Abstract

New developments in perovskite-type N(CH3)4MnCl3 single crystals were examined, with a focus on their high-temperature phases. The phase transition temperature (TC) was established as being 390 K via differential scanning calorimetry and powder X-ray diffraction analyses. At 300 K, the single-crystal structure has hexagonal symmetry and exhibits thermal stability up to a high temperature of approximately 680 K. Additionally, 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) chemical shifts displayed continuous changes with temperature, without any anomalous behavior observed near TC. The 1H spin–lattice relaxation time, which represents the molecular motion of 1H, shows slight changes near TC. The phase transition from phase I to I (′), associated with changes in the rotational degrees of freedom of N(CH3)4+ molecules, is considered second-order. The small change between phases I and I (′) is consistent with a change in the space group in the same hexagonal structure previously reported. These physical properties indicate the potential applications of N(CH3)4MnCl3 as an organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal–organic hybrids, comprising both organic and inorganic components, have recently garnered considerable attention owing to their potential for customizing functionalities and physical properties, including electrical, magnetic, and optical characteristics. Among these, hybrid organic–inorganic compounds based on perovskite ABX3 and A2BX4 structures represent an intriguing class of materials1,2,3,4. Notable examples include methylammonium lead halides, which have found applications in perovskite solar cells, light-emitting diodes, lasers, and photodetectors5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. These crystals have been the focus of extensive scientific research, owing to the complex sequences of their structural phase transitions.

Numerous studies on organic–inorganic hybrid ABX3 compounds have yielded valuable insights, owing to their broad applicability. Notably, recent efforts have focused on the development of materials with ABX3 stoichiometry, where A represents a large organic cation (A = N(CH3)4+, NH3CH3+, NH2(CH3)2+, or NH(CH3)3+), B denotes a small metal cation (B = Co, Zn, Cu, Mn, or Cd), and X represents a halide anion (X = Cl, Br, or I) for highly efficient photovoltaic applications at reduced costs. One of them, tetramethyl-ammonium trihalogenometallic materials, which have the chemical formula N(CH3)4BX3 are one-dimensional magnetic compounds, and various investigations, both experimental and theoretical, have been conducted with respect to their magnetic properties and phase transitions15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

Tetramethylammonium manganese chloride N(CH3)4MnCl3 exhibits a weakly first-order ferroelastic structural phase transition at TC = 126 K37 from a high-temperature hexagonal phase I, where the N(CH3)4+ groups are orientationally disordered, to a low-temperature monoclinic phase II38. The structure of phase II is monoclinic P21/b with a = 8.811 Å, b = 13.265 Å, c = 6.460 Å, β = 99.18°, and Z = 439,40. At phase I, N(CH3)4MnCl3 compounds crystallize in the hexagonal P63/m structure with lattice constants a = b = 9.151 Å, c = 6.494 Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°, and Z = 241. The crystal comprises linear chains of face-sharing MnCl6 octahedra, along the c-axis, separated by N(CH3)4+ molecules. At room temperature, two N(CH3)4+ molecules occur per unit cell disordered about a threefold axis parallel to the c-axis. In addition, the phase I structure transforms to a prototypic structure of P63/mmc at 389 K42. The existence of a new high-temperature phase was established, namely, phase I (′) with space group P63/mmc and Z = 2. The room temperature phase I structure derives from I (′) by rotation of the octahedra chains about the c-axis; additionally, orientational disorder of the N(CH3)4+ in phase I was described. Phase II is derived from phase I by anti-phase transitional displacements of the octahedral chains along the c-axis43.

Reports abound on N(CH3)4MnCl3, which is acknowledged as a one-dimensional magnetic material. In particular, the reports describe experimental and theoretical investigations near low phase transition temperatures of the phase transition phenomena43,44,45,46,47 using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses37,42, neutron scattering measurements38,48, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analyses49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, specific heat calculations59,60,61,62, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies63,64,65,66,67,68, and dielectric properties42,69. However, little research has been conducted on the phase transition phenomenon that occurs at high temperatures of approximately 390 K.

In this study, N(CH3)4MnCl3 single crystals were grown, and their structures determined via XRD experiments on a single crystal at 300 K. The phase transition temperature at elevated temperatures was confirmed by differential scanning calorimetry and XRD experiments on the powder. Herein, a brief discussion is provided to understand the thermal properties. In studying phase transition behaviour, NMR study is a valuable tool for obtaining dynamic information about the phase transitions. To explore the influence of N(CH3)4 ions in proximity to phases I and I (′), we assessed the temperature dependences of NMR chemical shifts and line widths for both 1H and 13C. Additionally, we discuss energy transfer via the NMR spin–lattice relaxation time, which is related to the contribution of N(CH3)4+.

Methods

Crystal growth

High-quality single crystals of N(CH3)4MnCl3 were grown from a supersaturated solution using slow evaporation. This was achieved by dissolving N(CH3)4Cl (Aldrich, 98%) and MnCl2 (Aldrich, 99.9%) in distilled water in a 1:1 molecular ratio. The mixture was stirred and heated to achieve saturation. High-quality transparent single crystals were grown via gradual evaporation over several weeks in a constant-temperature bath maintained at 300 K. These crystals formed long rod shapes with dimensions of 10 mm × 3 mm × 2 mm. The crystals were stored in a desiccator to prevent moisture-related degradation.

Characterization

DSC measurements were performed using a TA Instruments DSC (Model 25) with temperature increasing and decreasing rates of 10 °C/min over a temperature range between 200 and 570 K under a dry nitrogen gas flow. The crystal morphology was observed using an optical polarizing microscope to monitor temperature variations. In addition, TG analysis was performed at an increasing rate of 10 °C/min, over a temperature range between 300 and 973 K under a nitrogen atmosphere.

The structure and lattice constants at 300 K were obtained via single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) experiments conducted at the Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSI) of the Seoul Western Centre. A single crystal was mounted on a Bruker SMART CCD diffractometer, utilizing graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα radiation and a nitrogen cold stream at − 50 °C. Data collection and integration were performed using the SMART APEX3 and SAINT software, and absorption corrections were applied using the multiscan method implemented in SADABS. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined using full-matrix least squares on F2 using the SHELXTL program70. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms were positioned at their idealized geometric locations. And, powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were measured near TC using an XRD system with the same target used in SCXRD.

NMR spectra of N(CH3)4MnCl3 were obtained using a 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) at KBSI and a 500 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) at the Laboratory of NMR, NCIRF, Seoul National University (Seoul, Korea). The 1H MAS NMR experiment was performed at a Larmor frequency of 400.13 and 500.13 MHz, respectively, whereas the 13C MAS NMR experiment was performed at a Larmor frequency of 100.61 and 125.76 MHz, respectively. Powdered samples were placed in a 4-mm CP/MAS tube. To minimize the spinning sidebands, magic-angle spinning speeds of 5 and 10 kHz were utilized. The 1H and 13C chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS) standards. The one-dimensional (1D) NMR spectra of 1H and 13C were recorded at a delay time of 0.5 s. The spin–lattice relaxation time T1ρ values for 1H and 13C were measured at delay times ranging between 200 μs to 100 ms, and the 90° pulses for 1H and 13C were set to 3.4 and 4 μs, respectively. Temperature-dependent NMR measurements were conducted between 180 and 430 K.

Experimental results

Phase transition temperature

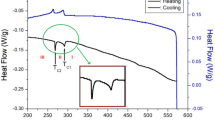

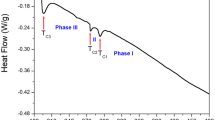

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on the N(CH3)4MnCl3 crystal at increasing and decreasing rates of 10 °C/min, utilizing a sample mass of 5.6 mg. A weak endothermic peak was detected at 390 K during the heating phase, whereas an exothermic peak was observed at 384 K during cooling, with a temperature hysteresis of 6 K between cooling and heating (Fig. 1). The enthalpy values corresponding to these transitions were 234 and 368 J/mol for heating and cooling, respectively. The discrepancies in enthalpies observed during heating and cooling suggest a second-order phase transition. Importantly, the phase transition temperatures observed during both processes were reversible. The results obtained at 390 K were in good agreement with the temperature suggested by Gesi42. The phase change occurring at this temperature was confirmed by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD); these details are discussed later in the text. The temperature range above 390 K is designated as phase I (′), while the region below 390 K is categorized as phase I. In addition, the morphologies at temperatures of (a) 300, (b) 420, (c) 500, and (d) 540 K are shown in the inset of Fig. 1 to monitor the change in the state of the single crystal with a change in temperature. Polarizing microscopy analysis indicated that the single crystal maintained its form until the temperature reached 540 K.

X-ray diffraction experiments on single crystal and powder

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) experiments were conducted on N(CH3)4MnCl3 crystals at 300 K to determine the crystal structure and lattice parameters. At phase I, the crystal structure exhibited hexagonal symmetry with the space group P63/m and lattice parameters of a = b = 9.1673 Å, c = 6.5007 Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°, Z = 2. The hexagonal structure in phase I is shown in Fig. 2. Detailed SCXRD results at 300 K are provided in Table 1, and the bond lengths and angles are presented in Table 2. The single crystal comprises N(CH3)4+ cations and MnCl64- anions, with Mn atoms surrounded by six Cl atoms. The crystal structure comprises linear chains of face-sharing MnCl64- octahedra and the organic N(CH3)4+ cations. Here, Mn(1) is surrounded by 6 Cl located at same distance apart; the Mn(1)-Cl distance is 2.5632 Å. Bond lengths for N(1)-C(1) and N(1)-C(2) are the 1.424 Å and 1.56 Å, respectively. Crystallographic data for temperature of 300 K including CIF file was deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC 2445949).

PXRD was performed on ground single-crystal samples above 300 K, over a 2θ range of 8–55° (Fig. 3). Below 390 K, the PXRD patterns (blue) remained consistent, whereas a change was observed in the patterns above 390 K (red), which correlates well with the endothermic peak observed at the same temperature as that in the DSC results. The only detectable difference in the diffraction patterns between phases I and I (′) is the disappearance of the peak near 29.72° at temperatures above 390 K. This observation aligns with result of previous reports, which indicate that although phases I and I (′) share a hexagonal crystal structure, they have different space groups. A simulated XRD pattern based on the CIF data of the crystal structure at 300 K is presented in Fig. 3, which shows excellent agreement with the experimental results. And, after observing the PXRD pattern while heating up to 500 K, the PXRD pattern.

(Navy) return to its original state with the small peak observed near 29.72° after lowering the temperature. The results of heating and cooling experiments were confirmed to be reversible by PXRD experiments. Peak indexing was performed using the Mercury software. An intense 2θ peak is observed at approximately 11°, corresponding to the (100) reflection in both the experimental and simulated patterns at 300 K. A very small peak observed near 29.72° below TC corresponds to the (102) reflection. Overall, the endothermic peak at 390 K (TC) serves as a definitive marker of the phase transition, as confirmed by PXRD analysis.

Thermodynamic properties

Thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermal analysis experiments were performed on a 5.5 mg sample over the temperature range between 300 and 873 K; the results are illustrated in Fig. 4. The morphology of the N(CH3)4MnCl3 single crystal is shown in the inset of Fig. 4; the single crystal exhibits a striking deep orange color. TG analysis indicated that the crystal exhibited thermal stability up to 680 K; however, weight loss of 2% was noted at this temperature, marking the onset of partial decomposition.

In addition, the TG curve revealed a single-stage decomposition process at higher temperatures. The remaining solid content was calculated based on molecular weight. Notably, the inflection point near 730 K in the TG curve corresponds to 50% weight loss, which is attributed to the decomposition of N(CH3)4Cl.

1H and 13C MAS NMR chemical shifts

The NMR chemical shifts of the N(CH3)4MnCl3 crystal were analyzed to understand the nature of its structural geometry near TC. The chemical shifts of 1H in N(CH3)4MnCl3 was obtained via magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR at a frequency of 400.13 and 500.13 MHz under a magnetic field of 9.4 T and 11.7 T, respectively. At 300 K, only one 1H NMR signal was detected, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. An experiment with a spinning rate of 10 kHz at a frequency of 500.13 MHz revealed a sideband distance around the 1H signal of 10 kHz (20 ppm), akin to the spinning rate. The main peaks and sidebands are indicated by arrows and crosses, respectively. This composite structure arises from the chemical distribution and anisotropy of the numerous inequivalent proton sites in the tetramethyl groups. Specifically, at room temperature, the NMR spectrum consists of a single peak at a chemical shift of 1.69 ppm, which is attributed to a methyl proton. As shown in Fig. 5b, the 1H NMR chemical shifts at a frequency of 400.13 MHz moved continuously without anomalous changes near TC as the temperature increased. In addition, the linewidth at 300 K was approximately 2.72 ppm, and remained nearly constant with increasing temperature. These findings highlight the sensitivity of NMR spectroscopy to structural changes and molecular dynamics at various temperatures, thereby providing insights into structural behavior. These occurrences confirmed that within experimental error, no changes occurred in the 1H NMR linewidths associated with phase transitions.

The chemical shifts of 13C in N(CH3)4MnCl3 were measured by 13C MAS NMR spectroscopy at a frequency of 100.61 MHz. At various temperatures, the 13C MAS NMR chemical shift (Fig. 6a) was recorded relative to TMS based on the measurements from a powder sample. The sidebands marked with “*” were spaced around the 13C signal at 10 kHz (100 ppm), consistent with the spinning rate. The 13C NMR peak (indicated by the arrow) changed more rapidly at low temperatures than at high temperatures (Fig. 6a). Figure 6b illustrates the temperature dependence of the 13C NMR chemical shifts; the 13C NMR peak shifted progressively downfield from 320 to 210 ppm as the temperature increased, with no anomalous behavior observed near TC. Additionally, the line widths of the 13C peaks decreased marginally from 2.6 to 1.9 ppm with increasing temperature, reflecting subtle changes in molecular dynamics. The line widths of the 13C peaks of phase I (´) were narrower than those of phase I, indicating that the motional averaging effects were caused by the rapid motion of the N(CH3)4 group in phase I (´), resulting from the motional narrowing caused by the rapid motion of the N(CH3)4 groups.

The spin–lattice relaxation time T1ρ values at a frequency of 400.13 MHz, which represent the extent of energy transfer around the 1H and 13C atoms of the N(CH3)4+ cation, are discussed to understand the nature of the molecular motion near TC. Thus, the intensity changes in the 1H NMR spectra, recorded at various delay times at a fixed temperature, are characterized by the decay rate of magnetization, which is governed by the T1ρ71,72,73:

where f(τ) and f(0) represent the signal intensities at time τ and τ = 0, respectively. The 1H T1ρ values for N(CH3)4MnCl3 were obtained from the linear slope of the intensity vs. delay time plot, as determined using Eq. (1). These T1ρ values could be considered as being independent of temperature, remaining constant at approximately 10 ms; however, a marginal decrease was observed above TC, as shown in Fig. 7.

Variations in the intensity of the 13C NMR spectra were monitored by extending the delay time to 300 K. The 13C T1ρ value was determined at a frequency of 125.76 MHz by modifying the spin-locking pulse sequence applied after cross-polarization (CP) preparation. Following CP, 13C magnetization was generated by proton spin-locking. The proton field was then deactivated for a variable period τ, while the 13C rf field remained active. Subsequently, the free induction decay (FID) of 13C was recorded under high-power proton decoupling and subjected to Fourier transformation. The T1ρ values were selectively extracted from the FID by conducting the experiment with various τ values. At 300 K, the 13C T1ρ value was determined from the slope of the recovery curves71,72,73,

with delay times ranging from 1 to 200 ms using Eq. (2), as shown in the inset of Fig. 7. At 300 K, the 13C T1ρ was 8.98 ms, closely matching the 1H T1ρ value. This similarity arises from bonding between 1H and 13C in the N(CH3)4+ cation, which leads to comparable relaxation times.

Conclusion

The phase transition of the perovskite N(CH3)4MnCl3 single crystals grown in this study was observed at 390 K (TC) through DSC and PXRD experiments. At 300 K, the structure exhibited hexagonal symmetry with thermodynamic stability extending up to approximately 680 K. Furthermore, the 1H chemical shifts increased with increasing temperature, while the 13C chemical shifts decreased with increasing temperature. This significant difference appears to be due to the varying strengths of the paramagnetic interactions with the unpaired electrons located at the Mn2+ ions. Brviera et al.65 reported that the 14N chemical shift and quadrupole coupling constant (νQ) display very small changes near the TC. The structural change in N(CH3)4 near TC was negligible as indicated by the 1H and 13C chemical shifts obtained in this study and the 14N chemical shifts previously reported. The N(CH3)4MnCl3 crystal has a hexagonal structure both above and below TC, and the difference lies in the space group which is P63/m in phase I and P63/mmc in phase I (′)41,42. Therefore, the phase transition from I to I (′), that may be attributed to a change in the rotational degree of freedom of the N(CH3)4+ molecules, was deemed to be second-order. In addition, the 1H NMR linewidth was independent of temperature, whereas the 13C linewidth narrowed as the temperature increased, and the molecular motion of 13C became very active at high temperatures. Additionally, the slight change in 1H T1ρ in phases I and I(‘) near TC represents the change of molecular motion.

We compared N(CH3)4CdX3 (X = Cl and Br) with the N(CH3)4MnCl3 studied here, which has the ABX3 perovskite structure. The three compounds above have phase transition temperatures at high temperature (TC = 400 K for CdCl374; TC = 390 K for CdBr375; TC = 390 K for MnCl3). And, they all have a hexagonal structure with space group P63/m below TC, whereas they have a hexagonal structure with the space group P63/mmc above TC. The room temperature phase is derived from the high temperature phase by rotating the octahedral chains about the c-axis, and the phase transition is the second-order type. The 1H T1ρ values for N(CH3)4MnCl3 were found to be of the order of ms, whereas those for N(CH3)4CdCl3 and N(CH3)4CdBr374,75 were reported to be of the order of s. The short T1ρ values are attributed to the presence of paramagnetic Mn2+ ions, with T1ρ being inversely proportional to the square of the magnetic moment of these ions71. The N(CH3)4MnCl3 is an eco-friendly candidate material that does not contain Pb, and has thermodynamic properties that are strong against moisture and temperature. Therefore, it is expected to have potential applications in various fields in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available in the CCDC 2445949.

References

Müller, K. A. & Burkard, H. SrTiO₃: An intrinsic quantum paraelectric below 4 K. Phys. Rev. B 19(7), 3593 (1979).

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(17), 6050 (2009).

Snaith, H. J. Perovskites: The emergence of a new era for low-cost, high-efficiency solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4(21), 3623 (2013).

Mitzi, D. B. Synthesis, structure, and properties of organic–inorganic perovskites and related materials. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 48, 1–121 (1999).

Ruiz-Larrea, I. et al. The specific heat of N(CH3)4MnBr3 by adiabatic calorimetry. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 11, 2259 (1999).

Zhang, M. et al. Selective valorization of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran using atmospheric O2 and MAPbBr3 perovskite under visible light. ACS Catal. 10, 14793 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. In situ synthesis of lead-free halide perovskite–COF nanocomposites as photocatalysts for photoinduced polymerization in both organic and aqueous phases. ACS Mater. 4, 464 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. Under the spotlight: The organic–inorganic hybrid halide perovskite for optoelectronic applications. Nano Today 10, 355 (2015).

Hermes, I. M. et al. Ferroelastic fngerprints in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. J. Phys. Chem. 120, 5724 (2016).

Strelcov, E. et al. CH3NH3PbI3 perovskites: Ferroelasticity revealed. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602165 (2017).

Abdel-Aal, S. K., Abdel-Rahman, A. S., Kocher Oberlehner, G. G., Ionov, A. & Mozhchil, R. Structure, optical studies of 2D hybrid perovskite for photovoltaic applications. Acta Crystallogr. A 70, C1116 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Chemical nature of ferroelastic twin domains in CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite. Nat. Mater. 17, 1013 (2018).

Mauck, C. M. et al. Inorganic cage motion dominates excited-state dynamics in 2D-layered perovskites (CxH2x+1NH3)2PbI4 (x=4–9). J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 27904 (2019).

Dahlman, C. J. et al. Dynamic motion of organic spacer cations in ruddlesden-popper lead iodide perovskites probed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Matter 33, 642 (2021).

Auerbach, R. A. & McPherson, G. L. Emission dynamics from doped crystals of (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC): Exciton trapping in a one-dimensional lattice. Phys. Rev. B 10, 6815 (1986).

White, H. W., Lee, K. H., Trainor, J., McCollum, D. C. & Holt, S. L. Specific heat of the magnetic chain TMMC below 1.2 K. AIP Conf. Proc. 18, 376 (1974).

Clement, S., Hiep, T. V. & Renard, J. P. Ultrashort proton relaxation in one-dimensional TMMC doped by diamagnetic impurities. Solid State Commun. 37, 967 (1981).

Venu, K. & Sastry, V. S. S. NMR studies of molecular dynamics in tetramethyl-lammonium tetrabromo cadmate. Chem. Phys. Lett. 122, 280 (1985).

Blakley, R. L., Martinez, C. E., Herman, M. F. & McPherson, G. L. Exciton annihilation in one-dimensional inorganic crystals: power dependent luminescence decay curves from (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC), (CH3)4NMnBr3 (TMMB) and CsMnBr3 (CMB). Chem. Phys. 146, 373 (1990).

Ivanov, B. A. & Benner, H. Internal oscillations of kink-type solitons in one-dimensional antiferromagnets like TMMC. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 11, 513 (1999).

Chen, W. W., Huang, H. C. & Kwak, S. K. Evaluation of bridge function for hard sphere fluid confined in a narrow slit-pore via TMMC mayer-sampling. Mol. Phys. 108, 1531 (2010).

Fortin, J.-Y., Durang, X. & Choi, M. Y. Limited coagulation-diffusion dynamics in inflating spaces. Eur. Phys. J. B 93, 175 (2020).

Kroon, R., Fleurent, H. & Sprik, R. Diffusion-limited exciton fusion reaction in one-dimensional tetramethylammonium manganese trichloride (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 47, 2462 (1993).

Mulla-Osman, S., Michel, D., Czapla, Z. & Hoffmann, W.-D. A nuclear magnetic resonance study of tetramethylammonium cadmium chloride (TMCC). J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10, 2465 (1998).

Lassier, B. & Brot, C. Neutron Scattering and cation rotational motion in tetra-methyllammonium manganese chloride. J. Phys. 34, 473 (1973).

Yamamoto, H., McClure, D. S., Marzzacco, C. & Waldman, M. Energy migration in a nearly one-dimensional compound, tetramethyl ammonium manganese chloride (TMMC). Chem. Phys. 22, 79 (1977).

Yamada, I. & Natsume, Y. Dynamic effect of low-symmetric distribution of spins on EPR lines in one-dimensional magnetic systems. II. Enhancement by Cu doping in TMMC. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 48, 58 (1980).

Borsa, F., Pini, M. G., Rettori, A. & Tognetti, V. Magnetic specific-heat contributions from linear vis-à-vis nonlinear excitations in the one-dimensional; antiferromagnetic (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 28, 5173 (1983).

Harada, I., Suzuki, C. & Tonegawa, T. Effect of nonmagnetic impurities on the low-temperature susceptibility of the linear antiferromagnet (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). J. Phys. Soc. Japan 49, 942 (1980).

Clement, S., Renard, J. P. & Ablart, G. The pair spectrum in diamagnetically doped TMMC. J. Mag. Reson. 60, 46 (1984).

Gonzalez, F., Lopez, R. J. & Moreno, F. Single-photon decay spectroscopy by means of a Laplace transform method: application to a crystal of TMMC. Appl. Spectrosc. 43, 324 (1989).

Knochenmuss, R. & Gudel, H. U. Exciton trapping in the one-dimensional antiferromagnet [(CH3)4N]MnCl3. J. Chem. Phys. 86, 1104 (1987).

Buijs, J. A. H. & De Jong, W. J. M. Soliton-phonon scattering in TMMC and DMMC. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 15, 6631 (1982).

Endoh, Y., Ajiro, Y., Shiba, H. & Yoshizawa, H. Resonant coupling between one- and two-magnon excitations in tetramethylamine manganese trichloride (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 30, 4074 (1984).

Wright, N. F., Johnson, M. D. & Fowler, M. Magnon-mass renormalization in (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 32, 3169 (1985).

Borsa, F. Specific-heat contribution from magnetic solitons in the linear antiferromagnet TMMC [(CH3)4NMnCl3]. Phys. Rev. B 25, 3430 (1982).

Aguirre-Zamalloa, G., Rodriguez, V., Couzi, M., Sayetat, F. & Fertey, P. Analysis of the ferroelastic phase transition of N(CH3)4MnCl3 (TMMC) by means of x-ray diffraction study. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 9, 937 (1997).

Rodriguez, V., Guillaume, F. & Couzi, M. Incoherent quasi elastic neutron-scattering study of N(CH3)4MnCl3 (TMMC). J. Phys. Chem. 100, 14109 (1996).

Morosin, B. & Graeber, E. J. Crystal structure of tetramethylammonium manganese(II) chloride. Acta Cryst. 23, 766 (1976).

Caputo, R. E. & Willett, R. D. Crystal structure and magnetic susceptibility of (CH3)2NH2MnCl3 (DMMC): A low-symmetry analog of (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 13, 3956 (1976).

Peercy, P. S., Morosin, B. & Samara, G. A. Phase transitions in (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC) and related compounds. Phys. Rev. B 8, 3378 (1973).

Gesi, K. Dielectric properties and structural phase transitions in TMMnC (N(CH3)4MnCl3) type crystals. Ferroelectrics 137, 209 (1992).

Braud, M. N. et al. Lattice dynamics and structural phase transitions in the chain compounds TMMC and TMCC: I. Structural study. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2, 8209 (1990).

Braud, M. N., Couzi, M. & Chanh, N. B. Lattice dynamics and structural phase transitions in the chain compounds TMMC and TMCC: III. Landau theory. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2, 8243 (1990).

Braud, M. N., Couzi, M., Chanh, N. B. & Gomez-Cuevas, A. Lattice dynamics and structural phase transitions in the chain compounds TMMC and TMCC: II. Raman scattering and ultrasonic measurements. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2, 8229 (1990).

Mlik, Y. & Couzi, M. On the structures of the low-temperature phases of (CH3)4NMnCl3and (CH3)4NCdCl3: A Raman scattering and group theoretical study. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 15, 6891 (1982).

Levola, T. & Laiho, R. Brillouin scattering investigation of structural phase transitions in TMMC and TMMC: Cu. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 19, 6931 (1986).

Hutchings, M. T., Pawley, G. S. & Stirling, W. G. A neutron scattering investigation of some aspects of the structural phase transition in (CD3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 16, 115 (1983).

Bourdel, D., Ruiz, F., Ablart, G. & Pescia, J. Spin relaxation in TMMC: Evidence of two paramagnetic species. Solid State Commun. 29, 727 (1979).

Bakheit, M. A., Barjhoux, Y., Ferrieu, F. & Nechtschein, M. Nuclear relaxation at high temperature in the one-dimensional paramagnetic TMMC. Solid State Commun. 15, 25 (1974).

Lagendijk, A. & Schoemaker, D. Half-field EPR transition in the one-dimensional paramagnetic tetramethylammonium-manganese-trichloride (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 16, 47 (1977).

Cheung, T. T. P., Soos, Z. G., Dietz, R. E. & Merritt, F. R. Temperature dependence of exchange narrowing in the one-dimensional antiferromagnet N(CH3)4MnCl3 (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 17, 1266 (1978).

Siegel, E. & Lagendijk, A. Anomalous frequency-dependence of the EPR linewidth in the one-dimensional paramagnet tetra-methyl-ammonium-manganese-chloride (TMMC). Solid State Commun. 32, 561 (1979).

Tuchendler, J., Magarino, J. & Renard, J. P. EPR experiments in the one-dimensional salt (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC) at temperatures between 4.2 and 70 K. Phys. Rev. B 20, 2637 (1979).

Lauer, C. & Benner, H. Influence of interchain interactions on the magic angle EPR linewidth of (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC) doped with Cu. Phys. Rev. B 24, 329 (1981).

Motokawa, M., Bockstal, L. V. & Herlach, F. Electron spin resonance of TMMC with submillimetre waves. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 18, 5009 (1985).

Natsume, Y., Sasagawa, F., Toyoda, M. & Yamada, I. Dynamic effect of low-symmetric distribution of spins on EPR lines in one-dimensional magnetic systems, I. Theory and experiment in TMMC. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 48, 50 (1980).

Allam, L., Abart, G., Pescia, J., Clement, S. & Renard, J. P. Effect of diamagnetic doping on the magnetic resonance in a quasi-one-dimensional system tetramethylammonium manganese trichloride. Phys. Rev. B 40, 8654 (1989).

Levola, T. & Kleemann, W. Magnetic specific heat and structural phase transitions in (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC) and TMMC:Cu2+ studied by crystal optica. Phys. Rev. B 32, 4697 (1985).

Dietz, R. E. et al. The specific heat of the one-dimensional antiferromagnet TMMC above 1 K. Solid State Commun. 15, 1185 (1974).

Vis, B., Chau, C. K. & Weinstock, H. Specific heat of TMMC in the region of low temperature magnetic phase transition. Solid state Commun. 15, 1765 (1974).

de Jonge, W. J. M., Swuste, C. H. W. & Kopinga, K. Specific heat of nearly-one-dimensional tetramethyl ammonium manganese trichloride (TMMC) and tetramethylammonium cadmium trichloride (TMCC). Phys. Rev. B 12, 5858 (1975).

Hone, D. & Scherer, C. Proton spin-lattice relaxation in TMMC [(CH3)4NMnCl3]. Phys. Rev. B 9, 965 (1974).

Tchao, Y. H. & Clement, S. Anisotropie du temps de relaxation des protons dans le TMMC. J. Phys. 35, 861 (1974).

Baviera, A., Bonera, G. & Borsa, F. 14N NMR study of (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). Phys. Lett. 51A, 463 (1975).

Boucher, J.-P., Ahmed Bakheit, M. & Nechtschein, M. High-temperature spin dynamics in the one-dimensional Heisenberg system (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC): Spin diffusion, intra- and interchain cut off effects. Phys. Rev. B 13, 4098 (1976).

Hone, D. & Pires, A. Symmetry crossover in the spin dynamics of (CH3)4NMnCl3 (TMMC). Phys. Rev. B 15, 323 (1977).

Holyst, J. A. & Benner, H. Nuclear spin-lattice relaxation due to soliton pairs in TMMC below TN. Solid State Commun. 72, 385 (1989).

Dupas, C. & Renard, J.-P. Effect of impurities on the Neel temperature and the low-temperature magnetic susceptibility of the quasi-one-dimensional anti-ferromagnet TMMC. Phys. Rev. B 18, 401 (1978).

SHELLXTL v6.10, Bruker AXS, Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA (2000).

Abragam, A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism (Oxford University Press, 1961).

Koenig, J. L. Spectroscopy of Polymers (Elsevier, 1999).

Harris, R. K. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (Pitman Publication, 1983).

Lim, A. R. High-temperature phase transition in N(CH3)4CdCl3 studied using static NMR and MAS NMR. Appl. Magn. Reson. 45, 9 (2014).

Lim, A. R. & Kim, S. H. NMR analysis of structural geometry and molecular dynamics in perovskite-type N(CH3)4CdBr3 crystal near high-temperature phase transition. RSC Adv. 14, 13445 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (2023R1A2C2006333).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R. Lim designed the project, NMR experiment, and wrote the manuscript. M.Y. Choi performed X-ray and TGA experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, M.Y., Lim, A.R. Structure and molecular dynamics of perovskite N(CH3)4MnCl3 crystals of high-temperature phases I and (I′). Sci Rep 15, 21297 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04582-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04582-4