Abstract

Accurate real-time optical diagnosis that distinguishes neoplastic from non-neoplastic colorectal lesions during colonoscopy can lower the costs of pathological assessments, prevent unnecessary polypectomies, and help avoid adverse events. Using a multistep process, this study developed an explainable artificial intelligence method, niceAI, for classifying hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps. Radiomics and color were extracted, followed by feature selection with deep learning features using Spearman’s correlation analysis. The selected deep features were merged with the narrow-band imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic grading, aligning with endoscopists’ decision-making process to produce an interpretable diagnostic output. Initially, 2,048 deep features were identified; these were reduced to 103 in the second screening, and finally to 14. Similarly, 24 radiomics features were selected, whereas no color features were chosen. Comparative evaluation showed that niceAI had accuracy comparable to that of deep learning models (area under the curve, 0.946; accuracy, 0.883; sensitivity, 0.888; specificity, 0.879; positive predictive value, 0.893; negative predictive value, 0.872). This study introduces a novel system that combines radiomics and deep features to enhance the transparency and understanding of optical diagnosis. This approach bridges the gap between artificial intelligence predictions and clinically meaningful assessments, thereby offering a practical solution for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and clinical decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of death globally1. Colonoscopy, the gold standard for CRC prevention, facilitates the detection and removal of neoplastic colon polyps, and enables real-time optical diagnosis, which is crucial for differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions. Accurate optical diagnosis during colonoscopy can significantly reduce unnecessary polypectomies, lower pathological assessment costs, and prevent adverse events2,3,4,5. Optical diagnosis of colon polyps is typically conducted using endoscopic differentiation criteria during image-enhanced colonoscopy, such as narrow-band imaging (NBI) or flexible spectral imaging color enhancement6,7. The NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic (NICE) classification system (Supplementary Table S1), based on endoscopic features such as surface pattern, vessel shape, and color, is commonly used6. This classification categorizes polyps into three types: adenomatous (AD) polyps, hyperplastic (HP) polyps, and deep submucosal invasive cancers. To implement optical diagnosis with these systems, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy have issued the Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) statement and Simple Optical Diagnosis Accuracy (SODA) benchmarks, respectively3,5. However, many endoscopists, especially those with less experience, struggle to consistently differentiate between neoplastic and non-neoplastic polyps8. Consequently, cost-saving strategies using optical diagnosis, such as “resect and discard” and “diagnose and leave,” are not yet standard care.

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) has emerged as a potential solution to the limitations of human optical diagnosis, enhancing polyp differentiation accuracy (ACC) and aiding clinical decisions9,10,11. However, randomized clinical trials on real-time CADx with colonoscopy have not conclusively demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of CADx12,13,14,15. Current deep learning (DL)-based AI models, which display pathologic diagnoses with or without confidence scores, are often criticized as “black boxes” due to their opaque decision-making processes16,17. Efforts to use multiple DL models and feature extraction techniques for diagnosing critical morphological characteristics have not fully addressed transparency issues18,19. This opacity hampers endoscopists’ trust and acceptance of AI diagnostics20,21,22. Understanding the AI “black box” is essential for trust, error identification, and judgment in AI decisions. Transparency and interpretability allow clinicians to verify AI-generated diagnoses, ensuring error detection and correction, thereby improving reliability and clinical utility of AI systems. To bridge this gap, there is a pressing need for explainable AI systems that mirror clinicians’ decision-making processes. Understanding how model-internal deep features relate to established interpretable features—such as radiomics—can enhance trust and support clinically meaningful interpretations.

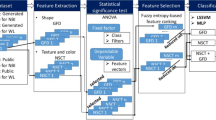

This study introduces a novel explainable approach to optical diagnosis that statistically correlates deep features with interpretable radiomics features aligned with the NICE classification, as labeled by three experienced gastroenterologists (Fig. 1). Rather than introducing a fundamentally new methodology, this study focuses on integrating existing techniques—radiomics, deep learning, and the NICE classification—into a unified framework aimed at improving clinical transparency and usability. By aligning the model’s internal representations with interpretable features familiar to clinicians, our approach enhances the practical applicability of AI-assisted optical diagnosis.

XAI system workflow. The XAI system comprises four integral steps: (1) Data preparation involving radiomics, deep features, and clinician-assigned NICE grading; (2) correlation-driven selection process to identify significant correlations between radiomics and deep features; (3) regression analysis linking the NICE grading to chosen deep features, thereby translating deep learning outcomes into the NICE grading and encompassing feature selection; and (4) reinterpreting the selected deep features in terms of radiomics. NICE, narrow-band imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic.

Results

Demographics comparison between datasets

Characteristics of the training (Dataset A and B) and test (Dataset C) datasets are described in Table 1. In the Chi-square statistical analysis, the P values were determined as follows: for morphology, Dataset A vs. Dataset B was P = 0.011, Dataset A vs. Dataset C was P = 0.298, and Dataset B vs. Dataset C was P = 0.207; for histology, Dataset A vs. Dataset B was P < 0.001, Dataset A vs. Dataset C was P < 0.001, and Dataset B vs. Dataset C was P = 0.494; for location, Dataset A vs. Dataset B was P = 0.036, Dataset A vs. Dataset C was P < 0.001, and Dataset B vs. Dataset C was P = 0.082; and for size, Dataset A vs. Dataset B was P = 0.221, Dataset A vs. Dataset C was P < 0.001, and Dataset B vs. Dataset C was P < 0.001.

Correlation between noninterpretable and interpretable features (first selection)

No color features were selected during the first screening; however, 103 of 2,048 deep features and 30 of 93 radiomics features were selected. During the first screening process, 439 combinations of deep features and radiomics data exhibited a significant correlation (R > 0.5, P < 0.05).

Regression between noninterpretable and NICE grading (second and third selection)

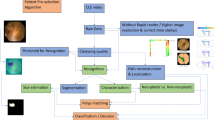

Figure 2 illustrates the second and third screening processes used to build niceAI. During these processes, we compared the performances of different deep features with the NICE feature grading (surface and vessel patterns) using the R2 score, which is a measure of regression performance. The results shown in Fig. 2a and d indicate the number of times each deep feature was selected during the 100 iterations. In the third selection process (Fig. 2e and h), we identified the top-performing combinations of deep features for each NICE feature category: surface pattern Type 1 and 2 and vessel Type 1 and 2. Specifically, we found that the top nine deep features were the most effective for surface pattern Types 1, whereas six deep features were optimal for surface pattern Type 2. Notably, the deep feature “215” was specifically selected for the surface pattern, whereas “702,” “720,” “1,368,” and “1,476” were selected for the vessel pattern (Supplementary Table S2). In addition to the R² score, we evaluated the performance of the selected deep feature combinations using mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), and explained variance score (EVS) at each optimal selection point. Notably, the performance trends remained consistent across these metrics, indicating stable model behavior under different evaluation criteria (Supplementary Fig. S1).

NiceAI diagnosis and performance evaluation

Table 2 lists the diagnostic performance of different models. Among the machine learning (ML) models, the random forest model achieved the highest performance, although it did not surpass an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.900 or ACC of 0.850. For the DL and explainable AI (XAI) models, AUROCs were 0.956 and 0.946 with an ACC of 0.877 (threshold = 0.5) and 0.883 (threshold = 0.4), respectively. The classification performance of niceAI in diagnosing AD and HP polyps was slightly lower than that of DL alone; however, it significantly outperformed the ML models that only used radiomics or color features (p-value in the DeLong test < 0.05) and did not show a significant difference compared with DL (p-value in the DeLong test > 0.05).

Figure 3 shows the AUROC representing the results of niceAI. The performance criteria set by SODA (sensitivity[SEN] > 0.8; specificity [SPE] > 0.9) and PIVI 2 (negative predictive value [NPV] > 0.9 for high confidence images) were both met, indicating successful evaluation. The AUROC curve visually demonstrates the trade-off between SEN and SPE, which are crucial factors for assessing the diagnostic ACC of niceAI. Figure 3a shows the overall performance of niceAI. In Fig. 3b, high-confidence results are selected based on the top 90% confidence levels. Gray dots represent the diagnostic performance when using the clinician NICE feature grading. The detailed performance of niceAI according to the threshold is presented in Supplementary Table S3. The performance of the XAI system for surface patterns and vessels is presented separately in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Classification performance of XAI indicators for diagnosis of AD and HP polyps. (a) XAI performance for the entire test set. (b) XAI performance for high-confidence images; gray dots represent the diagnostic performance of clinicians. AD, adenomatous; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; HP, hyperplastic; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; XAI, explainable artificial intelligence.

Table 3 shows the results of the correlation between the XAI predictions of the NICE grading and actual clinician-assigned NICE grades. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient and Kendall tau correlation results demonstrated high performance, indicating strong consistency between the XAI predictions and expert clinician evaluations.

Interpretation

Table 4 presents the results of the interpretability analysis of the selected radiomics features for the NICE grading. The interpretable value of radiomics features is generally indicated by opposite effects in Types 1 and 2. Among these, “Original_glrlm_RunPercentage” demonstrated the greatest influence on both texture types, albeit in opposite directions. Additionally, “original_glcm_lmc1” and “Original_glszm_Zone%” were significant exclusively for vessel Type 1.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated an XAI system named niceAI that aligns with clinicians’ diagnostic criteria to address the black-box limitations of existing AI systems. Our method used repeatable correlation analysis for reproducibility and explainable features with the NICE grade for clarity. The method demonstrated an area under the curve of 0.946 and achieved the following performance metrics for HP and AD classification with a 0.3 threshold: ACC of 0.883, SEN of 0.888, SPE of 0.879, positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.893, and NPV of 0.872. By integrating deep and interpretable radiomics features, our XAI system provided transparent insights into decision-making, bridging AI predictions with clinically meaningful NICE grades. To support feature-level association analysis and improve the system’s explainability, we applied a 1–5 scoring scale to the original NICE classification. This continuous scale allowed for capturing subtle variations in polyp characteristics that may be overlooked in binary or categorical labeling. Such granularity is also essential for regression-based modeling, enabling the prediction of nuanced differences between polyp types.

While Dataset A contained an imbalanced AD: HP ratio (approximately 3.5:1), it provided a large volume of data that allowed the model to generalize well without significant bias. Dataset B (used for training based on NICE scores) was intentionally balanced (AD: HP = 1:1) to ensure fair learning during feature-level analysis. In contrast, Dataset C (used for evaluation) was constructed to reflect the real-world clinical distribution of polyps, with approximately 60% AD and 40% HP. Importantly, the model’s predictions on Dataset C demonstrated stable and unbiased performance, supporting the validity of our evaluation approach.

Unlike radiomics, which offers over 30 curated features, color features lack a similar selection process. Their application was limited due to practical issues: polyp images may show subtle color variations based on imaging angles and individual differences, particularly in the background mucosa. Additionally, among the three image-enhanced endoscopic classification systems (NICE, Blue-light imaging Adenoma Serrated International Classification, and Japan NBI Expert Team), the relevance of color features is relatively low. Our approach aligns with recent trends in optical diagnostic tools, many of which exclude color features due to their limited clinical significance7,23. Correlations between radiomics features and deep features enhance the model’s interpretability, directly linking the model’s behavior with visual patterns that clinicians recognize in endoscopic images. By correlating with texture uniformity and structural heterogeneity observed during actual endoscopic procedures, the model aligns with the visual cues clinicians rely on for accurate diagnosis. In this way, radiomics-guided interpretation acts as a conceptual bridge between AI-generated outputs and clinical reasoning. This transparency improves the understanding of the model’s decision-making process, making the AI system more interpretable and clinically useful, and ultimately enhancing clinician trust and utility.

Figure 2 illustrates the feature selection process for implementing XAI, highlighting key deep features associated with each NICE category. For example, feature “215” was linked to surface Type 1, while “702” contributed to vessel Type 2 prediction. Feature “456” influenced both surface and vessel predictions, mainly for Type 1. These results emphasize the value of selecting specific deep features for niceAI design. Table 2 summarizes the diagnostic performances of the ML, DL, and niceAI models. The ML model showed suboptimal performance (AUROC < 0.900, ACC < 0.850), reflecting the limited clinical utility of radiomics despite its interpretability. The DL model achieved higher accuracy (AUROC 0.956, ACC 0.877), but lacked transparency. In contrast, niceAI matched the DL model’s performance while offering interpretability by leveraging intermediate features. This slight trade-off in performance is acceptable, considering the added explainability. Figure 3; Table 3 further demonstrate the clinical potential of niceAI, which met or exceeded SODA and PIVI (NPV) benchmarks and showed comparable or superior results to clinicians. It also exhibited a stronger correlation with NICE grading.

While niceAI performs slightly worse than traditional deep learning models in terms of AUC (0.946 vs. 0.956), the DeLong test showed no statistically significant difference (p-value > 0.05), and the overall accuracy of niceAI was slightly higher. This slight performance trade-off is acceptable in the context of clinical applicability, where the interpretability of the model plays a critical role. The transparency offered by niceAI enhances clinician trust, supports secondary reading, and facilitates its adoption into clinical workflows, which are crucial for improving real-world clinical outcomes. When compared with a recent vision transformer (ViT) model known for its strong performance24niceAI achieved a higher AUC (0.946 vs. 0.936), although the difference was not statistically significant. This slightly lower performance of ViT may be attributed to its high data requirements, as ViT architectures typically require larger sample sizes to fully leverage their representation capacity.

Table 4 analyzes the interpretable values of radiomics features for each NICE category, highlighting how different features contribute to the niceAI system. For Types 1 and 2 of the surface pattern, “Original_glrlm_RunPercentage,” which relates to texture uniformity, showed the most significant influence. The opposing effects of this feature in Types 1 and 2 suggest that the model is distinguishing between surface patterns typically seen in HP and AD, with repetitive, uniform patterns in HP and irregular, heterogeneous patterns in AD. This aligns closely with visual cues observed during endoscopy, where clinicians distinguish between the smooth, repetitive surface patterns of HP and the more complex, irregular textures of AD, as shown in previous studies25,26,27. For vessel Type 1, “original_glcm_Imc1” showed a strong correlation, indicating a higher likelihood of classification as AD. This feature captures large, paired pixel values in a consistent pattern, which mirrors the vascular patterns often associated with adenomatous growths in clinical practice. Such direct associations between deep features and clinically interpretable radiomics characteristics help clinicians understand how the AI model forms its predictions.

However, several study limitations must be addressed in future research. Frist, representations of surface patterns and vessel information were similar, with most DL layers and radiomics features consistent, except for a few. This suggests that the selected radiomics may not effectively distinguish between surface patterns and vessel characteristics. Each clinician may have different diagnostic patterns; however, to maintain interpretability and consistency within our niceAI system, we did not assign weight to each NICE category. NICE grading includes color, this study focused solely on deep features related to texture-based surface patterns and vessel information.

Second, while the additional use of a 1–5 scoring scale based on the NICE classification improved granularity and allowed for regression-based explainability, this modification has not been widely validated. Future studies are warranted to further assess its clinical applicability and generalizability. Third, multiple correlation analyses were performed without correction for multiple comparisons. Since the analysis was exploratory and aimed at improving interpretability rather than formal inference, correction was not applied. However, this may increase the risk of Type I errors. Future studies should consider applying correction methods such as the false discovery rate or Bonferroni adjustment when drawing inferential conclusions.

To reduce label noise and ensure reliable learning, we included only cases where expert optical diagnoses met the PIVI threshold and matched pathology results. While this approach ensured label consistency, it may have introduced selection bias by excluding diagnostically ambiguous cases. However, this was necessary because 15–20% of colorectal polyps are pathologically misclassified, and such errors could undermine the reliability and explainability of the XAI system28,29. As our goal was to develop a trustworthy assistive tool based on the NICE classification, training on clean and reliable data was essential to preserve interpretability.

Another key limitation is the lack of direct comparisons with clinicians or subjective feedback from endoscopists. Instead, we assessed interpretability and clinical alignment by analyzing correlations between model-predicted NICE scores and those from three experienced endoscopists (Table 3). While these results suggest clinical relevance, they do not replace real-world validation. Future studies should assess performance in clinical workflows, including direct comparisons and evaluations of usability and acceptance.

Although the model meets SODA and PIVI thresholds, its imperfect performance has important clinical implications—especially for decisions like leaving or resecting a polyp based solely on optical diagnosis. Thus, niceAI should support, not replace, clinical judgment. Even with benchmark-level performance, the real-world impact of explainable AI on endoscopist decision-making remains unproven. Future studies should evaluate whether explainable CADx systems offer added diagnostic value over conventional models, particularly in borderline cases, and explore strategies such as confidence calibration and expert feedback integration for safe deployment.

While there are existing approaches to radiomics-guided DL feature interpretation30,31 we uniquely integrated deep feature extraction with the NICE classification to ensure clinically meaningful and interpretable outputs. To preserve the spatial complexity of DL features, we applied a two-step correlation approach: Spearman’s rank correlation to identify relevant radiomics-linked features, followed by regression analysis to explore linear relationships. Integrating XAI with the NICE system advances clinical AI by enhancing transparency and trust. Interpretable features enable clinicians to understand and evaluate predictions, supporting error detection and improving reliability. Incorporating clinician feedback will further strengthen the clinical relevance and robustness of such systems. Our study advances the limited research on XAI systems by elucidating the layers of an AI model and offering explanatory insights. By demystifying AI decision-making, niceAI can boost trust, understanding, and acceptance among clinicians, enhancing its practical application in clinical settings. Addressing these limitations and integrating clinician feedback will further enhance the robustness and clinical relevance of XAI systems, benefiting both patients and healthcare professionals.

Methods

Data collection

The study protocol followed the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) Institutional Review Board (H-2311-049-1482). A retrospective dataset was created by extracting polyp images from the Gangnam-Real-Time Optical Diagnosis program8. Prospective datasets, including polyp videos and still images, were collected from January 2020 to December 2021 at the SNUH Healthcare System Gangnam Center, with written informed consent from all patients. All colonoscopies were performed using a high-definition colonoscope (EVIS LUCERA CV 260SL/CV290SL; Olympus Medical System Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

To minimize potential errors (up to 10%) in the pathological interpretation of diminutive polyps32, the training dataset included only cases where expert endoscopists’ optical diagnoses met PIVI thresholds and matched pathological determinations. For small and large polyps, images were obtained through the pathological assessment of small and large polyps.

Model development utilized 7,068 polyps, including 5,492 AD and 1,576 HP (Dataset A), for large-scale supervised training of the deep learning model. Dataset A provided a diverse set of images to ensure the model learned from a wide variety of polyp types. To construct the XAI system based on the NICE classification, Dataset B included 240 polyps (120 AD and 120 HP), selected through a labor-intensive process in which three experienced endoscopists manually assigned quantitative NICE scores. High-resolution images were used to enable reliable NICE assessment, though the sample size was limited due to the manual scoring process. Dataset C, consisting of 300 polyps (160 AD and 140 HP), was used as an independent test set. Collected from July to December 2021, it was temporally separated from the training data to assess the model’s generalizability and real-world applicability. A sample size of 300 polyps is considered reasonable, as it is comparable to those used in previous optical diagnosis studies involving AI-based polyp classification33,34.

NICE grading

Datasets B and C were labeled with the NICE grading by three 7-, 14-, and 20-year experienced endoscopists (Supplementary Table S4)35. To develop a clinically relevant XAI system, endoscopists examined surface, vessel, and color patterns for each type of polyp (NICE Type 1 and 2) and graded patterns from 1 to 5 points to use more divided scores for training accurate regression36,37.

Importantly, the NICE evaluation was conducted based on a pre-established consensus among the endoscopists. Inter-expert agreement was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and Kendall’s tau coefficient, which were found to be 0.841 ± 0.106 and 0.758 ± 0.110, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). This high level of agreement supports the reliability of the NICE grading used for model development and ensures that the feature selection process aligns with clinical judgment. Given that endoscopists who meet both SODA and PIVI criteria are rare, recruiting such objectively validated experts poses practical challenges. This further underscores the value of the consensus-based evaluation in this study8,35.

Building up NiceAI (XAI with NICE grading)

Our method encompassed four key steps (Fig. 1.). (1) extraction of interpretable and noninterpretable features, (2) correlation analysis between these features, (3) identification of features strongly correlated with selected noninterpretable features using NICE grading, and (4) polyp classification and interpretation.

Interpretable radiomics feature extraction

Mask region suggestion

To extract interpretable features within the specific region of each polyp, we utilized Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM)21which highlights important image regions for classification decisions. In our approach, Grad-CAM was applied within the expert-defined polyp bounding box to localize sub-regions that contributed most to the prediction. These high-activation areas were then used as surrogate masks for feature extraction, replacing the need for explicit segmentation. By focusing on Grad-CAM-indicated regions, we improved the ACC and relevance of the radiomics features in our XAI system.

Radiomics feature

Radiomics features are quantitative features widely used in the field of computed tomography analysis owing to the possibility of explainability38. Radiomics features were extracted using the pyRadiomics library (ver 3.0.1, https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io)39.

The extraction process was designed to capture key characteristics of polyps—texture, shape, and intensity—critical for distinguishing between types. First-order statistics and texture features (e.g., contrast, correlation, entropy) quantify surface patterns, with higher entropy and contrast often seen in invasive polyps. Shape features such as surface area and compactness describe geometry, helping differentiate flat vs. protruding and benign vs. malignant forms. Malignant polyps tend to show irregular textures, larger areas, and complex structures, unlike the more regular patterns of benign ones. Full feature details are listed in Supplementary Table S6.

Color features

We computed the mean, skewness, and variation for each red, green, and blue color channel and hue, saturation, and value color space and quantified the brownness of the polyp region by calculating the cosine similarity and Euclidean distance between the polyp and background regions (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Noninterpretable deep feature extraction

ResNet-5040 served as the backbone, featuring convolution layers, a global average pooling layer, and fully connected layers. To enhance interpretability, the focus was on the outputs of convolution layers, which are known for encoding visual information. Deep features extracted via max pooling from these outputs were incorporated to explore relationships within explainable features. Polyp regions labeled by experts were cropped using bounding boxes and padded to maintain aspect ratios before resizing to 150 × 150 pixels. The model was trained with a batch size of 64 for up to 1,000 epochs using the Adam optimizer and cross-entropy loss. The learning rate was optimized using a cosine annealing scheduler to gradually reduce the learning rate, facilitating smooth convergence. The base learning rate and weight decay were both set to 1e-5. To prevent overfitting, early stopping was applied, terminating training if the validation loss did not improve for 5 consecutive epochs. All DL implementations were conducted using PyTorch (ver 1.10.1, https://pytorch.org) and Python 3.10 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA, https://www.python.org)41.

Imposing explainability

Summary

To reduce the dimensionality of the deep features and connect deep and radiomics features, a multi-step feature selection process was employed. This process involved three key steps: (1) correlation analysis (first selection), (2) 100 iterations of regression fitting with random split validation (second selection), and (3) filtering based on feature selection frequency across iterations (third selection). The 100 iterations were crucial in reducing overfitting and identifying stable features. Repeated regression fitting across multiple random splits allowed us to select features that were consistent and less prone to overfitting.

Correlation between noninterpretable and interpretable features (first selection)

Interpretable features were used to indirectly comprehend noninterpretable features. Deep features were selected based on a high Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient with any radiomics feature (> 0.5 or <−0.5, p< 0.05)42. Correlations with an absolute value greater than 0.5 indicate a substantial relationship, which aligns with common practices in medical research for identifying significant associations43. This threshold allows for identifying key relationships that contribute to the model’s interpretability while ensuring that features selected are both relevant and stable. Additionally, their relationships with the radiomics features were analyzed using regression coefficients for further explainability.

Regression between noninterpretable and NICE features grading (second and third selection)

Combinations of deep features that could best regress each NICE feature grade were chosen44.

-

1)

Dataset split: Dataset B was bifurcated into two distinct groups.

-

2)

Regression fitting: Utilizing the initial group of 120 polyps, regression fitting was conducted.

-

3)

Feature validation and scoring: For the subsequent set of 120 polyps, the coefficient of determination (R2 score) was computed for each deep feature within each NICE category. The categories evaluated included: surface pattern Type 1, surface pattern Type 2, vessel Type 1, and vessel Type 2.

-

4)

Feature ranking: Within each category, the top 10 deep features were identified based on their respective regression R2 scores, highlighting their predictive power.

-

5)

Iteration of process: Steps 1 through 4 were iteratively performed 100 times to validate the consistency and reliability of the selected features with different random seeds (second selection).

-

6)

Final feature selection: Ultimately, deep features were ranked according to the frequency of their selection across iterations, determining their prominence and utility in the model (third selection).

The optimal deep feature combination for each NICE category was identified by iteratively adding features in the second selection order, comparing the highest R2 value for each combination, and repeating the process thrice with Dataset B. The combination yielding the highest average R2 score was selected for each NICE. The R2 score was used because it provides a normalized measure of how well the model explains the variance in the data, allowing for effective comparison of feature combinations. To ensure stability and robustness across different data split, the R2 score was calculated using 3-fold cross-validation.

Diagnosis of NiceAI

In niceAI, the diagnosis involves calculating the difference between the predicted Type 1 and Type 2 scores, each ranging from 0 to 5. HP is diagnosed if the Type 1 score exceeds the Type 2 score, and AD is diagnosed if the Type 2 score is higher than Type 1. After considering both surface and vessel information, the final diagnosis is determined as the average of these two categories (Supplementary Fig. S4). For the comparison between different models, a single probability score was derived by computing the difference between the predicted Type 2 and Type 1 scores using the formula (1). This continuous probability value enabled consistent comparisons between models such as the DeLong test.

NiceAI performance evaluation

Using Dataset C, the performance of the system was evaluated in two ways. First, we assessed the polyp classification of niceAI by measuring the AUROC, ACC, SEN, SPE, PPV, and NPV. We also compared the performance of niceAI with that of ResNet-50 AI and ViT by using DeLong’s test. Second, we analyzed the correlation coefficient between clinician-evaluated NICE grading and NICE prediction output of niceAI using Spearman’s and Kendall tau rank.

Additional explanation of NiceAI

niceAI involves two main steps: mapping radiomics to deep features and then to NICE grading. Initially, the regression coefficient between radiomics and deep features is extracted. Subsequently, the regression coefficient between deep features and NICE grading is calculated. Multiplying these coefficients results in interpretable values, elucidating the influence of radiomics features on niceAI.

Data availability

The data, analytic methods, and study materials used in this study will be made available to other researchers upon reasonable request. Researchers interested in accessing these materials (including code) should contact the corresponding author for further information and conditions.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21763 (2023).

Patel, S. G. et al. Cost effectiveness analysis evaluating real-time characterization of diminutive colorectal polyp histology using narrow band imaging (NBI). J. Gastroenterol. Sci. 1(1), 1–15 (2020).

Rex, D. K. et al. The American society for Gastrointestinal endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and incorporation of valuable endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest. Endosc. 73, 419–422 (2011).

Abu Dayyeh, B. K. et al. ASGE technology committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81, 502. .e501-502.e516 (2015).

Houwen, B. et al. Definition of competence standards for optical diagnosis of diminutive colorectal polyps: European society of Gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) position statement. Endoscopy 54, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1689-5130 (2022).

Hewett, D. G. et al. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology 143, 599–607 (2012).

Bisschops, R. et al. BASIC (BLI adenoma serrated international Classification) classification for colorectal polyp characterization with blue light imaging. Endoscopy 50, 211–220 (2018).

Bae, J. H. et al. Improved Real-Time optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps following a comprehensive training program. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 2479–2488e2474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.019 (2019).

Bang, C. S., Lee, J. J. & Baik, G. H. Computer-Aided diagnosis of diminutive colorectal polyps in endoscopic images: systematic review and Meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e29682. https://doi.org/10.2196/29682 (2021).

Krenzer, A. et al. A real-time polyp-detection system with clinical application in colonoscopy using deep convolutional neural networks. J. Imaging. 9, 26 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Real-time gastric polyp detection using convolutional neural networks. PloS One. 14, e0214133 (2019).

Barua, I. et al. Real-time artificial intelligence–based optical diagnosis of neoplastic polyps during colonoscopy. NEJM Evid. 1, EVIDoa2200003 (2022).

Rondonotti, E. et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted optical diagnosis for the resect-and-discard strategy in clinical practice: the artificial intelligence BLI characterization (ABC) study. Endoscopy 55, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1852-0330 (2023).

Li, J. W. et al. Real-World validation of a Computer-Aided diagnosis system for prediction of polyp histology in colonoscopy: A prospective multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002282 (2023).

Fitting, D. et al. A video based benchmark data set (ENDOTEST) to evaluate computer-aided polyp detection systems. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 57, 1397–1403 (2022).

Xu, Q. et al. Interpretability of Clinical Decision Support Systems Based on Artificial Intelligence from Technological and Medical Perspective: A Systematic Review. Journal of Healthcare Engineering (2023). (2023).

Eisenmann, M. et al. Biomedical image analysis competitions: The state of current participation practice. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.08568 (2022).

Dong, Z. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence incorporated with domain knowledge diagnosing early gastric neoplasms under white light endoscopy. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 64 (2023).

Misawa, M. et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted polyp detection for colonoscopy: initial experience. Gastroenterology 154, 2027–2029 (2018). e2023.

Zhou, B., Khosla, A., Lapedriza, A., Oliva, A. & Torralba, A. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2921–2929.

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 618–626.

Zhang, Y. et al. Grad-CAM helps interpret the deep learning models trained to classify multiple sclerosis types using clinical brain magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurosci. Methods. 353, 109098 (2021).

Sano, Y. et al. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI expert team. Dig. Endoscopy. 28, 526–533 (2016).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:.11929 (2020). (2020). (2010).

Doğan, R. S., Akay, E., Doğan, S. & Yılmaz, B. Hyperplastic and tubular polyp classification using machine learning and feature selection. Intelligence-Based Med. 10, 100177 (2024).

Sánchez-Montes, C. et al. Computer-aided prediction of polyp histology on white light colonoscopy using surface pattern analysis. Endoscopy 51, 261–265 (2019).

Mesejo, P. et al. Computer-aided classification of Gastrointestinal lesions in regular colonoscopy. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 35, 2051–2063 (2016).

Ahmad, A. et al. Implementation of optical diagnosis with a resect and discard strategy in clinical practice: DISCARD3 study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 96, 1021–1032 (2022). e1022.

Djinbachian, R. et al. Using computer-aided optical diagnosis and expert review to evaluate colorectal polyps diagnosed as normal mucosa in pathology. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22(11), 2344–2346.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2024.03.041 (2024).

Paul, R. et al. Explaining deep features using radiologist-defined semantic features and traditional quantitative features. Tomography 5, 192–200 (2019).

Cho, H. et al. Radiomics-guided deep neural networks stratify lung adenocarcinoma prognosis from CT scans. Commun. Biology. 4, 1286 (2021).

Cross, S. S. et al. What levels of agreement can be expected between histopathologists assigning cases to discrete nominal categories? A study of the diagnosis of hyperplastic and adenomatous colorectal polyps. Mod. Pathol. 13, 941–944 (2000).

Jin, E. H. et al. Improved accuracy in optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps using convolutional neural networks with visual explanations. Gastroenterology 158, 2169–2179. e2168 (2020).

Patino-Barrientos, S., Sierra-Sosa, D., Garcia-Zapirain, B., Castillo-Olea, C. & Elmaghraby, A. Kudo’s classification for colon polyps assessment using a deep learning approach. Appl. Sci. 10, 501 (2020).

Kim, J. et al. Impact of 3-second rule for high confidence assignment on the performance of endoscopists for the real-time optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps. Endoscopy https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2073-3411 (2023).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction To Statistical LearningVol. 112 (Springer, 2013).

Lambin, P. et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer. 48, 441–446 (2012).

Van Griethuysen, J. J. et al. Computational radiomics system to Decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 77, e104–e107 (2017).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 770–778.

Paszke, A. et al. Automatic differentiation in pytorch. (2017).

Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. (1961).

Rovetta, A. Raiders of the lost correlation: a guide on using pearson and spearman coefficients to detect hidden correlations in medical sciences. Cureus 12(11), e11794. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.11794 (2020).

Draper, N. R. & Smith, H. Applied Regression AnalysisVol. 326 (Wiley, 1998).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to AINEX corporation for providing the dataset used in this study. Their support and contribution have been invaluable to the success of this research.

Funding

This research was supported by grant no 03-2022-2180 from the Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) Research Fund and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00356090). The funding source did not have any direct involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or the writing of this report. The authors conducted the research independently, and the decision to submit this report for publication was made by the research team.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS: Analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, interpretation of data, and drafting. JHB: conception and design of the study, funding acquisition, drafting and revision. JK: Data curation, resources, validation, and interpretation of data. JC: Review and editing of the manuscript, critical revision of content, and providing feedback on the manuscript’s scientific accuracy.Y-GK: conception and design of the study and revision of the manuscriptAll authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, thereby ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. No other professional writers were employed.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, Y., Bae, J.H., Kim, J. et al. A novel approach to overcome black box of AI for optical diagnosis in colonoscopy. Sci Rep 15, 21220 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04770-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04770-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A comparative study of artificial intelligence-based approaches for colorectal cancer diagnosis

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)