Abstract

Lung cancer is one of the world’s deadliest cancers, often not diagnosed until it has spread beyond the lung, in part due to limitations in current medical imaging. Insufficient detail in diagnostic images can mean that patients require a biopsy to gain a full understanding of their prognosis. Here, we investigate the use of propagation-based X-ray phase-contrast imaging to capture high-resolution region-of-interest 3D Computed-Tomography (CT) images of suspicious masses, using a human chest phantom. In this study, we imaged a 3.5 cm region within the chest phantom, with each CT slice amounting to approximately 1% of the area of the whole chest at that height. X-ray energies ranging from 50 to 80 keV and propagation distances of 0 to 7 m were tested. We were able to quantify the experimental parameters that would be required to increase soft-tissue sensitivity and spatial resolution relative to conventional X-ray imaging methods, and hence improve the capacity for tumour characterisation. Our results suggest that propagation-based phase-contrast region-of-interest CT imaging could enable better tumour visualisation, which may aid in earlier detection and a better outcome for lung cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide among both men and women1. Currently, the path to diagnosis is a chest X-ray to look for obvious abnormalities, followed by a chest Computed Tomography (CT) scan or potentially Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to better understand the pathology. Currently, a clinical CT can show a tumour with a width of 1 cm or wider2, but a tumour of this size is hard to characterise with the spatial resolution of 0.5–1.0 mm typically offered by these machines. When a mass is found that is larger than 1 cm in diameter, it is common that a biopsy would be taken. Biopsies are invasive and painful and can result in recovery time for the patient. Unfortunately, the contrast and/or resolution provided by clinical CT and MRI limit early detection and tumour characterisation, often resulting in a poor prognosis for the patient3,4. Here we present a Region-of-Interest (ROI) phase-contrast CT approach that could help with non-invasive diagnosis and characterisation of lung tumours.

Phase-Contrast (PC) X-ray imaging looks at how the X-rays are refracted or how they have shifted in phase as they pass through the subject/patient to obtain more information or contrast. Some methods of phase-contrast include the use of crystals or gratings to extract phase information5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, but the approach investigated in this work utilises X-ray self-interference with propagation, also known as Propagation-Based Phase-Contrast (PB PC) imaging. In PB PC imaging, the refracted X-ray wavefield interferes with unrefracted or differently refracted X-rays as the waves propagate from the sample to the detector. This generates areas of constructive and destructive interference where the image becomes brighter and darker respectively14,15,16,17,18. These bright/dark lines are known as phase-contrast fringes. For biomedical samples or patients, the phase-contrast fringes show maximum contrast at air–tissue interfaces as their X-ray refractive properties differ significantly. As a result, heavily aerated soft tissue such as the lungs creates strong phase-contrast effects. The tiny alveoli or air sacs (typically 200 μm in diameter19) in the lungs can also be thought of as small X-ray lenses that focus the X-ray light into a speckle pattern20,21. This means that lung tissue, which appears homogenous in a conventional X-ray image, is now revealed with much more visible detail.

The use of propagation-based phase contrast also avoids the requirement for additional optics and does not require the translation of optical components as seen in other PC techniques. It is well-suited to samples of 1–2 cm in width since the pixels will be small enough to capture phase-contrast fringes, meaning the approach can be used to capture meaningful ROI images. In the work presented here, we “zoom in” to a suspicious area within the lungs and take an ROI CT, where only a fraction of the anatomy is illuminated by the X-ray beam22. We couple this with Phase-Contrast CT (PC-CT) to improve the image contrast generated by the lungs. The lungs create particularly strong refraction effects, meaning lung features that produce little contrast when observed in a conventional medical image (X-ray and CT), are now revealed with greater contrast. The ability of PC-CT to reveal the airway structures has meant the technique has been used as a research tool in small animal research studies20,23,24,25. It is also known that there is a significant radiation dose reduction afforded by phase-contrast, which is particularly beneficial for capturing images of patients26,27. In this project we extend the technique to human-scale pre-clinical models28,29,30,31 and combine it with region-of-interest CT imaging, to realise ROI PC-CT.

The challenge with region-of-interest CT, also known as interior tomography, is that the data acquired includes contrast from features that sit outside the region of interest32. Mathematical and numerical approaches have been developed in recent years to address this challenge, including iterative and AI-based approaches33,34. When reconstructing a region-of-interest CT image with a conventional CT reconstruction algorithm, we effectively assume that any part of the imaged object that rotates into and then out of the image Field-of-View (FOV) during the ROI CT scan will be ‘averaged out’ and that only the features that remain present in the projection image for the entirety of the scan will be reconstructed. However, if there is significant attenuation from parts of the sample that are outside the ROI, this will result in a bright ‘cupping’ artefact35,36 or a streak across the image in the case that a highly absorbing object (e.g. a bone) is only on one side of the ROI37. There are several approaches to address these kind of cupping artefacts with varying complexity15,38,39, and here we show the successful application of a zero-padding approach.

In this study, we explore the feasibility of propagation-based phase-contrast region-of-interest imaging of the human lung by imaging an anthropomorphic phantom at the Australian Synchrotron’s Imaging and Medical Beamline (IMBL). We tested experimental parameters such as X-ray energy and propagation distance, which were optimised using quantitative measures of image quality. The motivation for the presented study is to develop a region-of-interest phase-contrast approach for imaging a region within the lung to characterise masses < 1 cm. This could help to resolve the “watch and act” approach that so many patients are required to participate in, where a suspicious feature in X-ray images is too small for a biopsy or existing methods of imaging40. Such a technique could play a key role in diagnosing and characterising lung cancer in patients, and improve possible patient outcomes41,42,43.

Methods

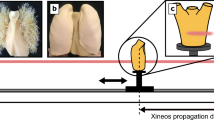

This study aims to determine the imaging settings needed for human-scale ROI lung imaging with propagation-based X-ray phase contrast. This pilot study uses a human-sized chest phantom known as “Lungman” (Kyoto Kagaku Co., Ltd), into which mock tumours of varying densities and properties can be inserted to mimic lung cancers. Here, four different X-ray energies (50, 60, 70 and 80 keV) were tested over five different sample-to-detector propagation distances (0, 1, 3, 5 and 7 m). Larger propagation distances allow the X-rays to self-interfere more, increasing the phase-contrast effects that improve the visibility of the lungs in the image (Fig. 1). CT scans of both the full chest and a region of interest were taken at each energy and distance.

Chest phantom

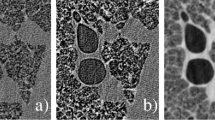

Lungman (Kyoto Kagaku Co., Ltd) is a multipurpose radiological chest phantom that has a width of 43 cm, a depth of 20 cm, a height of 48 cm and a chest girth of 94 cm. The main body comprises a urethane-based resin to mimic soft tissue and contains synthetic bones mimicking the rib cage made of modified epoxy resin, with Hounsfield units approximating the human body. The centre of the chest phantom is hollow and allows for the insertion of various lung models, including the mediastinum (heart, trachea), the pulmonary vasculature (Fig. 2A), and a foam to mimic lung soft tissue (Fig. 2B). In the results shown here, the cavity was filled with shredded neoprene to more closely mimic spongy lung soft tissue. This filling provided a range of feature sizes and densities as the neoprene is not uniform in nature, and leaves air spaces for image quality quantification44 (Fig. 2C). Lungman also comes with simulated spherical tumours with diameters 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12 mm and various Hounsfield Units (HU) with materials approx. HU-800, approx. HU-630 (both made of Urethane foam) and approx. HU-100 (made of Polyurethane, SZ50 and hydroxyapatite).

(A) is the chest insert that mimics the pulmonary vasculature. (B) is the foam chest cavity insert that mimics the soft tissue of the lung. (C) is the shredded neoprene which was used for this study, providing a range of length scales and densities not seen in the commercial inserts shown in (A) and (B). (D) shows the placement of the simulated tumours within the chest cavity surrounded by shredded neoprene. The tumours are (a) − 800 HU at 5 mm, (b) − 630 HU at 8 mm, (c) + 100 HU at 10 mm and (d) + 100 HU at 5 mm.

Four of the simulated tumours were placed inside the chest cavity of Lungman for this experiment as seen in Fig. 2D. Three of these spherical tumours of varying density are visible in the CT slices in Figs. 3, 4 and 5. The smallest and lowest density tumour, shown in Figs. 2D, 3 and 4 with visible texture, has a Hounsfield unit value of − 800. The tumour seen in the centre of the images has a Hounsfield unit value of − 630 and the brightest or highest density (most highly attenuating) tumour has a Hounsfield unit value of + 100.

Imaging set-up

The experiment was carried out at the Imaging and Medical beamline (IMBL) at the Australian Synchrotron. The acquisition was performed using a monochromatic beam set-up in propagation-based phase-contrast modality (PBI), with various sample-to-detector distances and energies. A 0.03 s, 0.04 s, 0.11 s, and 0.2 s exposure time was used for the 50 keV, 60 keV, 70 keV, and 80 keV, respectively to avoid detector saturation and achieve similar counts per pixel at each energy. This resulted in a total approximate scan time of between 2 and 12 min, depending on the x-ray energy used. For the whole chest images used to find the ROI, images were taken using a CdTe photon-counting detector with the nominal pixel size of 75 μm, known as EIGER2 3 MW (Dectris AG, Switzerland). The ROI images were acquired at each combination of energy and propagation distance, with 3640 projections over a 182° sample rotation using a pco.edge 5.5 sCMOS detector coupled with a 25 μm thick Gadox phosphor scintillator and a Nikon lens, known as ‘Ruby’, with an effective pixel size of 18 μm45.

Pre-processing, reconstruction and post-processing

The projections were flat-field (X-ray beam-only) and dark-current (detector-only) corrected, and phase-retrieved using the Paganin et al.46 algorithm. This phase retrieval algorithm requires an input δ/β ratio, which describes the X-rays complex refractive index and given as (n = 1-δ + i β) for each of the materials. A δ/β ratio of 600, 550, 500, and 480 was respectively used for 50 keV, 60 keV, 70 keV, and 80 keV. The δ/β was calculated using an error function fitting across the tissue/air interfaces in the phase-contrast CT slices, as presented by Alloo et al.47. The phase-retrieved 2D projection images were then input into a filtered back projection algorithm, implemented in the SYRMEP Tomo Project (STP) software48, to reconstruct the 3D CT slices. CT grey levels are in units of µ, the linear attenuation coefficient. When performing ROI CT, the sample exceeds the detector field-of-view, resulting in several artefacts such as cupping, bright band artefacts in the peripheral positions, and rings. The ring artefacts were corrected using the ring removal algorithm presented in Vo et al.49, which is applied in the sinogram space prior to CT reconstruction. The “bright band” artefacts were removed by applying an over-padding to the projections, which also helped to move much of the cupping artefacts outside the sample image. To correct for the cupping, a second-order polynomial was used to flatten the intensity through the slice. This is because there is tissue outside the ROI which attenuates the beam, and this attenuation must be accounted for the CT reconstruction, leading to greater grey values towards the outside of the reconstructed slice. While this means that the reconstructed voxel grey levels are not quantitative, this is already the case for the ROI CTs, and the image quality is improved quantitatively and qualitatively by this cupping correction.

Data analysis

Contrast-to-noise ratio

To measure the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), 10 slices of the CT stack at the same flat-field grey-level across each respective energy were used. Two 100 × 100 pixel regions were extracted from each slice, one containing tissue and one containing air only. Using ImageJ50, the mean and standard deviation of the grey level in each region was measured, and the CNR evaluated by taking contrast as the difference between the mean grey level for air and tissue, and the noise as the standard deviation of the grey level for a given material (calculated and then averaged for tissue and air). The CNR reported here is the average of 10 CNR values, measured from the 10 slices. Note that x-ray flux was reduced at the top and bottom of each projection due to the shape of the synchrotron beam, hence the noise varied throughout the image stack. The middle slices of the stack had the least noise and were the brightest. In order to compare energies, slices were selected with the same incident counts or grey levels in the flat fields. Note that a calibration of the detector indicated that the air kerma across 50–70 keV varied by less than 8% for the same measured grey level, with 80 keV requiring 20% higher kerma to achieve the same grey level.

Spatial resolution (SR)

The spatial resolution was measured from an ROI within the phase-retrieved CT volume that contained only air and tissue. A series of intensity profiles perpendicular to the tissue/air interface were extracted and averaged together to produce an averaged intensity profile, using the Fileswell code51. The averaged intensity profile was differentiated and the result was then fitted with a Gaussian distribution. The full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the fitted Gaussian provided a measure of spatial resolution (SR). The intensity profiles were 40 pixels wide, providing sufficient data points to fit and extract FWHM measures of 4–12 pixels. Approximately 140 individual profiles were averaged for each measurement, depending on the size of the clear region in the images.

Image quality (Q)

To provide a measure of the overall image quality of the reconstructed images, denoted as Q, we combine the calculated CNR and SR to give Q = CNR/SR. No weighting was required for the number of counts, since this was matched across the compared images.

Results

The phase-retrieved CT images of these human-sized phantom lungs all showed clear PB PC fringes, even at the relatively high X-ray energies required to obtain sufficient transmission through the chest, and with scattering through the porous lung model. The field of view in the ROI CT scans was ~ 3.5 cm across (2500 pixels × 18 μm/pixels). The Lungman chest width was 43 cm across, meaning that < 10% of the width of the whole sample/patient was illuminated in each projection. This means the associated radiation dose was also localised. The resulting ROI CT image shows the detail of a tiny fraction of the whole sample, ~ 1%, which is of note given the substantial surrounding tissue.

Correction of ROI-associated artefacts

The resultant CT slice reconstructions, following those phase retrieval and artefact-removal methods outlined above, were significantly improved compared to a standard filtered-back-projection (FBP) approach. Figure 3 shows the progression of the reconstructions from (A) a FBP reconstruction on the raw data, (B) ring artefacts removed, but cupping artefacts remaining, (C) with the cupping artefacts corrected, and (D) the final reconstruction with all artefacts corrected and phase retrieval applied. Note that the grey levels in D are adjusted to maximise contrast within the lung space, hence the bone is only saturated in the displayed image, not the data.

A visual representation of the reconstruction of the ROI CT scans containing three simulated spherical tumours at 50 keV and 7 m. (A) shows the raw data, (B) removal of ring artefacts (C) over padding applied to remove cupping and (D) the final reconstruction with ring removal, phase retrieval and over padding applied. The contrast is scaled differently for each panel to show relevant details.

Region-of-interest images

The data gathered in this study included full chest CT data captured with an Eiger detector and ROI CT data captured with a Ruby detector, allowing us to show the position of the region-of-interest relative to the whole lung, provided in Fig. 4. The tumours were placed towards the centre of the lung, a location chosen in order to include air, tissue, bone and neoprene to mimic surrounding lung tissue.

X-ray energy and propagation distance optimisation

To optimise each X-ray energy and propagation distance combination for our application, we quantified the image quality for each reconstructed region-of-interest CT as seen in Fig. 6. using the CNR, SR and Q metrics. The CNR metric indicates that an energy of 50 keV and a propagation distance of 7 m provided the greatest contrast-to-noise ratio, while an energy of 80 keV and 0 m propagation distance provided the noisiest image relative to contrast, i.e., the lowest CNR. This is seen in Fig. 5, where the lower X-ray energies show increased contrast (note that all of the images are shown on the same linear greyscale colourmap with equal minimum and maximum values), and the addition of phase contrast and phase retrieval reduced the noise at increased propagation distances.

The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), spatial resolution (SR, given in pixels) and image quality (Q) values for each energy (50, 60, 70 and 80 keV) and each propagation distance (0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 m). The values and colour gradient indicate the image quality at each energy and distance. The higher the number or the darker the colour green indicates a higher image quality, and the lower the value or the more red, the poorer the image quality.

At the largest propagation distances, the available spatial resolution was compromised by both source-size-blurring and ‘too much’ phase contrast. Source-size blurring increases with propagation distance, exceeding 1 pixel on the Ruby detector after three metres of propagation, resulting in worse spatial resolution at large propagation distances. X-ray phase-contrast fringes increase in contrast and width with increased propagation distance and lower X-ray energy, and the associated phase retrieval filter will increase in strength with increased propagation distance and lower X-ray energy46. This means that fine sample features, particularly those smaller than the fringe width or the phase-retrieval filter, were lost at large propagation distances.

When assessing the spatial resolution, it was seen that 50 keV with a propagation distance of 7 m gave a visibly blurrier phase-retrieved reconstruction than the 80 keV data with no propagation distance. This is best seen in Fig. 7 when looking at the lowest density simulated tumour phantom (the sphere closest to the centre of the image), since there are clear variations in how well the pores within that sphere are resolved. For the optimal set-up, we measured a spatial resolution of 6.57 pixels or 118 microns FWHM.

A grid of zoomed and cropped region-of-interest images from each energy (50, 60, 70 and 80 keV) and each propagation distance (0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 m), all with independent auto-scaled brightness/contrast that demonstrate the spatial resolution of the images. The dimension of each of these individual images is 10.49 mm2.

Balancing contrast, noise and spatial resolution, the image quality metric shows that an energy of 70 keV and a propagation distance of 5 m was the optimum combination. This was closely followed by 70 keV and 3 m, as seen in Figs. 6 and 7.

Dose considerations for region-of-interest imaging

To provide some idea of the change in absorbed dose when the X-ray beam is narrowed to only illuminate the region of interest, Monte Carlo dose simulations were performed. Using a segmented model of Lungman with voxel size 0.377 mm and with assigned mass densities of 1.92 g/cm3 for bone, 1.06 g/cm3 for soft tissue, and 0.26 g/cm3 for inflated lung tissue, in-house CSIRO code was used to determine the ratios of the mean absorbed dose to incident air Kerma, for each tissue, and under three illumination approaches. These approaches were (i) uniform illumination of the entire Lungman, (ii) full-width finite-height (3 cm) illumination (e.g. performed to localise the in-plane position for a region-of-interest scan), and (iii) region-of-interest illumination of an area 3.5 cm (H) by 3 cm (V). As seen in Fig. 8, the dose is localised in the case of the region of interest scan. The corresponding ratios of the mean absorbed dose to the incident air kerma are given in Table 1 below. These results show that the mean absorbed dose/incident air kerma for the thin-beam CT (scenario ii) is 13% of the whole-lung CT dose (i) and for the region-of-interest CT (iii) is only 2% of the whole-lung CT dose.

Calculated mean absorbed dose/incident air Kerma for 70 keV illumination of Lungman for (a) Region-of-interest CT of the region examined in this experiment (scenario iii) in the main text) and (b) a thin-beam CT of the chest of Lungman (scenario ii) in the main text). Note that scenario (i) is not shown since it is visually similar to scenario ii.

Discussion

Lungman was a useful phantom for the investigation of human-sized chest imaging using propagation-based phase contrast. Instead of using the standard inserts for Lungman, we opted to fill the chest cavity with shredded neoprene to better mimic the heterogenous soft tissue of the lung. It is worth noting that the phantom is designed for conventional imaging with larger pixels and hence the low-density − 800 HU tumour is likely designed to achieve the desired average attenuation, and the porous sponge-like structures required to reach such low attenuation are only resolved here due to the high spatial resolution that can be achieved using synchrotron-based local tomography. Due to this resolution, it is likely that this tumour material is of a greater density than typically displayed as − 800 HU.

Human lung tissue ranges from − 950 to − 400 HU52,53 and it is seen in the ROI CT images that the neoprene closely mimics the HU’s of human lung tissue, since the grey level matches the surrounding chest44. The tumours with HU of − 630 and − 800 have very similar HU of the mimicked lung tissue and recorded values for real human lung tissue, but both were still easily visible due to phase contrast and phase retrieval leading to a high CNR. More importantly, the texture of the tumour was clearly visible, and in a clinical setting this is important for characterising what kind of tumour is present and for forming a treatment plan.

ROI CT of such a small portion of the sample (e.g. 1%) has not yet seen clinical uptake nor been widely adopted at synchrotron sources. Previous ROI approaches, for example, where the scan field-of-view is reduced in a clinical scanner54, have reduced the slice area by a factor closer to 50%. A key assumption in our ROI CT approach is that all of the features outside of the FOV will move in and out of the region and be ‘averaged’ out. In reality, the image collected has a large cupping artefact (Fig. 3A,B), formed as a result of all of the attenuation from surrounding tissue outside of the FOV. This cupping obstructs a large portion of the ROI image (almost half the view) that was only 3.5 cm wide.

A straightforward approach to mitigate these artefacts is the so-called over-padding technique. This method involves adding zeros to each side of the projections (specifically, 25% of the FOV for the STP software), effectively simulating a larger detector. However, no additional information is introduced, as the added values are zeros, and the line integral remains unchanged. By doing so, when FBP back-projects the information, the white ring artefact is shifted farther away from the centre. Future work could either utilise an existing full-lung CT scan to predict and hence remove the expected cupping, or utilise a more advanced ROI-specific reconstruction method33,34,55.

Another challenge encountered was ring artefacts, which are a direct result of pixel-to-pixel variability in the sensitivity of the detector. A low-sensitivity pixel then tracks the rotation of the specimen in 3D and creates a ring in the reconstructed slice, with a diameter equal to the distance from the pixel at the centre of rotation. In the case where the attenuation by the sample is much larger than the attenuation from the ROI of the sample, the flat-field images used to correct for pixel-to-pixel variability are taken at a very different grey level to that seen in the sample scan. If the pixel response is non-linear, this means that such ROI scans are particularly vulnerable to ring artefacts. This could be somewhat alleviated in future studies by taking flat-field images at a reduced exposure time to match the scan images. There are several approaches to address such artefacts, which can be divided into two groups depending on whether the corrections are applied in the sinogram domain (pre-processing) or in the reconstructed slice domain (post-processing). In our study, we chose a pre-processing ring removal algorithm that operates in the sinogram domain. This method is based on a well-known Python library called Algotom56. The approach involves identifying the stripe artefacts in the sinograms stripes using a Fourier Transform-based filtering technique, correcting them by adjusting their intensity to match that of the neighbouring pixels, and finally reintegrating the corrected data back into the sinogram domain.

Imaging the phantom of a human chest using phase-contrast CT has proven the feasibility of imaging region-of-interest soft tissue (lung) with surrounding bone (rib cage) in such close proximity. Note however, that the presence of a bone may cause artefacts that may interfere with the soft tissue imaging if that bone is partially inside or close to the ROI. As seen in Fig. 5, there were some variations in the grey level of the soft tissue near the bone, particularly at lower X-ray energies.

The image quality metric Q tells us that an energy of 70 keV and a distance of 5 m is optimal for ROI PC-CT imaging of the human chest at the Australian Synchrotron’s IMBL. This is closely followed by an energy of 70 keV and a distance of 3 m with a value of 2.9. This provides some flexibility in the propagation distance choice, since these images are of similar quality.

The images taken at 0 m had the worst image quality, which was expected as the 0 m images represent attenuation images. It is expected that images captured closer to the detector have higher contributions from Compton scattering, which can reduce contrast and spatial resolution. Note however the spatial resolution measured at 0 m propagation was actually the highest of all the data sets, and the contrast between air and the soft tissue parts of Lungman remained constant across the range of tested propagation distances. Our results demonstrate that propagation-based imaging can significantly increase the contrast-to-noise ratio of region-of-interest lung CT images27. It is worth noting that trying to measure spatial resolution at 0 m was very difficult due to the high noise level57, and was only achieved after some averaging across multiple profiles. Spatial resolution was best at high energies and low energies, where phase contrast was present.

Both the image quality values (Fig. 6) and the spatial resolution (Fig. 7) suggest that using a propagation distance of 3 m, 5–7 m is beneficial to gain better visualisation of the ROI image and its contents. According to the image quality metric, the energies with the best overall result were 70 keV and 80 keV.

Interestingly, for all energies, 5 m of propagation produced the greatest image quality. This was likely due to the phase-contrast fringes being sufficiently large at this distance to be well-resolved, and the associated phase- retrieval filter covering several pixels and hence filtering out noise effectively without significantly reducing the spatial resolution. Spatial resolution losses due to penumbral blurring reduce image quality at the larger propagation distances, as seen in Fig. 7.

It is unlikely that using energies higher than 80 keV and distances greater than 7 m in the future will be of any benefit because we see that the highest quality images are present before we reach 80 keV and before 7 m. It should also be noted, however, that although this result provides general guidance to others wishing to perform such imaging, the optimal settings are specific to the experimental set-up used here. This optimal distance may decrease if one were to use smaller pixels or if a facility were used where source-size blurring is a stronger effect. A different scintillator thickness or material within a high-resolution detector could also mean a different optimal setup.

Future directions

This dataset gave us valuable insight into the possibilities of using propagation-based phase contrast to image a human chest using high-resolution ROI PC-CT. The next steps in this research include moving from a chest phantom to large animal pre-clinical imaging. We will also determine the steps required for capturing images synchronised with breathing and/or within a breath hold, so we can demonstrate that imaging of a moving lung is feasible. A breath hold of 20 s would require the scan time used here to be reduced by a factor of 20 at the optimum energy of 70 keV. Note that the exposure times here were chosen to fill the detector dynamic range, not to minimise dose nor scan time, and ultimately a different detector would likely be chosen for clinical implementation.

With the progression of this research, there will also be a focus on patient dose. The image quality metrics shown here have a similar approach to those in Gureyev et al.58, since air kerma is consistent, but future studies could weigh the image quality metric according to the absorbed dose. The use of small pixels is typically not dose efficient, meaning the dose to the ROI is large, but the dose to the rest of the lung will be spread in a similar manner to stereotactic radiation therapy and hence most of the associated dose will be at the tumour site. The Monte Carlo dose simulation results shown in Fig. 8; Table 1 demonstrates that when the beam is narrowed to the region-of-interest the mean absorbed dose is reduced to about 2% of that for the whole-lung CT. This suggests that a smaller pixel size can be used in ROI CT than for a whole-lung CT and the required additional dose to achieve sufficient counts in these small pixels could be somewhat balanced by the dose reduction associated with a narrowed beam.

Eventually, the goal would be to move from the use of synchrotron imaging to imaging with a non-synchrotron source, which would produce a much broader spectrum of X-ray radiation, and we would expect that imaging with a mean X-ray energy of 70 keV would be likely to give similarly optimal results. A key step in advancing this approach will be a comparison with existing clinical modalities.

Conclusion

With lung cancer being one of the world’s leading killers, improving the way that patients are diagnosed using non-invasive imaging techniques is crucial. Here, we demonstrated that using propagation-based phase contrast imaging to zoom in on a suspicious region could potentially improve diagnostic information and hence a patient’s prognosis in the future. The level of spatial resolution (~ 100 microns) and soft-tissue sensitivity we can achieve using 70 keV X-ray energy and 3–5 m propagation could prove beneficial in tumour characterisation to better inform treatment planning.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author Lucy Costello.

References

WHO. Lung Cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer (2023).

Hyer, J. D. & Silvestri, G. Diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Clin. Chest Med. 21, 95–106, viii–ix. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70010-1 (2000).

Fass, L. Imaging and cancer: a review. Mol. Oncol. 2, 115–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2008.04.001 (2008).

Pulumati, A., Pulumati, A., Dwarakanath, B. S., Verma, A. & Papineni, R. V. L. Technological advancements in cancer diagnostics: improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep. (Hoboken). 6, e1764. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnr2.1764 (2023).

Davis, T. J., Gao, D., Gureyev, T. E., Stevenson, A. W. & Wilkins, S. W. Phase-contrast imaging of weakly absorbing materials using hard X-rays. Nature. 373, 595–598. https://doi.org/10.1038/373595a0 (1995).

Ingal, V. N. & Beliaevskaya, E. A. X-ray plane-wave topography observation of the phase contrast from a non-crystalline object. J. Phys. D. 28, 2314–2317. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/28/11/012 (1995).

Momose, A. et al. Demonstration of X-ray talbot interferometry. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 42 https://doi.org/10.1143/jjap.42.L866 (2003).

Weitkamp, T. et al. X-ray phase imaging with a grating interferometer. Opt. Express. 13, 6296–6304. https://doi.org/10.1364/opex.13.006296 (2005).

Bravin, A., Coan, P. & Suortti, P. X-ray phase-contrast imaging: from pre-clinical applications towards clinics. Phys. Med. Biol. 58 (35), R1. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/58/1/R1 (2013).

Coan, P., Bravin, A. & Tromba, G. Phase-contrast x-ray imaging of the breast: recent developments towards clinics. J. Phys. D. 46 https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/46/49/494007 (2013).

Olivo, A. & Castelli, E. X-ray phase contrast imaging: from synchrotrons to conventional sources. Rivista Del. Nuovo Cimento. 37, 467–508. https://doi.org/10.1393/ncr/i2014-10104-8 (2014).

Baran, P. et al. Optimization of propagation-based x-ray phase-contrast tomography for breast cancer imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 62, 2315–2332. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/aa5d3d (2017).

Endrizzi, M. X-ray phase-contrast imaging. Nuclear instruments and methods in physics research section A: accelerators, spectrometers. Detectors Assoc. Equip. 878, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.07.036 (2018).

Cloetens, P., Barrett, R., Baruchel, J., Guigay, J. P. & Schlenker, M. Phase objects in synchrotron radiation hard X-ray imaging. J. Phys. D. 29, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/29/1/023 (1996).

Gureyev, T. E., Nesterets, Y. I. & Mayo, S. C. Quantitative quasi-local tomography using absorption and phase contrast. Opt. Commun. 280, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2007.08.007 (2007).

Wilkins, S. W., Gureyev, T. E., Gao, D., Pogany, A. & Stevenson, A. W. Phase-contrast imaging using polychromatic hard X-rays. Nature 384, 335–338. https://doi.org/10.1038/384335a0 (1996).

Wilkins, S. W. et al. On the evolution and relative merits of hard X-ray phase-contrast imaging methods. Philos. Trans. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 372 https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2013.0021 (2014).

Zhou, S. A. & Brahme, A. Development of phase-contrast X-ray imaging techniques and potential medical applications. Phys. Med. 24, 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2008.05.006 (2008).

Ochs, M. et al. The number of alveoli in the human lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200308-1107OC (2004).

Yagi, N., Suzuki, Y., Umetani, K., Kohmura, Y. & Yamasaki, K. Refraction-enhanced X-ray imaging of mouse lung using synchrotron radiation source. Med. Phys. 26, 2190–2193. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.598735 (1999).

Kitchen, M. J. et al. On the origin of speckle in X-ray phase contrast images of lung tissue. Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 4335–4348. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/49/18/010 (2004).

Schafer, S., Noel, P. B., Walczak, A. M. & Hoffmann, K. R. Filtered region of interest cone-beam rotational angiography. Med. Phys. 37, 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3284540 (2010).

Kitchen, M. J. et al. Dynamic measures of regional lung air volume using phase contrast X-ray imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 6065–6077. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/53/21/012 (2008).

Donnelley, M., Morgan, K. S., Siu, K. K. & Parsons, D. W. Dry deposition of pollutant and marker particles onto live mouse airway surfaces enhances monitoring of individual particle mucociliary transit behaviour. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 19, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0909049512018250 (2012).

Donnelley, M. et al. Non-invasive airway health assessment: synchrotron imaging reveals effects of rehydrating treatments on mucociliary transit in-vivo. Sci. Rep. 4 https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03689 (2014).

Nesterets, Y. I. & Gureyev, T. E. Noise propagation in x-ray phase-contrast imaging and computed tomography. J. Phys. D. 47 https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/47/10/105402 (2014).

Kitchen, M. J. et al. CT dose reduction factors in the thousands using X-ray phase contrast. Sci. Rep. 7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16264-x (2017).

Wagner, W. L. et al. Towards synchrotron phase-contrast lung imaging in patients—a proof-of-concept study on Porcine lungs in a human-scale chest Phantom. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 25, 1827–1832. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577518013401 (2018).

Haggmark, I. et al. Phase-contrast virtual chest radiography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120, e2210214120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2210214120 (2023).

Albers, J. et al. High resolution propagation-based lung imaging at clinically relevant X-ray dose levels. Sci. Rep. 13 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30870-y (2023).

Dullin, C., Wagner, W. L., Confalonieri, M. & Tromba, G. Pulmonary phase contrast CT imaging: a novel setup at the Italian synchrotron for the study of fresh lungs at human scale. Eur. Respir. J. 63 https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01604-2023 (2024).

Wang, G. & Yu, H. The meaning of interior tomography. Phys. Med. Biol. 58, R161–186. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/58/16/R161 (2013).

Arcadu, F., Marone, F. & Stampanoni, M. Fast iterative reconstruction of data in full interior tomography. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 24, 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577516015794 (2017).

Li, M. et al. Clinical Micro-CT empowered by interior tomography, robotic scanning, and deep learning. IEEE Access. 8, 229018–229032. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.3046187 (2020).

Nalcioglu, O. Mathematical aspects of NMR tomography. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 31, 983–989. https://doi.org/10.1109/tns.1984.4333422 (1984).

Chun, I. K., Cho, M. H., Lee, S. C., Cho, M. H. & Lee, S. Y. X-ray micro-tomography system for small-animal imaging with zoom-in imaging capability. Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 3889–3902. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/49/17/005 (2004).

Kyrieleis, A., Titarenko, V., Ibison, M., Connolley, T. & Withers, P. J. Region-of-interest tomography using filtered backprojection: assessing the practical limits. J. Microsc. 241, 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2818.2010.03408.x (2011).

Anastasio, M. A., Shi, D., Pan, X., Pelizzari, C. & Munro, P. A preliminary investigation of local tomography for megavoltage CT imaging. Med. Phys. 30, 2969–2980. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.1619232 (2003).

Pfeiffer, F. et al. Region-of-interest tomography for grating-based X-ray differential phase-contrast imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101 https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.168101 (2008).

Ning, J. et al. Early diagnosis of lung cancer: which is the optimal choice? Aging (Albany NY). 13, 6214–6227. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.202504 (2021).

Henschke, C. I. et al. Early lung cancer action project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 354, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6 (1999).

Midthun, D. E. Early detection of lung cancer. F1000Res 5 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7313.1 (2016).

Balata, H. et al. Early diagnosis and lung cancer screening. Clin. Oncol. (R Coll. Radiol). 34, 708–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2022.08.036 (2022).

Viermetz, M. et al. Dark-field computed tomography reaches the human scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118799119 (2022).

Hall, C. et al. Detectors for the imaging and medical beam line at the Australian synchrotron. J. Instrum. 8 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/8/06/c06011 (2013).

Paganin, D., Mayo, S. C., Gureyev, T. E., Miller, P. R. & Wilkins, S. W. Simultaneous phase and amplitude extraction from a single defocused image of a homogeneous object. J. Microsc. 206, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01010.x (2002).

Alloo, S. J. et al. Tomographic phase and attenuation extraction for a sample composed of unknown materials using X-ray propagation-based phase-contrast imaging. Opt. Lett. 47, 1945–1948. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.445802 (2022).

Brun, F. et al. SYRMEP Tomo project: a graphical user interface for customizing CT reconstruction workflows. Adv. Struct. Chem. Imaging. 3 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40679-016-0036-8 (2017).

Vo, N. T., Atwood, R. C., Drakopoulos, M. & Connolley, T. Data processing methods and data acquisition for samples larger than the field of view in parallel-beam tomography. Opt. Express. 29, 17849–17874. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.418448 (2021).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089 (2012).

Ahlers, J. N. et al. High-energy X-ray phase-contrast CT of an adult human chest phantom. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.14075 (2025).

Gattinoni, L. et al. Relationships between lung computed tomographic density, gas exchange, and PEEP in acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology 69, 824–832. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-198812000-00005 (1988).

Cressoni, M. et al. Limits of normality of quantitative thoracic CT analysis. Crit. Care. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12738 (2013).

Ma, Y. et al. Multi-instance learning based lung nodule system for assessment of CT quality after small-field-of-view reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 14 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53797-4 (2024).

Jin, S. O. et al. Dual-resolution image reconstruction for region-of-interest CT scan. J. Instrum. 9 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/9/07/c07008 (2014).

Vo, N. T., Atwood, R. C. & Drakopoulos, M. Superior techniques for eliminating ring artifacts in X-ray micro-tomography. Opt. Express. 26, 28396–28412. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.028396 (2018).

Gureyev, T. E. et al. Duality between noise and spatial resolution in linear systems. Opt. Express. 22, 9087–9094. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.22.009087 (2014).

Gureyev, T., Nesterets, Y. & de Hoog, F. Spatial resolution, signal-to-noise and information capacity of linear imaging systems. Opt. Express. 24, 17168–17182. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.017168 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Patrick Brennan and the University of Sydney for loaning the Lungman phantom. This research was undertaken on the Imaging and Medical Beamline (IMBL) at the Australian Synchrotron, part of ANSTO. We recognise scientific and technical assistance from Matthew Cameron and Anton Maksimenko and we thank the IMBL for the granted beamtime M18648 in 2022. We thank Emmanuel Brun for the suggestion of using whole-lung CT data in removing cupping artefacts. We acknowledge that this research was supported by an AINSE Ltd. Postgraduate Research Award (PGRA), an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship, and National Health and Medical Research Council (NMHRC) Synergy Grant APP2011204.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The ideas in this work were conceived by L.C., L.D., M.D., J.A., M.K. and K.M. L.C. wrote the manuscript text, with contributions from L.D., M.D., J.A., S.A., Y.N., C.H., D.H., M.K. and K.M. The experiment was performed by M.D., J.A., S.A., Y.N., C.H., D.H., M.K. and K.M. Y.N. performed dosimetry calculations. L.C. and L.D. performed the CT reconstructions, and L.C. analysed the images, with contributions from J.A. and K.M. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costello, L., Donnelley, M., Nesterets, Y. et al. Evaluating the feasibility of region-of-interest X-ray phase contrast imaging for lung cancer diagnostics. Sci Rep 15, 19881 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04509-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04509-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

High-energy X-ray phase-contrast CT of an adult human chest phantom

Scientific Reports (2025)