Abstract

This study refines the gravity anomaly model derived from altimetry data by employing a multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network to integrate multi-source geophysical data (longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly, geoid height, bathymetry, and sediment thickness) based on shipborne gravity. To reduce the impact of land on gravity anomaly inversion, the experimental area is divided into nearshore and offshore regions, with separate inversions for each. The model is trained using differences between shipborne gravity control points and 8′×8′ grid points as input data, and differences between control point gravity anomalies and SDUST2022GRA model values as output data. The trained model predicts gravity anomalies at grid centers, and SDUST2022GRA values are applied to restore the predicted anomalies. The Gulf of Mexico region (81°W–99°W, 15°N–32°N) is selected to establish a high-resolution (1′×1′) MLP Gravity Anomaly model (MLP_GRA). Compared to the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1, and DTU21GRA models, the MLP_GRA model reduces the standard deviation (STD) and mean absolute error (MAE) by 0.4 mGal and 0.32 mGal, 0.54 mGal and 0.37 mGal, and 0.39 mGal and 0.27 mGal, respectively. These results confirm the reliability and effectiveness of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate marine gravity models are essential for geodesy, geophysics, and marine resource development. These models support research on Earth’s shape1, seafloor topography inversion2, marine resource exploration3, and satellite orbit determination4.

Shipborne gravity measurement, the most widely used technique in marine gravity surveys, provides high observation accuracy, straightforward instrument operation, and high data resolution. Modern shipborne gravimeters achieve an accuracy of approximately 1–3 mGal (1 mGal equals 10⁻⁵ m/s²)5. However, these measurements are time-consuming and costly. Obtaining global gravity data through shipborne gravity surveys remains challenging due to limited coverage, high costs, and the sparse, uneven distribution of measurement points6.

Advances in satellite altimetry technology, especially geodetic missions, have significantly enhanced the accuracy and resolution of altimetric data. Altimetry data has become a primary source for marine gravity inversion. Methods for deriving gravity anomalies from altimetry data include the inverse Stokes formula7, least squares collocation8, the Laplace equation9 and the inverse Vening-Meinesz formula10. Gravity anomaly models for both global and regional scales have been developed based on altimetry data11,12,13,14,15. Gravity anomalies derived from multiple altimeter satellites with a ground track spacing of about 2.5 km, achieve a global accuracy of 1–2 mGal16. However, boundary effects and coastal contamination of altimeter waveform data reduce the precision of inverted marine gravity in nearshore areas. Marine gravity anomalies are influenced by seafloor topography variations and crustal density changes17,18. Regions with pronounced seafloor topography variations exhibit substantial gravity anomaly changes. Consequently, regions with pronounced seafloor topography exhibit lower gravity anomaly precision when derived from altimetry data within a calculation window spanning several tens of kilometers.

Altimetry data serve as an effective complement to shipborne gravity measurements, extending the spatial coverage of marine gravity data19. Shipborne gravity data are less influenced by coastlines and seabed topography compared to gravity anomalies derived from altimetry data. Therefore, shipborne gravity can be used to enhance the accuracy of gravity anomaly models, particularly in coastal regions and areas with pronounced seafloor relief.

Deep learning, an essential branch of machine learning, utilizes multilayer neural networks to uncover complex nonlinear relationships between input and output data. Driven by advances in computational power and the proliferation of big data, deep learning has found widespread applications across various domains. Multi-channel convolutional neural networks, integrated with positional data, vertical deflections, and seafloor topography, have been successfully applied to gravity inversion20. By using the MLP neural network to integrate multi-source geodetic differential data, the accuracy of the bathymetric model in the Caribbean region has been significantly enhanced21. Compared to other deep learning methods, MLP exhibits strong nonlinear fitting capabilities, a simple, flexible structure, and robust generalization ability, enabling efficient handling of regression and classification tasks while progressively extracting and optimizing features through multiple hidden layers22. In gravity anomaly refinement studies, MLP facilitates rapid gravity anomaly prediction, enabling the fusion of multi-source geophysical data and revealing complex nonlinear relationships among gravity anomalies, seafloor topography, and crustal density—an advantage that traditional methods often fail to achieve. Recent studies have employed MLP to refine gravity anomaly models, particularly by using shipborne gravity data to improve satellite-altimetry-based gravity inversion models. This approach overcomes the limited correction radius in traditional methods23. However, this study utilized only single-source topographic data.

This study aims to refine the gravity anomaly model derived from altimetry data by using MLP to integrate differential multi-source geophysical data, based on shipborne gravity data. The differential multi-source data include differences in position, gravity anomalies, geoid height, bathymetry and sediment thickness between shipborne gravity control or prediction points and the surrounding grid points. The experimental area and related data are described in “Experimental area and data”. “Research method” covers the principles of the MLP neural network, the data organization methods and the workflow for developing the gravity anomaly model. “Establishment of gravity anomaly model” presents the construction of a gravity anomaly model for the experimental area. “Accuracy evaluation” validates the MLP_GRA model using gravity anomaly values from checkpoints and compares it with other models. The conclusion is provided in “Conclusion”.

Experimental area and data

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the study area, the gravity anomaly models employed, the geophysical datasets incorporated, and the shipborne gravity data utilized in this research. First, the Gulf of Mexico is introduced as the experimental region, emphasizing its geographical and geological characteristics. Second, the gravity anomaly models employed in the refinement process are described, including the XGM2019e_2159 model for correcting biases in shipborne gravity data, the SDUST2022GRA model as the primary input, and other global models for comparative purposes. Third, the study outlines the auxiliary geophysical datasets used for model training and prediction, including sediment thickness, mean dynamic topography, mean sea level, and bathymetric data. Finally, a detailed account is provided of the processing procedures and statistical outcomes related to the shipborne gravity data.

Experimental area

The Gulf of Mexico is a relatively compact body of water located between the United States and Mexico. The Gulf of Mexico’s coastline is rugged, and its seafloor topography is complex, featuring the Sigsbee Abyssal Plain, the Mexico Basin, the Cayman Trench and the Cayman Ridge24. Consequently, the Gulf of Mexico region (261–278°W, 15–32°N) is selected as the experimental area in this study. The deepest point in the study area reaches approximately 6700 m, located in the Cayman Trench.

Gravity anomaly model

The SDUST2022GRA25 model is a global marine gravity anomaly model developed by Shandong University of Science and Technology. A novel method was employed during its development to recover gravity anomalies from cross-track altimeter data. The model is derived from both across-track and along-track data obtained from multiple satellite altimeters.

The SIO_V32.126 model, a global gravity anomaly model released by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), is designed to provide high-accuracy gravity field information worldwide, with a particular emphasis on oceanic regions.

The DTU21GRA27 model is a global marine gravity anomaly model developed by the Technical University of Denmark. During its development, the DTU21GRA model utilized observational data from multiple satellites, ensuring comprehensive coverage an-d reliability.

The XGM2019e_215928 model is a gravity anomaly model released by the International Centre for Global Earth Models (ICGEM) in 2019. The model can be calculated from the gravity anomaly model XGM2019e. The order of the model used here is 2159.

This study takes the SDUST2022GRA model as the object for refinement. The gravity anomaly values at the shipborne gravity control points, prediction points and surrounding grid points are obtained from the SDUST2022GRA gravity anomaly model. Additionally, the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models are used to evaluate the developed gravity anomaly model. The shipborne gravity data are corrected for gross errors by using the XGM2019e_2159 model as a reference gravity field model.

Geophysical data

The sediment thickness data model employed in this study is provided by the NCEI, under the NOAA of the United States. The global sediment thickness grid, GlobSed_V329, includes new data and marine sediment thickness maps for several regions, with a grid resolution of 5′.

The DTU22MDT30 model is a geodynamic Mean Dynamic Topography model developed by the Technical University of Denmark. This model is derived using the new DTU21MSS model and has undergone a re-evaluation of filtering, thereby improving its resolution.

The CNES_CLS_2022MSS31 model was jointly released by the French Space Agency (CNES) and Collecte Localisation Satellites (CLS). This model emphasizes uniformity of the marine content and applies specific processing to geodetic mission data.

The topo_25.1 model, released by SIO in January 2023, is used in this study to acquire seafloor topography data. It has a grid resolution of 1′.

Figure 1 shows the GlobSed_V3, DTU22MDT, CNES_CLS_2022MSS, and topo_25.1 models in the Gulf of Mexico region.

Geophysical data. (a) Mean Dynamic Topography data. (b) Sediment thickness data. (c) Mean Sea Surface data. (d) Bathymetry data. (GMT v6.4.0, https://gmt-china.org/).

Shipborne gravity data

Shipborne gravity data are provided by the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States. The study area includes 28 shipborne gravity track datasets, spanning from 1961 to 1985. Long-wave system errors in the shipborne gravity data on each track are corrected using quadratic polynomial regression32. According to the “3σ” principle33, shipborne gravity points with gross errors are excluded. The process involves interpolating gravity anomalies from the XGM2019e_2159 model to the shipborne gravity points, calculating the differences between the interpolated and shipborne gravity anomalies, determining the standard deviation of these differences, and excluding points where the deviations exceed three times the standard deviation. A total of 6413 shipborne gravity points were excluded, leaving 236,432 points, corresponding to an exclusion rate of approximately 2.6%. The shipborne gravity data before and after the adjustments are shown in Table 1.

Research method

This section introduces a high-accuracy marine gravity anomaly modeling approach that leverages multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural networks in combination with the difference in multisource geophysical datasets. The content is structured into four main components. First, the architecture of the MLP neural network is outlined, and its predictive mechanism is explained. Second, the arrangement of input and output data is described, including how feature vectors are generated from spatial differences between observation sites and neighboring grid points. Third, regional segmentation of the Gulf of Mexico is performed to mitigate land-induced effects and enhance prediction accuracy. Finally, the model training pipeline is presented, covering parameter selection, the prediction workflow, and the reconstruction method, ultimately producing a refined gravity anomaly model. Together, these components form a precise and efficient methodological framework for gravity anomaly refinement.

MLP neural network

The Multi-Layer Perceptron is a representative feedforward neural network that effectively identifies patterns in complex datasets and maps relationships between input and output vectors34. The MLP consists of an input layer, multiple hidden layers and an output layer35,36. Each layer contains several nodes, are also referred to as neurons. Nodes within the same layer are not interconnected, whereas nodes in adjacent layers are fully connected. The input layer, which stores the input data, consists of the number of nodes equal to the features in the input data. The complexity and performance of the MLP model are significantly influenced by the quantity of hidden layers and nodes in each layer37. Nodes in the hidden layers apply activation functions to process inputs from the preceding layer through nonlinear transformations. The output layer, as the final layer of the MLP, is responsible for producing the ultimate prediction results.

The output y of the nodes in the hidden layer can be calculated as follows:

where \(\text{Tanh} ( \cdot )\) is the activation function, x is the input data of the node, and \({W_1}\) and \({b_1}\) represent the weight and bias, respectively.

Moving from the hidden layer to the output layer, let g represent the output of the output layer, which can be calculated as follows:

where \({W_2}\) and \({b_2}\) represent the training parameters, and n is the input data.

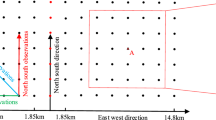

Data organization

The format of the input and output data is critical for the training of the MLP neural network, as it directly impacts the accuracy of both training and prediction. Given the strong correlation between marine gravity anomalies and variations in seafloor topography and crustal density, gravity anomalies are predicted by using the differences in multi-source geophysical data between control points or predicted points of interest and surrounding grid points. Taking into account both the computer’s performance and the experiment’s accuracy, an 8’×8’ grid is established around each shipborne gravity control point. The grid points are sequentially numbered from Grid Point 1 to Grid Point 64. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of grid points, the structure of the data organization, and the framework of the MLP neural network.

The input data sequence used for training or prediction in this study includes the differences in longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly, geoid height, bathymetry and sediment thickness between the point of interest (control or prediction point) and Grid Point 1. This sequence is followed by the corresponding differences between the point of interest and Grid Points 2 to 64, resulting in a total of 384 data points. The input data can be calculated as follows:

where i represents the i-th grid point, ip denotes the point of interest, \({L_{ip}}\) and \({B_{ip}}\) represent the longitude and latitude of the point of interest, respectively, while \(L_{{grid}}^{i}\) and \(B_{{grid}}^{i}\) represent the longitude and latitude of the i-th grid point. \(\Delta {g_{ip}}\), \({h_{ip}}\)and \({T_{ip}}\)represent the interpolated values from the SDUST2022GRA, topo_25.1 and GlobSed_V3 models at the point of interest, respectively. \(\Delta g_{{grid}}^{i}\), \(h_{{grid}}^{i}\) and \(T_{{grid}}^{i}\) represent the interpolated values of these models at the i-th grid point. \({N_{ip}}\) represents the geoid height of the point of interest, \(N_{{grid}}^{i}\) represents the geoid height at the i-th grid point, and these can be calculated as follows:

where \(MS{S_{ip}}\) and \(MD{T_{ip}}\) represent the interpolated values of the CNES_CLS_2022MSS model and the DTU22MDT model at the point of interest, \(MSS_{{grid}}^{i}\) and \(MDT_{{grid}}^{i}\) represent the interpolated values of the two models at the i-th grid point.

The training output is the difference between the shipborne gravity anomaly at the control point and the corresponding SDUST2022GRA model gravity anomaly, resulting in a single data, which can be calculated as follows:

where \(\Delta {\left( {\Delta g} \right)_{output}}\) represents the output data for training, \(\Delta {g_{train}}\) represents the shipborne gravity anomaly value at the training point, and \(\Delta {g_{SDUST2022GRA}}\) is the interpolated value from the SDUST2022GRA model at the training point.

The center of each 1′×1′ grid in the study area is selected as the point of interest for prediction. The organization of the input data for prediction follows the same sequence as that for training, specifically the differences in longitude(\(\Delta L\)), latitude(\(\Delta B\)), gravity anomaly(\(\Delta \left( {\Delta g} \right)\)), geoid height(\(\Delta N\)), bathymetry(\(\Delta h\)), and sediment thickness(\(\Delta T\)).

Marine partitioning

Prior to training the MLP model, the study area should be partitioned. In areas within 4′ of the coastline, grid points from control and check points may fall on land. To minimize the influence of land on the accuracy of gravity inversion, the Gulf of Mexico is divided into two sub-regions: Area A, located within approximately 4′ of the coastlines, and Area B, beyond this boundary, as illustrated in Fig. 3a. Separate training and prediction are performed for these two regions. 20% of the shipborne gravity points in Areas A and B are randomly selected as checkpoints, while the remaining points are assigned as control points, as shown in Fig. 3b. Control points are exclusively used for training the MLP model, and checkpoints are solely used to assess the accuracy of the developed gravity anomaly model. The Details of the shipborne gravity points in Areas A and B are provided in Table 2.

Area division (a) and Shipborne data distribution (b). (a) The blue region indicates areas beyond 4′ from the coastline, and the red region represents areas within 4′. (GMT v6.4.0, https://gmt-china.org/)

Process

After determining the data organization format and partitioning rules, the gravity anomaly model refinement is carried out following these steps. First, standardization is used to remove the differences between different types of input data. This procedure normalizes the raw data, ensuring it has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The formula for standardization is given as follows:

where z represents the standardized value, \(\mu\) is the mean of the input data, σ is the standard deviation, and \({x_i}\) represents the original data.

Next, the selection of MLP neural network parameters should be conducted. The choice of parameters significantly impacts the network’s performance and the training process. The parameters are initially set randomly and continuously adjusted based on training accuracy to achieve the optimal configuration. When training accuracy is low, strategies such as increasing the number of nodes in hidden layers, adding more hidden layers, adjusting batch size, and modifying the learning rate are employed to enhance performance. Hyperparameters are determined through evaluation using both training and validation datasets. In this study, five hidden layers are utilized, with 512, 1024, 2048, 1024 and 512 neurons in each layer, respectively. A batch size of 64 is employed. The Tanh activation function was selected due to its ability to handle both positive and negative values, with an output range of -1 to 1, facilitating more balanced gradients and accelerating the training process. The Adam algorithm was used, which is a gradient-based adaptive optimization method that effectively accelerates convergence and stabilizes the training process. L2 regularization with alpha = 0.01 was applied to avoid overfitting. A learning rate of 0.0001 is adopted.

The structured input and output data are then used to train the MLP. The Adam optimization algorithm iteratively updates weights and biases, allowing the neural network’s output to gradually converge to the training data. The iterations stop when the loss function no longer decreases or when the maximum number of iterations is reached, signaling the completion of the MLP model training.

Finally, the input data of the prediction points is input into the trained MLP model, and the resulting predictions results are restored using the SDUST2022GRA model. The calculation formula is as follows:

where \(\Delta {g_p}\) represents the gravity anomaly value obtained at the predicted point of interest, \(\Delta {(\Delta g)_{output}}\) represents the predicted output gravity anomaly difference, and \(\Delta {g_{SDUST2022GRA}}\) represents the gravity anomaly value from the SDUST2022GRA model at the predicted interest point.

Based on the gravity anomaly values of each predicted point of interest, the 1’×1’ grid resolution gravity anomaly model (referred to as the MLP_GRA model) is constructed for the Gulf of Mexico region. Figure 4 presents the specific workflow for building the gravity anomaly model, comprising data preprocessing, the training phase, and the prediction phase.

Results

This section presents the development of the gravity anomaly model and evaluates its precision. Initially, the procedure for training the MLP model using structured data to establish the gravity anomaly model is outlined. Then, using shipborne gravity measurements as a benchmark, the proposed model’s performance is assessed against existing gravity models. The assessment includes global statistical analysis and depth-stratified evaluations to thoroughly verify the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Establishment of gravity anomaly model

First, the MLP neural network is trained separately using the input and output data from Regions A and B. The input data consists of the differences in longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly, geoid height, bathymetry and sediment thickness between the control points and the surrounding 8’×8’ grid points in both subregions. The output data is the differences between the shipborne gravity anomalies at the control points in the two subregions and the corresponding values from the SDUST2022GRA model. During training, the relationship between input and output data is established. The Adam optimization algorithm continuously updates the weights, with the output gradually converging to the output data. Through continuous iteration, MLP models for the two subregions are established, and the training accuracy for both regions is shown in Table 3.

Finally, the differences in longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly, geoid height, bathymetry and sediment thickness between the prediction points and the surrounding 8’×8’ grid points in both subregions are input into the MLP model. The output is then restored using the SDUST2022GRA model, resulting in the predicted gravity anomaly values at the prediction points. The MLP_GRA model for the Gulf of Mexico region is established using the predicted gravity anomaly values from the two subregions. Figure 5 illustrates the MLP_GRA model generated by the MLP neural network, the SDUST2022GRA model used as input, and the resulting differences between the two models. The differences are mainly concentrated around 0 mGal, with larger deviations observed near coastlines and regions with significant topographic variation. This demonstrates that the method effectively improves satellite-derived gravity anomalies, especially in coastal regions and areas with pronounced topographic variations where accuracy is lower.

Gravity anomaly model and the differences between MLP_GRA and SDUST_2022GRA models. (a) MLP_GRA model. (b) SDUST2022GRA model. (c) MLP_GRA - SDUST2022GRA. (GMT v6.4.0, https://gmt-china.org/)

Accuracy evaluation

The accuracy of the MLP_GRA model is assessed by comparing it with the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models. To facilitate this comparison, cubic spline interpolation is applied to interpolate the MLP_GRA, SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1, and DTU21GRA models to the checkpoints. Table 4 presents the statistical results of this comparison.

Table 4 shows that the MLP_GRA model reduces the STD by 0.40 mGal, 0.54 mGal and 0.39 mGal, compared to the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models, respectively. Additionally, the MAE of the MLP_GRA model is reduced by 0.32 mGal, 0.37 mGal and 0.27 mGal, compared to the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models, respectively. These results indicate that the MLP_GRA model is closer to the shipborne gravity anomalies compared to the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models.

The differences between the MLP_GRA, SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models and the shipborne gravity anomalies at the checkpoints are presented as distribution histograms in Fig. 6. The error distributions of all four models approximate a normal distribution. The statistical results show that the percentages of the differences within the ± 6 mGal range are 96.09%, 94.17%, 93.52%, and 94.29%, respectively. The gravity anomaly difference of the MLP_GRA model greater than ± 9 mGal accounts for 1.29%, which is lower than the proportions for the SDUST2022GRA model (1.88%), SIO_V32.1 model (2.18%) and DTU21GRA model (1.93%). Consequently, the differences between the MLP_GRA model and the shipborne gravity anomalies are more concentrated, indicating that the MLP_GRA model more accurately reflects the gravity anomaly information.

To analyze the accuracy of the MLP_GRA model across different depths, the differences among the four models at various depths of the checkpoints were calculated. As shown in Table 5, the MLP_GRA model exhibits varying degrees of improvement across different depth ranges compared to the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models. In the 1000 to 2000 m depth range, the standard deviation (STD) decreases by 0.75 mGal, 0.84 mGal and 0.87 mGal, respectively. The MLP_GRA model exhibits the most significant accuracy improvement compared to the SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models within this depth range. This improvement can be attributed to the considerable topographic variations at the checkpoint locations, which result in reduced precision in the gravity anomalies derived from altimetry data. These results demonstrate that the proposed method effectively refines gravity anomalies obtained from altimetry data.

Discussion

The MLP_GRA model integrates multiple sources of data, such as sediment thickness and bathymetry. This section investigates the effect of various data combinations on the accuracy of the established MLP_GRA model. Initially, differences in longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly and geoid height between the control points and the surrounding 8′×8′ grid points serve as the foundational input data. These inputs are then combined with other data sources to train the MLP neural network. Subsequently, these foundational and combined data are input into the corresponding MLP model. The predicted results are restored using the SDUST2022GRA model. Using the predicted gravity anomaly values, a gravity anomaly model for the Gulf of Mexico is developed. The accuracy of the model is evaluated by interpolating its values at designated checkpoints. Table 6 presents the statistical results, where ΔB, ΔL, Δ(Δg), ΔN, Δh and ΔT represent the differences in longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly, geoid height, bathymetry, and sediment thickness, respectively.

Table 6 reveals that models based solely on foundational data, or those combining foundational data with depth differences or sediment thickness differences, exhibit lower accuracy compared to the MLP_GRA model. Among these, the model established by combining bathymetry difference, sediment thickness difference and foundational data achieves the highest accuracy, while the model based solely on the foundational data shows the lowest accuracy. This confirms that marine gravity anomalies are influenced by seafloor topography undulations and crustal density variations. Furthermore, models constructed using two data combinations demonstrate higher accuracy than those based on a single data, with the model based on three data combinations yields the best results.

It can be observed that combining sediment thickness data with foundational data improves the STD and MAE by 0.05 mGal and 0.06 mGal, and by 0.02 mGal and 0.04 mGal, respectively, compared to using only foundational data or the combination of foundational data with bathymetry. The incorporation of sediment thickness data results in the greatest improvement in model accuracy, which can be attributed to the relatively high sediment thickness in the Gulf of Mexico region.

Conclusion

This study refines the satellite-derived gravity anomaly model by employing MLP neural networks to integrate the differences in multi-source geophysical data between control or prediction points and grid points, based on shipborne gravity data. The multi-source geophysical data include longitude, latitude, gravity anomaly, geoid height, bathymetry and sediment thickness. Using this approach, the gravity anomaly model, MLP_GRA, with a 1′×1′ grid resolution, was developed for the Gulf of Mexico (261–278 °W, 15–32 °N).

Compare the MLP_GRA, SDUST2022GRA, SIO_V32.1 and DTU21GRA models with shipborne gravity anomalies at the checkpoints. The results show that the MLP_GRA model exhibits higher consistency with the shipborne gravity data. A comparison of shipborne gravity anomalies at the checkpoints across different depth ranges shows that the MLP_GRA model achieves varying degrees of improvement over the other three models in all depth ranges. These results confirm that integrating differential multi-source geophysical data with the MLP neural network, based on shipborne gravity data, can effectively refine the gravity anomaly model derived from satellite altimetry. Although the MLP method demonstrates stronger nonlinear fitting capabilities in gravity anomaly refinement modeling, it still has limitations including strong data dependence and lack of physical interpretability.

Data availability

All the data necessary to assess the conclusions of the paper are provided within the manuscript. For further data related to this study, please contact Chengjun Xiao (chengjunxiao904@163.com).

References

King-Hele, D. The shape of the earth. Science 192, 1293–1300 (1976).

Annan, R. F. & Wan, X. Mapping seafloor topography of Gulf of Guinea using an adaptive meshed gravity-geologic method. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 301 (2020).

Zhang, M. H., Qiao, J. H., Zhao, G. X. & Lan, X. Y. Regional gravity survey and application in oil and gas exploration in China. China Geol. 2, 382–390 (2019).

Bobojć, A. Application of gravity gradients in the process of GOCE orbit determination. Acta Geophys. 64, 521–540 (2016).

Hwang, C. & Hsu, H. Y. Shallow-water gravity anomalies from satellite altimetry: case studies in the East China sea and Taiwan Strait. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 31, 841–851 (2008).

Wan, X., Annan, R. F. & Wang, W. Assessment of HY-2A GM data by deriving the gravity field and bathymetry over the Gulf of Guinea. Earth Planet Space. 72, 151 (2020).

Gopalapillai, G. S. & Mourad, A. G. Detailed gravity anomalies from geos 3 satellite altimetry data. J. Geophys. Res-Sol Ea. 84, 6213–6218 (1979).

Moritz, H. Least-squares collocation. Rev. Geophys. 16, 421–430 (1978).

Sandwell, D. & Smith, W. Marine gravity anomalies from GEOSAT and ERS-1 satellite altimetry. J. Phys. Res. 102, 10039–10054 (1997).

Hwang, C., Guo, J., Deng, X., Hsu, H. Y. & Liu, Y. Coastal gravity anomalies from Retracked Geosat/GM altimetry: improvement, limitation and the role of airborne gravity data. J. Geodesy. 80, 204–216 (2006).

Andersen, O. B., Knudsen, P. & Berry, P. A. M. The DNSC08GRA global marine gravity field from double Retracked satellite altimetry. J. Geod. 84, 191–199 (2010).

Sandwell, D., Müller, D., Smith, W., Garcia, E. & Francis, R. New global marine gravity from CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 reveals buried tectonic structure. Science 346, 65–67 (2014).

Zhu, C. et al. Marine gravity determined from multi-satellite GM/ERM altimeter data over the South China Sea: SCSGA V1.0. J. Geod. 94, 50 (2020).

Fang, Y. et al. A fast method for calculation of marine gravity anomaly. Appl. Sci. 11, 1265 (2021).

Guo, J. et al. SDUST2023GRA_MSS: the new global marine gravity anomaly model determined from mean sea surface model. Sci. Data. 12, 108 (2025).

Sandwell, D. et al. Toward 1-mGal accuracy in global marine gravity from CryoSat-2, envisat, and Jason-1. Lead. Edge. 32, 892–899 (2013).

Kim, J. W., von Frese, R. R. B., Lee, B. Y., Roman, D. R. & Doh, S. J. Altimetry-Derived gravity predictions of bathymetry by the gravity-geologic method. Pure Appl. Geophys. 168, 815–826 (2011).

Fan, D., Li, S., Li, X., Yang, J. & Wan, X. Seafloor topography Estimation from gravity anomaly and vertical gravity gradient using nonlinear iterative least square method. Remote Sens. 13, 19 (2020).

Guo, J. et al. Accuracy comparison of marine gravity derived from HY-2A/GM and CryoSat-2 altimetry data: a case study in the Gulf of Mexico. Geophys. J. Int. 230, 1267–1279 (2022).

Zhu, C. et al. Recovering gravity from satellite altimetry data using deep learning network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 5911311 (2023).

Zhou, S. et al. Predicting bathymetry using multisource differential marine geodetic data with multilayer perceptron neural network. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 17, 2393255 (2024).

Shiblee, M., Kalra, P. K. & Chandra, B. Time series prediction with multilayer perceptron (MLP): a new generalized error based approach. In Advances in Neuro-Information Processing. (eds Mario Köppen, Nikola Kasabov, & George Coghill) 37–44 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg) (2009).

Zhu, C. et al. Refining Altimeter-Derived gravity anomaly model from shipborne gravity by Multi-Layer perceptron neural network: a case in the South China sea. Remote Sens. 13, 607 (2021).

Nguyen, L., Levander, A., Niu, F., Morgan, J. & Li, G. Insights on formation of the Gulf of Mexico by rayleigh surface wave imaging. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 23, eGC010566 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. The SDUST2022GRA global marine gravity anomalies recovered from radar and laser altimeter data: contribution of ICESat-2 laser altimetry. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 16, 4119–4135 (2024).

Sandwell, D., Harper, H., Tozer, B. & Smith, W. Gravity field recovery from geodetic altimeter missions. Adv. Space Res. 68, 1059–1072 (2019).

Andersen, O. B., Rose, S. K., Abulaitijiang, A., Zhang, S. & Fleury, S. The DTU21 global mean sea surface and first evaluation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 15, 4065–4075 (2023).

Zingerle, P., Pail, R., Gruber, T. & Oikonomidou, X. The combined global gravity field model XGM2019e. J. Geod. 94, 66 (2020).

Straume, E. et al. GlobSed: updated total sediment thickness in the world’s oceans. Geochem. Geophy Geosy. 20, 1756–1772 (2019).

Knudsen, P., Andersen, O., Maximenko, N. & Hafner, J. The mean dynamic topography model DTUUH22MDT from satellite and in-situ observations. in 2023 Ocean Surface Topography Science Team Meeting. 67.

Schaeffer, P. et al. The CNES CLS 2022 mean sea surface: short wavelength improvements from CryoSat-2 and SARAL/AltiKa High-Sampled altimeter data. Remote Sens. 15, 2910 (2023).

Hwang, C. & Parsons, B. Gravity anomalies derived from Seasat, Geosat, ERS-1 and TOPEX/POSEIDON altimetry and ship gravity: a case study over the Reykjanes ridge. Geophys. J. Int. 122, 551–568 (1995).

Smith, W. On the accuracy of digital bathymetric data. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 9591–9603 (1993).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2, 359–366 (1989).

Zhou, S. et al. Bathymetry of the Gulf of Mexico predicted with multilayer perceptron from multisource marine geodetic data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 4208911 (2023).

Jin, X., Guo, J., Shen, Y., Liu, X. & Zhao, C. Application of singular spectrum analysis and multilayer perceptron in the mid-long-term Polar motion prediction. Adv. Space Res. 68, 3562–3573 (2021).

Gardner, M. W. & Dorling, S. R. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—a review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 32, 2627–2636 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank NOAA for providing the shipborne gravity data and sediment thickness data, ICGEM and Shandong University of Science and Technology for the gravity anomaly models, SIO for the bathymetric and gravity anomaly models, DTU for the mean dynamic topography and gravity anomaly models, and CNES and CLS for the mean sea level model.

Funding

This study is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 42430101, 42274006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.X. conducted the experiments, performed data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. J. G. assisted in the development of the research design, supervised, and facilitated the data analysis. S. L., X. L., C. Z., and H. L. contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, C., Guo, J., Zhu, C. et al. Refining satellite Altimetry-Derived gravity anomaly model with shipborne gravity using multilayer perceptron neural networks. Sci Rep 15, 19467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04619-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04619-8