Abstract

The incorporation of both spatial and temporal characteristics is vital for improving the predictive accuracy of photovoltaic (PV) power generation forecasting. However, in multivariate time series forecasting, an excessive number of features and traditional decomposition methods often lead to information redundancy and data leakage, resulting in prediction bias. To address these limitations, this study introduces the Time-Embedding Temporal Convolutional Network (ETCN), providing an innovative solution. The ETCN model follows three key steps: First, a heatmap-based feature selection method identifies and prioritizes the most influential features, enhancing performance and reducing computational complexity. Second, a novel embedding architecture using multi-layer perceptrons captures both periodic and non-periodic information. Finally, a fusion strategy integrates spatial and temporal features through a DCNN with residual connections and BiLSTM, enabling effective modeling of complex data relationships. The ETCN model achieved outstanding performance, with RMSE, MAE, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) values of 0.5683, 0.3388 and 0.9439, respectively, on the Trina dataset. On the Sungrid dataset, the model achieved top results of 0.1351, 0.0964 and 0.9894, further demonstrating its superior accuracy across both datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solar energy, a sustainable and scalable alternative energy source with clean and versatile features, can meet the growing energy needs of humanity1,2. Unlike traditional energy sources such as hydropower or oil fired power, which can quickly adjust power generation to meet grid demand, photovoltaic power generation relies on high-precision forecasting due to the uncertainty and intermittency of sunlight, which poses significant challenges to the existing grid3,4,5,6. However, compared to long-term forecasting, short-term prediction can provide much more accurate and timely results.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence technology, machine learning based solar irradiance prediction models have superior performance compared to traditional physics and statistical methods7,8. Initially, predictions relied mainly on single-model approaches such as artificial neural network (ANN)9,10, support vector machine (SVM)11,12, and various deep learning models (see Table 1 for abbreviations). Among them, ANN performs in capturing the dynamic nature of solar power, but has limitations such as gradient vanishing and explosion. SVM has limitations in high computational complexity and difficulty in effectively processing large datasets. As deep learning technologies have evolved, significant progress has been made in photovoltaic power prediction. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs)13 and LSTM14,15,16,17,18 are adept at extracting information from sequential data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Time Convolutional Networks (TCN)19 are effective for spatial data analysis, which helps to understand the spatial dependence in photovoltaic power generation output. However, each model type has its limitations. RNNs and LSTMs can struggle with capturing spatial correlations effectively, while CNNs and TCNs may not handle temporal dependencies as efficiently. Therefore, combining these models is a good choice that can complement and improve overall performance.

For example, integrating LSTM units with simple CNN architectures has become one of the most common strategies for expanding the receptive field and improving prediction accuracy20,21,22,23,24,25. Beyond this typical approach, other hybrid models have also been developed to further enhance forecasting capabilities. For instance, Zhang et al. introduced a novel photovoltaic power forecasting model that combines variational mode decomposition with a CNN-BiGRU architecture26. Similarly, Geng et al. proposed a WDCNN-BiLSTM based hybrid PV/wind power prediction method, marking the first application of the WDCNN model in this field27. Ma and Mei took a different approach by combining Time2Vec, CNN, and stacked BiLSTM networks, incorporating an attention mechanism to enhance predictive performance further28. The IEDN-RNET model, introduced by Mirza, combines the ResNet and Inception modules with BiLSTM to effectively capture complex temporal patterns, achieving an average MAE of 16% and demonstrating superior performance in this domain29. These studies highlight the ongoing evolution of hybrid models, emphasizing the potential of combining traditional and cutting-edge techniques to further refine the precision and reliability of forecasting systems in various domains30.

In addition, the inherent randomness and intermittency present in the raw sequences of time series data often lead to suboptimal forecasting outcomes, as illustrated in Fig. 1. To address this challenge, signal decomposition methods can divide unstable sequences into stable subsequences and reconstruct their predicted values, which reduces the computational complexity while enhancing the accuracy of photovoltaic power predictions31, such as wavelet decomposition, wavelet packet transform32,33,34, ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD)35,36,37,38,39, and variational mode decomposition (VMD)40. However, data decomposition is typically conducted before partitioning the dataset into training and test subsets, a practice that entails a potential risk of information leakage. Therefore, a new method is needed to effectively extract both periodic and non-periodic hidden patterns.

In this paper, a novel hybrid deep learning model tailored for photovoltaic (PV) power prediction is developed to address prior concerns. Specifically, the proposed model can enhance the spatiotemporal distinguishability of window size and alleviate the rapid forgetting of historical information. Therefore, the Time-Embedding Temporal Convolutional Network (ETCN) model is introduced, in which positional coding is employed to impart spatial and temporal identification to the window. Additionally, a residual module is integrated into the conventional DCNN architecture to decelerate the decay of historical information. The contribution of this paper is presented as follows:

-

(1)

An effective feature selection method based on thermal maps is proposed, which can select key factors from a wide range of environmental factors as input variables for the model.

-

(2)

A novel embedding architecture combining multilayer perceptron is designed to extract periodic and non-periodic hidden information to solve data leakage problem.

-

(3)

An effective fusion strategy is proposed to combine temporal features from BiLSTM and spatial features from residual DCNN in parallel mode to maximize the capability of a single model.

-

(4)

The proposed method enhances the accuracy of photovoltaic power prediction and improves the ability to capture sudden fluctuations, thereby mitigating the issues caused by the inherent intermittency and uncontrollability of photovoltaic systems.

The paper is structured as follows: Section “Framework” details the correlation analysis and the architecture of the ETCN. Section “Experimental setup, dataset description, and evaluation metrics” provides an overview of the implementation details, dataset description, and evaluation metrics. In “Performance study” Section, we present the model’s hyperparameters, experimental case studies, and model assessment. Section 5 discusses the advantages and limitations of our study. Finally, Section 6 offers a concise conclusion.

Framework

Preliminary

Solar energy production is closely associated with meteorological conditions, which result in fluctuations in photovoltaic (PV) power output. The proposed architecture, referred to as ETCN and illustrated in Fig. 2, consists of three primary stages: input reconstruction, feature extraction, and feature mapping. The ETCN model integrates both meteorological and historical data, represented mathematically as \(X = (\mathbf {x_1}, \mathbf {x_2}, ..., \mathbf {x_n})^\textrm{T} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times l}\), where l denotes the size of a time window. Here \(\mathbf {x_t} = (x_{t1}, x_{t2}, ..., x_{tn})^\textrm{T} \in \mathbb {R}^n\) represents meteorological information at time t and \(\mathbf {x_k} = (x_{k1}, x_{k2}, ..., x_{kl})^\textrm{T} \in \mathbb {R}^l\) represents the k-th meteorological factor over an l time steps window. Besides current meteorological data, historical PV data is also considered, forming part of the input. Thus, the forecasting equation is

Initially, data undergoes correlation analysis to select highly correlated features for input. Subsequently, an embedding layer supplements periodic and non-periodic information. Feature extraction involves capturing spatial and temporal patterns using a parallel structure to extract expressive features. Finally, these features are utilized to predict future PV output.

Input reconstruction

Correlation analysis between meteorological factors and PV power

The Desert Knowledge Australia Solar Center (DKASC), particularly the Alice Springs station, stands out as a valuable source of photovoltaic (PV) power data for research purposes. In comparison to other datasets, DKASC offers comprehensive and reliable data on key features such as Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI)41,42, thus demonstrating its superiority for conducting robust analyses and forecasting solar energy generation. The recorded data in this system consists of historical measurements of active power as well as various weather conditions such as wind speed, atmospheric temperature, relative humidity, global horizontal radiation, and diffuse horizontal radiation. The accuracy of a model can be enhanced by using many relevant inputs which are highly dependent on local weather conditions. The correlation analysis is calculated through Eq. (1) between various environmental factors and power data.

where \((f_i,p_i)\) represents the sample taken from \((f,p), i=1,2,3,\dots ,n\); The correlation coefficient between PV power and various environmental factors is shown in Fig. 3. All parameters are listed and described as shown in Table 1.

By observing the correlation between variables through the visualization provided by a thermodynamic diagram, as depicted in Fig. 3. The positive correlation between photovoltaic power and active energy delivered received is the highest followed by global horizontal radiation, diffuse horizontal radiation, weather relative humidity, weather temperture celsius and wind speed. There is little correlation between photovoltaic power and wind direction and others. When the correlation is below 0.2, it is generally considered that there is virtually no relationship between the two features43. After completing the feature selection process, the features are represented as \(f_i \in \mathbb {R}^M\).

Position embedding

The embedding layer consists of periodic and non-periodic embedding, which capture cyclic patterns and encode non-cyclic features, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4. These two steps are used to derive the temporal identity \(T_t\), which is first encoded through periodic embedding as shown in Eq. 2.

Then, the encoded temporal identity \(t_{\text {periodic}}\) is passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to obtain the final temporal embedding,as shown in Eq. 3.

By these two operations map the historical time series \(X_{t-P:t}^{i}\), spanning a window of length \(P\), to a latent space \(T_t \in \mathbb {R}^D\), where \(D\) represents the hidden dimension of the latent space. Subsequently, the meteorological and temporal identities (denoted as \(f_i\) and \(T_t\), respectively) are concatenated to form the hidden representation \(Z_t^i \in \mathbb {R}^{D+M}\).

Feature extraction

Long short-term memory and bidirectional long short-term memory network sub-component

LSTM excels at handling sequence-based problems by leveraging a hidden state \(h_t\), a cell state \(c_t\), and three gates: the forget gate, input gate, and output gate, as illustrated in Fig.5. The sequence of operations for an LSTM unit is as follows:

where \(W_f\), \(W_i\), \(W_o\), \(W_c\), \(b_f\), \(b_i\), \(b_o\), and \(b_c\) are the trainable weights and biases, and \(\sigma\) denotes the sigmoid activation function for the gates. Combining all operations, an LSTM unit can be expressed as a nonlinear function \(f\):

Generally, due to the inherent limitation of LSTM in processing information in a single direction, it struggles to capture context from both past and future time steps. BiLSTM addresses this limitation by processing information bidirectionally, enabling the model to effectively capture context from both directions, as depicted in Fig. 6. This bidirectional approach enhances the model’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, thereby improving stability and performance, particularly for volatile sequences, as described by the output equation in Eq. 6.

where \(\text {LSTM}(\cdot )\) denotes the traditional LSTM function, as shown in Eq.4. Here, \(W_h^f\) and \(W_h^b\) are the weight matrices for the forward and backward hidden sequences, respectively, and \(b\) represents the bias term in the output layer of the BiLSTM. The BiLSTM architecture is designed to extract more comprehensive temporal features by processing information in both the “forward” and “backward” directions.

Residual DCNN sub-component

The DCNN subcomponent incorporates two essential mechanisms: dilated convolutions and residual connections. These mechanisms efficiently expand the receptive field while preserving critical details of the original information. By leveraging Residual DCNN sub-component for spatial feature extraction, the model is better equipped to capture long-term dependencies. A detailed illustration of the sub-component’s structure is provided in Fig. 7.

A. Dilated convolutions To overcome the limitation of CNNs’ constrained receptive field, the proposed method introduces the architecture of dilated convolutional neural networks (DCNN). This architectural enhancement aims to augment the spatial feature extraction process through the integration of dilated convolutions. Unlike conventional convolutions, dilated convolutions incorporate gaps or skips between kernel elements. These gaps enable the network to access a broader receptive field without necessitating an increase in the layer count. Through the application of dilated convolutions to the input series, the DCNN is capable of more effectively capturing long-term characteristics and dependencies.

B. Residual connections The primary objective of the residual block44 is to mitigate the risk of information loss and distortion inherent in deep convolutional networks following traversal through multiple layers. This objective is accomplished through a sequence of operations, as demonstrated by the following equation:

This formulation allows the network to retain crucial input information by learning residual mappings, thereby facilitating more stable gradient flow and improving the overall training efficiency of deep convolutional networks.

Feature mapping

Feature mapping is used to transform spatiotemporal features into higher-dimensional representations through a structure consisting of an input layer, hidden layer, and output layer. Trained to forecast PV generation, its nonlinear learning ability efficiently handles multi-dimensional inputs and captures complex data relationships.

Experimental setup, dataset description, and evaluation metrics

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the implementation details, datasets utilized, and evaluation metrics employed.

Implementation details

The experiments were conducted utilizing a computational infrastructure comprising an NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPU, and the PyTorch framework version 2.0.1 was employed for implementation.

During model training, parameters were initialized using the Kaiming distribution, a popular technique for deep learning models. The Adam optimizer was utilized for parameter optimization, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001. If the validation loss stagnated over an extended period, the learning rate was decreased by a factor of ten. To prevent overfitting, the early stopping strategy was employed, halting the training process when the model’s performance on a separate validation set no longer improves.

Dataset description

The Desert Knowledge Australia Solar Center (DKASC) stands as a distinguished solar research facility situated in Alice Springs, Australia. This esteemed establishment furnishes valuable insights into prevailing weather conditions, thereby facilitating the comprehension and prediction of weather patterns. The repository of climate data encompasses a diverse array of parameters, including fundamental atmospheric metrics such as temperature and wind speed, alongside less conventional indicators like global horizontal radiation.

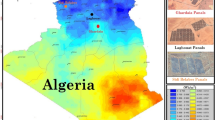

The Map of Alice Springs and site locations of PV sites.45.

To gauge the efficiency and robustness of the ETCN model, datasets from No. 1A Trina and No. 19 Sungrid are selected for analysis and verification. These datasets offer a rich source of historical information essential for understanding the dynamics of solar power generation. Notably, the varying installation methods adopted by the power stations significantly influence their solar energy capture capabilities.

The geographic coordinates of the PV power plants in Fig. 8 intuitively show their spatial locations. Additionally, the detailed specifications of the power stations provided in Table 2 offer comprehensive insights into their configurations and operational parameters.

Evaluating indicator

For evaluating the performance of different models, the MAE (mean absolute error), RMSE (root mean square error), and R2 (R-squared) are employed as evaluation criteria. These metrics provide a quantitative assessment of the model’s accuracy and predictive power. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where T represents the number of prediction points, \(y_i\) represents the real power value of the \(i^{th}\) time point, \(\hat{y}_i\) represents the predicted value of the corresponding model, and \(\bar{y}_i\)denotes the mean value of \(y_i\).

The RMSE provides a measure of the model’s stability, with a lower RMSE indicating a more stable model. Conversely, the metric assesses the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model. A higher \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) value suggests greater predictive power, especially in capturing fluctuations such as peaks and troughs in the data.

In addition to these metrics, the Skill Score (SS) is often used to compare the performance of the predictive model against a baseline model, typically a persistence model. The Skill Score is defined as:

where RMSE represents the Root Mean Square Error of the predicted model, while \(\text {RMSE}_{b}\) denotes the RMSE value for the baseline reference model. The SS is calculated as follows: an SS of 100% indicates perfect prediction accuracy, while an SS of 0% suggests that the performance of the evaluated model (RMSE) is equivalent to that of the baseline model (\(\text {RMSE}_b\)). Negative values of SS imply that the baseline reference model outperforms the predicted model.

Performance study

A series of experimental studies were conducted to assess the efficiency of the ETCN model. The experiments include detailed setup descriptions, benchmark models for comparison, experimental results, and corresponding analyses.

Dimension of embedding layer

In this section, the influence of the embedding layer’s undetermined dimensions on the model’s performance is thoroughly examined through a meticulous comparative analysis. Through comparative experiments on the Trina dataset, the effects of varying embedding layer dimensions on both the learning process and the model’s representation capabilities are scrutinized.

The Fig. 9 illustrates the relationship between dimensionality and the model’s ability. Initially, increasing dimensionality decreases model’s ability, followed by a subsequent improvement. However, excessive dimensionality would lead to information redundancy within the model architecture.

Notably, a dimensionality of 4 emerges as the optimal hyperparameter choice. This dimensionality enhances the model’s proficiency in discerning intricate data patterns while mitigating the risk of information overload. Additionally, it reduces the number of trainable parameters, thereby improving computational efficiency.

Photovoltaic prediction on Trina site

This section presents an evaluation and comparison of the forecasting accuracy of the proposed ETCN model against various benchmark models using the Trina station dataset. The assessment is conducted using four distinct metrics, as outlined in Subsection 3.3, to provide a comprehensive analysis of the forecasting capabilities of both the ETCN model and the benchmark models.

The Trina station dataset, depicted in Fig. 10, features unique daily fluctuation frequencies in power generation. Data from the Trina site, spanning from August 15, 2013, to September 15, 2013, is used in our analysis. The dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets for the analysis. The final three days of the dataset are reserved for testing, while five days are set aside for validation, and the rest of the data was employed for training. The Dataset is sampled at 5-minute intervals.

The forecasting results, illustrated in Fig. 10 and summarized in Table 3, reveal notable performance disparities among the various predictive models evaluated. The first three columns represent the single models: LSTM, BiLSTM, and DCNN. Their performance metrics are as follows: LSTM records Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.5951, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.8877, an R-squared (\(\hbox {R}^{2}\) ) value of 0.8591, SS value of 59.04%. The BiLSTM model shows improvement, with lower MAE of 0.4052 and RMSE of 0.6597, obtains higher \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) score and higher SS value. The DCNN model’s archieves metrics of MAE at 0.5776, RMSE at 0.8795, the \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) 0.8655, and SS at 59.42%.. The last three columns represent hybrid models, which integrate features from different models: DCNN_LSTM, DCNN_BiLSTM, and ETCN. These hybrid models demonstrate significantly enhanced performance, highlighting the benefits of model fusion. Specifically, the DCNN_LSTM model achieves MAE of 0.3502, RMSE of 0.6106, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) of 0.9358. The DCNN_BiLSTM model further improves these results, with MAE of 0.3634, RMSE of 0.6002, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) of 0.9373. However, the ETCN model surpasses all others, with the lowest MAE (0.3388), RMSE (0.5683), and the highest \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) (0.9439) and SS (73.78%). These results underscore the ETCN model’s superiority in predictive accuracy and model fit, outperforming both single models and other hybrid models on the Trina Cells dataset.

In summary, the forecasting errors were mitigated through more accurate scheduling of power generation resources, leading to improved grid performance. While the model demonstrated strong performance in several aspects, certain limitations were observed. Specifically, between time steps 305 and 400, none of the models successfully captured the continuous downward fluctuation. Although our model detected a slight trend of this fluctuation, it was unable to precisely predict the depth of these variations. This discrepancy suggests that an unaccounted-for factor-potentially an obstruction to sunlight-may have contributed to the reduction in energy output. The delayed influence of this factor on the data is likely due to the complex and time-dependent nature of its impact. A review of the climate data for this period did not reveal any immediate indicators of fluctuations, raising the possibility that cloud cover or other environmental factors may have caused these anomalies. This highlights the importance of considering additional variables, such as cloud cover, in future model refinements to improve prediction accuracy.

Photovoltaic prediction Sungrid site

To further assess the generalization capabilities of the proposed model, the analysis is extended to the Sungrid dataset, covering the period from April 14, 2014, to May 14, 2014. In a manner consistent with the approach applied to the Trina dataset, the Sungrid dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets. The final three days are designated as test data, with five days reserved for validation, while the remainder constituted the training dataset. The dataset is also sampled at 5-minute intervals. It is important to note that the days within the test period show considerable variability, with the first day being significantly more volatile than subsequent days. This also makes forecasting more difficult. The experimental findings are presented in Fig. 11 and Table 4.

Based on the values presented, it can be deduced that the ETCN model outperforms the others across all metrics. The MAE of ETCN is the lowest at 0.0964, indicating that on average, the ETCN model has the smallest absolute error in its predictions. The RMSE, which gives a sense of the magnitude of error, is also lowest for ETCN at 0.1351. Finally, the \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) value for ETCN is the highest at 0.9894, suggesting that it explains a higher proportion of the variance in the data compared to the other models. In addition, ETCN achieved the highest SS of 83.55%, outperforming the second-best model by a margin of 3%, further demonstrating its superior capability in PV power forecasting. Based on the results, it can be concluded that the model performs exceptionally well for the Sungrid system, despite the challenges posed by its suboptimal installation method. The reduction in forecasting errors demonstrates that the ETCN model is applicable to a wide range of solar power stations with different installation configurations, proving its broad applicability. A similar issue is observed between Tim 150 and Tim 180, where a sharp fluctuation is evident. In contrast, the meteorological data before and after this period remain relatively stable. This stark discrepancy raises concerns that the observed fluctuation may be an outlier or anomaly, potentially resulting from a data error or an external factor not accounted for in the model.

Photovoltaic on different horizon-step

In this section, the correlation between the horizon step and predictive capacity is explored. In order to verify the validity and accuracy of the model ETCN proposed in this paper, other models including LSTM, BiLSTM, DCNN, DCNN-BiLSTM are considered. The multi-step prediction model results of different model in 3-step (15 min), 5-step (25 min), and 7-step (35min) are displayed in Table 5.

The data in Table 5 provides a detailed comparison of the performance metrics for the ETCN model and benchmark models (LSTM, BiLSTM, DCNN, DCNN_LSTM, and DCNN_BiLSTM) across various prediction steps at the Trina Station. The ETCN model consistently outperforms the others with the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and highest R-squared (R2) values. For instance, at a prediction step of 3, the ETCN model achieves MAE of 0.5054, RMSE of 0.8371, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) score of 0.8758, outperforming all other models, including the next best DCNN_BiLSTM model which has MAE of 0.5253, RMSE of 0.8728, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) of 0.8664. As the prediction step increases to 7, the ETCN model maintains its superior performance with MAE of 0.6595, RMSE of 1.0526, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) of 0.7977, again leading over the other models, where the closest competitor, the BiLSTM model, records MAE of 0.6853, RMSE of 1.0525, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) of 0.7978. These consistent results across all horizon steps clearly demonstrate the superior predictive capacity and robustness of the ETCN model compared to the other models evaluated in this study.

Ablation study

In this study, an ablation experiment is conducted to evaluate the individual contributions of various components of the model, including feature selection, position embedding, the BiLSTM sub-component, and the residual DCNN sub-component, to the overall performance. The results suggest that each component contributes significantly to enhancing the model’s predictive accuracy, as summarized in Table 6. Specifically, the BiLSTM component alone achieved an MAE of 0.3953 and an RMSE of 0.6752, demonstrating baseline performance. Introducing feature selection slightly increased the MAE to 0.4052 but improved the \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) value to 0.9236. The addition of position embedding further reduced MAE to 0.3856 and RMSE to 0.6330, enhancing the model’s overall performance. Incorporating residual DCNN led to a notable improvement, with MAE decreasing to 0.3634 and RMSE to 0.6002. Both residual DCNN and position embedding contribute complementary information to the model from distinct dimensions. Residual DCNN, with its capacity to capture local patterns and hierarchical feature representations, enriches the model by extracting spatially dependent features, thus improving its ability to discern intricate relationships within the data. On the other hand, position embedding offers essential context by encoding the sequential or spatial ordering of input elements, which helps the model understand positional dependencies and relative relationships. When integrated into the model, these two components work synergistically. The residual DCNN enhances the model’s feature extraction capabilities, while the position embedding provides crucial positional information. Together, they significantly contribute to the overall performance improvement across multiple evaluation metrics. The model achieved the best results, with MAE of 0.3388, RMSE of 0.5683, and \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) value of 0.9439, which further confirms the effectiveness of combining these features.

Discussion

In this study, a novel hybrid forecasting architecture, ETCN, is proposed for short-term photovoltaic forecasting. This model introduces three key advancements that distinguish it from existing approaches, offering clear benefits in both performance and interpretability.

First, a heatmap-based feature selection method is designed to identify the most influential features to improve model performance and precision. Unlike traditional models that uniformly process all input variables, our approach systematically identifies and prioritizes the most influential features by visualizing their correlations through heatmaps. This methodology not only improves the transparency of the model’s decision-making process but also allows for more precise adjustment of input variables, which mitigates the computational burden and alleviates learning complexity, ultimately leading to enhanced prediction accuracy.

In addition, a novel embedding architecture is introduced that integrates multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) to extract both periodic and non-periodic hidden information. This design allows the model to capture a broader range of data patterns compared to conventional methods. Most existing models rely on decomposition techniques to extract information from raw data, during which data leakage can occur. The proposed method addresses this limitation by employing alternative techniques to extract information through the embedding layer and directly integrating it with the filtered features, which are then reconstructed as new inputs. This approach enhances the model’s ability to recognize patterns and adapt effectively. Photovoltaic power generation, being inherently complex, benefits from this improved methodology.

Furthermore, an effective fusion strategy is developed to seamlessly integrate the spatial and temporal feature. Our architecture employs a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) with residual connections to capture spatial features across an expansive receptive field, which is crucial for identifying patterns within large data sequences. Concurrently, a BiLSTM component is used to extract meaningful temporal dependencies from different directions, ensuring that the model fully leverages the sequential nature of the data. This parallel processing is not only about combining different types of features; it strategically leverages the strengths of each component while mitigating their weaknesses. This careful balance and thoughtful integration of techniques enhances our model’s ability to achieve a more precise interpretation of the data. As a result, the model’s resilience is enhanced under challenging conditions, such as extreme weather events or when making predictions across multiple time horizons.

Finally, The proposed method enhances photovoltaic power prediction by better capturing fluctuations for the factors, with weather and time of day. By integrating real-time weather data with historical output, forecast accuracy is significantly enhanced.This allows for more reliable short-term predictions, helping grid operators manage power fluctuations and ensuring backup resources when solar output drops. Ultimately, it improves grid stability, supports efficient energy distribution, and aids the integration of photovoltaic power into the energy system.

In conclusion, the ETCN model’s innovative design and strategic integration of advanced methodologies offer substantial improvements over existing models. Its ability to optimize feature selection, integrate spatial and temporal features, and effectively utilize new features results in a model that is not only more accurate but also more robust and interpretable, providing significant advantages in the field of PV power forecasting. The model may still exhibit certain limitations in accurately forecasting extreme events. There are still many unconsidered factors, such as cloud cover or equipment malfunctions. Introducing sky maps could potentially help reduce some of these errors.

Conclusion

In this study, the hybrid forecasting architecture is proposed to enhance predictive accuracy while addressing the issue of data leakage associated with traditional decomposition methods used to capture periodic and non-periodic information.By optimizing and integrating diverse data features, the model significantly improves forecasting accuracy and timeliness, thereby enabling more efficient energy allocation. This, in turn, helps reduce the need for excessive energy reserves and enhances grid stability, positioning the ETCN model as a valuable tool for modern renewable energy systems. Its ability to tackle these challenges underscores its potential to advance forecasting capabilities and improve overall operational efficiency within the renewable energy sector.

However, the model has some limitations. The complexity of the architecture may lead to increased computational demands, particularly during the training phase, which could be a challenge when applied to larger datasets. Moreover, the model fails to identify outliers, and the algorithm lacks preliminary measures to handle these anomalies, preventing them from being excluded from the subsequent forecasting process.

Future work should focus on optimizing the model’s computational efficiency to make it more suitable for large-scale applications. Furthermore, research could explore strategies for outlier detection and handling, such as incorporating anomaly detection mechanisms or preprocessing techniques, to ensure cleaner data input and improve forecasting accuracy. These improvements would enhance the model’s overall reliability and adaptability to diverse real-world scenarios.

Data availability

The experimental data used in this study is sourced from the Desert Knowledge Australia (DKA) Solar Centre (https://dkasolarcentre.com.au/). The authors express their sincere gratitude to DKA for providing access to this data. Access to the data may require approval and can be requested directly from the DKA Solar Centre through their official channels. For further inquiries regarding the data, please contact Jingxin Wang at wangjx2022@shanghaitech.edu.cn.

Change history

04 September 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article contained errors. It now reads: “This work was sponsored by Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2021289) and Fujian Science and Technology Program (2023T3020).”

Abbreviations

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory

- DCNN:

-

Dilated convolutional neural network

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural network

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- RNN:

-

Recurrent neural network

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- TCN:

-

Time convolutional network

- EEMD:

-

Ensemble empirical mode decomposition

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- \(\hbox {R}^{2}\) :

-

R square

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- VMD:

-

Variational mode decomposition

- WDCNN:

-

Deep convolutional neural network with wide first-layer kernel

References

Ahmed, R., Sreeram, V., Mishra, Y. & Arif, M. D. A review and evaluation of the state-of-the-art in PV solar power forecasting: Techniques and optimization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 124, 109792 (2020).

Malhan, P. & Mittal, M. A novel ensemble model for long-term forecasting of wind and hydro power generation. Energy Convers. Manag. 251, 114983 (2022).

Guermoui, M., Melgani, F., Gairaa, K. & Mekhalfi, M. L. A comprehensive review of hybrid models for solar radiation forecasting. J. Clean. Prod. 258, 120357 (2020).

Wang, K., Qi, X. & Liu, H. Photovoltaic power forecasting based LSTM-Convolutional Network. Energy 189, 116225 (2019).

Zhang, C., Junjie Xia, X., Guo, C. H., Lin, P. & Zhang, X. Multi-optimal design and dispatch for a grid-connected solar photovoltaic-based multigeneration energy system through economic, energy and environmental assessment. Sol. Energy 243, 393–409 (2022).

Dutta, R., Das, S. & De, S. Multi criteria decision making with machine-learning based load forecasting methods for techno-economic and environmentally sustainable distributed hybrid energy solution. Energy Convers. Manag. 291, 117316 (2023).

Alcañiz Moya, A., Grzebyk, D., Ziar, H. & Isabella, O. Trends and gaps in photovoltaic power forecasting with machine learning. Energy Rep. 9, 447–471 (2022).

Wang, X., Sun, Y., Luo, D. & Peng, J. Comparative study of machine learning approaches for predicting short-term photovoltaic power output based on weather type classification. Energy 240, 122733 (2022).

Xue, X. Prediction of daily diffuse solar radiation using artificial neural networks. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42(47), 28214–28221 (2017).

Hussain, S. & AlAlili, A. A hybrid solar radiation modeling approach using wavelet multiresolution analysis and artificial neural networks. Appl. Energy 208, 540–550 (2017).

Wang, F., Zhen, Z., Wang, B. & Mi, Z. Comparative study on KNN and SVM based weather classification models for day ahead short term solar PV power forecasting. Appl. Sci. 8, 28, 12 (2017).

Pan, M. et al. Photovoltaic power forecasting based on a support vector machine with improved ant colony optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123948 (2020).

Gundu, V. & Simon, S. P. Short term solar power and temperature forecast using recurrent neural networks. Neural Process. Lett. 53(6), 4407–4418 (2021).

Ewees, A. A., Al-qaness, M. A. A., Abualigah, L. & Elaziz, M. A. HBO-LSTM: Optimized long short term memory with heap-based optimizer for wind power forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 268, 116022 (2022).

Wang, F. et al. A day-ahead PV power forecasting method based on LSTM-RNN model and time correlation modification under partial daily pattern prediction framework. Energy Convers. Manag. 212, 112766 (2020).

Ahmed, R., Sreeram, V., Togneri, R., Datta, A. & Arif, M. D. Computationally expedient Photovoltaic power Forecasting: A LSTM ensemble method augmented with adaptive weighting and data segmentation technique. Energy Convers. Manag. 258, 115563 (2022).

Memarzadeh, G. & Keynia, F. A new short-term wind speed forecasting method based on fine-tuned LSTM neural network and optimal input sets. Energy Convers. Manag. 213, 112824 (2020).

Huang, X. et al. Time series forecasting for hourly photovoltaic power using conditional generative adversarial network and Bi-LSTM. Energy 246, 123403 (2022).

Bai, S., Kolter, J. Z. & Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.01271 (2018).

Agga, A., Abbou, A., Labbadi, M. & El Houm, Y. Short-term self consumption PV plant power production forecasts based on hybrid CNN-LSTM, ConvLSTM models. Renew. Energy 177, 101–112 (2021).

Zhang, X., Chau, T. K., Chow, Y. H., Fernando, T. & Iu, H. H. A novel sequence to sequence data modelling based CNN-LSTM algorithm for three years ahead monthly peak load forecasting. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 39, 1932–1947 (2023).

Miraftabzadeh, S. M. & Longo, M. High-resolution PV power prediction model based on the deep learning and attention mechanism. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 34, 101025 (2023).

En, F., Zhang, Y., Yang, F. & Wang, S. Temporal self-attention-based Conv-LSTM network for multivariate time series prediction. Neurocomputing 501, 162–173 (2022).

Agga, A., Abbou, A., Labbadi, M., El Houm, Y. & Ali, I. H. O. CNN-LSTM: An efficient hybrid deep learning architecture for predicting short-term photovoltaic power production. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 208, 107908 (2022).

Tang, Y., Yang, K., Zhang, S. & Zhang, Z. Photovoltaic power forecasting: A hybrid deep learning model incorporating transfer learning strategy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 162, 112473 (2022).

Zhang, C., Peng, T. & Nazir, M. S. A novel integrated photovoltaic power forecasting model based on variational mode decomposition and CNN-BiGRU considering meteorological variables. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 213, 108796 (2022).

Geng, D., Wang, B. & Gao, Q. A hybrid photovoltaic/wind power prediction model based on Time2Vec, WDCNN and BiLSTM. Energy Convers. Manag. 291, 117342 (2023).

Ma, Z. & Mei, G. A hybrid attention-based deep learning approach for wind power prediction. Appl. Energy 323, 119608 (2022).

Mirza, A. F., Mansoor, M., Usman, M. & Ling, Q. Hybrid Inception-embedded deep neural network ResNet for short and medium-term PV-Wind forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 294, 117574 (2023).

Hassan, M. A., Al-Ghussain, L., Khalil, A. & Kaseb, S. A. Self-calibrated hybrid weather forecasters for solar thermal and photovoltaic power plants. Renew. Energy 188, 1120–1140 (2022).

Lin, W., Zhang, B. & Lu, R. Short-term forecasting for photovoltaic power based on successive variational modal decomposition and cascaded deep learning model. In 2023 6th International Conference on Energy, Electrical and Power Engineering (CEEPE) 1011–1016 (IEEE, 2023).

Almaghrabi, S., Rana, M., Hamilton, M. & Rahaman, M. S. Solar power time series forecasting utilising wavelet coefficients. Neurocomputing 508, 182–207 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Deep neural network for forecasting of photovoltaic power based on wavelet packet decomposition with similar day analysis. Energy 271, 126963 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Deep neural network for forecasting of photovoltaic power based on wavelet packet decomposition with similar day analysis. Energy 271, 126963 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Short-term wind speed predicting framework based on EEMD-GA-LSTM method under large scaled wind history. Energy Convers. Manag. 227, 113559 (2021).

Raj, N. & Brown, J. An EEMD-BiLSTM algorithm integrated with Boruta random forest optimiser for significant wave height forecasting along coastal areas of Queensland, Australia. Remote Sens. 13(8), 1456 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Accurate solar PV power prediction interval method based on frequency-domain decomposition and LSTM model. Energy 262, 125592 (2023).

Liu, Z., Sun, W. & Zeng, J. A new short-term load forecasting method of power system based on EEMD and SS-PSO. Neural Comput. Appl. 24, 973–983 (2014).

Prasad, R., Ali, M., Kwan, P. & Khan, H. Designing a multi-stage multivariate empirical mode decomposition coupled with ant colony optimization and random forest model to forecast monthly solar radiation. Appl. Energy 236, 778–792 (2019).

Liu, W., Bai, Y., Yue, X., Wang, R. & Song, Q. A wind speed forcasting model based on rime optimization based VMD and multi-headed self-attention-LSTM. Energy 294, 130726 (2024).

Sobri, S., Koohi-Kamali, S. & Rahim, N. A. Solar photovoltaic generation forecasting methods: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 156, 459–497 (2018).

Kumari, P. & Toshniwal, D. Analysis of ANN-based daily global horizontal irradiance prediction models with different meteorological parameters: A case study of mountainous region of India. Int. J. Green Energy 18(10), 1007–1026 (2021).

Wencheng, L. & Zhizhong, M. Short-term photovoltaic power forecasting with feature extraction and attention mechanisms. Renew. Energy 226, 120437 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition (2015).

Dka solar centre. 2024. Accessed: 2024-08-18.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2021289) and Fujian Science and Technology Program (2023T3020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingxin Wang: Conceptualized the research idea, designed the methodology, conducted the primary experiments, and led the overall project direction. Guohan Li: Managed data collection, preprocessing, contributed to key aspects of result analysis, and assisted in model validation and optimization. Jin Gu: Assisted with data organization, maintained experiment logs, and helped draft sections of the technical report. Zhengyi Xu: Assisted with data organization, managed experiment documentation, and contributed to sections of the manuscript and literature review. Xinrong Chen: Took the lead in analyzing and interpreting the results, played a significant role in drafting the manuscript, and contributed extensively to the literature review. Jianming Wei: Reviewed and revised the manuscript, provided critical insights, and ensured the technical accuracy of the content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Li, G., Gu, J. et al. Short term prediction of photovoltaic power with time embedding temporal convolutional networks. Sci Rep 15, 22400 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04630-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04630-z