Abstract

This paper proposes a bearing fault diagnosis method based on Kolmogorov–Arnold Convolutional Network: Adaptive Context-aware Graph Channel Attention with Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (KANConv-ACGCA-SENet). Firstly, a new structure of KANs is applied to Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for replacing traditional linear convolutional kernels. Secondly, a dual-branch fusion attention module, comprising the ACGCA modules, is proposed for use in learning fault features. This is achieved by capturing feature differences and utilising non-local(NL) operations, thereby enhancing the feature representation ability under different working conditions. Subsequently, context-aware features and non-local aggregation features are combined with the objective of obtaining global features. Finally, the SENet module is introduced with the aim of further enhancing the key information in the global features and improving the robustness of the model. The experimental results demonstrate that the method proposed in this paper achieves an average accuracy of 99.63% in a single load scenario and 99.05% in a variable working condition scenario. It exhibits high diagnostic accuracy and a superior capacity for generalization, proves that the KANConv represents a formidable alternative to the existing CNN-based variants for bearing fault diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of bearing fault diagnosis, deep learning models have demonstrated exceptional ability to process intricate signal data. By learning deeply about patterns and anomalies in signals, these models are able to accurately identify the characteristics of faults. Whether analyzing vibration signals or acoustic signals, they can effectively detect early wear, damage, or other fault types in bearings. This enables the timely warning and maintenance of bearing failures, which is of significant importance in industrial settings. Against the backdrop of the accelerated advancement and extensive deployment of deep learning modeling, the role of deep learning-based bearing fault diagnosis is becoming increasingly critical in predictive maintenance and the enhancement of mechanical system reliability.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)1 are capable of extracting local features from input data in a layer-by-layer manner and subsequently refining higher-level features, which renders them particularly effective in the identification and diagnosis of faults. Currently, CNNs are extensively utilized in this domain and have undergone a continuous process of evolution, resulting in the emergence of numerous classical models. However, conventional network models still face problems, including inadequate diagnostic precision and an inflexible structure. To improve the precision of conventional single-sensor fault diagnosis, He et al.2 proposed an intelligent diagnostic approach based on dual-scale residual networks, which enhances the feature fusion capacity by learning both deep and shallow features at two scales and capturing fault-related information in disparate spatial dimensions. Ruan et al.3 optimized the parameter specifications of the CNN to enhance efficiency. Specifically, the input size of the CNN is determined based on the fault cycles of various fault types and the rotation frequency of the axes. Subsequently, an exponential function is used to fit the envelope of the decay acceleration signals associated with each fault cycle, and the kernel size of the CNN is defined according to the length of the signals at different decay ratios. Jia et al.4 proposed a reinforced CNN, the Gramian Time Frequency Enhancement CNN (GTFE-Net), to improve the ability of feature extraction against noise interference. The network consists of three parallel branches that process the original signal, the Gramian Noise Reduction (GNR) denoised signal, and the spectrum. The GNR is embedded within the GTFE-Net to enable the network to prioritize feature extraction over noise suppression. Udmale et al.5 proposed the Memetic Algorithm (MA) to optimize both parameters and architecture of Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), constructing a more compact and efficient framework.

The aforementioned research progress is primarily concerned with the optimization of the networks’ structure or parameters. While these works predominantly focused on structural optimization, such single-dimensional approaches lack the integration of functionally-oriented modules for targeted functionality enhancement. For this reason, Lu et al.6 introduced the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA)7 module into the network model, which adaptively captures the interchannel dependencies through a simple and efficient one-dimensional convolution without the need for dimensionality reduction or dimensionality enhancement process, thus enhancing the feature representation capability of deep convolutional neural networks. Yu et al. designed a Dynamic Graph Embedding (DGE)8 module with an edge dropout mechanism to improve the adaptive capability of the model, which dynamically transforms the implied fault features extracted from the original bearing vibration signals into higher-level graph structure features. Xue et al.9 improved the feature recognition capability of the diagnostic network by incorporating a channel attention mechanism as a fusion strategy for their model. This approach uses the attention mechanism to identify and integrate key features from a large amount of sensor data, which significantly improves the fusion performance.

The aforementioned studies have concentrated on the design of modules and the introduction of attention mechanisms. While these approaches have made notable advancements, their persistent reliance on linear convolutional kernel operations not only causes fundamentally restricts in the depth of model feature extraction, but also constrains both the feature comprehension and the capabilities in distinguishing analogous fault characteristics. Furthermore, the introduction of a single attention mechanism may result in an excessive focus on specific features, while simultaneously disregarding equally crucial information. In practical industrial applications, bearings are required to operate under a variety of conditions10. Variable working conditions characterized by fluctuating operational parameters (e.g., load, speed), challenge intelligent diagnosis through domain shifts and scarce fault samples.11 While a given model may perform well under a single operating condition, the diagnostic results may not be satisfactory when migrating to variable or complex conditions.

Additionally, other approaches enhance diagnostic performance by targeted strategies: end-to-end sequence learning (with kurtogram inputs) resolves feature selection12, multi-sensor fusion optimization (via Distinctive Frequency Components with adaptive weighting) mitigates fusion bias13, and meta-learning (enabling dynamic feature space adaptation) tackles feature redundancy14, collectively offering valuable insights for researchers in advancing fault diagnosis.

In light of the aforementioned arguments, we formulate a methodology which employs model structure optimization combined with module design and integration.

Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs)15 is a novel network structure proposed in April 2024 by Liu et al. at MIT. The characterization of bearing faults typically involves the analysis of intricate vibration patterns and signal variations. KANs are capable of automatically learning and extracting these complex fault characteristics through the accurate capture of patterns and relationships in the data, without the reliance on predefined fixed functions15. In comparison to traditional Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs), KANs demonstrate superior performance in handling complex nonlinear problems. Moreover, the design of KANs makes the model still effective with fewer parameters, and the learnable functions that can be visualized make the model well interpretable. These characteristics make KANs especially adept at identifying abnormal bearing behavior, which offers a novel approach to bearing fault diagnosis.

This paper proposes a bearing fault diagnosis method based on Kolmogorov–Arnold Convolutional Network: Adaptive Context-aware Graph Channel Attention with Squeeze-and-Excitation Network (KANConv-ACGCA-SENet). The method is designed to optimize the diagnostic model’s structure, reinforce feature representation, accurately identify feature differences, and improve generalization under variable operating conditions. As a result, the model’s overall capability is advanced. The principal conclusions drawn from the analysis of the experimental results are as follows:

-

The introduction of KANs to the CNN-based bearing fault diagnosis model accomplishes the structural innovation. KANConv replaces the linear convolution kernels in traditional CNNs with nonlinear B-spline, introducing adaptive nonlinearity at the convolutional operation level. As illustrated by the t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) feature visualization, the methodology presented in this paper exhibits excellent performance in learning data features and fault diagnosis.This proves that the KANConv represents a formidable alternative to the existing CNN-based variants for bearing fault diagnosis.

-

This paper proposes a dual-branch fusion attention mechanism called ACGCA, which captures feature differences and acquires aggregation features through context-awareness and non-local operations, thereby achieving comprehensive extraction of feature representations. As illustrated by the t-SNE feature visualization, the module exhibits a high degree of feature extraction, which can markedly improve the model’s diagnostic accuracy. The ablation study indicated that adding ACGCA alone could increase the accuracy by 6.07%.

-

The comprehensive bearing fault diagnosis experiments demonstrate that, in comparison with Multitask Learning with Continuous Wavelet Transform and Long Short-Term Memory Model (MTL-CWT-LSTM)16, Markov Transition Field and Residual Neural Network (MTF-Resnet)17, Variational Mode Decomposition Combined with CNN (VMD-CNN), CNN-LSTM18, Temporal Convolutional Network-KAN (TCN-KAN), and improved 2DCNN19, this paper’s method exhibits a superior diagnostic performance and a more robust generalization performance. The single-load accuracy reaches 99.63%, while the accuracy for variable operating conditions reaches 99.05%.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical foundations of the model. Section 3 details the innovation module and model structure. Section 4 comprises the experimental validation and analysis. Section 5 provides a summary of the full paper.

Relevant theoretical and model-based foundations

Introduction of Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks

The Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs)20 has become a principal component of deep learning applications due to its excellent ability to approximate nonlinear functions21,22. However, the complex and nested structure of MLPs leads to a rapid increase in the number of parameters with the increase in the number of network layers and the number of neurons per layer. This approach is prone to overfitting, gradient vanishing, or gradient explosion problems, and it offers limited interpretability.

To address this problem, researchers have proposed KANs as a more accurate and interpretable alternative to MLPs. The theoretical foundation of KANs is the Kolmogorov–Arnold theorem, which states that a multivariate continuous function “f” within a closed interval can be decomposed into a finite combination of univariate continuous functions23,24,25, as shown in (1). This form of decomposition enables KANs to approximate complex multivariate functions by combining univariate functions, thereby enabling the effective learning of complex patterns in high-dimensional data.

where \(\Phi _{q}\) are continuous functions, \(\varphi _{q,p}\) are univariate functions that map each input variable \(x_{p}\). At the same time, \(\varphi _{\textrm{q,p}}\) are parameterized functions with learnable parameters.

Unlike conventional MLPs, KANs employ learnable activation functions at the edges of the network instead of applying a fixed activation function to each neuron. Therefore, in KANs, single-variable functions replace the weight matrices typically employed in traditional MLPs, significantly reducing the number of model parameters. These learnable univariate functions are parameterized using B-spline basis functions, enabling them to dynamically adapt their forms based on input features. This design enhances the network’s representational power, allowing it to capture complex relationships in data more effectively. Equation (1) represents a combination of two layers of KANs: the internal functions constitute a KANs layer with \(\mathrm {n_{in}=n}\) and \(\mathrm {n_{out}=2n+1}\), whereas the external functions constitute a KANs layer with \(\mathrm {n_{in}=2n+1}\) and \(\textrm{n}_{\textrm{out}}=1\)26, which can be shown in (2).

where p denote the input dimension, and q denote the output dimension. The matrix representation of the KANs layer is shown in (3).

The combination of multiple KANs layers permits for the construction of deep KANs networks. The sufficient depth of the network (i.e., the sufficient number of layers) enables it to capture more complex patterns and dependencies in the data, which can enhance its ability to model more complex functions. Each KANs layer transforms the input x through a series of learnable functions, thereby endowing the network with a high degree of adaptability and functionality26. The structure of the deep KANs network can be represented by (4), and the corresponding network schematic is illustrated in Fig. 1.

where each \(\Phi _{\textrm{L}}\) represents a KANs layer.

The distinctive structure, high adaptability and the application of B-spline based learnable activation functions in KANs can significantly improve the accuracy, computational efficiency and interpretability of the model. Concurrently, the localization property of the B-spline function enables KANs to retain local features throughout the training process, thereby reducing the phenomenon of catastrophic forgetting. Inspired by KANs, some researchers have applied them to vision tasks27 and remote sensing classification28, confirming its efficacy in these domains. In the domain of time series analysis and prediction, the research carried out by Vaca-Rubio et al.29 and Genet et al.30 have also demonstrated the specific advantages of KANs in enhancing the performance of forecasting models. Similarly, KANs have been employed by researchers for power system modeling31 and other applications, which indicates the extensive potential for its utilization. Consequently, the bearing fault diagnosis model based on KANs is also expected to be a powerful alternative to the existing bearing fault diagnosis and preventive maintenance models.

Kolmogorov–Arnold convolutional network (KANConv)

While KANs is an excellent tool in terms of accuracy, interpretability, and applicability, it is not without limitations32.

-

Although KANs are more parametrically efficient than MLPs, they require longer training periods.

-

While the learnable spline functions have the potential to improve the expressive capacity of KANs, they also introduces additional complexities into the design and training process, leading to increased training costs.

-

While KANs have been demonstrated to perform well on small-scale datasets, further research and validation are necessary to ascertain their capacity to generalize to large-scale datasets15.

In comparison, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are capable of accelerating the training process by reducing the dimensionality of feature maps through the utilisation of pooling layers, parallel computing on large-scale data, and other measures. This allows them to process data in a more effective manner. The deep structure of CNNs is able to automatically extract multilevel features and displays strong feature extraction ability, particularly when dealing with large-scale datasets. However, it has been observed that CNNs may sometimes fail to fully leverage the crucial information in the data when processing sparse data or high-dimensional features. Furthermore, the opaque nature of CNNs renders them weakly interpretable. Interpretable analysis methods typically necessitate considerable manual experiences and judgment33, which can be problematic when transparent decision-making is required.

In this paper, we introduce KANConv, a novel integration of KANs and CNNs designed to achieve a balance between performance and efficiency. KANConv represents an innovative extension of convolutional neural networks by combining the strengths of both frameworks34. At its core, it replaces the fixed convolutional kernel weights in traditional CNNs with learnable nonlinear activation functions. This transformation renders the convolution operation nonlinear, enabling it to dynamically adapt to input data, as demonstrated in Eq. (5).

where K represents the size of the convolutional kernel, \(\textrm{Spline}(\textrm{W}_\textrm{k})\) denotes the learnable function parameterized by B-splines, \(W_{\textrm{k}}\) refers to the weight in the convolution operation, corresponding to the weight value \(\mathrm {W_{ij}}\) at a single position within the convolutional kernel matrix.

where \(\mathrm {f_{ij}(x)}\) represents the learnable function corresponding to the weight position, \(\mathrm {B_k(x)}\) denotes the spline basis function, and \(\mathrm {c_{ij}^k}\) is its coefficient.

The kernel of the KANConv differs from that of a conventional CNNs. It can be regarded as a linear layer of KANs, comprising four input and one output neurons. For each convolutional kernel of size \(K\times K\), each element in the matrix is corresponding to a learnable activation function defined by a spline basis function. The number of element parameters is gridsize + 2. As a result, each KANConv layer contains \(K^{\wedge }2\) (gridsize + 2) parameters. The definitions of the aforementioned element are given in (7).

For image processing tasks, each element of a convolution kernel is summed after applying an activation function, generating an element of the feature map. Specifically, each output pixel derived through the convolution operation represents a weighted sum of input pixels transformed by the activation function. The utilisation of the spline function confers a distinct advantage in terms of the more efficient capture of non-linear relationships35, as well as a potential reduction in the number of parameters through a diminution of the number of non-convolutional layers34. Such a design not only promotes the overall flexibility and adaptability of the model, but it also optimizes the parameter efficiency and expressive power of the CNNs.The matrix representation of the KANConv is shown in (8).

KANConv-ACGCA-SENet fault diagnosis modeling

Adaptive context-aware graph channel attention

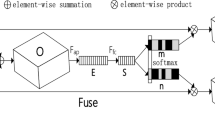

To extract bearing fault features in a comprehensive manner, accurately discern the distinctions between the features at a specific location and those in the surrounding area, assist the model in identifying the features and modes of bearing faults under diverse operational conditions with greater precision, and diminish the computational redundancy and enhance the generalization ability36, this paper proposes Adaptive Context-aware Graph Channel Attention (ACGCA), whose structural diagram is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The ACGCA module employs a parallel approach, whereby the input features are distributed into two branches.

Branch one is the process of context-aware. The input feature map, hereafter referred to as the original features, is partitioned into blocks of varying sizes (1 x 1, 2 x 2, 3 x 3, 6 x 6), with each block undergoing Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPP)37 processing. A 1 x 1 convolution operation is performed on each pooled scale feature to circumvent the limitations of SPP. This allows for the contextual features across channels to be combined in order to generate multiscale perceptual features. Subsequently, the multiscale perceptual features are upsampled to the same dimensions as the original feature map through the utilisation of bilinear interpolation38, which process can be represented by (9).

where \(\textrm{f}_\textrm{v}\) are original features, \(\mathrm {P_{ave}(f_{v},j)}\) denotes the average division of the original features into \(\mathrm {k(j)}\times \mathrm {k(j)}\) blocks,

\(\mathrm {k(j)\in \{1,2,3,6\}}\), \(\mathrm {F_j}\) denotes the convolution operations, \(\textrm{U}_{\textrm{bi}}\) denotes bilinear interpolation.

Subtracting the original features from the upsampled multiscale perceptual features allows us to obtain the contrast features. The inherent discrepancies of these contrast features assist in the discernment of the distinctions between specific locations and their surrounding areas. Subsequently, contrast features are employed to instruct the auxiliary network in learning the relative significance of the fault features across varying scales, thereby enabling the calculation of a weight map for each scale. Finally, this weighted map is multiplied by the multiscale perceptual features and summed, after which it is divided by the sum of all weights to obtain the weighted multiscale perceptual features. The final context-aware features are obtained by combining the weighted multiscale perceptual features with the raw features, as shown in (10).

where \(\textrm{f}_\textrm{v}\) are original features, \(\omega _{j}\) are weight maps, \(s_{j}\) are multiscale perceptual features.

This context-aware attention mechanism captures the inherent characteristics of bearing fault features through feature comparison, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to generalize to new, previously unseen datasets.

Branch two is the process of input features undergoing processing within the adaptive graph channel attention mechanism. The input feature graph is initially compressed into a \({\mathbb {C}}\times 1\times 1\) shape through the application of adaptive average pooling. Subsequently, the pooled features are subjected to a feature mapping layer corresponding to the linear embedding function Fr , which is capable of capturing abundant characteristic information. After this, the resulting features are flattened and transposed to obtain an initial weight of attention. The aforementioned linear embedding function can be expressed by (11).

where \(\textrm{W}_{\textrm{m}}\) is a weight matrix to be learned, \(\textrm{x}_{\textrm{in}}\) denotes the input feature map.

Thereafter, the Adaptive Graph Convolutional Module (AGCM)39 is employed to execute Non-Local (NL) operations. The initial attention weights are first normalized through the application of a softmax function, after which they are expanded to a size that can be multiplied by the initialized adjacency matrix A0, designated as A1. This is followed by a multiplication of A1 and A0, and finally, the learnable adjacency matrix A2 is added, thus obtaining the final adjacency matrix A.

The nonlocal aggregation of features is achieved through matrix multiplication of the adjacency matrix A with the previously flattened and transposed features. In this process, the number of columns of the feature vector is equivalent to the number of columns of A, which yields the weighted features. Subsequently, the weighted features are processed by the ReLU activation function and the linear embedding function F’r. Follow this, the weighted features undergo a reshaping operation and are then processed by a 1x1 convolution and a Sigmoid activation function to generate the final attention weights. Ultimately, the initial input features of Branch two are multiplied by the final attention weights, resulting in feature recalibration and the attainment of the final non-local aggregation features.

The procedure described in Branch two can be represented by the following equation.

where \(F_{r}\), \(F_{r}^{\prime }\) are linear embedding functions, which forms the bottleneck structure. \(F_r(AAP(x))\) is the input of AGCM, A denotes the adjacency matrix in AGCM.

As each feature vertex in a graph convolutional network is mutually exclusive40, we utilizes the bottleneck structure41 to reduce feature redundancy. This entails reducing the parameters of the convolutional layer preceding the adaptive graph convolution module to \(C\times (C/{\textbf{r}})\) and reducing the adjacency matrix within the adaptive graph convolution module to \((C/{\textbf{r}})\times (C/{\textbf{r}})\).

The adaptive graph channel attention is distinguished by the richness of the extracted features, as well as the adaptive property that enables the network to discern the interconnections between different features and to adapt to disparate types of bearing data and fault, including subtle variations that emerge under varying operational conditions.

The results of the two branches are ultimately combined to generate the global features, which serve as the output of ACGCA.

Further features extraction based on the squeeze-excitation mechanism

In order to enhance the robustness of KANConv-ACGCA and further the extraction of critical fault features in bearings, this paper introduces Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SENet). By explicitly modelling the interdependencies between the convolutional feature channels42, it is possible to significantly enhance the diagnostic performance with only a slight impact on computational efficiency.

The SENet’s Squeeze-Excitation block is designed to construct a corresponding SE block for the purpose of performing feature recalibration for any given transformation43, as shown in (13).

where \(\mathrm {X\in R^{H^{\prime }\times W^{\prime }\times C^{\prime }}}\), \(U\in R^{\mathrm {H\times W\times C}}\) . In the SE block, the feature mapping \({\textbf{U}}=[{\textbf{u}}_1,{\textbf{u}}_2,\ldots ,{\textbf{u}}_c]\) is achieved through a two-step process for feature recalibration, the structure of which is illustrated in Fig. 3.

The “squeeze” step is executed initially. Feature maps are aggregated over the spatial dimension H\(\times\)W by global average pooling to extract the global statistics of each channel to form a channel descriptor. This descriptor captures the global feature distribution of the ACGCA module’s output, which allows the low-level network to utilize the global information. The squeeze operation is realized by (14).

where \(z_{\textrm{c}}\) denotes statistical descriptor of the channel c, \(\mathrm {F_{sq}}\) denotes the squeeze process, H and W denote the height and width of feature map \({\textbf{u}}_c\), \(\mathrm {u_c(i,j)}\) represents the value of the feature map at location \((\textrm{i,j})\) in channel c.

Subsequently, the “excitation” step is executed, wherein the network deploys a self-gating mechanism to calculate weights for each channel based on the interrelationships between the channels, which reflect their importance to the sample. These weights are calculated by connecting the two fully connected layers in series with the ReLU activation function and outputting them via a sigmoid function. The procedure in question not only ensures the flexibility of the weights, but also allows multiple channels to receive higher weights simultaneously, thereby guaranteeing that the weights are non-mutually exclusive. The excitation operation is realized by (15).

where \(\textrm{F}_\textrm{ex}\) denotes the excitation process, \(\mathrm {W_I\in R^{\frac{c}{r}\times C}}\), \(\textrm{W}_{\textrm{II}}\in R^{\mathrm {C\times \frac{c}{r}}}\), z is the global channel descriptor obtained by squeeze.

Finally, the feature mapping U is reweighed in accordance with the calculated weights, yielding the final SE block output as expressed in (16).

where \(\tilde{{\textbf{X}}}=[\tilde{\textrm{x}}_1,\tilde{\textrm{x}}_2,\ldots ,\tilde{\textrm{x}}_c]\) , \(\textrm{F}_{scale}(\textrm{u}_{\textrm{c}},\textrm{s}_{\textrm{c}})\) denotes the channel-wise multiplication between the feature map \(\mathrm {u_c\in R^{H\times W}}\) and the scalar \(\textrm{s}_{\textrm{c}}\)42.

The utilisation of the squeeze-excitation mechanism preserves the comprehensive global information present in the ACGCA module’s output. This not only facilitates the deliberate enhancement of valuable features through the comprehension of the overall information, but also simultaneously attenuates the influence of relatively inconsequential features, such targeted output has a direct, positive impact on the diagnostic accuracy of bearing faults.

Structure of KANConv-ACGCA-SENet model

In this paper, we propose a rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on KANConv and ACGCA-SENet (KAS), the model structure of which is illustrated in Fig. 4. The initial step is the input of the raw data into the KANConv layers. Each of these layers comprises five KANConv modules, each of which performs a 3x3 convolutional operation. The core of each module is a nonlinear learnable activation function, defined by a spline function. Subsequently, a 2x2 maximal pooling layer with a step size of 2 is applied to each KANConv layer. This reduces the computational complexity while increasing the sensory field. Following the application of three sets of KANConv layers and maximum pooling layers, the resulting output feature maps proceed to enter the ACGCA dual-branch fusion attention module, with the objective of attaining a rich global feature representation.

Branch 1 initializes the segmentation of input feature maps into the scales specified in section 3.1, and then performs spatial pyramid pooling on each scale with the aim of capturing contextual information at varying scales. Subsequently, the output of each pooling layer is subjected to further processing through a 1 x 1 convolution layer to learn feature representations at varying scales. The subsequent step involves upsampling the multiscale perceptual features, which have been obtained through a series of pooling and convolution operations at varying scales. This process serves to restore the feature to the size of the original input feature. Subsequently, an auxiliary network is utilized to learn the dissimilarities between the original features and the upsampled features, and a weight map is then calculated to map and weight the upsampled multiscale features. The fused weighted features and the original features are entered into a 1 x 1 convolution layer for dimensionality reduction. Finally, the context-aware features,which have been activated by ReLU, are generated as the output of this branch.

The first step of Branch 2 is the extraction of features through the utilisation of adaptive average pooling and 1 x 1 convolution. The extracted features are then flattened and transposed in order to generate preliminary attention weights, which are subsequently subjected to the second step, the non-local operation. The preliminary attention weights are input into a convolutional layer and then normalized by softmax. This step yields a non-local aggregated feature matrix through a series of matrix transformations, as outlined in section 3.1 and the weighting. The third step is a nonlinear transformation process, during which the feature matrix passes through a layer of convolution and a ReLU activation function. In the fourth step, the reshaped features are subjected to a 1 x 1 convolution and a sigmoid activation function to generate the final attention weights. Ultimately, the input features are multiplied by the final attention weights to achieve cross-channel feature recalibration, and the resulting non-local aggregation features are the output of this branch.

Subsequently, the output of the two branches is combined to generate the global features, which are input to the SE module. The SE module comprises a global average pooling layer, two fully connected layers, and two activation layers. The weights calculated by the SE module are applied to the global features through channel-by-channel multiplication, which serves to enhance important features and suppress the unimportant features, thereby achieving a dynamic adjustment of the feature maps.

Remaining components of the model are a flattening layer and two fully connected layers. Ultimately, a Softmax operation should be performed on the model’s output to obtain the probability distribution, which can then be subjected to analysis to yield the diagnostic result.

The method comprises three specialized components: KANConv adaptively extracts features through learnable B-spline-based nonlinear convolutions; ACGCA integrates global information via dual-branch processing combining multi-scale contrast learning and adaptive feature correlations; and SENet emphasizes critical fault features via channel-wise attention.

Validation and analysis of experiment

The graphical abstract of this paper’s methodology is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Data preprocessing

The experimental data presented in this paper were obtained from the bearing datasets provided by the Bearing Data Center at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU)44. For the bearing fault data, a sampling frequency of 12 kHz at the drive end was selected. The bearing failures include inner ring failure, ball failure, outer ring failure, and no failure. Three damage diameters with fault diameters of 0.007 inches (0.1778 mm), 0.014 inches (0.3556 mm), and 0.021 inches (0.5334 mm) are utilized. The datasets comprises three operating conditions, corresponding to 0, 1, and 2 horsepower motor loads (1 horsepower = 735.49875 watts), respectively. In a group, we implemented a ten-class labeling system for bearing faults: no failure was assigned label 0; inner ring failure with three severity levels was labeled 1, 2, 3; ball failure with three severity levels was labeled 4, 5, 6; and outer ring failure with three severity levels was labeled 7, 8, 9, thereby establishing a comprehensive ten-class bearing fault dataset. The ten-class bearing fault data was categorized into four groups according to motor load conditions: Group A (0 hp), Group B (1 hp), and Group C (2 hp) each containing data from a single load condition, while Group D combines mixed load conditions from all three load conditions (0–2 hp, randomized samples). These groups are presented in Table 1.

To more comprehensively capture fault features and avoid overfitting, we set the time step to 1024, the overlap rate to 0.5, and divided the training, validation, and test sets according to a ratio of 7:2:1, using the 2D time-series feature set as the input for the model.

In order to achieve superior results, the hyperparameters are set as follows: the initial learning rate is 0. 001, the number of samples per input is 32, the optimizer is set to Adam, and the loss function employs the Cross-entropy loss function45.

All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti (6GB VRAM) with CUDA 12.1 acceleration. The average training time per epoch was 30 seconds under a batch size of 32.

Diagnostic performance of model

To monitor model convergence and analyze generalization capability, we present synchronized training/validation loss curves and training/validation accuracy curves in Fig. 6. We handle overfitting by parameter-efficient spline-basis function designed in KANConv, capturing complex patterns with fewer parameters. Concurrently, L1 sparsity and entropy constraints regularization mechanism explicitly suppresses noise-sensitive features and enforces balanced weight distribution, achieving optimal trade-offs between generalization and expressivity. The steadily decreasing training loss coupled with stable improvement in validation accuracy experimentally validated this strategy.

In order to demonstrate the cluster distribution of different classes in the feature space in a more intuitive manner, this paper utilises the t-SNE feature visualization technique to illustrate the classification scenario of the original data, the output of the KANConv, and the final result. The t-SNE feature visualization of the validation set samples is graphed in Fig. 7.

The visualization results of the dimensionality reduction indicate that the original input data features exhibit a high degree of randomness and chaos, with a fragmented distribution of individual feature points. It is evident that there is a dearth of discernible structure and correlation between the features. Following processing via the KANConv, preliminary indications of classification effectiveness have been observed; however, the separation and comprehension of extraction features remain inadequate. Following additional processing by ACGCA dual-branch fusion attention and SENet, the final results demonstrate a notable enhancement. Ten categories are now spatially presented with clarity and distinction, and the boundaries between categories are evident, indicating a substantial improvement in differentiation and a more profound feature extraction.

The intricate vibration signal patterns that accompany bearing failures may comprise a multitude of frequency components and time-varying characteristics. The results of the aforementioned analysis demonstrate that the ACGCA proposed in this paper offers a more comprehensive and in-depth feature representation capability to the model. The combination of the ACGCA module with that of the flexibility and interpretability from the excellent KANs structure enhances the model’s ability to recognize these subtle but critical fault features, thereby enabling it to learn and characterize fault modes in vibration signals of the bearing with greater accuracy and reliability. Consequently, the model is capable of making more precise diagnoses of bearing faults of varying types, degrees, and working conditions.

Comparison experiment of single load diagnostic performance

To verify the efficacy of the KAS, Groups A, B, and C were employed to validate its capacity for fault diagnosis in single load scenarios. In order to minimize the impact of randomness on the evaluation of the model’s accuracy, 10 experiments were conducted respectively, resulting in a total of 30 trials. The average value was then calculated as the experimental outcome for each group. We compares the KAS with MTL-CWT-LSTM, MTF-Resnet, VMD-CNN, CNN-LSTM, TCN-KAN, and the improved 2DCNN for fault diagnosis. These models employ linear convolutional kernels and demonstrate structural and modular divergences compared to the proposed model (where the TCN-KAN only integrates a KAN Linear at the final classification stage). The results of these experiments are presented in Table 2.

Following an analysis of the experimental data, it can be concluded that the method presented in this paper demonstrates superior performance in single-load scenarios, with the highest recognition accuracy and an average accuracy of 99.63%. This represents a 1.47% improvement over the MTL-CWT-LSTM, a 2.23% improvement over the MTF-Resnet, a 4.53% improvement over the VMD-CNN, a 4.23% improvement over the CNN-LSTM, a 7.29% improvement over the TCN-KAN, and a 6.23% improvement over the improved 2DCNN.

As depicted in Fig. 8, the confusion matrix analysis of classification outcomes reveals exceptionally low misclassification rates across all groups. Group A demonstrates an average error rate of merely 0.41% in test set samples, while Group B and Group C maintain even lower average misclassification rates of 0.31% and 0.4% respectively. The collective diagnostic accuracy attains 99.63%, this experimental evidence conclusively substantiates the model’s capability to effectively diagnose bearing faults.

We measured recall, precision, and F1-score on the strictly isolated test set of Group C exclusively to evaluate model capability with independent data. As shown in Table 3, the classification metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) and misclassification sources are reported for all classes from C0 to C9. Among them, three classes (C0, C1, C3) achieve both 100% precision and recall, indicating no misclassification occurred in these categories. The majority of remaining classes maintain exceptionally high F1-scores above 99.5%, demonstrating robust overall performance. Primary errors stem from confusion between specific classes (e.g., C4 misclassified as C5/C8), which may be related to the feature similarity between classes.

Generalization performance of variable operating condition of models

The operational environment of mechanical equipment is often subject to change, which can impact the accuracy of fault diagnosis in rolling bearings. Consequently, the capacity of the fault diagnosis model to accommodate diverse operational scenarios (generalization ability) is of paramount importance. To assess the model’s capacity for generalization, it was trained using Groups A, B, and C, respectively. The mixed Group D, comprising multiple operating conditions, was employed as a test group for diagnosis, thereby evaluating the model’s performance in a variable operating condition scenario. In order to minimize the impact of randomness on the evaluation of the model’s accuracy, 10 experiments were conducted respectively, resulting in a total of 30 trials. The average value was then calculated as the experimental outcome for each group.

Similarly, we compares the KAS with MTL-CWT-LSTM, MTF-Resnet, VMD-CNN, CNN-LSTM, TCN-KAN, and the Improved 2DCNN for fault diagnosis, results of these experiments are presented in Table 4. Where “A-D” indicates that Group A has been selected for model training and Group D has been selected for model testing.

Following an analysis of the experimental data, it can be concluded that the method presented in this paper still demonstrates excellent diagnostic performance with robust generalization under the bearing usage scenario of variable operating conditions, with the highest recognition accuracy and an average accuracy of 99.05%. This represents a 2.66% improvement over the MTL-CWT-LSTM, a 3.92% improvement over the MTF-Resnet, a 4.99% improvement over the VMD-CNN, a 5.8% improvement over the CNN-LSTM, a 10.41% improvement over the TCN-KAN, and a 9.83% improvement over the improved 2DCNN. The results of this comparison are illustrated in Fig. 9.

Ablation study

To validate the effectiveness of individual modules in the proposed model, an ablation study was conducted to evaluate diagnostic performance under different module combinations. All ablation experiments were conducted using models trained on Group B and tested on Group D to ensure consistency in variable operating condition evaluation. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the boxplot displays module configurations along the horizontal axis and diagnostic accuracy on the vertical axis. The central range reflects model stability, while the whiskers indicate data distribution boundaries, with their endpoints representing maximum and minimum values.

Experimental results demonstrate that the baseline model using solely KANConv achieved a mean accuracy of 89.96% (central range: 88.21%-90.95%), confirming the fundamental effectiveness of KANConv in feature extraction. However, its standalone application showed limitations in comprehending feature variations under complex operating conditions. The integration of the ACGCA module (KANConv-ACGCA) significantly improved mean accuracy to 96.03% (central range: 95.31–96.63%), with a narrower range indicating enhanced stability. This improvement verifies that our dual-branch attention module effectively strengthens feature representation through context-aware discrepancy analysis and non-local feature correlation learning.

The KANConv-SENet configuration attained a mean accuracy of 93.77% (central range: 92.35–94.85%), suggesting that the SENet successfully emphasizes critical features through channel-wise recalibration. However, its performance gain was less pronounced compared to ACGCA, supporting our proposition that global feature enhancement requires synergistic integration with local discrepancy detection for optimal results.

The full model (KANConv-ACGCA-SENet) achieved state-of-the-art performance with a mean accuracy of 99.02% (central range: 98.92–99.12%), exhibiting an exceptionally compact high-accuracy distribution without outliers. These findings reveal synergistic enhancement effects among the three components: KANConv provides adaptive nonlinear feature extraction, while ACGCA constructs comprehensive global representations, and SENet dynamically highlights critical fault features via channel-wise weighting. The organic integration of these modules enables robust stability and superior discriminative capability for detecting subtle fault feature under varying operational scenarios.

Conclusion

The advent of KANs has prompted a considerable amount of discourse within the domain of deep learning, and it has provided a novel and innovative direction for bearing fault diagnosis, which has generally relied on conventional CNNs. This paper proposes a bearing fault diagnosis model based on KANConv and ACGCA-SENet, which addresses the limitations of existing convolutional neural networks in linear convolution kernels and addresses the problem of focusing on specific features while neglecting others of equal importance. The method optimizes the structure of the bearing fault diagnosis model based on convolutional neural networks with KANs. It also proposes the ACGCA module, which employs a dual-branch fusion attention mechanism to comprehensively represent bearing fault features and which are then subjected to further emphasis through SENet.

This paper compares KAS with MTL-CWT-LSTM, MTF-Resnet, VMD-CNN, CNN-LSTM, TCN-KAN, and improved 2DCNN to confirm the superiority of this method. The experimental results demonstrate that KAS is an effective and comprehensive approach for focusing on bearing fault feature signals and accurately identifying differences in fault features. This significantly enhances the fault diagnosis performance of the model and its generalizability under variable operating condition scenarios.

To address the superimposed effects of multiple faults faced by bearings in real-world complex working environments, future research should focus on composite fault diagnosis across devices and operating conditions. For instance, adaptive optimization algorithms could be developed to enable models to perform automatic tuning and continuous learning under dynamic conditions. Additionally, multi-task learning mechanisms could be designed to integrate fault detection, classification, and severity assessment into a unified framework, thereby enhancing the practicality and effectiveness of diagnostic models.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, Z. et al. A deep learning method for bearing fault diagnosis based on cyclic spectral coherence and convolutional neural networks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 140, 106683 (2020).

He, D. et al. Train bearing fault diagnosis based on multi-sensor data fusion and dual-scale residual network. Nonlinear Dyn. 111(16), 14901–14924 (2023).

Ruan, D. et al. CNN parameter design based on fault signal analysis and its application in bearing fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 55, 101877 (2023).

Jia, L., Chow, T. W. & Yuan, Y. GTFE-Net: A gramian time frequency enhancement CNN for bearing fault diagnosis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105794 (2023).

Udmale, S. S. et al. An optimized extreme learning machine-based novel model for bearing fault classification. Expert. Syst. 41(2), e13432 (2024).

Jin, L., Zhi-Guo, W. & Fei, L. Rolling bearing variable load fault diagnosis based on STFT-ECAResNet18 Network Model. Noise Vib. Control 44(2), 122 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 11534–11542 (2020).

Yu, Z., Zhang, C. & Deng, C. An improved GNN using dynamic graph embedding mechanism: A novel end-to-end framework for rolling bearing fault diagnosis under variable working conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 200, 110534 (2023).

Xue, Y. et al. A novel framework for motor bearing fault diagnosis based on multi-transformation domain and multi-source data. Knowl. Based Syst. 283, 111205 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Semi-supervised meta-path space extended graph convolution network for intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under time-varying speeds. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safety 251, 110363 (2024).

Zhou, Q. et al. Bearing fault diagnosis for variable working conditions via lightweight transformer and homogeneous generalized contrastive learning with inter-class repulsive discriminant. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 139, 109548 (2025).

Udmale, S. S., Singh, S. K. & Bhirud, S. G. A bearing data analysis based on kurtogram and deep learning sequence models. Measurement 145, 665–677 (2019).

Nath, A. G. et al. Structural rotor fault diagnosis using attention-based sensor fusion and transformers. IEEE Sens. J. 22(1), 707–719 (2021).

Udmale, S. S., Nath, A. G. & Singh, S. K. Application of industry 4.0 and meta learning for bearing fault classification. In 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD) 1455–1460 (IEEE, 2022).

Liu, Z. et al. KAN: Kolmogorov–Arnold networks. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19756 (2024).

Abbasi, M. A., Huang, S. & Khan, A. S. Fault detection and classification of motor bearings under multiple operating conditions. ISA Trans. 156, 61–69 (2025).

Ji, L. et al. An intelligent diagnostic method of ECG signal based on Markov transition field and a ResNet. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 242, 107784 (2023).

Huang, T. et al. A novel fault diagnosis method based on CNN and LSTM and its application in fault diagnosis for complex systems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55(2), 1289–1315 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Understanding and learning discriminant features based on multiattention 1DCNN for wheelset bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 16(9), 5735–5745 (2019).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2(5), 359–366 (1989).

Pinkus, A. Approximation theory of the MLP model in neural networks. Acta Numer. 8, 143–195 (1999).

Wang, K. et al. Generative adversarial networks: Introduction and outlook. IEEE CAA J. Autom. Sin. 4(4), 588–598 (2017).

Kolmogorov, A. N. On the representation of continuous functions of many variables by superposition of continuous functions of one variable and addition. In Doklady Akademii Nauk. Vol. 114. 5. Russian Academy of Sciences 953–956 (1957).

Kolmogorov, A. N. On the Representation of Continuous Functions of Several Variables by Superpositions of Continuous Functions of a Smaller Number of Variables (American Mathematical Society, 1961).

Braun, J. & Griebel, M. On a constructive proof of Kolmogorov’s superposition theorem. Constr. Approx. 30, 653–675 (2009).

Xu, K., Chen, L. & Wang, S. Kolmogorov–Arnold networks for time series: Bridging predictive power and interpretability. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02496 (2024).

Cheon, M. Demonstrating the efficacy of Kolmogorov–Arnold networks in vision tasks. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.14916 (2024).

Cheon, M. & Mun, C. Combining KAN with CNN: KonvNeXt’s performance in remote sensing and patent insights. Remote Sens. 16(18), 3417 (2024).

Vaca-Rubio, C. J. et al. Kolmogorov–Arnold networks (KANs) for time series analysis. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08790 (2024).

Genet, R. & Inzirillo, H. Tkan: Temporal Kolmogorov–Arnold networks. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07344 (2024).

Koenig, B. C., Kim, S. & Deng, S. KAN-ODEs: Kolmogorov–Arnold network ordinary differential equations for learning dynamical systems and hidden physics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 432, 117397 (2024).

Shukla, K. et al. A comprehensive and FAIR comparison between MLP and KAN representations for differential equations and operator networks. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02917 (2024).

Karniadakis, G. E. et al. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3(6), 422–440 (2021).

Bodner, A. D. et al. Convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13155 (2024).

Fey, M. et al. Splinecnn: Fast geometric deep learning with continuous b-spline kernels. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 869–877 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Elevator fault diagnosis based on digital twin and PINNs-e-RGCN. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 30713 (2024).

He, K. et al. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 37(9), 1904–1916 (2015).

Liu, W., Salzmann, M. & Fua, P. Context-aware crowd counting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 5099–5108 (2019).

Xiang, X. et al. AGCA: An adaptive graph channel attention module for steel surface defect detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–12 (2023).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

Zhou, D. et al. Rethinking bottleneck structure for efficient mobile network design. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 16 680–697 (Springer, 2020).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7132–7141 (2018).

Jin, X. et al. Delving deep into spatial pooling for squeeze-and-excitation networks. Pattern Recognit. 121, 108159 (2022).

Loparo, K. Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Centre Website (2012).

Mao, A., Mohri, M. & Zhong, Y. Cross-entropy loss functions: Theoretical analysis and applications. In International Conference on Machine Learning 23803–23828 (PMLR, 2023).

Funding

The “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang Province, China (No. 2023C01022). The LingYan Planning Project of Zhejiang Province, China (No. 2023C01215). The Science and Technology Key Research Planning Project of HuZhou city, China (NO.2022ZD2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. designed the study and received funding for the project, approved the final manuscript as submitted. C.Y. conducted model training, validation and experiments, drafted and revised the manuscript. K.S. and J.L. collected data, analyzed and discussed the results. Q.T. evaluates the experiment. G.L. and H.Z reviewed the manuscript and gave comments. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Yin, C., She, K. et al. Bearing fault diagnosis for variable operating conditions based on KAN convolution and dual branch fusion attention. Sci Rep 15, 21442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04620-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04620-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A class-incremental learning method for fault diagnosis based on the CKAN-KAN: a case study on bearing faults

Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing (2026)