Abstract

Sprinting actions are related to decisive moments of the match and impose severe fatigue levels on football players, and are often preceded by lower intensity running patterns or walking on the field. This study aimed to compare the effects of different exercise drills on speed and acceleration dynamics. Forty Under-19 and Under-23 soccer players participated in different sprint drill conditions, quantifying their distance covered in various speed intensities covering high-speed running and sprinting patterns and their peak acceleration. The speed drills were compared across different conditions: LS30m (30 m Linear Sprint), LS40m (40 m Linear Sprint), 15BR + LS30m (15 m Bounding Run + 30 m Sprint), 15BR + LS40m (15 m Bounding Run + 40 m Sprint), and CS30m (30 m Chasing Sprint). The results of this study showed significant differences regarding maximal acceleration between the lowest value 15BR + LS30m (5.62 ± 0.83 m/s2) and the highest, CS30m (7.09 ± 1.25 m/s2; p = 0.001; d = − 0.88), as well as with LS30m (6.98 ± 1.43 m/s2; p = 0.003; d = − 0.59), LS40m (6.76 ± 1.60 m/s2; p = 0.002; d = − 0.69) drill. Regarding Sprint 3 distance (distance covered > 95% of maximal speed) significant differences were found between the highest, LS40m (2.42 ± 4.82 m) and the lowest 15BR + LS30m (0.0 ± 0.00; p = 0.057; d = − 0.52) as well LS30m (0.90 ± 3.31 m; p = 0.017; d = − 0.37) drill. These results suggest that the capacity to reach peak acceleration is mediated by how the athlete approaches the linear sprint. Moreover, the LS40m was observed to be a drill that successfully exposes the athlete to their peak speed compared to the LS30m and 15BR + 30 m drills. Therefore, it should be considered the use of LS40m drill for training prescriptions for developing speed or hamstring conditioning. Finally, the CS30m drill exposed the athletes to the highest peak acceleration, probably due to the visual stimulus provided by the opponent, which might have elicited higher levels of motivation for the chasing player. Briefly, in the LS40m, athletes cover more distance above 95% of maximum speed, while the CS30m seems to be more effective for achieving higher accelerations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During competition, football players are exposed to high loads, including accelerations, decelerations, and displacements at different speeds1. Considering that the match-day is usually the most demanding day of the week (i.e., the microcycle)2,3, practitioners need to ensure that players are prepared to cope with these demands. Otherwise, players’ performance may be affected, and the injury risk could increase4,5. This challenge can be understood with the fitness-fatigue model, originally proposed by Bannister6, where a stimulus creates a certain amount of fatigue, which, with appropriate recovery, leads to enhanced performances7.

One of the greatest concerns among football players and coaches is muscle injuries, especially hamstring injuries8, the occurrence of which has been increasing 12% from the 2001/2002 season to the 2021/2022 season, constituting 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football9. Although the causes of these injuries are multifactorial, sprint displacements have been established as potentiators when performed in fatigue state10 and when players are not systematically exposed to maximal sprint efforts11. Here, a recent review12 has highlighted the necessity of exposing players to sprints exceeding 85% and 95% of their individual maximal speed (i.e., peak speed), which would create a protective effect for competing more safely13,14. These relative intensities require a reference value (i.e., peak speed), which can be used to determine the peak speed of each player. In this regard, practitioners can select speeds achieved during sprint tests or during competition, using global navigation satellite systems15. Considering that speeds achieved during field tests are generally higher than during training and matches15,16, retrieving peak speeds from real match scenarios could potentially represent a more realistic value. Moreover, during matches, players do not achieve their peak speeds with a linear acceleration, but rather through acceleration from running speeds approximately 4 s before the peak effort17. Thus, practitioners should plan specific drills to better prepare their players.

Beyond the association with maximum speed and injury prevention, it is also necessary to use sprint training to enhance players’ capabilities. Indeed, several proposals for sprint drills have been discussed in the literature. For example 3–4 repetitions of 40 m sprints with 6 min of recovery between repetitions18, while some authors have shown that sub-maximal sprint exercises may provide significant improvements over maximal sprinting performance19,20 without the need to impose maximal intensity stimuli, thus avoiding excessive stress on the neuromuscular system. Furthermore, recreationally active adults were expected to have a 30 m distance to build up speed (flying sprints), avoiding the need for the execution of higher intensity accelerations to attain maximum speed values18,19. However, although maximal speed capacity seems to be less resistant to adaptation compared to accelerated sprinting capacity19, there is a need to cover longer distances in order to improve it. In fact, high-level female American Football players attained higher mean speeds during the final 15 m of a 35 m sprint when sprints were preceded by flying starts21. Therefore, the use of flying sprints may be considered a useful method for attaining almost or even maximal sprinting intensities with a reduced cost of the acceleration component, thus inducing less fatigue.

Although a diversity of exercises can be applied to expose players to displacements exceeding their 85% and 95% individual peak speed, practitioners need to assess if players are indeed achieving those values, and how they are achieving them. Allowing players to have a build-up run before attaining higher speeds might impose less fatigue, allowing for a quicker recovery between sessions, which may facilitate training load and fatigue management during the training cycles. Furthermore, in order to achieve maximal or near-maximal speed intensities from stationary starts, it seems that players need to cover 40 m linearly15,22, depending on the individual capacity of each player since faster players might need longer distances. However, in football matches, rather than stationary, players often start sprinting maneuvers with an associated initial speed. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to compare peak speed dynamics – with a 20-second analysis – of different speed drills. We hypothesize that 40 m sprints, performed as linear runs starting either from a stationary position or executed as a bounding run will achieve higher intensity and consequently accumulate more distance within the upper thresholds of sprinting than the other drills.

Methods

Participants

Forty elite youth football players (age: 19.1 ± 1.4 years, weight: 73.1 ± 6.9 kg, height: 179.8 ± 7.3 cm) from two teams competing in the under-19 and under-23 Portuguese National Championship (highest national division for the specific age group) were invited to participate in this study. We have classified players as elite because 22 of them played in the Youth Champions League (Tier 4, according to McKay et al., 2022), while the remaining players could be classified as Tier 3 (national level)23. The maximum speed of the players was 32.6 ± 1.8 km/h, ranging between 30.6 and 34.8 km/h. All participants read and signed an informed consent form prior to participating in the study. The Ethical Committee at the University of Maia approved the study (#210/2024). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Protocol

The players participated in five different sessions, spaced one week apart, incorporating speed training into the competitive microcycle. The speed drills used for each data collection session followed a randomized order. All the tests were conducted during a competitive period with a microcycle of 7 days, following the same periodization program (tactical periodization). Each session began with a standard warm-up (mobility of the lower limb muscles, running technique exercises, and 2 submaximal 10 m sprints) designed for speed-focused days (e.g., Match Day − 2 (MD-2)), provided by a strength and conditioning coach, which was consistent across all sessions. The speed drills on MD-2 were compared across different conditions, such as stationary start linear sprints of 30 m (LS30) and 40 m (LS40), 15 m of bounding run + linear sprints of 30 m (15BR + 30) and 40 m (15BR + 40), and chasing sprints of 30 m (CS30). All drills were performed twice, and the best repetition was used for data analysis. Players were verbally motivated to reach their maximum speed in each condition under the following parameters: in the 15BR + LS30 and 15BR + LS40m exercises, players were required to increase their stride length only up to the 15 m marker cone, after which they were to reach their maximum speed. In the CS30m drill, players started 5 m behind the attacking player and attempted to intercept the attacker before they could shoot the ball, which had to occur within 30 m (before the penalty area). A more visually detailed description of the repetitions, feedback, and data selection for analysis for each drill can be seen in Fig. 1.

Diagram representation of all sprint drills and their respective feedback. LS30, linear sprint of 30 meters; LS40, linear sprint of 40 meters; 15BR+30, 15 meters of bounding run + linear sprint of 30 meters; 15BR+40, 15 meters of bounding run + linear sprint of 40 meters, and CS30, chasing sprints of 30 meters.

Procedures

External training load was monitored using a portable 10 Hz Global Positioning System (GPS) device (Catapult Vector S7, Catapult Sports, Melbourne, Australia), which has been certified by FIFA (certification number: 1003407) and validated for measuring ACC and DEC24, and maximal speeds25. To ensure higher data reliability, and reduce inter-unit error, each player consistently used the same GPS unit throughout all data collections. GPS data were downloaded using the manufacturer’s software (Catapult Openfield, version 3.10; Firmware 8.1). This study analyzed the peak speed over a 20-second window (Supplementary file 1), similarly to a previous study (for details, check Silva et al.17. Briefly, the peak speed was identified as the highest speed recorded, and data were collected within 201 data points, including speed and time from the preceding and subsequent 10 s of the peak speed. This data was used to construct the speed curve for each sprint drill. Specifically, the speed curve of each drill was constructed by averaging the players instantaneous speed. For example, the starting speed of drill A consists of the average speed registered in the first 0.1s from all players during that drill. Additionally, accelerations were calculated as the change in speed divided by the change in time, as long as speed continued to increase, without specifying a minimum effort duration26. The initial speed was defined as the average of the five lowest consecutive speed values within the 201 recorded data points. The speed recorded at 5 s before the peak speed and the closest acceleration before the peak speed (if magnitude was ≥ 1 m/s2, to avoid potential noise) were also retrieved for further analysis. To compare the external load of each sprint exercise, the distance covered at each threshold was calculated by normalizing it to each player’s maximal speed. The maximum speed used for threshold determination was obtained from the highest recorded value (to avoid outliers, the value considered must be recorded at least three times), either in training or competition, by the athletes throughout the season. High-speed running and sprinting were categorized with 3 levels of thresholds. The thresholds were defined as high-speed run 1 (HSR1) (55–65% of peak speed), HSR2 (> 65–75% of peak speed), HSR3 (> 75–85% of peak speed), Sprint1 (> 85–90% of peak speed), Sprint2 (> 90–95% of peak speed), and Sprint3 (> 95–100% of peak speed).

Statistical analysis

Raw data were organized and treated in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation; Version 16.89.1), and statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS statistical software (version 29, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). A mixed-model analysis was conducted to assess the differences in distance covered across exercise drills. Acceleration and distance covered in each speed zone were used as dependent variables, with exercise drill included as the fixed effect, and ID as a random effect. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Fisher’s least significant difference adjustment, and the significance level was established at p < 0.05. Cohen’s (d) effect sizes were calculated for each comparison and categorized as trivial (≤ 0.2), small (> 0.2–0.6), moderate (> 0.6–1.2), large (> 1.2-2.0), very large (> 2.0–4.0) and extremely large (> 4.0)27.

Results

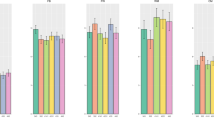

The descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1 and the time curves in relation to the percentage of maximum speed can be observed for each exercise drill in Fig. 2. An effect for condition (i.e., exercise drill) was observed for acceleration (F = 3.952; p = 0.004). Specifically, higher values were observed in LS30 (6.98 ± 1.43 m/s2) compared to 15BR + 30LS (5.62 ± 0.83 m/s2; p = 0.007; d = 1.16); LS40 (6.76 ± 1.60 m/s2) compared to 15BR + 30LS (5.62 ± 0.83 m/s2; p = 0.024; d = 0.9); and CS30 (7.09 ± 1.25 m/s2) compared to 15BR + 30LS (5.62 ± 0.83 m/s2; p = 0.009; d = 1.39).

For HSR1, an effect of condition was observed (F = 2.785; p = 0.027). Significantly larger distances were covered in 15BR + 30LS (6.46 ± 1.92 m) compared to LS30 (4.92 ± 2.43 m; p = 0.013; d = 0.7); 15BR + 30LS compared to LS40 (4.80 ± 3.0 m; p = 0.002; d = 0.64); and 15BR + 30LS compared to CS30 (4.68 ± 1.83 m; p = 0.011; d = 0.95).

In HSR2, HSR3, and Sprint1, no significant differences were observed between conditions (p = 0.203; p = 0.083; p = 0.091, respectively).

For Sprint2, a significant effect of condition was observed (F = 13.872; p < 0.001). Significantly larger distances covered were observed for LS40 (8.55 ± 7.31 m) compared to LS30 (3.40 ± 5.32 m; p < 0.001; d = 0.8); LS40 (8.55 ± 7.31 m) compared to 15BR + 40LS (3.90 ± 5.55 m; p < 0.001; d = 0.72); LS40 (8.55 ± 7.31 m) compared to 15BR + 30LS (1.90 ± 3.90 m; p < 0.001; d = 1.13); and LS40 (8.55 ± 7.31 m) compared to CS30 (0.91 ± 3.30 m; p < 0.001; d = 0.83).

For Sprint3, a significant effect of condition was also observed (F = 3.696; p = 0.006). Specifically, significantly larger distances were covered in LS40 (2.42 ± 4.82 m) compared to LS30 (0.90 ± 3.31 m; p = 0.01; d = 0.37), LS40 (2.42 ± 4.82 m) compared to 15BR + 40LS (0.97 ± 3.49 m; p = 0.024; d = 0.34), and LS40 (2.42 ± 4.82 m) compared to 15BR + 30LS (0.0 ± 0.0 m; p = 0.013).

Graphical representation of the 10 seconds preceding and succeeding the highest recorded speed during each drill. Black lines are mean and grey area standard deviation. A- Linear Sprint 30m; B- Linear Sprint 40m; C- 15m Bounding Run+ Linear Sprint 30m; D-5m Bounding Run+ Linear Sprint 40m; E - Chasing Sprint 30m; HSR1 - High speed running 1 (between 55% and 65 % of maximal speed); HSR2 - high speed running 2 (between 65% and 75%); HSR3 - high speed running 3 (between 75% and 85%). S1 - sprint 1 (between 85% and 90%); S2 - Sprint 2 (between 90% and 95%); and S3 - Sprint 3 (above 95%).

Discussion

This study examined different sprint drills in relation to the distances covered at various percentages of maximum speed, assessed using GPS data, among under-19 and under-23 Portuguese National Championship football players. The main findings were: (i) 15BR + 30LS (Fig. 2C) drill differed from all other conditions in HSR1 (between 55 and 65% of maximum speed), achieving higher values in this metric; (ii) 15BR + 30LS (Fig. 2C) drill was different from all other sprint drills, recording the lowest ACC value; (iii) LS40 (Fig. 2-B) drill showed significant differences in Sprint3 (> 95% of maximum speed) compared to all other sprint drills. These results provide valuable insights for coaches and practitioners aiming to optimize sprint training in football, as different drills elicit distinct speed and acceleration profiles. The LS40 (Fig. 2-B) and CS30 drills (Fig. 2-E) were found to be the most effective for achieving higher sprint and acceleration intensity, respectively.

Sprinting in football is a highly relevant high-intensity movement, as it is related to decisive actions during the game28,29, players often initiate those movements with some initial speed, rather than starting from a stationary position30. Therefore, flying sprints seem to be more specific to match-related demands. In this scenario, drills incorporating bounding runs as a form of flying start may be more representative of the game profile. Moreover, it was also expected that a higher initial speed would position the players closer to their peak speed, thereby favoring a greater accumulation of distance under very high-speed conditions. However, the present results indicate that they are not effective (especially 15BR + 30LS, Fig. 2-C) in providing sprint speed stimulus above 95% of peak speed (Sprint3 threshold) and higher maximal accelerations values. Therefore, our findings suggest that the constraints imposed by the tasks (initiating with a bounding run) may alter the mechanical pattern of running compared to a stationary start, allowing the player to accumulate greater distances in HSR zones when compared to sprinting. Regarding the acceleration, the lower values could be probably related to the high initial speed value before the linear sprint action19 reducing the ability to accelerate at higher speeds30,31. Furthermore, there is an inverse relationship between running speed and foot contact times32,33,34. The decreased contact time at higher speeds limits the impulse generated by the lower limb. Conversely, when accelerating from a stationary position, the longer time available for applying force results in greater acceleration values. This rationale is supported by a significant, near-perfect correlation (r= -0.98) between maximal voluntary acceleration and initial running speed35. However, as a consequence of higher intensities required to achieve peak speed from a stationary start, significant levels of fatigue may interfere with the microcycle organization, which must ensure the highest readiness level on game day. Therefore, research has shown that flying sprints are a superior method to achieve higher sprint speeds when compared to a stationary start36, as they remove the vigorous acceleration component of the latter, which is believed to have a significant energetic cost associated with it19,37. Consequently, this method could be used as an approach to minimize fatigue accumulation without compromising important muscular and performance adaptations. However, to attain peak speeds using this method, prolonging the sprinting distance could be necessary, leading to an increased external load at high speeds.

Despite the observed differences between the drills, all conditions enabled the athletes to reach the Sprint2 intensity (90–95% maximal speed), which was previously found to be related to increased myoelectric activity of the hamstrings during the swing phase of running, in track-and-field athletes38,39. When considering the results of this study, one can expect all drills to be effective in adequately stimulating the hamstrings complex since the athletes reached at least 95% of their maximum capacity. It is believed that sprinting at proper intensities likely induces tissue healing and repair, which may aid athletes during their rehabilitation process40, and should be considered as an important criterion for defining an adequate dosage of a “vaccine” aimed at preventing hamstring injuries. Although musculoskeletal injuries have a multifactorial profile, it has been suggested that this level of intensity has possibly been linked elsewhere to a lower risk of lower limb injury. Consequently, this approach to exercise prescription may prevent athletes from being exposed to sufficient sprint intensities, and the relationship between the risk of injury and the exposure to other types of sprints intensities should be addressed in future studies. Therefore, these findings highlight the need for further investigation.

Considering the present results and data from previous studies, if we aim to expose players to the highest intensity, we should provide at least 40-m linear distances when starting from a stationary position, and more than 40-m if preceded by a rolling start. It would be interesting to assess exactly what distance should be provided to the athletes when they perform flying sprints and if reducing the flying sprint distance might allow for higher early acceleration capacity, thereby enabling them to achieve the Sprint3 zone earlier. However, if acceleration is the focus of development, we advocate the use of CS30 (Fig. 2-E), as it presents the highest acceleration value of all drills. A plausible explanation is the visual feedback that the player receives, knowing they are positioned 5 m behind the player they are attempting to dispossess. This anticipatory response may elicit a more pronounced acceleration, as the athlete must quickly close the distance to execute the defensive maneuver effectively. The spatial and temporal constraints inherent in this drill likely contribute to the heightened acceleration values recorded.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it is possible to verify that before the first 10 s of the run, the athletes do not start from a completely stationary position. This is likely due to the GPS device being positioned on the torso, making it challenging to avoid detecting such variations, especially during the athlete’s initial movement when leaning forward before starting. Moreover, the limitations of GPS in identifying initial speed and acceleration must be taken into account, as the data is processed as a single instantaneous speed every 0.1 s, which increases the complexity of accurately identifying the moment of ‘cut-off’. However, the study’s goal is not to analyze absolute values, but rather to evaluate the curve of each sprint drill and compare the different exercise intensities. Therefore, this analysis takes into account and eliminates this potential effect. Secondly, it is only performed with linear sprints, and therefore the present results cannot be transferred to non-linear sprints. Thirdly, it should be considered that in the 15 m bounding drills, different stride patterns may lead to varying starting speeds after the 15 m mark. However, feedback was given to the players to achieve the longest possible stride up to the 15 m cone, and restricting the stride in the first 15 m would alter the running technique of the players, as the goal of the study was not to compare players but to analyze the drills. Finally, we cannot rule out a possible effect of accumulated fatigue due to games and training sessions, although the test sessions were randomized, standardized for the same day of the week, and conducted at the beginning of the training session with the drill.

Conclusion

This study clearly demonstrates the utility of using LS40m and CS30m to expose athletes to the highest speed and acceleration intensities. Furthermore, the flying start drills are effective in stimulating speeds between 85 and 95% peak speed which may be considered sufficient to properly stimulate the hamstrings at a neuromuscular and mechanical level. It would be interesting, in future investigations, to increase the distance covered in the flying sprint drills or to reduce the flying start speed, as it seems that players need more distance to achieve peak speed when starting at speeds of 55% maximum speed, which causes a decrease in the acceleration rate capacity. Overall, these findings offer valuable guidance for optimizing sprint training protocols and lay the groundwork for future research on enhancing speed and acceleration development in soccer players.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dalen, T., Ingebrigtsen, J., Ettema, G., Hjelde, G. H. & Wisløff, U. Player load, acceleration, and deceleration during Forty-Five competitive matches of elite soccer. J. Strength. Cond Res. 30, 351–359 (2016).

Martín-García, A., Gómez Díaz, A., Bradley, P. S., Morera, F. & Casamichana, D. Quantification of a professional football team’s external load using a microcycle structure. J. Strength. Cond Res. 32, 3511–3518 (2018).

Silva, H., Nakamura, F. Y., Castellano, J. & Marcelino, R. Training load within a soccer microcycle week—A systematic review. Strength. Cond J. 45, 568–577 (2023).

Borresen, J. & Lambert, M. I. The quantification of training load, the training response and the effect on performance. Sports Med. 39, 779–795 (2009).

Drew, M. K. & Finch, C. F. The relationship between training load and injury, illness and soreness: A systematic and literature review. Sports Med. 46, 861–883 (2016).

Banister, E. W. Modeling elite athletic performance. Physiological testing of the High–Performance. in Physiological Testing of the High-Performance Athlete (eds MacDougall, D., Wenger, H. A. & Green, H. J.) (Human Kinetics Books, Champaign, Illinois, (1991).

Chiu, L. Z. F. & Barnes, J. L. The Fitness-Fatigue model revisited: implications for planning Short- and Long-Term training. Strength. Cond J. 25, 42–51 (2003).

Diemer, W. M., Winters, M., Tol, J. L., Pas, H. I. M. F. L. & Moen, M. H. Incidence of acute hamstring injuries in Soccer: A systematic review of 13 studies involving more than 3800 athletes with 2 million sport exposure hours. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 51, 27–36 (2021).

Ekstrand, J. et al. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in Men’s professional football: the UEFA elite club injury study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. Br. J. Sports Med. 57, 292–298 (2022).

Small, K., McNaughton, L. R., Greig, M., Lohkamp, M. & Lovell, R. Soccer fatigue, sprinting and hamstring injury risk. Int. J. Sports Med. 30, 573–578 (2009).

Kalema, R. N., Duhig, S. J., Williams, M. D., Donaldson, A. & Shield, A. J. Sprinting technique and hamstring strain injuries: A concept mapping study. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 25, 209–215 (2022).

Gómez-Piqueras, P. & Alcaraz, P. E. If you want to prevent hamstring injuries in soccer, run fast: A narrative review about practical considerations of sprint training. Sports (Basel) 12, (2024).

Malone, S., Roe, M., Doran, D. A., Gabbett, T. J. & Collins, K. High chronic training loads and exposure to bouts of maximal velocity running reduce injury risk in elite Gaelic football. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 20, 250–254 (2017).

Campos Vázquez, M. Á., Zubillaga, A., Toscano Bendala, F. J., Owen, A. L. & Castillo-Rodríguez, A. Quantification of high speed actions across a competitive microcycle in professional soccer. J Hum. Sport Exerc 18, (2021).

Kyprianou, E. et al. To measure peak velocity in soccer, let the players sprint. J. Strength. Cond Res. 36, 273–276 (2022).

Al Haddad, H., Simpson, B. M., Buchheit, M., Di Salvo, V. & Mendez-Villanueva, A. Peak match speed and maximal sprinting speed in young soccer players: effect of age and playing position. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 10, 888–896 (2015).

Silva, H. et al. Peak match sprinting speed during soccer matches: analysing the pre- and post-peak speed dynamics. Biol. Sport. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2024.136089 (2025).

Haugen, T. A., Tønnessen, E. & Seiler, S. K. The difference is in the start: impact of timing and start procedure on sprint running performance. J. Strength. Cond Res. 26, 473–479 (2012).

Skoglund, A., Strand, M. F. & Haugen, T. A. The effect of flying sprints at 90–95% of maximal velocity on sprint performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 18, 248–254 (2023).

Haugen, T., Tonnessen, E., Leirstein, S., Hem, E. & Seiler, S. Not quite so fast: effect of training at 90% sprint speed on maximal and repeated-sprint ability in soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 32, 1979–1986 (2014).

Vescovi, J. D. Sprint speed characteristics of high-level American female soccer players: female athletes in motion (FAiM) study. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 15, 474–478 (2012).

Clemente, F. M. et al. Testing the peak running speed in analytical and contextual-based scenarios: applied research in young adult soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 41, 1372–1382 (2023).

McKay, A. K. A. et al. Defining training and performance caliber: A participant classification framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 17, 317–331 (2022).

Crang, Z. L. et al. The validity of Raw custom-processed global navigation satellite systems data during straight-line sprinting across multiple days. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 27, 204–210 (2024).

Cormier, P. et al. Concurrent validity and reliability of different technologies for Sprint-Derived horizontal Force-Velocity-Power profiling. J. Strength. Cond Res. 37, 1298–1305 (2023).

Silva, H. et al. Using minimum effort duration can compromise the analysis of acceleration and deceleration demands in football. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 23, 125–137 (2023).

Hopkins, W. G., Marshall, S. W., Batterham, A. M. & Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 3–13 (2009).

Faude, O., Koch, T. & Meyer, T. Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football. J. Sports Sci. 30, 625–631 (2012).

Martínez-Hernández, D., Quinn, M. & Jones, P. Linear advancing actions followed by deceleration and turn are the most common movements preceding goals in male professional soccer. Sci. Med. Footb. 7, 25–33 (2023).

Di Salvo, V., Gregson, W., Atkinson, G., Tordoff, P. & Drust, B. Analysis of high intensity activity in premier league soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 30, 205–212 (2009).

Haugen, T., Seiler, S., Sandbakk, Ø. & Tønnessen, E. The training and development of elite sprint performance: an integration of scientific and best practice literature. Sports Med. Open. 5, 44 (2019).

Murphy, A. J., Lockie, R. G. & Coutts, A. J. Kinematic determinants of early acceleration in field sport athletes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2, 144–150 (2003).

Hunter, J. P., Marshall, R. N. & McNair, P. Reliability of Biomechanical variables of sprint running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 36, 850–861 (2004).

Mann, R. & Herman, J. Kinematic analysis of olympic sprint performance: Men’s 200 meters. Int. J. Sport Biomech. 1, 151–162 (1985).

Sonderegger, K., Tschopp, M. & Taube, W. The challenge of evaluating the intensity of short actions in Soccer: A new methodological approach using percentage acceleration. PLoS One. 11, e0166534 (2016).

Young, W. B. et al. Gradual vs. maximal acceleration: their influence on the prescription of maximal speed sprinting in team sport athletes. Sports (Basel) 6, (2018).

Jeffreys, I. & Goodwin, J. E. Developing speed and agility for sports performance. in Strength and Conditioning for Sports Performance (eds. Jeffreys, I. & Moody, J.) 31Routledge, London, England, (2016).

Higashihara, A., Ono, T., Kubota, J., Okuwaki, T. & Fukubayashi, T. Functional differences in the activity of the hamstring muscles with increasing running speed. J. Sports Sci. 28, 1085–1092 (2010).

Willer, J., Allen, S. J., Burden, R. J. & Folland, J. P. How humans run faster: the neuromechanical contributions of functional muscle groups to running at different speeds. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 34, e14690 (2024).

Mendiguchia, J. et al. A multifactorial, Criteria-based progressive algorithm for hamstring injury treatment. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49, 1482–1492 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to football players who participated in the study.

Funding

This work was funded by National Funds by FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology under the following project UID/04045: Research Center in Sports Sciences, Health Sciences, and Human Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P. realized the conception of the study and its design. R.P., F.M., H.S. contributed to material preparation, and data processing and analysis. Data collection was performed by R.P. The first draft of the manuscript was written by R.P., and initially reviewed by H.S. and F.Y.N. commented on the previous version of the manuscript. R.P., F.M., H.S., and F.Y.N. read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pimenta, R., Maia, F., Silva, H. et al. The speed dynamics of different sprint and acceleration exercises applied during football training. Sci Rep 15, 29543 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04641-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04641-w