Abstract

The temporal dynamics of phage-host interactions within full-scale biological wastewater treatment (BWT) plants remain inadequately characterized. Here, we provide an in-depth investigation of viral and bacterial dynamics over a nine-year period in an activated sludge BWT plant, where bleach addition was applied to control sludge foaming. By conducting bioinformatic analyses on 98 metagenomic time-series samples, we reconstructed 3,486 bacterial genomes and 2,435 complete or near-complete viral genomes, which were classified into 361 bacterial and 889 viral clusters, respectively. Our results demonstrate that the primary bleaching event induced significant shifts in both bacterial and viral communities, as well as in virus-host interactions, as evidenced by alterations in bacteria-virus interaction networks and virus-to-host ratio dynamics. Following bleaching, the bacteria-virus network became less interconnected but more compartmentalized. Viral communities mirrored bacterial dynamics, indicating a strong coupling in phage-host interactions. Among the identified virus-host pairs, many exhibited a decelerating rise in viral abundance relative to host abundance, with virus-to-host ratios generally displaying a negative correlation with host abundance. This trend was particularly pronounced in virus-host pairs where viruses harbored integrase genes, indicative of temperate dynamics resembling a “Piggyback-the-Winner” model. Notably, the bleaching intervention appeared to induce a transition from lysogeny to lysis in viruses associated with some foaming-related bacterial species, suggesting a potential virus-involved indirect mechanism by which bleaching mitigates sludge foaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological wastewater treatment (BWT) systems are important man-made ecosystems designed to remove pollutants from municipal and industrial wastewater before discharge. BWT systems rely heavily on diverse microbial communities to degrade organic matter and remove nutrients1. Notably, within the complex BWT microbial ecosystem, in addition to bacteria, there exists a vast population of viruses that infect bacteria, known as bacteriophages (phages), often outnumbering bacteria by many folds2,3. Despite numerous studies highlighting the critical roles of phages in shaping microbial communities, driving bacterial evolution, and mediating biogeochemical cycles in various ecosystems, particularly marine environments4,5,6,7, their activity, function, and interactions with bacteria within the engineered BWT ecosystems remain largely unexplored8.

Bacteriophages are broadly categorized into two groups: lytic phages and temperate phages9. The immediate infection and subsequent lysis caused by lytic phages may significantly impact BWT microbiota10,11. The interactions between temperate phages and their hosts, however, are more intricate. Temperate phages hide in host cells (termed prophage) akin to “molecular time bombs”, which, when triggered, can cause widespread host cell lysis, disturbing microbial community structure and function. For example, Choi et al. observed that various environmental stressors commonly encountered in wastewater treatment could activate prophages in Nitrosospira multiformis12. Similarly, research by Motlagh et al. found that some anthropogenic stress factors (copper, cyanide, and ciprofloxacin) may lead to prophage induction in laboratory wastewater treatment reactors13. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that operational practices in wastewater treatment, particularly the addition of chemical agents such as bleach, might alter the lysogeny-lysis equilibrium of temperate phages. However, our current understanding of these phage-related intrinsic biological interactions in BWT ecosystems remains limited.

Current researches on phage dynamics in wastewater treatment systems mainly focuses on lytic phages. The Kill-the-Winner (KtW) model, a widely accepted prediction on lytic dynamics, predict that density- and frequency-dependent viral predation suppresses blooms of rapidly growing hosts14,15. Shapiro et al. provided empirical support for KtW-like dynamics in a large-scale membrane reactor using plaque-forming assays over 462 days16. In contrast, despite indications of prevalence of lysogenic bacteria in BWT microbiota17, temperate phage dynamics in the BWT environment are much less studied. Contrary to the prevailing view that lysogeny is more common at low host densities, Knowles et al. introduced the Piggyback-the-Winner (PtW) model, which points that temperate phages increasingly adopt a lysogenic strategy as host density rises, particularly within dense communities. This pattern, characterized by log-transformed microbial and viral abundances with slopes significantly less than 1, appears ubiquitous across various ecosystems14. Given the high density of microbial communities in BWT systems, such as activated sludge systems, where bacterial cell counts can reach 108–109 cells/mL18, it is plausible that PtW-like temperate dynamics may be prevalent in the dense BWT communities.

To elucidate phage-host interaction dynamics in environments, longitudinal studies that simultaneously track phage and host dynamics are crucial. The limitations of host-dependent phage isolation have long hampered the dissection of phage ecology in complex ecosystems8. However, advances in bioinformatics have recently made it possible to directly analyze viromes or identify viral sequences from metagenomic data using tools like VirSorter2, VIBRANT, and DeepVirFinder19. Particularly noteworthy is the development of PHAMB, a tool that allows for the extraction of high-quality viral metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from bulk metagenomic datasets20. These viral MAGs can be linked to bacterial MAGs derived from the same metagenome through CRISPR spacer-based approaches, thereby facilitating the investigation of phage-host interactions via abundance dynamics.

In this study, we performed bioinformatic analyses to mine viral data from 98 activated sludge metagenomes collected monthly over nine consecutive years from the Shatin Sewage Treatment Plant in Hong Kong21. During the sampling period, in response to the sludge foaming issue, bleach (sodium hypochlorite) was added to the treatment plant, which led to significant changes in the composition of the sludge bacterial community21. This longitudinal metagenomic dataset provides an unparalleled opportunity to investigate the dynamics of microbial communities in BWT systems and their response to operational interventions. Herein, viral MAGs and bacterial MAGs were concurrently isolated from the metagenomes and their associations were established using CRISPR spacer matching. Our study aims to uncover the long-term temporal dynamics of phage-host interactions during wastewater treatment, with a focus on the effects of interventions, especially bleaching treatment, on these relationships.

Materials and methods

Metagenomic datasets

The metagenomic sequencing data of 98 activated sludge samples were downloaded from NCBI Sequence Read Archive with accession number of PRJNA432264. These samples represent a nine-year time series (June 2007 to December 2015) collected monthly from a single sampling point at the Shatin wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in Hong Kong, with four months not sampled (September 2007, March 2008, July 2008, and March 2012). As detailed by Wang et al.21, all samples were first diluted with absolute ethanol at a 1:1 volume ratio to fix the biomass and then stored at − 20 °C. DNA extraction was performed on approximately 200 mg pellets obtained from 1 mL aliquots of diluted samples through centrifugation. The extraction process utilized the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, USA). Seasonal sludge foaming issues prompted a series of interventions at the treatment plant. Small-scale trials were initiated in late December 2009, followed by full-scale trials involving bleach solution (sodium hypochlorite) addition from February 2010. Continuous sodium hypochlorite addition to the aeration tanks was implemented from January 1 to May 31, 2011. For the remaining months, batch additions were employed in response to foaming events, with cessation of addition in mid-2013.

Binning and taxonomic assignment of bacterial genomes

The raw metagenomic reads were quality-controlled using the metaWRAP-Read_qc module in MetaWRAP, with default parameters for trimming and contamination removal22. Each metagenomic sample was then assembled individually using Megahit v.2.0, retaining only contigs ≥ 500 bp. Subsequently, the quality-controlled reads of each sample were mapped to the combined assembled contig set by Minimap2 v2.26-r117523 employing ‘-N 50’ and filtered by samtools v.1.7 using ‘-F 3584′24.

Metagenomic assemblies were binned by running VAMB v.3.1, a variational autoencoder-based binner, which automatically groups per-sample bins into clusters with high taxonomic consistency, allowing precise strain-resolution taxonomic profiling25. Bacterial bins were identified using CheckM2 v.1.0.2, and bins with a completeness of > 50% and contamination < 10% were retained for further analysis26. Taxonomic classification of each bacterial bin was determined using GTDB-TK v.2.3.2 with the ‘classify_wf’ function, based on the GTDB database release 21427.

Recovery, functional annotation, and host prediction of viral genomes

Viral metagenome-assembled genomes were extracted from bulk metagenomic data using PHAMB, a recently developed pipeline demonstrating high accuracy (93–99%) in phage genome classification20. Contigs within all VAMB bins were searched for viral proteins using hmmsearch v. 3.3.228 against the VOGdb database (https://vogdb.csb.univie.ac.at). Bacterial contamination was determined by searching for hallmark bacterial genes using hmmsearch against the miComplete bacterial marker HMM database (v.1.1.1)29. Viral scores were calculated for each contig using DeepVirFinder with default parameters30. These annotations were integrated into PHAMB’s random forest model, ultimately yielding viral predictions. The quality of PHAMB-predicted viral bins was examined using CheckV v1.0.1 with the parameter ‘end_to_end’ and CheckV database (v1.0)31. The CheckV genome result tables were carefully parsed to viral bins that were annotated as complete and high-quality (> 90% completeness) viruses without contamination. Furthermore, those bins flagged with warnings for “no viral genes detected” and “contig > 1.5 × longer than expected genome length” (indicative of overcomplete-genomes) were excluded from further analysis. The viral bins obtained were grouped into viral clusters (VCs) according to VAMB automatic clustering.

Viral bins were linked to hosts using CRISPR spacer analysis. CRISPR arrays were extracted from the obtained VAMB bacterial bins using CCtyper v1.8.0 with default settings to identify protospacers32. Phage-host relationships at the species level were then predicted by matching the recovered viral bins with the CCtyper spacers using SpacePHARER v5.c2e680a, a de novo prediction tool that enhances sensitivity by comparing spacers and phages at the protein level33. Furthermore, the potential host identities of VCs of interest were further assessed with the assistance of the PHASTEST web server34.

To examine the presence of integrase genes in viral genomes, we predicted genes encoded by the viral genomes using MetaGeneMark35 and subsequently annotated these genes using eggNOG-mapper v2.1.12 based on the eggNOG database v5.0.236.

Calculation of relative abundance

The relative abundance of each bacterial or viral bin was calculated in the unit of RPKM (reads per kilobase sequence per million mapped reads, as detailed in Eq. (1) using CoverM v0.7.0 (https://github.com/wwood/CoverM) on the function ‘genome’. To determine the sample abundance for each viral or bacterial population, the average RPKM was computed across all bins associated with a particular VAMB cluster, as illustrated in Eq. (2).

Bacteria-virus networks analysis

Bacteria-virus networks before and after bleaching were constructed based on the obtained bacterial and viral clusters, focusing exclusively on bacteria-virus interactions while excluding bacteria-bacteria and virus-virus interactions. To avoid the influence of minor potentially spurious bacterial and viral clusters on network relationships, we restricted the analysis to major clusters with a relative abundance exceeding 0.1% in at least 50% of the samples for both bacterial and viral clusters. The networks were generated using SpiecEasi with the sparse graphical lasso (glasso) approach37. Visualization of the networks was conducted in R using the package igraph. The modularity index, assortativity coefficient, degree centrality, and other network-related indices were computed by package igraph to assess changes in the bacteria-virus network before and after bleaching. The permutation test and Mann–Whitney U test were applied to evaluate differences in betweenness centrality between bacteria and viruses in their interaction network, assessing the impact of bleaching. Additionally, the data were reanalyzed using a more stringent 70% prevalence threshold to ensure robustness of the findings.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and data visualization were conducted using Origin, R v4.3.3, and Python v3.12.2. Heatmaps were generated using the ‘pheatmap’ R package. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was performed on Bray–Curtis distances, with 95% confidence ellipses generated using the ‘vegan’ and ‘ggplot2’ R packages. The relationship between viral and bacterial community structures was assessed through Procrustes analysis (PCoA-based). Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between log-transformed viral and host abundances (RPKM). We performed t-tests to determine if the regression slopes significantly differed from 1 or 0, testing the null hypothesis that the slope is not equal to 1 or 0 against the two-sided alternative14. Differences in bacterial abundance, viral abundance, and virus-to-host abundance ratio (VHR, computed by dividing RPKMVC by RPKMBC) before and after bleach addition were assessed using t-tests. Mantel tests with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to explore relationships between host abundance, viral abundance, VHR, and environmental factors. To elucidate the influence of environmental factors on VHR distribution, distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) was conducted using Hellinger-transformed VHR data and log-transformed environmental variables, with significance assessed using Monte Carlo permutation tests.

Results

Viral and bacterial community

Metagenomic analysis of 98 time-series wastewater treatment plant sludge samples yielded 3,486 bacterial genomes (completeness > 0.5, contamination < 0.1) using VAMB, which were grouped into 361 bacterial clusters25. Subsequent analysis with PHAMB19 identified 889 viral clusters (VCs), comprising 2,435 high-quality viral genomes (> 90% completeness). Statistical analysis of the microbial community was performed based on the abundance profiles (RPKM) of these viral and bacterial clusters. PCoA ordination revealed distinct clustering of viral communities in samples collected before (2007–2009) and after (2010–2015) the bleaching event (Fig. 1a), similar to the patterns observed in the bacterial community (Fig. S1)21. A marked shift in Bray–Curtis similarity coincided with the primary bleaching event, while the microbial community remained relatively stable before and after (Fig. 1c). Procrustes rotation demonstrated strong coupling (M2 = 0.083, r = 0.958, P = 0.001) between the viral and microbial ordinations (Fig. 1b). A Mantel test with Spearman’s rank correlation (nperm = 9,999) also confirmed a significant correlation between the viral and bacterial communities (r = 0.942, P = 0.001).

Dynamics of microbial community. (a) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination of viral community composition before (2007–2009) and after (2010–2015) the bleaching event, with 95% confidence ellipse. (b) Procrustes analysis of bacterial and viral communities (Procrustes sum-of-squares M2 = 0.0829, R = 0.9577, P = 0.001). (c) Bray–Curtis dissimilarity changes of bacterial and viral communities.

Virus and host abundance

Host prediction for the 889 VCs was performed using Spacepharer, based on CRISPR spacers identified in the 3,486 bacterial VAMB bins. This approach successfully assigned hosts to 88 VCs, with the majority (n = 53) associated with the Pseudomonadota phylum. Other represented phyla included Chloroflexota (n = 12), Actinomycetota (n = 10), Bacteroidota (n = 9), Calditrichota (n = 2), and Nitrospirota (n = 2) (Fig. S2). At the bacterial species level, 45 virus-host pairs were established, enabling a fine-grained analysis of phage-host interactions within the activated sludge ecosystem. Functional annotation using eggNOG revealed that 44.7% of VCs (n = 397), including those of the majority of virus-host pairs (34 out of 45), encoded integrase genes required for stable lysogeny14. Host-assigned VCs exhibited significantly higher integrase prevalence (67.05%, n = 59) compared to unassigned viral clusters (42.20%, n = 338).

Following the primary bleaching event, among the 45 virus-host pairs, 35.6% of hosts (n = 16) showed a significant (t-test, P < 0.05) decrease in abundance, while 57.8% (n = 26) exhibited a significant increase. For viruses, 15.6% (n = 7) decreased significantly, whereas 66.7% (n = 30) increased significantly post-bleaching. Further analysis revealed that 60% of virus-host pairs (n = 27) showed synchronous increases in abundance following bleaching, while 20% (n = 9) showed simultaneous declines. Notably, 6 virus-host pairs displayed inverse abundance patterns, with significant host decreases accompanied by viral increases (Fig. S3, Table S2). These pairs involved JAMLGM01 sp023957975 (NCBI name: Microthrixaceae bacterium), Gordonia sp020438995, 62–47 sp020441545 (Rhizobiales bacterium 62–47), Ottowia sp024235955, Albidovulum sp024236495, and UBA11426 sp003448375 (Bacteroidota bacterium), along with their corresponding VCs. Notably, VHR remained statistically unchanged in 22.86% (n = 8) of integrase-carrying pairs after bleaching, while an even higher proportion—36.36% (n = 4)—of non-integrase pairs showed no significant changes.

Linear regression analyses were performed on the log-transformed host and viral abundances (RPKM) for each virus-host pair across the whole sampling period (2007–2015) (Table S3). Of the 45 identified virus-host pairs, 31 pairs exhibited positive regression slopes less than 1. Among these, 22 pairs demonstrated slopes significantly less than 1 (Pm≠1 < 0.05), with the majority (n = 19) containing VCs harbouring integrase genes. Notably, JAMLGM01 sp023957975 and its viruses demonstrated a significant negative correlation (Pm≠0 < 0.01). To examine potential perturbations in phage-host interactions due to the bleaching event, separate regression analyses for pre- and post-bleaching periods were also performed (Table S3 and Fig. S4). Prior to bleaching (2007–2009), 35 virus-host pairs displayed regression slopes between 0 and 1, with 27 pairs containing VCs carrying integrase genes and 23 slopes significantly less than 1. Post-bleaching (2010–2015), 26 virus-host pairs maintained this pattern, with 19 slopes significantly less than 1. Remarkably, 22 virus-host pairs exhibited positive regression slopes less than 1 in both periods, with 13 pairs (11 containing VCs with integrase genes) maintaining significance. Intriguingly, two virus-host pairs with overall negative regression slopes (hosts: JAMLGM01 sp023957975 and Albidovulum sp024236495) displayed positive correlations between host and viral abundances in both pre- and post-bleaching periods.

Bacteria-virus networks

To elucidate the impact of bleaching on bacteria-virus interactions within the activated sludge system, we constructed co-occurrence networks based on a prevalence threshold of 50%. The networks comprised 286 nodes (159 bacterial, 127 viral), with 67 VCs (viral nodes in networks) encoding integrase genes. Prior to bleaching treatment, analysis of network topology revealed a mean degree centrality of 4.73 ± 7.75, indicative of the average number of connections per node, with a total of 676 interactions observed (Fig. 2a). Following bleaching, the bacteria-virus interaction network underwent significant restructuring (significance tests of betweenness centrality, P < 0.01). The average degree centrality decreased to 2.50 ± 3.02, with a substantial decline in total interactions to 358 (Fig. 2b). Notably, VCs containing integrase exhibited a greater average reduction in degree centrality (−3.31) compared to those without integrase (−1.60), suggesting a differential impact of integrase on network connectivity. This reduced connectivity was accompanied by an increase in modularity from 0.38 to 0.70. Of the 127 VCs engaged in bacteria-virus networks, integrase-harboring VCs showed increased modularity participation, rising from 34 pre-bleaching to 47 post-bleaching. Furthermore, the assortment coefficient, a measure of the tendency for nodes to connect with similar nodes, rose from 0.68 to 0.83. Among VCs, the mean change in betweenness centrality before and after bleaching was 192.24 for integrase-containing viral clusters, compared to 154.40 for those without integrase. Repeating the analysis with an increased prevalence threshold from 50 to 70% revealed similar trends of bleaching effect on the bacterial-viral network, indicating that the initial threshold setting did not bias the results.

Co-occurrence networks of bacteria-virus interactions. (a) Bacteria-virus network before bleaching (2007–2009). (b) Bacteria-virus network following the bleaching treatment (2010–2015). Both networks were constructed using bacterial and viral clusters identified with a prevalence greater than 50% across 98 samples. Only bacteria-virus interactions were retained in the networks. The colors of the nodes indicate their membership in different modules, with each module represented by a different color.

Virus-to-host ratio

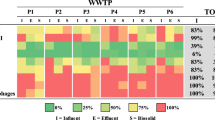

We calculated the virus-to-host ratio (VHR) for each virus-host pair, a metric commonly employed to study virus-bacteria relationships in diverse environments (Table S4)38. PCoA and heatmap analyses (Fig. 3a and b) revealed a marked shift in VHR patterns following the primary bleaching event. Significant different VHR patterns were observed between the pre- and post-bleaching periods in 73.3% of virus-host pairs (n = 33, P < 0.05). Mantel tests were conducted to assess correlations between various environmental factors and VHR, virus abundance, and host abundance across 45 virus-host pairs (Fig. S5a). Modest correlations were observed between mean cell residence time (MCRT) and host abundance, virus abundance, and VHR (Mantel’s r > 0.15, P < 0.01). To explore the relationship between VHR and host abundance further, we performed Spearman correlation analyses (Fig. 3c and Table S5). These analyses revealed significant positive correlations between VHR and host abundance in 13 virus-host pairs (P < 0.05), with over half of these pairs (n = 7) lacking VCs carrying integrase genes. In contrast, 21 virus-host pairs exhibited significant negative correlations, of which 81% (n = 17) had VCs carrying integrase genes. Distance-based Redundancy Analysis (dbRDA) was employed to elucidate the relationship between VHRs and environmental variables. We found that five virus-host pairs exhibited significant correlations with specific environmental factors (Fig. S5b). Specifically, the VHR associated with JAMLGM01 sp023957975 exhibited a strong positive correlation with MCRT, while those associated with Agitococcus sp024234595 and GCA-2699125 sp020634455 (Anaerolineales bacterium) demonstrated positive correlations with mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS) and temperature, respectively. Strong negative correlations were observed between MCRT and VHRs associated with JACJXW01 sp020636095 and Nitrosomonas sp020446045.

Temporal dynamics of phage-host interactions. (a) Heatmap of virus-host rations (VHRs) dynamics for 45 virus-host pairs over a nine-year period, with bleach addition events marked by red lines. Asterisks denote significant differences in VHRs between the pre-bleaching (2007–2009) and post-bleaching (2010–2015) periods. (b) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination of VHRs before and after bleach addition. (c) Spearman rank correlation between VHR and host abundance, with viral clusters harboring integrase genes highlighted (green bar). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks: *** (P < 0.001), ** (P < 0.01 and > 0.001), * (P < 0.05 and > 0.01).

Viruses linked to foaming species

Among the 45 virus-host pairs, 6 were linked to the hosts associated with sludge foaming, including Gordonia sp020438995, Mycobacterium sp020438905, Promineofilum sp020634335, Skermania piniformis, and two species from the family Microtrichaceae (JAMLGM01 sp023957975 and JAMLGJ01 sp023958095) (Fig. 4a)39. The bleaching treatment significantly reduced the abundance of these six foaming-associated species (P < 0.05, Table S2). However, the corresponding changes in viral abundance exhibited diverse patterns. Viral abundance increased for JAMLGM01 sp023957975, Gordonia sp020438995, and S. piniformis following bleaching. The most pronounced increase was observed for JAMLGM01 sp023957975, with viral abundance rising significantly from a mean of 0.01 to 0.38 RPKM (P < 0.01; Tables S1 and S2). The abundance of S. piniformis viruses, which lack an encoded integrase gene, did not show a significant increase (P = 0.536). In contrast, the average viral abundance for the other three foaming-associated bacteria decreased, with JAMLGJ01 sp023958095 and Mycobacterium sp020438905 demonstrating significant reductions (P < 0.01). Despite the disparate responses in viral abundance, the virus-to-host ratio exhibited a consistent increase across all foaming-associated virus-host pairs following the primary bleaching event. Statistically significant VHR increases (P < 0.01) were observed in four virus-host pairs, corresponding to the hosts JAMLGM01 sp023957975, Gordonia sp020438995, Mycobacterium sp020438905, and Promineofilum sp020634335 (Table S2). Notably, the virus-host pair associated with JAMLGM01 sp023957975 demonstrated a remarkable 557-fold increase in mean VHR post-bleaching, followed by a tenfold increase for Gordonia sp020438995. Among these four virus-host pairs, all except the one associated with Promineofilum sp020634335 encoded integrase genes in their corresponding VCs.

Changes in abundance and viral-to-host ratio (VHR) of virus-host pairs related to sludge foaming. (a) Comparison of viral and host abundances before (2007–2009) and after (2010–2015) the bleaching event. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks: *** (P < 0.001), ** (P < 0.01 and > 0.001), * (P < 0.05 and > 0.01). (b) Temporal dynamics of host abundance, viral abundance, and VHR for the virus-host pairs associated with JAMLGM01 sp023957975 and Gordonia sp020438995, respectively.

An intriguing pattern emerged in the dynamics of Gordonia sp020438995 and its associated viruses (Fig. S6). This virus-host pair exhibited remarkable periodic synchronous fluctuations in both abundances and VHRs, with a consistent periodicity of approximately six months (Fig. 4b). Following the bleaching event, the cyclical pattern continued, but with notably lower peak host abundances and considerably higher VHR peaks compared to pre-treatment levels.

Discussion

Consistent with the previous study21, using a VAMB-based genome-centric analysis, we observed significant differences in the sludge bacterial community composition before and after the bleaching event (Fig. S1). The viral community mirrored the changing pattern of the bacterial community, as expected due to phages’ reliance on bacterial hosts for reproduction. Wang et al.’s virome analysis also revealed distinctly different viral population dynamic patterns before and after bleach treatment40. Thus, following the bleaching disturbance, both communities underwent a sudden transition to a relatively stable state (Fig. 1a and c). The dramatic community variations after bleaching support the concept that ecological systems can undergo state shifts when the degree of a perturbation exceeds an allowable capacity41. Procrustes analysis and Mantel tests further revealed a strong coupling between viral and bacterial communities within this full-scale wastewater treatment facility (Fig. 1b). This aligns with our previous findings on viral dynamics in laboratory-scale activated sludge reactors17, underscoring the close interactions between viral and bacterial communities in BWT systems.

The observed alterations in bacteria-virus network topology reflect the significant impact of bleaching treatment on bacteria-virus interaction. Following bleaching, the sharp decrease in total interactions (from 676 to 358) and average degree centrality (from 4.73 ± 7.75 to 2.50 ± 3.02) signals a substantial shift in bacteria-virus dynamics, resulting in a less interconnected network. This decline may be attributable to the decay of bleaching-sensitive bacterial or viral populations. Conversely, the increase in modularity indicates a more specialized and compartmentalized network, while the rise in the assortment coefficient suggests a shift toward preferential interactions between similar nodes. The greater elevation of betweenness centrality in integrase-harboring VCs (192.24) versus non-integrase VCs (154.40) post-bleaching, combined with their increased participation in network modularity (rising from 34 to 47 VCs), indicates their ascending ecological importance in mediating post-disturbance interactions. This strengthening of specialized bacteria-virus associations may point to changes in ecological niches. Bleaching causes the decline of bacterial hosts, releasing ecological niches. Integrase-harboring viral clusters can rapidly infect remaining hosts or persist via lysogenic conversion, occupying key ‘intersection points’ across multiple niches. The enhanced capacity for microbial aggregation and biofilm formation post-bleaching could promote the formation of new niches42, thus leading to more specific associations in the post-bleaching network. The virus-to-host ratio (VHR) profiles of established virus-host pairs shifted in a pattern similar to those of the bacterial and viral communities (Fig. 3b). Following the bleaching event, most virus-host pairs experienced significant shifts in VHR, indicating potential changes in viral production or decay, likely due to alterations in the host’s physiological state38,43. Accordingly, the bleaching treatment not only caused substantial changes in the BWT bacterial community composition but also exerted a strong impact on virus-host relationships. However, it is noteworthy that 22.2% of the virus-host pairs (n = 10) did not exhibit significant changes in VHR, despite significant shifts in host abundance post-bleaching (Table S2), suggesting that associated viral production or decay remained unaffected by the bleaching treatment. In addition, the abundance ratio (VHR) of Nitrosomonas sp020446045 and its VCs showed a significant negative correlation with MCRT (Fig. S5). It is known that longer MCRT is more favorable for slow-growing organisms, such as ammonia-oxidizing bacteria21. The result here suggests that as MCRT increases, the reduced predation pressure from phages may also contribute to the increase of ammonia-oxidizing Nitrosomonas species.

A number of identified viral clusters (397 out of 889), including most established virus-host pairs (34 out of 45), carried integrase genes associated with temperate phages, indicating that the activated sludge viral community may harbor abundant temperate phages. This allows for a fine-scale dissection of the dynamics of temperate phages at the host (species)-virus level in dense BWT environments. Over the 9-year operation period, the log–log slopes of the linear regressions between host and virus abundances were non-negative and < 1 for 25 out of the 34 temperate phage-related virus-host pairs, and significantly < 1 for 19 of them. Even after excluding the effect of bleaching treatment, in the 2007–2009 period, 27 out of these 34 virus-host pairs had log–log slopes < 1, with 19 being significantly so. These results suggest that for the majority of virus-host pairs associated with temperate phages, the increase in virus abundance slows down as host abundance increases. This is consistent with the PtW predictions that temperate phages prefer a lysogenic lifecycle as host density increases14, providing empirical support for this theoretical framework at the level of specific virus-host (species) pairs. The relationship between virus-host ratio (VHR) and host abundance also supports this behavioral dynamic of temperate phages to some extent (Fig. 3c). Among the 34 temperate phage-related virus-host pairs, 25 pairs (73.5%) showed negative correlations. This means that as host abundance increases, VHR decreases, which implies a possible decline in virus production capacity, and vice versa. In contrast, most virus-host pairs (7 out of 11) without VCs carrying integrase genes exhibited positive correlations between VHR and host abundance. According to the PtW model, the observed negative correlation may be attributed to the phage life strategy shifting from lytic to lysogenic44. However, it should be noted that the reverse mechanism caused by the bleaching treatment could also lead to the negative correlation. Bleaching could induce prophages within lysogenic bacteria, resulting in increased viral abundance. Concurrently, host abundance decreases due to either the bleaching agent itself, viral lysis, or a combination of both, ultimately leading to a significant increase in VHR.

Among the identified virus-host pairs, the relative abundance of bacteria associated with sludge foaming significantly decreased following the primary bleaching event, highlighting the effectiveness of bleaching treatment (Fig. 4a)45. Interestingly, over two years after halting bleach addition, there was no remarkable increase in the relative abundance of these foaming-associated species (Table S1). It is suggested that beyond environmental conditions, intrinsic biological interactions among microbial community members may play a crucial role in maintaining community stability. Indeed, a correlation-based statistical analysis of bacterial dynamics over five years in the same activated sludge system has previously demonstrated that bacterial interactions are dominant drivers determining bacterial community assembly46. Here, our results provide evidence that phage-host interactions may also contribute to this process. For example, for JAMLGM01 sp02395797, a species in foaming-associated Microthrixaceae, it maintained high abundance prior to the bleaching event, while its corresponding viruses kept at low abundance levels, suggesting weak phage predation pressure during this period. In contrast, following the primary bleaching event, JAMLGM01 sp02395797 experienced a sharp decline in relative abundance, while the corresponding viral abundance significantly increased, with the average VHR post-bleaching treatment exceeding pre-treatment levels by over 557-fold. Another example is Gordonia sp020438995 and its virus, which, although exhibiting periodic fluctuations, also displayed a similar pattern of a sudden viral bloom and host decline following the bleaching treatment (Fig. 4b), with VHR increasing by over tenfold. The viral clusters associated with these species carried integrase genes, indicative of their capacity for lysogeny. In fact, among the > 2000 Gordonia phages isolated to date, the vast majority are temperate47. Thus, it is possible that the bleaching event triggers the lifestyle shift of temperate phages associated with JAMLGM01 sp02395797 and Gordonia sp020438995 from lysogenic towards lytic, subjecting the hosts to high phage predation pressure. Notably, this new established lysogeny-lysis balance appears to be maintained over a long period, as indicated by the relative stable VHR dynamics during the two years following the cessation of bleach addition (Fig. 4b). Therefore, besides the direct destructive effects of bleach on bacterial cells, it also appears to influence the bacterial community of activated sludge by altering the lysogeny-lysis balance of temperate phages, exerting a prolonged impact. However, we found that another member of the Microthrixaceae family, JAMLGJ01 sp023958095, showed a decline in both host and corresponding virus abundances post-bleach treatment, with no significant change in VHR (Table S2). This suggests that bleach does not uniformly induce prophages across different foaming species or strains. While many studies have utilized virulent phages to control sludge bulking or foaming48,49,50, our findings indicate that manipulating the lysogeny-lysis balance of temperate phages could achieve similar outcomes.

Caveats: this study reconstructed viral genomes from microbial metagenomes rather than virus-enriched samples, which may introduce a bias toward primarily capturing intracellular viruses, such as prophages or actively replicating viruses. Nonetheless, our PHAMB-recovered viral bins recruited approximately 21% of sequencing reads from two Shatin WWTP viromes (SRR6747803 and SRR6747804)—substantially more than the ~ 6% recruited by the bacterial bins—suggesting that the recovered viral genomes likely represent not only intracellular forms but also a number of extracellular virions. To achieve a more comprehensive understanding of viral ecology in wastewater systems, future studies should incorporate viral enrichment protocols. In addition, while a CRISPR-based approach was employed to establish specific linkages between the viral clusters and bacterial clusters (essential for computing the virus-host ratio and analyzing virus-host interactions at a finer resolution in this study), only ∼10% of VCs could be linked to BCs. This limited linkage may reduce confidence in extrapolating broader virus-host interaction patterns from the dataset.

Conclusions

In this study, bacteria-virus interaction dynamics were investigated over a nine-year period in an activated sludge BWT plant employing bleach addition for foaming control. The following are the main conclusions drawn from this study.

-

(1)

The bleaching treatment fundamentally altered bacteria-virus interactions, as evidenced by changes in bacteria-virus networks and virus-to-host ratio dynamics.

-

(2)

Bleaching could trigger a lysogeny-to-lysis shift in temperate phages associated with certain foaming-related bacterial species, which may contribute to mitigating sludge foaming.

-

(3)

Changing patterns of the established virus-host pairs indicate that temperate phage dynamics generally follow the “Piggyback-the-Winner” predictions in the dense BWT ecosystem.

Data availability

VAMB bacterial bins (completeness > 0.5, contamination < 0.1) and PHAMB viral bins (> 90% completeness) are accessible under the DOIs https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26340565.v1 and https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26340550.v1, respectively.

References

Chen, G. H., van Loosdrecht, M. C., Ekama, G. A. & Brdjanovic, D. Biological wastewater treatment principles, modeling and design (IWA publishing, 2020).

Otawa, K. et al. Abundance, diversity, and dynamics of viruses on microorganisms in activated sludge processes. Microb. Ecol. 53(1), 143–152 (2007).

Wu, Q. & Liu, W. T. Determination of virus abundance, diversity and distribution in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 43(4), 1101–1109 (2009).

Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Paez-Espino, D., Polz, M. F. & Zhang, T. Prokaryotic viruses impact functional microorganisms in nutrient removal and carbon cycle in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 5398 (2021).

Daly, R. A. et al. Viruses control dominant bacteria colonizing the terrestrial deep biosphere after hydraulic fracturing. Nat. Microbiol. 4(2), 352–361 (2019).

Paez-Espino, D. et al. Uncovering Earth’s virome. Nature 536(7617), 425–430 (2016).

Suttle, C. A. Viruses in the sea. Nature 437(7057), 356–361 (2005).

Tang, X. et al. Phage-host interactions: The neglected part of biological wastewater treatment. Water Res. 226, 119183 (2022).

Madigan, M. T., Clark, D. P., Stahl, D. & Martinko, J. M. Brock biology of microorganisms (Benjamin Cummings, 2010).

Barr, J. J., Slater, F. R., Fukushima, T. & Bond, P. L. Evidence for bacteriophage activity causing community and performance changes in a phosphorus-removal activated sludge. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 74(3), 631–642 (2010).

Shapiro, O. H. & Kushmaro, A. Bacteriophage ecology in environmental biotechnology processes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22(3), 449–455 (2011).

Choi, J., Kotay, S. M. & Goel, R. Various physico-chemical stress factors cause prophage induction in Nitrosospira multiformis 25196–an ammonia oxidizing bacteria. Water Res. 44(15), 4550–4558 (2010).

Motlagh, A. M., Bhattacharjee, A. S. & Goel, R. Microbiological study of bacteriophage induction in the presence of chemical stress factors in enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR). Water Res. 81, 1–14 (2015).

Knowles, B. et al. Lytic to temperate switching of viral communities. Nature 531(7595), 466–470 (2016).

Liu, R. et al. Bacteriophage ecology in biological wastewater treatment systems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105(13), 5299–5307 (2021).

Shapiro, O. H., Kushmaro, A. & Brenner, A. Bacteriophage predation regulates microbial abundance and diversity in a full-scale bioreactor treating industrial wastewater. ISME J. 4(3), 327–336 (2010).

Liu, R. et al. Microbial density-dependent viral dynamics and low activity of temperate phages in the activated sludge process. Water Res. 232, 119709 (2023).

Nielsen, P. H. FISH Handbook for Biological Wastewater Treatment: Identification and Quantification of Microorganisms in Activated Sludge and Biofilms by FISH (IWA publishing, 2009).

Khot, V., Strous, M. & Hawley, A. K. Computational approaches in viral ecology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 18, 1605–1612 (2020).

Johansen, J. et al. Genome binning of viral entities from bulk metagenomics data. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 965 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Successional dynamics and alternative stable states in a saline activated sludge microbial community over 9 years. Microbiome 9(1), 199 (2021).

Uritskiy, G. V., DiRuggiero, J. & Taylor, J. MetaWRAP-a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6, 158 (2018).

Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34(18), 3094–3100 (2018).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25(16), 2078–2079 (2009).

Nissen, J. N. et al. Improved metagenome binning and assembly using deep variational autoencoders. Nat. Biotechnol. 39(5), 555–560 (2021).

Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM2: A rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat. Methods 20(8), 1203–1212 (2023).

Chaumeil, P. A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: A toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 36(6), 1925–1927 (2020).

Potter, S. C. et al. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 46(W1), W200–W204 (2018).

Hugoson, E., Lam, W. T. & Guy, L. miComplete: weighted quality evaluation of assembled microbial genomes. Bioinformatics 36(3), 936–937 (2020).

Ren, J. et al. Identifying viruses from metagenomic data using deep learning. Quant. Biol. 8(1), 64–77 (2020).

Nayfach, S. et al. CheckV assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39(5), 578–585 (2021).

Russel, J., Pinilla-Redondo, R., Mayo-Munoz, D., Shah, S. A. & Sorensen, S. J. CRISPRCasTyper: automated identification, annotation, and classification of CRISPR-Cas Loci. CRISPR J. 3(6), 462–469 (2020).

Zhang, R. et al. SpacePHARER: Sensitive identification of phages from CRISPR spacers in prokaryotic hosts. Bioinformatics 37(19), 3364–3366 (2021).

Wishart, D. S. et al. PHASTEST: Faster than PHASTER, better than PHAST. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(W1), W443–W450 (2023).

Zhu, W., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(12), e132 (2010).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: A hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(D1), D309–D314 (2019).

Yan, M. & Yu, Z. Viruses contribute to microbial diversification in the rumen ecosystem and are associated with certain animal production traits. Microbiome 12(1), 82 (2024).

Parikka, K. J., Le Romancer, M., Wauters, N. & Jacquet, S. Deciphering the virus-to-prokaryote ratio (VPR): Insights into virus-host relationships in a variety of ecosystems. Biol. Rev. 92(2), 1081–1100 (2017).

Dueholm, M. K. D. et al. MiDAS 4: A global catalogue of full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences and taxonomy for studies of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 1908 (2022).

Wang, Y., Jiang, X., Liu, L., Li, B. & Zhang, T. High-resolution temporal and spatial patterns of virome in wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52(18), 10337–10346 (2018).

Ryo, M., Aguilar-Trigueros, C. A., Pinek, L., Muller, L. A. H. & Rillig, M. C. Basic principles of temporal dynamics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34(8), 723–733 (2019).

Battin, T. J. et al. Microbial landscapes: New paths to biofilm research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5(1), 76–81 (2007).

Knowles, B. et al. Temperate infection in a virus-host system previously known for virulent dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 4626 (2020).

Coutinho, F. H. et al. Marine viruses discovered via metagenomics shed light on viral strategies throughout the oceans. Nat. Commun. 8, 15955 (2017).

Jenkins, D., Richard, M. G. & Daigger, G. T. Manual on the Causes and Control of Activated Sludge Bulking, Foaming and Other Solids Separation Problems. (CRC Press, 2003).

Ju, F. & Zhang, T. Bacterial assembly and temporal dynamics in activated sludge of a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. ISME J. 9(3), 683–695 (2015).

Guerrero, L. D. et al. Long-run bacteria-phage coexistence dynamics under natural habitat conditions in an environmental biotechnology system. ISME J. 15(3), 636–648 (2021).

Choi, J., Kotay, S. M. & Goel, R. Bacteriophage-based biocontrol of biological sludge bulking in wastewater. Bioeng. Bugs 2(4), 214–217 (2011).

Petrovski, S., Seviour, R. J. & Tillett, D. Characterization of the genome of the polyvalent lytic bacteriophage GTE2, which has potential for biocontrol of Gordonia-, Rhodococcus-, and Nocardia-stabilized foams in activated sludge plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77(12), 3923–3929 (2011).

Petrovski, S., Seviour, R. J. & Tillett, D. Prevention of Gordonia and Nocardia stabilized foam formation by using Bacteriophage GTE7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77(21), 7864–7867 (2011).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 42377120, No. 42377120, No. 42377120, No. 42377120, No. 42377120, No. 42377120, No. 42377120.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Ruyin Liu and Junge Zhu. Data curation: Peihan Yan.Formal analysis: Peihan Yan, Ruyin Liu and Junge Zhu. Methodology: Peihan Yan and Ruyin Liu. Software: Peihan Yan and Ruyin Liug – original draft: Peihan Yan and Ruyin Liu. Writing & editing: Peihan Yan, Ruyin Liu and Junge Zhu. Peihan Yan, Ruyin Liu, Junge Zhu, Qianwei Ji, Gaolin Hou, Guoqiang Liang and Xinchun Liu reviewed the manuscript. Junge Zhu and Peihan Yan contribute equally to this work as co-first authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, P., Zhu, J., Ji, Q. et al. Significant impact of bleaching treatment on phage-host interaction dynamics in a full-scale wastewater treatment plant. Sci Rep 15, 19165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04743-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04743-5