Abstract

Emergency medical service (EMS) plays a vital role in the healthcare system by delivering rapid response and acute care in critical situations. However, limited information exists regarding the prevalence and associated factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorder (WMSD) symptoms amongst EMS workers. This study aimed to examine the prevalence of WMSD symptoms and identify associated risk factors through a cross-sectional survey conducted in Hong Kong. A total of 404 EMS workers participated in the study. The overall prevalence of self-reported WMSD symptoms was 38.4%. Gender, exercise habits and years of work experience were significant predictors. In addition, several work-related tasks, such as standing, walking, sitting, balancing, twisting the body, gripping with fingers, lifting, pushing, hand control, wrist twisting and prolonged fixed hand movements, were positively associated with WMSD symptoms. These findings provided a strong foundation for developing targeted interventions to reduce WMSD risks and improve the health and well-being of EMS workers. The study also offered practical recommendations to help lower the prevalence of WMSDs in this essential workforce.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emergency medical service (EMS) constitutes a critical component of the healthcare system, providing rapid medical response and acute care in situations where time and expertise are paramount1. The primary function of EMS is to deliver urgent medical attention in pre-hospital settings, stabilise patients and prepare them for or prevent the need for hospital admission. EMS personnel occupy a pivotal role within EMS, tasked with providing critical care under conditions that are often highly stressful and physically demanding2. The nature of their work, which frequently involves the urgent transport and handling of patients, exposes them to a unique set of occupational hazards3. These occupational hazards include repetitive lifting and manoeuvring of patients and quick adaptation to varied and unpredictable physical environments. Such occupational hazards inherently increase the risk of developing WMSDs, encompassing a range of conditions from chronic back pain to acute joint and muscle injuries4.

WMSDs are a pervasive and important category of occupational health issues that affect the musculoskeletal system, including muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves and bones, primarily resulting from or exacerbated by workplace activities5. WMSDs manifest as a spectrum of symptoms ranging from mild discomfort and fatigue to severe pain and disability, impacting various body parts such as the back, neck, shoulders and upper and lower extremities6. The aetiology of WMSDs is multifactorial, involving repetitive motion, overexertion, poor ergonomics, sustained awkward postures and prolonged static positions6. Moreover, WMSDs affect the health and well-being of workers, leading to decreased productivity and increased absenteeism7. WMSDs also impose remarkable economic burdens on healthcare systems and businesses due to increased workers’ compensation claims and medical expenses8. Consequently, understanding the WMSDs is crucial for promoting a healthy workforce and optimising organisational performance.

Previous research has extensively examined the prevalence and factors associated with WMSDs across diverse sectors. Notably, Lee, et al.4 executed a comprehensive cross-sectional study to assess the prevalence and risk factors contributing to WMSDs amongst construction workers, highlighting specific occupational hazards such as heavy lifting and frequent bending. Similarly, Yang, et al.9 explored these disorders within the manufacturing sector, focusing on repetitive assembly tasks and prolonged standing, which significantly contribute to the development of WMSDs. In the healthcare domain, studies such as those by Karki, et al.10 and Nazzal, et al.11 have shed light on the high incidence of WMSDs amongst healthcare professionals, primarily driven by the demands of patient handling and long working hours. Despite these insights, there remains a notable research gap in the literature concerning EMS personnel, a group particularly vulnerable due to their work’s dynamic and physically intensive nature. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and associated risk factors of WMSDs amongst EMS personnel. This study addresses this research gap by conducting a detailed cross-sectional analysis of the prevalence and associated risk factors of WMSDs amongst EMS personnel. By filling this research gap, the study enriches the existing body of knowledge and lays the groundwork for developing targeted interventions to mitigate these risks, ultimately enhancing occupational health standards and worker well-being in this critical sector.

Methodology

Study design and participants

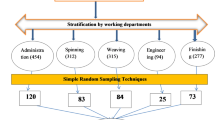

The research study has gained the ethics approval from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Ethics Committee (Ethics Approval Number: HSEARS20220606001). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This research was designed as a cross-sectional survey targeting EMS personnel in Hong Kong to investigate the prevalence and contributing factors of WMSDs. The cohort of participants was sourced from the HKFSD, focusing on individuals with more than one year of occupational experience in this demanding field. Exclusion criteria were applied to potential participants who had pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions or had suffered recent accidents that could skew the results, ensuring a focus on WMSDs directly attributable to their work conditions. Participants were clearly informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. All participant responses were kept strictly confidential by assigning unique identifiers to anonymise data and securely storing all collected information on password-protected systems accessible only by authorised research personnel. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants, further endorsed by approval from the institutional ethics committee. The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula proposed by Daniel and Cross12which was based on an anticipated 65% prevalence rate of WMSD symptoms amongst healthcare workers as identified in recent literature13. Factoring in a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence interval and accounting for a potential 10% non-response rate, the study aimed to include 385 participants selected via random sampling methodology.

Questionnaire design

The study employed a face-to-face questionnaire survey as its primary data collection method. A structured self-reported questionnaires were developed through collaboration between a panel of three ergonomic experts and two ambulance professionals with over ten years of work experience in EAS. This questionnaire comprised three main sections: the initial section gathered demographic data such as gender, age, body mass index (BMI), exercise habits and years of work experience. The second section focused on work-related factors, encompassing standing, walking, sitting, bending, balancing, twisting the body sideways, hands reaching forward, hands capturing, fingers gripping, lifting, carrying, pushing, pulling, hands controlling, twisting the wrist, hands repetitive motions, long-term fixed hand motions and operating vibrating machines. These factors were informed by established research findings11,14. The third component utilised the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ), which underwent rigorous translation into Chinese following established protocols4. NMQ is designed to assess WMSD symptoms across various body regions (neck, shoulders, upper back, elbows, lower back, wrists/hands, hips/thighs, knees and ankles/feet) experienced within the past year. NMQ’s reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.77 to 0.98 and validity from 0.80 to 0.99, has been validated in previous studies15. Moreover, adaptations of the NMQ across different cultural contexts, including China, have consistently demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties4,9ensuring robustness and reliability in capturing WMSD data amongst EMS personnel in this study. The main outcome measure was the total number of WMSD symptoms across various body regions (neck, shoulders, upper back, elbows, lower back, wrists/hands, hips/thighs, knees and ankles/feet) experienced within the past year.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analysed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) statistics software, version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Initially, descriptive statistics were applied to ascertain the distribution of individual and occupational characteristics of the respondents. The prevalence rates of WMSD symptoms were quantitatively expressed as percentages. Examining how demographic and work-related factors predict WMSD symptoms involved hierarchical linear regression, with a significance threshold set at 5%. Hierarchical linear regression is a statistical method used to understand how different sets of factors (or variables) contribute to explaining an outcome. Researchers enter these sets of variables into the model step by step, in a specific order, to see how much each group adds to the prediction. The hierarchical linear regression was chosen because it has been widely used in research on WMSD symptoms16,17. The hierarchical linear regression facilitates the examination of predictors in sequential order, enabling the testing of their predictability while controlling for the influence of various sets of independent variables on the dependent variables. This approach systematically assesses the contribution of each predictor, adjusting for potential confounding factors, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the results in determining the impact of specific variables on outcomes of interest. Specifically, the statistical method could help understand the influence of various predictors on the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel, accounting for the hierarchical data structure that might include multiple levels, such as demographic variables nested within work-related factors. This approach aligned with the research objective of understanding the additive effects of these predictors. While alternative methods, such as logistic regression, are suitable for binary outcomes, the continuous outcome variable of this study was the total number of WMSD symptoms across various body regions (neck, shoulders, upper back, elbows, lower back, wrists/hands, hips/thighs, knees and ankles/feet) experienced within the past year, necessitating linear regression techniques. Structural equation modelling, although powerful for assessing complex relationships and latent constructs, was not employed due to this study’s focus on observed variables and the absence of intricate path structures. This research aimed to assess the extent to which work-related factors contribute to the variance in the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel while accounting for demographic influences. In the initial phase of the analysis (Model 1), demographic variables such as gender, age, BMI, exercise habits and years of work experience were incorporated. Subsequently, work-related factors, including standing, walking, sitting, bending, balancing, twisting the body sideways and wrist, hands reaching forward, hands capturing, hands controlling, fingers gripping, lifting, carrying, pushing, pulling, long-term fixed hand motions, hands repetitive motions and operating vibrating machines, were integrated into the second phase (Model 2). At each phase, the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by these predictors, denoted as R2was evaluated. Additionally, the change in R2indicating the increase in explanatory power resulting from adding work-related factors beyond the demographic variables, was calculated. The hierarchical linear regression model is particularly useful in occupational health research because it enables the inclusion of individual-level variables (e.g. age, gender and years of work experience) and group-level variables (e.g. job demands) in a single analysis. Tolerance values and the variance inflation factor (VIF) were calculated to evaluate multicollinearity amongst the independent variables. VIF is a measure used to check whether the variables in a model are too closely related to each other. When two or more variables are highly related (a situation called multicollinearity), it can distort the results of the analysis. VIF gives a number that indicates how much the results are being affected. A low VIF means there is little overlap between variables, which is acceptable. A high VIF means some variables may be redundant, and the model could be less reliable. A comprehensive codebook was provided to outline the structure, variables and coding schemes used in the study. This codebook was included as supplementary material to assist in understanding the data collection and analysis processes.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

A total of 404 EMS personnel were surveyed. The age of the respondents ranged from 20 years to 43 years (mean = 26.2 years, SD = 3.7 years). The participants included 390 males and 14 females. The respondents’ BMI ranged from 18.25 to 31.67. The majority (98%, n = 396) of the respondents had at least one time exercise weekly. Moreover, 56.2% (n = 227) of the participants had less than five years of work experience.

Work-related factors

Table 1 comprehensively summarises work-related factors for EMS personnel, detailing the frequency and percentage distribution of various physical demands at their daily work. For standing, the majority of EMS personnel (62.4%) reported standing ‘always’, with 30% reporting ‘non-stop’ standing. Walking was an even more common task, with 73% ‘always’ walking and 17.3% walking ‘non-stop’. Sitting was mostly done ‘sometimes’ (72.8%), and only 7.4% of workers sit ‘non-stop’. Bending occurred frequently, with 67.8% doing so ‘sometimes’ and 23.5% ‘always,’ but none reported ‘non-stop’ bending. Balancing and twisting the body sideways were often required, with nearly half of respondents reporting they ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ balanced or twisted, while a small percentage performed these tasks non-stop. Tasks involving hand movements, such as reaching forward, capturing objects and fingers gripping, were regularly performed by EMS personnel, with nearly half reporting that they performed these actions ‘always’. Lifting, carrying, pushing and pulling were common tasks as well, typically done ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’. However, ‘non-stop’ engagement in these tasks remained minimal. Hands controlling were common tasks, with over 95% reporting that they performed these actions ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’. Wrist twisting, repetitive hand movements and long-term fixed hand motions frequently occurred, with over half of the workers reporting these activities occurred ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’. Operating vibrating machines was less common, with only 7.4% doing so ‘always’ and none ‘non-stop,’ indicating that this task was less integral to daily ambulance work than the other tasks.

Prevalence of WMSD symptoms

Table 2 provides a detailed summary of the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel, focusing on different body parts. Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of WMSD symptoms by body part amongst EMS personnel. It visually highlights the most affected regions, with the shoulder, lower back and ankles/feet showing the highest prevalence rates. The data showed that 40.6% of workers reported neck-related symptoms, whereas 52.2% experienced shoulder discomfort. Upper back symptoms were less prevalent, with only 29.5% affected, whereas 49.3% reported lower back issues. Elbow and wrist/hand symptoms were reported by 25.7% and 30.9% of workers, respectively. Lower body symptoms were also remarkable, with 35.4% reporting issues in the hips/thighs, 34.4% in the knees and 47.8% in the ankles/feet. In this study, the overall prevalence of self-reported WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel was 38.4%. The prevalence of WMSDs in these body parts highlights the physically demanding nature of ambulance work, with notable impacts across upper and lower body regions.

Prediction of WMSD symptoms

All independent variables demonstrated tolerance values exceeding 0.1 and VIFs below 10 (Table 3), suggesting that multicollinearity did not pose a significant concern in this analysis, in accordance with the criteria set by Hair, et al.18. The multicollinearity assessment showed the VIF values were within the recommended range, thus enhancing the credibility of the results. The results of the hierarchical regression are presented in Table 3. Model 1 shows that gender and exercise habits were significantly negatively associated with the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel. However, years of work experience were significantly positively associated with the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel. The demographic variables explained 12.7% of the variance in the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel (p < 0.001).

When demographic variables were controlled, the integration of the work-related factors increased the explanatory power of the regression model by 20.7%. Specifically, standing, walking, sitting, balancing, twisting the body sideways, fingers gripping, lifting, pushing, hands controlling, twisting the wrist and long-term fixed hand motions positively predicted the WMSD symptoms of EMS personnel. Standing and sitting involve diverse postural variations that can differentially impact workers’ WMSD19. In this study, standing and sitting were considered to comprehensively assess how they influence the WMSD of EMS workers. This consideration allows for targeted interventions to alleviate WMSD symptoms amongst EMS workers. According to Cohen’s benchmarks20 an f2 value of 0.311 is considered a large effect size, indicating that adding work-related factors substantially improves the model’s explanatory power regarding the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel.

Discussion

This study investigated the presence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel in Hong Kong and identified potential risk factors associated with WMSDs. This study mainly found that the overall prevalence of self-reported WMSD symptoms amongst EMS workers was 38.4%. The significant predictors of WMSD prevalence amongst EMS workers included gender, exercise habits and years of work experience. Additionally, specific occupational activities, such as standing, walking, sitting, balancing, body twisting, finger gripping, lifting, pushing, hand controlling, wrist twisting and prolonged fixed hand actions, were positively associated with WMSD symptoms amongst EMS workers. Theoretical contributions and practical implications are discussed below.

Theoretical contributions

The prevalence of WMSDs amongst EMS workers varies globally. For instance, the prevalence rates of EMS workers ranging from 52 to 71% were reported in Jordan11. The overall prevalence of self-reported WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel was 38.4% in this study, which was lower than that (57.9%) amongst construction workers4. The discrepancy in these findings invites an in-depth examination of the occupational risks and ergonomic challenges faced by these two distinct worker groups. EMS personnel are frequently exposed to high-stress situations that require rapid physical responses, often in constrained environments21. The nature of their work demands repetitive movements, heavy lifting and extended periods of riding in vehicles, all of which are risk factors for developing WMSDs. Conversely, construction workers, while engaged in physically demanding tasks, encounter different types of ergonomic challenges, such as sustained heavy lifting, use of heavy machinery and work in various postures that may be more continuously strenuous than those typically experienced by EMS personnel22,23. The high prevalence of WMSDs in the construction sector could be attributed to these factors, coupled with potentially long exposure times to risk conditions per workday. The variance between the two groups might also be influenced by differences in workplace safety regulations, training on proper lifting techniques and the use of ergonomic aids and protective equipment24,25. Moreover, the low prevalence of WMSDs amongst EMS personnel, despite the demanding nature of their job, could reflect variances in health reporting behaviour26access to medical care27 or preventive measures such as regular training in manual handling techniques and the provision of ergonomically designed equipment28.

This study found that male EMS personnel exhibited a higher prevalence of WMSD symptoms compared with their female counterparts. This result prompted a close examination of gender-specific occupational exposure and ergonomic risk factors in this field. Gender-specific risks in WMSDs arise from a combination of biological, ergonomic and psychosocial factors that differentially affect men and women in occupational settings. Women often report higher prevalence rates of WMSDs than men, which may be attributed to physiological differences such as lower muscle mass29 and joint laxity30. In physically demanding professions such as EMS, standardised tools and workspaces are typically designed for average male anthropometrics, potentially placing female workers at a biomechanical disadvantage31. Moreover, gender-specific roles and expectations may lead to differing exposures to physical and psychosocial stressors32. Typically, ambulance work involves strenuous physical activities such as lifting and transporting patients, which might traditionally be allocated more frequently to males than to females, possibly due to perceptions of strength. The perceptions of strength could expose male workers to a greater risk of musculoskeletal strain and injury than female workers. Furthermore, differences in muscle mass and body mechanics between genders could mean that similar tasks impose different strain levels on male and female bodies, potentially exacerbating the risk for males under certain conditions33. Additionally, there could be variations in job assignments, with males possibly engaging more frequently in roles that involve higher physical exertion or riskier tasks than females, contributing to the observed disparity in WMSD prevalence. Overall, understanding and addressing the nuances of how gender impacts the prevalence of WMSD symptoms in EMS personnel are crucial for developing effective occupational health policies and interventions that enhance the safety and well-being of all employees in this challenging field.

The findings from the study revealed a significant negative association between exercise habits and the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel. This finding suggested that regular physical activity may play a protective role in mitigating the risk of developing WMSDs in this physically demanding occupation. Regular exercise could potentially enhance muscle strength, flexibility and endurance, which are critical in reducing the vulnerability to injuries associated with repetitive movements and physically strenuous activities typical in ambulance work34. Exercise might have several benefits that directly impact the musculoskeletal health of EMS personnel. Firstly, it improves muscle conditioning, enhancing the body’s ability to withstand lifting and moving patients and equipment35. Secondly, regular physical activity helps maintain joint mobility and reduces the risk of stiffness, thereby lowering the chances of injury during physically demanding tasks36. Furthermore, exercise improves overall physical fitness, leading to good body mechanics, enhanced posture and efficient movement patterns during work activities, reducing the overall strain on the musculoskeletal system37. The significant negative association between exercise habits and WMSD symptoms highlights the critical role of physical fitness in occupational health, particularly for those in high-risk jobs like ambulance services. This finding advocates for a strategic focus on promoting regular exercise as a fundamental component of workplace health initiatives, aiming to safeguard the musculoskeletal health of EMS personnel through preventative measures that are feasible and beneficial.

The analysis from the study revealed a significant positive association between years of work experience and the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel, consistent with the findings of a previous study38. This finding indicated that the likelihood of experiencing WMSD symptoms increases with the duration of service in the ambulance sector. This association is particularly pertinent in occupational health discussions because it underscores the cumulative impact of prolonged exposure to the physical demands and stressors inherent in emergency medical services. The nature of ambulance work often involves repetitive tasks, heavy lifting and urgent, physically strenuous activities, such as carrying patients and equipment, which can impose significant biomechanical stress on the body39. Over time, these repeated stress exposures can lead to wear and tear of muscles, joints and ligaments, thereby increasing the risk of chronic musculoskeletal injuries or disorders. The association between increased work experience and high WMSD symptom prevalence suggests that seasoned EMS personnel might be accumulating physical wear over their years of service but may also be less likely to adjust their work habits to mitigate this risk, possibly due to ingrained practices or a diminished adaptability to new ergonomic techniques.

The study’s findings indicated that several work-related factors, such as standing, sitting, balancing, twisting the body sideways, fingers gripping, lifting, pushing, controlling with hands, twisting the wrist and maintaining long-term fixed hand motions, were positively associated with the prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel. These activities, typically requiring sustained postures or repetitive movements, contribute to physical strain and stress on the musculoskeletal system. For instance, standing or sitting for prolonged periods can lead to lower back pain40whereas lifting and pushing can exacerbate wear and tear on the joints and soft tissues41. The twisting and controlling movements involving the wrist and fingers may similarly impose significant strain on these areas, increasing the risk for WMSD symptoms such as tendonitis or carpal tunnel syndrome. These findings underscored the complexity of task-related risk factors in predicting WMSDs amongst EMS personnel.

Practical implications

On the basis of the findings of this study, several practical recommendations were made to reduce the prevalence of WMSDs amongst EMS personnel. Firstly, the higher prevalence of WMSDs amongst male EMS personnel than amongst female EMS personnel underlines the necessity for targeted ergonomic interventions that consider these gender-specific risks and exposures. Adjustments to training programmes that emphasise proper lifting techniques and the use of assistive devices can be crucial in mitigating these risks. Implementing team lifting protocols or enhancing mechanical aids could reduce physical load, particularly in situations that traditionally rely on physical strength. Regular ergonomic assessments could also help identify and modify task-specific risks associated with WMSD symptoms amongst male EMS personnel. Moreover, this finding suggested that occupational health strategies should focus on generic interventions and consider tailored approaches that address the specific needs and risks associated with different worker groups within the same professional context. Furthermore, the importance of fostering a workplace culture that encourages all employees should be highlighted, regardless of gender, to report symptoms and injuries without stigma or fear of repercussion, ensuring early detection and management of WMSDs.

Secondly, the preventive role of exercise in relation to WMSDs underscores the importance of integrating regular physical fitness programmes into the occupational health strategies for EMS personnel. Such programmes could include targeted strength training, flexibility routines and aerobic conditioning tailored to address the specific physical demands faced by these professionals. By enhancing physical resilience, these exercise programmes could significantly reduce the incidence of WMSDs, leading to improved worker health, enhanced job performance and reduced absenteeism due to injury. Moreover, establishing a workplace culture that promotes and facilitates regular exercise could be beneficial, achieved through on-site fitness facilities, scheduled workout sessions during shifts or partnerships with local gyms and fitness centres offering discounted memberships for EMS personnel. Encouraging a proactive approach to physical fitness could also be supplemented with educational programmes that inform workers about the benefits of exercise in preventing musculoskeletal injuries and provide practical advice on how to incorporate physical activity into their daily routines.

Thirdly, it would be beneficial to introduce or enhance the use of assistive devices that reduce physical strain, such as powered stretchers or load-assistance devices (e.g. PBEs) for ambulance loading. These devices alleviate physical strain and enhance the efficiency and safety of ambulance operations. By integrating these advanced ergonomic tools, EMS can protect their workforce from the long-term health issues often seen in high-risk jobs, ultimately leading to improved worker satisfaction, reduced absenteeism due to injury and a sustainable working environment for EMS personnel.

Last, gender considerations should be made in risk assessment and ergonomic intervention planning. Designing equipment and tasks that account for a wider range of body types and physical capacities of male and female EMS workers is essential to promoting musculoskeletal health across the EMS workforce.

Limitations

This study had three limitations. First, potential confounding variables such as stress and lack of sleep in relation to WMSD symptoms were not considered. Research indicated that stress can exacerbate musculoskeletal discomfort amongst workers, suggesting a significant association between stress and WMSDs42. Similarly, sleep disturbances have been linked to increased musculoskeletal pain, highlighting the need to address sleep quality43. Second, the use of self-reported data in assessing the prevalence of WMSD symptoms presented the potential for recall bias and underreporting. Participants may unintentionally misremember or understate their symptoms due to factors such as stigma, fear of repercussions or simply forgetting past instances of discomfort or injury. This recall bias and underreporting could lead to an incomplete or skewed representation of the actual prevalence of WMSDs. Third, the cross-sectional design of this study limited the ability to establish causal relationships because the design captures data at a single time. This limitation prevents the study from definitively determining whether identified risk factors directly cause WMSDs or are merely associated with them. Last, the sample size of 14 female EMS workers was small, limiting the investigation of how work tasks may differentially affect WMSD symptoms across genders. Therefore, future research should recruit a balanced representation of male and female EMS workers to robustly investigate potential gender-specific interactions in WMSD risk factors.

Conclusion

This study investigated the prevalence of WMSD symptoms and associated work-related factors amongst EMS personnel in Hong Kong. The NMQ was utilised to assess the prevalence of WMSD symptoms and hierarchical linear regression was employed to analyse demographic and work-related predictors that affect this prevalence. Findings revealed that the average prevalence of WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel over the past year stood at 38.4%. A breakdown of these symptoms showed that 40.6% of workers reported neck-related issues, 52.2% experienced shoulder discomfort and 49.3% had lower back problems, whereas only 29.5% reported upper back symptoms. Additionally, 25.7% of the workers suffered from elbow symptoms, and 30.9% reported wrist/hand issues. Concerning lower body ailments, 35.4% experienced symptoms in the hips/thighs, 34.4% in the knees and 47.8% in the ankles/feet. The variance in WMSD symptom prevalence could be attributed to the demographic and work-related characteristics of EMS personnel. The study also identified significant associations, with gender and exercise habits showing a negative association and years of work experience displaying a positive association with the prevalence of WMSD symptoms. Moreover, work-related activities such as standing, walking, sitting, balancing, body twisting, fingers gripping, lifting, pushing, hand controlling, wrist twisting and maintaining long-term fixed hand motions were positively linked to the onset of WMSD symptoms. These insights provided a theoretical foundation for developing effective interventions to reduce WMSD symptoms amongst EMS personnel, ultimately enhancing their health and well-being.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Balasundaram, A. et al. Internet of things (IoT)-based smart healthcare system for efficient diagnostics of health parameters of patients in emergency care. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 18563–18570 (2023).

Glawing, C., Karlsson, I., Kylin, C. & Nilsson, J. Work-related stress, stress reactions and coping strategies in ambulance nurses: a qualitative interview study. J. Adv. Nurs. 80, 538–549 (2024).

Powell, J. R. et al. National examination of occupational hazards in emergency medical services. Occup. Environ. Med. 80, 644–649 (2023).

Lee, Y. C., Hong, X. & Man, S. S. Prevalence and associated factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders symptoms among construction workers: a cross-sectional study in South China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 4653 (2023).

Greggi, C. et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 13, 3964 (2024).

Besharati, A., Daneshmandi, H., Zareh, K., Fakherpour, A. & Zoaktafi, M. Work-related musculoskeletal problems and associated factors among office workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 26, 632–638 (2020).

Singh, P., Bhardwaj, P., Sharma, S. K. & Agrawal, A. K. Association of organisational factors with work-related musculoskeletal disorders and psychological well-being: a job demand control model study. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 24, 593–606 (2023).

Bevan, S. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 29, 356–373 (2015).

Yang, F. et al. The prevalence and risk factors of work related musculoskeletal disorders among electronics manufacturing workers: a cross-sectional analytical study in China. BMC Public Health. 23, 10 (2023).

Karki, P. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with occupational musculoskeletal disorders among the nurses of a tertiary care center of Nepal. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health. 13, 375–385 (2023).

Nazzal, M. S. et al. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors affecting emergency medical services professionals in jordan: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 14, e078601 (2024).

Daniel, W. W. & Cross, C. L. Biostatistics: a Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences (Wiley, 2018).

Jacquier-Bret, J. & Gorce, P. Prevalence of body area work-related musculoskeletal disorders among healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 841 (2023).

Bryndal, A., Glowinski, S., Hebel, K., Grochulska, J. & Grochulska, A. The prevalence of neck and back pain among paramedics in Poland. J. Clin. Med. 12, 7060 (2023).

Deakin, J., Stevenson, J., Vail, G. & Nelson, J. The use of the nordic questionnaire in an industrial setting: a case study. Appl. Ergon. 25, 182–185 (1994).

Sezer, B., Kartal, S., Sıddıkoğlu, D. & Kargül, B. Association between work-related musculoskeletal symptoms and quality of life among dental students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23, 1–9 (2022).

Jeong, S. & Lee, B. H. The moderating effect of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in relation to occupational stress and health-related quality of life of construction workers: a cross-sectional research. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 147 (2024).

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J. & Black, W. C. Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Vol. 7 (Pearson Upper Saddle River, 2010).

Argus, M. & Paasuke, M. Musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among office workers in an activity-based work environment. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 28, 2419–2425 (2022).

Selya, A. S., Rose, J. S., Dierker, L. C., Hedeker, D. & Mermelstein, R. J. A practical guide to calculating cohen’sf 2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Front. Psychol. 3, 111 (2012).

Reuter, E. & Camba, J. D. Understanding emergency workers’ behavior and perspectives on design and safety in the workplace. Appl. Ergon. 59, 73–83 (2017).

Man, S. S., Chan, A. H. S. & Wong, H. M. Risk-taking behaviors of Hong Kong construction workers—a thematic study. Saf. Sci. 98, 25–36 (2017).

Wong, T. K. M., Man, S. S. & Chan, A. H. S. Exploring the acceptance of PPE by construction workers: an extension of the technology acceptance model with safety management practices and safety consciousness. Saf. Sci. 139, 105239 (2021).

Wong, T. K. M., Man, S. S. & Chan, A. H. S. Critical factors for the use or non-use of personal protective equipment amongst construction workers. Saf. Sci. 126, 104663 (2020).

Man, S. S., Chan, A. H. S., Alabdulkarim, S. & Zhang, T. The effects of personal and organizational factors on the risk-taking behavior of Hong Kong construction workers. Saf. Sci. 163, 105155 (2021).

Hutchinson, L. C., Forshaw, M. J. & Poole, H. Health behaviours in ambulance workers. J. Paramed. Pract. 12, 367–375 (2020).

Lawn, S. et al. The effects of emergency medical service work on the psychological, physical, and social well-being of ambulance personnel: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Psychiatry. 20, 1–16 (2020).

Man, S. S. et al. Effects of passive exoskeleton on trunk and gluteal muscle activity, spinal and hip kinematics and perceived exertion for physiotherapists in a simulated chair transfer task: a feasibility study. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 90, 103323 (2022).

Silva, O. F. et al. Do men and women have different musculoskeletal symptoms at the same musculoskeletal discomfort level? Ergonomics 65, 1486–1508 (2022).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among physical therapists in Taiwan. Medicine 101, e28885 (2022).

Castellucci, H. et al. Applied anthropometry for common industrial settings design: working and ideal manual handling heights. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 78, 102963 (2020).

Kelmendi, K. & Jemini-Gashi, L. An exploratory study of gender role stress and psychological distress of women in Kosovo. Women’s Health. 18, 17455057221097823 (2022).

Garcia, S. A., Vakula, M. N., Holmes, S. C. & Pamukoff, D. N. The influence of body mass index and sex on frontal and sagittal plane knee mechanics during walking in young adults. Gait Posture. 83, 217–222 (2021).

Yuniana, R. et al. The effectiveness of the weight training method and rest interval on VO2 max, flexibility, muscle strength, muscular endurance, and fat percentage in students. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 11, 213–223 (2023).

Harris, M. P. et al. Myokine musclin is critical for exercise-induced cardiac conditioning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6525 (2023).

Zhu, G. C., Chen, K. M. & Belcastro, F. Comparing different stretching exercises on pain, stiffness, and physical function disability in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 105, 953–962 (2024).

Fikri, F., Rekawati, E. & Permatasari, H. Exercise therapy is efficacious in reducing pain of musculoskeletal disorders in cleaning workers: a systematic review. Indones. J. Glob. Health Res. 6, 1557–1568 (2024).

Le, T. T. T., Jalayondeja, W., Mekhora, K., Bhuuanantanondh, P. & Jalayondeja, C. Prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among physical therapists in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 24, 6 (2024).

Gentzler, M. & Stader, S. Posture stress on firefighters and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) associated with repetitive reaching, bending, lifting, and pulling tasks. Work 37, 227–239 (2010).

Tahir, M. et al. Association of knee pain in long standing and sitting among university teachers: association of knee pain in university teachers. Healer J. Physiother. Rehabili. Sci. 3, 314–321 (2023).

Orr, R. et al. The impact of footwear on occupational task performance and musculoskeletal injury risk: a scoping review to inform tactical footwear. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19, 10703 (2022).

Cao, W. et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among hospital midwives in chenzhou, Hunan province, China and associations with job stress and working conditions. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy 14, 3675–3686 (2021).

Darvishi, E., Osmani, H., Aghaei, A. & Moloud, E. A. Hidden risk factors and the mediating role of sleep in work-related musculoskeletal discomforts. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 256 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72301110), the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (grant number 2024A04J2279), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number QNMS202418) and the Internal Research Fund, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (P0045874). Recruitment support from the Fire Sevices Department is highly appreciated by the authors as well.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Billy Chun Lung So: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Eva Wing Fong Lee: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Shamay Ng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing. Siu Shing Man: Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

So, B.C.L., Lee, E.W.F., Ng, S. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorder symptoms amongst emergency medical service workers. Sci Rep 15, 19806 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04945-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04945-x