Abstract

Sleep is a fundamental physiological process essential for maintaining both physical and mental well-being. Various biological, environmental, and nutritional factors influence sleep quality, with recent studies focusing on the role of trace elements. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the individual and combined effects of serum levels of essential trace elements—specifically magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and selenium (Se)—on sleep quality among Iranian adults, utilizing the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). This cross-sectional study involved 99 individuals with sleep disorders who were referred to Farabi Hospital between October 2024 and February 2025. Sleep quality among participants was assessed using the PSQI, while serum levels of essential elements were analyzed through inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The study’s findings revealed a negative correlation between Fe concentration and total PSQI scores (Beta = − 0.02, 95% CI − 0.03 to 0.00, P = 0.03). Higher levels of Fe were associated with a reduced risk of poor subjective sleep quality (OR 0.984, 95% CI 0.971 to 0.995, P = 0.009) and shorter sleep latency (OR 0.986, 95% CI 0.972–0.990, P = 0.03). Additionally, an increase in Fe concentration correlated with improved habitual sleep efficiency (OR 0.984, 95% CI 0.968 to 0.997, P = 0.02). Using the quantile g-computation model, Fe was identified as the most significant factor influencing the overall PSQI score. Furthermore, the generalized additive model indicated notable non-linear relationships between Co and the global PSQI score (P = 0.02), as well as between Zn and the global PSQI score (P = 0.034). In conclusion, the results highlights that individuals with low serum Fe levels face a considerably higher risk of poor sleep quality. Additionally, Co concentration was found to exert a significant negative effect on the global PSQI score, further pointing to the importance of trace elements in sleep health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep is a vital physiological function that plays a crucial role in maintaining both physical and mental health1. However, in our fast-paced society, increasing social pressures have contributed to a rise in sleep disorders, which have emerged as a significant public health concern1,2. Epidemiological evidence indicates that the prevalence of sleep disorders is approximately 56% in the United States and ranges between 23 and 36% in various European countries3. In Iran, a recent study highlighted that 44.1% of the population experienced sleep disorders in 20224. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has established guidelines that classify sleep disorders into seven major categories: insomnia disorders, parasomnias, central disorders of hypersomnolence, sleep-related breathing disorders, circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders, and other sleep disorders. Understanding these classifications is essential for addressing the increasing prevalence of sleep disorders and improving sleep health5.

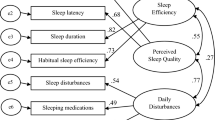

Poor sleep quality is a critical symptom of sleep disorders that significantly impacts overall health. This complex issue is evaluated using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) introduced by Buysse et al.6 and several key parameters, including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. Alarmingly, about 12% of adults in the U.S. report poor sleep quality7, with a study in Iran showing an even higher prevalence of 37%8. The consequences of inadequate sleep extend beyond fatigue; they are linked to serious physical health issues like cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, and neuropsychological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and depression9,10. Additionally, poor sleep increases the risk of unsafe behaviors and workplace accidents, with research indicating it can double the chances of injuries11. For example, the economic loss due to sleep disorders has been estimated at $41–62 billion in Germany, $14–22 billion in Canada, and $94–146 billion in Japan12. Therefore, given the high prevalence and adverse consequences of poor sleep quality, identifying risk factors associated with it seems essential. In general, many biological, environmental, and dietary factors influence sleep quality. One factor that has received attention in recent years is the concentration of various metals, including toxic and essential metals9,13,14. Among the aforementioned metals, essential trace metals hold particular significance due to their crucial roles in the physiological processes of the human body15. These functions encompass the modulation of cellular signaling, the metabolism of oxygen, the defense against oxidative stress, and the synthesis of neurotransmitters, while deficiencies in these metals may lead to compromised structural integrity and physiological functionality15.

Recent estimates reveal the profound economic impact of sleep disorders, with losses between $41 billion and $62 billion in Germany, $14 billion to $22 billion in Canada, and $94 billion to $146 billion in Japan12. Given the serious consequences of poor sleep quality, identifying contributing risk factors is crucial. Among various biological, environmental, and dietary influences, the concentration of essential trace metals has emerged as a key factor9,13,14. These metals play vital roles in cellular signaling, oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress defense, and neurotransmitter synthesis. Deficiencies in these essential metals can significantly impair our physiological functions. Addressing these deficiencies may be essential for improving sleep quality and enhancing public health and economic productivity15. Indeed, metals such as sodium (Na), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), cobalt (Co), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and molybdenum (Mo) are essential for life and the human body must receive adequate amounts of them16.

Limited evidence on the improvement of sleep quality with essential trace metal supplementation suggests that some of these metals may also affect sleep quality13. For example, iron has been shown to play a key role in the metabolism of monoamines in the brain, and these same monoamines also affect sleep17. One study showed that iron supplementation significantly improved sleep quality in iron-deficient individuals18. Changes in cobalt levels at various thresholds can affect sleep quality; higher concentrations of cobalt have been associated with negative impacts on sleep quality through their actions on neurological functions. Cobalt exposure is related to oxidative stress and neurodegeneration, particularly affecting the Purkinje cells in the cerebellum, which can disrupt normal regulation of sleep19,20,21. Conversely, although excessive amounts of cobalt are associated with compromised sleep quality, it should be noted that cobalt is an essential trace element for vitamin B12, and thus low levels may not necessarily cause harm21. The association is therefore complex, and thus proper monitoring of cobalt exposure is required to prevent possible health hazards. In addition, studies have shown that Mg supplementation can have a calming effect on the central nervous system, resulting in better sleep by reducing serum cortisol concentrations, a stress-related hormone2. Zn and Cu are other essential metals involved in many metabolic reactions. They also serve as antagonists to the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor within the central nervous system, which functions as a crucial mediator in the modulation of mood, cognitive processes, pain perception, and sleep regulation22. A cross-sectional study showed that serum and hair Zn and Cu levels in women may affect sleep duration22. Manganese (Mn) exposure is linked with sleep disruption primarily due to its neurotoxic effect on the central nervous system. Manganese toxicity can lead to neuropsychological effects like extreme sleep disruption, irritability, and emotional lability. Mn buildup in the basal ganglia disrupts normal neurological activity, causing psychiatric disturbances and sleep disorders23. This is a crucial oversight, as trace metals can have both synergistic and antagonistic effects on sleep, potentially leading to misleading conclusions15. Furthermore, most existing studies have primarily examined sleep duration1,2,14, with few exploring the relationships between essential trace metals and sleep quality or disorders, often yielding conflicting results15. This study aims to investigate the individual and combined effects of serum concentrations of essential trace metals—Mg, Ca, Fe, Mn, Co, Cu, Zn, and Se—on the PSQI component scores and related parameters.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The demographic characteristics of the 99 participants in this study are presented in Table 1. The average age of all participants was 46.04 years, with a standard deviation of 12.75 years. The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) was 28.77, with a standard deviation of 5.81. The majority of participants (57.6%) were male, and significant portions (83.8%) were married. Additionally, almost half of the participants (41.4%) had completed some form of higher education. Most participants were non-smokers (82.8%), and a large majority (88.9%) reported no involvement with opioids. Furthermore, over half of the participants (52.5%) had at least one underlying health condition. It is important to note that among the variables examined in Table 1, BMI, gender, and marital status showed significant associations with the PSQI component scores, with a p-value of less than 0.05. Participants reported an average consumption of four servings of tea daily, while only nine consumed coffee. Therefore, when fitting the regression models, the effect of these variables on the response was adjusted.

The mean global PSQI component scores for all participants were 11.04 ± 5.87, and the majority of participants (79.8%) had poor sleep quality (global PSQI component scores > 5). Table 2 summarizes information from the PSQI parameters. Based on the results in this table, 61.6% of participants had bad subjective sleep quality (score > 1). 42.4% of the participants had a sleep latency of more than 60 min. Almost half of the participants (47.5%) got less than 5 h of sleep per night. Only 11.2% of people had habitual sleep efficiency between 65 and 84%. Most participants (60.6%) had not used any sleep medications in the past month, and most (74.7%) also had daytime dysfunction. The distribution of essential metal concentrations is shown in Table 3. The GM values of essential metal concentrations, in order from highest to lowest, refer to Fe, Zn, Cu, Ca, Se, Mn, Co, and Mg with values of 176.63, 66.67, 59.36, 6.11, 5.81, 5.17, 1.31, and 0.82.

Multiple linear regression models

A multiple linear regression model was used to examine the impact of individual metals on the global PSQI component scores. This model accounted for variables such as BMI, gender, and marital status. According to the results presented in Table 4, the concentration of Co had a significant negative effect on the global PSQI component scores (Beta = − 0.78, 95% CI − 1.63, 0.07, P value = 0.04). This indicates that higher concentrations of Co led to a decrease in the global PSQI component scores. Similarly, Fe also demonstrated a negative association with the global PSQI component scores, with a coefficient of Beta = − 0.02 (95% CI − 0.03, 0.00, P value = 0.03). These regression coefficients reveal that increasing levels of both Co and Fe metals are linked to poorer sleep quality among the participants. It’s important to note that the effects of other elements on sleep quality were not confirmed in this study, as indicated in Table 4.

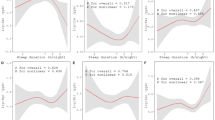

Quantile g-computation models

The results of fitting the quantile g-computation model are presented in the lower part of Table 4. According to the findings, a simultaneous one-quartile increase in the concentration of all eight essential metals resulted in a decrease in global PSQI component scores; however, this effect was not statistically significant (Beta = − 0.54, 95% CI − 2.97, 1.89, P value = 0.66). The individual metal weights estimated from the quantile g-computation model are illustrated in Fig. 1. The positive or negative weight assigned to each variable indicates its effect (either increasing or decreasing) on the global PSQI component scores. Among the metals analyzed, Fe emerged as the most significant factor, displaying the largest negative weight, which indicates it has the strongest negative impact on global PSQI component scores. Conversely, Se played a crucial role in contributing positively to the mixture’s effect on global PSQI component scores, having the highest positive weight. In comparison, Ca appears to have a minimal contribution to the response relative to the other metals.

Multiple logistic regression models

A multiple logistic regression model was used to examine the individual effect of essential metal concentrations on the PSQI parameters (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, daytime dysfunction) (Table 5). Note that each of the models was adjusted for the variables BMI, gender and marital status. Increasing Se metal concentration was associated with an increased the risk of poor subjective sleep quality (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.05, 1.50, P value = 0.01; Table 5). However, increasing Fe concentration was associated with a decreased the risk of poor subjective sleep quality (OR 0.984, 95% CI 0.971, 0.995, P value = 0.009) and decreased the risk of sleep latency (OR 0.986, 95% CI 0.972, 0.99, P value = 0.03). Increased Fe concentration was also was associated with a decreased in habitual sleep efficiency score, or in other words, an increase in sleep efficiency (OR 0.984, 95% CI 0.968, 0.997, P value = 0.02). Cu metal exposure associated with an increased the risk of shortened sleep duration (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00, 1.04, P value = 0.04). Mn metal exposure was associated with an increased risk of sleep disturbances (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.08, 1.52, P value = 0.006).

Generalized additive models (GAMs)

The non-linear effects of metal concentration on the global PSQI parameters were investigated using GAMs. The results of fitting this model are shown in Fig. 2. Based on the results, there was a significant non-linear relationship between Co and global PSQI parameters (P value = 0.02) as well as Zn and global PSQI parameters (P value = 0.034). A relatively non-linear relationship was also found between Se and global PSQI parameters, but this relationship was not significant (P value = 0.07).

Discussion

Our study reveals that individuals with low serum iron (Fe) levels have a significantly increased risk of poor sleep quality, reinforcing the vital link between Fe and sleep health across all age groups17,24,25,26,27,28,29. Fe is essential for oxygen transport and myelin sheath synthesis, and its deficiency is strongly associated with reduced sleep quality and higher rates of sleep disorders17,28,29. For example, research by Sincan et al.28 indicates that iron deficiency anemia negatively impacts both sleep quality and overall quality of life. Similarly, Murat et al. found that those with iron deficiency anemia experience worse sleep compared to healthier individuals17. A study in China further highlights this issue, showing that anemic patients are 1.32 times more likely to suffer from insomnia30. These findings emphasize the importance of maintaining adequate iron levels for optimal sleep health and overall well-being.

A cross-sectional study has identified a potential link between iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and increased nighttime awakenings and reduced total sleep duration in infants compared to those with adequate nutrition31. Supporting this, an observational study found that adults with lower iron intake are more likely to experience very short sleep (less than 5 h), even after adjusting for overall diet24. Furthermore, a longitudinal study revealed that children who had IDA in infancy displayed altered patterns of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep by age four, compared to non-IDA peers32. However, recent research reports no significant relationship between anemia status and sleep quality, which contrasts with earlier findings33. This discrepancy may arise from variations in assessment tools; the study used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), which encourages subjective responses and lacks specificity regarding sleep disorders. This underscores the need for more precise evaluation methods to better understand the connection between anemia and sleep quality. Other studies, however, quantified sleep quality through more specific tools, including the PSQI questionnaire or the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. PSQI is used to quantify sleep quality during the previous month. PSQI has been widely used and validated6. ROMIS, on the other hand, quantifies respondents’ sleep quality during the previous week. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why the study could not establish a significant correlation.

The relationship between the micronutrient status, in terms of Fe content in various biological samples, and sleep quality has been studied in numerous research studies. In a cohort study of 226 adolescents (106 females) in the Jintan Child Cohort, adolescents with lower Fe levels (< 75 μg/dl) (OR 1.29, P = 0.04) and lower Zn levels (< 70 μg/dl) (OR 1.58, P < 0.001) had higher odds of having poor sleep quality26. The results of a study showed a potential relationship between Fe, Se, Cu, Mn, folate, vitamin A, and vitamin E levels in the whole blood of older Chinese subjects and the risk of sleep disorder, as determined by employing a matched case–control study design27. Elevated serum Fe levels had a positive correlation with sleep latency (difficulty in sleep onset) (OR 0.68, P = 0.03) in adolescents aged 11–14 years in another research. There were no significant correlations between Fe and any of the sleep subdomains of PSQI instrument34. Likewise, urinary Fe levels were negatively correlated with global PSQI score, in a way that higher Fe exposure was associated with better quality of sleep during early pregnancy13. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that Fe supplementation can help to enhance sleep quality and decrease RLS symptoms in Fe-deficient patients18. One clinical trial demonstrated that the administration of Fe and Zn supplements separately led to longer nocturnal sleep duration in infants but that the group receiving Fe and Zn supplements combined did not experience the same benefits in sleep duration35. Trace elements interact with each other in complex ways, either synergistically or antagonistically, depending on physiological conditions and dietary intake. Zn and Cu are essential for Fe and Co metabolism, with complex interactions that can either support or hinder function. Zn helps regulate Fe metabolism and maintain balance, while Cu is crucial for Fe absorption and conversion36. However, high Zn intake can inhibit Fe absorption and lower Cu levels, leading to potential anemia37. Co also disrupts Zn and Cu balance, affecting essential enzymatic functions38. A balanced intake of these trace elements is vital for optimal health and Fe metabolism.

Despite the scarce information on the neurobiological pathways through which the primary effects of micronutrients on sleep are exerted, some causal pathways through which micronutrients affect sleep, as observed in experimental studies, have been hypothesized by researchers. For instance, micronutrients may play a key role in synthesizing and transporting neurotransmitters that are involved in the control of sleep homeostasis. In contrast to iron, zinc, copper, and magnesium, which have been implicated in blockers of excitatory signaling pathways, e.g., N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor and dopaminergic neurons, micronutrients may also regulate inhibitory signaling, e.g., gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptors34. The action of iron on the dopaminergic system is multifaceted. It is a cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, an important enzyme in the functioning of dopamine D2 receptors. The dopaminergic system plays a key role in neuromodulation during sleep regulation, encompassing modulation of the quality, quantity, and duration of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep17. The pathway by which iron deficiency worsens sleep quality may also be associated with RLS (Restless Leg Syndrome) formation. RLS is a sensory neurology disorder that is marked by an uncontrollable urge to move during rest and the sensation of leg discomfort like aching, burning, or creeping39. Iron deficiency affects brain dopamine levels and activation of D3 receptors and, therefore, contributes to RLS formation40. Moderate to severe RLS can cause nighttime restlessness and tends to shorten the sleep duration, causing disrupted and poor sleep quality41. The mechanisms underlying micronutrient involvement in sleep regulation also warrant the need for additional exploration of the impact of micronutrient status on sleep.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. Sleep quality was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire, specifically the PSQI parameters. While this instrument has excellent psychometric properties, it would be beneficial to validate the results further through studies that utilize sleep diaries. Although we adjusted for several confounding variables, there remains a possibility that unmeasured factors could still influence the results. Additionally, we lacked information on participants’ alcohol, dietary records, and substance uses, which could have impacted sleep outcomes. To enhance future research, it is essential to include more confounding variables related to alcohol and potential substance uses in the analyses. Finally, it is important to note that the observational design of this study limits our ability to draw causal conclusions from the findings.

Conclusion

This population-based study significantly enhances our understanding of the impact of micronutrients on sleep patterns. The findings reveal that Fe is the most influential metal regarding overall sleep quality, outpacing other essential nutrients. The Quantile g-computation model identifies higher Fe concentrations as linked to lower PSQI component scores, indicating better sleep quality. Additionally, increased Fe levels correlate with a reduced risk of poor subjective sleep quality and shorter sleep latency. In contrast, Co negatively affects the global PSQI component scores, demonstrating a weaker influence than Fe. The study also reveals complex, non-linear relationships between Zn and Co levels and sleep quality, highlighting the intricate interactions among these metals. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring Fe alongside other vital metals to enhance sleep health. Further research is crucial to replicate these relationships and uncover the underlying mechanisms.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted among patients experiencing sleep disorders (n = 99) who were referred to the Sleep Disorders Center at Farabi Hospital, affiliated with Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences from October 2024 to February 2025 (Fig. 3). All methods were performed in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Initially, a psychiatrist diagnosed the sleep disorders, and this diagnosis was subsequently verified using a polysomnography device. All subjects provided informed consent before participating in the study. Blood samples (3 cc) were collected from participants at the Sleep Disorders Center and processed through centrifugation to separate the serum. The study included participants of both sexes, aiming to investigate the relationship between serum levels of essential metals and sleep quality. To assess sleep quality, the PSQI questionnaire was utilized, which comprises seven scales: Subjective Sleep Quality, Sleep Latency, Sleep Duration, Sleep Efficiency, Sleep Disturbances, Use of Sleep Medications, and Daytime Dysfunction.

The inclusion criteria for the study focused on adult participants experiencing sleep problems, encompassing both males and females. In contrast, the exclusion criteria were quite specific, eliminating several groups from the study. Individuals who were shift workers or diagnosed with sleep disorders such as central sleep apnea, obstructive sleep apnea (if undergoing treatment), narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, chronic insomnia, or restless legs syndrome were excluded. Additionally, participants using complementary medications were not eligible. Other exclusion factors included those with respiratory diseases requiring medication, individuals with underlying health conditions such as congestive heart failure or cancer, and those suffering from acute infectious diseases, liver dysfunction, or abnormal kidney function. Pregnant or lactating women were also disqualified from participation (Fig. 3). Through these criteria, the study aimed to focus on a specific cohort with sleep complaints while minimizing confounding factors.

After enrollment in the study, each subject had 3 cc of blood collected. The blood was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm (corresponding to 1006.2 g-force) to separate the components. The resulting serum samples were carefully transferred to labeled microcentrifuge tubes and stored in a freezer at − 70 °C in preparation for the digestion stage. For the digestion process, 1 ml of serum was combined with 3 ml of 65% nitric acid (HNO3, 65%, Suprapore, Merck, Germany) and 1 ml of 70% perchloric acid (HClO4, 70%, Merck, Germany) in a digestion system (Bain-Marie—TW12, Julabo GmbH, Germany) set to 98 °C. After allowing the samples to cool in the laboratory environment, they were filtered through a cellulosic filter. Subsequently, the volume of the filtered samples was adjusted to 25 ml using deionized water (18.2 MΩ-cm at 25 °C, Fistreem, WSC044, UK). Following digestion, the levels of selected trace elements were measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) on a PerkinElmer-7300 DV instrument. Prior to measurement, the device was calibrated, and the recovery rate for each metal was determined. The recovery rates for all examined trace elements varied between 91 and 98%. The limits of detection (LOD) for essential elements are vital for precise analysis: iron at 0.02, cobalt at 0.02, calcium at 0.03, copper at 0.05, manganese at 0.08, magnesium at 0.05, selenium at 0.07, and zinc at 0.1 µg L−1. To ensure accuracy, five analyses were conducted for both spiked fractions and control samples, with adjustments made to align with the midpoint of the methods’ working range. Additionally, certified reference material (CRM) BCR-185R and spikes were utilized in the analysis. The essential metals analyzed included iron, copper, manganese, cobalt, and selenium, with a significance level set at 5%.

The demographic variables examined in this study were described using means and standard deviations or frequencies and percentages. Since the values related to the concentration of essential metals were skewed, the geometric means (GM) as well as the median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe these variables. Multiple linear regression was used to examine the effect of each essential metal concentration on the quantitative response variable (global PSQI component scores), adjusting for other variables. In addition, the PSQI parameters (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, daytime dysfunction) were converted into binary variables such that a score of ≥ 2 for each parameter was considered moderate to severe sleep difficulty13. After binarization, the effect of essential metal concentrations on these parameters was examined using logistic regression. The nonlinear effects of metals on the global PSQI parameters were also examined using a generalized additive model (GAM) and splines. To examine the overall effect of metal composition, quantile g-computation models were used, and in addition to the overall effects, the individual effects of metals and their corresponding weights were displayed. In this graph, the weights indicate the relative effect of each metal on the response, with positive weights indicating an increasing effect and negative weights indicating a decreasing effect of metals on the global PSQI parameters. In the present study, the Gaussian family was used to calculate the parameters and q was set to 4. In addition, all models were fitted after adjusting for variables that had a significant relationship with the response. It should be noted that the significance of all tests was considered at the 0.05 level, and all analyses were performed in the R software environment, version 4.0.3. The GAM model was fitted using the “gam” function in the “mgcv” package42, and the quantile g-computation model was fitted using the "qgcomp.noboot" function in the “qgcomp” package43.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Luo, Z., Zhu, N., Xiong, K., Qiu, F. & Cao, C. Analysis of the relationship between sleep-related disorders and cadmium in the US population. Front. Public Health 12, 1476383 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association of magnesium intake with sleep duration and sleep quality: findings from the CARDIA study. Sleep 45, zsab276 (2022).

Léger, D., Poursain, B., Neubauer, D. & Uchiyama, M. An international survey of sleeping problems in the general population. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 24, 307–317 (2008).

Khazaie, H. et al. The prevalence of sleep disorders in Iranian adults-an epidemiological study. BMC Public Health 24, 3141 (2024).

Sateia, M. J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: Highlights and modifications. Chest 146(5), 1387–1394 (2014).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. III., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatr. Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Khosravi, A., Emamian, M. H., Hashemi, H. & Fotouhi, A. Components of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Iranian adult population: An item response theory model. Sleep Med. X 3, 100038 (2021).

Asghari, A., Kamrava, S. K., Ghalehbaghi, B. & Nojomi, M. Subjective sleep quality in urban population. Arch. Iran. Med. 15, 95–98 (2012).

Kim, B. K., Kim, C. & Cho, J. Association between exposure to heavy metals in atmospheric particulate matter and sleep quality: A nationwide data linkage study. Environ. Res. 247, 118217 (2024).

Itani, O. et al. Sleep-related factors associated with industrial accidents among factory workers and sleep hygiene education intervention. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 16, 239–251 (2018).

Mohammadyan, M., Moosazadeh, M., Borji, A., Khanjani, N. & Rahimi Moghadam, S. Exposure to lead and its effect on sleep quality and digestive problems in soldering workers. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 1–9 (2019).

Mendonça, F., Mostafa, S. S., Morgado-Dias, F., Ravelo-Garcia, A. G. & Penzel, T. A review of approaches for sleep quality analysis. IEEE Access 7, 24527–24546 (2019).

Song, J. et al. Exposure to a mixture of metal (loid) s and sleep quality in pregnant women during early pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 281, 116663 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. The association of mixed multi-metal exposure with sleep duration and self-reported sleep disorder: A subgroup analysis from the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES). Environ. Pollut. 361, 124798 (2024).

Deng, M.-G. et al. Associations of serum zinc, copper, and selenium with sleep disorders in the American adults: Data from NHANES 2011–2016. J. Affect. Disord. 323, 378–385 (2023).

Zoroddu, M. A. et al. The essential metals for humans: A brief overview. J. Inorg. Biochem. 195, 120–129 (2019).

Semiz, M. et al. Assessment of subjective sleep quality in iron deficiency anaemia. Afr. Health Sci. 15, 621–627 (2015).

Macher, S. et al. The effect of parenteral or oral iron supplementation on fatigue, sleep, quality of life and restless legs syndrome in iron-deficient blood donors: A secondary analysis of the IronWoMan RCT. Nutrients 12, 1313 (2020).

Akinrinde, A., Adigun, K. & Mustapha, O. Cobalt-induced neuro-behavioural alterations are accompanied by profound Purkinje cell and gut-associated responses in rats. Environ. Anal. Health Toxicol. 38, e2023010 (2023).

Obied, B. et al. Structure-function correlation in cobalt-induced brain toxicity. Cells 13, 1765 (2024).

Uddin, M. H. & Rumman, M. Metal Toxicology Handbook 273–285 (CRC Press, 2020).

Song, C.-H., Kim, Y.-H. & Jung, K.-I. Associations of zinc and copper levels in serum and hair with sleep duration in adult women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 149, 16–21 (2012).

Inoue, N. Occupational neurotoxicology due to heavy metals-especially manganese poisoning. Brain Nerve = Shinkei kenkyu shinpo 59, 581–589 (2007).

Grandner, M. A., Jackson, N., Gerstner, J. R. & Knutson, K. L. Dietary nutrients associated with short and long sleep duration. Data from a nationally representative sample. Appetite 64, 71–80 (2013).

Peirano, P., Algarín, C., Garrido, M., Algarín, D. & Lozoff, B. Iron-deficiency anemia is associated with altered characteristics of sleep spindles in NREM sleep in infancy. Neurochem. Res. 32, 1665–1672 (2007).

Ji, X. et al. Serum micronutrient status, sleep quality and neurobehavioural function among early adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 24, 5815–5825 (2021).

Cheng, C. et al. A risk correlative model for sleep disorders in chinese older adults based on blood micronutrient levels: A matched case-control study. Nutrients 16, 3306 (2024).

Sincan, G., Sincan, S. & Bayrak, M. The effects of iron deficiency anemia on sleep and life qualities. (2022).

Leung, W., Singh, I., McWilliams, S., Stockler, S. & Ipsiroglu, O. S. Iron deficiency and sleep–A scoping review. Sleep Med. Rev. 51, 101274 (2020).

Neumann, S. N. et al. Anemia and insomnia: A cross-sectional study and meta-analysis. Chin. Med. J. 134, 675–681 (2021).

Kordas, K. et al. Maternal reports of sleep in 6–18 month-old infants from Nepal and Zanzibar: Association with iron deficiency anemia and stunting. Early Human Dev. 84, 389–398 (2008).

Peirano, P. D., Algarín, C. R., Garrido, M. I. & Lozoff, B. Iron deficiency anemia in infancy is associated with altered temporal organization of sleep states in childhood. Pediatr. Res. 62, 715–719 (2007).

Helmyati, S., Fauziah, L. A., Kadibyan, P., Sitorus, N. L. & Dilantika, C. Relationship between anemia status, sleep quality, and cognitive ability among young women aged 15–24 years in Indonesia (Analysis of Indonesian family life survey (IFLS) 5). Amerta Nutr. 7, 1–9 (2023).

Ji, X. & Liu, J. Associations between blood zinc concentrations and sleep quality in childhood: A cohort study. Nutrients 7, 5684–5696 (2015).

Kordas, K. et al. The effects of iron and/or zinc supplementation on maternal reports of sleep in infants from Nepal and Zanzibar. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 30, 131–139 (2009).

Scheers, N. Regulatory Effects of Cu, Zn, and Ca on Fe absorption: The intricate play between nutrient transporters. Nutrients 5, 957–970 (2013).

Bremner, I. & Beattie, J. H. Copper and zinc metabolism in health and disease: Speciation and interactions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 54(2), 489–499 (1995).

Gholizadeh, A. & Hosseini, S. Zn/Co co-substitution: Tuning the physical properties of CuFe2O4 nanoparticles. J. Sol-Gel. Sci. Technol. 17, 1–2 (2025).

Leschziner, G. & Gringras, P. Restless legs syndrome. BMJ 344, e3056 (2012).

Ghahremanfard, F., Semnani, M. R., Mirmohammadkhani, M., Mansori, K. & Pahlevan, D. The relationship between iron deficiency anemia with restless leg syndrome and sleep quality in workers working in a textile factory in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Middle East Curr. Psychiatr. 30, 23 (2023).

Allen, R. P., Auerbach, S., Bahrain, H., Auerbach, M. & Earley, C. J. The prevalence and impact of restless legs syndrome on patients with iron deficiency anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 88, 261–264 (2013).

Wood, S. & Wood, M. S. Package ‘mgcv’. R Package Version 1, 729 (2015).

Keil, A. P. et al. A quantile-based g-computation approach to addressing the effects of exposure mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 128, 047004 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for their financial support. The authors of this research are grateful for the valuable comments of Dr. Ali Zakei and Dr. Mohammad Taher Moradi. Additionally, we extend our sincere appreciation to all participants of this project. We also extend our thanks to the Clinical Research Development Center of Imam Khomeini and Mohammad Kermanshahi and Farabi Hospitals affiliated to Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for their kind support.

Funding

This study was conducted with a financial support received from the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 50005261).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BM, NE, and ZR generated the idea and design of the study. SK, SN, BM, HK, and MB searched the literature in databases, and wrote parts of the manuscript. ZM and HK participated in statistical analyses and edited the result part. ZM, SN, AE, OD, ZR, reviewed the manuscript. SN, OD, and BM wrote the discussion section, and with BM supervised all parts of the revision part of the manuscript. BM served as the corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study’s protocols were reviewed and approved by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences’ Ethics Committee (Ethics code: IR.KUMS.REC.1404.040). Also, each participating woman reviewed the study protocol and signed a consent form prior to being enrolled in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kakaei, S., Hassan, N.E., Nakhaee, S. et al. Associations between essential trace elements and sleep quality in Iranian adults based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sci Rep 15, 19713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04654-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04654-5