Abstract

A recent systematic review found that education programs in perinatal mental health (PMH) had limited effects on detection, referral, and support of parents with perinatal mental health problems. This participative qualitative study (i.e. co-production by academic researchers and researchers with lived experience as equal partners) sought to explore the experiences, views and priorities of persons with lived experience (PWLEs), obstetric providers, childcare health providers and mental health providers (MHPs) on education in PMH. We conducted nine focus groups and 24 individual interviews (n = 84 participants: 24 PWLEs; 30 obstetric providers; 11 childcare health providers and 19 MHPs). We used Braun & Clarke’s inductive six-step process in the thematic analysis. We found some degree of difference in the priorities for education in PMH identified by PWLEs (e.g. person-centred collaborative perinatal healthcare) and providers (e.g. knowledge about perinatal mental health problems). Providers considered PMH assessment as part of their role (except for parents with suicidal ideations or serious mental illness) but reported feeling ill-prepared to do so. Organisational factors comprised PMH integration into standard perinatal healthcare and common culture between non-MHPs and MHPs. Education programs in PMH should be co-designed with PWLEs and focus on providing collaborative person-centred care for all parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perinatal Mental Health Problems (PMHPs) - herein we will use this term to refer to perinatal psychiatric disorders in accordance with the preferences of persons with lived experience - commonly consist of anxiety, non-psychotic depressive episode, psychotic episodes, post-traumatic stress disorder and adjustment disorder during pregnancy and the 1st year postpartum. PMHPs remain predominantly unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated1.

Given their role in perinatal care providing multiple occasions to discuss perinatal mental health (PMH), obstetric providers are key stakeholders to improve perinatal mental health care (PMHC). The International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) (2024)2 consider postpartum mental health assessment and the detection, referral, and support of parents with PMHPs as Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice (ECMP). Despite parents’ preferences for discussing PMH with obstetric providers than mental health providers (MHPs), obstetric providers often report feeling less comfortable with opening conversations about PMH compared with assessing and managing physical health and consider their role into PMHC as unclear3,4,5,6,7,8.

Extending the results of previous reviews on obstetric providers’ educational needs in PMH and related interventions9,10,11, a recent systematic review found that understanding of each other’s role into PMHC and the intention to participate in PMHC are influential for the effective translation of PMH related competencies into clinical practice, above and beyond knowledge, skills, and confidence8.

There remain some limitations to the current body of evidence. First, despite figuring into the ICM standards for global midwifery education (2024 )2 and calls to improve providers’ education in PMH4,6,9,11, education in PMH is highly variable across studies (e.g. suicide risk assessment is the least covered topic in education interventions on PMH8) with limited effects on obstetric providers’ knowledge, skills, detection and referral rates and depressive symptoms. Second, student midwives, midwives, obstetric residents, and even specialist midwives continue reporting feeling ill prepared to care for parents with PMHPs4,8,9. Third, the ECMP focus on postpartum depression, anxiety, and psychosis without covering the antenatal period or the full range of PMHPs2. Fourth, most studies on PMH education came from the United States, Australia, or the United Kingdom and did not include all relevant stakeholders, e.g. persons with lived experience (PWLEs)8,9,11. The quality of the studies included in these reviews remains low to moderate due to the presence of methodological bias and there is to our knowledge no validated curriculum developed for various types of perinatal health providers4,8. Fifth, most studies did not involve researchers with lived experience nor used a participatory design.

According to the Medical Research Council framework for developing complex interventions12, such research should include the meaningful involvement of persons with lived experience and the participation of all other relevant stakeholders. To inform the design of future interventions, this participatory qualitative study sought to explore the experiences, views and priorities of PWLEs and various perinatal health providers on education in PMH.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

The present study is part of a larger study on the improvement of perinatal mental healthcare, described elsewhere13. We used a participatory action research design, i.e. a co-construction approach that promotes a meaningful involvement of PWLEs14. The degree of participation in this study ranged from a consultative level (e.g. individual interviews or focus groups) to a collaborative and empowering level (e.g. integrating a co-researcher with lived experience - the 3rd author - in the research team from the start of the project, who has been involved in the analysis and all key project decisions)15. Other members of the research team comprised clinical researchers specialised in perinatal psychiatry (midwife, child and adolescent (C&A) psychiatrist, adult psychiatrist).

Study design and participants

The present study explored the experiences, views, ideas, expectations and priorities on education in perinatal mental health of (i) persons with lived experience of PMHPs, serious mental illness or autism, (ii) obstetric providers, (iii) childcare health providers, (iv) mental health providers. We combined focus groups for health providers and in-depth individual interviews for persons with lived experience conducted between December 2020 and May 2022. We used the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ16) to design the study protocol and report results. Supp. Material S1 describes the recruitment strategy for the PWLEs and the health providers groups. Eligible participants in the PWLEs group were adults (age > 18) with lived experience of PMHPs (self-identified) or a confirmed diagnosis of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression; DSM-517) or autism spectrum disorder (hereafter referred to as autism; DSM-517). Eligible participants in the health providers’ group were obstetric providers (midwives and obstetricians), childcare health providers (paediatricians, general practitioners, paediatric nurses, childcare assistants) and mental health providers (MHPs; C&A psychiatrists, adult psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health nurses, social workers). They were recruited through three perinatal health networks in the Auvergne Rhône-Alpes region and a group of experts in perinatal mental health (PMH) in the Ile de France region. The relevant Ethical Review Board ("Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP) Ile de France 1"; Legislative Decree 196/03-France) approved the appraisal protocol on March 10, 2020 and all participants gave informed consent. We complied with GDPR and CNIL regulations. This study has been conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (Tokyo 2004, revised) and the French Public Health Law no. 2004-806 of 9 August 2004 concerning research involving the human person, application decree no. 2006-477 of 26/04/2006 amending Chapter I of Title II of Book 1 of Part 1 of the French Public Health Code concerning research involving the human person, as well as the decrees in force.

Procedure

Researchers’ own position, views and opinions can influence the research process18. We used a participatory research design and adopted a reflexive position from the inception of the project to ensure that researchers’ convictions did not dominate the study design or data collection and analysis. To capture the complexity of the topic and to facilitate participants’ expression on sensitive information (i.e. their personal experiences, views, feelings and attitudes19), we conducted in-depth individual interviews for PWLEs and separate focus groups for health providers according to their type of practice (i.e. obstetric providers; childcare health providers; MHPs). Given the pandemic context, most of the individual interviews and focus groups were conducted online using secured video-conferencing solutions. Supp. Material S1 provides details on data collection using focus groups and individual interviews. Participants were asked the same set of questions in the individual interviews and in focus groups (see Supp. Material S2 for the semi-structured interview and general information recorded for PWLEs and health providers). We asked participants about their experiences, views, feelings, and attitudes towards PMHC and the care of perinatal depression. For this study, we made a focus on education needs in PMH. Individual interviews and focus groups were conducted by at least two members of the research team, video and tape recorded and fully transcribed.

Data analysis

For the thematic analysis, we used an inductive, rather than theoretical, approach to qualitatively analyse the data (i.e. “bottom-up” identification of themes20). We followed the six-step process by Braun and Clarke (2006)20 - details are provided in Supp. Material S1. Coder debriefings occurred throughout the analysis to review the identified themes and reach an agreement on coding discrepancies. To allow a deeper and broader understanding of the topic, we used methodological triangulation (i.e. using several types of qualitative approaches, individual interviews and focus groups21), investigator triangulation (i.e. independent coding by two researchers with different backgrounds, a specialist midwife and a perinatal psychiatrist and review of all codes by a 2nd perinatal psychiatrist and a lived experience researcher) and data triangulation (i.e. comparison of the perspective of various stakeholders on a same topic21). Participants did not give their feedback on the results. We obtained code saturation, i.e. the point in the research process where no new information is discovered in data analysis, and meaning saturation, i.e. the point when no further dimensions, nuances, insights of issues can be found20.

Results

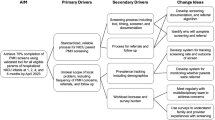

Nine focus groups and 24 individual interviews were conducted (n = 84 participants). The PWLEs group was composed of four women and one man with lived experience of PMHPs, nine women with serious mental illness and ten autistic women. The provider group was composed of 30 obstetric providers (27 midwives, 3 obstetricians), 11 childcare health providers (4 paediatricians, 3 general practitioners, 3 paediatric nurses, 1 childcare assistant) and 19 MHPs (3 child and adolescent psychiatrists, 4 adult psychiatrists, 8 psychologists, 3 MH nurses and 1 social worker). Sample characteristics are presented on Table 1. We identified factors that occurred at different levels: provider, interpersonal and organizational. The results of the qualitative analysis are presented in Figure S1, Tables 2, 3 and 4, and Supplementary Tables S3, S4 and S5 (quotations supporting the themes and subthemes).

Provider and interpersonal level factors

MHPs and PWLEs observed a consumer-driven change in non-MHPs interest in PMHC, mirroring an increased awareness of PMHPs in the general population. However, this often came at a shock for midwives and other non-MHPs (e.g. learning about suicide being one of the leading causes of maternal mortality). A potential explanation is that contrary to obstetric complications occurring rapidly after childbirth (e.g. postpartum haemorrhage), PMHPs and maternal suicide usually occur later in the postpartum, making the topic less concrete / less of personal concern for obstetric providers.

PWLEs and several health providers described PMH and wellbeing as topics health providers should initiate conversations on with all parents. According to many participants, obstetric providers’ place in perinatal healthcare provided many opportunities to open discussions about PMH (e.g. early prenatal and postnatal interviews, routine follow-up visits, childbirth classes or perineal rehabilitation).

Despite considering that PMH assessment is part of their role, perinatal health providers reported to feel ill equipped to provide PMHC. The potential reasons included a lack of knowledge about maternal/paternal PMHPs and a lack of interviewing/distress management skills. Parents and most health providers reported positive attitudes towards opening conversations about PMH and the use of screening tools that were seen as way to reduce stigma. Twelve health providers, especially private practice health providers, described distressing emotional experiences in case of positive answers combined with declined referral to specialised mental health services. Alternatives to formal screening included targeted screening on identified risk factors and behavioral observation, e.g. mother-baby interaction. Compared with midwives, pediatricians reported more negative attitudes towards the use of screening tools and to rely more on behavioral observation.

While no anaesthetist participated in the present study, mothers outlined their potential role in perinatal mental health (e.g. prevention of childbirth trauma). Perinatal health providers’ lack of training in distress management/counselling skills resulted in discomfort in case of positive answer - in particular, when caring for women declining referral. While the position of fathers was mainly envisioned from the perspective of their partner, some PWLEs and non-MHPs described the need to assess fathers’ PMH and to provide them adequate PMHC.

Receiving feedback from MHPs after referrals (e.g. accuracy of detection/referral and information about the positive outcomes achieved through referral) and formal supervisions by MHPs was helpful to improve non-MHPs’ ability to detect and manage PMHPs and their engagement in PMHC (e.g. finding meaning in opening discussions about PMH and being able to reassure women about referral to mental health services). Similarly, perinatal health providers described multidisciplinary work and joint obstetric care as useful resources.

We found some degree of difference between education needs identified by health providers and PWLEs. Several women reported negative experiences of perinatal healthcare (e.g. powerlessness, communication problems, lack of empathy and/or disrespect). PWLEs identified personal recovery and collaborative person-centred care as priorities, whereas the priorities identified by health providers covered knowledge about PMHPs and related skills, e.g. opening discussions about PMH without being intrusive, managing distress in case of a positive answer and discussing referral options. MHPs supported the adoption of a continuum approach of PMH in training interventions.

Contrasting with PMH assessment, midwives considered that caring for women with serious mental illness or suicidal ideations was not part of their role and held stigmatizing attitudes towards this population (e.g. perceived dangerousness for self, others, and the baby). Midwives reported to lack awareness about suicide during the perinatal period and negative attitudes towards suicide risk assessment. Given depression remains often undetected and suicide usually occurs after the end of the follow-up by obstetric providers some participants suggested to raise awareness on these issues (e.g. providing feedback on women who consulted in perinatal psychiatry for PMHPs/suicide ideations). While midwives did not report training needs related to serious mental illness, women with serious mental illness and autistic women reported experienced and anticipated stigma during the interactions with perinatal health providers.

Organizational factors

Organizational factors included dedicated time to assess PMH, dedicated funding, continuity of care, barriers related to language/culture and the presence of clear referral pathways and available specialist mental health services. Non-MHPs called for a better integration between mental health and perinatal health care to reduce stigma (e.g. integrating PMH as a routine aspect of perinatal healthcare) and improve PMHC (e.g. common culture and shared training sessions).

Discussion

Main findings

To our knowledge, this qualitative study is the first integrating the perspective of PWLEs, obstetric providers, childcare health providers, and MHPs on the improvement of education in perinatal mental health using a participatory research design. We identified a wide range of leads to improve education in PMH that included: 1) meeting the specific priorities identified by PWLEs (e.g. person-centred collaborative perinatal healthcare); 2) facilitating a meaningful engagement into perinatal mental healthcare; 3) improving non-MHPs’ knowledge, skills and attitudes about persons with suicide ideations or serious mental illness.

Strengths and limitations

There are limitations. First, our sample was self-selecting (i.e., persons interested in improving PMHC) and cannot be considered as representative of the experience of all stakeholders involved in PMHC. However, the large size (n = 84), the diversity of the sample (i.e., realization in five distinct locations, the inclusion of various PWLEs and inclusion of health providers with diverse backgrounds and practices working in urban, semi-urban and rural areas) and the use of three triangulation methods are considerable strengths. Similarly, the proportion of women was high in all groups and most health providers worked in public hospitals, thereby reducing the generalizability of our findings to men and private practice providers. Of 24 PWLE, 1/4 worked as health providers or social workers. Given the experience of this at-risk population remains under-investigated, this could be a strength. Second, there was an unequal representation of persons with lived experience (n = 24) and healthcare providers (n = 60) in this study, which could have affected the research process and analysis15. However, the large number of participants with lived experience (n = 24) and the integration of a co-researcher with lived experience in the research team as an equal partner may have addressed this limitation. Third, we did not involve student midwives, managers from public hospitals or local/regional public healthcare. Fourth, many individual interviews or focus groups were conducted online because of the pandemic context, which could have affected the quality of data collection. However, in-person and online focus groups yielded comparable themes and online discussions facilitated sharing of in-depth personal stories and discussion of sensitive topics in a recent study22. Fifth, researchers’ own position, views, and opinions can influence the research process18. Similarly, medical dominance, i.e. the asymmetry in relations and power dynamics that could exist in a research team when medical doctors are involved23, can also influence the research process. Adopting a participatory research design and a reflexive position from the inception of the project may have addressed these limitations.

Interpretation

We found many interactions but also some degree of difference in the priorities for education in PMH identified by PWLEs (e.g. person-centred collaborative perinatal healthcare) and non-MHPs (e.g. knowledge about PMHPs). Most provider-identified education needs concur with previous research9,10,11. MHPs supported the adoption of a continuum approach of PMH to reduce stigma, associated with more prosocial reactions in non-perinatal depression24. However, the degree of difference in the priorities identified by PWLEs and non-MHPs is concerning because communication skills and collaborative person-centred care are part of the ECMP2 and have been identified as crucial for PMHPs and perinatal suicide prevention (e.g. by reducing shame and fostering connection25,26,27).

Perinatal health providers in this study had positive attitudes towards PMH assessment but reported feeling ill-equipped to do so - this aligning with previous research8,9,10,11. In addition to factors already described in the literature (e.g. provider level: knowledge/skills; organizational level: clear referral pathways/supervision by MHPs8,28), we found that putting PMH in context in education programs before covering related knowledge or skills, as well as considering organizational factors and subjective factors (e.g. understanding of each other’s role in PMHC, personal interest in PMH and behavioural intent) is crucial to the translation in routine clinical practice.

As reported in the aforementioned systematic review8, midwives in this study had negative attitudes towards their role in suicide risk assessment and suicide prevention and reported stigmatizing attitudes towards parents with suicidal ideation. This is concerning given suicide is the leading cause of maternal mortality in high-income countries29. In a recent systematic review of 100 articles, Groves et al.30 identified that midwives had more mental health problems and were at increased risk of suicide compared with the general population. Staff members’ personal experiences of mental health problems have been associated both with positive (e.g. stigma reduction fostering a sense of connection with the parents) and negative attitudes towards parents with PMHPs8,9. Relatedly, we observed some degree of difference between parents and health providers on education needs related to serious mental illness and autism. In contrast with parents with serious mental illness who reported experienced and anticipated stigma in perinatal healthcare, health providers in this study reported negative attitudes towards their role in PMHC for parents with serious mental illness and did not report related education needs - this aligning with the aforementioned systematic review8.

Conclusion

Practical and research recommendations

Our findings support the need to promote a meaningful engagement of PWLEs to inform education interventions in PMH - this aligning with the MRC framework for designing complex interventions12. Education programs for perinatal health providers should therefore make an explicit focus on meeting the priorities identified by PWLEs, e.g. “collaborate with women in developing a comprehensive plan of care that respects her preferences and decisions”2,25, to improve perinatal healthcare experiences for all parents.

Participants in this study formulated several recommendations for a meaningful engagement into PMHC: 1) integrating PMH into standard perinatal healthcare; 2) developing a common culture between non-MHPs and MHPs and understanding each provider’s role in PMHC (e.g. shared training sessions); 3) adopting continuum approach of PMH and covering personal recovery and the positive outcomes that could be achieved through timely detection and referral; 4) improving interviewing and distress management skills. This concurs with the findings of the aforementioned systematic review8 and the literature about stigma reduction in non-perinatal depression24.

Professional negative experiences (e.g. undetected depression, maternal suicide during pregnancy, learning about avoidable deaths by suicide) influenced non-MHPs’ engagement into PMHC. Given personal burnout and job-related stress can have a negative impact on health providers and midwives’ mental health30, education in PMH should include prevention strategies for coping with the emotional distress that could come with positive screenings.

Despite recommendations for a universal screening for perinatal depression in some international guidelines31, suicide risk assessment does not figure in the ECMP2. Some PWLEs and non-MHPs in this study reported the need to assess PMH in fathers, which aligns with some research32 but is not part of the ECMP2. Given midwives are at increased suicide risk30 but report negative attitudes towards parents with suicidal ideation, covering suicide prevention in education programs in PMH could be crucial to improve service users and providers outcomes. Education programs should cover PMH in fathers, in parents with serious mental illness and in autistic parents to improve their perinatal healthcare experiences.

To conclude, improving education in PMH is a complex intervention that requires integrating the perspectives of all relevant stakeholders including persons with lived experience. Education programs should focus on providing collaborative person-centred care for all parents and the development of a common culture in PMH.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Howard, L. M. & Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 19(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20769 (2020).

Confederation of Midwives (ICM) Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice. (2024). https://internationalmidwives.org/wp-content/uploads/EN_ICM-Essential-Competencies-for-Midwifery-Practice-1.pdf

Williams, C. J., Turner, K. M., Burns, A., Evans, J. & Bennert, K. Midwives and women’s views on using UK recommended depression case finding questions in antenatal care. Midwifery 35, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.01.015 (2016).

Hutner, L. A. et al. Cultivating mental health education in obstetrics and gynecology: A call to action. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 3(6), 100459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100459 (2021).

Rothera, I. & Oates, M. Managing perinatal mental health: A survey of practitioners’ views. Br. J. Midwifery. 19(5), 04–313 (2011).

Coates, D. & Foureur, M. The role and competence of midwives in supporting women with mental health concerns during the perinatal period: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community. 27(4), e389–e405. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12740 (2019).

Wang, T. H., Pai, L. W., Tzeng, Y. L., Yeh, T. P. & Teng, Y. K. Effectiveness of nurses and midwives-led psychological interventions on reducing depression symptoms in the perinatal period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs. Open. 8(5), 2117–2130. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.764 (2021).

Dubreucq, M. et al. A systematic review of midwives’ training needs in perinatal mental health and related interventions. Front. Psychiatry. 15, 1345738. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1345738 (2024).

Noonan, M., Doody, O., Jomeen, J. & Galvin, R. Midwives’ perceptions and experiences of caring for women who experience perinatal mental health problems: An integrative review. Midwifery 45, 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.12.010 (2017).

Legere, L. E. et al. Approaches to health-care provider education and professional development in perinatal depression: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 17(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1431-4 (2017).

Branquinho, M., Shakeel, N., Horsch, A. & Fonseca, A. Frontline health professionals’ perinatal depression literacy: A systematic review. Midwifery 111, 103365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103365 (2022).

Skivington, K. et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061 (2021).

Dubreucq, M. et al. Toward recovery-oriented perinatal healthcare: A participatory qualitative exploration of persons with lived experience and health providers’ views and experiences. Eur. Psychiatry. 66(1), e86. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2464 (2023).

Cornish, F. et al. Participatory action research. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers. 3, 34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-023-00214-1 (2023).

Vaughn, L. M., & Jacquez, F. (2020) Participatory research methods—Choice points in the research process. J. Participatory Res. Methods. https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 (2007).

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5), 5th ed. (American Psychiatric Press, 2013)

Finlay, L. “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual. Health Res. 12(4), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973202129120052 (2002).

Kruger, L. J., Rodgers, R. F., Long, S. J. & Lowy, A. S. Individual interviews or focus groups? Interview format and women’s self-disclosure. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 22(3), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1518857 (2019).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3(2), 77–101 (2006).

Farmer, T., Robinson, K., Elliott, S. J. & Eyles, J. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual. Health Res. 16(3), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285708 (2006).

Woodyatt, C. R., Finneran, C. A. & Stephenson, R. In-person versus online focus group discussions: A comparative analysis of data quality. Qual. Health Res. 26(6), 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316631510 (2016).

Bueter, A., Jukola, S. Multi-professional healthcare teams, medical dominance, and institutional epistemic injustice. Med. Health Care Philos. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-025-10252-z.

Peter, L. J. et al. Continuum beliefs and mental illness stigma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlation and intervention studies. Psychol. Med. 51(5), 716–726. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000854 (2021).

Biggs, L. J. et al. Pathways, contexts, and voices of shame and compassion: A grounded theory of the evolution of perinatal suicidality. Qual. Health Res. 33(6), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323231164278 (2023).

Leavy, E. et al. Disrespect during childbirth and postpartum mental health: A French cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05551-3 (2023).

Andersen, C. G., Thomsen, L. L. H., Gram, P., Overgaard, C. ‘It’s about developing a trustful relationship’: A Realist Evaluation of midwives’ relational competencies and confidence in a Danish antenatal psychosocial assessment programme. Midwifery. 122, 103675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2023.103675 (2023)

Webb, R. et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social care settings: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 8(6), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30467-3 (2021).

Les morts maternelles en France : mieux comprendre pour mieux prévenir. 7e rapport de l’Enquête nationale confidentielle sur les morts maternelles (ENCMM), 2016–2018. Saint-Maurice : Santé publique France. (2024). 232 p. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-cardiovasculaires-et-accident-vasculaire-cerebral/maladies-vasculaires-de-la-grossesse/documents/enquetes-etudes/les-morts-maternelles-en-france-mieux-comprendre-pour-mieux-prevenir.-7e-rapport-de-l-enquete-nationale-confidentielle-sur-les-morts-maternelle

Groves, S., Lascelles, K. & Hawton, K. Suicide, self-harm, and suicide ideation in nurses and midwives: A systematic review of prevalence, contributory factors, and interventions. J. Affect. Disord. 331, 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.03.027 (2023).

RISE-UP PPD. Evidence-based practice guidelines for prevention, screening and treatment of peripartum depression. (2023). https://www.riseupppd18138.com/uploads/2/6/9/7/26978228/riseupppd_clinicalpracticeguidelines.pdf

Darwin, Z. et al. Assessing the mental health of fathers, other co-parents, and partners in the perinatal period: mixed methods evidence synthesis. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 585479. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585479 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to women, men and health providers who participated in this research and who shared their times, experiences and ideas. We thank the FondaMental Foundation (www.fondationfondamental.org), which is a non-profit foundation supporting research in psychiatry in France. We would like to thank Mrs Aurélie Delmas (perinatal health network ELENA), Mrs Mathilde Dublineau (Naître et Bien-Être network) and Mr Laurent Gaucher (midwife and researcher) who participated in the early stages of the study and data collection. We would like to thank Pr Céline Chauleur, Dr Tiphaine Barjat, Dr Laure-Élie Digonnet, Pr Cyril Huissoud, Pr Pascal Gaucherand, Pr Denis Gallot, Dr Amélie Delebaere (obstetricians), Mrs Stephanie Weiss (midwife) and Dr Catherine Salinier (French association of outpatient pediatrics) for their support to this project. We are also grateful to the reviewers of a previous version of the manuscript for their helpful comments.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the APICIL Foundation, the LEEM foundation and the MUSTELA foundations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD and MD initiated and coordinated the project. MD, MT, ST and JD made the qualitative analysis. MD drafted the manuscript. MD and JD the literature review. CM, CD, PF and ML were involved in data collection and critically revised the article. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The relevant Ethical Review Board (CPP-Ile de France I) approved the appraisal protocol on March 10, 2020 and all participants gave informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dubreucq, M., Dupont, C., Thiollier, M. et al. Improving education in perinatal mental health, a participatory qualitative analysis. Sci Rep 15, 21836 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04781-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04781-z