liquefaction using hybrid ANN with optimization techniques. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1587 (2022).

Zhao, H. B., Ru, Z. L. & Yin, S. Updated support vector machine for seismic liquefaction evaluation based on the penetration tests. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 25, 209–220 (2007).

Hanna, A. M., Ural, D. & Saygili, G. Neural network model for liquefaction potential in soil deposits using Turkey and Taiwan earthquake data. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 27, 521–540 (2007).

Das, S. K. & Muduli, P. K. Evaluation of liquefaction potential of soil using extreme learning machine. Comput. Methods Geomech. Front. New Appl. 1, 548–552 (2011).

Muduli, P. K. & Das, S. K. First-order reliability method for probabilistic evaluation of liquefaction potential of soil using genetic programming. Int. J. Geomech. 15, 04014052 (2015).

Xue, X. & Liu, E. Seismic liquefaction potential assessed by neural networks. Environ. Earth Sci. 76, 1–15 (2017).

Zhang, W. & Goh, A. T. C. Evaluating seismic liquefaction potential using multivariate adaptive regression splines and logistic regression. Geomech. Eng. 10, 269–284 (2016).

Goh, A. T. C. & Zhang, W. G. An improvement to MLR model for predicting liquefaction-induced lateral spread using multivariate adaptive regression splines. Eng. Geol. 170, 1–10 (2014).

Rahman, M. S. & Wang, J. Fuzzy neural network models for liquefaction prediction. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 22, 685–694 (2002).

Liu, J. Influence of fines contents on soil liquefaction resistance in cyclic triaxial test. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 4735–4751 (2020).

Naik, S. P. & Patra, N. R. Generation of liquefaction potential map for Kanpur city and Allahabad city of northern India: An attempt for liquefaction hazard assessment. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 36, 293–305 (2018).

Acharya, P., Sharma, K., Acharya, I. P. & Adhikari, R. Seismic liquefaction potential of fluvio-lacustrine deposit in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Geotechn. Geol. Eng. 1–21 (2023).

Khan, S. & Kumar, A. Identification of possible liquefaction zones across Guwahati and targets for future ground improvement ascertaining no further liquefaction of such zones. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 1747–1772 (2020).

Pancholi, V., Dwivedi, V., Bhatt, N. Y., Choudhury, P. & Chopra, S. Geotechnical investigation for estimation of liquefaction hazard for the Capital City of Gujarat State, Western India. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 6551–6570 (2020).

Talebi Mamoudan, H. R., Kalantary, F., Derakhshandi, M. & Ganjian, N. Probabilistic and deterministic assessment of liquefaction potential using piezocone data. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39, 533–547 (2021).

Jha, S. K., Karki, B. & Bhattarai, A. Deterministic and probabilistic evaluation of liquefaction potential: A case study from 2015 Gorkha (Nepal) earthquake. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 4369–4384 (2020).

Jas, K. & Dodagoudar, G. R. Explainable machine learning model for liquefaction potential assessment of soils using XGBoost-SHAP. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 165, 107662 (2023).

Zhong, B., Xing, X., Love, P., Wang, X. & Luo, H. Convolutional neural network: Deep learning-based classification of building quality problems. Adv. Eng. Inform. 40, 46–57 (2019).

Fang, Z. et al. Deep learning-based axial capacity prediction for cold-formed steel channel sections using Deep Belief Network. in Structures vol. 33 2792–2802 (Elsevier, 2021).

Tiwari, S. K., Kumaraswamidhas, L. A., Prince, Kamal, M. & Rehman, M. ur. A hybrid deep leaning model for prediction and parametric sensitivity analysis of noise annoyance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25509-4.

Kumar, M., Ranjan, D. & Warit, K. Deep learning and genetic programming-based soft-computing prediction models for metakaolin mortar. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40515-025-00532-9 (2025).

Kumar, M., Kumar, D. R., Khatti, J., Samui, P. & Grover, K. S. Prediction of bearing capacity of pile foundation using deep learning approaches. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 1–17 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-024-1085-z.

Khatti, J. & Grover, K. S. Prediction of compaction parameters of compacted soil using LSSVM, LSTM, LSBoostRF, and ANN. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 8, 76 (2023).

Khatti, J. & Grover, K. S. CBR Prediction of pavement materials in unsoaked condition using LSSVM, LSTM-RNN, and ANN approaches. Int. J. Pav. Res. Technol. 17, 750–786 (2024).

Ghanizadeh, A. R., Aziminejad, A., Asteris, P. G. & Armaghani, D. J. Soft computing to predict earthquake-induced soil liquefaction via CPT results. Infrastructures (Basel) 8, 125 (2023).

Ghani, S. & Kumari, S. Probabilistic study of liquefaction response of fine-grained soil using multi-linear regression model. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A 102, 783–803 (2021).

Ghani, S. & Kumari, S. Liquefaction behavior of Indo-Gangetic region using novel metaheuristic optimization algorithms coupled with artificial neural network. Nat. Hazards 111, 2995–3029 (2022).

Kumar, D., Samui, P., Kim, D. & Singh, A. A novel methodology to classify soil liquefaction using deep learning. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39, 1049–1058 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Xie, Y., Zhang, Y., Qiu, J. & Wu, S. The adoption of deep neural network (DNN) to the prediction of soil liquefaction based on shear wave velocity. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 5053–5060 (2021).

Kumar, D. R., Samui, P., Burman, A., Wipulanusat, W. & Keawsawasvong, S. Liquefaction susceptibility using machine learning based on SPT data. Intell. Syst. Appl. 20, 200281 (2023).

Ghani, S., Thapa, I., Adhikari, D. K. & Waris, K. A. Soil categorization and liquefaction prediction using deep learning and ensemble learning algorithms. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 12, 22 (2025).

Idriss, I. M. & Boulanger, R. W. Soil Liquefaction during Earthquakes. Earthquake Engineering Research Institute vol. 136 (Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, 2008).

Boulanger, R. W. High overburden stress effects in liquefaction analyses. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 129, 1071–1082 (2003).

Robertson, P. K. & Wride, C. E. Evaluating cyclic liquefaction potential using the cone penetration test. Can. Geotech. J. 35, 442–459 (1998).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 1189–1232 (2001).

Kumar, D. R., Samui, P. & Burman, A. Prediction of probability of liquefaction using soft computing techniques. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A 103, 1195–1208 (2022).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining vols 13–17-Augu 785–794 (2016).