Abstract

Improving growth performance is vital in poultry production. Although several studies have established associations between gut microbiota and growth, the direct impacts remain unclear. A total of 120 1-day-old Sansui ducks were randomly assigned to the FMT and CON groups. From the 1st day, ducks in the FMT group were orally administrated with 0.5 mL fecal microbiota suspension for three consecutive days, while sterile PBS solution was used as a substitute in the CON group. The results revealed that FMT improved average daily gain (ADG) (P < 0.001) and body weight (BW) (P < 0.001), with a tendency for a better feed conversion rate (FCR) (P = 0.062). LEfSe analysis indicated a significant increase in the abundance of the Lactobacillus (P < 0.001), Bifidobacterium (P = 0.006), Megamonas (P = 0.008), and Subdoligranulum (P = 0.005) in the FMT group. Similarly, the phyla Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was higher in the FMT group compared to the CON group. Additionally, the ACE, Chao, and Shannon indices were also significantly higher in the FMT group (P < 0.001). To sum up, FMT enhanced growth performance, which could be associated with reducing proinflammatory pathogen colonization in the duck cecum. This modulating effect likely results from increased microbial diversity and the enrichment of beneficial bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the gut microbiome, frequently called a “microbial organ,” has garnered significant research attention due to its symbiotic relationship with host health and critical roles in nutrient digestion and absorption, immune system development, and protection against pathogens1,2,3. Maintaining a balanced intestinal microbiota benefits the host by inhibiting pathogen colonization, enhancing intestinal barrier integrity, supporting normal nutrient metabolism, and fostering the proliferation of commensal microbes4. Moreover, the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in breaking down various food components and nutrients and synthesizing a range of metabolites that interact with the host5,6. The gut microbiota is a diverse and complex community of microorganisms that colonizes ducks’ gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with the cecum exhibiting the highest microbial diversity and dynamic population7,8. Research on the duck cecum has consistently emphasized the role of gut microbiota in enhancing feed digestion, nutrient absorption, host defense, and immune function3,7,8,9. A stable gut microbiota supports the host by preventing colonization, facilitating pathogen clearance, and enhancing growth performance10.

Notably, over the past decade, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and probiotic supplementation have emerged as promising therapeutic and preventive approaches for reestablishing intestinal microbiota, mitigating inflammatory responses, and promoting growth and development11,12. For instance, transferring fecal microbiota from healthy chickens could influence the early establishment of gut microbiota in recipient chicks, potentially leading to long-term effects on host-microbe interactions and development13. It is reassuring that FMT has shown potential in enhancing weight gain and pathogen resistance in broilers14. Glendinning et al.15 demonstrated that transplanting cecal microbiota from Roslin broilers to different chicken breeds during the first week of life increased the richness and diversity of microbiota in the recipients. Furthermore, early colonization of harmful bacteria induces intestinal inflammation through the TLR4 and NF-κB pathways, while FMT could reduce inflammation and improve bird growth performance16.

Manipulating gut microbiota through FMT or probiotics has been demonstrated to influence chicken growth and development. For instance, transferring fecal microbiota from 30-day-old chickens with high feed efficiency to newly hatched chicks has increased feed intake and body weight in female chickens17. Similarly, administering fecal microbiota from chickens with high feed conversion ratios affects early gut microbiota colonization, intestinal permeability, gut morphology, and innate immune responses in recipients18. Probiotic supplementation, comprising strains such as Lactobacillus reuteri, Bacillus subtilis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, has improved plasma immunoglobulin levels and enhanced growth performance in chickens19.

Moreover, gut microbes produce diverse metabolites derived from dietary components or endogenous substrates, which mediate host-microbiota communication, particularly at the microbiota-mucosal interface20. Alterations in gut microbiota composition are often accompanied by changes in microbial metabolites and their interactions with gut epithelial cells. For example, dietary fiber supports the growth of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) producing bacteria, and the SCFAs, especially butyrate, serve as an energy source for gut epithelial cells, promoting their growth and function21. This study investigated the effects of fecal microbiota on the growth performance of Sansui ducks using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. We aimed to integrate FMT into the management of duck production, presenting a novel approach to improving duck growth performance.

Materials and methods

Experimental conditions

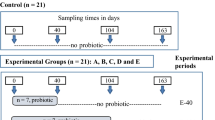

A total of 120 1-day-old Sansui ducks were selected and randomly divided into two groups: a control (CON) group (n = 60) and a fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) group (n = 60); each group comprised four replicates. The ducks were distributed into ten cages (0.65 m H × 0.8 m W × 1.2 m D), and the experiment lasted 42 days. The initial temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1 °C, with a systematic weekly reduction of 2 °C until ambient room temperature was achieved. Humidity levels were sustained between 65–70%, and a light–dark cycle of 23:1 was implemented. The duck house was cleaned each morning and disinfected daily with a 5% sodium hypochlorite solution. From the 1st day, ducks in the FMT group orally received fecal suspension with 0.5 mL every afternoon for 3 days. Ducks in the CON group orally received PBS with 0.5 mL, and the ducks had free access to feed and water during the experiment. The ingredients and nutrient composition of the experimental diets are shown in Table 1.

Preparation of fecal microbiota suspension

Six 42-day-old healthy female Sansui ducks with the same genetic background (Purchased from Sansui County, Guizhou) were selected as fecal donors. Once the donor ducks defecated in the morning, the excreta’s white part was removed immediately because it mainly comprised of uric acid. Feces with 15 g were collected daily in a sterile tube (50 mL), homogenized in 150 mL of sterile PBS, and centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 r.p.m., 4 °C. The mixture was kept on ice until the precipitates were fully settled, and the supernatant was collected and filtered with sterile gauze to get fecal suspension. The microbial suspensions were stored at -80 °C until used for FMT.

Sample collection and growth performance

Feed consumption was monitored on experimental days 1, 14, and 28 for each group. The average daily feed intake (ADFI), body weight (BW), average daily gain (ADG), and feed conversion rate (FCR) for each replicate were then computed. At 42 days into the feeding study, we randomly selected two birds from each replicate, which were euthanized through cervical dislocation following a 12 h feed deprivation, and their cecal contents samples were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C for subsequent analysis.

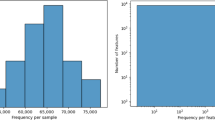

Microbial genomic DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

The cecal contents were used from 200 mg samples using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 16 samples were used for 16S rDNA sequencing, eight samples per group. The hypervariable regions V3-V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified with the forward primer 357F (5ʹ-ACTCCTACGGRAGGCAGCAG-3ʹ) and reverse primer 806R (5ʹ-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3ʹ). DNA sequencing was performed on a Novaseq sequencer (Illumina) with services from TinyGene Bio-Tech.

The PCR reaction was set up in a 50 µL mixture containing 1–2 µL of DNA, 200 µM dNTPs, 0.2 µM primers, 10 µL of 5X buffer, and 1 U Phusion DNA Polymerase. The amplification program included an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s), and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. After PCR, barcoded products were purified using a DNA gel extraction kit (Axygen) and quantified with an FTC-3000 PCR system. For the second PCR, dual barcodes were added, and amplification conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by eight cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s), and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The library was purified and sequenced with paired-end reads on the Novaseq platform.

Sequencing data analysis

The raw 16S rRNA gene sequencing reads were demultiplexed according to their barcodes. All paired-end (PE) reads were processed with Trimmomatic (version 0.35) to eliminate low-quality bases, applying the parameters (SLIDING WINDOW: 50:20, MINLEN: 50). Subsequently, the trimmed reads were merged using the FLASH program (version 1.2.11) with default settings. Low-quality contigs were discarded via the screen.seqs command, using the following criteria: maxambig = 0, minlength = 200, maxlength = 485, and maxhomop = 8.

For 16S sequence analysis, a combination of software tools was employed: Mothur (version 1.33.3), UPARSE (search version v8.1.1756, http://drive5.com/uparse), and R (version 3.6.3). The demultiplexed reads were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% sequence identity, and singleton OTUs were removed using the UPARSE pipeline (http://drive5.com/usearch/manual/uparse_cmds.html). With the classification, the taxonomic assignment of OTU representative sequences was performed against the Silva 128 database, using a confidence threshold of ≥ 0.6. Seqs command in Mothur. OTU taxonomies, ranging from phylum to species, were determined based on the NCBI database. For the analysis of alpha diversity, indices including Shannon, Chao, ACE, and rarefaction curves were calculated using Mothur and visualized with R. Beta diversity was assessed by calculating the weighted and unweighted UniFrac distance matrices using Mothur, with visualization performed through Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) using the ape package in R, Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was performed using the vegan package in R and hierarchical clustering using the end extend package in R. The Bray–Curtis and Jaccard metrics were calculated with the vegan package in R and visualized similarly to the UniFrac analysis. R and hierarchical clustering via the end extend package in R. Additionally, Bray–Curtis and Jaccard metrics were calculated with the vegan package in R and visualized in the same manner as the UniFrac analysis. Lastly, the bacterial taxonomic differences between the FMT and CON groups were analyzed using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and tabulated separately for each treatment. First, a normality test was performed to assess the distribution of the data. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software for Windows (Version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way ANOVA was applied to compare more than two groups, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison test. An unpaired two-tailed t-test was used to compare the two groups. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

FMT improves the growth performance of Sansui ducks

The growth performance of ducks was significantly enhanced following FMT treatment compared to the CON group. Specifically, during 1–14 days, the ADG in the FMT group was significantly increased (P < 0.001) compared to the CON group (Fig. 1a,b), and this improvement continued during the 15–28 day period, with a similarly significant increase (P < 0.001). Moreover, BW in the FMT group was markedly higher (P < 0.001) than that of the CON group during both the 1–14 and 15–28 days (Fig. 1c,d). Although the feed conversion rate was not significant (P > 0.05), there was a linear increasing trend in which the FMT group exhibited a lower FCR (P = 0.062) over the entire 1–28 day period (Fig. 1e).

Effects of FMT on the growth performance in Sansui ducks. (a) Average daily gain from 1 to 14 days, (b) Average daily gain from 15 to 28 days, (c) Body weight from 1 to 14 days (d) Body weight from 15 to 28 days, (e) Feed conversion rate from 1 to 28 days. Abbreviations: ADG = Average daily gain, BW = Body weight, FCR = Feed conversion rate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

FMT changes the composition of cecal microbiota

To investigate the effects of FMT on the community composition of cecal microbiota in ducks, we utilized 16S rRNA sequencing and comprehensive microbiome analysis. Microbiome analysis revealed changes in the composition of the phylum and genus in the cecum (Fig. 2). Specifically, at the phylum level (Fig. 2a), Firmicutes and Bacteroides were the two phyla that accounted for the proportions, and Actinobacteria were an enriched bacterium in the FMT group (P = 0.039). In contrast, the average abundance of Proteobacteria was lower than that of the CON group (P > 0.05). Remarkably, the phyla Firmicutes / Bacteroidetes ratio in the FMT group was higher than in the CON group (P > 0.05). At the genus level (Fig. 2b), the top 3 abundant bacteria in the FMT group were Bacteroides (25.71%), Fusobacterium (7.42%), and Alistipes (3.18%). In comparison, the CON group was Bacteroides (30.20%), Fusobacterium (5.48%), and Alistipes (4.74%). Additionally, as demonstrated through principal component analysis (PCA) analyses, the beta diversity in the FMT group had no significant differences in the cecum compared with the CON group (Fig. 2c).

FMT alters the alpha diversity of the cecal microbiota and enriches specific bacterial populations

As illustrated in Fig. 3a, FMT significantly enriched the alpha diversity of the cecum microbiota, as evidenced by significantly higher values in the FMT group of the ACE (P < 0.001), Chao (P < 0.001), and Shannon (P < 0.001) indices compared to the CON group. Notably, FMT significantly enriched core bacterial genera (Fig. 3b), including Lactobacillus (P < 0.001), Bifidobacterium (P = 0.006), Megamonas (P = 0.008), and Subdoligranulum (P = 0.005). Likewise, evident from the taxonomic cladogram obtained by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) (Fig. 3c,d), LEfSe identified signature genera associated with FMT treatment, which include Peptococcus, Faecalitalea, Streptococcus, and Turicibacter. In addition, FMT increased the abundance of the class Coriobacteriia. Particularly, the orders of Lactobacillales, Bifidobacteriales, Selenomonadales, and Coriobacteriales were spotlighted, with an increase in the families Bifidobacteriaceae, Peptococcaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, and Enterococcaceae. Similarly, at the species level, FMT significantly augmented the abundance of Lactobacillus influviei, Ruminococcaceae bacterium, Enterococcus cecorum, Faecalococcus pleomorphus, and Veillonella magna. Conversely, FMT led to a decrease in the abundance of the genera Rikenella, Epsilonproteobacteria, Sutterella, Collinsella tanakaei, Helicobacteraceae, Mucispirillum, and Deferribacterales. These differences were evident in the core microbiota compositions in the FMT and CON groups.

FMT alters the alpha diversity of the cecal microbiota and enriches specific bacterial populations. (a) Alpha diversity analysis of cecal microbiota, including ACE, Chao, and Shannon indices, (b) Differential analysis of core microbial genera in cucum, (c,d) The taxonomic cladogram obtained by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Correlations between cecal microbiota and growth performance

To explore the correlation between the abundance of the genus in the cecum and duck growth performance, a Spearman correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the potential link between alterations in gut microbiota composition and growth performance in ducks (Fig. 4). The genera Megamonas (r = 0.633; P = 0.009), Subdoligranulum (r = 0.668; P = 0.005), and Lactobacillus (r = 0.553; P = 0.026) were positively correlated with growth performance, but genera Oscillospira (r = − 0.505; P = 0.046), Mucispirillum (r = − 0.638; P = 0.008), Sutterella (r = − 0.548; P = 0.028), and Anaerobiospirillum (r = − 0.581; P = 0.018) were negatively correlated with growth performance.

Discussion

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an emergent technique that reshapes the gut microbiome of the recipient in birds22. Several studies demonstrated that the intestinal microbiome is closely associated with duck growth performance1,3,4,7. Nevertheless, the available data regarding the effects of FMT on the cecal microbiota of ducks remain relatively limited. The intestinal microbiota is rapidly established and evolves continuously after hatching due to environmental exposure in poultry by approximately 42 days of age. The intestinal microbial community achieves a stable state characterized by increased structural diversity23. Further investigations were carried out to analyze the cecal microbiota of ducks in the FMT and CON groups to elucidate the beneficial effects of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). The diversity of gut microbiota is a reliable indicator of host health, and higher microbial diversity is generally associated with improved host health outcomes.24. Notably, in this study, the FMT group differed significantly in cecum alpha diversity from the CON group; FMT may have distinctly altered the microbial community diversity and abundance, as seen by the elevated Ace, Chao, and Shannon indices.

Also, it was reported that various Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla members contribute positively to host health and growth performance25,26. For example, an elevation in Firmicutes has been associated with enhanced nutrient absorption and increased body weight (BW) gain27,28. It is worth mentioning that the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is a crucial indicator of microbiota functionality, with a higher ratio favoring the reduction of pathogenic organisms29. Our findings showed that FMT raised the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which aligns with results from a previous study30. Given the observed increase in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio alongside improved average daily gain (ADG), we postulated that the alterations in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios induced by FMT treatment might contribute to the enhanced growth performance observed in ducks.

Several studies have indicated that FMT could modulate the gut microbiome of birds by reconstituting their intestinal microecology. This process alters host phenotypic traits by regulating nutrient metabolism and increasing feed intake and body weight, positively impacting bird growth performance.31,32. Differential analysis data from the taxonomic cladogram obtained by LEfSe revealed that FMT treatment increased the abundance of several beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Subdoligranulum, and Lactobacillus influviei, which contributes to the maintenance of the overall microbiota structure. These findings are partially consistent with the results reported in previous studies22,33. Subdoligranulum is known as a butyrate-producing bacterium34. Microbially derived butyrate has been revealed to improve intestinal epithelial barrier function in poultry35. Correspondingly, the Subdoligranulum benefits necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) by modulating the bacterial phage population and enhancing butyrate production, which is crucial for maintaining gut health and reducing inflammation36. In our study, the relative abundances of the Subdoligranulum were positively correlated with average daily gain (ADG).

In addition, SCFAs produced by gut microbiota play a vital role in enhancing ducks’ antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities37. Lactobacillus ingluviei, a novel strain of probiotic lactic acid bacteria, has demonstrated several beneficial effects on birds, such as anti-Salmonella activity and growth promotion38. Studies also revealed that L. ingluviei is associated with significant weight gain in ducks39. Recent studies have shown that a decrease in Lactobacillus abundance caused a reduction in bird growth performance because optimal levels of stable Lactobacillus indicate a balanced gut microbiome-mediated higher growth and vice versa40,41,42. Previous studies also reported that increased Lactobacillus abundance in the intestine significantly improves bird growth performance. Conversely, decreased Lactobacillus levels allow harmful bacteria to proliferate, negatively impacting growth performance43,44.

How the increased abundance of Lactobacillus in the cecum enhances duck growth performance is highly intriguing. Remarkably, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of newly hatched birds is almost entirely non-colonized by microorganisms, and a diverse range of bacteria begins to colonize it as the bird develops45. We hypothesized that increased Lactobacillus could be suppressed via multiple mechanisms, including competitive exclusion and pathogen antagonism. The pathogenesis and colonization of harmful bacteria begin when they bind to the host’s gut epithelium, triggering immune responses, disrupting the epithelial barrier, and enabling bacterial proliferation, leading to infection and inflammation46,47. However, owing to their competitive advantages over other bacteria, if Lactobacilli successfully colonized the duck gut, they could prevent the colonization of pathogenic bacteria by avoiding their binding to the adhesion sites of the gut epithelium46. In agreement with these reports, our study demonstrated a significantly higher abundance of Lactobacillus in the FMT group than in the CON group. Thus, combined with the improvement in body weight gain of ducks, we can further speculate that FMT treatment could stimulate intestinal development and improve cecum health in ducks by facilitating the relative abundance of Subdoligranulum, Lactobacillus, and L. ingluviei. Nonetheless, the specific Lactobacillus strains that play a crucial role in enhancing duck growth performance remain to be further investigated.

Currently, the role of Megamonas in animal health is unclear. Interestingly, a cluster dominated by Megamonas, resembling an enterotype-like structure, is significantly associated with human obesity48. Growing evidence suggests that Alistipes are often viewed as harmful bacteria, with their increased abundance closely associated with inflammatory responses49. In the present study, FMT reduced the abundance of Alistipes and decreased the overall abundance of the phylum Proteobacteria, which is known to contain potential pathogenic bacteria. It should be noted that Anaerobiospirillum, Mucispirillum, and Sutterella, which are negatively associated with duck growth performance, could be potential pathogens.

FMT showed an exciting prospect in improving the gut health of birds. Regrettably, our study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, identifying the composition of core microbiota in fecal suspensions through 16S rRNA or metagenomic sequencing techniques is crucial before FMT treatment. Secondly, conducting in vitro experiments simulating gastrointestinal digestion before FMT would be necessary, although in vitro experiments cannot ultimately reveal the complex interaction mechanism between the gastrointestinal microbiome and host in vivo50,51. Overall, these results indicated that the improved growth performance through FMT could be associated with reducing proinflammatory pathogen colonization in the duck cecum. This protective effect likely results from increased microbial diversity and enhanced cecal health.

Conclusions

Taken together, this study highlights the potential of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as an emerging technique to reshape the recipient cecal microbiome substantially in ducks. An early FMT could persistently improve duck growth performance by maintaining beneficial bacteria abundance at a higher level in the cecum, such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Subdoligranulum, which could contribute to maintaining cecal health. These findings contribute to an understanding that facilitating the bacterial diversity in the cecum by early microbiota transplantation is an effective way to improve duck growth performance. Future research should focus on optimizing FMT protocols for duck production by utilizing a more defined and precise microbiota consortium rather than relying on crude fecal microbes and exploring the long-term impacts on immune function and metabolism.

Data availability

Raw data have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject number PRJNA1210849 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1210849?reviewer = 5lkj28jecn65hcbsk758lqfe4k). All other data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Temporal variation in production performance, biochemical and oxidative stress markers, and gut microbiota in Pekin ducks during the late growth stage. Poult. Sci. 103, 103894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.103894 (2024).

Wu, D. et al. Effects of fecal microbiota transplantation and fecal Virome transplantation on LPS-induced intestinal injury in broilers. Poult. Sci. 103, 103316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.103316 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. Metagenomic insights into the relationship between intestinal flora and residual feed intake of meat ducks. Poult. Sci. 103, 103836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.103836 (2024).

Vasai, F. et al. Lactobacillus sakei modulates mule Duck microbiota in ileum and Ceca during overfeeding. Poult. Sci. 93, 916–925. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2013-03497 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Dietary fibers with different viscosity regulate lipid metabolism via Ampk pathway: Roles of gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid. Poult. Sci. 101, 101742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.101742 (2022).

Quinger, F. et al. Effects of carriers for oils in compound feeds on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and gut microbiota in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 103, 103803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.103803 (2024).

Zhu, C. et al. Analysis of microbial diversity and composition in small intestine during different development times in ducks. Poult. Sci. 99, 1096–1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2019.12.030 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Duck compound probiotics fermented diet alters the growth performance by shaping the gut morphology, microbiota and metabolism. Poult. Sci. 103, 103647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.103647 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Beneficial effects of duck-derived lactic acid bacteria on growth performance and meat quality through modulation of gut histomorphology and intestinal microflora in muscovy ducks. Poult. Sci. 103, 104195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.104195 (2024).

Pickard, J. M., Zeng, M. Y., Caruso, R. & Nunez, G. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol. Rev. 279, 70–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12567 (2017).

Khattab, A. A. A., Basuini, E., El-Ratel, M. F. M., Fouda, S. F. & I. T. & Dietary probiotics as a strategy for improving growth performance, intestinal efficacy, immunity, and antioxidant capacity of white Pekin ducks fed with different levels of CP. Poult. Sci. 100, 100898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.11.067 (2021).

Weingarden, A. R. & Vaughn, B. P. Intestinal microbiota, fecal microbiota transplantation, and inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 8, 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1290757 (2017).

Metzler-Zebeli, B. U. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant from highly feed efficient donors affects cecal physiology and microbiota in low- and high-feed efficient chickens. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01576 (2019).

Yan, C. et al. Exogenous fecal microbial transplantation alters fearfulness, intestinal morphology, and gut microbiota in broilers. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 706987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.706987 (2021).

Glendinning, L., Chintoan-Uta, C., Stevens, M. P. & Watson, M. Effect of cecal microbiota transplantation between different broiler breeds on the chick flora in the first week of life. Poult. Sci. 101, 101624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2021.101624 (2022).

Zhang, X. L. et al. Chicken jejunal microbiota improves growth performance by mitigating intestinal inflammation. Microbiome. 10, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01299-8 (2022).

Elokil, A. A. et al. Early life microbiota transplantation from highly feed-efficient broiler improved weight gain by reshaping the gut microbiota in laying chicken. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1022783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1022783 (2022).

Salim, H. M. et al. Supplementation of direct-fed microbials as an alternative to antibiotic on growth performance, immune response, cecal microbial population, and ileal morphology of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 92, 2084–2090. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2012-02947 (2013).

Rooks, M. G. & Garrett, W. S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.42 (2016).

Schuijt, T. J. et al. The intestinal microbiota and host immune interactions in the critically ill. Trends. Microbiol. 21, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.02.001 (2013).

Becattini, S., Taur, Y. & Pamer, E. G. Antibiotic-induced changes in the intestinal microbiota and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 458–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.003 (2016).

Liu, Q. et al. Early fecal microbiota transplantation continuously improves chicken growth performance by inhibiting age-related Lactobacillus decline in jejunum. Microbiome 13, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-024-02021-6 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Hen raising helps chicks establish gut microbiota in their early life and improve microbiota stability after H9N2 challenge. Microbiome 10, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01200-z (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of Bacillus subtilis and coccidial vaccination on cecal microbial diversity and composition of Eimeria-challenged male broilers. Poult. Sci. 98, 38393849. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez096 (2019).

Wexler, H. M. Bacteroides: The good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 593–621. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00008-07 (2007).

Wang, C. et al. Protective effects of different Bacteroides vulgatus strains against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute intestinal injury, and their underlying functional genes. J. Adv. Res. 36, 2737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2021.06.012 (2021).

Oakley, B. B. et al. The chicken gastrointestinal microbiome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 360, 100112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6968.12608 (2014).

Lee, K. C., Kil, D. Y. & Sul, W. J. Cecal microbiome divergence of broiler chickens by sex and body weight. J. Microbiol. 55, 939–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-017-7202-0 (2017).

Ge, C. et al. Plant essential oils improve growth performance by increasing antioxidative capacity, enhancing intestinal barrier function, and modulating gut microbiota in muscovy ducks. Poult. Sci. 102, 102813 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.102813 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Ameliorative effect of buckwheat polysaccharides on colitis via regulation of the gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 227, 872–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.12.155 (2023).

Fu, Y. et al. Effects of early-life cecal microbiota transplantation from divergently selected inbred chicken lines on growth, gut serotonin, and immune parameters in recipient chickens. Poult. Sci. 101, 101925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.101925 (2022).

Song, J. et al. Early fecal microbiota transplantation from high abdominal fat chickens affects recipient cecal Microbiome and metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1332230. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1332230 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Dietary supplementation of Bilberry anthocyanin on growth performance, intestinal mucosal barrier and cecal microbes of chickens challenged with Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 14, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00799-9 (2023).

Radjabzadeh, D. et al. Gut microbiome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Nat. Commun. 13, 7128. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34502-3 (2022).

Onrust, L. et al. Steering endogenous butyrate production in the intestinal tract of broilers as a tool to improve gut health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2, 75. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2015.00075 (2015).

Lin, H. et al. Multiomics study reveals Enterococcus and Subdoligranulum are beneficial to necrotizing Enterocolitis. Front. Microbiol. 12, 752102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.752102 (2021).

Fu, Y. et al. Pleurotus eryngii polysaccharides alleviate aflatoxin B1-induced liver inflammation in ducks involving in remodeling gut microbiota and regulating SCFAs transport via the gut-liver axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 271, 132371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132371 (2024).

Thomas, J. et al. (ed, V.) Effect of Turkey-derived beneficial Bacteria Lactobacillus salivarius and Lactobacillus ingluviei on a multidrug-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg strain in Turkey Poults. J. Food Prot. 82 435–440 https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-286 (2019).

Angelakis, E. & Didier, R. The increase of Lactobacillus species in the gut flora of newborn broiler chicks and ducks is associated with weight gain. PloS One. 5, e10463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010463 (2010).

Xi, Y. et al. Characteristics of the intestinal flora of specific pathogen free chickens with age. Microb. Pathog. 132, 32534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.05.014 (2019).

An, K. et al. Dietary Lactobacillus plantarum improves the growth performance and intestinal health of Pekin ducks. Poult. Sci. 101, 101844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.101844 (2022).

Abdel-Moneim, A. E., Elbaz, A. M., Khidr, R. E. & Badri, F. B. Effect of in Ovo inoculation of Bifidobacterium spp. On growth performance, thyroid activity, ileum histomorphometry, and microbial enumeration of broilers. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 12, 873882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-019-09613-x (2020).

Forte, C. et al. Dietary Lactobacillus acidophilus positively influences growth performance, gut morphology, and gut microbiology in rurally reared chickens. Poult. Sci. 97, 930936. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pex396 (2018).

Shokryazdan, P. et al. Effects of a Lactobacillus salivarius mixture on performance, intestinal health and serum lipids of broiler chickens. PloS One. 12, e0175959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175959 (2017).

Varmuzova, K. et al. Composition of gut microbiota influences resistance of newly hatched chickens to Salmonella Enteritidis infection. Front. Microbiol. 7, 957. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00957 (2016).

Huang, R. et al. Lactobacillus and intestinal diseases: Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Microbiol. Res. 260, 127019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2022.127019 (2022).

Zeise, K. D. et al. Interplay between Candida albicans and lactic acid Bacteria in the Gastrointestinal tract: Impact on colonization resistance, microbial carriage, opportunistic infection, and host immunity. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, e0032320. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00323-20 (2021).

Wu, C. et al. Obesity-enriched gut microbe degrades myo-inositol and promotes lipid absorption. Cell. Host Microbe. 32, 13011314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2024.06.012 (2024).

Cobo, F. et al. First description of abdominal infection due to Alistipes onderdonkii. Anaerobe 66, 102283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2020.102283 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Washed microbiota transplantation vs. manual fecal microbiota transplantation: Clinical findings, animal studies and in vitro screening. Protein Cell. 11, 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-019-00684-8 (2020).

Ma, Z. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves chicken growth performance by balancing jejunal Th17/Treg cells. Microbiome 11, 137. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-023-01569-z

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Guizhou University for offering the facilities and equipment essential for experimenting. We also extend our heartfelt gratitude to Professor S.L.Y for their invaluable guidance and support in preparing this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 31960682), the Chinese Government Grant for Supporting the Development of Local Science and Technology (No. (2019)4021), the Agricultural Major Special Project of Guizhou Province (No. (2019)5203), the Special Research Projects of Guizhou Province (No. (2020)1Y041), and the Guizhou University College Students SRT Plan Project (No. GD SRT 20), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y, B.L.Y, F.Y.L, and Z.Q.H made data curation; B.L.Y, F.Y.L, Z.Q.H, and P.S are involved in the Methodology; Y.Y and B.L.Y conducted the statistical analysis; Y.Y and P.S wrote the original draft preparation; Y.Y and S.L.Y wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Guizhou University (No. EAE-GZU-2020-E012). We confirm that all methods were performed under relevant guidelines and regulations. Additionally, we confirm that we have fully complied with the latest version of the ARRIVE guidelines in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yue, Y., Yao, B., Liao, F. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves Sansui duck growth performance by balancing the cecal microbiome. Sci Rep 15, 22403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04942-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04942-0