Abstract

Total hip arthroplasty can cause moderate and severe pain that can have a profound impact during postoperative rehabilitation. Regional nerve block is recommended for anesthesia and analgesia during hip surgery. In particular, the iliac fascia space block of the inguinal ligament is a widely used technique in clinical practice that can block the femoral nerve trunk, obturator nerve trunk, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve simultaneously. This study aimed to compare the effect of supra-inguinal fascia iliaca compartment block (S-FICB) to a combination of pericapsular nerve group block (PNGB) and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block (LFCNB) on block range and analgesia as well as motor function of patients with total hip arthroplasty. Sixty patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty through posterolateral approach were randomly divided into two groups with 30 patients each. After complete awakening from general anesthesia, patients received ultrasound-guided S-FICB with 40 mL 0.4% ropivacaine (group S) or 20 mL 0.4% ropivacaine PNGB combined with 3 mL 0.4% ropivacaine LFCNB (PH group). We used the Numerical Rating Scale and cumulative dosage of sufentanil to grade pain during the first 48 h. Quadriceps femoris muscle and adductor muscle strength, range of sensory block, length of stay, and complications were also recorded. No significant differences were found in analgesic indicators of both groups (P>0.05). The Numerical Rating Scale scores of resting pain at each time point after the blockage were significantly lower than those before the blockage (P<0.05). However, the PH group had significantly less incidence of analgesia sensation in the anterior and medial side of the thigh (P < 0.05), and less incidence of quadriceps and adductor weakness (P<0.05) at 1 h and 6 h after the blockage compared to that in group S. Compared to S-FICB, the combination of PNGB and LFCNB provided equivalent analgesic effect and significantly lowered the risk of numbness and muscle weakness of the thigh, which is more conducive to early postoperative exercise and rehabilitation .This combination can be used as a new option in multimodal analgesia after total hip arthroplasty.

Trial registration: Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (no. ChiCTR2200055963, date of registration 29/01/2022).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) reduces long-term complications in patients with severe hip joint diseases1. However, it can cause moderate and severe pain that can have a profound impact during postoperative rehabilitation2. Regional nerve block is recommended for anesthesia and analgesia during hip surgery3. In particular, the iliac fascia space block of the inguinal ligament is a widely used technique in clinical practice that can block the femoral nerve trunk, obturator nerve trunk, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) simultaneously4. Since it blocks the femoral nerve trunk, it can cause quadriceps femoris weakness, which may affect the functional exercise ability of patients5. Philip et al. (2018) proposed that hip pericapsular nerve group block (PNGB), can target and block the hip sensory branch of femoral nerve, hip sensory branch of obturator nerve, and variant accessory obturator nerve between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and iliopubic eminence6. Since the pain resulting from a lateral thigh incision is due to the LFCN7, it is speculated that PNGB combined with lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block (LFCNB) is more suitable for postoperative analgesia in association with THA.

This study aimed to compare the advantages and disadvantages of postoperative pain relief and early sensory and motor ability between the different blocks to provide basis for better postoperative analgesia in THA.

Methods

General information

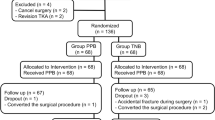

This study was approved by the China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University Institutional Review Committee (20220118007) and was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200055963)on 29/01/2022. Sixty patients who underwent elective THA under general anesthesia were included in this study at China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin from31/01/2022 to 30/6/2022. The inclusion criteria comprised patients who were American Society of Anesthesiologists grades I–III aged 18–90 years old with body mass index (BMI) of 18–28 kg/m2 and used patient-controlled intravenous analgesia after surgery. The exclusion criteria consists of those with allergies to local anesthetics, general anesthetics, and disinfectants; infection of puncture site; severe systemic diseases including respiratory failure, cardiac insufficiency, coagulation disorder, and liver and kidney insufficiency; complicated central nervous system diseases; language dysfunction, inability to cooperate with the evaluation of a digital analog pain score [Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)] and postoperative follow-up; and chronic motor dysfunction of the lower limbs. Patients voluntarily participated and provided written informed consent.

Randomization and allocation

Randomization will be in 1:1ratio without strategy using a numerical sequence derived from a random number table, which allocated participants to one of the two groups. Computer-generated randomized group information will be numbered, sealed in an opaque envelope by independent assistants not involved in other parts of the study, and used sequentially. Allocation will be revealed by the anesthetist responding regional block after the Ramsey scale rated as 2 which is cooperative, oriented, and tranquil. The senior anesthetist experienced in these techniques will do the intervention for all participants to rule out the confounding of regional skill. Other investigators except for him, surgeon staff, and patients will be kept blinded to group allocation.

Procedures

Sixty patients were divided into S and PH groups (defined below) with 30 cases in each group (see Additional file 1). After entering the operating room, venous access was obtained, and vital signs were monitored. A slow intravenous injection of midazolam 0.03 mg/kg, propofol 2 mg/kg (an appropriate compound, etomidate, for older patients), cis-atracurium 0.2 mg/kg, and sufentanil 0.3 µg/kg was administered to complete the induction of anesthesia, and mechanical ventilation was performed after endotracheal intubation. Propofol and remifentanil were administered via pump infusion for anesthesia maintenance, and bispectral index value was maintained at 40–60. After extubation, the patient was transferred to an anesthesia recovery room. NRS pain scores at rest were evaluated when the patient fully recovered to a quiet and cooperative state. Subsequently, nerve block was performed by the same experienced anesthesiologist according to the results of randomization.

In the group S, the 5–12-MHz high-frequency linear array probe was placed at the inguinal ligament in the outer 1/3 of the line between pubic tubercle and ASIS so that the probe was at a 40° from the sagittal plane. The probe was adjusted to completely display the “bow tie sign,” composed of the sartorius muscle, internal oblique muscle, iliac fascia, iliopsoas muscle, and deep iliac circumflex artery superficial to the iliac fascia. After 2% of lidocaine local anesthesia took effect, the needle was inserted from the caudal to the cephalic side by an in-plane puncture technique that reached the iliac fascia space between the deep iliac circumflex artery and iliopsoas muscle, and 40 mL of 0.4% ropivacaine was injected after no blood was withdrawn.

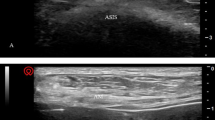

Meanwhile, patients in the PH group were treated with PNGB combined with LFCN block. After local skin disinfection, the 2–5 MHz low frequency convex array ultrasound probe was placed horizontally at the anterior inferior iliac spine and the probe was rotated counterclockwise about 45° to show the femoral artery, iliopsoas muscle, pubic muscle, pubic branch, and iliopubic eminence. After 2% of lidocaine local anesthesia took effect, the needle was inserted from outside to inside using the in-plane method. Once the needle tip reached the myofascial space between psoas major tendon and pubic branch and no blood was withdrawn, 20 mL of 0.4% ropivacaine was slowly injected for PNGB (Fig. 1). Then, the 5–12 MHz high-frequency linear array probe was removed and placed 2 cm below the ASIS to identify the sartorius and tensor fasciae latae muscles, and the LFCN was identified in the fat pad between them and traced to the proximal end of the nerve as far as possible. After administering the same local anesthesia, 3 mL of 0.4% ropivacaine was injected to block the LFCN.

Patients in both groups were attached to patient-controlled intravenous analgesia pumps before leaving the operating room after surgery. The pumps consisted of 150 µg sufentanil and 10 mg tropisetron mixed with 0.9% sodium chloride injection to 100 mL. The analgesic pump was set to a continuous infusion volume of 2 mL/h, increased by 0.5 mL/time with a locking time of 15 min. When the resting NRS score was ≥ 4, the patients were instructed to add analgesia through the intravenous analgesic pump. If relief is not achieved after 15 min, a remedial analgesia is given using non-steroidal drugs, 50 mg tramadol, and 3 mg oxycodone until the resting NRS score became ≤ 2.

The primary outcome indicators

-

(1)

Evaluation of analgesic effect: NRS pain score at rest before administering nerve block, NRS pain score at rest and exercise at 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after administering nerve block.

-

(2)

Evaluation of block effect: Muscle strength was evaluated through the incidence of myasthenia (muscle strength ≤ grade 2) at 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after the block was evaluated using the Lovett grading method8. The patient was instructed to undergo straight leg raise of the lower limb on the operated side at a certain resistance over time, and the quadriceps muscle strength was graded. Moreover, patient was then instructed to adduct lower limb on the operated side at a certain resistance over time, and the adductor muscle strength was graded.

The secondary outcome indicators

-

(1)

Evaluation of analgesic effect: The patient controlled the number of supplements, cumulative dosage of sufentanil, analgesic satisfaction score (range 0–10), and additional analgesic dosage within 24 h and 24–48 h after block.

-

(2)

Evaluation of block effect: The cold stimulation method was used to evaluate the sensory block range 30 min after the block. Compared with the healthy limb, the sensory hypoesthesia of the anterior, medial, and lateral skin of the thigh were recorded.

-

(3)

Postoperative length of stay.

-

(4)

Occurrence of adverse reactions such as infection, hematoma, nausea and vomiting, and dizziness at the puncture site.

Statement

The authors confirm that all methods are carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysis

Previous reports regard a mean difference of 2.0 in pain scores between the groups will be considered clinically significant9 .To show such a difference, a calculated sample size of 30 patients per group will be required to provide us with a statistical power of 0.8 and a type 1 error of 0.05 for a 2-tailed test.

SPSS 21.0 was used for statistical analysis. The measurement data were described by Mean ± standard deviation (\(\left( {\bar{x} \pm S} \right)\)),and they were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test.Independent samples t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare data conforming a normal and nonparametric distribution, respectively. NRS scores during resting pain and exercise pain at different time points were compared using the generalized estimation equation. Classification and counting data were expressed as the number of cases (percentage), and the comparison between groups was assessed using χ2 test. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Comparison of general data

No patients in either group quit or were lost to follow-up. No statistical difference in sex ratio, age, BMI, and operation time between the two groups was found (P > 0.05, Table 1).

Primary results

Comparison of NRS scores of resting pain before and after block between the two groups

The generalized estimation equation showed no significant difference in NRS scores of resting pain among different groups and interaction between groups and time (P > 0.05), but there was a significant difference at different time points (P < 0.05). The comparison between the two groups at the same time point showed no significant difference in the NRS scores of resting pain before and after administering nerve block (P > 0.05). In Group PH, the NRS score of resting pain at 48 h after blockage was significantly lower than that at 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h after blockage. In Group S, the NRS scores of resting pain at 24 h and 48 h after blockage were significantly lower than that at 1 h, 6 h, and 12 h after block (P < 0.05, Table 2; Fig. 2).

Comparison of the NRS of motor pain at each time point after administering block between the two groups

No significant difference was found in the NRS scores of motor pain among different groups and interaction between groups and time (P > 0.05), but there was a significant difference in different time points (P < 0.05). Comparing the two groups at the same time point showed no significant difference in the NRS scores of motor pain at each time point before and after blockage (P > 0.05). In Group PH, the NRS scores during exercise pain at 48 h after block were significantly lower than those at 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h after blockage. Meanwhile, in Group S, NRS scores at 24 h and 48 h after blockage were significantly lower than those at 1 h, 6 h, and 12 h after blockage (P < 0.05, Table 3; Fig. 3).

Comparison of muscle strength at each time point after administering nerve blocks in the two groups

Compared with Group PH, Group S had a higher rate of quadriceps weakness at 1 h and 6 h after blockage, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05, Table 4). The rate of adductor muscle weakness in Group S was higher than that in Group PH at 1 h and 6 h after blockage (P < 0.05, Table 5).

Secondary results

Comparison of postoperative analgesic drugs and analgesic satisfaction between the two groups

No remedial analgesia was used in either group. No significant difference in the number of additional analgesic pumps and the dosage of sufentanil required within 24 h and 24–48 h was found between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 6). The postoperative pain satisfaction of the two groups was 9 (8, 9) in Group PH and 9 (8, 9) in Group S, with no significant difference (Z=-0.848, P = 0.397). The satisfaction of 48-hour analgesia was 9 (9, 10) in Group PH and 9 (9, 9) in Group S, with no significant difference (Z=-0.591, P = 0.554).

Comparison of skin sensory block between the two groups 30 min after blockage

Thirty minutes after administering nerve block, the anterior thigh sensation of patients in Group PH decreased in 11 cases (36.7%), which was significantly lower than those in Group S (100%; χ2 = 27.8, P < 0.01). There were nine cases (30.0%) with hypoesthesia in the medial thigh in Group PH, which was significantly lower than that in Group S (73.3%; χ2 = 11.279, P < 0.01). There were 30 cases (100%) in Group PH and 29 cases (96.7%) in Group S, with no significant difference (χ2 = 0, P = 1.0).

Comparison of postoperative hospitalization time and adverse reactions

The postoperative hospital stay was 7.00 (4.75, 8.25) days in Group PH and 6.00 (4.00, 7.25) days in Group S, with no significant difference (Z=-1. 029, P = 0. 303). Postoperative nausea and vomiting occurred in four cases (13.3%) in Group PH and six cases (20.0%) in Group S; while postoperative dizziness occurred in four cases (13.3%) in Group PH and four cases (13.3%) in Group S. No puncture site infection and hematoma was present in the patients of both groups, and had no significant difference for adverse events (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The innervation of the hip joint is complex. Its sensory fibers are mainly distributed in the anterior part of the hip joint capsule, and the sensory branch of the hip joint of the femoral nerve and accessory obturator nerve, play important roles10,11. Given the posterior part of hip capsule is innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and articular branch of the sciatic nerve12, intravenous analgesia was applied based on nerve blocks in both groups. Compared with supra-inguinal fascia iliaca compartment block (S-FICB), PNGB combined with LFCNB were associated with similar analgesic scores, opioid use, and analgesic satisfaction after THA at each time point. This suggests that the analgesic effect of PNGB combined with LFCNB was similar with S-FICB, which is consistent with case reports suggesting that the combined scheme could be used for anesthesia in hip arthroscopy7.

In terms of exercise, PNGB has less of an effect on lower limb muscle strength than that of S-FICB, which is beneficial to the preservation and recovery of patients’ active motor function after surgery. However, there is still a 16.7% probability of quadriceps weakness 1 h after blockage. A similar result explained liquid medicine may directly infiltrate the femoral nerve through the psoas major muscle, or that the puncture needle is closer to the pubic muscle, which spreads the liquid medicine to the main trunk of the femoral nerve through the gap between the pubic muscle and the psoas major muscle, hence resulting in a motor block13. To avoid this, the needle body has to be rotated to penetrate the needle tip into the psoas major fascia and that the liquid medicine can diffuse in the plane between the psoas major tendon and the iliopubic eminence13.

Given that the sensory distribution of the obturator nerve in the inner thigh is quite different or even missing, a sensory block cannot be used as a sign of successful obturator nerve block; the only reliable indication is thigh adductor muscle weakness14. Therefore, in this study, adductor myasthenia was used to evaluate the effect of S-FICB on the obturator nerve. According to the recommended dose of KRIS Vermeylen15, 40 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine was used. The probability of adductor myasthenia at 1 h was 70% and that at 6 h was 53.3%, which was higher than that in the PNGB combined with LFCN group. At the same time, the block rate of the obturator nerve by this method did not reach 100%, which was consistent with the literature16,17, As S-FICB has obvious influence on the muscle strength of quadriceps femoris and adductor muscle within 24 h, it is necessary to pay attention to the effect of S-FICB on active functional exercise ability in the early stage of single analgesia or continuous block analgesia as it may lead to an increased risk of falling during autonomous activities, consistent with previous studies5. In terms of sensory block range, the present study showed that PNGB combined with LFCNB significantly reduced the sensory block of the anterior and medial thigh skin, indicating that PNGB can target the sensory branches of the hip joint, but has negligible effect on the nerve trunk.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center study with a limited number of cases. We acknowledged the limitations of not making adjustments for dropouts. And the anesthesiologist performing the block was unblinded. The accompanying type II error may has a potential impact on secondary outcomes such as postoperative hospitalization time and adverse reactions. Future studies should recruit larger sample size, and the results of the present study must be verified by a multicenter study. Second, the qualitative evaluation of muscle strength was not sufficiently accurate. This method was subjective and might have some influence on the evaluation results of muscle strength; thus, it could be quantitatively evaluated using a handheld muscle strength meter18. Third, no placebo control group was included. Anatomical studies have reported that 10 mL of local anesthetic can also spread between the anterior capsule of the hip joint and the iliopsoas muscle19. A follow-up test should include a combined group of low-volume PNGB, LFCNB, and placebo control group without nerve block to determine the best dose of local anesthetics. Finally, this study did not conduct a follow-up test for the patients after 48 h, including the Harris score at one month20. Joint function, activity recovery, and chronic pain should be evaluated three months after surgery.

Conclusions

When combined with LFCNB, PNGB has the same postoperative analgesic effect as iliac fascia space block on the inguinal ligament. It can reduce the range of skin hypoesthesia and preserve the motor function of patients, which is more conducive to early postoperative exercise and rehabilitation and can be used as a new option in multimodal analgesia after THA.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, H. Y. Clinical effect of THA in the treatment of femoral neck fracture in the elderly. Chin. J. Mod. Drug Appl. 14, 96–98 (2020).

Skinner, H. B. & Shintani, E. Y. Results of a multimodal analgesic trial involving patients with total hip or total knee arthroplasty. Am. J. Orthop. (Belle Mead NJ). 33, 85–92 (2004).

Yue, Z. & Ni, X. H. Application of ultrasound combined with nerve stimulator for lower limb nerve block in elderly patients with hip replacement. Xinjiang Med. J. 49, 885–888 (2009).

Neubrand, T. L., Roswell, K., Deakyne, S., Kocher, K. & Wathen, J. Fascia Iliaca compartment nerve block versus systemic pain control for acute femur fractures in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 30, 469–473 (2014).

Bober, K., Kadado, A., Charters, M., Ayoola, A. & North, T. Pain control after THA: a randomized controlled trial determining efficacy of fascia Iliaca compartment blocks in the immediate postoperative period. J. Arthroplasty. 35, S241–S245 (2020).

Girón-Arango, L., Peng, P. W. H., Chin, K. J., Brull, R. & Perlas, A. Pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block for hip fracture. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 43, 859–863 (2018).

Roy, R., Agarwal, G., Pradhan, C. & Kuanar, D. Total postoperative analgesia for hip surgeries, PENG block with LFCN block. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 44, 684 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Neuronavigation-guided corticospinal tract mapping in brainstem tumor surgery: better preservation of motor function. World Neurosurg. 116, e291–e297 (2018).

Choi, Y. S., Park, K. K., Lee, B., Nam, W. S. & Kim, D. H. Pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block versus supra-Inguinal fascia Iliaca compartment block for total hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. J. Pers. Med. 12, 408 (2022).

Gerhardt, M. et al. Characterisation and classification of the neural anatomy in the human hip joint. Hip Int. 22, 75–81 (2012).

Bhatia, A., Hoydonckx, Y., Peng, P. & Cohen, S. P. Radiofrequency procedures to relieve chronic hip pain: an evidence-based narrative review. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 43, 72–83 (2018).

Birnbaum, K., Prescher, A., Hessler, S. & Heller, K. D. The sensory innervation of the hip joint - an anatomical study. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 19, 371–375 (1997).

Giron Arango, L. & Peng, P. Reply to Dr Yu et al. Inadvertent quadriceps weakness following the pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 44, 613–614 (2019).

Bouaziz, H. et al. An evaluation of the cutaneous distribution after obturator nerve block. Anesth. Analg. 94, 445–449 (2002).

Vermeylen, K. et al. The effect of the volume of supra-inguinal injected solution on the spread of the injectate under the fascia iliaca: a preliminary study. J. Anesth. 32, 908–913 (2018).

Marhofer, P., Nasel, C., Sitzwohl, C. & Kapral, S. Magnetic resonance imaging of the distribution of local anesthetic during the three-in-one block. Anesth. Analg. 90, 119–124 (2000).

Swenson, J. D. et al. Local anesthetic injection deep to the fascia Iliaca at the level of the inguinal ligament: the pattern of distribution and effects on the obturator nerve. J. Clin. Anesth. 27, 652–657 (2015).

Welling, W. et al. Monitoring hamstring and quadriceps strength using handheld dynamometry in patients after ACL reconstruction: a prospective longitudinal study. J. Orthop. 2025, 59128–59136 (2025).

Tran, J., Agur, A. & Peng, P. Is pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block a true pericapsular block? Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 44, 257 (2019).

Ibrahim, S. S. et al. Evaluation of some treatment options inlate and neglected hip fractures using the modified Harris hip score. Open. J. Orthop. 14, 259–269 (2024).

Acknowledgements

My deepest gratitude goes first to Professor Zhao Guoqing, my supervisor during the postgraduate period, for his constant encouragement and guidance. Second, I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Li Longyun, who gave me a lot of support in my experiment. Last my thanks would go to my beloved family for their loving considerations and great confidence in me all through these years.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT was responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Roles/Writing - original draft. KL and QL was responsible for Project administration, Writing - review & editing, Resources, and Funding acquisition.YY was responsible for Data curation and Software. ZH was responsible for Validation and Visualization. WL was responsible for Investigation and Formal analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University Institutional Review Committee (20220118007) and was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200055963). Patients voluntarily participated and provided written informed consent.

Ethical statement

The participants were not compensated for their involvement for their involvement. No additional fees were incurred.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, Y., Lu, Q., Yuan, Y. et al. The effect of pericapsular nerve group block and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block on postoperative recovery after hip arthroplasty. Sci Rep 15, 19913 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04699-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04699-6