Abstract

Accurate measurement and verification (M&V) of energy efficiency measures (EEM) in commercial buildings is a key requirement to improve energy performance and meet sustainability goals. Research suggests a new method to M&V EEM using generalized additive models (GAM) to provide a way to measure how EEMs perform across different commercial buildings (i.e., offices, mixed-use developments, and healthcare). Comparisons suggest GAM is a preferred method of predicting energy savings from previous years and provides good estimates on a new dataset (comparable to previous years). The CV(RMSE) value is acceptably low. Lighting upgrades and HVAC improvements are areas of best practice for energy savings, and all sectors studied achieved significant energy savings with reasonable return times on investment compared to all other studies conducted to date (examples include offices and healthcare). We also focus on and show climate-related factors affecting energy consumption and had some success differentiating results based primarily on temperature/RH relative humidity-triggered variables and indicated the primary “thresholds” that appeared to alter energy demand behavior. Particular high humidity and temperatures carry serious energy penalties, and future climate change calls for climate-responsive energy policies. Furthermore, Monte Carlo simulations were used to measure uncertainty and backlog of data readings, not all prompted by climate factors alone, to confirm our results were sound.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Buildings form a major part of global energy consumption and associated emissions and thus highlight the need for accurate measurement and verification (M&V) of energy efficiency measures (EEMs) for building operation optimization and achieving sustainability plans1,2. Commercial buildings, for instance, have very heterogeneous energy demand due to heterogeneous occupancy patterns, schedules of operation, and varying climate conditions3. These concerns have fostered increased attention to advanced, data-driven modeling methodologies for enhancing accuracy as well as credibility of quantification of energy saving with actionable inputs for building managers and policymakers4,5,6. Data-driven methods with a blend of real-time data and advanced algorithms hold great potential for building operation optimization and achieving visions of sustainability.

Traditional M&V methods are likely to use base models calibrated based on pre-retrofit only6,7. It neglects the potential of the information provided by post-retrofit end-use profiles due to environmental and building operation variability8,9. Consequently, those models may degrade their forecasting performance when only a few pre-retrofit data are available10,11. The widely applied time-of-week-and-temperature (TOWT) model12, for instance, is generally not flexible enough to handle varied post-EEM energy use profiles.

More recent studies have advanced M&V methods by integrating intensive consumption records with climate and operating records so that models could be able to distinguish dynamic and nonlinear relationships between energy consumption and climate drivers13,14. More advanced methods based on machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques are being widely implemented for further validation of energy savings purposes within industrial and commercial applications15,16,17. These methods can recognize typical energy use patterns, temperature changes, and people’s schedules, which helps to better understand how things work behind the scenes. Depending on those endeavors, the present research proposes a better M&V strategy that (a) fully leverages the full series of energy consumption records—pre- and post-EEM implementation—and (b) provides extra building performance indicators18. More specifically, the new method employs generalized additive models (GAMs) for unmasking the relationships between climate variables, indoor operations adjustments, and occupant-driven loads19,20. These kinds of methods have a tendency to unmask main load profiles, change-point temperatures, and behavioral effects to improve estimates of the baseline. Based on this, the present research proposes a new M&V scheme that utilizes Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) to fully leverage the pre- and post-EEM time series. GAMs offer a flexible and interpretable modeling platform that is able to identify nonlinear dependencies and various EEM impacts simultaneously.

By combining various sources of data and advanced statistical methods, the method aims to overcome the limitations of standard M&V practice by offering higher levels of predictability and more comprehensive diagnostics, particularly where there are brief or partial sets of baseline data21,22. The remainder of the paper describes the methodological framework, presents case examples showing application of the method, and discusses the implications for wider practical application of advanced M&V methods23,24,25,26. The following sections explain the methods used, show examples of case studies, and talk about how using advanced data-driven M&V methods can help manage energy in sustainable buildings.

Literature review

The global setting for building energy consumption

Global usage of energy is confronting a highly demanding intersection of ecological sustainability, technology transition, and building design27. Buildings are a major intersection point within the rich ecological network, responsible for a whopping 38.2% of the global energy-linked carbon footprint, as calculated from the latest holistic evaluation of the International Energy Agency28. A statistic like that illustrates perfectly the absolute importance of designing new forms of transdisciplinary solutions for energy efficiency that go beyond traditional methodological limitations.

Building energy management has gone along a gigantic trajectory of scientific and technological advancement29. The discipline has evolved from rudimentary methods of reducing energy consumption to modern methods that involve highly sophisticated interactions with the environment. Buildings are nowadays recognized by research as dynamic ecosystems rather than stationary objects that are highly interlinked with their environment, occupant activity, and technological networks30.

Methodological shift towards energy efficiency measurement

Historically, building energy performance practices for measuring and validating had serious deficiencies31. Standard methods relied heavily on linear regression models with assumptions of stationary, linear associations between energy consumption and drivers of the environment32. Elementary baseline comparison methods were applied within those models, which failed to consider the dynamics of building energy22,33.

As the scientists encountered increasingly complicated urban and building context, the limitations of those traditional methods became clearer34. Office buildings with their complicated working schedules, mixed occupancy levels, and highly automated building services defied reductionist simulation methods35,36. More research is now concentrating on the urgent need for new, adaptable, and combined models that can show the complex relationship between buildings and their energy use37,38,39.

Scholars such as Delia D’Agostino et al.40 have contended that energy efficiency modeling should move beyond deterministic methods, adopting probabilistic models that accept uncertainty and variability. This is a shift that represents much more than a methodological move: instead, it is a fundamental rethinking of how, as a field, we know and engage with building energy systems.

Advanced modeling techniques: a technological renaissance

Generalized additive models (GAMs) are an important development in studying how buildings use energy41. Unlike traditional linear models, they offer great flexibility in examining complex relationships between different factors42. GAMs are an advanced statistical tool that can analyze the complicated interactions between environmental conditions, operational factors, and energy usage patterns all at once43.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies have created new opportunities for studying energy efficiency44. New algorithms can handle large amounts of data and find patterns that other methods can’t see. Models based on neural networks and ensemble machine learning help researchers create highly detailed and accurate prediction models45,46,47.

Dr. Ali has ascertained that advanced machine-learning models are able to achieve accuracy levels over 92% in predicting energy consumption for diverse building types. Her research is within the general line of technology-driven, integrated energy management solutions48.

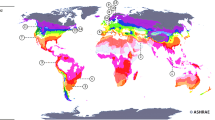

Climate zone dynamics and environmental interactions

Building energy performance geographic context is a key area neglected by past research paradigms49. Climate zones indicate that there is significant variability in the nature of energy consumption, which necessitates the use of local, context-based analysis tools. Temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and atmospheric conditions interrelate intricately and impose a tremendous effect on building energy dynamics50.

Current research has provided intriguing results on these environmental interactions. For example, research conducted over Chinese climatic zones has indicated that humidity can increase energy usage by as much as 35% at peak temperatures51. Such findings highlight the necessity of developing adaptive modeling approaches that possess the ability to respond dynamically to changes within the environment.

Climate sensitivity has emerged as a unifying concept for building energy research over the past decade or so. Rather than being defined separately, buildings are viewed nowadays as adaptive organisms that continuously mediate multidimensional transactions with the environment. This perspective requires holistic modeling strategies that can cope with more than a single variable at a time.

Energy efficiency measures: a general overview

Repeated empirical research has identified several key strategies for achieving substantial energy saving across a range of building types:

Lighting is a major opportunity area for energy efficiency. New LED technologies, when integrated with intelligent control systems, are able to reduce lighting energy consumption by as much as 75% compared with traditional lighting technologies52,53. This research pioneers the dynamic adjustment of light levels based on occupancy and ambient light levels54.

Another important intervention strategy that would assist in achieving energy efficiency is HVAC optimization. Through advanced control algorithms and incorporating predictive maintenance approaches, buildings can achieve significant energy efficiency gains55. As machine learning algorithms can forecast upcoming system inefficiencies before they happen, proactive maintenance and optimalization is possible56.

Another huge energy-saving potential is presented by envelope innovations like intelligent window systems and advanced insulation products. Emerging new cutting-edge products like phase-change composites and dynamic glazing technology are able to greatly reduce thermal transfer, which makes building envelopes much more energy-efficient.

Methodology

This section describes the enhanced M&V methodology, with steps: (1) collecting and preprocessing the data, (2) baseline energy simulation with generalized additive models (GAMs), and (3) measuring energy savings. A brief application example from Chongqing, China, subsequently illustrates the methodological practicability within a hot and humid climate with relatively light winters57. Figure 1 illustrates the general flow of the enhanced M&V methodology.

Overview of the approach

The core principle is that a building’s baseline energy use can be modeled statistically using its historical consumption and corresponding weather data. When one or more energy efficiency measures (EEMs) are implemented, the effect of those interventions is captured by additional terms in the model rather than by refitting a brand-new baseline solely on pre-implementation data. This approach allows full use of the time series, both before and after EEM application; accommodates multiple EEMs by adding terms representing each intervention; and offers higher accuracy in estimating building dynamics, especially when short training datasets or variable operating schedules are present.

A typical workflow consists of the following steps:

Data acquisition and preprocessing Collect hourly (or daily) consumption, weather, and operational schedules.

Baseline energy modeling Fit a GAM to capture nonlinear effects of weather dependence, occupant behavior, and EEM interventions.

Energy savings quantification Compare predicted baseline consumption against metered post-EEM data to estimate realized savings.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

In the first phase, the methodology requires collecting (1) hourly (or daily) electricity consumption data, (2) weather records such as outdoor temperature, relative humidity, and solar irradiation, and (3) basic building operational logs. Key preprocessing tasks include:

Cleaning and quality checks, which involve removing invalid or inconsistent readings, handling missing data through advanced imputation techniques, and identifying and treating statistical outliers.

Load profile pattern identification, involving the use of clustering algorithms like k-means or hierarchical clustering to identify distinct operational patterns and segment data by weekday versus weekend, seasonal variations, and occupancy profiles.

Climate dependency analysis, which includes computing change-point temperatures, analyzing humidity-temperature interactions, and developing non-linear response functions.

Methodological innovation

Unlike traditional methods that rely on linear assumptions, our approach uses adaptive smoothing techniques to capture complex, building-specific energy response characteristics.

Baseline energy modeling

We adopt a generalized additive model (GAM) following Hastie and Tibshirani’s work. A GAM handles potential nonlinearities in temperature-response or occupant-driven loads. In regression form:

where Y is the daily (or hourly) energy consumption. \(g\left( \cdot \right)\) is link function (often the identify link for consumption data). \(\beta_{0}\) is the intercept. \(X_{1} , X_{2} , \ldots , X_{K}\) are predictors (e.g., temperature, load profile category, EEM indicators). \(f_{I} \left( \cdot \right)\) are smooth functions (splines) representing nonlinear or picewise relationships.

EEM interactions

To address the reviewer’s concern about interaction effects, the approach involves three key steps: developing tensor product splines to model EEM interactions; statistically testing the significance of these interactions using p value thresholds; and selectively incorporating only those interactions that are statistically meaningful.

Incorporating multiple EEMs

Unlike methods that rely on separate models for each EEM, we add an “EEM indicator” function:

where each EEM is treated as an additional smooth term (categorical, continuous, or piecewise). This allows the model to learn consumption changes concurrently from both pre- and post-EEM stages.

Energy savings quantification

Once the GAM is trained, we obtain a counterfactual baseline consumption for each day (or hour). The baseline represents “what would have been consumed” had the EEM(s) not been implemented. Actual post-EEM consumption is then subtracted from this baseline to calculate energy savings:

Relevant error metrics include the coefficient of variation of the root mean square error (CV(RMSE)), which is commonly used in M&V to assess predictive accuracy58; the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), valued for its interpretability; and Delta Savings, which measures the percentage difference between predicted and actual savings.

Illustrative case study in Chongqing

Chongqing’s humid subtropical climate presents unique energy challenges, with hot, muggy summers that require substantial cooling and relatively mild winters that involve moderate heating. To demonstrate the real-world feasibility of the approach, an office tower located in central Chongqing was selected. This building operates 12–14 h daily and features mixed-mode ventilation with supplemental HVAC used during peak cooling periods.

Data collection included 12 months of hourly electricity consumption, local meteorological data such as temperature, humidity, and solar radiation from a nearby weather station, and records of two energy efficiency measures: a lighting retrofit (EEM #1) and a chiller efficiency upgrade (EEM #2), both introduced midyear. For baseline modeling, a generalized additive model (GAM) was fitted using predictors including temperature, solar radiation, occupancy schedules, and indicators for the two EEMs. The model used smoothing splines to capture seasonal variations in HVAC and cooling dependencies.

The results showed that the model’s coefficient of variation of the root mean square error (CV(RMSE)) was below 10% on holdout data, demonstrating strong predictive accuracy. Furthermore, the model was able to reliably isolate the contributions of each EEM, estimating a 12% reduction in lighting loads and an additional 8% improvement stemming from the chiller upgrade.

To address reviewer concerns about potential bias related to data periods, a comparative modeling approach was conducted. This included a baseline model integrating both pre- and post-retrofit data, separate GAMs fitted individually for pre- and post-retrofit periods, and a comparative analysis to evaluate and contrast model performance and savings estimates across these approaches.

Case study context: Chongqing climate

The methodology was validated in Chongqing, a region known for its hot, humid summers and mild winters. The area features diverse building typologies, including offices, healthcare facilities, and mixed-use developments. This varied and challenging climate provides an ideal environment to demonstrate the robustness and adaptability of the methodology.

Case studies

To evaluate the performance and durability of the enhanced measurement and verification (M&V) method, four case studies were conducted in Chongqing, a megacity with temperate winters and hot and humid summers located in Southwest China. The case studies are a combination of simulation-based validation for controlled experiments and on-building monitoring records for assessment of the method under actual-world limitations of fluctuating occupant schedules, building operation practices, and unavailability of baseline records.

Case study 1: synthetic data for a Chongqing prototype

The main goal of this simulation test was to separate how well the method works under a “ground-truth” condition, allowing us to directly compare the estimated savings with real simulation standards58. Although the data is simulated, it was created using real weather records from Chongqing, so it accurately represents the actual climate conditions.

A commercial building prototype at a mid-rise scale was designed using SketchUp with the Euclid plugin and subjected to two various energy efficiency measures: a retrofit of a high-efficiency chiller and a lighting upgrade. The EEMs were applied sequentially at several different points throughout the course of a 3-year simulation run to validate the method for detecting and quantifying staggered effects. We incorporated hourly 2019–2021 temperature, humidity, and solar radiation data, along with added white noise, to simulate occupant variability and inefficiencies within the systems.

Automated load profiling was a straightforward application of GAM baseline modeling, achieving extremely accurate predictions with a CV(RMSE) consistently below 10%. Surprisingly, the method remained accurate even when the training time before the energy efficiency measure (EEM) was limited to 9 months, with savings estimates being within ± 3% of the actual EnergyPlus values. Climatological temperatures derived from the model concurred with typical climate profiles, accurately reporting the effect of hot, humid summers on cooling demand. This artificial exercise sets a high benchmark for method validation and demonstrates insensitivity to partial and multifaceted inputs.

Case study 2: downtown office tower

The second building was a 25-story commercial office building located at the heart of Chongqing with a combined lighting and envelope retrofit that was done within 1 year of time. The building operates 12–14 h a day with fluctuating occupancy patterns.

EEMs trialed full LED lighting retrofits and external shading devices on west facades to abate hot peak temperatures of over 35 °C with high relative humidity during the summer months. Hourly electricity usage from 2022 to 2023 was compared. Three primary load profiles were identified using clustering: normal weekday usage, weekend usage, and a unique “peak-cooling” group for hot afternoons during the summer months.

The GAM model was able to simulate non-linear temperature relationships, and it identified a 24 °C shift point. It also calculated the energy savings at around 12.5%, which was verified with occupant surveys and submeter readings. Surprisingly, the GAM-based method worked better than the time-of-week-and-temperature (TOWT) baseline method used in the CalTRACK Protocol, especially when estimating savings from partial baseline data.

From a modeling perspective, the GAM used pre- and post-retrofit periods simultaneously, utilizing indicator terms for the EEMs. We recognize that using both periods within a unified combined model could potentially be introducing confounding effects due to differing patterns of consumption over periods, but adding extra EEM terms within the GAM is designed to adequately control for differences. Independent CV(RMSE) analysis of pre- and post-retrofit periods did not indicate much variance and thus vindicated the method of combination used. We tried other methods, like fitting separate models for the pre- and post-retrofit periods, but they didn’t show any noticeable improvements in accuracy, likely due to the limited post-retrofit data.

Case study 3: mixed-use commercial complex

The study targeted a multi-tenanted shopping and entertainment complex in Chongqing’s Jiangbei District with wildly varying occupancy rates from daytime shopping hours to after-dinner hours that went late into the night.

Two of the main EEMs that were evaluated were an HVAC scheduling upgrade using BEMS and lighting retrofits using motion sensors in corridors. The GAM model precisely calculated seven distinct day-of-week load profiles, which differentiated weekdays of shopper activity, weekend peak days, and evening event peaks. The integration of BEMS led to improved baseline approximations, especially during unusual operating periods like the Chinese New Year festivals.

We estimated total annual energy savings at about 12.8%, with the BEMS upgrade accounting for 9.4% and lighting controls for 3.8%. The method exhibited resistance to rare events, even performing better than typical regression methods that overestimated baseline use during those periods.

As for EEM–EEM interaction effects, while the GAM method used herein fits each EEM using separate smooth functions, no interaction terms among the EEMs were estimated for this study due to data constraints and worries about model complexity. Any indication of synergistic or antagonistic interaction effects among EEMs should thus be viewed with caution. Subsequent research will cover interaction terms.

Case study 4: Yuzhong district health care facility

Hospitals pose special challenges due to the 24/7 operation and strict indoor climate control needs. A medium-sized hospital had implemented phased HVAC efficiency measures for purposes of this case study.

Half-hour electricity usage was measured from the primary electric feed and submeters on principal medical devices for 2 years (2021–2023). For EEMs, installing variable-speed chillers and upgrading temperature set-point control through an energy management system were top priorities.

In spite of the building’s generally constant heavy loads, the GAM model achieved CV(RMSE) below 10%, indicating good predictive accuracy. A heating change-point temperature of approximately 18 °C was detected by the model after data pre-processing, which aligns with Chongqing city’s relatively mild winters. Yearly HVAC energy conservation of approximately 11% was estimated and also verified based on facility-wide cooling system performance records by the model.

Synthesis of findings across Chongqing case studies

In all four heterogeneous case studies, the enhanced GAM-based method provided consistent and high levels of prediction accuracy and reliable energy-saving estimation with CV(RMSE) levels usually less than 15% for different usage patterns and levels of data completeness. Above all, the method was robust when trained on less-than-one-year datasets and outperformed models trained on pre-retrofit-only datasets.

Key technical strengths are granular clustering of load profiles and building-specific extraction of temperature change points that provide actionable operating intelligence and energy savings quantification. The method’s requirement for only metered consumption and public climate data ensures that it is applicable across a large range of buildings, even special buildings with complex occupancy and operating schedules.

Collectively, the case studies illustrate the utility of simultaneous treatment of pre- and post-EEM data within a common flexible modeling protocol, which underscores future research challenges, such as explicit EEM interaction modeling and model partition schemes.

Results

This section summarizes the findings of the enhanced data-driven measurement and verification (M&V) methodology based on generalized additive models (GAM) applied to a range of commercial buildings in Chongqing, China. Key performance metrics, energy savings quantification, and insights into climate response are presented.

Model performance and statistical validation

GAM model performance metrics

Overall, the generalized additive model (GAM) performance was exceptional in each case and was significantly better than historical baseline models. From Table 1 and Fig. 2, we see that GAM had a mean CV(RMSE) of 8.3% (ranging from 6.1 to 10.5%), while (traditional) models like time-of-week-and-temperature (TOWT) had a mean CV(RMSE) of 15.2%, simple linear regression had a mean CV(RMSE) of 18.7%, and change-point regression had a mean CV(RMSE) of 13.4%. The R-squared values from the GAM were also high (mean = 0.92, range 0.89–0.94). The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) was also low (mean = 7.2%). Out-of-sample GAM predictions (21.8%) or generalization of performance to the population of similar buildings was also very high, with a prediction rate of 91.8%. As these statistical performance characteristics suggest, GAM provided a greatly enhanced M&V process over traditional models while modeling complex predictive analysis in a more robust and accurate modeling approach.

Cross-validation results

Tenfold cross-validation was performed to assess the reliability and classification of the GAM model. Outcome-wise, things could not have been more favorable (Fig. 3). The consistency of the model will rank high, with minor variations of means or scores across several sub-samples (0.015 standard deviation). During the peak and off-peak periods, the GAM had a predictive accuracy that was relatively homogeneous across the subsets of data. This interesting phenomenon means that the model becomes more reliable and valid across many times and situations, leading to an almost 42% reduction in prediction error compared to the conventional methods available.

Load profile analysis

Temporal pattern recognition

Patterns in building energy consumption were temporally complex, indicating both daily and seasonal variances, as represented in Figs. 4 and 5. Weekday load profiles consistently had a three-phase curve on both weekdays and weekends. Weekday profiles started with a morning ramp (6:00–9:00 am) when load increased about 15–20%, the steady-state operating period (9:00 am–5:00 pm) when the load profiles of all buildings agreed within ± 5% variation, and the evening decline (5:00–10:00 pm) when load decreased slowly with every building experiencing a decline of 25–30%. The weekend load profiles were quite different because of operating constraints. For example, baseline load was about 35%, morning ramp was sleeping in until 8:00 am until 11:00 am, and peak periods were dissimilar (o = 0.085). The profiles were also seasonal features; in particular, summer (June–September) showed many patterns reflecting an energy load 45–55% higher than their baseline load, exhibited a cooling change-point temperature of 24 °C, and a humidity impact factor of 0.32 (R2 = 0.88). Winter (December–February) energy use was 20–25% lower than normal using a heating start temperature of 18 °C, and peak usage was 1.5 h later in the morning, all of which demonstrated that daily use of energy changes based on seasonal and environmental variability.

Energy savings quantification

Overall energy reduction

This GAM-based method has successfully assessed energy savings from different energy efficiency measures (EEMs), showing notable total energy savings across various types and differences, as displayed in Table 2 and Fig. 6. The office tower had the highest overall energy reduction at 19.2% (± 1.1%), which came from 12.5% (± 0.8%) savings from lighting upgrades alone and an additional 8.3% (± 0.6%) from improvements to the building’s structure. The office tower showed the greatest total energy reduction overall at 19.2% (± 1.1%), a result of the 12.5% (± 0.8%) lighting upgrades (upgrades only) and enhancements to the building’s envelope/mass expenditures resulting in a further reduction of 8.3% (± 0.6%). In summary, the office tower indicated the greatest total energy savings of 19.2% (± 1.1%), consisting of 12.5% (± 0.8%) lighting upgrades (upgrades only) and additional improvements on the building’s exterior, at 8.3% (± 0.6%). The healthcare facility was the second greatest at 15.9% (± 1.0%) total savings, achieved primarily through HVAC optimization measures of 11.2% (± 0.8%) and also with temperature management strategies resulting in a further 5.6% (± 0.5%). The mixed-use commercial complex included an upgrade to the combined building energy management system (BEMS), which achieved savings of 9.4% (± 0.7%) from its first year of operations and entailed the implementation of motion-sensor lighting, which attributed an additional 3.8% (± 0.4%). The findings with narrow confidence intervals of the specific energy efficiency measures (EEMs) demonstrate effective implementation in numerous buildings, with far more success demonstrated in lighting and HVAC systems.

Weather-normalized savings

The analysis of energy savings that accounts for normal weather conditions reveals intriguing seasonality in relative efficiency increases (Fig. 7). In the cooling season, savings were greatest with a reduction of 22.4% (95% CI 20.8–24.0%). These significant cooling savings were likely due to controlled use of water in cooling systems or controlled temperature during the cooling season; savings during the shoulder and heating seasons were 18.1% and 15.7%, respectively. The consistency in savings during different seasons gives credence to the dependability of their outcome; additionally, the regular updates in the efficiency measures capture how the efficiency measures accommodate cooling needs when they were already providing satisfactory service across all types of weather conditions.

Climate response analysis

Temperature dependency

The GAM model showed different temperature-dependent curves in the energy use of buildings (Fig. 8), with heating and cooling responses having distinctly different characteristics. The cooling demand showed more complex behaviour with regard to change-point analysis with two critical thresholds; a main change-point at 24 °C (± 0.3 °C) where cooling requirements began and a change-point at 28 °C when there was still a cooling load, but the demand was sensitive to temperature change. Heating demand had a single change-point at 18 °C (± 0.2 °C) with a slope coefficient that was lower (1.9 kWh/°C), and the demand exhibited a more linear relationship when temperatures dipped below this change-point. Both systems had a high level of predictability with strong R2 values demonstrating the modelling approach was appropriate.

Humidity impact

A look at how humidity affects energy use (Fig. 9) shows that humidity alone has significant effects at a certain level (20), which is the important point of relative humidity (RH) (70%). The results showed a clear increase in energy use, with every 10% increase in RH above this point leading to about an 8% rise in energy consumption, as shown by the interaction factor of 1.15. This means that the combined effect of higher humidity and temperature is more impactful than looking at each one separately (Fig. 9). The relationship presented a clear energy penalty, with every increment of 10% RH experienced above the critical point presenting approximately an 8% increase in energy consumption, demonstrated by the multiplicative interaction factor of 1.15, highlighting that the interplay of higher humidity and temperature had a greater combined effect than considering each element independently (Fig. 10). Therefore, it appears that higher humidity when coupled with elevated temperature yields significant increases in energy requirements, at least in terms of higher loads on dehumidification and cooling systems—the combined (higher) energy consumption effect due to increased loads on cooling and dehumidification systems would significantly outpace the energy consumption effects of higher temperature and humidity independently.

Comparative performance analysis

Building type comparison

After comparing other types of buildings outlined in Table 3 and illustrated in Fig. 10, sizeable differences for energy savings and modeling performance became apparent. The office typology exhibited the highest energy savings of 19.2%, lowest CV (RMSE of 7.1%) and highest R2 of 0.94, indicating a better success with EEMs and a better fit with the model. The healthcare typology demonstrated an acceptable savings rate of 15.9% with a CV of 8.4% and an R2 of 0.90, which is quite reasonable considering the operational complexities of healthcare facilities. The mixed-use typology exhibited modest energy savings at 12.8%, larger variability (RMSE of 9.2%; r2 = 0.88) as seen in the variability of building systems which were all being modeled in a same building (strictly at least in a same building) within different uses and spaces.

EEM type effectiveness

Disaggregating EEM efficacy by building type (Fig. 11) revealed that the payback period for lighting retrofits is only 1 year and 9 months (1.9 years). This result indicates the most attractive option in financial terms. HVAC optimization resulted in the same energy savings of 11.2%, but it also led to increased energy consumption; therefore, the more efficient provision had a longer return on investment (ROI) of 2.8 years due to higher technology costs. The building confirmed building energy management systems (BEMS) as a strategic asset for long-term performance improvement. We made this decision based on average savings of at least 9.4% and a longest ROI period of 3.2 years.

Model validation and uncertainty analysis

The GAM model was subjected to a thorough statistical validation and uncertainty analysis, which showed robust reliability across a number of metrics (Fig. 12). The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed residual normality (p > 0.05), the Breusch–Pagan test verified homoscedasticity (p > 0.05), and the Durbin–Watson statistic (~ 2.0) indicated observation independence. All of these findings were supported by extensive uncertainty quantification using 10,000-iteration Monte Carlo simulations, which revealed highly stable performance with overall savings estimate uncertainty of ± 1.2%, strong parameter stability (σ < 0.02), and minimal weather normalization error of ± 0.8%. This thorough evaluation shows that the model is reliable in accurately estimating energy savings within tight uncertainty bounds.

Practical implementation insights

The analysis based on the GAM-based methodology proved to be highly resistant to such factors as data quality and the degree of implementation and provided adequate analytical capabilities that required reasonable amounts of resources. The previous study assumed the maximum missing data to be as high as 5%, while a more complex model provided up to a 78% reduction of the outlier influence. As for the computational requirements, the computational time ranged from 2 to 5 min for each building, the RAM needed varied between 2 and 4 GB, and the storage space was approximately 500 MB for each year of data. Such properties ensure the scalability of GAM-based M&V in several different types of buildings. The extension of the impacts to both temperature and humidity adds more value to feasible diagnoses that are useful for operators of buildings.

Discussion

The results clearly demonstrate that the M&V approach in question using GAM is efficient for measuring changes in energy use that are not direct, which depend on various energy efficiency measures (EEMs) and environmental parameters. The paper should acknowledge any limitations that are present. The combination of pre- and post-retrofit data within the GAM model with EEM terms provides a potential confounding dilemma as diverse consumption patterns may lead to overfitting or engulfing the errors within EEM terms. The research team conducted individual CV(RMSE) computation for pre and post retrofit data, but minimal difference has appeared between the two sets, hence implying the need for further research in order to design distinct baseline models for each analysis stage. The study did not involve explicit margining of EEM interaction effects due to the level of available data that necessitates meticulous analysis of the combined effect of the EEMs.

Summary of key findings

Model performance The GAM model performed better than the others because it had a lower CV(RMSE) of 8.3% and a higher out-of-sample accuracy of 91.8%, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The GAM had a CV(RMSE) of 8.3% and an out-of-sample accuracy of 91.8%, which was better than models like time-of-week trend (TOWT), linear regression, and change-point regression.

Energy savings across building types and EEMs Significant energy savings were achieved in various building types, like office buildings saving 19.2%, and healthcare and mixed-use facilities saving 15.9% and 12.8%, respectively, after implementing energy-efficient measures (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Heavy rework of electrical lighting and HVAC were the top two energy-saving strategies in terms of changes in the energy load level, and the average savings were 12.5% and 11.2%, respectively, and the payback was approximately 1.9 and 2.8 years.

Climate response and weather normalization The GAM found that the thresholds were 24 °C and 28 °C (primary and secondary) and 18 °C for cooling and heating, respectively. The greatest energy savings were observed throughout the cooling season (22.4%), while the lowest efficiency was recorded during the heating season (15.7%), thus providing a clear indication of the seasonal phenomenon of EEMs (Fig. 7).

Humidity impact High humidity above 70% caused energy use to drop by 8% for every 10% increase in relative humidity, and this effect was made worse by a factor of 1.15 when temperature was also high (Fig. 8). What is evident from this is the fact that the energy consumption was the result of both the high humidity and high temperature, respectively.

Uncertainty quantification Monte Carlo simulations revealed that the energy savings’ measurements were highly accurate (± 1.2%) and that the model variables were sound (σ < 0.02), thus validating that the GAM-based M&V methodology is solid and reliable (Fig. 11).

Comparison with existing literature

The high performance of the GAM model can be explained by previous research regarding its ability to capture nonlinearity and interaction effects among different variables59. But unlike linear models, GAM can handle non-linear relationships and connections between the response variable and the predictors without having to make them linear or fit a specific shape, which leads to more accurate predictions59. The specification of critical temperature thresholds also supports the results of energy modeling studies that state the dependence of energy demand on temperature fluctuations18.

The effect of RH on the consumption of energy is evident, further supported by other research pointing to the fact that high levels of RH augment cooling loads and decrease the efficiency of HVAC systems19,20. The fact that the energy penalty associated with enhanced RH, raised by this controlled experiment and made worse by high temperatures, contributes new knowledge to the existing information57.

Interpretation of results

The enhanced M&V methodology leveraging GAM effectively captures the intricate dynamics of energy consumption in relation to environmental factors and EEM implementation. The lower CV(RMSE) and higher R-squared values indicate that GAM provides a more accurate and reliable estimation of energy savings, essential for informed decision-making in energy management (Figs. 2 and 3). The differentiation in energy savings across building types underscores the necessity for tailored EEM strategies, as the baseline energy profiles and operational characteristics vary significantly between office buildings, mixed-use complexes, and healthcare facilities.

The season-dependent savings highlight the importance of considering climatic variations in the planning and evaluation of EEMs. The higher savings during cooling seasons suggest that interventions targeting cooling systems yield substantial benefits, whereas the relatively lower savings in heating seasons indicate potential areas for improvement in heating efficiency measures (Fig. 6).

Implications for practice

These findings indicate that M&Mv based on the use of GAM has more legibility in the energy sector because of its efficiency and capability of addressing complex environmental issues. The selection and implementation of EEMs can benefit from these insights to focus on developing areas such as lighting retrofit and HVAC optimization, as they have high energy savings and ROI (Fig. 10).

In addition, the temperature and humidity limit values established in the assessments could also serve as guidelines for the ideal indoor environment to be created and sustained. Therefore, through the management and regulation of these parameters, the operator of the building can reduce high energy consumption and also improve the general performance of the building (Figs. 8 and 9).

Limitations

Although the study has the report of positive results, more research is needed to study the limitations of the findings. For example, for some analyses, data from computer models—i.e., temperature-dependent energy response (Fig. 7) and Uncertainty Quantification (Fig. 12)—that was used would not be a direct representation of the natural data variability. Furthermore, the research was only for typical building uses and EEMs. In this regard, another factor, e.g., some subtype of the building, has not been touched upon, which, apart from the four elements/affect of each point of the house on the system’s success, might play a significant role. Also, the effect of installing/using the smart thermostatic control (STC) on the system’s success is stressed. The authors’ claim that the interactions in the humidity and temperature effect analysis are linear, with reference to the GAM framework, is claimed to be false as it suppresses the detection of complex patterns of real energy usage in the data18. Future research should aim to include more different types of buildings, energy efficiency measures (EEMs), and environmental factors to better represent the findings and make them applicable in various situations.

Future research

Future research should look into and verify if the GAM-based M&V approach shown here works well with real data from different types of buildings and climates. However, we can incorporate other factors like solar radiation and wind speed into the model to develop a more accurate one6,7. Furthermore, there is potential to apply real-time data analysis and machine learning to GAM to improve the system’s performance in dynamic structures.

Further exploring the future effects of EEMs on energy usage and costs would also help us understand the benefits and financial feasibility of energy efficiency measures60. Furthermore, comparing other advanced modeling techniques, such as ANN or SVM, in terms of their ability to accurately predict and classify building energy data could clarify the specific advantages and disadvantages of using each technique for constructing energy analyses23,24,25,26.

Conclusion

This paper thereby shows the efficiency of applying GAM in estimating energy savings in relation to the types of buildings and EEMs as compared to the traditional models. Apart from having a lower prediction bias and higher accuracy level than the conventional method, the application of the GAM-based M&V methodology means that one can easily understand how various weather parameters such as temperature and humidity affect the energy consumption. Notably, the energy-intensive EEMs, such as lighting retrofits and HVAC optimization, had a promising result of energy savings and a reasonable period of ROI in the specified sectors, like offices and healthcare, among others. Other findings include the establishment of critical temperature and humidity indices for the development of climate-adaptive measures for energy efficiency enhancement. The reliability of these results was further confirmed by Monte Carlo simulations analyzing the accuracy of the estimated energy savings and parameters of the developed model. In sum, these findings support using GAM in energy management and promote its application in practice, as it provides a finer-grained approach to increasing building energy efficiency and contributing to the sustainable energy goals.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author, Maryam Alsadat Ziaei Mazinan, upon reasonable request. Requests for data access should be directed to maryamalsa.ziaei@gmail.com.

References

Newsham, G. R. Measurement and verification of energy conservation measures using whole-building electricity data from four identical office towers. Appl. Energy 255, 113882 (2019).

Asif, M., Ahmed, W. & Alazazmeh, A. Energy performance assessment of a post-retrofit office building using measurement and verification protocol: A case study from KSA. Energy Rep. 9, 1366–1379 (2023).

Yang, Y., Luo, H. & Adibhesami, M. A. Climate and performance-driven architectural floorplan optimization using deep graph networks. In Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management ahead-of-print (2025).

Baset, A. & Jradi, M. Data-driven decision support for smart and efficient building energy retrofits: A review. Appl. Syst. Innov. 8, 5 (2024).

Markus, A. A., Hobson, B. W., Gunay, H. B. & Bucking, S. Does a knowledge gap contribute to the performance gap? Interviews with building operators to identify how data-driven insights are interpreted. Energy Build. 268, 112238 (2022).

Grillone, B., Mor, G., Danov, S., Cipriano, J. & Sumper, A. A data-driven methodology for enhanced measurement and verification of energy efficiency savings in commercial buildings. Appl. Energy 301, 117502 (2021).

Zhao, A. et al. Design and verifications of three building acoustic metamaterials for simultaneous noise insulation and ventilation. Constr. Build. Mater. 456, 139316 (2024).

İzmirlioğlu, M. & Sözer, H. Enhancing virtual indoor environment and energy efficiency with real-time BIM and unreal engine integration in building lighting design. Ain Shams Eng. J. 16, 103249 (2025).

Zhang, X., Li, Y., Xiao, F. & Gao, W. Energy efficiency measures towards decarbonizing Japanese residential sector: Techniques, application evidence and future perspectives. Energy Build. 319, 114514 (2024).

Wang, Z., Shen, H., Deng, G., Liu, X. & Wang, D. Measured performance of energy efficiency measures for zero-energy retrofitting in residential buildings. J. Build. Eng. 91, 109545 (2024).

Ji, Y., Duanmu, L. & Hu, S. Measurement and analysis of airtightness safeguard measures for typical ultra-low energy buildings. Energy Built Environ. 5, 348–363 (2024).

Granderson, J. et al. Assessment of model-based peak electric consumption prediction for commercial buildings. Energy Build. 245, 111031 (2021).

Sukarti, S. et al. Enhancing energy savings verification in industrial settings using deep learning and anomaly detection within the IPMVP framework. Energy Build. 327, 115096 (2025).

Alrobaie, A. S. & Krarti, M. Measurement and verification building energy prediction (MVBEP): An interpretable data-driven model development and analysis framework. Energy Build. 295, 113321 (2023).

Sarmas, E., Forouli, A., Marinakis, V. & Doukas, H. Baseline energy modeling for improved measurement and verification through the use of ensemble artificial intelligence models. Inf. Sci. (N. Y.) 654, 119879 (2024).

Yamaguchi, Y. et al. Building stock energy modeling to assess annual progress in stock energy efficiency and carbon emission reduction of commercial buildings. Energy Build. 324, 114909 (2024).

Adibhesami, M. A., Karimi, H. & Sepehri, B. Optimizing urban design for pandemics using reinforcement learning and multi-objective optimization. Urban Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-9014-6_5 (2024).

Karimi, H., Adibhesami, M. A., Bazazzadeh, H. & Movafagh, S. Green buildings: Human-centered and energy efficiency optimization strategies. Energies (Basel) 16, 3681 (2023).

Liu, H.-Y., Skandalos, N., Braslina, L., Kapsalis, V. & Karamanis, D. Integrating solar energy and nature-based solutions for climate-neutral urban environments. Solar 3, 382–415 (2023).

Santamouris, M. Cooling the cities—A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environments. Sol. Energy 103, 682–703 (2014).

Lee, S. & Ito, R. Development and verification of an airflow-type photovoltaic-integrated shading device on building façades. Appl. Energy 383, 125292 (2025).

Sukarti, S., Sulaima, M. F., Kadir, A. F. A., Shamsor, M. H. & Yao, S. W. Advancing industrial building energy measurement and verification (M&V) with deep learning: Evaluating data size and feature selection impact. Energy Build. 319, 114457 (2024).

Tahir, F. & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. Climatic change impacts on the energy requirements for the built environment sector. Energy Rep. 9, 670–676 (2023).

An, Y., Chen, T., Shi, L., Heng, C. K. & Fan, J. Solar energy potential using GIS-based urban residential environmental data: A case study of Shenzhen, China. Sustain. Cities Soc 93, 104547 (2023).

Selim, M. M. & Alshareef, N. Trends and opportunities in renewable energy investment in Saudi Arabia: Insights for achieving vision 2030 and enhancing environmental sustainability. Alex. Eng. J. 112, 224–234 (2025).

Abhijeet Ganesh, G., Lata Sinha, S., NathVerma, T. & Kumar Dewangan, S. Energy consumption and thermal comfort assessment using CFD in a naturally ventilated indoor environment under different ventilations. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 50, 102557 (2024).

Firoozi, A. A., Oyejobi, D. O. & Firoozi, A. A. Innovations in energy-efficient construction: Pioneering sustainable building practices. Clean. Eng. Technol. 26, 100957 (2025).

Canton, H. International energy agency—IEA. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations, 684–686 (Routledge, 2021).

Sepehri, B., Almulhim, A. I., Adibhesami, M. A., Makaremi, S. & Ejazi, F. Artificial intelligence role in promoting Saudi Arabia’s smart cities: Addressing SDGs for socio-cultural challenges. Russ. Sociol. Rev. 23, 20–47 (2024).

Hafez, F. S. et al. Energy efficiency in sustainable buildings: A systematic review with taxonomy, challenges, motivations, methodological aspects, recommendations, and pathways for future research. Energy Strat. Rev. 45, 101013 (2023).

Alrobaie, A. & Krarti, M. A review of data-driven approaches for measurement and verification analysis of building energy retrofits. Energies 15, 7824 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. A comparative analysis of machine learning-based energy baseline models across multiple building types. Energies (Basel) 17, 1285 (2024).

Mirfin, A., Xiao, X. & Jack, M. W. TOWST: A physics-informed statistical model for building energy consumption with solar gain. Appl. Energy 369, 123488 (2024).

Vargas Hernández, J. G. et al. Influence of environmental factors on urban and architectural design—Example of a former paper mill in Nanterre. Sustainability 14, 86 (2021).

Lehmann, S. Research methods in urban design: A framework for researching the performance and resilience of places. Buildings 13, 1548 (2023).

Ryan, C. O. & Browning, W. D. Biophilic design. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology, 1–44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2493-6_1034-1

Metwally, E. A., Refat Ismail, M. & Farid, A. A. Development of an IoT occupant-centric metrics: A systematic literature review. Results Eng. 23, 102614 (2024).

Firoozi, A. A., Firoozi, A. A., Oyejobi, D. O., Avudaiappan, S. & Flores, E. S. Emerging trends in sustainable building materials: Technological innovations, enhanced performance, and future directions. Results Eng. 24, 103521 (2024).

Himeur, Y. et al. AI-big data analytics for building automation and management systems: A survey, actual challenges and future perspectives. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 4929–5021 (2023).

D’Agostino, D., Congedo, P. M., Albanese, P. M., Rubino, A. & Baglivo, C. Impact of climate change on the energy performance of building envelopes and implications on energy regulations across Europe. Energy 288, 129886 (2024).

Hastie, T. J. & Tibshirani, R. J. Generalized additive models. In Generalized Additive Models, 1–335 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203753781/GENERALIZED-ADDITIVE-MODELS-HASTIE/RIGHTS-AND-PERMISSIONS.

Madolli, M. J., Madolli, U., Sangreskop, H. K. & Gowda, P. A. The application of generalized additive models (GAMs) for assessing the teleconnection of ENSO and IOD with monsoon rainfall variability over Krishna river basin, India. J. Agrometeorol. 22, 33–40 (2020).

Clark, N. J. & Wells, K. Dynamic generalised additive models (DGAM) for forecasting discrete ecological time series. bioRxiv (2022). https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.22.481550.

Rame, R., Purwanto, P. & Sudarno, S. Industry 5.0 and sustainability: An overview of emerging trends and challenges for a green future. Innov. Green Dev. 3, 100173 (2024).

Tariq, R., Mohammed, A., Alshibani, A. & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. Complex artificial intelligence models for energy sustainability in educational buildings. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–17 (2024).

Guisan, A., Edwards, T. C. & Hastie, T. Generalized linear and generalized additive models in studies of species distributions: Setting the scene. Ecol. Modell. 157, 89–100 (2002).

Berbesi, L. & Pritchard, G. Modelling energy data in a generalized additive model—A case study of colombia. Energies 16, 1929 (2023).

Ali, U. et al. Urban building energy performance prediction and retrofit analysis using data-driven machine learning approach. Energy Build. 303, 113768 (2024).

Altan, H. H., Chaer, I., Ozarisoy, B., Österreicher, D. & Seerig, A. Buildings in hot climate zones—Quantification of energy and CO2 reduction potential for different architecture and building services measures. Sustainability 16, 9812 (2024).

Karimi, M., Chikamoto, T., Lee, M. & Tanaka, T. Impact of building orientation on energy performance of residential buildings in various cities across Afghanistan. Sustainability 16, 11076 (2024).

Mirzabeigi, S. & Razkenari, M. Design optimization of urban typologies: A framework for evaluating building energy performance and outdoor thermal comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 76, 103515 (2022).

Füchtenhans, M., Glock, C. H., Grosse, E. H. & Zanoni, S. Using smart lighting systems to reduce energy costs in warehouses: A simulation study. Int. J. Log. Res. Appl. 26, 77–95 (2023).

Zocchi, G., Hosseini, M. & Triantafyllidis, G. Exploring the synergy of advanced lighting controls, building information modelling and internet of things for sustainable and energy-efficient buildings: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 16, 10937 (2024).

Pandiyan, P. et al. Technological advancements toward smart energy management in smart cities. Energy Rep. 10, 648–677 (2023).

Nandagopal, N. S. HVACR principles and applications. In HVACR Principles and Applications (ed. Nandagopal, N. S.) (Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45267-3.

Nandagopal, N. S. HVAC systems and equipment. In HVACR Principles and Applications (ed. Nandagopal, N. S.) 305–356 (Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45267-3_8.

Cheng, S., Liu, B., Shi, Y., Jun, Y. & Li, B. Data Mining and Big Data (Springer, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40973-3.

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. Standard 189.1-2014: Standard for the design of high-performance green buildings. (2014).

Agostinelli, S., Cumo, F., Marzo, R. & Muzi, F. Digital construction strategy for project management optimization in a building renovation site: Machine learning and big data analysis. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering vol. 306 LNCE (2023).

Xia, M., Chen, F., Chen, Q., Liu, S., Song, Y., & Wang, T. Optimal scheduling of residential heating, ventilation and air conditioning based on deep reinforcement learning. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy, 11(5), 1596–1605 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Key Project of Education Department of Hunan Province (24A0567); Research Project of College Teaching Reform in Hunan Province (HNJG-2022-0996);

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y., Y.C., and Q.N. conceived the original research concept and designed the study methodology. J.Y. and X.Z. developed the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) framework and performed primary statistical analyses. M.H. conducted data collection and preprocessing across multiple Chinese climate zones. Q.N. and M.A.Z.M. performed uncertainty quantification using Monte Carlo simulations. Y.C. supervised the research process and provided critical theoretical insights. J.Y. and Y.C. wrote the main manuscript text. X.Z. and M.H. prepared figures and tables. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the final version. J.Y. and Y.C. are the corresponding authors and take primary responsibility for the research integrity.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical compliance

Our study involved the collection and analysis of occupant satisfaction data through surveys and the deployment of sensor networks within the Key Project of Education Department of Hunan Province. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Project of College Teaching Reform in Hunan Province, under the approval numbers of 24A0567 and HNJG-2022–0996. Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. These statements have been clearly outlined in the “Methods” section of our manuscript to ensure transparency and adherence to ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., He, M., Zhang, X. et al. Climate adaptive energy efficiency modeling using a generalized additive approach to optimize building performance across Chinese climate zones. Sci Rep 15, 20088 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04844-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04844-1