Abstract

The main objective of this research is to get a comprehensive view on the subsurface geological data on the Esh El Mellaha area and environs, Red Sea, Egypt. This includes determining the depth and structural characteristics of the basement surface beneath the region, as well as identifying additional gravity and magnetic sources and potential structures within the sedimentary cover. To achieve this goal, Bouguer gravity and aeromagnetic data were used, processed and analyzed. Various depth estimation techniques were employed to analyze subsurface structures, each offering distinct advantages. Euler Deconvolution effectively delineates structural discontinuities and fault systems, while the Source Parameter Imaging (SPI) method improves depth accuracy through wavenumber analysis. The Analytical Signal method enhances resolution, providing detailed depth variations. Across these methods, the estimated depth ranges from 300 to 5000 m, with an average depth of approximately 2380 m, offering critical insights into the subsurface geological framework. Two-dimensional (2.5D) modeling was conducted on two selected gravity and magnetic profiles to estimate the depth, dip, density, and magnetic susceptibility of the source bodies. Additionally, three-dimensional (3D) modeling was applied to Bouguer gravity and Reduced-to-the-Pole (RTP) magnetic profiles, providing a detailed representation of the causative source structures. The results of the 3D inversion of gravity and magnetic data reveal the subsurface distribution of density and magnetic susceptibility, aiding in the identification of major geological structures. The sectional maps and 3D models illustrate the vertical and horizontal variations in subsurface formations, highlighting distinct anomaly zones that may correspond to faults and lithological changes. The obtained results indicate that the sedimentary succession thickness is ranging from 1.0 to 2.2 km, a finding corroborated by the borehole data. Positive structural features identified in these models suggest promising targets for potential hydrocarbon reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Gulf of Suez basin hosts over 80 oil-producing fields, spanning reservoirs from the Precambrian to the Tertiary periods. This prolific region has attracted extensive geological research, driven by the abundance of exploration data and the exceptional exposure of syn-rift strata. These studies have significantly contributed to our understanding on the rift evolution and tectonic development of the basin. Recent works1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 have explored the structural, stratigraphic and depositional aspects of the Gulf of Suez. Additionally, contributions by Sarhan and Basal11 and Shehata et al.12 have further elucidated the dynamics of this complex rift system, highlighting its significance in petroleum exploration and basin analysis.

The study area is located in the northeastern part of the Egyptian Eastern Desert, southwest of the Gulf of Suez, between latitudes 27°25′ 00″ N and 27°46′ 00″ N, and longitudes 33°08′ 00″ E and 33°36′ 00″ E (Fig. 1A). It marks the northern extension of the western section of the Arabian-Nubian Shield (ANS), a region that has been significantly influenced by tectonic and thermal events associated with the Pan-African Orogeny (PAO) during the Neoproterozoic period, roughly 950 to 545 million years ago13,14,15,16,17.The basement rocks in the study area are structurally linked to the Pan-African Orogeny, which extends across the entire ANS in Egypt, Sudan, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

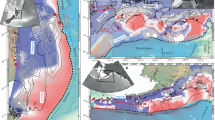

(A) A political map of Egypt illustrating the study area, marked by a rectangular orange box, within the Gulf of Suez region modified from Google Earth Image using CorelDraw Softwere50 (B) A tectonic map showing major fault trends and accommodation zones, such as the Zaafarana (ZAZ) and Morgan (MAZ) zones, adapted from previous studies4,47,48. (C) A surface structural map of the study area traced from Conoco Coral map gifted from General Petroleum Corporation of Egypt to Geology Department, Faculty of Science, Sohag University, Egypt , and (D) A simplified geologic map, modified from Masoud and CONOCO using the same Software as in (A)24,50,51.

This study aims to investigate the structural and tectonic framework of the Esh El Mellaha area in the Red Sea Basin by leveraging potential field data, specifically gravity and magnetic datasets. The Red Sea Basin is characterized by its intricate rift system and complex geological history, making it a prime location for detailed geophysical analysis. The research focuses on deriving subsurface geological insights by achieving the following objectives: Determining the structural configuration: analyzing the structural layout of the basement complex surface to understand fault systems and tectonic patterns. Estimating the sedimentary cover thickness: Calculating the depth and distribution of the sedimentary layers beneath the study area to assess its potential for resource exploration. Identifying anomalous sources: locate additional gravity and magnetic sources responsible for the anomalies observed in the geophysical maps, such as intrusive bodies or structural highs. Inferring subsurface structures: interpreting potential tectonic and structural features within the sedimentary section that could influence resource accumulation and tectonic activity.

The aeromagnetic anomaly map is a powerful tool for understanding the geological framework of the study area. It helps delineate faults, basement structures and mineralized zones, as well as providing insights into tectonic evolution, basin development and magmatic processes. These interpretations are crucial for resource exploration (minerals, hydrocarbons), geological mapping, and understanding the region’s structural and tectonic history.

Applying geophysical modeling techniques makes it possible to have insights into the tectonic history and structural evolution of the area concerned, essential for both geological interpretation and exploration activities in the Red Sea region. This approach integrates Bouguer gravity and aeromagnetic data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the geological and tectonic setting of the region, contributing to exploration efforts and geological modeling.

The Neoproterozoic basement complex in the study area is traversed by various dyke swarms with varying orientations and densities. The dykes are most densely concentrated in the granodioritic rocks located in the northwestern portion of the area. Their orientations are closely aligned with the dominant structural trends of the Red Sea region. Most of these dykes exhibit NNW–SSE and N–S alignments, reflecting the regional tectonic regime. However, a smaller subset of dykes diverges from these dominant trends, displaying NNE–SSW orientations, and such trends could be attributed to subsequent deformational events. This structural configuration highlights the dynamic geological history of the area and its relationship with the Red Sea tectonic evolution.

Major faults and folds of regional extent have been recognized in the studied area18,19. However, few attempts of regional structural studies as a potential exploration tool have been made to relate mineralization to structure20,21,22,23.

The Egyptian Authority for Surveying and Mining studied the regional structure of this area to identify the overall structures in the area by using an interpretation of the aerial photographs complemented by land satellite imagery24. This study concluded that the studied area is highly fractionated being affected by numerous fractures (Faults and joints) of variable extensions and orientations decorating the area by a brecciated like fracture pattern.

Fracturing plays a key role in shaping the topography of the area. Most of the wadis follow the regional fault trends, and the steepness and ruggedness of the mountains are mainly due to the various fractures that cut through the region. A clear example of how the structures control the landscape is the Esh El Mellaha range, which is believed to have formed along a straight topographic line that follows the NNW–SSW fracture system. The area is generally intersected by several fracture sets, primarily trending NNW–SSE, NNE–SSW, ENE–WSW, E–W, and N–S. The metavolcanic rocks display well-developed ductile structures, including minor folds, alongside prominent primary structures, with these secondary features also being clearly observed.

This Bouguer gravity anomaly map serves as a valuable tool for understanding subsurface geology. By analyzing the distribution and intensity of gravity anomalies, researchers can identify potential tectonic structures, subsurface cavities, dense rock formations, volcano-sedimentary complex and sedimentary basins25,26,27,28,29. The integration of borehole data with modeled profiles enhances the reliability of geological interpretations, making it a critical step in mineral exploration, tectonic studies, or hydrocarbon prospecting. The total aeromagnetic intensity anomaly map (RTP) reveals significant variations in magnetic properties across the study area. High magnetic zones indicate dense, magnetic rock formations, while low magnetic zones suggest sedimentary or weathered regions. The borehole data and modeled profiles enhance interpretation by providing a deeper understanding of subsurface structures. This map is invaluable for tectonic studies, mineral exploration, and subsurface geological mapping25,26,27,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Recent advancements in the acquisition, processing, and interpretation of potential field data have made gravity and magnetic techniques increasingly valuable and cost-effective tools for exploration. These methods are particularly useful for identifying and delineating structural features within both the basement and the sedimentary sections. With continuous improvements in high-resolution magnetic data, it is now possible to detect hydrocarbon-related structures, even in areas with weakly magnetic sedimentary rocks.

The global significance of this research lies in its contribution to the understanding of the structural and tectonic framework of the Esh El Mellaha area, a critical region within the Red Sea Basin known for its potential hydrocarbon resources. By integrating advanced geophysical techniques—such as Bouguer gravity and aeromagnetic data analysis, as well as 2D and 3D modeling—the study provides valuable insights into the subsurface geology, including the depth and configuration of the basement surface and sedimentary cover. These findings enhance our knowledge of the area’s tectonic evolution, structural features, and sedimentary accumulation, which are essential for hydrocarbon exploration and resource assessment. Furthermore, the methodology and results offer a model that can be applied to similar tectonic and sedimentary settings globally, contributing to the broader field of geophysical and geological research.

Geologic setting

The Gulf of Suez is a well-researched failed rift basin located at the northern arm of the triple junction with the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden5,7,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. This region was shaped by the rupturing of the continental lithosphere due to asthenospheric upwelling, and features a distinct tectonic framework45,46. The tectonic map shown in Fig. 1B highlights three key fault-bounded zones: the Darag Basin in the north, the Belayim Province centrally, and the Zeit Province in the south6,47,48 The basin is dominated by NNW-trending extensional faults and houses numerous productive hydrocarbon fields.

The studied area is characterized by diverse surface geological structures that reflect a complex tectonic and geological history (Fig. 1C). The region is dominated by major fault systems trending in a northwest-southeast direction, which aligns with the prevailing tectonic regime associated with the opening of the Gulf of Suez. These faults play a significant role in shaping the surface distribution of sedimentary and volcanic rocks. The exposed geological formations in Ash El Mellaha include sedimentary sequences from the Tertiary and Quaternary periods, alongside evidence of metamorphic and basement rocks at depth (Fig. 1D). Surface geological structures such as folds, fractures, and fault scarps are prominent, indicating the impact of extensive tectonic movements. These structures provide valuable insights into the regional stress patterns and deformation history.

The investigated area is in the southwestern part of the Gulf of Suez region and includes both onshore and offshore oil fields. The stratigraphic section of the area spans from the Cambrian to the Miocene, with an unconformity separating the overlying layers from the crystalline Precambrian basement rocks. Surface exposures in the region also include the Neoproterozoic basement complex, consisting of metamorphic and igneous rocks, which outcrop at the Gable El-Zeit and Esh El Mellaha ranges49.

The area of study also includes Eocene, Miocene, Plio-Pleistocene and Recent successions. The Neoproterozoic basement in the region is akin to the Pan-African Belt. The exposed rocks encompass calc-alkaline metavolcanics, Dokhan Volcanics, post-amalgamation Hammamat Sediment, late-tectonic granites and metgabbro-diorite complex, along with ring complexes. The basement is covered by Phanerozoic succession. The overall geological characteristics of the area, including magmatic activity and the facies of the volcano-sedimentary sequences, suggest that it belongs to an island arc and active continental margin environment. Figure 2 is a simplified stratigraphic chart representing the geological framework of the Gulf of Suez Basin, as described by Bosworth and McClay48. The chart is organized into the following columns:

-

Rifting and stratigraphic division: The basin’s stratigraphy is divided into Pre-Rift Sediments, Syn-Rift Sediments, and Post-Rift Sediments, reflecting the tectonic evolution of the area. The Pre-Rift section includes formations from the Precambrian basement up to the Paleozoic and early Mesozoic. The Syn-Rift section records sediments associated with basin development during the Cretaceous to Miocene, while the Post-Rift represents younger deposits.

-

Age and rock units: The chart spans geological time from the Precambrian to the Recent-Pliocene, including systems such as the Cambrian, Carboniferous, Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Cenozoic. Each system is further divided into series, stages, and specific rock units.

-

Lithology: The lithological column shows a variety of rock types, including shale, limestone, sandstone, dolomite, conglomerate, and evaporites such as anhydrite and salt. The color-coded legend provides an easy visual reference to identify the rock types.

-

Environmental cycles: This column highlights the depositional environments, transitioning between continental, shallow marine, and deep marine settings. The arrows indicate the progression of marine incursions and regressions over time.

-

Thickness: The thickness of each stratigraphic unit at its type of section is provided in meters, showing the significant variation in sedimentary accumulation.

-

Hydrocarbon potential: The chart identifies hydrocarbon-related properties such as source rocks, reservoir rocks, and seals for each unit. For example, formations like South Gharib (seal) and Zeit (source) are critical for hydrocarbon exploration in the basin.

-

Key observations: The rift-related sequences, particularly in the Miocene, are significant for hydrocarbon systems, with thick salt and anhydrite layers acting as seals. The Pre-Rift sediments, including Nubian sandstone and carbonate rocks, provide excellent reservoir potential. Environmental cycles demonstrate a dynamic depositional history influenced by tectonics and marine transgressions.

Simplified stratigraphic chart representing the geological framework of the Gulf of Suez Basin, as described48. This chart provides a detailed summary of the geological framework of the Gulf of Suez Basin. It represents stratigraphy, lithology, environmental cycles, hydrocarbon potential, and thickness variations within the basin.

The syn-rift Miocene mega-sequence of the Gulf of Suez is typically sub-divided into two main groups: (1) the basal Lower Miocene Gharandal Group (Fig. 2) (2) the Middle–Upper Miocene Ras Malaab Group, which overlies it. Both groups have potential for hydrocarbon exploration. The upper group provides an excellent seal for pre-rift and Miocene targets, while the lower group contains well-defined reservoirs that were deposited in favorable structural settings, along with source rocks rich in organic matter37. These two groups have a cumulative thickness approximately twice that of the pre-Miocene rock strata, suggesting a predominantly constrained depositional environment within a rapidly subsiding graben.

Material and methods

Data used

Bouguer gravity map (Fig. 3) was prepared by the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC) in 1977 as part of the project of establishing the gravity map of Egypt at a scale of 1:100,00053. This extensive initiative aimed to systematically map Egypt’s gravitational field to improve the understanding of subsurface geological structures. The map, compiled by EGPC’s geophysical department, was based on gravity surveys conducted across various regions of the country. The anomalies were calculated using the International Gravity Formula of 1967 and referenced to the national gravity reference network established in 1977. Bouguer corrections were applied using a standard density of 2.3 g/cm3, ensuring accurate representation of gravitational variations across Egypt.

Bouguer gravity anomaly map of the Esh El Mellaha area, Gulf of Suez, Egypt, illustrating gravity variations related to subsurface gravity anomalies. The color scale (in mGal) represents gravity anomaly values, with high-gravity regions shown in warm colors (red, pink) and low-gravity regions in cool colors (blue, green). The map highlights major geological formations, including Dokhan volcanics, Hammamat sediments, older granitoids, and metavolcanics. Structural lineaments (white dashed lines) indicate fault zones and tectonic trends. Borehole locations (black stars) and modeled profiles (black lines) are also displayed. The rose diagram represents the dominant structural orientations. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Total magnetic intensity (TMI) map was surveyed using aeromagnetic methods by the aeroservice division of the western geophysical company of America. The data were acquired with a proton magnetometer offering a resolution of 0.01 nT, at an average flight altitude of 120 m above the terrain The survey utilized a series of parallel flight lines spaced 1.0 km apart, oriented in a NE–SW direction. Measurements were recorded at a sampling interval of 91 m (AeroService, 1984). The collected data were corrected for the International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF), converted into (x, y, z) coordinates, and gridded at a 250-m interval. TMI map was proceesed to be converted into reduced to the pole (RTP) map (Fig. 4).

Reduce to the pole (RTP) aeromagnetic map for the investigated area. The RTP transformation shifts magnetic anomalies directly over their sources by compensating for the effects of Earth’s magnetic inclination, providing a clearer representation of subsurface structures. The color scale (in nT) indicates variations in magnetic intensity, with high values (red, pink) corresponding to magnetized bodies and low values (blue, green) representing less magnetic or non-magnetic materials. The map has been processed to shift magnetic anomalies directly over their causative sources. This correction accounts for the inclination (39.5) and declination (2) of the Earth’s magnetic field. Major geological units, including Dokhan volcanics, Hammamat sediments, older granitoids, and metavolcanics, are labeled. Structural lineaments (white dashed lines) highlight fault zones and fractures. Borehole locations (black stars) and modeled profiles (black lines) are also marked. The rose diagram illustrates the dominant structural orientations. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Two wells’ datasets (QQ89-4 and West Eshmallaha wells were used to validate the potential field interpretations.

Methodology

Data processing

The final output consisted of total intensity aeromagnetic data, was reduced to the pole (RTP) for the study area using inclination of 39.5° N, and declination of 2.0° E (Fig. 4). Performing RTP is essential for obtaining geologically meaningful magnetic interpretations. It simplifies anomaly patterns, aligns them with their sources, and makes comparisons easier, particularly in regions where the Earth’s field is not vertical.

Bouguer gravity and RTP magnetic maps were filtered to separated the effect of the regional anomalies from those of the shallower ones. The first vertical derivative (FVD) technique of gravity data was used as a widely filtering technique that enhances shallow geological features and provides better resolution of near-surface density variations. It is particularly useful in geophysical exploration for highlighting the structural and lithological boundaries. The FVD amplifies short-wavelength (high-frequency) anomalies associated with shallow density variations. It suppresses the effects of deep-seated structures and regional gravity and magnetic trends, making near-surface features clearer. It highlights faults, contacts, and geological boundaries because the derivative enhances changes in gravity and magnetic anomalies, the results were illustrated in Fig. 5. On the other hand, Low-pass filter (regional) map of the investigated area, was constrcuted highlighting broad, deep-seated geological structures. The low-pass filtering technique isolates regional gravity and magnetic trends by removing short-wavelength anomalies associated with near-surface sources, revealing deep-seated features. The results were illustrated in Fig. 6.

First vertical derivative (FVD) maps of the investigated area using gravity data (A) and magnetic data (B), highlighting gradient variations to enhance the interpretation of shallow subsurface structures. The color scale represents the rate of change of gravity anomalies (mGal/m) and magnetic field intensity (nT/m), where high-gradient zones (red, pink) indicate faulted or lithological boundaries, while low-gradient zones (blue, green) correspond to more uniform subsurface structures. Major geological formations, including Dokhan Volcanics, Hammamat Sediments, Older Granitoids, and Metavolcanics, are labeled. Structural lineaments (white dashed lines) represent major fault trends, borehole locations (black stars) indicate well positions, and modeled profiles (black lines) show interpreted cross-sections. The rose diagram illustrates the dominant structural orientations in the area. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Low-pass filter (regional) anomaly maps of the investigated area, representing deep-seated subsurface structures by filtering out high-frequency (shallow) anomalies. (A) Gravity anomaly map, where the color scale (in mGal) indicates gravity variations, with higher values (red, pink) corresponding to denser geological formations and lower values (blue, green) representing less dense regions. (B) Magnetic anomaly map, where the color scale (in nT) highlights variations in magnetic intensity, with high values (red, pink) indicating magnetized bodies and low values (blue, green) representing less magnetic or non-magnetic materials. Both maps label major geological units, including Dokhan volcanics, Hammamat sediments, older granitoids, and metavolcanics. Structural lineaments (white dashed lines) mark deep-seated fault trends and fractures, while borehole locations (black stars) and modeled profiles (black lines) are also displayed. The rose diagrams illustrate the dominant structural orientations. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Terracing of potential field data

The “terracing” method is a geophysical data processing technique introduced by Cordell and McCafferty54. It transforms potential field data, such as gravity or magnetic data, into distinct domains characterized by abrupt boundaries. These domains represent regions of uniform physical properties, such as density or magnetization. For magnetic data, a pseudogravity transformation is applied before terracing. This method, often used in conjunction with horizontal gradient maxima, helps delineate subsurface body boundaries, making it valuable for structural and geological interpretation. The results were shown in Fig. 7.

This figure presents two profiles illustrating the horizontal boundaries of source bodies derived from gravity and magnetic data using the terracing method. (A) (Gravity Profile): The observed gravity profile (red line) is matched with the terraced model (black dashed line), highlighting the horizontal boundaries of gravity anomaly sources. The profile indicates variations in subsurface density contrasts. (B) (Magnetic Profile): The Reduced-to-the-Pole (RTP) magnetic profile shows magnetic anomaly boundaries. The terraced model aligns with the observed magnetic data, emphasizing zones of contrasting magnetic susceptibilities. This figure aids in identifying structural boundaries and subsurface features potentially linked to geological structures, providing insight into the region’s tectonic framework. These figures were prepared using U.S. Geological Survey Potential-Field Software Package81.

Depth estimation

Depth estimation was conducted using three geophysical techniques: Werner deconvolution, Euler deconvolution and analytical signal analysis. These methods were applied to determine the depths of the sources responsible for the observed anomalies. Each technique contributed unique insights into the subsurface structure, ensuring a more accurate and reliable interpretation of the depth to these anomalies.

Euler deconvolution

The 3D Euler deconvolution technique is used to estimate both the depth and location of the sources of anomalies by solving Euler’s homogeneity equation (Eq. 1), which relates potential fields (gravity or magnetic) to their sources under the influence of a background field. This mathematical approach is widely referenced in geophysical studies34,55,56,57,58. The methodology provides a framework for interpreting subsurface structures and identifying the spatial characteristics of anomalous bodies.

The variable (P) represents the observed magnetic or gravity field data at a specific point (x,y,z). The directional derivatives of the field, (∂P/∂x, ∂P/∂y, ∂P/∂z) are computed using techniques such as convolution or Fourier domain calculations. The coordinates (x0, y0, z0) define the anomaly source location, where z0 is the depth, while (B) is the background field. The structural index (N) quantifies the homogeneity of the field, with values linked to specific source geometries59. Correctly determining N is crucial for accurate depth estimation and relies on geological context60,61. Various computational methods have been developed for structural index determination (e.g.,62,63,64,65,66. Table 1 highlights key structural index values for simple, homogeneous geological structures.

By examining the Euler Eq. (1), we see that N controls the rate of decay of gravity and the magnetic field with distance from the source. When N is large, the field falls off at a greater rate than for small N. The structural index 1 was used for both gravity and magnetic data to locate the depth of the subsurface causative bodies (faults and contacts), and the results are shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

Euler depth solutions for (A) gravity and (B) magnetic sources, both computed using a structural index of 1, a maximum depth tolerance of 10%, and a window size of 5. Depth values are color-coded, with shallow sources (< 500 m) represented in black and deeper sources (> 3500 m) shown in blue. These depth estimations provide insights into the subsurface structural framework and potential geological features. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Depth estimation using the Source Parameter Imaging (SPI) technique, where (A) represents the depth to gravity sources and (B) corresponds to magnetic sources. The color-coded map illustrates depth variations, with warmer colors (red to purple) indicating deeper sources and cooler colors (blue to green) representing shallower sources. The SPI method enhances depth estimation accuracy by analyzing local wavenumber maxima, enabling the identification of subsurface structures without prior assumptions about source body thickness. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Source parameter imaging (SPI) method

The Source Parameter Imaging (SPI) method, also known as the local wavenumber technique, is an approach for estimating magnetic source depths by extending the concept of the complex analytical signal. This method utilizes the local wavenumber function67, which is mathematically defined by Eq. (2):

For a dipping contact, the maxima of k are positioned directly above the edges of the isolated contact and remain unaffected by magnetic inclination, declination, dip, strike, or remnant magnetization. The depth at the source edge is estimated using Eq. (3), which is derived from the reciprocal of the maximum local wavenumber:

where kmax is a peak value of the local of number k over the step source.

The local wavenumber method allows depth estimation without requiring assumptions about the thickness of the source bodies, as it identifies maxima over isolated contacts68. Phillips69 compared the SPI method with the analytical signal method, highlighting differences in their assumptions, accuracy, and sensitivity to noise and anomaly interference.

Analytical signal method

The analytical signal (AS) method, also known as the total gradient method, is widely used for delineating the edges of magnetic source bodies. This approach is implemented using Geosoft Oasis Montaj Software, ver, 8.452. According to69,70 and Roest et al.71, the AS method assumes that magnetic sources are isolated dipping contacts separating thick geological units. The magnitude of the analytical signal is mathematically defined as the square root of the sum of the squared vertical and horizontal derivatives of the magnetic field, as described by72 in Eq. (4):

A key advantage of the AS method is its independence from magnetic inclination when estimating magnetic parameters from anomalies. The effectiveness of this method lies in its ability to accurately determine both the location and depth of magnetic sources with minimal assumptions about their nature. Typically, the magnetic source is considered a 2D structure, such as a step, contact, horizontal cylinder, or dike. For these geological models, the amplitude of the analytical signal exhibits a bell-shaped symmetric function centered directly above the magnetic source.

The depth to the magnetic source is determined by the ratio of the total magnetic AS to the first vertical derivative analytical signal (AS1) of the total magnetic field, as presented in Eq. (5):

where

FVD represents the first vertical derivative of the Reduced-to-Pole (RTP) data.

The depth to the magnetic source is then calculated using Eq. (6):

where

D is the depth to the magnetic source. N is the structural index, which depends on the geometry of the magnetic source. For example, N = 4 for a sphere, N = 3 for a pipe, N = 2 for a thin dike, and N = 1 for a magnetic contact (Reid et al., 1990).

The outcomes of applying this technique to gravity and magnetic data are presented in Fig. 10A and B.

(A) Depth map of gravity sources derived using the Analytical Signal method, with color coding indicating variations in anomaly depths—warmer colors (red, orange) represent shallower sources, while cooler colors (blue, green) depict deeper sources. This analysis enhances the identification of density variations in subsurface structures. (B) Depth map of magnetic sources obtained through the Analytical Signal method, using a similar color scheme to highlight depth variations. The results provide crucial insights into the subsurface geological framework and potential structural formations. These figures were prepared using Geosoft Oasis Montag Software ver. 8.452.

Modeling of gravity and magnetic data

Two and half dimension modeling

After completing the depth estimation, 2.5D modeling using SAKI subroutines73 was employed to calculate gravity and magnetic fields. The goal of the forward modeling is to define anomaly source body parameters, with each 2D profile modeled as elongated polygons characterized by size, shape, depth, and other properties. Iterative modeling continues until the best fit between observed and calculated anomaly curves is achieved. Different authors74,74,75,77 explore the approaches quite extensively. Due to the non-uniqueness of potential field data, geological and geophysical constraints, such as borehole logs and seismic data, are used to enhance the model’s accuracy. The study assumes constant magnetization and density contrast due to poor seismic data quality. Nonlinear separation methods, similar to surface fitting, allow for modeling anomaly-causing mass distributions, with simplified models such as polygonal bodies or rectangular blocks. Both magnetic and gravity data are used in these 2D studies, with the magnetic profiles corrected by removing the International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF).

Gravity and magnetic modeling were performed along two selected profiles, integrating borehole data with earlier results. And the findings are illustrated in Figs. 9 and 10

For 3D gravity inversion modeling, density contrast variations were used to map the gravity anomaly sources’ tops and bottoms. Simultaneously, magnetic anomalies were modeled as three-dimensional dipole sources to enhance the subsurface interpretation.

Three-dimension modeling

The author applied GI3 software to perform 3D gravity inversion by the iterative method of76 where 3D gravity inversion is performed. This method is a well-known approach for interpreting gravity data to model the subsurface structures. This method involves iteratively adjusting the model to best fit the observed gravity data, effectively solving for the density distribution that would produce the observed gravitational field. GI3 software likely automates this iterative process, allowing for efficient and accurate inversion of gravity data in three dimensions. Input is a standard grid gravity file with a maximum array size of 50 by 50. The derived model is defined in terms of a reference surface, normally a plane, defining the top, base, or midsection of the body. The output files include the model (thickness) surface (top or bottom), the calculated gravity effect of the model, and the residual gravity error.

On the other hand, the author applied 3D magnetic inversion modeling using Magpick software to estimate the location of magnetic sources. Presently MagPick allows two kinds of sources: Magnetic dipole which is good for a local magnetic source(s) and magnetic line which fits objects like pipes. The geometrical location and amplitude of the source can be found. Results of estimations are viewed as worksheets and can be saved or loaded from files as well as exported. Along with the simple magnetic picking facilities, MagPick has an internal option for magnetic modeling. Presently it supports only three kinds of sources-uniform magnetized sphere, (magnetic dipole), magnetized line, and uniform infinite current (power line). It is possible to find a few sources simultaneously (in case of dipoles or power lines). Parameters that need to be estimated for each dipole are three components of the total magnetic moment of the body and three parameters (X, Y, Z) of its geometrical location. In addition, a simple function to fit the background field can be found, because this method can be applied directly to the measured field without calculation of the residual field.

3D inversion

Gravity and magnetic inversion are fundamental geophysical techniques used to model subsurface structures by analyzing gravity and magnetic field data. These methods help determine variations in density and magnetization within the Earth’s crust by solving inverse problems, which aim to minimize discrepancies between observed and predicted anomalies35,78,79, Pygimli, a Python-based library, provides a comprehensive set of tools for gravity and magnetic inversion, incorporating numerical solvers and optimization algorithms. Gravity inversion relies on Bouguer’s equation to establish a relationship between gravity anomalies and density variations, while magnetic inversion utilizes equations involving magnetization and field gradients. These equations serve as the basis for forward modeling, which is then inverted to estimate subsurface properties. To ensure accuracy and stability, various inversion methods and regularization techniques are applied35,78,79.

This study applies 3D gravity inversion modeling using the Pygimli library to investigate subsurface structures in the region. The inversion process utilizes Bouguer gravity data with a spatial resolution of 1 km in the X, Y, and Z dimensions, extending to a depth of 15 km to capture critical geological features and potential mineral deposits. By leveraging Pygimli’s robust and customizable framework, this study effectively maps subsurface density variations, revealing density values ranging from 1.5 to 1.7 gm/cc, with a background density of 2.67 gm/cc and an error margin of 2.6%.

Additionally, the Pygimli library is employed for 3D magnetic inversion modeling to further investigate the region’s subsurface structures. The magnetic inversion process utilizes survey data with a cell size of 1 km in the X, Y, and Z dimensions and extends to a depth of 10 km to capture key geological features and potential mineral deposits. By utilizing Pygimli’s flexible framework, this study provides valuable insights into subsurface magnetic properties. The inversion results indicate magnetic susceptibility values ranging from -0.110 to 0.046 SI, with an error margin of 3.02%, offering critical information on subsurface structures, mineral deposits, and geological anomalies of economic significance.

This methodology and the accompanying code were utilized in80, demonstrating the effectiveness of Pygimli in 3D gravity and magnetic inversion for geological investigations.

Results and discussion

Interpretation and analysis of Bouguer gravity anomaly map (Fig. 3) reveals minor variations in gravity values within the study area, ranging from − 36 to 12 mGal. This map is used to study gravity variations caused by subsurface geological structures. The color scale (in mGal) represents gravity anomaly values. Warm colors (red and pink) indicate high-gravity regions, which are often associated with dense geological formations like mafic or ultramafic rocks, volcanic intrusions, or basement structures. Cool colors (blue and green) indicate low-gravity regions, typically linked to less dense formations, such as sedimentary basins, fault zones, or regions with significant crustal thinning. The map highlights several important geological formations, including Dokhan volcanics (igneous rock formations known for their high density, typically linked to ancient volcanic activity), Hammamat sediments (sedimentary deposits that tend to have lower density, contributing to gravity lows), Older granitiods and metavolcanics (form the basement complex and influence gravity anomalies due to their varied densities).White lines represent structural lineaments, indicating fault zones and tectonic structures. These faults can control the subsurface distribution of rock formations. The rose diagram in the lower-right corner represents the dominant structural orientations in the area where the main trend is NNW–SSE (Gulf of Suez trend). It provides insights into regional tectonic stress patterns, which influence faulting and geological formations.

Analysis and interpretation of RTP map

Analysis and interpretation of the aeromagnetic map reduced to the pole (Fig. 4) exhibits a broader range, from 41,600 to 42,800 nT, highlighting alternating negative and positive anomalies caused by different subsurface sources in the basement and sedimentary rocks. This map is used to interpret subsurface magnetic structures by removing the inclination effect, allowing anomalies to be positioned directly over their sources. The color scale (in nT, nanotesla) represents magnetic intensity values. High-magnetic regions (pink, red, orange): Indicate the presence of magnetized geological formations, such as igneous intrusions, metavolcanics, or basement rocks. Low-magnetic regions (blue, green): Suggest non-magnetic or weakly magnetized formations, often corresponding to sedimentary basins or faulted zones. Dokhan Volcanics (high-magnetic, pink/red): These are igneous formations with strong magnetization due to their volcanic origin. Hammamat Sediments (low-magnetic, blue/green): These are non-magnetic sedimentary deposits, consistent with their low-density nature in the gravity map. Older Granitoids & Young Granitoids: The magnetization of these granitic formations varies depending on their mineral composition and alteration. W. Abu Had Metavolcanics: These rocks show moderate to high magnetic responses due to their metamorphosed volcanic origin. White lines indicate faults and structural lineaments, showing tectonic movements and subsurface fractures. The rose diagram in the lower right corner represents dominant structural orientations, similar to the one in the gravity map where the main trend is NNW–SSE (Gulf of Suez trend).

By comparing the RTP magnetic map with the Bouguer gravity anomaly map: High-magnetic and high-gravity regions (red/pink in both maps): Likely represent dense and magnetized igneous intrusions, such as Dokhan volcanics and older granitic. Low-magnetic and low-gravity regions (blue/green in both maps): Correspond to less dense and non-magnetic sediments, such as Hammamat sediments. Fault zones (white lines): Appear in both maps, confirming their structural significance. The alignment of magnetic and gravity anomalies suggests major fault-controlled geological structures. High-magnetic and high-gravity zones may indicate potential ore deposits or hydrothermal mineralization. Low-gravity and low-magnetic regions (sedimentary basins) may be potential hydrocarbon reservoirs.

First vertical derivative (FVD( maps

First vertical derivative (FVD( maps (Fig. 5a and b) are combination multiple datasets—including gravity anomalies, magnetic responses, and structural mapping—to provide a more comprehensive view of the shallow subsurface geology. Key elements such as color gradients, structural lineaments (often indicated by white lines), borehole locations (marked with symbols), and modeled cross-sectional profiles are present. These elements help delineate the boundaries and variations of different geological units. Similar to the previous maps, the color scheme in this figure likely represents variations in physical properties: Warm colors (reds and pinks): Correspond to zones of high gravity and strong magnetic responses. These suggest the presence of dense and magnetized rocks, such as igneous intrusions or basement complexes (e.g., Dokhan volcanics or older granitic units) which indicated by Esh El Mallaha Range. Cool colors (blues and greens): Indicate areas of lower density and weak magnetization, which are typically associated with sedimentary basins or faulted zones (e.g., Hammamat sediments and sedimentary rocks). The figure shows prominent structural lineaments and fault zones. These are crucial for understanding the tectonic framework and help explain the distribution of gravity and magnetic anomalies. For example, the alignment of these faults may control the juxtaposition of dense basement rocks against overlying, less-dense sediments.

In both the gravity and RTP magnetic maps, high anomaly zones were associated with dense and strongly magnetized features. In the integrated figure, these areas are reinforced by corresponding features in the composite interpretation. They likely represent regions dominated by igneous intrusions or uplifted basement blocks. Areas showing low gravity and weak magnetic signals in the previous maps are interpreted in the integrated figure as sedimentary basins or zones affected by faulting. These areas are characterized by thicker sedimentary deposits, which are less dense and exhibit minimal magnetic susceptibility. The integrated map emphasizes the role of faults and structural lineaments that were also evident in both the gravity and magnetic datasets. Their consistent presence across all datasets supports a tectonically active history in the study area, influencing the distribution and juxtaposition of different lithologies.

The integration of datasets underlines a tectonically complex environment where faulting and fracturing have a significant impact on subsurface architecture. The alignment of these structures helps in understanding the regional stress regime and the evolutionary history of the Gulf of Suez rift system. The combination of high-density/magnetization zones with fault-controlled sedimentary basins provides a roadmap for exploration. High-anomaly regions might be prospective for ore deposits linked to igneous intrusions. The sedimentary basins, identified by their lower anomaly signatures and faulting, could indicate potential reservoirs. Boreholes included in the figure serve as critical validation points that tie the geophysical interpretations to actual subsurface conditions, ensuring that the interpretations derived from gravity and magnetic data are reliable.

Analysis and interpretation of the Low-Pass filter

Analysis and interpretation of the Low-Pass filter (Regional) gravity and magnetic anomaly maps (Fig. 6), which emphasize deep-seated subsurface structures by eliminating high-frequency (shallow) anomalies. This process helps in identifying large-scale geological features that are critical for understanding the regional tectonic framework.

Gravity Anomaly Map (Panel A): High gravity values (red, pink): Indicate dense geological formations, such as igneous intrusions, granitic bodies, and basement highs. Low gravity values (blue, green): Represent less dense regions, commonly associated with sedimentary basins or faulted zones. High density regions align with Dokhan volcanics and older granitoids, confirming their presence as dense, uplifted crustal blocks. Lower-density zones coincide with Hammamat sediments and sedimentary rocks, supporting their interpretation as less dense and potentially thicker sedimentary deposits. Several structural lineaments (white lines) are visible, marking deep-seated faults and fractures that control the subsurface architecture.

Magnetic anomaly map (panel B): high magnetic intensity (red, pink) indicates strongly magnetized bodies, typically associated with mafic or volcanic rocks. Low magnetic intensity (blue, green) suggests non-magnetic or weakly magnetized materials, such as sedimentary deposits or altered rocks. Dokhan volcanics exhibit strong magnetic anomalies, confirming their mafic-rich composition. Hammamat sediments show weak magnetization, reinforcing their classification as sedimentary units. The presence of deep-seated faults (white dashed lines) suggests that tectonic activity has played a significant role in shaping the magnetic structure of the area.

Correlation with previous gravity and magnetic maps

The low-pass filter gravity map (Panel A) confirms deep-seated crustal features that were previously inferred from the Bouguer gravity anomaly map. The low-pass filter magnetic map (Panel B) aligns well with the RTP magnetic anomaly map, but with a greater focus on regional tectonic features rather than shallow anomalies. Structural trends observed in previous maps (e.g., dominant fault orientations in the rose diagram) are consistent with those seen here, further validating the geological framework. The alignment of deep-seated anomalies with known fault zones suggests that faulting has controlled the distribution of rock units and may be linked to the extension of the Gulf of Suez Rift.

Figure 7 demonstrates the delineation of horizontal boundaries for gravity and magnetic source bodies using the terracing method. The upper panel illustrates the observed gravity profile, while the lower panel shows the Reduced-to-Pole (RTP) magnetic profile. The red line represents the observed profiles, while the dashed blue line highlights the calculated horizontal boundaries of the source bodies. This method effectively identifies distinct shifts in amplitude, marking transitions between source bodies of varying densities and magnetizations. These interpretations are critical for mapping subsurface geological structures and distinguishing between sedimentary and basement rocks.

Analysis and interpretation of Euler depth solutions for gravity and magnetic sources

Figure 8 presents Euler depth solutions for gravity (A) and magnetic (B) sources, providing insights into the depth distribution of subsurface structures. Euler deconvolution is a well-established technique used to estimate the depth of potential field sources, which helps in understanding fault structures, basement relief, and geological contacts. Shallow sources (< 500 m, black dots): Represent near-surface structures, possibly linked to faulted sedimentary layers, recent intrusions, or shallow fractures. Intermediate depths (500–3500 m, yellow, green, cyan dots): These solutions likely correspond to major faulted blocks, contact zones, and basement undulations. Deep sources (> 3500 m, blue dots): Indicate deep-seated structures, such as crustal faults, deep intrusive bodies, or basement-rooted tectonic features.

-

Gravity-Based Euler Depth Solutions (Panel A): The gravity depth solutions (A) primarily highlight density variations in the subsurface. Major subsurface lineaments (pink lines) align with gravity depth solutions, suggesting that these features correspond to deep-seated faults and density contrasts (e.g., basement faults or intrusive contacts). The concentration of deep sources (> 3500 m) in some regions suggests the presence of thick sedimentary basins or deep-rooted structural features. Shallow depth solutions are concentrated along known faults and geological boundaries, indicating fault-controlled subsurface structures.

-

Magnetic-Based Euler Depth Solutions (Panel B): The magnetic depth solutions (B) reflect magnetized rock bodies, such as igneous intrusions, volcanic sequences, and basement-related faults. The alignment of deep magnetic sources with fault zones suggests that some faults extend deep into the basement, controlling the emplacement of magnetized rock formations. Shallow magnetic sources (< 500 m) are more dispersed than gravity sources, indicating near-surface magnetic anomalies related to shallow intrusions, dikes, or volcanic features.

-

Correlation with previous gravity and magnetic anomaly maps: The deep gravity solutions align with low-gravity regions (previous Bouguer and low-pass filter maps), confirming the presence of thick sedimentary deposits or fault-controlled depressions. The deep magnetic solutions correlate with high-magnetic anomalies, supporting the interpretation of deep-seated intrusive bodies or magnetized basement highs. The fault structures identified in previous maps (white lines in earlier figures) are further validated by the Euler depth solutions, confirming their significance in regional tectonics.

-

Geological and Tectonic Implications: The identified deep faults suggest a strong link between tectonic activity and subsurface geological features, likely associated with rift-related faulting in the Gulf of Suez region. The combination of deep gravity and magnetic sources may indicate potential mineralization zones, geothermal prospects, or hydrocarbon reservoirs. The alignment of Euler depth solutions with structural lineaments suggests that major faults act as conduits for magma emplacement and fluid migration, influencing mineralization and petroleum systems.

Analysis and interpretation of depth solutions from Source Parameter Imaging (SPI) for gravity and magnetic sources

Figure 9 presents depth estimations using the Source Parameter Imaging (SPI) technique for both gravity (A) and magnetic (B) data. SPI is an advanced depth estimation method that calculates depth to subsurface sources based on the local wavenumber of the potential field anomaly. These results can be directly correlated with the Euler deconvolution depth solutions (previous figure—Fig. 8), offering a comparative perspective on fault structures, intrusive bodies, and basement relief. The deep-seated structures (> 3000 m, shown in blue-purple zones) in the SPI depth maps align with the deep solutions from Euler deconvolution, confirming the presence of major faulted basement blocks and intrusions. The shallow anomalies (< 500 m, red-pink regions) correspond to sedimentary cover variations, surface-near fault zones, and intrusive bodies, similar to what Euler depth solutions indicated.

Analysis and interpretation of depth solutions from Analytical Signal for gravity and magnetic sources

Figure 10 is based on the analytical signal method, which is used to determine the depths of gravity and magnetic sources in the study area. This technique enhances the detection of subsurface density and magnetic variations. Depths are represented using a color gradient, where warmer colors (red, orange) indicate shallower sources (less than 2000 m), while cooler colors (blue, green) represent deeper sources (exceeding 4000 m). Gravity depth map (A) illustrates the depth distribution of gravity sources, ranging from approximately 2000 m to over 4500 m. Red areas correspond to shallow geological structures, whereas blue regions indicate deep-seated dense formations. Magnetic depth map (B) shows the depth distribution of magnetic sources, varying between 1500 m and over 5000 m. The results help identify the extensions of igneous or metamorphic rocks beneath the surface, which influence geological structures. These analyses assist in detecting deep-seated faults and fractures, which are crucial for hydrocarbon accumulation. The data provides valuable insights into the extent of deep geological structures, supporting geological exploration and resource extraction, including oil, gas, and mineral deposits.

Analysis and interpretation 2.5 D modeling profiles

A series of figures showing each model are included herein such as Figs. 11 and 12. These figures display the configuration of the individual source bodies in the lower portion of the plot while the middle and upper portions display the observed and calculated magnetic and gravity data curves respectively. Tables listing the pertinent parameters for each source body are also included. The basement densities used in these for the rocks as given in such sources30,82,83 while the susceptibilities used represent averages as determined in the analysis of the total magnetic intensity data and the available geological information about the nature of the study area.

Results of 2.5-D modeling along profile P1, showing observed and calculated gravity and magnetic data derived from the Bouguer gravity anomaly map and the Reduced-to-the-Pole (RTP) magnetic map. The lower section depicts the geological model with labeled source bodies (B1–B8), their corresponding body types, densities (g/cm3), and magnetic susceptibilities (SI). The model highlights the configuration of basement structures, sedimentary layers, and intrusions along the profile. These figures were prepared using U.S. Geological Survey Potential-Field Software Package81.

Results of 2.5-D modeling along profile P2, showing observed and calculated gravity and magnetic data derived from the Bouguer gravity anomaly map and the Reduced-to-the-Pole (RTP) magnetic map. The geological model below illustrates labeled source bodies (B1–B8), their corresponding types, densities (g/cm3), and magnetic susceptibilities (SI), highlighting the configuration of basement structures, sediments, volcanics, and intrusions along the profile. These figures were prepared using U.S. Geological Survey Potential-Field Software Package81.

Figure 11 presents the results of the model along profile 1 (P1), which passes through wells QQ89-4 and West Eshmallaha. The basement surface configuration (source bodies B1 through B8) aligns closely with the aeromagnetic interpretation. The intrusive and volcanic bodies along the profile, labeled as "D" and "Vol," have densities set at 2.79 and 2.98 g/cm3, respectively, and are characterized by normal magnetic polarization, as evidenced by their positive magnetic susceptibility values. High-frequency anomalies along the western and northeastern sections of the profile are accounted for by the inclusion of a dyke and a volcanic source body. The basement rocks were divided into two susceptibility zones based on magnetic data. The first zone, on the western side of the model (bodies B1 through B4), has a susceptibility of 0.0037 SI. The second zone, covering bodies B4 through B8, exhibits a susceptibility of 0.0055 SI. Three significant basement structures are incorporated into the model:

-

1.

Graben Faults (B1 to B3): Two near-vertical normal faults separate bodies B1 and B2, and B2 and B3, forming a graben structure with approximately 550 m of displacement.

-

2.

Thrust Feature (B4 and B5): A tilted contact between bodies B4 and B5 is interpreted as a thrust-related feature, where body B4 originally overrode B5 before erosion produced a gentle basement rise.

-

3.

Graben Faults (B5 to B7): Two additional normal faults separate bodies B5 and B6 (545 m of displacement) and B6 and B7 (410 m of displacement), forming another graben fault pattern.

While not immediately apparent on the total magnetic field contour map, the anomaly associated with the dyke is more distinct in this profile. The modeled dyke has a limited width of approximately 2.5 km. The calculated magnetic curves closely match the observed data, with a few exceptions. Notably, a + 10 nT misfit exists near the contact between bodies B4 and B5. This misfit cannot be corrected by adjusting the configurations or susceptibilities of the basement bodies, suggesting it originates from a weakly magnetic unit within the sedimentary section rather than the basement.

For gravity modeling, a first order fit between the calculated and observed gravity traces was achieved by adjusting the densities of the six basement source bodies. However, the gravity misfit is attributed to several factors, including the sparse data spacing and the reconnaissance nature of the survey, particularly in the western part of the profile where small and structurally complex volcanic units are not captured in the observed data. Additional uncertainties arise from a lack of detailed information about the sedimentary sequences and their densities, which could not be incorporated into the model. Density variations within the sedimentary section may be more significant than the contrast between the sediments and basement rocks, leaving the precise physical sources of the gravity anomalies uncertain.

To improve the reliability of the gravity models and interpretation, more comprehensive gravity data coverage is needed, particularly in the northeastern part of the survey area. Additionally, more detailed constraints on the structural and density characteristics of the section would enhance the accuracy and relevance of the gravity modeling results.

Figure 12 illustrates the results of the modeled profile P2, which traverses west Eshmallaha well along a NNW–SSE trending line. The magnetic and gravity data for this profile were acquired and processed similarly to those of profile P1 (Fig. 9). The configuration of the basement surface, represented by source bodies B1 through B8, aligns precisely with the aeromagnetic interpretation. The model incorporates volcanic rocks (Vol.), dykes (D), and intrusive bodies (Int.), with densities set at 2.98, 2.79, and 2.60 g/cm3, respectively. All these source bodies exhibit normal magnetic polarization, as indicated by their positive susceptibility values.

The inclusion of volcanics, dykes, and intrusive bodies in the model accounts for high-frequency anomalies observed along the NNW, central, and SSE sections of the profile. The basement is divided into two susceptibility zones based on magnetic data:

-

1.

A block with a susceptibility of 0.0025 SI in the NNW portion (bodies B1 through B4).

-

2.

A block with a susceptibility of 0.0050 SI in the SSE portion (bodies B4 through B8).

Three significant basement structures are incorporated into the model:

-

1.

Northern Horst Fault System: Defined by two near-vertical normal faults separating bodies B1 and B2, and B2 and B3. These faults form a horst structure with approximately 180 m of displacement on each fault.

-

2.

Thrust Contact: A near-vertical contact between bodies B3 and B4, interpreted as a thrust-related feature. Body B3 appears to have originally overridden B4 before erosion created a gentle basement rise.

-

3.

Southern Graben Fault System: Composed of two near-vertical normal faults separating bodies B5 and B6 (700 m displacement) and bodies B6 and B7 (620 m displacement), forming a graben structure.

While the Bouguer gravity and reduced-to-the-pole (RTP) magnetic maps do not prominently display some anomalies, certain features are more easily recognized within this profile:

-

1.

Dyke anomaly: Located in the central portion of the profile with a total width of ~ 1.5 km. Modeled with a susceptibility of 0.0036 SI and a density of 2.79 g/cm3.

-

2.

Volcanic anomaly: Observed in the northern portion of the profile and marked by high-gradient contour intervals on geological and aeromagnetic maps. Modeled with a susceptibility of 0.0070 SI and a density of 2.78 g/cm3.

-

3.

Intrusion anomaly: Found in the southern portion of the profile, characterized by condensed aeromagnetic contour lines. Modeled with a susceptibility of 0.0009 SI and a density of 2.6 g/cm3.

The calculated magnetic response closely matches the observed magnetic data, with minor discrepancies in a few localized areas. This fit validates the structural and lithological interpretations derived from the modeling.

Analysis and interpretation 3D modeling profiles

Figures 13 and 14 showcase 3D gravity modeling results and gravity field calculations to investigate subsurface anomaly sources with different density contrasts. Figure 13 is 3D gravity modeling. This figure comprises four subfigures, presenting 3D models of the top and bottom surfaces of source bodies with density contrasts of 1.0 g/cm3 and 0.75 g/cm3, these contracts were taken from the average density of the sedimentary succession and the underlain basement complex. These density values were selected based on composite log data from the interface between the Precambrian basement rock and the overlying sedimentary formations. In the study area, the density of gabbroic rocks ranges from 2.70 to 3.50 g/cm3, while basaltic rocks exhibit densities between 2.70 and 3.30 g/cm3. Granitoid rocks have densities varying from 2.50 to 2.90 g/cm3. Meanwhile, the overlying Nubian Sandstone has a mean density ranging from 2.2 to 2.7 g/cm3. These models provide insights into the spatial geometry of the subsurface features:

-

(a) Top of the source body (density contrast = 1.0 g/cm3): This model displays the top surface of the anomaly source. It is visualized as a textured 3D surface, where different elevations correspond to variations in the density distribution at the top layer.

-

(b) Bottom of the source body (density contrast = 1.0 g/cm3): This model represents the bottom boundary of the anomaly source for the same density contrast. The structure of this model provides a clear idea of the depth extent and the geometry of the anomaly.

-

(c) Top of the source body (density contrast = 0.75 g/cm3): Similar to (a), this model shows the top surface of the anomaly source but for a reduced density contrast. The variation in density contrast affects the shape and extent of the anomaly.

-

(d) Bottom of the source body (density contrast = 0.75 g/cm3): This model depicts the bottom layer for the lower density contrast. Comparing this with (b) highlights how changes in density contrast influence the subsurface anomaly’s representation. These models provide crucial information about the spatial extent, depth, and density variations in the subsurface.

3D models depicting the top (upper surface) and bottom (lower surface) of the gravity anomaly sources, constructed through 3D gravity inversion analysis. The models have been generated using two density contrast values: 0.75 g/cm3 (displayed on the right side of the figure) and 1.0 g/cm3 (shown on the left side). These contrasting density values provide insight into the variations in subsurface properties, helping to identify the spatial extent and geometry of the anomaly sources. These figures were prepared using U.S. Geological Survey Potential-Field Software Package81. and Golden Surfer Software84.

Gravity field calculations (mGal) for anomaly sources with varying density contrasts. (a, b) Gravity fields for top and bottom surfaces with a 0.75 g/cm3 contrast, showing subtle variations. (c, d) Fields for the same surfaces with a 1.00 g/cm3 contrast, producing more pronounced anomalies. (e) Observed gravity field, serving as a reference for model comparison. These figures were prepared using U.S. Geological Survey Potential-Field Software Package81. And Golden Surfer Software84.

Figure 14 shows gravity field calculations. This figure contains five subfigures illustrating gravity field calculations for the models in Fig. 13 and comparing them with observed gravity data.

(a) & (b) plots represent the calculated gravity field for the 0.75 g/cm3 density contrast, corresponding to the top and bottom layers, respectively. The color gradients and contour lines provide a quantitative view of the gravity anomalies generated by the source. (c) and (d) plots display the calculated gravity field for the 1.0 g/cm3 density contrast, also corresponding to the top and bottom layers. The results reveal stronger anomalies compared to (a and b), reflecting the higher density contrast. (e) plot shows the observed gravity field, serving as a reference to evaluating the accuracy of the models. The comparison highlights how well the calculated fields (a–d) align with the real gravity data. The combination of 3D gravity modeling (Fig. 13) and gravity field calculations (Fig. 14) allows for an in-depth understanding of subsurface anomalies. By using multiple density contrasts, the study evaluates the effects of density variation on the modeled and observed gravity fields. This approach helps identify the spatial extent, depth, and geometry of the anomaly sources, contributing to more accurate subsurface interpretations.

We used only the solution of magnetic dipole using Autopick tool. The results of picking for the dipole are shown in Fig. 15a where after inversion has been completed, the results appear in the worksheet table and are plotted on the top of all maps with numbers. For inversion based on the grid sign + is used. Figure 15b shows a 3D representation of the depth to the tops of the source bodies in kilometers. Figure 15 consists of two parts illustrating the results of analyzing magnetic dipoles using a specialized software package. Figure 15a represents a magnetic map obtained through the Reduction to the Pole (RTP) technique. It shows a series of inferred magnetic dipoles as interpreted using the Autopick tool in the Magpick Software Package. The map displays a grid overlaid with black lines and arrows, which indicates the positions and orientations of the detected magnetic dipoles. These vectors are plotted on the map to provide a visual representation of the magnetic anomalies. The grid system allows precise spatial reference, ensuring accurate interpretation of the magnetic sources. Figure 15b is a 3D visualization illustrating the depth to the tops of the source bodies responsible for the magnetic anomalies. The depth is measured in kilometers and is depicted using a color gradient, where different colors correspond to varying depths. This representation provides a clear understanding of the subsurface distribution of magnetic sources. The terrain-like structure highlights the variations in depth, with peaks and valleys corresponding to shallower and deeper magnetic sources, respectively. These two figures work together to provide both spatial and depth-related insights into magnetic anomalies, making it easier to interpret subsurface geological structures. The use of advanced tools like Magpick and Autopick ensures precision in both detection and representation.

Magnetic Dipoles Analysis and 3D Representation. (A) Magnetic dipoles from the RTP magnetic map, processed with MagPickTM85 and Golden Surfer Software84. Black lines mark anomaly locations and orientations, possibly linked to lineaments. The color gradient shows magnetic intensity, with blue for low and red for high values. (B) 3D visualization of dipoles, depicting depth variations from ~ 1 (blue) to ~ 8 km (red), offering insights into subsurface structures.

Analysis and interpretation 3D inversion

Figure 16 is 3D inversion models of the study area derived from (A) gravity and (B) magnetic data. The top model (A) represents subsurface density variations (g/cm3), while the bottom model (B) illustrates magnetic susceptibility (SI). Depths range in gravity model (A) from 300 to 13,700 m (13.7 km) and from 300 to 8700 m (8.7 km) in magnetic model (B). The gravity model reveals deeper structures compared to the magnetic model, highlighting density variations at a crustal level, while the magnetic model primarily detects shallower to intermediate-depth magnetized bodies. In the gravity model (A), density values range from 2.3 to 3.7 g/cm3. Low-density regions (2.3–2.7 g/cm3) are likely associated with sedimentary deposits, fractured zones, or less dense granitic intrusions. High-density regions (3.0–3.7 g/cm3) may correspond to mafic or ultramafic intrusions, deep-seated metamorphic rocks, or dense basement structures. In the magnetic model (B), magnetic susceptibility values range from − 0.11 SI to 0.460 SI. Negative to low values (− 0.11 to 0.01 SI) suggest non-magnetic or weakly magnetized sediments and felsic rocks. Higher values (0.2–0.460 SI) indicate strongly magnetized formations, likely associated with mafic and ultramafic rocks or intrusive bodies. The comparison with previous depth estimations (Figs. 8, 9, and 10) reveals that the Euler Deconvolution, SPI, and Analytical Signal methods previously suggested shallower magnetic sources. This 3D inversion confirms that gravity sources extend much deeper than magnetic sources, reinforcing the idea that deep-seated geological formations are denser but not necessarily magnetized. The variation in magnetic susceptibility highlights differentiated igneous activity and tectonic processes in the study area. Geological Significance: The high-density (3.7 g/cm3) and high-susceptibility (0.460 SI) zones suggest the presence of dense and magnetized mafic/ultramafic intrusions, which could be related to mineralized zones. The presence of low-density and low-susceptibility regions (2.3 g/cm3, − 0.11 SI) may indicate sedimentary basins or highly altered granitic formations. The depth variations and physical property contrasts help identify major faults, intrusive bodies, and potential mineral deposits.

3D inversion models of the study area derived from (A) gravity and (B) magnetic data. The top model (A) represents subsurface density variations (g/cm3), while the bottom model (B) illustrates magnetic susceptibility (SI). Warmer colors (red, pink) indicate higher values, suggesting denser or more magnetic rock formations, whereas cooler colors (blue, green) correspond to lower-density or less magnetic regions. These models aid in identifying geological structures such as faults, intrusions, and potential mineralized zones. The data was inverted using the pyGIMLi software86, and the figures were exported using PyGMT87, a Python interface for GMT.

Figure 17 presents 3D cross-sectional views along profiles P1, P2, and P3, extracted from the 3D inversion models in Fig. 16. Panel (A) illustrates density variations (g/cm3), while panel (B) depicts magnetic susceptibility (SI). The profiles provide insights into subsurface geological structures, revealing density contrasts and magnetic anomalies indicative of faults, intrusions, and lithological variations. The dashed white lines mark subsurface lineaments, which may correspond to fault zones or structural boundaries. Profiles P1 and P2 were previously modeled in Figs. 11 and 12 using 2.5-D forward modeling, offering localized interpretations. The 3D inversion in Fig. 17 complements these models by providing a broader spatial perspective, showing the continuity and depth extent of anomalies detected along these profiles. Profile P3, newly introduced in this figure, extends the geological interpretation across the study area.

3D cross-sectional views along profiles P1, P2, and P3 extracted from the 3D inversion models in Fig. 16. (A) Density distribution (g/cm3) and (B) Magnetic susceptibility (SI). The dashed white lines represent subsurface lineaments, indicating possible fault zones or structural discontinuities. These profiles enhance the understanding of subsurface structures, with P1 and P2 corresponding to the 2.5-D forward modeling results in Figs. 11 and 12, while P3 introduces additional structural insights. Warmer colors indicate higher density and magnetic susceptibility values, suggesting denser and more magnetized formations, respectively. The data was inverted using the pyGIMLi software86, and the figures were exported using PyGMT87, a Python interface for GMT.

Figures 18 and 19 illustrate the three-dimensional distribution of subsurface density and magnetic susceptibility variations, respectively, derived from the 3D inversion results shown in Figs. 16 and 17. These figures provide an integrated view of the structural framework, highlighting density and magnetic susceptibility contrasts that correspond to different geological formations and subsurface structures. The dashed white lines in both figures indicate major subsurface lineaments, which may represent fault zones or lithological boundaries.

(A) Horizontal slices of gravity data at depths of 1000 m, 7000 m, and 13,000 m from the 3D gravity inversion cube (Fig. 16A), showing vertical density variations. (B) Vertical East–West sections along profiles P4, P5, and P6. (C) Vertical North–South sections along profiles P7, P8, and P9. The six profiles were extracted from the 3D gravity inversion model at depths of 800 m to 14,800 m to analyze horizontal and vertical density variations. The dashed white lines represent major subsurface lineaments. The data was inverted using the pyGIMLi software86, and the figures were exported using PyGMT87, a Python interface for GMT.

(A) Horizontal slices of magnetic susceptibility data at depths of 320 m, 5000 m, and 8000 m from the 3D magnetic inversion cube (Fig. 16B), illustrating vertical susceptibility variations. (B) Vertical East–West sections along profiles P4, P5, and P6. (C) Vertical North–South sections along profiles P7, P8, and P9. The same profiles (P4 to P9) were extracted from the 3D magnetic inversion model at depths of 322 to 9520 m, highlighting magnetic susceptibility contrasts. The dashed white lines mark significant subsurface lineaments, possibly indicating fault zones or lithological boundaries. The data was inverted using the pyGIMLi software86, and the figures were exported using PyGMT87, a Python interface for GMT.

Figure 18 presents the results of 3D gravity inversion. (A) Displays horizontal slices of gravity data at depths of 1000 m, 7000 m, and 13,000 m from the 3D gravity inversion cube (Fig. 16A), illustrating vertical density variations. (B) Shows vertical East–West sections along profiles P4, P5, and P6, revealing lateral density changes and structural discontinuities. (C) Presents vertical North–South sections along profiles P7, P8, and P9, emphasizing density contrasts at different depths. The six profiles (P4 to P9) were extracted from the 3D gravity inversion model at depths ranging from 800 to 14,800 m to visualize horizontal and vertical density variations.

Figure 19 presents the results of 3D magnetic inversion. (A) Displays horizontal slices of the magnetic susceptibility data at depths of 320 m, 5000 m, and 8000 m from the 3D magnetic inversion cube (Fig. 16B), illustrating vertical susceptibility variations. (B) and (C) represent the same vertical sections (P4 to P9) as in Fig. 18 but derived from the 3D magnetic inversion cube at depths of 322 m and 9520 m, highlighting magnetic susceptibility contrasts that correspond to lithological variations and structural discontinuities. The dashed white lines in both figures delineate prominent subsurface lineaments, indicating potential fault systems or lithological boundaries.

Figures 18 and 19, in conjunction with Figs. 16 and 17, provide a comprehensive visualization of the subsurface density and magnetic variations, aiding in the interpretation of the geological framework.

Figures 20 and 21 present the 3D visualization of high, low, and isosurfaces of density and magnetic susceptibility, respectively, derived from the inverted models in Figs. 16, 17, 18 and 19. These figures provide insight into the spatial distribution of subsurface density and magnetic susceptibility variations, which can be correlated with different geological structures.

-

Fig. 20: (A) Displays the 3D distribution of density variations, highlighting the high-density regions within the inverted gravity model. (B) Shows the low-density structures in the model, which may correspond to sedimentary basins or less dense rock formations. (C) Represents the isosurfaces of density, visualizing density contrasts in the subsurface.

-