Abstract

This work explores the time-space fractional soliton neuron model (TSFSNM), a framework that accounts for the inherent time-space nonlinearity prevalent across various fields, including mathematical physics, nonlinear dynamics, and engineering disciplines such as neurosciences, biosciences, fluid mechanics, plasma physics, and geochemistry. The innovation of this paper lies in introducing and employing advanced fractional modeling techniques, namely the modified Sardar sub-equation (MSSE) method and the improved F-expansion method. We construct explicit analytical solutions, offering insights into the solitary sound pulses that represent signals passing through the cell membrane (CM). These pulses are modeled as solitons, capturing the localized dynamics of neuronal communication. Furthermore, bifurcation and sensitivity analysis provide a deeper understanding of the influence of fractional-order parameters on the system’s behavior. The findings emphasize the significance of fractional soliton models in describing complex wave phenomena in diverse scientific and engineering contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

TSFSNM captures the nonlinear and confined nature of neural activity by accurately modeling the propagation of signals as solitary sound pulses (solitons) across the cell membrane1,2,3,4. Memory effects and inherited characteristics are taken into account by fractional derivatives, which are crucial in biological systems like the brain. This makes it possible to depict long-term interdependence in signal transmission more realistically. The model is especially important in domains like fluid mechanics, plasma physics, neuroscience, and biosciences because it offers a precise and adaptable framework for predicting and interpreting intricate wave occurrences5,6,7,8,9. For instance, TSFSNMs are used to accurately identify the heat flow, wave propagation processes, mathematical physics, neural network dynamics, and action potential propagation. A lot of presentations in applied science and mathematical physics are made mathematically as TSFNLPs. Despite having historic roots, they have advanced significantly in the last fifty years. Numerous issues posed by TSFNLPs have drawn the attention of mathematicians, scientists, and engineers10,11. Their vital significance in mathematical physics and applied science is the primary driving force behind this study.

Numerous analytical and numerical methods have been developed to solve such complex situations. The bifurcation analysis technique12, Hirota bilinear method13, the variational iteration method14, the exponential rational function approach15, the inverse scattering method16, the modified Jacobi elliptic expansion method17, and numerous others18,19,20 are among these varied approaches. The importance of exact solutions is found in their capacity to offer an accurate, trustworthy, and perceptive understanding of nonlinear systems in a variety of engineering and scientific fields21,22. They allow precise models of physical phenomena including solitons, wave dynamics, and bifurcations and are useful tools for model verification, sensitivity analysis, and additional research.

The convergence of fractional calculus, soliton theory, and classical neuron models led to the creation of the TSFSNM23. A strong foundation for simulating intricate neuronal dynamics has been made available by this interdisciplinary approach, which reflects the complex spatial and temporal interactions present in neural models. In this article, our main focus is to examine the TSFSNM equation24:

here, \(\beta\) represents the order of fractional derivative, x represents position along the nerve axon, t represents time, a represents the nerve membrane’s (NM) sound velocity (SV), c and b characterize the phase transition and nonlinearity of the NM’s elastic constants, d represents the frequency dependence of the membrane’s SV, and U is the membrane density (MD) fluctuation caused by the action potential (AP). The parameters a, b, and c are the thermodynamic assets of the NM and so cannot be freely altered.

In this study, the soliton solutions of the TSFSNM have been extracted using the improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion approach and the modified Sardar sub-equation (MSSE) method. The process of discovering new solutions, such as bright solitons, single solitons, combo, rational solutions, singular periodic wave solutions, exponential solutions, and hyperbolic solutions, has been thoroughly mathematically analyzed. We also examine how these fractional characteristics affect the resulting wave profiles’ coherence and stability, which may have important ramifications for comprehending brain signaling in both healthy and pathological conditions. In order to visualize the nature of some of the discovered solutions, contour projection plots in both 2D and 3D have also been provided. Additionally, the aforementioned model’s bifurcation and sensitivity analysis is an analysis that is crucial for dynamical systems. Furthermore, the study offers possible uses for the soliton solutions that were obtained in a number of domains, such as applied mathematics, engineering, and neuroscience.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: In “Fractional derivative (FD) and the Methodologies”, we provided the basic features of selected derivative as well as methodologies. “Extaction of exact solutions” signifies how to apply the MSSE method and the improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion to Eq. (1) and get optical Dromions soliton solutions. In “Analysis of bifurcation” we present the bifurcation and sensitivity analysis of the TSFSNM. In “Results and discussion” the description of graphs as well as effect of fractional parameters are visualized. Finally, conclusions are presented in “Conclusion”.

Fractional derivative (FD) and the methodologies

In order to simulate processes with memory and hereditary features, a FD extends the idea of integer-order derivatives to non-integer orders. Fractional derivatives, as opposed to integer-order derivatives, are essential for simulating intricate and real-world systems because they take into account a function’s whole historical behavior.

We will provide the definition of a FD25:

The definition (2) mentioned above adheres to the following properties:

We look at a specific kind of fractional equation that is not linear.

The wave transformation is described as:

here, the amplitude is shown by \(V(\prod )\). Eq. (5) is transformed into a nonlinear ordinary differential equation (ODE) in accordance with the strategy:

The MSSE method

In this section, we describe the steps involved in MSSE method. Following steps are involved:

Ist step. Assume the following is the trial solution of Eq. (6) to obtain different results:

where \(\varpi _i (i = 0, 1, 2,\cdots ,n)\) are the real coefficients. The function \(S(\prod )\) from Eq. (7) is satisfied by the Ricati equation:

where \(\upsilon _0,~\upsilon _1,~\upsilon _2\) are constants. Additionally, typical solutions to Eq. (8) using \(\tau\), an arbitrary constant, are listed below:

- (i):

-

If \(\upsilon _0\) = 0, \(\upsilon _1 > 0\) and \(\upsilon _2 \ne\) 0, then

$$\begin{aligned} S_1(\prod )= \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \text {sech}\left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(9)$$\begin{aligned} S_2(\prod )=\pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \text {csch}\left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(10) - (ii):

-

For constants \(g_1\), \(g_2\), \(\upsilon _0\)=0, \(\upsilon _1>\)0 and \(\upsilon _2 = 4 * g_1 * g_2\), then

$$\begin{aligned} S_3(\prod )= \pm \frac{4 g_1 \sqrt{\upsilon _1}}{\left( 4 g_1^2-\upsilon _2\right) \sinh \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) +\left( 4 g_1^2-\upsilon _2\right) \cosh \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) }. \end{aligned}$$(11) - (iii):

-

For constants \(r_1\), \(r_2\), \(\upsilon _0\)=\(\frac{\upsilon _1^2}{4 \upsilon _2}\)0, \(\upsilon _1<\)0 and \(\upsilon _2 > 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} S_4(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \tanh \left( \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2}} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(12)$$\begin{aligned} S_5(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \coth \left( \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2}} (\prod +\tau )\right) .\end{aligned}$$(13)$$\begin{aligned} S_6(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \left( \tanh \left( \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2}} (\prod +\tau )\right) +i \text {sech}\left( \sqrt{-2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) \right) .\end{aligned}$$(14)$$\begin{aligned} S_7(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{8 \upsilon _2}} \left( \tanh \left( \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{8}} (\prod +\tau )\right) +i \text {coth}\left( \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{8}} (\prod +\tau )\right) \right) .\end{aligned}$$(15)$$\begin{aligned} S_8(\prod )= & \pm \frac{\sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \left( \sqrt{r_1^2+r_2^2}-r_1 \cosh \left( \sqrt{-2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) \right) }{r_1 \sinh \left( \sqrt{-2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) +r_2}.\end{aligned}$$(16)$$\begin{aligned} S_9(\prod )= & \pm \frac{\sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \cosh \left( \sqrt{-2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) }{\sinh \left( \sqrt{-2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) +s}. \end{aligned}$$(17) - (iv):

-

If \(\upsilon _0\)= 0, \(\upsilon _1 <0\) and \(\upsilon _2 \ne\) 0, then

$$\begin{aligned} S_{10}(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sec \left( \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(18)$$\begin{aligned} S_{11}(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \csc \left( \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(19) - (v):

-

If \(\upsilon _0\)= \(\frac{\upsilon _1^2}{4 \upsilon _2}\), \(\upsilon _1>\)0 and \(\upsilon _2 > 0\) 0 and \(r_1^2 -r_2^2>0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} S_{12}(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \tan \left( \sqrt{\frac{\upsilon _1}{2}} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(20)$$\begin{aligned} S_{13}(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \cot \left( \sqrt{\frac{\upsilon _1}{2}} (\prod +\tau )\right) . \end{aligned}$$(21)$$\begin{aligned} S_{14}(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \left( \tan \left( \sqrt{2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) -\sec \left( \sqrt{2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) \right) .\end{aligned}$$(22)$$\begin{aligned} S_{15}(\prod )= & \pm \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{8 \upsilon _2}} \left( \tan \left( \sqrt{\frac{\upsilon _1}{8}} (\prod +\tau )\right) -\cot \left( \sqrt{\frac{\upsilon _1}{8}} (\prod +\tau )\right) \right) .\end{aligned}$$(23)$$\begin{aligned} S_{16}(\prod )= & \pm \frac{\sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \left( \sqrt{r_1^2-r_2^2}-r_1 \cos \left( \sqrt{2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) \right) }{r_1 \sin \left( \sqrt{2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) +r_2}.\end{aligned}$$(24)$$\begin{aligned} S_{17}(\prod )= & \pm \frac{\sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{2 \upsilon _2}} \cos \left( \sqrt{2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) }{\sin \left( \sqrt{2 \upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )\right) -1}. \end{aligned}$$(25) - (vi):

-

If \(\upsilon _0\)=0, \(\upsilon _1 >0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} S_{18}(\prod )= & \pm \frac{4 \upsilon _1 e^{\sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )}}{e^{2 \sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )}-4 \upsilon _1 \upsilon _2}. \end{aligned}$$(26)$$\begin{aligned} S_{19}(\prod )= & \pm \frac{4 \upsilon _1 e^{\sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )}}{1-4 \upsilon _1 \upsilon _2 e^{2 \sqrt{\upsilon _1} (\prod +\tau )}}. \end{aligned}$$(27)

2nd step: Using the balance theory on Eq. (6), we determine the value of N.

3rd step: Equations (7) and (8) are switched into Eq. (6), and all of the coefficients of power of \(S(\prod )\) are set to zero. In order to obtain the values of the unknowns \(\gamma _0,~\gamma _i\), and \(\vartheta\), which will be used to derive the solution of Eq. (4), we finally solve these equations using the computation program.

The improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion scheme

The improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion method is a versatile, efficient, and robust analytical tool that significantly enhances the ability to solve nonlinear partial differential equations. Its wide range of applications and ability to produce a variety of precise solutions make it indispensable for furthering research in the practical and mathematical sciences.

Ist step: Assume that Eq. (6) has the following trial solution:

where \(\mu _i\) and \(\lambda _i\) are not both zero at the same time. Where \(v = v(\prod )\) assures:

where \(\mathscr {L}\) refers as a constant. The following is the outcome of Eq. (6):

Case-I: If \(\mathscr {L} <0\), then

Case-II: If \(\mathscr {L} >0\), then

Case-III: If \(\mathscr {L}=0\),

2nd step: We use the balance theory on Eq. (7) to retrieve the value of N.

3rd step: The overdetermined system of nonlinear algebraic equations is obtained by substituting Eqs. (7) and (8) in Eq. (6) and setting all coefficients of power of \(\mathscr {F}(\prod )\) to zero. The values of the unknowns \(~ \mu _ i,~ \lambda _i\) m are obtained by solving these equations and will be used to build the solution of Eq. (6).

Extaction of exact solutions

The answers to the TSFSNM equation are essential for expanding our knowledge of the brain and creating useful applications in fields like artificial intelligence and medicine. These models facilitate the resolution of intricate problems in neuroscience and open the door for creative solutions in a number of domains by offering a more realistic depiction of brain processes.

According to the Eq. (35), Eq. (1) can be represented as:

The MSSE method

We have obtained \(N=1\) by equating the nonlinear terms and highest-order linear found in Eq. (36). Consequently, the following is the structure of the solution for Eq. (36):

When Eq. (37) are inserted into Eq. (36), an algebraic system of equations is produced. We find the following set of solutions by solving them:

\({\textbf {Family-I:}}\)

Putting these solutions into Eq. (37), we derived the following solutions:

-

If \(\upsilon _0\)=0, \(\upsilon _1 > 0\) and \(\upsilon _2 \ne 0\), we secure bright and singular solitons

$$\begin{aligned} U_{1}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \text {sech}\left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c}}.\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(39)$$\begin{aligned} U_{2}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \text {csch}\left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c}}.\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(40) -

For constants \(r_1\), \(r_2\), \(\upsilon _0\)=0, \(\upsilon _1>\)0 and \(\upsilon _2 = 4 \times g_1 \times g_2\), then combo solitons as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{3}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{4 \sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} g_1 \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega }{\sqrt{c} \left( 4 g_1^2-\upsilon _2\right) \left( \sinh \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) +\cosh \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) \right) }.\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(41) -

For constants \(r_1\), \(r_2\), \(\upsilon _0\)=\(\frac{\upsilon _1^2}{4 \upsilon _2}\), \(\upsilon _1 <\)0 and \(\upsilon _2 > 0\), we find dark and other singular soliton solutions as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{4}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \tanh \left( \frac{\sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{\sqrt{2}}\right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(42)$$\begin{aligned} U_{5}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \coth \left( \frac{\sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{\sqrt{2}}\right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(43)The combo solitons as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{6}(x,t)= & bigg[\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \left( \tanh \left( \frac{\sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{\sqrt{2}}\right) +i \text {sech}\left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(44)$$\begin{aligned} U_{7}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \left( \tanh \left( \frac{\sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{2 \sqrt{2}}\right) +\coth \left( \frac{\sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{2 \sqrt{2}}\right) \right) }{2 \sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(45)$$\begin{aligned} U_{8}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \left( \sqrt{r_1^2+r_2^2}-r_1 \cosh \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c} \left( r_1 \sinh \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) +\upsilon _2\right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(46)$$\begin{aligned} U_{9}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \cosh \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c} \left( \sinh \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) +i\right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(47) -

If \(\upsilon _0\)=0, \(\upsilon _1 <0\) and \(\upsilon _2 \ne\) 0, we achieve trigonometric function solutions as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{10}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \sec \left( \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(48)$$\begin{aligned} U_{11}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \csc \left( \sqrt{-\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(49) -

If \(\upsilon _0\)=\(\frac{\upsilon _1^2}{4 \upsilon _2}\), \(\upsilon _1>\)0 and \(\upsilon _2 > 0\) and \(r_1^2 -r_2^2>0\), then trigonometric function solutions as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{12}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \tan \left( \frac{\sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{\sqrt{2}}\right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(50)$$\begin{aligned} U_{13}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \cot \left( \frac{\sqrt{v_1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{\sqrt{2}}\right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(51)The mixed trigonometric function solutions as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{14}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \left( \tan \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) -\sec \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(52)$$\begin{aligned} U_{15}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \left( \tan \left( \frac{\sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{2 \sqrt{2}}\right) -\cot \left( \frac{\sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) }{2 \sqrt{2}}\right) \right) }{2 \sqrt{c}}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(53)$$\begin{aligned} U_{16}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \left( \sqrt{r_1^2-r_2^2}-r_1 \cos \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c} \left( r_1 \sin \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) +r_2\right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(54)$$\begin{aligned} U_{17}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\frac{\upsilon _1}{\upsilon _2}} \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \cos \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c} \left( \sin \left( \sqrt{2} \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) -1\right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(55) -

If \(\upsilon _0\)=0, and \(\upsilon _1>0\), then exponential solution as:

$$\begin{aligned} U_{18}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{4 \sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \upsilon _1 \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \exp \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c} \left( \exp \left( 2 \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) -4 \upsilon _1 \upsilon _2\right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(56)$$\begin{aligned} U_{19}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{4 \sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \upsilon _1 \sqrt{\upsilon _2} \omega \exp \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) }{\sqrt{c} \left( 1-4 \upsilon _1 \upsilon _2 \exp \left( \sqrt{\upsilon _1} \left( \frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{\omega ^2 \left( a^2-d \upsilon _1 \omega ^2\right) }}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}+\tau +x \omega \right) \right) \right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(57)

Implementation of the improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion method

Bases on the improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion method, from Eq. (69)

We obtain solution sets by combining Eqs. (58) and (29) in Eq. (36): Family-I:

-

When \(\mathscr {L} < 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} U_{1}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{12 \sqrt{6} d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2 \text {sech}^2\left( \sqrt{-\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }{\sqrt{6} b-12 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\mathscr {L}} \omega \tanh \left( \sqrt{-\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(59)$$\begin{aligned} U_{2}(x,t)= & \bigg [-\frac{12 \sqrt{6} d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2 \text {csch}^2\left( \sqrt{-\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }{\sqrt{6} b-12 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{-\mathscr {L}} \omega \coth \left( \sqrt{-\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(60) -

When \(\mathscr {L} > 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} U_{3}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{12 \sqrt{6} d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2 \sec ^2\left( \sqrt{\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }{12 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{\mathscr {L}} \omega \tan \left( \sqrt{q} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) +\sqrt{6} b}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(61)$$\begin{aligned} U_{4}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{12 \sqrt{6} d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2 \csc ^2\left( \sqrt{\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }{\sqrt{6} b-12 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{\mathscr {L}} \omega \cot \left( \sqrt{\mathscr {L}} \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(62) -

When \(\mathscr {L} = 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} U_{5}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{12 \sqrt{6} d \omega \left( \mathscr {L} \omega ^2 \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) ^2+1\right) }{\left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) \left( \sqrt{6} b \omega \left( x-\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{a^2+4 d \mathscr {L} \omega ^2}}{\Gamma (\beta +1)}\right) -12 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \right) }\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(63)Family-II:

$$\begin{aligned} {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \lambda _0=\frac{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \left( \sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }-\sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} m \omega \right) }{c},~\lambda _1=\frac{\sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \omega }{\sqrt{c}},~\mu _1=\frac{\sqrt{6} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( m^2+\mathscr {L} \right) }{\sqrt{c}},\\ ~b=-\sqrt{6} \left( \sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }+\sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} m \omega \right) ,~\eta =\frac{\sqrt{-\frac{d^2 m \omega ^3 \left( 4 m^2+9 \mathscr {L} \right) \left( -a^2 \sqrt{c}+\sqrt{c} d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) +3 \sqrt{d} m \omega \sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }\right) }{\sqrt{c}}}}{\sqrt{d^2 m \omega \left( 4 m^2+9 \mathscr {L} \right) }}. \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$ -

When \(\mathscr {L} < 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} U_{6}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \left( \frac{2 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( m^2+\mathscr {L} \right) }{m-\sqrt{-\mathscr {L} } \tanh \left( \prod \sqrt{-\mathscr {L} }\right) }+\sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }+2 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( m-\sqrt{-\mathscr {L} } \tanh \left( \prod \sqrt{-\mathscr {L} }\right) \right) +\left( -\sqrt{c}\right) \sqrt{d} m \omega \right) }{c}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(64)$$\begin{aligned} U_{7}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \left( \frac{2 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( m^2+\mathscr {L} \right) }{m-\sqrt{-\mathscr {L} } \coth \left( \prod \sqrt{-\mathscr {L} }\right) }+\sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }+2 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( m-\sqrt{-\mathscr {L} } \coth \left( \prod \sqrt{-\mathscr {L} }\right) \right) +\left( -\sqrt{c}\right) \sqrt{d} m \omega \right) }{c}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(65) -

When \(\mathscr {L} > 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} U_{8}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \left( \frac{\sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( 3 m^2+m \sqrt{\mathscr {L} } \tan \left( \prod \sqrt{\mathscr {L}}\right) +2 \mathscr {L} \right) }{m+\sqrt{\mathscr {L} } \tan \left( \prod \sqrt{\mathscr {L} }\right) }+\sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }+2 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{\mathscr {L} } \omega \tan \left( \prod \sqrt{\mathscr {L} }\right) \right) }{c}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(66)$$\begin{aligned} U_{9}(x,t)= & \bigg [\frac{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \left( \frac{\sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( 3 m^2+m \sqrt{\mathscr {L} } \cot \left( \prod \sqrt{q}\right) +2 \mathscr {L} \right) }{m+\sqrt{\mathscr {L} } \cot \left( \prod \sqrt{\mathscr {L} }\right) }+\sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }+2 \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \sqrt{\mathscr {L} } \omega \cot \left( \prod \sqrt{\mathscr {L} }\right) \right) }{c}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(67) -

When \(\mathscr {L} = 0\), then

$$\begin{aligned} U_{10}(x,t)=\bigg [\frac{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \left( \sqrt{c} \sqrt{d} \omega \left( 3 \prod ^2 m^2-3 \zeta m+2 \prod ^2 \mathscr {L} +2\right) +\prod (\prod m-1) \sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L} \right) }\right) }{c \prod (\prod m-1)}\bigg ]. \end{aligned}$$(68)Where \(\prod =x \omega +\frac{t^{\beta } \sqrt{-\frac{d^2 m \omega ^3 \left( 4 m^2+9 \mathscr {L}\right) \left( -a^2 \sqrt{c}+\sqrt{c} d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L}\right) +3 \sqrt{d} m \omega \sqrt{c d \omega ^2 \left( 9 m^2+8 \mathscr {L}\right) }\right) }{\sqrt{c}}}}{\Gamma (\beta +1) \sqrt{d^2 m \omega \left( 4 m^2+9 \mathscr {L}\right) }}\).

Analysis of bifurcation

This section provides a thorough analysis of stationary (equilibrium) points and bifurcation analysis26 for the dynamic system described in Eq. (36), including phase portraits. First, we must resolve the following system:

where, \(\mathscr {U}_{1}=\frac{\eta ^2-a^2\omega ^2}{d \omega ^4}\), \(\mathscr {U}_{2}=\frac{b \omega ^2}{2d \omega ^4}\) and \(\mathscr {U}_{3}=\frac{c \omega ^2}{3d \omega ^4}\). The Hamiltonian function is regarded as follows for this:

To determine the stationary points \(\mathcal {S}\mathcal {P}s\), assume the Eq. (69), as follow:

finding the solution of the above system for \(\mathscr {U}_{1}\), \(\mathscr {U}_{2}\) and \(\mathscr {U}_{3}\), we get

Also, the determinant of the Jacobian for the system (69) is given by:

We know that:

-

If \({\mathbb {J}}({\mathbb {N}}_{i})<0\), then \({\mathbb {N}}_{i}\) is known as a saddle point.

-

If \({\mathbb {J}}({\mathbb {N}}_{i})>0\), then \({\mathbb {N}}_{i}\) is known as a center point,

-

If \({\mathbb {J}}({\mathbb {N}}_{i})>0\) and \({\mathbb {T}}^2-4{\mathbb {J}}\ge 0\), the stationary points (\(\mathcal {S}\mathcal {P}s\)) \({\mathbb {N}}_{i}\) corresponds to node. It is unstable if \({\mathbb {T}}> 0\) and stable if \({\mathbb {T}}< 0\).

The possible scenarios for different \(\mathcal {S}\mathcal {P}s\) are as follows:

-

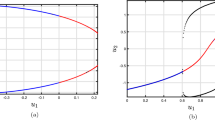

(i) When \(\mathscr {U}_{1}>0,~\mathscr {U}_{2}>0~ \& ~\mathscr {U}_{3}>0\). As illustrated in Fig. 1a, \({\mathbb {N}}_{0}\) = (0,0) is a stable degenerate node in this instance. For equation (1), the existence of periodic non-stationary periodic trajectories ensures that a closed-form solution will occur.

-

(ii) When \(\mathscr {U}_{1}>0,~\mathscr {U}_{2}<0~ \& ~\mathscr {U}_{3}<0\). In this case, \({\mathbb {N}}_\pm\) becomes an unstable saddle \(\mathcal {S}\mathcal {P}s\) and \({\mathbb {N}}_{0}\) becomes degenerate node, as shown in Fig. 1b.

-

(iii) When \(\mathscr {U}_{1}<0,~\mathscr {U}_{2}<0~ \& ~\mathscr {U}_{3}>0\). We observe that the \(\mathcal {S}\mathcal {P}\) \({\mathbb {N}}_{0}\)= (0, 0), is an unstable saddle point as illustrated in Fig. 1c. Closed form trajectories are not obtained in this case.

-

(iv) When \(\mathscr {U}_{1}<0,~\mathscr {U}_{2}<0~ \& ~\mathscr {U}_{3}<0\). As presented in Fig. 1d, \({\mathbb {N}}_{0}\) is unstable saddle point and \({\mathbb {N}}_{\pm }\) are stable center points.

-

(v) When \(\mathscr {U}_{1}>0,~\mathscr {U}_{2}>0~ \& ~\mathscr {U}_{3}<0\). We discover that the \(\mathcal {S}\mathcal {P}s\) \({\mathbb {N}}_{0}\) \({\mathbb {N}}_0 = (0, 0)\) is a center point that is stable as shown in Fig. 1e. Here closed form trajectories are obtained.

Chaotic structure

In this analysis, we checked the system’s chaotic paths by adding a perturbation term to the dynamical system. The study of chaotic behavior in dynamical systems is crucial for basic physics research, comprehending complexity, simulating real-world events, enhancing control and optimization, and fostering artistic expression. In this section, we have added an additional perturbed term to the system under consideration, \({\mathbb {C}}\cos ({\mathbb {D}}\), where \({\mathbb {C}}\) and \({\mathbb {D}}\) denote the amplitude and frequency, to create the perturbed form that follows:

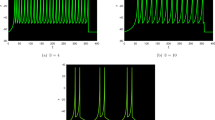

The phase diagram exhibits chaotic and quasi-periodic behaviors when the perturbed term is changed. The 2D–3D phase diagrams, and poincare map of the perturbed model (72) are exhibited in Figs. 2, 3 and 4 by taking different values of parameters \(\omega =.3,~\eta =.6,~a=.05,~b=-1.84,~c=.2,~d=2.09\). It is evident that the perturbed dynamical system described in Eq. (72) exhibit a quasi-periodic pattern.

The 2D–3D phase diagrams and poincare map in Fig. 2 show how the system behaves at particular frequencies (\({\mathbb {D}}=6.1\)) and amplitudes (\({\mathbb {C}}=2.9\)). The complex, symmetric pattern surrounding the origin in the phase diagram (2a,b) suggests quasi-periodic or periodic dynamics. The charts demonstrate that the system’s stable oscillations are influenced by the frequency and amplitude selected. Further information about this periodic behavior can be found in the poincare map (2c). The parameters are then increased to \({\mathbb {C}}=4.2\) and \({\mathbb {D}}=-3.2\). As seen in Fig. 3, this adjustment results in a slight perturbation in the system (72), which causes it to change into a complicated and captivating dynamic. The parameters are also increased to \({\mathbb {C}}=4.2\) and \({\mathbb {D}}=-0.93\). Furthermore, we increase the parameters to \({\mathbb {C}}=4.2\) and \({\mathbb {D}}=-0.93\). This modification results in a little disruption in the system (72), which causes it to change into a complicated chaotic dynamic, as shown in Fig. 4.

These results highlight how important the parameter \({\mathbb {D}}\) is in affecting the behavior of the system. The chaotic and periodic nature seen at various \({\mathbb {D}}\) values shows how the perturbed term \({\mathbb {C}}\cos ({\mathbb {D}}\)) has a significant effect on the system’s overall dynamics. This disruption highlights the fine balance and interaction of components in controlling the system’s evolution by causing a change from ordered periodic behavior to chaotic paths. To sum up, our numerical investigation of the phase diagrams offers important new information about the dynamics of the system and shows that the parameter \({\mathbb {D}}\) is highly sensitive to changes. Our comprehension of how external perturbations can significantly impact the overall behavior of dynamic systems is improved by the observable shift from periodicity to chaos, which illuminates the complex inter-dependencies within the system.

In order to differentiate between chaotic and regular behavior, the Lyapunov exponent is a helpful tool for understanding the stability and predictability of dynamical systems. Plotting the evolution of the exponents over time allows us to understand the dynamics of the system (69). The parameters \(\mathscr {U}_{1}= 2.5,~\mathscr {U}_{2}=1.3,~\mathscr {U}_{3}=0.2,~\mathscr {C}=3.7\), and \(\mathscr {D}=0.7\) will be used to determine the chaotic structure of the defined dynamical system as depicted in Fig. 5.

Detecting chaotic phenomena in the system (69) with the Lyapunov exponent.

Sensitivity analysis

In this section, we analyzed the sensitivity of the dynamical system using the Runge-Kutta method (69). For this, the Runge-Kutta technique is used to solve the dynamical system (69) using the following initial conditions and for various parameters: \(a=0.2,~d=0.3,~c=0.2,~b=0.3,~\eta =0.4,~\omega =2.1\):

-

\((T_{1},T_{2}) = (1.5, 0)\) in yellow line, \((T_{1},T_{2}) = (0,2.5)\) in black line (see the Fig. 6);

-

\((T_{1},T_{2}) = (2.9, 0)\) in yellow line, \((T_{1},T_{2}) = (0, 2.9)\) in black line (see the Fig. 7);

-

\((T_{1},T_{2}) = (9.09, 0)\) in yellow line, \((T_{1},T_{2}) = (4.6, 0)\) in black line and \((T_{1},T_{2}) = (2.09, 2.6)\) in red (see the Fig. 8).

The dynamical system’s stability can be significantly impacted by even minor adjustments to the starting values, as this illustrates. The system is extremely sensitive to even little variations between the two initial states, as demonstrated by these observations.

Sensitive analysis of the dynamical system (69) for \(a=0.2,~d=0.3,~c=0.2,~b=0.3,~\eta =0.4,~\omega =2.1\).

Sensitive analysis of the dynamical system (69) for \(a=0.2,~d=0.3,~c=0.2,~b=0.3,~\eta =0.4,~\omega =2.1\).

Sensitive analysis of the dynamical system (69) for \(a=0.2,~d=0.3,~c=0.2,~b=0.3,~\eta =0.4,~\omega =2.1\).

Results and discussion

This section emphasizes the uniqueness of the current study by providing a thorough comparison between the calculated findings and data that have already been acquired. Notably, Alam et al.24 used the Kudryashov approach to successfully extract some exact solutions for the TSFSNM. On the other hand, our research covers a wide variety of solutions, each shown graphically, including bright, dark, combination, exponential, hyperbolic, and trigonometric soliton solutions wave solutions by utilizing two computational techniques. Furthermore, as bifurcation and sensitivity analysis are crucial in dynamical systems, we thoroughly examine the aforementioned model. With their many uses in various scientific fields, chaos theory and bifurcation theory are both valuable instruments for comprehending complex systems. These investigations shed light on the underlying dynamics and phase transitions, which are crucial for understanding qualitative changes in solutions when system parameters alter. A significant limitation of this research is that the proposed methods fail to produce a solvable system of nonlinear algebraic equations when the highest-order derivative terms in the reduced nonlinear ordinary differential equation (ODE) are not consistently balanced with the nonlinear components, representing a primary drawback of the approaches. The physical representations of the extracted solutions, illustrated in Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17, are obtained through analytical techniques. The results are presented as 2D and 3D plots, along with contour visualizations. This work finds applications in nonlinear dynamics, engineering fields, and mathematical physics, such as biosciences, neurosciences, plasma physics, geochemistry, and fluid mechanics. The TSFSNM effectively models complex wave phenomena, capturing memory effects and localized soliton behavior in diverse scientific systems.

Conclusion

This work illuminated the complex dynamics of fractional-order nonlinear systems by analyzing the time-space fractional soliton neuron model (TSFSNM) utilizing the modified Sardar sub-equation (MSSE) method and the improved \(\mathscr {F}\)-expansion method to generate analytical solutions. An understanding of the stability and versatility of solitary wave solutions was provided by the bifurcation and sensitivity analyses, which demonstrated crucial implications of the model’s behavior on fractional parameters. These results highlight the adaptability and relevance of the TSFSNM in a wide range of fields, such as engineering, nonlinear dynamics, mathematical physics, and applied science. In the fields of biosciences, neuroscience, plasma physics, geochemistry, and fluid mechanics, where comprehension of intricate wave interactions is crucial, the model has the potential to significantly advance research. This study opens the door for more research into fractional soliton models’ ability to describe and forecast nonlinear processes in a variety of scientific and engineering situations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, B., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Eskandari, Z. & He, Q. Bifurcation analysis and complex dynamics of a Kopel triopoly model. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 426, 115089 (2023).

El-Shorbagy, M. A., Akram, S. & Mati, R. Propagation of solitary wave solutions to (4+ 1)-dimensional Davey-Stewartson–Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation arise in mathematical physics and stability analysis. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 10, 100669 (2024).

Ali, A., Ahmad, J. & Javed, S. Exact soliton solutions and stability analysis to (3+ 1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger model. Alex. Eng. J. 76, 747–756 (2023).

Ali, A., Ahmad, J. & Javed, S. Exploring the dynamic nature of soliton solutions to the fractional coupled nonlinear Schrödinger model with their sensitivity analysis. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(9), 810 (2023).

Eskandari, Z., Avazzadeh, Z., Ghaziani, R. K. & Li, B. Dynamics and bifurcations of a discrete-time Lotka-Volterra model using nonstandard finite difference discretization method. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. (2022).

Akram, S., Ahmad, J., Alkarni, S. & Shah, N. A. Exploration of solitary wave solutions of highly nonlinear KDV-KP equation arise in water wave and stability analysis. Results Phys. 54, 107054 (2023).

Mahmood, T., Alhawael, G., Akram, S. & Rahman, M. Exploring the Lie symmetries, conservation laws, bifurcation analysis and dynamical waveform patterns of diverse exact solution to the Klein-Gordan equation. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(12), 1978 (2024).

He, Q., Xia, P., Hu, C. & Li, B. Public Information, actual intervention and intflation expectations. Transform. Bus. Econ.21 (2022).

Zhu, X., Xia, P., He, Q., Ni, Z. & Ni, L. Ensemble classifier design based on perturbation binary salp swarm algorithm for classification. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci.135(1) (2023).

Faridi, W. A. et al. Analyzing optical soliton solutions in Kairat-X equation via new auxiliary equation method. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(8), 1317 (2024).

Muflih Alqahtani, A., Akram, S. & Alosaimi, M. Study of bifurcations, chaotic structures with sensitivity analysis and novel soliton solutions of non-linear dynamical model. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 18(1), 2399870 (2024).

Islam, S. M. R. Bifurcation analysis and exact wave solutions of the nano-ionic currents equation: Via two analytical techniques. Results Phys. 58, 107536 (2024).

Dutta, S., Chatterjee, P., Mondal, K. K., Nasipuri, S. & Mandal, G. Solitons and resonance in fractional Sawada-Kotera equation using Hirota bilinear method. In International Conference on Nonlinear Dynamics and Applications, 172–185 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024).

Yadav, S., Singh, M., Singh, S., Heinrich, S. & Kumar, J. Modified variational iteration method and its convergence analysis for solving nonlinear aggregation population balance equation. Comput. Fluids 274, 106233 (2024).

Wazwaz, A.-M., Alhejaili, W. & El-Tantawy, S. A. Optical solitons for nonlinear Schrödinger equation formatted in the absence of chromatic dispersion through modified exponential rational function method and other distinct schemes. Ukr. J. Phys. Opt 25(5), S1049–S1059 (2024).

Furuya, T., Kow, P.-Z. & Wang, J.-N. Consistency of the Bayes method for the inverse scattering problem. Inverse Prob. 40(5), 055001 (2024).

Farooq, A., Ishfaq Khan, M. & Ma, W. X. Exact solutions for the improved mKdv equation with conformable derivative by using the Jacobi elliptic function expansion method. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(4), 542 (2024).

Wang, K.-J. & Shi, F. Multi-soliton solutions and soliton molecules of the (2+ 1)-dimensional Boiti-Leon-Manna-Pempinelli equation for the incompressible fluid. Europhys. Lett. 145(4), 42001 (2024).

Alkahtani, B. S. T. Propagation of wave insights to the Chiral Schrödinger equation along with bifurcation analysis and diverse optical soliton solutions. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 22650 (2024).

Oksendal, B. Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Singh, P. & Senthilnathan, K. Evolution of a solitary wave: optical soliton, soliton molecule and soliton crystal. Discover Appl. Sci. 6(9), 464 (2024).

Younas, U., Yao, F., Nasreen, N., Khan, A. & Abdeljawad, T. On the dynamics of soliton solutions for the nonlinear fractional dynamical system: Application in ultrasound imaging. Results Phys. 57, 107349 (2024).

Badshah, F., Tariq, K. U., Bekir, A., Kazmi, S. M. R. & Az-Zo’bi, E. Stability analysis and solitons solutions of the (1+ 1)-dimensional nonlinear chiral Schrödinger equation in nuclear physics. Commun. Theor. Phys. (2024).

Alam, M.N. & Azizur Rahman, M. Study of the parametric effect of the wave profiles of the time-space fractional soliton neuron model equation arising in the topic of neuroscience. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 100985 (2024).

Abbas, S. et al. Heat and mass transfer through a vertical channel for the Brinkman fluid using Prabhakar fractional derivative. Appl. Therm. Eng. 232, 121065 (2023).

El-Shorbagy, M. A., Akram, S., Rahman, M. & Nabwey, H. A. Analysis of bifurcation, chaotic structures, lump and \(M--W\)-shape soliton solutions to (2+ 1) complex modified Korteweg-de-Vries system. AIMS Math. 9(6), 16116–16145 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R526), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-526), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-526), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors have equally contributed to the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alzaid, S.S., Alkahtani, B.S.T. Exploration of bifurcation, chaos and novel optical dromions solution of the fractional nonlinear dynamical model. Sci Rep 15, 23112 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04731-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04731-9