Abstract

The biokinetic and dosimetry models recommended by the International Commission on Radiological Protection do not incorporate dosimetric uncertainty. Recently, Bayesian approach—offering distribution of dose estimates rather than a single point value—has been applied in epidemiological risk modeling. Although the true dose is unknown, Bayesian analysis is assumed to provide information on the true dose through a posterior distribution. This study presents a unique opportunity to validate that assumption. Radiation dose is directly related to the time-dependent radionuclide activity deposited or retained in organs and tissues. Therefore, uncertainties in organ activity predictions derived from biokinetic modeling can serve as proxies for the uncertainties in dose estimation. In this study, uncertainties in model predictions of 239Pu organ activities were evaluated for 20 former nuclear workers with known plutonium inhalation. Ten individuals from Los Alamos were primarily exposed to soluble Pu-nitrate, while ten from Rocky Flats were exposed to insoluble PuO2. All individuals were volunteer tissue donors to the United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries. Urine bioassay data and post-mortem measurements of 239Pu in the liver, skeleton and respiratory tract were used in the analysis. Latin hypercube sampling was employed to generate parameter sets for each realization, varying only two parameters of the human respiratory tract model: the rapidly dissolved fraction, fr and slow dissolution rate, ss. For each realization: (i) intake was estimated using maximum likelihood fitting of the urine bioassay data, and (ii) post-mortem organ activities, used as surrogates of true doses, were predicted based on the estimated intake. Predicted distributions of 239Pu organ activities were compared to point estimates based on default parameters for soluble and insoluble plutonium, as well as to the measured post-mortem values. Results showed that in most cases, the predicted distributions did not cover the measured values (75% for liver, 90% for skeleton, and 50% for the respiratory tract), indicating a need to improve current biokinetic models. Additionally, in some cases, the model predictions were not conservative, which raises concerns from a radiation protection standpoint.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To estimate health risks of exposure to ionizing radiation, epidemiological studies generally rely on the radiation dosimetry system recommended by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP)1. Radiation doses delivered to sensitive organs/tissues from incorporated radionuclides are usually inferred using the appropriate mathematical models referred to as biokinetic models applied to relevant measurement data. The currently recommended biokinetic models for internal dosimetry of workers are described in the ICRP Occupational Intakes of Radionuclides (OIR) series of publications2,3,4,5,6. These models are primarily designed for practical applications in radiological protection, such as ensuring compliance with dose limits in occupational exposure scenarios. For epidemiological studies, however, it is advisable, where feasible, to perform case- or cohort-specific dose assessments. Such assessments may rely on ICRP reference models, appropriately adapted to reflect the specific characteristics of the study population. The primary source of information for dose assessment in radiation epidemiological studies of nuclear workers is bioassay monitoring data, such as urinary excretion measurements, in-vivo chest counts, etc.

The ICRP biokinetic and dosimetry models do not account for dosimetric uncertainty which arises from uncertainties and variabilities in the model parameters and structure, as well as from uncertainties in the measurement data. In most of the published epidemiological studies, the internal dose estimates are usually point values provided without uncertainties7,8. For reliable risk estimation, it is important to account for uncertainties in dose estimates9.

Bayesian analysis approach which provides a distribution of dose estimates rather than a single point value10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 has been recently employed in epidemiological risk models18,19,20,21,22. Since the true dose is unknown, the base modeling assumption is that Bayesian methods yield information on the true dose, which is part of the posterior distribution9. It is assumed that the true dose can be adequately described by an arithmetic mean of a posterior dose distribution7,22,23, or that with enough exposure realizations, one or more dose vectors can be found to be or close to be the true dose vector8,20,21. This study aims to evaluate the assumptions using the “true” dose measurements from human tissue and organ samples collected postmortem. The time-dependent radionuclide activity deposited/retained in organ/tissue is directly related to the radiation dose, thus precision in organ activity prediction using biokinetic modeling can serve as a surrogate for the uncertainties in radiation dose estimations.

The United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries (USTUR) is a unique resource of human data from voluntary tissue donors (posthumously) with documented occupational intakes of actinides24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The USTUR currently retains records on exposure history and bioassay measurements, as well as post-mortem tissue radiochemical analysis results for 369 Registrants. More than 70% of these individuals were exposed to various types of plutonium (238Pu, 239Pu) material with inhalation as a primary route of intake.

In this study, uncertainties in biokinetic model predictions of organ activities as surrogates of radiation dose estimates from internally deposited 239Pu were evaluated using data from a group of 20 deceased USTUR Registrants.

Materials and methods

This study was performed as a part of the USTUR research program, which was reviewed and approved by the Central Department of Energy Institutional Review Board (USA) No. WASU-68-50181. All measurement and data analysis methods used in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All tissue donors to the USTUR, or their legal representative(s), signed a written authority for autopsy and detailed study of the collected organs and tissues, as well as for the release of radiation exposure and medical records.

Study group

The study group is comprised of two subgroups of ten deceased USTUR Registrants each from Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL)31 and from Rocky Flats Plant (RFP). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals and/or their legal representative(s) according to the USTUR human subjects assurances protocol.

Table 1 summarizes information on study cases including the worksite, smoking status, exposure duration, time after exposure to death, and estimated post-mortem activities in the liver, skeleton, and respiratory tract (RT).

LANL subgroup

Ten individuals included in the LANL subgroup were members of the ‘UPPU’ (You Pee Pu) club, a group of 26 former Manhattan Project plutonium workers who were selected by the worksite health physics personnel for medical follow-up due to their high intakes of plutonium32. The ‘UPPU’ club members worked in plutonium purification, fluorination, and reduction operations under “extraordinary crude conditions” at Los Alamos Scientific (now National) Laboratory in the 1940s and handled large quantities of plutonium, from milligrams to kilograms32,33. Over the several decades post-exposure, the worksite personnel periodically conducted medical examinations of the ‘UPPU’ members, as well as bioassay measurements to estimate intakes and systemic deposition of plutonium. This follow-up was reported in multiple publications32,34,35,36,37.

Thirteen ‘UPPU’ members voluntarily registered to be tissue donors at the USTUR. Ten out of these 13 (seven whole-body and four partial-body tissue donors) were included in this study, because only for these ten cases, the tissue radiochemical analysis results were available for all three key target organs (liver, skeleton, and respiratory tract).

All individuals in this subgroup had significant potential for both chronic and acute inhalation intakes. Based on the worksite exposure records, the most common material encountered by these workers during their operational activities was assumed to be 239Pu nitrate with small particle sizes, typically < 1 μm AMAD (activity median aerodynamic diameter).

Case descriptions and selected data were previously published elsewhere31,38.

RFP subgroup

Ten individuals included in this subgroup (six whole-body and four partial-body tissue donors) worked at RFP during the 1950s-1960s. Based on their job descriptions, as well as plutonium processing operations routinely conducted at the facility, these workers mostly were exposed to relatively insoluble plutonium materials via both acute and chronic inhalation; however, contaminated wounds were also common.

All individuals in the RFP subgroup, except Case 0706, were involved in the same acute inhalation accident due to a glove-box fire which resulted in significant release of the airborne ‘high-fired’, refractory 239PuO2. The particle size of the released aerosols, generated at an estimated temperature of 1800 °C, was measured as a 0.32-µm mass median diameter (MMD), equivalent to 1 μm AMAD, with a geometric standard deviation (GSD) of 1.83. The detailed description of the accident was reported elsewhere39,40. The magnitudes of inhalation exposure encountered by these workers during the accident differ significantly, given their work locations and proximity to the fire. Based on worksite exposure records, the fire accident was a single or major plutonium internal deposition event for five individuals, while the remaining four were also involved in other significant internal contamination incidents.

Case 0706 had two major incidents: plutonium contaminated wound and acute inhalation confirmed by the positive chest measurement.

Data

Data used for biokinetic modeling includes urine bioassay measurements and post-mortem activities in the liver + skeleton and respiratory tract.

Bioassay

At both worksites, urine measurement techniques and, consequently, analysis precision/accuracy varied over time41,42. In historical records, specific information on measurement uncertainties, as well as sample-specific limits of detection (LOD) and/or minimum detectable activities (MDA) are not commonly available. To check the data against the historical limits of detection, median MDA values for the corresponding time periods provided in the technical basis documents for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Radiation Dose Reconstruction Program41,42 were used. The reported urine bioassay measurement results equal or greater than the MDA/2 were assumed to be positive and treated as real data in calculations. The less than MDA/2 measurements were replaced by MDA/2 and marked as ‘ < LOD’. Urinary excretion rates for the LANL subgroup cases were previously published31. Urine data for the RFP subgroup are provided as Supplementary Tables S1–S10.

No measurement uncertainties were reported for any study cases in both subgroups. To account for uncertainties in urine data, a standard assumption of lognormal error distribution43 was used with GSD values chosen to represent the level of confidence that can be placed in the corresponding measurement techniques. The GSD values for LANL cases were 3.0 for data before 1949, 2.0 between 1949 and 1957, and 1.6 after 195731. For RFP cases, GSD of 2.0 was used.

Unlike the LANL subgroup where a few available in vivo chest measurements (if any) are typically below the detection limits, historical data for the RFP cases includes extensive sets of positive chest measurement results. However, analysis of all cases was performed using urine data only, which is the most common approach for dose assessment in radiation epidemiology7,44.

Post-mortem tissue activities

The post-mortem measurement results of plutonium activities in the liver, skeleton and respiratory tract with the total propagated uncertainties are provided in Table 1. Plutonium was radiochemically separated from acid-digested tissue samples and measured using alpha-spectrometry45,46.

In calculations, plutonium activities in the liver and skeleton were combined to minimize the effect of a wide inter-individual variation in the partitioning of activity between these organs38,47,48. The uncertainties in the liver + skeleton and respiratory tract activities were assumed to be normally distributed with an arbitrary standard deviation (SD) of 10%.

Exposure scenario

In a conventional dosimetric approach for radiation epidemiology, it is common to assume chronic intakes over the entire period of employment (e.g.7). This is typically done to standardize the dose assessment procedure across the large cohorts of exposed individuals and because detailed information on specific exposure incidents may not be available for all individuals in the cohort. Therefore, to quantify uncertainties expected in radiation dose assessment for epidemiology, an assumption of chronic inhalation of plutonium with a particle size of 1 µm AMAD during entire employment (Table 1) was adopted in this study.

Analysis

The Bayesian statistical approach was used in this study to calculate uncertainties in biokinetic model parameters and predictions expressed in the form of posterior probability distributions conditional on measurement data. The Bayes’ theorem defines the joint posterior probability distribution of intake and model parameters, given the measurement data as:

where P(I) and P(p) are the prior probability density functions of intake and the vector of model parameters p, respectively, and \(L\left( {{\varvec{M}}{|}I,{\varvec{p}}} \right)\) is the joint likelihood function representing the conditional probability density function of observing the vector of measurements M given intake I and the model parameters p10,12,14. Hence, this approach allows incorporating all available prior knowledge concerning the exposure scenario into biokinetic calculations. In other words, the prior probability distribution which defines the state of knowledge on the quantities of interest (material characteristics, model parameters, etc.) can be updated when relevant information (e.g. bioassay measurement data) is obtained. Selection of prior distributions for parameters is of great importance and must be based on objective information available for the problem.

The likelihood function described in IDEAS Guidelines43 was used for the interpretation of measurement values:

where Mi is the measurement value, I is the intake amount, and fi(p) is the retention or excretion function per unit intake calculated using the model parameters p; SFi is the total scattering factor given as follows:

This equation includes two components:

-

1.

Type A component, \(SF_{{A_{i} }}\) which represents uncertainty arising solely from measurement statistics and can be calculated as \(SF_{{A_{i} }} = exp\left( {\frac{{\sigma_{i} }}{{M_{i} }}} \right)\), where σi is the SD, estimated using the normal approximation.

-

2.

Type B component, \(SF_{{B_{i} }}\) which accounts for uncertainty dominated by biological variability.

The combined likelihood function, \(L\left( {M_{i} {|}I,{\varvec{p}}} \right)\) is the product of the likelihood functions for n independent measurements:

The chi-square test statistics calculated as:

was used to examine the goodness-of-fit for the realization of different vectors of model parameters.

Implementation of biokinetic models

The retention or excretion functions, fi(p), after an inhalation intake were calculated by solving the system of models (Fig. 1) which consists of the ICRP 1302 human respiratory tract model (HRTM), the ICRP 10049 human alimentary tract model (HATM), and the ICRP Publication 1415 systemic model for plutonium.

The biokinetic models were implemented in the in-house code USTUR-iRAD, a new, flexible, adaptable computer code for radiation dosimetry following intakes of actinides. Python 3.9 was chosen as the programming language50,51. The USTUR-iRaD is designed in an object‐oriented manner and can be run in the command line environment as a single realization or as a batch, simplifying studies on uncertainties.

Calculations are based on analytical solutions of the systems of linear differential equations representing the models using a slightly modified version of the Birchall and James52 rate matrix algorithm. Briefly, if [R] is the matrix of transfer rates in the compartmental model, the amount in the model compartments at time t is given by

where matrix [A] was obtained by replacing the diagonal elements of each row of [R] with the negative of the sum of the transfer rates in that row and the decay constant and then transposing the matrix, and x(0) is the column vector of initial quantities in the model compartments. The initial quantity x(0) is obtained from the HRTM deposition model with deposition fractions for a reference worker for assumed particle size of 1 µm taken from Annex A of ICRP Publication 1302.

The instantaneous activity in a compartment i at time t is the ith element of the column matrix x(t). For excretion quantities such as urine, the 24-h excretion on day t is given by the difference between the instantaneous activity in the “urine” compartment at t and that at t − 1, corrected for radioactive decay.

The biokinetic models were validated by comparison with predictions generated using the IMBA Professional Plus internal dosimetry software53, special research version 4.1.66. The USTUR version of the IMBA enables modification of HRTM parameters, including those related to deposition, particle transport and absorption, as well as the construction and solution of compartmental systemic models. As the standard IMBA module does not incorporate the most recent biokinetic models recommended by the ICRP in its OIR series, the updated HRTM from ICRP Publication 1302 and plutonium systemic model from ICRP Publication 1415 were implemented in IMBA using these advanced customization features.

Prior distributions

There is no recommended set of priors for biokinetic model parameters, and each parameter has a different impact on the results of analyses7,14,15,54,55.

Sensitivity analysis was performed for following HRTM parameters: fraction dissolved rapidly, fr, slow dissolution rate, ss; particle transport rates alveoli to bronchioles (ALV to bb), alveoli to interstitium (ALV to INT), interstitium to LNTH (INT to LNTH), and kPT—factor to multiply the remaining particle transport rates.

Only fr and ss were used in the final analysis. A uniform prior distribution between 0 and 0.2 was used for fr and a lognormal prior with a median of 0.00005 d–1 and GSD of 6 truncated at 0.002 d–1 was used for ss. The bounds for fr were selected based on the assumption that its value was likely to lie below the default value for 239Pu nitrate. The selected median of prior distribution for ss is between the default values for 239Pu dioxide and Pu-nitrate and the truncation limit was set to eliminate the values higher than the upper limit of this range. All other parameters were fixed at their default values2,5.

Calculations

To calculate posterior probability distributions, the USTUR-iRaD was run in a batch mode using a Latin hypercube sampling56 to generate 5000 sets of parameters, same for all 20 cases. Each set of parameters determines one realization. Each realization consists of two steps: (i) fitting measurement data and estimating intake with the corresponding ‘goodness-of-fit’ statistics, and (ii) using the intake to predict the organ activity at the time of death, both with a sampled set of model parameters. The maximum likelihood method was used for fitting the data. The fit was performed twice using: (i) the urine bioassay data and (ii) the post-mortem tissue analysis data (plutonium activities in the respiratory tract and the liver + skeleton). In total, for 20 cases, 200,000 realizations (20 × 2 × 5000) were ran.

The likelihood of each realization (i.e. each set of parameters) was the value of the likelihood function calculated for the maximum likelihood fit of either urine bioassay data or post-mortem tissue measurements. The likelihood value was recorded for each realization. The posterior probability distribution was constructed by weighing the prior values by the likelihood.

Additionally for comparison, the intake scenarios were simulated using the default absorption parameters for 239Pu nitrate and 239PuO2.

Results

Based on the sensitivity analysis results, the derived posterior distributions for the particle transport model parameters, ALV to bb, INT to LNTH, ALV to INT and kPT, did not significantly differ from the corresponding priors indicating that the data were not informative for these parameters.

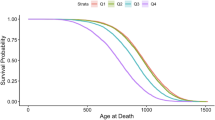

Results of final analysis are presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Model parameter posterior distributions

Figures 2 and 3 and Tables 2 and 3 show the posterior probability distributions and the descriptive statistics for model parameters, fraction dissolved rapidly, fr, and slow dissolution rate, ss. The plots show the priors, as well as the posterior probability distributions derived from (i) post-mortem tissue radiochemical analysis results only (autopsy-posterior) and (ii) the urine bioassay measurement data only (urine-posterior). The descriptive statistics including mean, median, geometric mean (GM), SD, GSD are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Organ activity prediction

Figures 4, 5, 6 and Tables 4, 5, 6 summarize a posteriori estimates of post-mortem organ activities calculated from the posterior distributions of selected absorption parameters based on urine bioassay data with all other model parameters fixed at default values. Figures also show predictions of organ activities using default PuO2 and Pu-nitrate material parameters, as well as the ‘true’ measured values. Descriptive statistics presented in Tables 4, 5, 6 include mean, SD, median, GM, GSD, as well as 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles (Q2.5 and Q97.5, respectively).

Discussion

Bayesian approach, which provides a distribution of radiation dose estimates, can be essential to evaluate uncertainties in epidemiological risk modeling. In this study, Bayesian analysis was used to estimate uncertainties in biokinetic model predictions of long-term retention of plutonium in key target organs such as the liver, skeleton, and respiratory tract in the form of posterior probability distributions. The uncertainties derived in this study can be used as the surrogates of uncertainties in organ dose estimates for radiation epidemiology. While the true dose is unknown, it is generally assumed to be a part of the Bayesian posterior distribution9. Hence, this study provided a unique opportunity to validate this assumption.

The posterior distributions of selected absorption parameters, fr and ss, were used to determine how informative the urine and post-mortem tissue analyses data were for these parameters and, subsequently, for model predictions.

Results presented in Fig. 2 showed that, for all cases in both subgroups, the posterior distributions of the rapidly dissolved fraction, fr, constructed using likelihood values from the fit of urine data (urine-posterior) did not significantly differ from the prior. This suggests that the urine bioassay data did not provide information on this parameter. For some cases the probability of the higher fr values seemed to slightly increase for urine fits. This might be influenced by the prior distribution of the parameter ss. Both these parameters describe the same effect; the lower their value the lower the solubility of the inhaled material, therefore they are correlated. Dissolving more material into the bloodstream, and subsequently to systemic tissues, may be achieved either by increasing the fraction which dissolves rapidly (rapid dissolution rate, sr, remaining on the default value of 0.4 d–15 for all cases) or by increasing the slow dissolution rate.

The posteriors of dissolution parameters constructed using likelihood values from the fit of post-mortem tissue analyses (autopsy-posterior) are less consistent with priors (Figs. 2 and 3). In some cases, the difference is highly significant. More pronounced examples of these differences are the posterior distributions of fr for Cases 0028, 0202, 0503, and 0821 where autopsy-posteriors are very well-defined as opposed to urine-posteriors which mostly follow the prior distributions (Fig. 2). Hence, direct measurements of the activity retained in the organs seem to be more informative in terms of material solubility.

An examination of the posteriors of ss for LANL subgroup, as shown in Fig. 3, indicates that the posterior distributions derived from urine bioassay data tend to have higher probability densities in the lower ss values. In contrast, the posterior distributions based on post-mortem tissue measurements exhibit the higher probabilities at greater ss values, suggesting exposure to more soluble material for LANL cases except Cases 0060 and 0193, whose distributions indicate inhalation of more insoluble compounds. Therefore, the overall pattern of autopsy-posteriors for this subgroup is more consistent with available information on predominantly soluble plutonium material more likely encountered at the worksite during the corresponding exposure period.

Nine out of ten RFP cases were involved in the same incident that resulted in inhalation of ‘high fired’ PuO2 particles and, therefore, could be assumed to be exposed to the same, likely insoluble material. Figure 2 shows that data for most of these nine cases are in fact more consistent with the inhalation of insoluble plutonium compounds. Moreover, four of these individuals, for whom the fire incident was the major internal contamination event, appear to be exposed to extremely insoluble material (Cases 0028, 0202, 0503, 0821). The posterior distributions for these cases are significantly different from all other study cases. The medians of fr posteriors are 0.004, 0.011, 0.015, and 0.010 for Cases 0028, 0202, 0503, 0821, respectively. The entire posterior histograms lie below 0.04. In simulation practice, this may cause undersampling of other potentially relevant parameter values since 80% of the realizations have practically zero likelihood (0.04–0.20) and, therefore, do not contribute to the posterior distribution. Moreover, the posterior distributions of ss for these cases have the lowest medians among all cases confirming highly insoluble material: 4.4 × 10–6, 4.1 × 10–6, 4.2 × 10–6, 3.8 × 10–6, respectively. These values are consistent with previously published evaluations of Cases 0202 and 040739,54,57.

Data from Cases 0720 and 0744 suggest higher solubility not consistent with the ‘high fired’ plutonium inhalation. These two individuals had additional significant intakes (inhalations and/or wounds) other than the fire incident which can explain this difference. Exposure material was less insoluble also for Case 0706 who was not involved in the fire incident.

The above-mentioned examples show the danger of assigning material solubility parameters according to a worksite. Individual analysis of all data about a worker seems to be essential for proper analysis. Using the chest count results, if available, can be critical to correctly assign the solubility parameters of the inhaled plutonium material.

For all cases, a posteriori (weighted by fit likelihood) predictions of organ activities at time of death were calculated from urine bioassay and compared to the measured values, as well as predictions using default Pu-nitrate and 239PuO2 parameters.

Results demonstrated that the distributions of organ activity predictions did not cover the measured values in most cases (Figs. 4, 5, 6).

The measured liver activity for 15 cases lay outside of the boundaries of 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles. The distributions of the liver activity were relatively narrow, the GM ratio of 97.5% and 2.5% quantiles was 1.53 for all cases (Table 4). The mean absolute bias between measured activity and median of the distribution was 59%.

Only for two cases the measured skeleton activity lay between 2.5% and 97.5% quantile boundaries. The GM of the boundary ratios was 1.45 (Table 5), indicating that the distributions were even narrower in general. The mean absolute bias of the median to the measured skeleton activity was 56%.

For the respiratory tract, the urine data did not provide any useful information. The distributions were very wide; the GM ratio of quantile boundaries was 228 (Table 6). However, even with these extremely broad distributions, the measured value lay outside the boundaries for 10 out of 20 cases. The mean absolute bias of the distribution medians was 989%.

In radiation protection, underestimations should generally be avoided to stay conservative. The measured liver and skeleton activities were higher than the 97.5% quantile for nine and eight cases, respectively, indicating that the calculations underestimated the true activity. For the respiratory tract, the true values were greater than the predicted 97.5% quantile for only four out of 20 cases, however, it is important to emphasize again the very large values of the corresponding 97.5% quantiles for the respiratory tract activity (Table 6).

Conclusions

In this study, Bayesian analysis was used to estimate uncertainties in biokinetic model predictions of long-term retention of plutonium in key target organs such as the liver, skeleton, and respiratory tract in the form of posterior probability distributions. The uncertainties derived in this study can be used as the surrogates of uncertainties in organ dose estimates for radiation epidemiology.

Analysis showed that the choice of an appropriate prior for each model parameter is critical for accurate interpretation of the data and for the efficient use of computational resources.

Urine bioassay did not provide conclusive information on material solubility parameters for the selected cases. Site-specific material solubility parameters might not be reliable in some cases. Post-mortem tissue analysis of the respiratory tract or in vivo chest measurements during life are essential to correctly assign the solubility parameters of the inhaled material.

Application of current biokinetic models to urine bioassay data provided narrow a posteriori distributions for systemic organ activity predictions with median values within 60% of measured organ activities. However, median predictions of the respiratory tract activity based on urine data were highly inaccurate. Calculated distributions of organ activity predictions did not cover the measured values in most cases (75% for the liver, 90% for the skeleton, and 50% for the respiratory tract) suggesting that the Bayesian modeling approach of uncertainty analysis in dose assessment using the current biokinetic models may not be adequate in providing “true dose” information for epidemiological risk models.

In addition, the model predictions were not conservative for some cases; the upper 97.5% boundaries of distributions were lower than the measured values in 45% of the cases for the liver, 40% for the skeleton, and 20% for the respiratory tract. This might pose a problem for radiation protection if not accounted for.

Data availability

The parts of the dataset used and analyzed during the current study, which were not previously published elsewhere, are included in this published article and its supplementary file. The remaining part of the dataset was previously published and is available for download at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259057.s001.

Abbreviations

- ALV:

-

Alveoli

- AMAD:

-

Activity median aerodynamic diameter

- bb:

-

Bronchioles

- BB:

-

Bronchi

- GM:

-

Geometric mean

- GSD:

-

Geometric standard deviation

- HATM:

-

Human Alimentary Tract Model

- HRTM:

-

Human Respiratory Tract Model

- ICRP:

-

International Commission on Radiological Protection

- IMBA:

-

Integrated Modules for Bioassay Analysis

- INT:

-

Interstitium

- LANL:

-

Los Alamos National Laboratory

- LNTH:

-

Thoracic lymph nodes

- LOD:

-

Limit of detection

- MDA:

-

Minimum detectable activity

- MMD:

-

Mass median diameter

- NCRP:

-

National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements

- NIOSH:

-

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- RFP:

-

Rocky Flats Plant

- RT:

-

Respiratory tract

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- USTUR:

-

United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries

References

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP 37 (2-4), 1–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icrp.2007.10.003 (2007).

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection. Occupational intakes of radionuclides: Part 1. ICRP Publication 130. Ann. ICRP 44 (2), 5–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146645315577539 (2015).

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection. Occupational intakes of radionuclides: Part 2. ICRP Publication 134. Ann. ICRP 45 (3/4), 7–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146645316670045 (2016).

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection. Occupational intakes of radionuclides: Part 3. ICRP Publication 137. Ann. ICRP 46 (3/4), 1–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146645317734963 (2017).

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection. Occupational intakes of radionuclides: Part 4. ICRP Publication 141. Ann. ICRP 48 (2–3), 9–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146645319834139 (2019).

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection. Occupational intakes of radionuclides: Part 5. ICRP Publication 151. Ann. ICRP 51 (1–2), 1–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/01466453211028755 (2022).

Puncher, M. & Riddell, A. E. A Bayesian analysis of plutonium exposures in Sellafield workers. J. Radiol. Prot. 36(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1088/0952-4746/36/1/1 (2016).

Simon, S. L., Hoffman, F. O. & Hofer, E. The two-dimensional Monte Carlo: a new methodologic paradigm for dose reconstruction for epidemiological studies. Radiat. Res. 183(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1667/rr13729.1 (2015).

[NCRP] National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Commentary No. 34 – Recommendations on statistical approaches to account for dose uncertainties in radiation epidemiologic risk models. (National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, 2024).

Miller, G., Inkret, W. C. & Martz, H. F. Internal dosimetry intake estimation using Bayesian methods. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 82(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a032606 (1999).

Miller, G., Martz, H. F., Little, T. & Guilmette, R. Bayesian internal dosimetry calculations using Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 98(2), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006709 (2002).

Miller, G., Little, T. & Guilmette, R. The application of Bayesian techniques in the interpretation of bioassay data. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 105(1–4), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006252 (2003).

[NCRP] National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Report No. 164 – Uncertainties in internal radiation dose assessment. (National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, 2009).

Puncher, M. & Birchall, A. A Monte Carlo method for calculating Bayesian uncertainties in internal dosimetry. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 132(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncn248 (2008).

Puncher, M., Birchall, A. & Bull, R. K. Uncertainties on lung doses from inhaled plutonium. Radiat. Res. 176(4), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1667/rr2410.1 (2011).

Puncher, M., Birchall, A. & Bull, R. K. A method for calculating Bayesian uncertainties on internal doses resulting from complex occupational exposures. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 151(2), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncr475 (2012).

Riddell, A. E., Birchall, A., Puncher, M., Efimov, A. & Vostrotin, V. Report on the development and validation of plutonium dose assessment systems for epidemiological research. SOLO Sub-Project 3. Work Package 3.3 – Deliverable 3.3.1 (2015)

Bellamy, M. B. et al. Recommendations on statistical approaches to account for dose uncertainties in radiation epidemiologic risk models. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 100(10), 1393–1404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553002.2024.2381482 (2024).

Hofer, E. Discrete Bayesian dose-response analysis under dose uncertainty. Health Phy. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000001965 (2025).

Kwon, D., Hoffman, F. O., Moroz, B. E. & Simon, S. L. Bayesian dose-response analysis for epidemiological studies with complex uncertainty in dose estimation. Stat. Med. 35(3), 399–423 (2016).

Kwon, D., Simon, S. L., Hoffman, F. O. & Pfeiffer, R. M. Frequentist model averaging for analysis of dose-response in epidemiologic studies with complex exposure uncertainty. PLoS ONE 18(12), e0290498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290498 (2023).

Stram, D. O. et al. Lung cancer in the Mayak Workers Cohort: risk estimation and uncertainty analysis. Radiat. Res. 195(4), 334–346. https://doi.org/10.1667/rade-20-00094.1 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Correction of confidence intervals in excess relative risk models using Monte Carlo dosimetry systems with shared errors. PLoS ONE 12(4), e0174641. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174641 (2017).

Breitenstein, B.D. Jr. The U.S. transuranium registry. In Actinides in Man and Animals (ed. Wrenn, M. E.) 269–272 (RD Press, 1981).

Bruner, H. D. A plutonium registry. In Diagnosis and Treatment of Deposited Radionuclides (eds. Kornberg, H. A. & Norwood, W. D.) 661–665 (Excerpta Medica Foundation, 1968).

Filipy, R. E. & Russell, J. J. The United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries as resources for actinide dosimetry and bioeffects. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 105(1–4), 185–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006220 (2003).

Kathren, R. L. The United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries—1968–1993. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 60(4), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a082740 (1995).

Kathren, R. L. & Tolmachev, S. Y. The United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries (USTUR): A five-decade follow-up of plutonium and uranium workers. Health Phys. 117(2), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/hp.0000000000000963 (2019).

Miller, G. et al. Worldwide bioassay data resources for plutonium/americium internal dosimetry studies. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 125(1–4), 531–537. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncm164 (2007).

Norcross, J. A. & Newton, C. E. US Transuranium Registry: a progress report. Health Phys. 22(6), 887–890 (1972).

Šefl, M., Zhou, J. Y., Avtandilashvili, M., McComish, S. L. & Tolmachev, S. Y. Plutonium in Manhattan Project workers: Using autopsy data to evaluate organ content and dose estimates based on urine bioassay with implications for radiation epidemiology. PLoS ONE 16(10), e0259057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259057 (2021).

Hempelmann, L. H., Langham, W. H., Richmond, C. R. & Voelz, G. L. Manhattan Project plutonium workers: a twenty-seven year follow-up study of selected cases. Health Phys. 25(5), 461–479. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-197311000-00001 (1973).

Inkret, W. C. & Miller, G. On the front lines: plutonium workers past and present share their experiences. Los Alamos Science 23, 125–173 (1995, accessed 6 Mar 2025). https://permalink.lanl.gov/object/tr?what=info:lanl-repo/lareport/LA-UR-95-4005-05).

Voelz, G. L., Grier, R. S. & Hempelmann, L. H. A 37-year medical follow-up of Manhattan Project Pu workers. Health Phys. 48(3), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-198503000-00001 (1985).

Voelz, G. L., Hempelmann, L. H., Lawrence, J. N. & Moss, W. D. A 32-year medical follow-up of Manhattan Project plutonium workers. Health Phys. 37(4), 445–485. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-197910000-00001 (1979).

Voelz, G. L. & Lawrence, J. N. A 42-y medical follow-up of Manhattan Project plutonium workers. Health Phys. 61(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-199108000-00001 (1991).

Voelz, G. L., Lawrence, J. N. & Johnson, E. R. Fifty years of plutonium exposure to the Manhattan Project plutonium workers: an update. Health Phys. 73(4), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-199710000-00004 (1997).

Šefl, M., Avtandilashvili, M. & Tolmachev, S. Y. Inhalation of soluble plutonium: 53-year follow-up of Manhattan project worker. Health Phys. 120(6), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000001396 (2021).

Avtandilashvili, M., Brey, R. & James, A. C. Maximum likelihood analysis of bioassay data from long-term follow-up of two refractory PuO2 inhalation cases. Health Phys. 103(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0b013e31824ac627 (2012).

Mann, J. R. & Kirchner, R. A. Evaluation of lung burden following acute inhalation exposure to highly insoluble PuO2. Health Phys. 13, 877–882. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-196708000-00007 (1967).

[ORAUT] Oak Ridge Associate Universities Team. Los Alamos National Laboratory – Occupational internal dose. Technical Basis Document ORAUT-TKBS-0010-5 Revision 02 (2013, accessed 27 Jan 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ocas/pdfs/tbd/lanl5-r2.pdf.

[ORAUT] Oak Ridge Associate Universities Team. Rocky Flats Plant—occupational internal dose. Technical Basis Document ORAUT-TKBS-0011-5 Revision 04 (2020, accessed 27 Jan 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ocas/pdfs/tbd/rocky5-r4-508.pdf.

Castellani, C. M. et al. IDEAS guidelines (Version 2) for the estimation of committed doses from incorporation monitoring data. EURADOS Report 2013–01 (2013, accessed 5 June 2025). https://eurados.sckcen.be/sites/eurados/files/uploads/Publications/24_EURADOS-Report-2013-01_online-version.pdf.

Boice, J. D. Jr. et al. Mortality among workers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1943–2017. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 98(4), 722–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553002.2021.1917784 (2022).

McInroy, J. F., Kathren, R. L. & Swint, M. J. Distribution of plutonium and americium in whole bodies donated to the United States Transuranium Registry. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 26(1–4), 151–158 (1989).

Tolmachev, S. Y., James, A. C., Ketterer, M. E., Hare, D. & Doble, P. The US Transuranium and Uranium Registries: forty years’ experience and new directions in the analysis of actinides in human tissues. Proc. Radiochem.: A Suppl. Radiochim. Acta 1(1), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1524/rcpr.2011.0032 (2011).

Klein, W. & Breustedt, B. Analysis of the effects of inter-individual variation in the distribution of plutonium in skeleton and liver. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 158(3), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/nct233 (2014).

Leggett, R. W. et al. Mayak worker study: an improved biokinetic model for reconstructing doses from internally deposited plutonium. Radiat. Res. 164(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1667/rr3371 (2005).

[ICRP] International Commission on Radiological Protection. Human alimentary tract model for radiological protection. ICRP Publication 100. Ann. ICRP 36 (1–2), 5–336 (2006).

Pilgrim, M., & Willison, S. Dive into Python 3. Vol. 2 (Springer, 2009).

Van Rossum, G. & Drake, F.L. Python 3 Reference Manual (CreateSpace, 2009).

Birchall, A. & James, A. C. A microcomputer algorithm for solving first-order compartmental models involving recycling. Health Phys. 56(6), 857–868. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-198906000-00003 (1989).

Birchall, A. et al. IMBA Professional Plus: a flexible approach to internal dosimetry. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry. 125(1–4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncl171 (2007).

Avtandilashvili, M., Brey, R. & Birchall, A. Application of Bayesian inference to the bioassay data from long-term follow-up of two refractory PuO2 inhalation cases. Health Phys. 104(4), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0b013e31827fd5cf (2013).

Poudel, D. et al. Long-term retention of plutonium in the respiratory tracts of two acutely-exposed workers: estimation of bound fraction. Health Phys. 120(3), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1097/hp.0000000000001311 (2021).

McKay, M. D., Beckman, R. J. & Conover, W. J. A comparison of three methods for selecting values of input variables in the analysis of output from a computer code. Technometrics 42(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00401706.2000.10485979 (2000).

Poudel, D. et al. Modeling of long-term retention of high-fired plutonium in the human respiratory tract—importance of scar-tissue compartments. J. Radiol. Protect. 41(4), 940–961. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6498/abca49 (2021).

Funding

The USTUR is funded by U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Domestic and International Health Studies (EHSS-13), under grant award DE-HS0000073 to Washington State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Š. and M.A. prepared and analyzed all data. M.A., M.Š., J.Y.Z., and S.Y.T. prepared the manuscript. M.Š. designed the in-house biokinetic code USTUR-iRaD. J.Y.Z. and S.Y.T. designed and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review

This study was performed as a part of the USTUR research program, which was reviewed and approved by the Central Department of Energy Institutional Review Board (USA) No. WASU-68-50181.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Avtandilashvili, M., Šefl, M., Zhou, J.Y. et al. Validation of Bayesian modeling approach of uncertainty in organ doses using post-mortem measurements. Sci Rep 15, 20476 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04799-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04799-3