Abstract

Procedural sedation is often performed by non-anesthesiologists in various settings and can lead to respiratory depression. A tool that enables early detection of respiratory compromise could not only enhance patient safety during procedural sedation, but also reduce the risk of medical liability. In this study, we aimed to develop a machine learning model that integrates detailed body composition data from patients undergoing liposuction to enhance the prediction of respiratory depression during procedural sedation. Features from bioelectrical impedance analysis, 3D body scanning, and manual measurements were extracted and used to train machine learning models. SHAP analysis, an explainable AI approach, was conducted to visually interpret feature importance. The XGBoost model, particularly when incorporating 3D body scanning data, demonstrated superior predictive performance, achieving an AUROC of 0.856 and a sensitivity of 0.805. The main predictors identified were upper abdominal volume, BMI, and age, highlighting the importance of the acquisition of detailed body composition data for assessing respiratory risks during sedation. The developed model effectively predicts the risk of respiratory depression in patients undergoing liposuction, offering a potential for personalized sedation protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Procedural sedation is widely used to alleviate pain, anxiety, and discomfort associated with medical procedures. It is administered across diverse settings by healthcare providers with varying levels of education and experience. However, sedation can lead to respiratory depression and hypoxemia, which are the most commonly reported adverse events, often due to factors such as upper airway obstruction, hypoventilation from reduced inspiratory drive, and impaired arousal response1,2,3,4,5. The risk of respiratory depression increases with the depth of sedation and is influenced by factors such as individual patient responses to sedatives and anatomical characteristics of the airway6. If not promptly managed, respiratory depression can lead to severe outcomes, including hypoxic brain injury and cardiovascular collapse4. Therefore, preoperative identification of patients at risk for respiratory depression is crucial for ensuring a safe and effective sedation environment.

Pre-sedation assessments typically include airway evaluations similar to those used in general anesthesia, such as the Mallampati classification, neck circumference, BMI, and obstructive sleep apnea index2,4,5. Research has been conducted to determine clinical predictors of respiratory depression during sedation in patients undergoing endoscopy, bronchoscopy, and various procedures in emergency department settings1,2,3,7. These studies identified risk factors generally limited to airway assessments and comorbidities, often in relatively small patient cohorts. While useful, these pre-sedation assessments typically focus on static anatomical features or broad physiological categories and may not fully capture the complex interplay of factors influencing respiratory function, particularly under the dynamic physiological changes induced by procedural sedation during spontaneous respiration. Although most studies on respiratory function have been conducted in mechanically ventilated patients, it is well known that functional residual capacity (FRC) decreases to a similar extent during deep sedation due to the cranial shift of the diaphragm8. Also, as excess adipose tissue, particularly in the truncal area, can impair respiratory mechanics and potentially increase the risk of airway obstruction under sedation. For example, abdominal adiposity promotes a cranial displacement of the diaphragm during procedural sedation, resulting in about 20% reduction in FRC and a heightened risk of airway collapse9. Besides, traditional airway assessments such as Mallampati class and STOP-BANG provide static snapshots of upper-airway patency but do not capture the cranial displacement of the diaphragm that reduces FRC during procedural sedation, an effect intensified by central adiposity. In this context, the body composition of individual parts, apart from BMI, may not only better predict respiratory dynamics, but also contribute additional insights into the occurrence of respiratory adverse events during procedural sedation.

Machine learning (ML) has been increasingly employed to develop predictive models for medical scenarios of interest10. They often outperform conventional statistical methods, particularly in managing complex high-dimensional relationships between features. ML’s ability to process high-dimensional data and identify complex, non-linear patterns makes it a powerful tool for developing predictive models that can potentially outperform traditional risk scores which are often based on linear relationships or simple aggregations of risk factors. AI has already demonstrated its value in providing precise and effective diagnostic and decision-making capabilities in areas such as cancer detection11,12. Unlike disease diagnosis, respiratory depression is particularly concerning because it is not a disease per se, but rather a condition triggered by the sedation process. This makes it a highly relevant target for AI-assisted prediction and prevention. However, to date, only limited machine learning models have been reported that specifically aim to predict sedation-induced respiratory depression in the postoperative setting. Yoon et al.13 developed a model using preoperative laboratory results, while Hadaya et al.14 employed comorbidity data to predict postoperative respiratory depression through logistic regression and XGBoost. Although preoperative laboratory values and demographic data have been widely utilized in prior research, they may not sufficiently capture individual physiologic variability. In an effort to improve predictability, our study incorporated body composition data as a potential surrogate for underlying physiologic factors that may influence a patient’s vulnerability to sedation-related respiratory depression. If respiratory depression can be predicted reliably in advance, it would not only enhance patient safety during procedural sedation but also reduce the risk of medical liability and litigation.

In this study, we hypothesize that integrating detailed body composition data such as volumes of specific body regions and muscle mass distribution into a machine learning model may enhance the prediction of respiratory depression during procedural sedation beyond conventional score. These physiologic parameters are thought to influence respiratory function through mechanisms like diaphragmatic excursion and changes in functional residual capacity. This hypothesis is grounded in the understanding that specific body composition metrics, particularly related to central adiposity and body volume, can substantially influence respiratory mechanics and compromise airway patency under the effects of sedatives. To this end, we built a clinical risk prediction model supported by machine learning to individually assess the probability of respiratory depression in outpatients undergoing procedural sedation for liposuction.

Methods

Study design and participants

We used data from patients who underwent procedural sedation between November 2020 and January 2024, specifically those who received liposuction under procedural sedation at 365mc Hospital, a specialized institution for liposuction in South Korea. Liposuction was performed on various body areas, including the abdomen, arms, thighs, and hips, typically lasting between 1 and 3 h. Standard ASA (American society of Anesthesiologists) monitoring was performed throughout the surgery. On arrival at the operating room, propofol administration was titrated to 3.0–10.0 mg/kg/h to keep Modified Ramsay Sedation sore between score 4 (appears asleep; purposeful responses to louder verbal commands than usual conversation or in response to light glabellar tap) and score 5 (asleep; sluggish purposeful responses only to loud verbal commands or strong glabellar tap). Patients who received ketamine or dexmedetomidine, either alone or in combination, for other medical reasons were excluded. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki regarding medical protocol and ethics and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea. (SEUMC IRB 2024-05-006). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, SEUMC IRB 2024-05-006 waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Assessment of respiratory depression and acquisition of medical information

To identify factors influencing respiratory depression events during procedural sedation, we analyzed specific patient demographics, respiratory depression occurrence, and vital sign monitoring information from sedation records. These records provided details of respiratory depression episode management during the procedure and were used as label data to indicate the occurrence of respiratory depression events during surgery. Respiratory depression was defined as any of the following: oxygen saturation falling below 95%, necessitating the insertion of a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal airway, or the need to cancel the surgery due to interventions such as application of a non-rebreathing mask or ambu-bagging. Detection of respiratory depression was supported by continuous monitoring using a pulse oximeter and capnograph. All monitoring equipment were regularly maintained and calibrated to ensure accuracy.

Demographic information, surgical information, and presurgical survey data were collected as variables associated with respiratory depression during procedural sedation. Also, we included body composition data from a bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) device (InBody 370s)153D body scanner and manual measurement, which is routinely performed prior to liposuction. The hospital uses two approaches to measure body shape: a 3D body scanning system and manual measurements. The 3D body scanning system measured detailed regional body dimensions. Specific features focusing on abdominal volume [e.g., Upper Abdominal Volume (UADV), Abdominal Volume (AV)] were included based on the physiological principle that increased abdominal volume can impede diaphragmatic movement and reduce FRC, effects known to be exacerbated during sedation-induced respiratory depression. Features related to the thighs and calves were also included, hypothesizing that proxies for lower limb muscle mass (e.g., thigh circumference, thigh volume), potentially related to overall physical condition or frailty, might correlate with respiratory reserve, as suggested by previous studies linking limb muscle mass to pulmonary function.

The 3D body scanning, including full-body anthropometry, obesity analysis, and body measurements, was conducted by PFS-304 made by PMT Innovation16. All procedures were conducted in a controlled operating room environment where standardized protocols were followed to ensure consistency in data collection. 3D body scanning was performed preoperatively with the patient in a standardized position to minimize variation.

Manual measurements were conducted by trained staff immediately before the procedure to ensure accuracy and reliability. Measurements using the BIA device, 3D body scanner, and tape were obtained for each liposuction procedure. We also noted that manual measurements provided additional dimensional data. Similar to 3D scanning data, these measurements of specific body parts were chosen to capture variations in regional anatomy and potential influences on respiratory function or airway patency during sedation.

Data preprocessing

We extracted the following 103 features from the data of 14,560 cases.

-

1.

Demographic information (eight features): age, sex, type of surgery, smoking and drinking habits, height, weight, and marital status.

-

2.

Surgical information (11 features): Surgery name and site details (covering 10 different areas including the thigh, arm, back, and abdomen).

-

3.

Body composition information (14 features): All features were numerical variables. Of these, three skeletal were muscle-related, three obesity-related, and three blood pressure features. In addition, BIA provided results regarding body composition, such as proteins, minerals, water, and body fat contents and physiological growth factors.

-

4.

Pre-surgical screening (11 features): Medical history questionnaires were administered before surgery. Originally, the questionnaire consisted of 17 multiple-choice questions. After splitting each choice into a binary variable, we redesigned the responses to the 81 categorical variables. These variables were filtered into 11 features using regularization techniques to prevent the inclusion of insignificant features as predictors.

-

5.

Blood test results (1 feature): The blood test results provided 17 features, including HIV Ab, HBsAg, WBC, RBC, Hgb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, HCV-Ab, AST [SGOT], ALT [SGPT], glucose, BUN, creatinine, platelet, thyroid stimulating factor (TSH), and total cholesterol levels. A significant proportion of data points were missing for most features (93.33% on average), except for TSH which had complete data. Therefore, we decided to exclude all features from the blood test results except for TSH. The exclusion of these features, while necessary due to missing data, is a potential limitation as these biomarkers could potentially influence respiratory risk factor.

-

6.

3D body scanning (18 features): Before surgery, all patients were scanned using a 3D body scanning system. Within the scanning system, patients, attired in light clothing, were positioned within a designated pod, and the camera was rotated 360° to scan the entire body. From the scanned data, the system measured 44 predefined features customized to the hospital’s requirements. We reduced the 44 features to 18 by eliminating those related to medically irrelevant body parts. These features included six abdominal-related features, which are particularly relevant due to their potential impact on diaphragm excursion and functional residual capacity under sedation; six thigh- and calf-related features; three arm-related features; and chest, epigastric, and pelvic features.

-

7.

Manual measurements (46 features): This method can be regarded as a classical approach for measuring body parts and is still used even though 3D body scanner systems have been implemented. It typically involves the use of a tape measure by the staff to capture the dimensions of each body part, especially those not assessed via the 3D scanner. This manual measurement technique is necessary not only because it is preferred by surgeons but also because it is convenient for estimating the total time and effort required for surgery.

The data used in this study were preprocessed before being used for training, validation, and testing. First, all the categorical data were transformed using a one-hot encoding scheme. For numerical data, only values within the Interquartile Range (IQR) were considered, excluding outliers. Since tape measurements were only taken from specific areas, indicator variables were used to distinguish between measured and unmeasured regions. Variables with a high proportion of missing data (> 50%) were excluded to maintain model robustness. Additionally, categorical variables were carefully encoded to avoid introducing bias and continuous variables were standardized to facilitate model training. Outlier detection was performed using a combination of statistical tests and visual inspection to ensure that extreme values did not skew the model results.

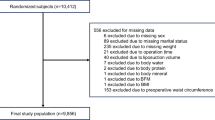

Routine laboratory parameters such as hemoglobin, electrolytes, and lipids were excluded because 93% of their values were missing in a block-wise pattern17,18. Elective outpatient liposuction rarely involves pre-operative blood testing, so these orders depended on the clinician’s judgment, and the data are considered missing not at random (MNAR). Imputing variables with more than 90% MNAR values would likely inflate variance and introduce bias19. Consequently, only TSH values, which were largely complete, were kept in the dataset. For patients undergoing multiple surgeries, the presence of respiratory depression during any single procedure was sufficient to classify the patient as having experienced respiratory depression. Of 39,985 surgical cases, the data were narrowed down to 14,560.

Training overview

In this study, we developed three models using different datasets: a full feature model, manual measurement model, and 3D scanner model. The full-feature model, which incorporated both the 3D scanner and manual measurements, served as the benchmark for maximum predictive accuracy. The 3D scanner model uses only detailed measurements from the 3D body scanner, which, while highly accurate, presents limitations owing to the high cost and technical expertise required, making it less accessible for all sedation-performing facilities. To address this issue, we created a manual measurement model that relies solely on manual measurements, offering a more cost-effective and widely applicable alternative, particularly in settings where 3D scanning is not available. This approach allowed us to compare predictive performance across datasets, balancing accuracy with feasibility in different clinical contexts.

Hyperparameter tuning for each model was performed using a grid search with cross-validation to identify the optimal settings for model performance. The training process included overfitting prevention techniques, such as early stopping and feature regularization. The models were validated using a ten-fold cross-validation approach to ensure that the results were not influenced by any particular subset of data. The training: test ratio was set to 9:1 and divided in a stratified manner.

In many previous studies that used traditional ML algorithms to predict medical outcomes, ensemble algorithms and single-method techniques, such as SVM, DT, and LR, were generally considered. In this study, we also considered both ensemble techniques and single-method machine learning techniques, such as SVM, DT, and LR, but ultimately excluded SVM and DT because of their poor performance. In the Results section, the LR was trained for comparison purposes. Generally, ensemble methods, such as Random Forest (RF) and extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithms, show superior performance compared to other studies. RF, which is a BAGGING (i.e., Bootstrap AGGregatING)-type ensemble approach, constructs multiple independent decision trees and combines their outputs for better prediction. In contrast, XGBoost, which is a boosting ensemble approach, builds decision trees sequentially and handles missing data automatically.

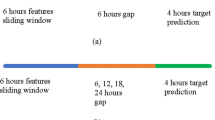

Additionally, the dataset had only 4.8% of respiratory depression cases, presenting a class imbalance issue in predicting the outcome in the training stage. Oversampling the minority class led to overfitting, whereas trimming the majority class produced a more stable model, even with ensemble methods such as Random Forest. To address this issue, we created a balanced set with a 1:1 ratio of normal to respiratory depression cases. Then, we adopted a down-sampling approach and randomly sampled normal data to match the number of patients with respiratory depression. We created 10 balanced training datasets and trained them on each dataset as shown in Fig. 1.

After 30 repetitions, the average accuracy, PPV, sensitivity, AUROC, and F1 score were calculated and compared. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a method used to interpret the output of machine learning models. It assigns each feature in the model a “SHAP value,” which indicates the contribution of that feature to the model’s prediction for a specific instance. The SHAP analysis was conducted post hoc on the trained models to quantify the contribution of each feature to the model predictions. This method was chosen because of its ability to handle complex interactions between features and provide explanations that are consistent across all models. The resulting SHAP values were used to identify key predictors of respiratory depression events and the interaction effects between the features were explored to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 14,560 patients who underwent liposuction under procedural sedation, with 91.15% (n = 13,271) used for training and validation and 8.85% (n = 1289) reserved for testing. The demographic distribution was consistent across both sets, with a mean age of approximately 35 years and a predominance of female patients (99.17% in training/validation, and 98.76% in testing). The mean BMI was slightly higher in the training set (24.70 vs. 24.58), and the distribution of BMI categories was comparable between the two groups, with most patients falling within the 18.5–25 range. The incidence of respiratory depression events was 4.80% in the training and validation sets and 4.81% in the testing set, indicating an imbalanced representation of the primary outcome across the dataset as shown in Table 1.

Model performance to predict respiratory depression

Machine learning models developed to predict respiratory depression events during procedural sedation demonstrated varying levels of effectiveness based on the datasets used as shown in Table 2. When the 3D body scanner data were included, the XGBoost model exhibited the highest performance across multiple metrics, achieving an AUROC of 0.856, indicating its superior ability to distinguish between respiratory and non-respiratory depression cases. This model also demonstrated the highest sensitivity (0.805) and precision (0.139), translating into an improved identification of true respiratory depression cases while maintaining a reasonable balance between false positives and negatives. The RF model followed closely, with an AUROC of 0.822, showed strong performance but slightly lower than that of XGBoost. Although still effective, LR lagged behind the ensemble methods with an AUROC of 0.762.

In an alternative scenario, in which manual size measurements were used instead of 3D scanner data, the performances of all models decreased slightly. XGBoost performed the best with an AUROC of 0.798, followed by RF and LR with AUROCs of 0.766 and 0.697, respectively. These results highlight the importance of body composition data for enhancing the predictive accuracy of respiratory depression during procedural sedation. When the full feature model was used, combining both the 3D scanner and manual measurements, XGBoost maintained its leading position with an AUROC of 0.839, reinforcing its robustness across different data scenarios. The RF and LR models achieved AUROCs of 0.803 and 0.734, respectively, which were consistent with the trends observed in previous analyses.

Explainability

SHAP analysis provided valuable insights into the individual contributions of each feature to the model’s predictions. The key predictors of respiratory depression included UADV, AV, BMI and age. Higher values of these features were associated with an increased likelihood of respiratory depression, suggesting that body composition and age-related factors play significant roles in respiratory complications during procedural sedation as shown in Fig. 2. Specifically, large abdominal volumes and high BMI contribute to reduced lung capacity and increased airway obstruction, whereas older age is associated with diminished respiratory muscle tone and higher sensitivity to sedatives.

In contrast, certain features were inversely related to the risk of respiratory depression. Lower thigh circumference (TC) and thigh volume (TV) were associated with a higher occurrence of respiratory depression. The surgical history on liposuction (SurgHxLTO) was also a notable predictor, where patients without such a surgical history were more likely to experience respiratory depression. Overall, the SHAP analysis shows the importance of considering a combination of body composition, respiratory function, and patient history when predicting sedation-related respiratory events as shown in Fig. 3.

Mean SHAP values for feature importance in predicting respiratory depression events. The chart displays the mean SHAP values, which quantify the average impact of each feature on the model’s predictions of events during sedation. The features are ranked in descending order of their importance, with UADV showing the highest influence on the model’s output, followed by AV, BMI, and others. Positive SHAP values indicate features that increase the likelihood of respiratory depression when their values are higher. All abbreviations in this figure are clarified in the Supplementary information.

SHAP summary plot showing the impact of features on the model’s predictions. This summary plot visualizes the distribution of SHAP values for each feature across all samples, highlighting how different values of each feature (indicated by color) influence the model’s predictions. Each point represents a SHAP value for an individual patient, with red points indicating higher feature values and blue points indicating lower feature values. The plot demonstrates that higher values of features like UADV, AV, and BMI tend to increase the risk of respiratory depression, as indicated by their positive SHAP values, while other features such as TC and TV can have a mitigating effect depending on their value. All abbreviations in this figure are clarified in the Supplementary information.

Figure 4 shows a waterfall plot for individuals who did not show respiratory depression (a) and those who showed respiratory depression during surgery (b). The waterfall plot shows the contribution of different features to the prediction of the model for each case. For the patient depicted in (a), UADV and AV are the strongest negative contributors to the event, with values of − 1.22 and − 0.89 respectively. Meanwhile, smoking had a positive contribution of + 0.53, indicating an increased risk of respiratory depression. For the patient depicted in (b), UADV was the most significant positive contributor (+ 0.87), followed by the AC (+ 0.57). This implied that higher values of these features were strongly associated with respiratory depression events in the patients. In addition, BMI showed a notable positive contribution (+ 0.51), suggesting that a higher BMI increases the risk of respiratory depression. The overall model predictions, represented by \(\:f\left(x\right)\) at the top of each plot, showed a negative value (− 3.482) for the no respiratory depression event and a positive value (3.016) for the respiratory depression event. The \(\:f\left(x\right)\) value is log odds ratio, which indicates the probability of a respiratory depressive event.

In addition to the AUROC, the trade-off between sensitivity (recall) and precision (PPV) across different threshold values was analyzed. While the XGBoost model achieved the highest AUROC, examining the precision-recall curves provided further insights into the model’s performance under various clinical scenarios. In settings where minimizing false negatives is critical, the high sensitivity of the XGBoost model may be particularly advantageous, whereas its precision may be more relevant in contexts where false positives have significant consequences as shown in Fig. 5.

Discussion

We trained a machine-learning model using patient demographic characteristics and body composition data to predict the occurrence of respiratory depression in patients undergoing procedural sedation. The model using XGBoost demonstrated an AUROC between 0.798 and 0.856 and a sensitivity close to 0.8, indicating that it could be clinically effective in predicting the possibility of sedation-related respiratory depression, which, if occurs, can lead to severe complications or life-threatening risks. Additionally, the features contributing to this model were ranked using the SHAP analysis, enabling the assessment of individual risks. Through this personalized evaluation, more tailored sedation protocols or interventions to prevent intraoperative respiratory depression can be implemented based on the preoperative screening information.

The XGBoost model consistently outperformed the other models across different datasets, particularly when 3D body-scanning data were included. An AUROC of 0.856 for the 3D scanner model underscores the importance of detailed body composition data in enhancing the accuracy of respiratory depression prediction. The high sensitivity of this model (0.8053) suggests that it is particularly useful in scenarios where the priority is to minimize false negatives, such as avoiding missed respiratory depression cases that could lead to severe complications.

The finding that BMI, age, and smoking status were factors influencing respiratory depression is consistent with previous studies2,7. Furthermore, by integrating high-resolution body-composition data, our ML model captures abdominal-mass effects that Mallampati or STOP-BANG do not include, thus providing a more comprehensive, procedure-specific risk assessment for longer cosmetic surgeries such as liposuction. In our study, the SHAP analysis further elucidated the influence of individual features on the model’s predictions, identifying UADV, AV, and BMI as the most significant predictors of respiratory depression. These findings are consistent with known physiological principles: large abdominal volumes and high BMI can mechanically impede respiration by reducing lung capacity and increasing the risk of upper airway obstruction, effects exacerbated under sedation. Moreover, our findings suggest that UADV and AV are more robust predictors of respiratory depression than demographic factors, such as BMI and older age. Also, our findings align with population studies showing that upper-body fat distribution is inversely related to lung capacity and ventilation efficiency, whereas lower-limb muscle mass that is an emerging surrogate of frailty may modulate respiratory muscle reserve20.

Although limited research is available on the changes in respiratory function during procedural sedation in patients breathing spontaneously, our results can be understood from a respiratory physiological perspective. First, a previous cross-sectional study conducted in older adults (without sedation) demonstrated negative associations between centrally distributed fat deposits and respiratory function21suggesting that patients with higher upper abdominal volumes may have lower baseline respiratory function. Additionally, the current study highlights that upper abdominal volume is a more accurate predictor than abdominal fat percentage. Procedural sedation is known to reduce tidal volume and minute ventilation and induces a cranial shift of the diaphragm, which decreases FRC. We assumed that this effect may be exacerbated in patients with higher abdominal volumes, particularly upper abdominal volumes, rather than in those with fat composition alone. Interestingly, our results demonstrate that lower TC and TV levels are associated with a higher incidence of respiratory depression. Although the mechanistic link between lower-limb volume and respiratory outcomes remains speculative, we interpret this signal in the context of sarcopenia-associated reductions in ventilatory muscle strength and recommend external validation. However, radiologically measured psoas muscle area and ultrasonography-measured quadriceps depth have been proposed as factors for assessing frailty in older patients and have been reported as predictors of intraoperative hypotension22,23. Additionally, the sum of the muscle mass from all four limbs has been shown to positively correlate with pulmonary function24. Since most studies on muscle mass and respiratory function have been conducted in older patients, further research is needed to understand how thigh volume and circumference can be used as predictors of respiratory depression during procedural sedation across a broader range of patient populations.

We also noted that the reliance on 3D body scanning data, which requires specialized and costly equipment, has practical limitations. Our data identifying abdominal volume as a major predictor of respiratory depression during procedural sedation provides evidence for extending this concept beyond the use of specific 3D body scanners, which are utilized only for certain procedures, such as liposuction. Abdominal volume data can also be obtained from patients undergoing abdominal CT, which is frequently used in clinical practice. The manual measurement model, although more accessible and cost-effective, showed reduced accuracy, with an AUROC of 0.697.

Despite these promising results, this study had several limitations. The primary limitation is the reliance on data from a single center specializing in liposuction, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other patient populations and procedures. This inherently limits the external validity and generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings, patient populations undergoing different types of procedures, or those with varying baseline health statuses and comorbidities. Also, our cohort consists primarily of young Asian women with relatively low BMI for individuals undergoing liposuction. Therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing these findings to populations with different demographic characteristics or clinical contexts.

Additionally, the study’s retrospective design, combined with the inherent class imbalance of only 4.8% of the respiratory depression cases, presents challenges in fully validating the model’s performance in a broader clinical context. Although downsampling techniques were employed to address class imbalance, the small number of respiratory depression cases could still lead to potential bias. Also, most laboratory tests were unavailable (> 90% MNAR) and therefore excluded. While this decision improved model stability in our low-risk ambulatory cohort, it may limit transportability to settings where routine pre-sedation laboratories are standard. Validation in laboratory-rich datasets is warranted.

Furthermore, the retrospective nature of the study design exposes it to potential selection biases and reliance on existing clinical documentation, which may lack granular detail on certain factors that could influence respiratory depression. While we included a wide array of variables, unmeasured confounding factors, specific to the practices and patient profile of the single center, might exist. Therefore, future research is crucial to validate our findings in prospective, multi-center studies that include a more diverse range of patient populations undergoing various types of procedures, with standardized protocols for data collection to minimize missingness and potential biases, and to confirm the generalizability of the developed models.

Data availability

Access to some or all data from this study is limited to protect patient confidentiality or due to licensing constraints. The corresponding author can, upon request, provide further details on these limitations and any requirements for obtaining portions of the data.

Abbreviations

- TBW:

-

Total body water

- PRO:

-

Protein

- MIN:

-

Minerals

- BF:

-

Body fat

- BFM:

-

Body fat mass

- BW:

-

Body weight

- HT:

-

Height

- SMFM:

-

Skeletal muscle fat mass

- SMM:

-

Skeletal muscle mass

- SMBFM:

-

Skeletal muscle body fat mass

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BFP:

-

Body fat percentage

- AFP:

-

Abdominal fat percentage

- PD:

-

Physical development

- BMR:

-

Basal metabolic rate

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- PR:

-

Pulse rate

- AMC:

-

Abdominal max circumference

- UAMC:

-

Upper abdominal max circumference

- LAMC:

-

Lower abdominal max circumference

- TC:

-

Thigh circumference

- CC:

-

Calf circumference

- AC:

-

Arm circumference

- CH_V:

-

Chest volume

- AV:

-

Abdominal volume

- UADV:

-

Upper abdominal volume

- LADV:

-

Lower abdominal volume

- TV:

-

Thigh volume

- CA_V:

-

Calf volume

- LAV:

-

Left arm volume

- RAV:

-

Right arm volume

- EV:

-

Epigastric volume

- PV:

-

Pelvic volume

- LCA_V:

-

Left calf volume

- RCA_V:

-

Right calf volume

- SurgHxLTO:

-

Surgical history (liposuction, fat grafting, others)

References

Choe, J. W., Hyun, J. J., Son, S. J. & Lee, S. H. Development of a predictive model for hypoxia due to sedatives in gastrointestinal endoscopy: a prospective clinical study in Korea. Clin. Endosc. 57, 476–485 (2024).

Cho, J. et al. Prediction of cardiopulmonary events using the STOP-Bang questionnaire in patients undergoing bronchoscopy with moderate sedation. Sci. Rep. 10, 14471 (2020).

Khan, M. T. et al. Safety of procedural sedation in emergency department settings among the adult population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intern. Emerg. Med. (2024).

Practice Guidelines for Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia 2018: A Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Dental Association, American Society of Dentist Anesthesiologists, and Society of Interventional Radiology. Anesthesiology. 128, 437–479 (2018).

Cozowicz, C. & Memtsoudis, S. G. Perioperative management of the patient with obstructive sleep apnea: A narrative review. Anesth. Analg. 132, 1231–1243 (2021).

Kang, H., Kim, D. K., Choi, Y. S., Yoo, Y. C. & Chung, H. S. Practice guidelines for Propofol sedation by non-anesthesiologists: the Korean society of anesthesiologists task force recommendations on Propofol sedation. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 69, 545–554 (2016).

Geng, W. et al. A prediction model for hypoxemia during routine sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin. (Sao Paulo). 73, e513 (2018).

Gropper, M. A. et al. Miller’s Anesthesia (Elsevier, 2020).

De Troyer, A. & Martin, J. G. Respiratory muscle tone and the control of functional residual capacity. Chest. 84, 3–4 (1983).

Shickel, B. et al. Dynamic predictions of postoperative complications from explainable, uncertainty-aware, and multi-task deep neural networks. Sci. Rep. 13, 1224 (2023).

Wani, N. A., Kumar, R. & Bedi, J. Harnessing fusion modeling for enhanced breast cancer classification through interpretable artificial intelligence and in-depth explanations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 136, 108939 (2024).

Wani, N. A., Kumar, R. & Bedi, J. DeepXplainer: An interpretable deep learning based approach for lung cancer detection using explainable artificial intelligence. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 243, 107879 (2024).

Yoon, H. K. et al. Multicentre validation of a machine learning model for predicting respiratory failure after noncardiac surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 132, 1304–1314 (2024).

Hadaya, J. et al. Machine learning-based modeling of acute respiratory failure following emergency general surgery operations. PLoS One. 17, e0267733 (2022).

InBody 370. s https://inbody.com/en/inbody/contents/view_370S.

PFS-304. https://en.pmt3d.co.kr/PFS-304.

Fischer, J. P. et al. Patterns of preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing outpatient plastic surgery procedures. Aesthetic Surg. J. 34, 133–141 (2014).

Benarroch-Gampel, J. et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann. Surg. 256, 518–528 (2012).

Chen, X. et al. Dealing with missing, imbalanced, and sparse features during the development of a prediction model for sudden death using emergency medicine data: machine learning approach. JMIR Med. Inf. 11, e38590 (2023).

Song, I., Ryu, S. & Kim, D. S. Relationship between obesity, body composition, and pulmonary function among Korean adults aged 40 years and older. Sci. Rep. 14, 19798 (2024).

Rossi, A. P. et al. Effects of body composition and adipose tissue distribution on respiratory function in elderly men and women: the health, aging, and body composition study. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 66, 801–808 (2011).

Lee, Y. Y. et al. Predictability of radiologically measured psoas muscle area for intraoperative hypotension in older adult patients undergoing femur fracture surgery. J. Clin. Med. 12 (2023).

An, S. M., Lee, H. J., Woo, J. H., Chae, J. S. & Shin, S. J. Predictive value of ultrasound-measured quadriceps depth and frailty status for hypotension in older patients undergoing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the beach chair position under general anesthesia. J. Pers. Med. 14 (2024).

Martinez-Luna, N. et al. Association between body composition, sarcopenia and pulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm. Med. 22, 106 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by 365mc Networks, whose assistance and resources were invaluable in completing this study. This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI23C0162) and an Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government(MSIT) (No. RS-2022-00155966; and Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (Ewha Womans University)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. and Y.K. participated in conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis and validation. J.K., J.W. and Y.K. were involved in introduction, methodology and writing an original draft. J.S., H.K., S.L., Y.P., J.A. and S.H. provided data and validated results. H.J. were involved in experiments and IRB administration. J.K. and J.W. contributed equally. Y.K. administered project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, JW., Woo, J.H., Seo, J. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of respiratory depression during sedation for liposuction. Sci Rep 15, 19679 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04505-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04505-3