Abstract

In the time of advancing medical technology, there is a critical issue concerning the misdiagnosis of diseases. The aim of this research is to significantly reduce the occurrence of misdiagnoses in medical practice by leveraging hypergraphs and genomic data to improve diagnostic accuracy. We have designed and implemented a sophisticated computational framework for phenotype-driven disease prediction that leverages hypergraphs and genomic data to enhance the accuracy of disease identification, leading to more precise and timely treatments for patients. The study employed robust ranking algorithms, on a sample of 2130 diseases, 4655 genes and 9541 phenotypes collected from reliable sources of Orphanet and Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) database to achieve highly favorable outcomes. The proposed method outperforms existing state-of-the-art tools such as Phenomizer and GCN, in terms of both prediction accuracy and processing speed. Notably, it captures 50% of causal genes within the top 10 predictions and 85% within the top 100 predictions and the algorithm maintains a high accuracy rate of 98.09% for the top-ranked gene. In conclusion, our study demonstrated the effectiveness of robust ranking algorithms and hypergraph framework in achieving accurate and reliable results for disease diagnosis. While the study provides valuable insights, it is important to note its limitations, such as the sample size and scope of diseases considered. Future research could explore the integration of additional data sources and refinement of algorithms to further enhance diagnostic capabilities. Overall, this study underscores the potential of algorithmic hypergraph based approaches in advancing medical diagnostics and improving healthcare delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional disease prediction methodologies, although valuable, are not necessarily precise because of ignorance of factors other than the symptoms indicating the presence or absence of a disease. Genomics data, including a person’s entire genetic makeup, can act as the basic component for determining diseases’ genetic basis. With the introduction of new-age technologies, genomics data has become easily accessible. The rise of high-throughput genomics technologies has provided researchers with extensive datasets, enabling different algorithms and data structures to unravel the genetic factors of diseases efficiently.

Advances in genomic technologies have opened up new possibilities in rare disease diagnosis. Due to their rarity, such illnesses are difficult to diagnose and research. As a result, rare disease patients frequently have prolonged or incorrect diagnoses, which makes it difficult for them to get the right care and assistance. While each rare disease by itself impacts a limited number of people, collectively, it affects millions across the globe. As the unknowns behind these diseases are gradually resolved with genetic knowledge, cutting-edge methods like precision medicine and genome sequencing give affected people and their families hope for better diagnosis, care, and support.

Phenotype-driven prediction, focusing on observable traits due to the interaction of genes and the environment, provides a promising approach for successful diagnosis. Understanding the link between an individual’s observable traits and underlying genetic makeup is pivotal for early disease diagnosis, targeted therapy, and personalized healthcare. PhenIX1 primarily focuses on known Mendelian disease genes for variant prioritization. In contrast, Exomiser1 incorporates model organisms and gene discovery, which impacts its performance. The difference in approach is a crucial factor in the varying results produced by these approaches. Phenotype-driven analyses can be effective in diagnosing genetic diseases from clinical exomes. However, the performance of these analyses depends on the specific tool used and its alignment with the phenotype of the disease under investigation.

A hypergraph is a generalization of a graph in which an edge can join any number of vertices. In contrast, in an ordinary graph, an edge connects exactly two vertices. Hypergraphs are often represented using a loop around all the vertices connected by the edge. In a hypergraph, a set of elements is called nodes, vertices, points, or elements, and another set is a set of pairs of subsets, called an edge or hyperedge. The vertex subset is known as its tail or domain, and as its head or codomain. The order of a hypergraph is the number of vertices, and the size of the hypergraph is the number of edges. Hypergraphs are useful to model real-life problems, and can express associations among any number of data entities. By capturing higher-level correlations, hypergraph models represent data that may contain multi-way relationships2. Researchers have recently used hypergraph models for various tasks, such as prediction of protein-protein interaction3, drug-target interaction4, drug-drug interaction5, essential genes in multi-protein dataset6, and critical genes for pathogenic viral response7. This ability to capture higher-level relations between graph nodes makes hypergraphs ideal for representing the multifaceted relationships inherent in genetic data, where genes contribute simultaneously to multiple phenotypic traits and diseases. As this can lead to more precise disease prediction8, our study uses graph-based techniques to improve the predictive effectiveness of phenotype-driven disease models.

The previous works rely on generating inferred associations from the already present associations between biological entities, using semantic similarity. These transformations applied to graphs have limited capabilities for expressing complex relations of omics data. In addition to analyzing and predicting relations between different parts of the gene, phenotype, and disease, many other tools have their scope narrowed to individual components, such as processing and analyzing a patient’s genotype or phenotype data. These tools do not narrow down the diseases to a considerable extent, i.e., they have a low precision score. These approaches do not specifically demonstrate detail accuracy metrics, or integrate different rare genetic disease datasets with association weights. Regarding phenotype-driven disease prediction, while existing approaches like PDR, Phenomiser, and Phen2Gene have successfully set the stage for leveraging patient phenotypes to predict the disease as precisely as possible, these methods cannot learn inferred associations that are not present in the dataset. Many of these tools are also inefficient or simply are not built for identifying the influential gene for each disease.

Our study aims to address these gaps by systematically evaluating hypergraph methods for gene prioritization, as hypergraphs can capture such multipartite relationships compared to standard graphs. It also discusses different ranking algorithms that provide a data-driven approach to prioritize candidate disease genes.

This study presents a novel approach by designing and implementing a sophisticated computational framework for phenotype-driven disease prediction that leverages hypergraphs and genomic data to significantly reduce the occurrence of misdiagnoses in medical practice.

Our work makes the following contributions-

-

The development of a predictive model capable of precisely determining causal genes based on phenotypes.

-

The development of a predictive model capable of precisely determining diseases based on phenotypes.

We test our strategy using large datasets, evaluating its effectiveness compared to other approaches, such as the widely used HANRD9 and Phenomizer10 tools. We aim to demonstrate the potential of our approach in reconsidering disease diagnosis and treatment approaches.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Section “Existing work” reviews the relevant existing work. Section “Methodology” explains the methodology followed, the data set curated, and the application of hypergraphs in modeling genomics data. Section “Results” describes the results of our evaluations, followed by a discussion of the same in Section “Discussion”. Finally, Section “Conclusion”, summarizes the work done and concludes the article.

Existing work

Rare diseases

There have been multiple tools developed to help with rare disease diagnosis.

FindZebra11 is a type of search engine that is used to suggest a set of diseases based on the symptoms provided. However, this association is not taking into consideration gene-phenotype-disease interactions. This was addressed by making use of Graph convolution networks for inferring relationships.

Rao et al.9 talk about a method that is influenced mainly by phenotypes for gene prioritization by making use of a heterogeneous network that comprises of genes, phenotypes and pathways. Similarly,12 shows PRIORI-T which makes use of a correlation network taken from the abstracts of MEDLINE articles and refines them using GCNs.

Alves et al.13 developed a tool driven by symptoms that matches those present in Orphanet14. It makes use of a metric that readjusts based on symptom overlap.

Ullah et al.15 make use of bipartite graphs that links symptoms, genes and diseases which have been assigned weights by path frequency. When compared against Phenomizer, it is a better tool for ranking diseases.

The studies discussed above mainly learn new associations based on existing data primarily depending on semantic similarity. They do have limitations of not being able to analyze multiomics data. Moreover, some of these tools focus on just genotypes or phenotypes instead of a more broader viewing.

Causal genes

A thorough review of population genetics, GWAS, sequencing, and computational techniques for locating causative alleles in complex disorders is given by Raychaudhuri16, with a focus on statistical approaches for variant finding and interpretation.

Phenotypic Driven Ranking (PDR), a network-based method that ranks diseases and genes by phenotypic relevance, is introduced by A. Krämer et al.17. It outperforms Phenolyzer in discovering causal genes in uncommon conditions such as Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome.

In order to successfully identify known illness genes and forecast novel possibilities, Greene et al.18 construct a Bayesian regression method called ‘phenotype similarity regression’ that uses the Human Phenotype Ontology to correlate rare genotypes with phenotypes.

Buphamalai et al.19 investigate rare disease gene abnormalities using a 46-layer multiplex network, which allows information transfer between diseases and reliably ranks causal genes.

Phenotype Consensus Analysis (PCAN), a R package that measures phenotype similarity in gene networks, is presented by Godard et al.20. It helps identify genes that are linked to disorders and facilitates gene discovery.

WGS and WES are used in congenital heart disease (CHD) by Tan et al.21, who achieved a 34.7% diagnosis rate and shown the value of integrated sequencing in determining candidate genes and genetic causes.

In their comparison of trio-CES with proband-CES for the diagnosis of uncommon Mendelian disorders, H. Lee et al.22 demonstrate that trio-CES greatly enhances the detection of de novo and compound heterozygous variations, especially in developmental delay and retinal abnormalities.

Chong et al.23 show the value of patient-driven data sharing in rare Mendelian gene discovery by using social networking to find KDM1A mutations in a novel developmental disease.

Wang et al.24 confirm the function of TGM6 as a causative gene by identifying a new mutation associated to spinocerebellar ataxia by linkage analysis and exome sequencing.

In order to enhance gene discovery and illness comprehension, these research highlight the significance of combining various data kinds, utilizing statistical and computational techniques, and implementing network-based methodologies.

Phenotype-driven disease prediction

Phenotype-driven computational algorithms improve variant prioritization and unusual disease diagnosis by prioritizing genes in exome sequencing based on patient features compared to known disease gene phenotypes25,26.

Krämer et al.17 introduce Phenotype Driven Ranking (PDR), a component of Ingenuity Variant Analysis that employs phenotype-disease-gene correlations from the QIAGEN Knowledge Base to efficiently prioritize diseases and genes.

Phenomizer10 rates diseases according to the semantic similarity between patient symptoms and known disorders and assigns p-values for statistical validation.

Pengelly et al.1 developed PhenIX for clinical diagnostics in spite of their shortcomings in novel gene discovery. LIRICAL and AMELIE27 combine genotype and phenotype data to prioritize genes that cause Mendelian disorders.

Oligogenic diseases provide a database for ranking variant combinations according to gene interactions and gene-phenotype associations28. By using well-established information of gene interactions, this resource aids in prioritizing genetic variations.

This problem is approached differently by several tools. PhenoVar29 provides genetic diagnosis scores based on OMIM, whereas Phen2Gene30 assesses genes using a probabilistic model and the HPO2Gene Knowledgebase (H2GKB).

Both established and new gene-phenotype connections are successfully identified using Phenogenon31. By examining HPO keywords, variation frequencies, and pathogenicity scores, for instance, it has connected RRAGA to skin abnormalities, providing important information about rare disorders.

Researchers have looked into a hypergraph-based architecture that combines phenotypic and genomic data for improved variant prioritization in order to improve disease prediction and optimize datasets. Smith et al.32 show that addition of phenotype-driven features to machine learning models greatly increases predictive accuracy when compared to genomic data alone.

Hypergraphs in biological networks

A hypergraph G, as shown in Fig. 1, is a pair (V, E), where V is the vertex set and E is a family of non-empty subsets of V called hyperedges. Hypergraphs are graphical structures that do well at capturing group interactions rather than individual interactions, thus making them eligible to perform tasks that involve inferring or generating new associations. Mathematical and graphical methods have been used to analyze biology networks8. Protein-protein interaction networks have known to struggle to capture complex interactions33.

In these cases, hypergraphs prove to be useful in capturing these relationships which makes it efficient for cellular and brain network modeling2,8,34. Additionally, for visualization we have tools like Hyperscape35.

Hypergraphs find extensive use especially in the field of Cancer Systems Biology8, disease ranking36. They are also used in recognizing the key genes in host-virus interactions7. One of the studies have improved gene-disease prediction by making use of hypergraphs along with CNNs37. Some other studies have introduced HRPR, thus achieving an overall accuracy of 19.7% for rare diseases.

In our study, we focus on constructing phenotype-gene and disease-gene hypergraphs, transforming the concept of disease prediction as a ranking problem. We also aim to improve the accuracy by inferring relationships from complex interactions.

Other existing machine learning techniques

AI applications in Parkinson’s disease (PD) detection are examined by Mahmoud Ibrahim and Abed Mohammed38 using MRI, EEG, handwriting, and speech analysis. CNNs and hybrid models are examples of machine learning models that achieve high accuracy (up to 99.9% in EEG-based identification and 84.5%-99.2% in handwriting and speech). Issues include dataset imbalance, multimodal data integration, and interpretability of AI. The integration of clinical, genetic, and imaging data, the prediction of disease development, and federated/transfer learning for model robustness are the main areas of future research.

Another study39 focuses on reviewing ML applications with respect to research in multi-omics cancer. They analyze the performance of SVM, RF, KNN, DNN, CNN and autoencoders for classifying cancer, identification of subtypes and biomarker discovery. Some of their limitations include data dimensions and model interpretability.

These studies discussed above make use of ML for disease analytics. However, it has been knows that traditional ML models cannot perform will with complex multiomics data interactions. In such cases, the integration of such models with a hypergraph architecture offers a superior representation capturing the higher-order relationships. Our study makes use of a similar hypergraph architecture for phenotype-driven disease prediction thus improving the accuracy and helps focusing on more precise treatments.

The methodologies discussed are summarized in Table 1, highlighting their focus, key techniques and research gaps.

Methodology

Data integration

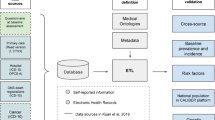

The dataset used in this study comprises disease, gene, and phenotype entities. The disease-phenotype associations were derived from Orphanet14 and the phenotype-gene associations were primarily derived from the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) database41. Along with these associations, the weights for the phenotype-gene associations were determined using the information content (IC) scores for the corresponding phenotype-gene pair from PyHPO which is a Python library for parsing and analyzing the HPO database. Information content is a measure that tells us how closely associated a phenotype and gene are, based on their co-occurrence in relevant disease-related studies. The integration process is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The weights were normalized using the standard normalization process and aggregated by adding the scores of the set of genes responsible for the expression of the particular phenotype. These weights are subsequently used to determine the gene rankings.

The original dataset compiled from the Orphanet and HPO database has 2130 diseases, 4655 genes and 9541 phenotypes, as shown in Table 2.

Weights for disease-gene associations were obtained from Disease Ontology and Phenolyzer42. Further results proved the validity of the Phenolyzer42 scores over the Disease Ontology scores. These weights were also normalized using standard normalization and added to our dataset for further steps. The entire dataset was stored as a parquet file for easy sharing and minimizing memory usage. These weights derived from Phenolyzer42 have the data for 3037 diseases and 56452 genes. The combined original datasets from Phenolyzer and Disease Ontology were able to map the associations for 1746 diseases, i.e., the overlap between the two datasets was 1746 diseases. Therefore, the final combined dataset43, has data for 1746 diseases, 1764 genes and 8507 phenotypes.

Hypergraph construction

Constructing the phenotype-gene and gene-disease hypergraphs required new approaches to handle the scale and connectivity of biomedical data. The phenotype-gene hypergraph was constructed with phenotypes as hyperedges and genes as nodes, whereas the gene-disease hypergraph was constructed with disease as nodes and genes as hyperedges, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This was done to aid with efficient traversal tailored to work with our ranking algorithms. We implemented a parallel construction algorithm using Python’s multiprocessing. The nodes and edges were distributed across processes with coordination via shared memory and semaphores. This allowed building hypergraphs with \(\tilde{4}\)K nodes and \(\tilde{2}0\)M hyperedges on a compute cluster. The hypergraphs were stored in a shareable format without duplication to minimize memory usage.

Ranking algorithms

We developed a modular framework to implement and evaluate different node ranking algorithms on the hypergraphs. Algorithms were optimized to leverage the hypergraph structure and edge weights. The methodology followed with ranking algorithms is outlined in Fig. 4. The ranking performance was evaluated on disease diagnosis test cases taken from HANRD (Rao et al.9 talk about a method that is influenced mainly by phenotypes for gene prioritization by making use of a heterogeneous network that comprises of genes, phenotypes and pathways. They have compiled this dataset from HANRD for the purpose of testing the algorithms).

By comparing the various approaches enlisted below, we found that integrating multiple data types (e.g. phenotypes, ontology, curated databases) improved ranking accuracy. This demonstrated the utility of heterogeneous hypergraphs for combining diverse biomedical evidence.

Phenotype-based gene ranking

This approach leveraged the phenotype-gene hypergraph to rank genes based on their associations with the input phenotype. In Algorithm 2 and Algorithm 3, HgraphTraversalDict is the phenotype-gene hypergraph and disease-gene hypergraphs and geneICweights refer to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations. For a given phenotype, we queried the hypergraph to retrieve all genes connected to that phenotype node. The term ‘item’ from the algorithm stands for the genes associated with the input phenotype. The information content scores for each phenotype-gene edge were summed per gene and used to generate a ranked list of genes, using our helper Algorithm 2, prioritizing those with stronger associations to the input phenotype. This allowed us to capture the relative importance of each gene based on the specificity of its phenotype associations. We then used these genes to traverse through the second hypergraph to obtain the disease ranking by adding the per-gene weight, using our helper Algorithm 3, for each disease-gene association. The term ‘key’ in this algorithm refers to the diseases that are associated with the ranked list of genes obtained through the previous helper Algorithm 2. The top 5, 10, 15, and 20 ranked diseases were evaluated as predictions.

Gene-based disease ranking

This approach-Algorithm 5, leveraged the phenotype-gene hypergraph to rank genes based on the number of occurrences with the input phenotype. In Algorithm 5, genePhenotypeGroups refers to the phenotype-gene associations, diseaseGeneGroups refers to the disease-gene associations, geneICweights refers to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations and testCases are the ground truth values of disease diagnosis from the HANRD paper. For a given phenotype, we queried the hypergraph to retrieve all genes connected to that phenotype node and only considered the genes with the maximum occurrence, using Algorithm 1, as our curated gene list. The top-ranking genes from this list were used to query the gene-disease hypergraph. For each of these genes, we looked at all connected disease nodes and tallied the number of occurrences per disease across the genes. By summing the disease occurrences, we obtained a ranking of diseases, using Algorithm 1, prioritizing those that were most frequently associated with the top phenotype-related genes. This helped uncover diseases that were strongly linked to the genotype patterns underlying the phenotype.

Weighted gene-based disease ranking

This approach-Algorithm 6, was similar to the gene-based ranking but additionally incorporated external gene-disease association scores from curated databases. In Algorithm 6, genePhenotypeGroups refers to the phenotype-gene associations, diseaseGeneGroups refers to the disease-gene associations, geneICweights refers to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations and testCases are the ground truth values of disease diagnosis from the HANRD paper. This approach was implemented twice wherein, the edge weights for each gene-disease association were defined as normalized scores from DISEASES for the first implementation and Phenolyzer42 for the second implementation. When ranking diseases connected to the top phenotype-related genes, the weights were summed instead of occurrences, using Algorithm 3 integrating evidence from both the hypergraph topology and external disease databases. The top 5, 10, 15, and 20 ranked diseases were evaluated as predictions.

Weighted gene-based weighted disease ranking

This approach-Algorithm 7, was a combination of the phenotype-based gene ranking, and weighted gene-based disease ranking where the genes were obtained using IC (Information Content) weights, and these genes were used to query diseases from disease-gene hypergraphs. In Algorithm 7, genePhenotypeGroups refers to the phenotype-gene associations, diseaseGeneGroups refers to the disease-gene associations, geneICweights refers to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations, testCases are the ground truth values of disease diagnosis from the HANRD paper and gdascores are the weights given to the disease-gene associations. These diseases were then ranked using their cumulative gene-disease association score from Phenolyzer42 and DISEASE database, using Algorithm 2. Once again, the top 5, 10, 15, and 20 ranked diseases were evaluated as predictions.

Hybrid ranking

This method-Algorithm 8, combined both phenotype-based gene prioritization and weighted disease ranking. In Algorithm 8, genePhenotypeGroups refers to the phenotype-gene associations, diseaseGeneGroups refers to the disease-gene associations, geneICweights refers to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations, testCases are the ground truth values of disease diagnosis from the HANRD paper and gdascores are the weights given to the disease-gene associations. First, the phenotype-gene hypergraph was used to rank genes by normalized information content like the first approach. Then the top-1,2,3,5,10 and 20 genes were retained in six different trials and used to rank diseases by maximum occurrences in the gene-disease hypergraph, using Algorithm 1. The goal was to account for phenotype specificity in gene ranking but still leverage external disease knowledge when linking to diseases.

Accumulated disease weight based ranking

This method-Algorithm 9 combined phenotype-based gene prioritization and accumulated weighted disease ranking. In Algorithm 9, genePhenotypeGroups refers to the phenotype-gene associations, diseaseGeneGroups refers to the disease-gene associations, geneICweights refers to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations, testCases are the ground truth values of disease diagnosis from the HANRD paper and gdascores are the weights given to the disease-gene associations. First, the phenotype-gene hypergraph was used to rank genes by normalized information content like the first approach. Then the top-1,2,3,5,10 and 20 genes were retained in six different trials and used to rank diseases by adding individual gene weights (from the first ranking) and gene-disease association score (taken from the Phenolyzer Database) in the gene-disease hypergraph, using our helper Algorithm 4.

Accumulated disease weight based hybrid ranking

This method-Algorithm 10, combined both phenotype-based gene prioritization, accumulated weighted disease ranking and gene-based disease ranking. In Algorithm 10, genePhenotypeGroups refers to the phenotype-gene associations, diseaseGeneGroups refers to the disease-gene associations, geneICweights refers to the weights for the phenotype-gene associations, testCases are the ground truth values of disease diagnosis from the HANRD paper and gdascores are the weights given to the disease-gene associations. First, the phenotype-gene hypergraph was used to rank genes by normalized information content like the first approach. Then the top-1,2,3,5,10 and 20 genes were retained in six trials and used to rank diseases by maximum occurrences, using Algorithm 1. This gives us the curated disease list. Then, subsequently add individual gene weights (from the first ranking) and gene-disease association score (taken from the Phenolyzer Database) in the gene-disease hypergraph for the diseases from our curated list.

The developed ranking algorithms, operate on a heterogeneous graph representation of disease and gene associations, leveraging a hypergraph-based modeling strategy to encode higher-order relationships. By utilizing association weights between diseases, genes, and phenotypes, the algorithms provide a generic computational framework applicable to diverse disease contexts, given comprehensive association data. The methods are not intrinsically restricted to rare diseases, rather, the use of a complex hypergraph structure allows capturing the multifaceted effects and relationships implicated across different diseases and genetic influences.

These ranking algorithms, are demonstrated on rare diseases but, provide a widely applicable algorithmic framework for integrated analysis of heterogeneous association data across diverse diseases. The flexible integration of diverse genomic, phenotypic, and interaction data further adds to the generalizability. The hypergraph approach confers versatility and adaptability by accounting for complexity and effectively harnessing key characteristics of the disease landscape - multivariate relationships, the collective influence of gene sets, and phenotype correlations - for making accurate predictions.

Performance metrics

The performance metrics employed in this study primarily focus on the accuracy of disease prediction for different values of \(K\), representing the top-K predicted genes.

As this problem is not a binary or multi-label classification, we do not have false positive (FP) or true negative (TN) counts, but only true positive (TP) and false negative (FN) counts based on whether the predicted disease set matches the ground truth. Therefore, accuracy is the most appropriate metric for this problem. Moreover, the algorithm’s ability to capture influential genes beyond the causal genes enhances its utility in real-world clinical diagnosis scenarios, allowing for accurate prediction of rare genetic diseases even when the causal gene itself is not the most influential.

Testing of the algorithm

Testing the mentioned ranking algorithm involves a multifaceted approach that encompasses various strategies to ensure its accuracy, robustness, and reliability. Majorly we have tested through a black-box testing methodology would be employed, focusing on evaluating the algorithm based solely on its input and output behavior. This would involve creating a diverse set of test cases that cover a wide range of scenarios, including normal, boundary, and exceptional cases. These test cases would be designed to assess the algorithm’s ability to correctly rank genes based on their relevance to observed phenotypic traits and disease outcomes. The mentioned algorithm tests the results against the existing dataset provided by HANRD and it compares the diseases across the ones provided given the set of symptoms. The oidDataset used in the algorithm is the mapping of diseases in our dataset to their corresponding OrphaIDs.

To give an overview of our algorithm:

Results

Prediction of causal genes was tested with all the ranking algorithms and we observed from Fig. 5 that 60% of causal genes are predicted in the top-200 genes, which is an improvement over the results of existing models like HANRD, GCN and GCAS9. The cumulative percentages are higher than the rest for all the subsequent top-K predicted genes. It is also better in terms of processing speeds, taking only two minutes compared to the time-consuming GCN and GCAS algorithms9 which involve the propagation of node embeddings over multiple epochs.

Ablation study

Weighted gene-based disease ranking

Weighted gene-based disease ranking and phenotype-based gene ranking independently perform poorly across all test cases tried with Top-K predicted genes with K ranging from 1 to 20. For Weighted gene-based disease ranking, when the results of using Phenolyzer42 and DISEASE database for calculating gene-disease association score were compared, Phenolyzer42 outperformed DISEASE. In all subsequent approaches that use gene-disease association, only the Phenolyzer42 database was utilized.

Gene-based disease ranking

Gene-based disease ranking gives an accuracy of 89.81%. The predicted genes range from a length of 1 to 1062 and the predicted diseases range from a length of 263 to 4079. From Fig. 6 we find that 50% of the causal genes are captured in Top-10 predicted genes which is again an improvement over all existing techniques by a large margin. 85% of the causal genes are captured in the Top-100 predicted genes. With subsequent Top-k genes, the growth is gradual, but 95% of the causal genes are captured in Top-300 predicted genes. This is better than the HANRD9 approach clearly, as the same result is captured in Top-1000 genes.

Weighted gene-based weighted disease ranking

Weighted gene-based weighted disease ranking gave similar trends of accuracy to that of the previous approach, across different Top-k genes. This can be observed in Fig. 7.

Top-3 and Top-5 follow the same trend for disease prediction length = 1500 Top-10 is in tandem with Top-3 and Top-5 till 2500 disease prediction length, and then outperforms the other two, but underperforms when compared to Top-1 Top-5 outperforms Top-1 and Top-3 till 1500 disease prediction length. From 1500 to 2700 Top-5 and Top-3 outperform Top-1. But after 2700, Top-1 outperforms Top-3 and Top-5 Top-15 follows the same trend as Top-5 across all lengths of disease predictions. Top-20 outperforms Top-3, Top-5 and Top-15. Top-20 followed the same trend as the Top-10 till 2000 and then outperformed Top-10. Top-20 outperforms Top-1 till 2750 and then underperforms concerning Top-1. In conclusion, from 500 to 2750 Top-20 performs the best, and from 2750 to 3250 Top-1 outperforms the rest. Top-3 performs the worst in the range [500, 1500] Top-1 performs the worst in the range [1500, 2700] Both Top-15 and Top-5 perform the worst in the range [2700, 3200]

Hybrid ranking

With the hybrid ranking approach, we found that the number of test cases passed (the number of diseases accurately predicted) reduces as we increase the number of genes. Top-1 gives an accuracy of 98.09%. This proves that we can capture the most influential gene which participates in the expression of the disease. This can be observed in Fig. 8. There is only one test case for which the most influential gene predicted is the causal gene itself. Taking only causal genes for the disease ranking process gives an accuracy of 82.8% accuracy. Thus our algorithm can capture influential genes apart from causal genes, allowing for accurate prediction of the resulting rare genetic disease.

As the mentioned algorithm tests the results against the existing dataset provided by HANRD9, in Table 3 and Fig. 9, we see the prediction accuracy of causal genes compared to other existing algorithms for different Top-K predicted genes.

Accumulated disease weight-based ranking

In the Accumulated Disease weight-based ranking, we see that Top-3 and Top-5 follow the same trend except in the disease prediction length of [1000, 2750] At length 1900, they show the same accuracy of 84.08%. Top-10 outperforms Top-3 and Top-1 till length 900, after which Top-3 outperforms the rest till 2750. From length 2750 to 3000 Top-1 outperforms the rest. Top-1 and Top-15 oscillate till 2100, where Top-15 outperforms Top-15 till 1450, then Top-1 begins to outperform till 1950, after which Top-15 outperforms from 1950 to 2100. From 2100 to 3200, Top-1 outperforms the rest. Top-15 and Top-20 have the same trend, where Top-20 only slightly outperforms till 2000, then they follow the same trend. From 500 to 1250, Top-15 slightly outperforms Top-10, after which Top-10 outperforms Top-15. Top-5 and Top-10 follow the same trend from 950. Till 950, Top-10 outperforms Top-5. Top-3 outperforms Top-15 till 1000, after which Top-15 outperforms Top-3, but they reach the same accuracy at 3200. These trends can be observed in Fig. 10 In conclusion, Top-20 performs the best in the range [500,1100]. Top-3 performs the best in the range [1100, 2550]. Top-1 performs the best in the range [2550, 3200]. Top-1 performs the worst in the range [500, 1400]. Top-15 performs the worst in the range [1400, 2000]. Both Top-15 and Top-20 performed the worst in [2000,3200].

The accumulated disease weight-based hybrid ranking

The Accumulated Disease weight-based Hybrid ranking approach shows the most variation in trends across K values (K in Top-k) as observed in Fig. 11 Top-3 and Top-5 follow the same trend in the range [500, 1000], after which Top-3 outperforms Top-5. Top-15 performs the best in the range [500,750]. Top-20 performs the best in the range [750, 1200]. Top-3 performs the best in the range [1200, 2200]. Top-1 performs the worst in the range [500, 1400] and Top-20 performs the worst in the range [1400,3200]. Top-1 performs the best in the range [2200, 3200].

Weighted versus hybrid gene-based disease ranking

The poor performance of weighted gene-based disease ranking and phenotype-based gene ranking across all tested scenarios raises questions about their suitability for predicting causal genes in rare genetic diseases. Our work suggests that these approaches may not provide the accuracy and reliability needed for clinical applications. The hybrid ranking approach emerges as the most effective method in our study, outperforming all other approaches. This highlights the benefits of combining different reliable data sources and algorithms to enhance predictive accuracy. Further research into the optimization and refinement of hybrid ranking methods could yield even better results.

Influence of gene count

One key observation in our study is that the accuracy of our algorithm decreases as the number of genes considered increases. This may indicate that our approach successfully identifies the most influential genes but struggles when faced with a larger pool of potential candidates. Nevertheless, even in scenarios with a larger gene pool, the algorithm maintains a high accuracy rate of 98.09% for the top-ranked gene. This reaffirms hypergraphs’, and subsequently our algorithm’s, ability to pinpoint the most influential gene associated with disease expression.

Inclusion of influential genes beyond causal genes

The algorithm’s ability to capture influential genes beyond the causal genes is a significant strength. This feature allows for the accurate prediction of rare genetic diseases, even when the causal gene itself is not the most influential. This broadens the utility of our approach in real-world clinical diagnosis scenarios.

Discussion

The results presented in the previous section demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed gene-disease association ranking algorithm and the benefits of using hypergraphs in predicting causal genes for rare genetic diseases. In this discussion, we will delve deeper into the implications and significance of these findings and address some key points mentioned in the results section.

Hypergraphs in the context of disease prediction and gene prioritization

Hypergraphs possess the capability to represent complex relationships between biological entities like genes and phenotypes, which proves valuable for performing tasks related to rare diseases. They have demonstrated effectiveness in modeling complex systems such as protein complexes and metabolic reactions. This structure enables the representation of multi-way relationships among biological entities, allowing a more comprehensive understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying diseases. Additionally, hypergraphs enable integrating heterogeneous entities like genomic, phenotypic and the disease data into a unified representation. This structure also enables us to efficiently analyse large-scale biological data such as genomic datasets with thousands of genes and millions of genetic variants and perform various tasks and provide results in a shorter time.

Computational complexity of the hypergraph representation

The ranking algorithms involve iterating through hypergraphs by visiting each hyperedge and collecting the nodes associated with each edge. The computational complexity can therefore be calculated as follows:

-

E as the number of hyperedges in the hypergraph.

-

V as the total number of nodes in the hypergraph.

-

avg_deg as the average degree of a hyperedge (i.e., the average number of nodes in each hyperedge).

We initially implemented the hypergraphs using adjacency matrix representation-

-

Iterating through hyperedges: The complexity for iterating through all hyperedges is O(E).

-

Collecting nodes: Since accessing an element in an adjacency matrix is O(1), collecting nodes from each hyperedge would be O(V) in the worst case (if we have to check all nodes).

-

Total Complexity: Considering the above two steps, the overall complexity for iterating through hypergraphs and collecting nodes would be O(E\(\times\)V).

To make the iteration more time-efficient, we chose adjacency list representation where-

-

Iterating through hyperedges: The complexity for iterating through all hyperedges is O(E).

-

Collecting nodes: In the worst case, we might need to collect all nodes from each hyperedge. So, the complexity for collecting nodes from each hyperedge would be O(avg_deg).

-

Total Complexity: Considering the above two steps, the overall complexity for iterating through hypergraphs and collecting nodes would be O(E\(\times\)avg_deg).

Considering the space complexity of adjacency matrix, it consumes more space compared to adjacency lists, especially for sparse hypergraphs. And as generally, adjacency lists are more space-efficient for sparse hypergraphs, we opted for the latter to facilitate for more optimized querying strategies.

Comparison with existing models and tools

Hypergraphs outperform existing models such as GCN9 and tools like Phenomizer10 which work on similarity scores, in terms of both prediction accuracy and processing speed. Notably, it achieves a 60% prediction rate for causal genes within the top 200 ranked genes, a significant improvement over existing models and tools. Moreover, the efficiency of using hypergraphs is highlighted by its ability to deliver the correct results in a fraction of the time compared to the computationally intensive GCN9 and related methods.

Choice of databases

The comparison between Phenolyzer42 and Disease Ontology (DO) databases for calculating gene-disease association scores showed that Phenolyzer42 consistently outperformed DO. As a result, further analysis was performed using the Phenolyzer42 database in all subsequent approaches. This emphasizes the importance of using high-quality and up-to-date data sources for accurate gene-disease association predictions.

Performance across top-K predicted genes

Hypergraphs’ performance across different values of K, representing the top-K predicted genes, showcases its efficiency and effectiveness. In particular, it captures 50% of causal genes within the top 10 predictions and 85% within the top 100 predictions. This is a significant achievement compared to other methods, as it ensures that the most relevant genes are being identified early in the ranking process.

Applications

Using hypergraphs to create a new algorithm for ranking gene-disease associations is something that has a lot of great uses. One of the places where it can be valuable is in clinical diagnostics for rare genetic diseases. What this means is that when there are few people with an illness caused by their DNA, this system could choose which genes to test first when making a diagnosis. In turn, physicians would find out which genes were responsible more quickly and accurately than before. Once they know the cause of a patient’s symptoms, doctors can begin treatment earlier on in the illness process. On the other hand, this method may also help scientists who study genetics. The other place where the method could be applicable is genetic research. This technique has the potential to determine phenotypic co-morbidities related to genes. This would enable researchers to identify functions that were previously unknown about certain regions of DNA in our body cells or tissues. It is also possible to carry out association studies using various different tool and method such as hypergraphs. Additionally, biological pathways can be viewed as hypergraphs.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Some of the limitations noted are our reliance only on genomic data which overlooks many crucial aspects of gene expression like post-transcriptional modifications, protein interactions and environmental influences. Integrating multiple omics data specifically transcriptomics in the form of RNA-Seq data and proteomics can significantly improve the performance of the algorithm. While the study provides valuable observations for researchers, translating the results for clinical practice requires a lot more modifications to the way the data is presented in the form of a result. Although the algorithms developed show promise for rare genetic disorders, its scalability to more number of common diseases requires refinement for handling the increased complexity. With respect to the computational scalability and performance of the individual algorithms, the Hybrid Ranking, weighted gene-based disease ranking and Accumulated Disease Weight based hybrid ranking on an average perform the best at 30 seconds of computational time. The other algorithms take more computational time to execute for the dataset under consideration. Using this analysis, it can be concluded that upon increasing the volume of data, the computational complexity of constructing the hypergraphs increases which also increases the time of execution. So in terms of scalability, the methodology needs more working to adapt to the dynamic variations in data size.

Conclusion

This study showcases the efficacy of employing hypergraphs alongside our gene-disease association ranking algorithm to predict causal genes for rare genetic disorders. The fusion of hypergraphs with our gene-disease association ranking algorithm has yielded substantial contributions to the field, particularly in the accurate prediction of causal genes for rare genetic disorders. By outperforming existing tools and models in terms of prediction accuracy and processing speed, our proposed method signifies a significant advancement in genetic diagnostics. The research also illustrates the potential of hypergraphs as a powerful tool for gene ranking. Further research into the optimization and refinement of hypergraph-based ranking algorithms could yield even better results.

Some of the limitations of our study include mere reliance on genomic data that overlooks key factors like post-transcriptional modifications and the effect of the environmental changes. Integrating other omics datasets could enhance the performance of the algorithms. Another limitation involves translation of findings into the medical field which requires modification of the results presented. We also aim to extend the algorithm’s scalability to adopt more common diseases apart from rare genetic disorders.

One notable aspect lies in its ability to not only pinpoint causal genes but also identify influential genes. This dual functionality holds immense potential for enhancing clinical diagnosis, allowing healthcare professionals to make more informed decisions and tailor treatments more precisely. By identifying influential genes, our method enables a deeper understanding of the underlying genetic mechanisms driving disease progression, facilitating targeted interventions and personalized medicine strategies. This not only enhances patient outcomes but also contributes to the overall efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare delivery. In conclusion, the problem of misdiagnosis in disease identification is a significant challenge with far-reaching consequences in healthcare. By leveraging hypergraphs and genomic data, our proposed approach aims to enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve patient outcomes. The potential impact of addressing this problem includes more precise treatments, reduced healthcare costs, and improved overall quality of care. Further research and collaboration are encouraged to advance these efforts and implement effective solutions in medical practice.

Future work

Looking ahead, there are a lot of opportunities for future research into these algorithms. Some of the areas include integration of multi-omics data into the hypergraph representation to capture the complete biochemical pathway of the diseases. This also calls for developing the hypergraphs to make it more scalable to incorporate the multiple omics datasets along with newer disease groups. In order to translate the current results into clinical practice, the algorithms also require a clean user interface tailored for clinicians for diagnosis and successful treatment procedures. Although our method performs well, it does not use Transformer-based models or Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) because of challenges with scalability in graph Transformers and oversmoothing in GCNs. If scalability and representation issues can be resolved, the topic might be restated as a Hyperedge Prediction Task utilizing a Hypergraph Convolutional Network or investigated using new Graph Transformer designs as a possible avenue for future research.

Data availibility

The datasets used in the study are available here - https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/V6X3CH. All test cases supporting the findings of this study are derived from - https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12920-018-0372-8 and its Supplementary Information and is available here- https://bmcmedgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12920-018-0372-8#Sec10.

Code availability

The readers can reach out to us at omicsdiseasesprediction@googlegroups.com for any queries or further information.

References

Pengelly, R. J. et al. Evaluating phenotype-driven approaches for genetic diagnoses from exomes in a clinical setting. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 13509 (2017).

Cromar, G. L., Zhao, A., Yang, A. & Parkinson, J. Hyperscape: Visualization for complex biological networks. Bioinformatics 31(20), 3390–3391 (2015).

Lugo-Martinez, J. et al. Classification in biological networks with hypergraphlet kernels. Bioinformatics 37(7), 1000–1007 (2021).

Ruan, D. et al. Exploring complex and heterogeneous correlations on hypergraph for the prediction of drug-target interactions. Patterns 2(12), 100390 (2021).

Nguyen, D. A., Nguyen, C. H., Petschner, P. & Mamitsuka, H. Sparse: A sparse hypergraph neural network for learning multiple types of latent combinations to accurately predict drug-drug interactions. Bioinformatics 38(Supplement–1), 333–341 (2022).

Klimm, F., Deane, C. M. & Reinert, G. Hypergraphs for predicting essential genes using multiprotein complex data. J. Complex Netw. 9(2), 028 (2021).

Feng, S. et al. Hypergraph models of biological networks to identify genes critical to pathogenic viral. System 8, 10 (2021).

Milano, M., Agapito, G. & Cannataro, M. Challenges and limitations of biological network analysis. BioTech 11(3), 24 (2022).

Rao, A. et al. Phenotype-driven gene prioritization for rare diseases using graph convolution on heterogeneous networks. BMC Med. Genom. 11, 1–12 (2018).

Köhler, S. et al. Clinical diagnostics in human genetics with semantic similarity searches in ontologies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85(4), 457–464 (2009).

Dragusin, R. et al. Findzebra: A search engine for rare diseases. Int. J. Med. Inform. 82(6), 528–538 (2013).

Rao, A. et al. Priori-t: A tool for rare disease gene prioritization using medline. PLoS ONE 15(4), 0231728 (2020).

Alves, R. et al. Computer-assisted initial diagnosis of rare diseases. PeerJ 4, 2211 (2016).

Rath, A. et al. Representation of rare diseases in health information systems: The orphanet approach to serve a wide range of end users. Hum. Mutat. 33(5), 803–808 (2012).

Ullah, M. Z., Aono, M. & Seddiqui, M. H. Estimating a ranked list of human genetic diseases by associating phenotype-gene with gene-disease bipartite graphs. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 6(4), 1–21 (2015).

Raychaudhuri, S. Mapping rare and common causal alleles for complex human diseases. Cell 147(1), 57–69 (2011).

Krämer, A., Shah, S., Rebres, R. A., Tang, S. & Richards, D. R. Leveraging network analytics to infer patient syndrome and identify causal genes in rare disease cases. BMC Genom. 18, 15–23 (2017).

Greene, D., Richardson, S. & Turro, E. Phenotype similarity regression for identifying the genetic determinants of rare diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98(3), 490–499 (2016).

Buphamalai, P., Kokotovic, T., Nagy, V. & Menche, J. Network analysis reveals rare disease signatures across multiple levels of biological organization. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 6306 (2021).

Godard, P. & Page, M. Pcan: Phenotype consensus analysis to support disease-gene association. BMC Bioinform. 17, 1–9 (2016).

Tan, M. et al. Genetic diagnostic yield and novel causal genes of congenital heart disease. Front. Genet. 13, 941364 (2022).

Lee, H. et al. Clinical exome sequencing for genetic identification of rare mendelian disorders. Jama 312(18), 1880–1887 (2014).

Chong, J. X. et al. Gene discovery for mendelian conditions via social networking: De novo variants in kdm1a cause developmental delay and distinctive facial features. Genetics Med. 18(8), 788–795 (2016).

Wang, J. L. et al. Tgm6 identified as a novel causative gene of spinocerebellar ataxias using exome sequencing. Brain 133(12), 3510–3518 (2010).

Smedley, D. & Robinson, P. N. Phenotype-driven strategies for exome prioritization of human mendelian disease genes. Genome Med. 7, 1–11 (2015).

Jacobsen, J. O. et al. Phenotype-driven approaches to enhance variant prioritization and diagnosis of rare disease. Hum. Mutat. 43(8), 1071–1081 (2022).

Yuan, X. et al. Evaluation of phenotype-driven gene prioritization methods for mendelian diseases. Brief. Bioinform. 23(2), 019 (2022).

Boudellioua, I., Kulmanov, M., Schofield, P. N., Gkoutos, G. V. & Hoehndorf, R. Oligopvp: Phenotype-driven analysis of individual genomic information to prioritize oligogenic disease variants. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 14681 (2018).

Trakadis, Y. J. et al. Phenovar: A phenotype-driven approach in clinical genomics for the diagnosis of polymalformative syndromes. BMC Med. Genom. 7, 1–13 (2014).

Zhao, M. et al. Phen2gene: Rapid phenotype-driven gene prioritization for rare diseases. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2(2), 032 (2020).

Pontikos, N. et al. Phenogenon: Gene to phenotype associations for rare genetic diseases. PLoS ONE 15(4), 0230587 (2020).

Smith, A. M. et al. Standard machine learning approaches outperform deep representation learning on phenotype prediction from transcriptomics data. BMC Bioinform. 21, 1–18 (2020).

Pržulj, N., Corneil, D. G. & Jurisica, I. Modeling interactome: Scale-free or geometric?. Bioinformatics 20(18), 3508–3515 (2004).

Cannataro, M., Guzzi, P. H. & Veltri, P. Impreco: Distributed prediction of protein complexes. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 26(3), 434–440 (2010).

Lotito, Q. F., Musciotto, F., Montresor, A. & Battiston, F. Higher-order motif analysis in hypergraphs. Commun. Phys. 5(1), 79 (2022).

Rafferty, J. et al. Ranking sets of morbidities using hypergraph centrality. J. Biomed. Inform. 122, 103916 (2021).

Wang, T., Xu, H., Zhang, R., Xiao, Y., Peng, J. & Shang, X. Hypergraph-based gene ontology embedding for disease gene prediction. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2424–2430. IEEE (2022).

Ibrahim, A. M. & Mohammed, M. A. A comprehensive review on advancements in artificial intelligence approaches and future perspectives for early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Math. Stat. Comput. Sci. 2, 173–182 (2024).

Ali, A. M. & Mohammed, M. A. A comprehensive review of artificial intelligence approaches in omics data processing: Evaluating progress and challenges. Int. J. Math. Stat. Comput. Sci. 2, 114–167 (2024).

Ding, F., Liu, A., Bai, C., Xu, B., Liu, X., Sang, S., Lin, H., Yang, Z., Wang, J., Kong, X., et al. Disease gene prediction based on heterogeneous probabilistic hypergraph ranking. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2021–2028. IEEE (2019).

Robinson, P. N. et al. The human phenotype ontology: A tool for annotating and analyzing human hereditary disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83(5), 610–615 (2008).

Yang, H., Robinson, P. N. & Wang, K. Phenolyzer: Phenotype-based prioritization of candidate genes for human diseases. Nat. Methods 12(9), 841–843 (2015).

Kundapuram, N., Natarajan, S., Bhaskar, N., Policharla, S.S., & Das, B. Integrated phenotypic and genomic profiles for exploring rare genetic diseases. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/V6X3CH.

Funding

The authors suggest no conflict of interest. The authors did not receive any funds, grants, or other support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N, N.K, N.B and S.S.P contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection, analysis, model construction, disease prediction, and literature search. B.D has participated in the manuscript review, literature search and design of the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Natarajan, S., Kundapuram, N., Bhaskar, N. et al. A Hypergraph powered approach to Phenotype-driven Gene Prioritization and Rare Disease Prediction. Sci Rep 15, 23780 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04428-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04428-z