Abstract

The proportion of elderly people infected with tuberculosis (TB) is increasing, and misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis are common. This study aimed to explore the diagnostic value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) for pulmonary TB (PTB) and to investigate age-related differences in lung microbial composition, clinical characteristics and imaging findings among PTB patients. We retrospectively recruited 162 suspected PTB patients, and finally 143 patients were used in this analysis. Patients were classified into two groups: adult (18 ≤ age < 60, n = 66) and elderly (Age ≥ 60, n = 77). Differences and associations in clinical characteristics, imaging findings, and lung microbiota were analyzed. Compared to adult patients, elderly patients had a higher prevalence of hypertension (31.17% vs. 9.09%, P = 0.0012), fever (20.78% vs. 4.55%, P = 0.0044) and chest tightness (24.68% vs. 10.61%, P = 0.0297), but a lower prevalence of chest pain (7.58% vs. 0%, P = 0.0139). For TB identification, mNGS had the highest positive rate (100%), followed by T-spot (74.75%), GeneXpert (37.80%) and acid-fast staining (AFS) (7.30%), and all the conventional methods showed slight higher positive rates in the elderly group compared to the adult group (P > 0.05). Bilateral lung infection was more common in elderly patients (79.22% vs. 60.61%, P = 0.0148), with infiltration (32.17%, 46/143), shadows (26.57%, 38/143), nodules (20.28%, 29/143), and bronchiectasis (20.28%, 29/143) being the most common imaging features. The diversity of the lung microbial communities was significantly lower in elderly patients compared to adults (P < 0.05). Clinical characteristics, imaging findings, and the top 20 most abundant species in lung microbiota showed significantly positive correlation. This study demonstrates that mNGS has excellent diagnostic value for PTB in both adult and elderly patients. Significant differences in clinical characteristics, imaging, and lung microbial composition were observed between the two groups. Understanding these differences may aid in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in elderly patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), which can affect all human organs except teeth, hair, and nails with the lungs being the primarily site of infection1. Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) represents the predominant manifestation of this disease. China is among the 30 countries with a high TB burden globally, facing significant challenges from drug-resistant TB and HIV co-infection. According to the WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2023, an estimated 748,000 new TB cases were reported in China in 2022, accounting for 7.1% of the global total (10 million). Although this marks a decrease from 780,000 in 2021 and 842,000 in 2020, China remains the third-highest country in terms of TB buren after India and Indonesia2.

While age-related disparities exist in tuberculosis distribution, elderly individuals along with young people and children constitute key demographics for prevention and control efforts. Elderly individuals are at heightened risk for TB due to diminished immune function and comorbidities such as diabetes3. As China’s population ages, the incidence rate of tuberculosis among older adults continues to rise annually. Moreover, misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis rates remain alarmingly high due to atypical clinical presentations, posing substantial threats to the health and well-being of older individuals. Therefore, early detection, prompt diagnosis and proactive treatment are critical for preventing and managing pulmonary tuberculosis in this demographic.

In recent years, the interplay between lung microbiota and pulmonary diseases has emerged as a significant area of research. Investigating the lung microbiome offers novel insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying lung disorders. Alterations in microbial composition and abundance within the lungs may precede clinical manifestations of disease, presenting opportunities for early diagnosis and intervention4. The advent of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) technology has established its pivotal role in diagnosing and managing infectious diseases5,6,7. Furthermore, the ability to detect microbiota enhances the broader applicability of mNGS across various medical contexts8,9. In this study, we aims to investigate age-related differences in pulmonary microbial composition among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) mNGS, as well as to elucidate the relationship between microbial profiles and both clinical and imaging characteristics.

Materials and methods

Study patients

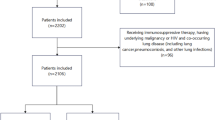

Totally 162 patients admitted to the department of infectious diseases at Quzhou People’s Hospital from June 2021 to February 2023 were retrospectively recruited. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis; (2) performed bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) mNGS with TB detected; (3) age ≥ 18 years; and (4) complete clinical profiles. For patients who underwent multiple mNGS tests, only the first test result was retained.

Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, comorbidity, underlying disease, laboratory test indicators, treatment, mNGS findings, and conventional microbiological findings were collected from the electronic medical record system. The final clinical diagnosis of PTB was made by infectious physicians or respiratory physicians based on the integration of the patient’s medical history, imaging findings, and laboratory results.

Conventional microbiological tests

Conventional microbiological tests including bacterial and fungal culture, acid-fast staining (AFS), interferon-gamma release assay (T-SPOT.TB), and GeneXpert for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, [1, 3], -β-D-glucan test (G test), and the galactomannan antigen detection test (GM test) for fungi, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for virus and antigen detection for Cryptococcus neoformans.

mNGS and bioinformatics

BALF (3–5 mL) samples were collected for metagenomic analysis. Total DNA was extracted and sequencing libraries were prepared according to the previous protocols10. DNA extraction was performed using PathoXtract WYXM03010S mcfDNA enrichment extraction kit (WillingMed, Beijing, China), which employs nucleases to remove human DNA. Sequencing was performed using a 50 bp single-end sequencing kit on the MGISEQ-200 platform (MGI Technology). Raw FASTQ-format data were processed using Fastq for quality control and evaluation. High-quality sequencing reads were aligned against the human reference genome GRCh37 (hg19) using Bowtie2 v2.4.3 to remove human host sequences. The remaining sequences were compared against the NCBI GenBank database using Kraken2 v2.1.0 to annotate and identify pathogens. Pathogens were identified based on the specific reads per ten million (RPTM value). For virus detection, an RPTM value ≥ 3 was used as the threshold, while bacteria and fungi required an RPTM ≥ 20 for positive identification. MTB was considered positive when at least one specific high quality aligned read was identified.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and independent sample t-tests were used for inter-group comparison. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and rate, and inter-group comparison were performed using chi-square tests. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of adult and elderly patients with tuberculosis

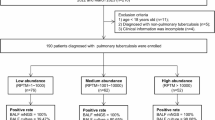

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 143 cases were included in this analysis. Patients were classified into two groups: the adult (18 ≤ age < 60, n = 66) group and the elderly (Age ≥ 60, n = 77) group (Fig. 1). The median age of the adult and elderly patients was 47 (IQR:22) and 70 (IQR:10) years, respectively (Table 1). Males patients accounted for more than 50%. The most common underlying diseases were hypertension and diabetes, with a significantly higher percentage of hypertension in the elderly group compared to the adult group (31.17% vs. 9.09%, P = 0.0012). Cough and expectoration were the most common symptoms, with no significant difference between the two groups. However, elderly patients had a higher percentages of fever (20.78% vs. 4.55%, P = 0.0044) and chest tightness (24.68% vs. 10.61%, P = 0.0297), while the adult group had a higher proportion of patients with chest pain (7.58% vs. 0%, P = 0.0139). The percentage of patients with risk factors, weakened immune, and length of hospital stay showed no significant difference between the two groups.

Regarding laboratory findings, the elderly group had higher respiratory rate (19.45 ± 1.48 vs. 18.59 ± 1.63, P = 0.0011), neutrophil percentage (NEUT%, 70.03 ± 14.29 vs. 64.27 ± 11.7, P = 0.0101), urea nitrogen (BUN, 5.09 ± 2.88 vs. 4.09 ± 1.37, P = 0.0111) and C-reactive protein (CRP, 36.31 ± 47.32 vs. 16.26 ± 31.55, P = 0.004) compared to the adult group. However, the the elderly group had lower lymphocyte levels (LY, 1 ± 0.51, P < 0.0001), lymphocyte percentage (LY%, 17.73 ± 10.8 vs. 25.07 ± 10.28, P = 0.0001) and hemoglobin (HBG, 112.39 ± 19.4 vs. 129.3 ± 17.9, P < 0.0001) compared to the adult group (Table 2).

Performance of mNGS and conventional methods for the diagnose of MTB

All 143 cases were tested using mNGS and at least one of the three conventional methods, including AFS, T-spot and GeneXpert. Compared to the clinical final diagnosis, we assessed the diagnostic performance of these methods for MTB. Results showed that mNGS has the highest positive rate (100%, 143/143), followed by T-spot (74.75%, 74/99), GeneXpert (37.80%, 48/127) and AFS (7.30%, 10/137). All the conventional methods showed slightly higher positive rates in the elderly group compared to the adult group, although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 2A). The distribution of MTB identification results for each patient is shown in Fig. 2B. Combined CMT methods identified TB only in 59.09% (39/66) of adult patients and 64.94% (50/77) of elderly patients.

MTB identification results for all the patients by mNGS, AFS, T-spot and GeneXpert. (A) Positive rate of mNGS, AFS, T-spot and GeneXpert for MTB detection in adult and elderly patients. (A) Distribution of MTB identification results for each patients. Each column represents a patient. Red bars means positive results for MTB, green bars means negative results, and white bars means not performing the related test.

Imaging findings of the adult and elderly MTB patients

Imaging results are crucial for tuberculosis diagnosis. Most patients had bilateral lung infection, with a significantly higher proportion in elderly patients compared to adults (79.22% vs. 60.61%, P = 0.0148). In contrast, single lung infections were more common in adult patient(37.88% vs. 10.39%, P = 0.0001) (Table 3). We then summarized and analyzed the features of imaging results in adult and elderly patients. Infiltration (32.17%, 46/143), shadows (26.57%, 38/143), nodules (20.28%, 29/143), and bronchiectasis (20.28%, 29/143) were the most common features. Furthermore, the frequency of several features differed significantly between the two groups. Compared to adult patients, the frequency of bronchiectasis (27.27% vs. 12.12%, P = 0.0247), emphysema (28.57% vs. 9.09%, P = 0.0034), pleural effusion (28.57% vs. 4.55%, P = 0.0002), lymph node enlargement or calcification (24.68% vs. 6.06%, P = 0.0025), pulmonary bullae (18.18% vs. 6.06%, P = 0.0294) and pericardial effusion (15.58% vs. 3.03%, P = 0.0118) was significantly higher, but the frequency of infiltration (23.38% vs. 42.42%, P = 0.0151) and nodules (12.99% vs. 28.79%, P = 0.0191) was significantly lower in the elderly patients (Table 3).

Lung microbiota of adult and elderly PTB patients

We analyzed the diversity of lung microbiota in adult and elderly PTB patients. Compared to adults, elderly patients exhibited significantly lower respiratory tract microbiota diversity (Fig. 3A). NMDS analysis of Weighted UniFrac distance showed that the microbiota in the adult group was not apart from that in the elderly group (stress = 0.2378) (Fig. 3B). ANOSIM analysis revealed significant dissimilarities between and within groups (R > 0, and P < 0.001) (Fig. 3C). MTB, Staphylococcus aureus, Veillonella parvula, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae, Corynebacterium accolens, Rothia mucilaginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Corynebacterium striatum and Streptococcus pneumoniae were the top 10 most abundant species among the patients. In adult patients, Staphylococcus aureus has the highest proportion, followed by MTB. While in the elderly group, MTB has the highest abundance, followed by Veillonella parvula, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae (Fig. 3D). The species in the “others” category were added in the supplementary Table 1. LEfSe analysis identified significant differences in microbial abundance between adult and elderly PTB patients. The LDA scores indicated that the relative abundances of Staphylococcus aureus, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Peptoniphilus lacrimalis, Neisseria subflava, Fusobacterium periodonticum, Veillonella rogoase, Gemella sanguinis, Gemella morbillorum, Streptococcus infantis, Filifactor alocis, Neisseria mucosa, and Oribacterium sinus were much more enriched in adult patients than in elderly patients, whereas the elderly patients’ microbiome was characterized by Veillonella parvula, Streptococcus vestibularis, Veillonella tobetsuensis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus and Candida albicans (LDA score > 3) (Fig. 3E).

Comparison of respiratory microbiota between adult and elderly groups. (A) Alpha diversity of each group. Statistic analysis were performed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with P < 0.05 indicates statistics significance. (B) NMDS plot, a beta diversity was calculated using the weighted unifrac distance. (C) ANOSIM boxplot based on unweighted unifrac distance. The abscissa represents all samples and each grouping, and the ordinate represents the rank of the UniFrac distance. R was between (− 1,1), and R > 0 means a significant difference of inter-groups, whereas R < 0 means the difference of intra-group was greater than that of inter-groups. P < 0.05 indicates that the statistics are significant. (D) Species-level species composition chart. (E) LEfSe analysis showed significant differences in abundant biological marker species between the adult and elderly groups. An LDA effect value of more than 3 was used as a threshold for the LEfSe analysis.

Association between clinical characteristics, imaging features, and lung microbiome in adult and elderly PTB patients

The correlation of the top 20 most abundant species and significantly different clinical characteristics and imaging features (P < 0.05) between adult and elderly patients were analyzed. Results showed that positive correlations were more common. Nine bacteria showed significantly correlation with clinical characteristics. Among them, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Corynebacterium striatum and Tropheryma whipplei was significant positively correlated with chest tightness (P < 0.05). Veillonella parvula had significant negative correlation with hypertension (P < 0.05). Streptococcus oralis had significant positive correlation with NEUT%, age, CRP, respiratory rate, fever, chest tightness and hypertension (P < 0.05). Neisseria subflava had significant positive correlation with LY% and LY, and had significant negative correlation with NEUT% (P < 0.05). Prevotella veroralis and Prevotella oris showed significant negative correlation with age (P < 0.05). Moreover, nine bacteria presented significantly correlation with imaging features. N. subflava significant negatively correlated with bilateral lung, but significant positively correlated with single lung (P < 0.05). P. aeruginosa, Rothia mucilaginosa, S. maltophilia, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. oralis and T. whipplei showed significant positive correlation with emphysema (P < 0.05). S. maltophilia and S. pneumoniae showed significant positive correlation with pleural effusion (P < 0.05). P. aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae showed significant positive correlation with lymph node enlargement (P < 0.05). S. maltophilia and Veillonella atypica showed significant positive correlation with pulmonary bullae (P < 0.05). P. aeruginosa showed significant positive correlation with pericardial effusion (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Spearman’s correlation analysis between significantly different clinical indicators and dominant microbial relative abundance at species level. The numbers display the Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r). Positive correlations are shown in red, while negative correlations are represented by blue. The correlation coefficients are proportional to the color intensity. *Significant level (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Discussion

The tuberculosis (TB) epidemic is most prevalent among the elderly, with notification rates increasing progressively with age. Moreover, the mortality rate from tuberculosis remains higher in elderly patients. In China, national TB prevalence surveys have demonstrated that older people, especially older men, have the highest prevalence of TB of all age groups11. Moreover, the diagnosis of TB in the elderly is more difficult due to nonspecific symptoms and less prominent clinical presentations. Consequently, elderly patients often require imaging and invasive procedures for definitive diagnosis. Awareness of risk factors, atypical manifestations, comorbidities, and appropriate evaluation is essential for early diagnosis of TB in elderly12. This study highlights the diagnostic value of mNGS in adult and elderly PTB patients and explored age-related differences in lung microbial composition and clinical characteristics and imaging results. Understanding these differences may aid in the early diagnosis and treatment of TB, ultimately improving patient prognosis.

Several studies have explored the diagnostic value of mNGS for TB, yet no consensus has been reached regatding its detection capacity for MTB. In Zhang et al. study, mNGS demonstrated superior performance compared to GeneXpert13. However, other studies have found that mNGS does not outperform GeneXpert in detecting MTB14,15. These discrepancies maybe influenced by factors such as sample types, whether patients undergoing anti-TB therapy, or difference in DNA extraction and host DNA depletion process within the mNGS protocol. In this study, a significant difference in the positive rate was observed between mNGS (100%) and GeneXpert (37.80%), which may largely be attributed to our preference for performing mNGS testing on patients with GeneXpert-negative results. T-spot is another commonly used TB diagnosis method which is susceptible to some factors, such as older patients, overweight and longer hospitalized16. In Liu et al. study, the positive rates of T-SPOT assay and mNGS were not statistically significant (P > 0.05)17. While Zhu et al.18 found increased performance of mNGS for TB identification compared to T-spot. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that mNGS exhibits higher sensitivity than AFS and culture for TB diagnosis17,19. In this study, mNGS (100%) demonstrated superior performance in TB detection compared to T-spot (74.75%), GeneXpert (37.80%) and AFS (7.30%), and all the conventional methods showed a slight higher positive rate in the elderly group compared to the adult group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2). Importantly, relying solely on conventional methods would have failed to diagnose all PTB cases in this study. These findings underscore the significance of employing multiple diagnostic methods, especially mNGS, for the accurate diagnosis of tuberculosis.

Rapid and precise detection of pathogenic microorganisms is crucial for the early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and accurate prognosis of infectious diseases. Compared to commonly used clinical diagnostic methods such as smear microscopy and GeneXpert, which are cost-effective (costing only a few dollars per sample) and provide results within hours, mNGS has several drawbacks. These include a longer turnaround time (approximately 24 h) and higher costs (ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars per sample). This is due to the complex processes involved in mNGS, including sample collection and pretreatment, microbial nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatics analysis, and professional interpretation of results, as well as the use of expensive instruments. However, advancements in the standardization and automation of mNGS protocols are expected to significantly reduce costs, facilitating its widespread adoption in clinical settings for rapid and accurate diagnosis.

Disruptions in the host microbiome due to multiple intrinsic or extrinsic factors render people more susceptible to TB infection. These changes lead to reduced resistance to colonization by external pathogens or the loss of commensal bacteria, leading to pulmonary disease. Analysis of the lung microbiome in TB-positive and TB-negative cases revealed that alpha diversity was lower in the TB-positive group, while beta diversity also showed significant changes, and Mycobacterium and Anoxybacillus showed highly abundant in TB-positive cases, while TB-negative cases enriched with Prevotella, Alloprevotella, Veillonella, and Gemella20. Several other studies have investigated the differences in lung microbiome composition between TB patients and healthy controls, and revealed that significantly changed microorganisms, including decrease of Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium, and increase of Lactobacillus, Acinetobacter, Mycobacterium, Staphylococcus, Neisseria, Veillonella, and Haemophilus in TB patients21,22,23. However, studies investigating the composition and differences of lung microbiota in TB patients of different ages are still lacking. In our study, the within (alpha) and between (beta) sample diversity of the PTB microbiomes showed that microbial dysbiosis in the PTB patients is closely linked to different levels of age (Fig. 3A-C). The abundance of MTB was significantly higher in the elderly group than in the adult group (Fig. 3D). Several represent species were filtered out for the adult and elderly group, and some species of Neisseria, Veillonella, and Haemophilus showed increased abundance in the elderly group (with higher TB abundance)(Fig. 3E). Compared with their abundance changing between the TB and healthy patients, the results demonstrated that these microorganisms may play an important role in determining susceptibility tuberculosis infection.

Elderly pulmonary tuberculosis is characterized by a prolonged course, reduced immune function, and multiple complications, which can cause lesions in the lung interstitium and pulmonary blood vessels in addition to lesions in the lung parenchyma. The imaging manifestations of lung lesions are often multiple, polymorphic, and atypical, complicating disease diagnosis24. Therefore, studying the imaging characteristics of elderly pulmonary tuberculosis is of great significance for the early detection, early diagnosis, and early treatment. In this study, we found the proportion of bilateral lung infection in elderly patients was significantly higher than that in adult patients. Furthermore, compared with the adult group patients, the frequency of bronchiectasis, emphysema, pleural effusion, lymph node enlargement or calcification, pulmonary bullae and pericardial effusion was significantly higher, but the frequency of infiltration and nodules was significantly lower in the elderly patients (Table 3). The incidence of bilateral lung diseases in elderly patients is often attributed to a decline in immune function with age, leading to decreased cell function and a greater susceptibility to infections and chronic lung conditions, making them more prone to developing bilateral lung diseases25. Bronchiectasis is a common lung condition that can occur as a result of PTB26. Emphysema can occur as a secondary effect of tuberculosis, causing destruction of lung tissue and resulting in reduced lung capacity27. Pleural effusion is the second most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. A previous study found that pleuritic chest pain (75%) and nonproductive cough (70%) were the most common symptoms in elderly patients with atypical cellular and biochemical features28. While in our study, the similar results were not found. Moreover, atypical radiological features, such as middle or lower lobe (rather than upper lobe) infiltrates, mass-like lesions or nodules appearing more like cancers, extensive bronchopneumonia without cavitation or nonresolving infiltrates, are frequently misdiagnosed as pneumonia or lung cancer in the elderly29. These study demonstrated that atypical imaging symptoms may also occur in elderly patients. At this time, we should pay attention to distinguishing tuberculosis from other lung diseases based on the patient’s clinical manifestations and etiological results.

Most positive correlations were found between the top 20 most abundant species, significantly different clinical characteristics, and imaging features (P < 0.05) between adult and elderly patients (Fig. 4). Among them, Streptococcus oralis showed positively correlation with age, and Prevotella veroralis and P. oris showed negative correlation with age. Previous study have revealed that Streptococcus were enriched in the PTB patients than healthy controls30. Moreover, Streptococcus were also the most frequently detected bacterial phylotype in patients with different degrees of pulmonary emphysema31. Emphysema, which was more common in elderly patients than adults, were found positively correlated with S. oralis (Fig. 4). These demonstrated that elderly patients with emphysema and enriched S. oralis maybe more susceptible to TB infection. Tett et al.. found that the distribution of Prevotella spp. is also influenced by age32. Luo et al. revealed that a decrease of Prevotella in TB patients33. These demonstrated that in TB pattients, the changing of Prevotella worth noting.

In this study, some patients have virus co-detected. Human herpesvirus 7 was the most common, followed by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), human alphaherpesvirus 1 (HSV-1), human polyomavirus 5, human herpesvirus 6B, human adenovirus subtype C, human bocavirus, and HPgV type C. Herpes virus is commonly detected in patients with lung infection34,35but the cases that cause disease are rare. Studies have found that CMV, like tuberculosis, can infect macrophages and dendritic cells. Under the influence of infection, these cells will reduce the production of IL-12, thereby disrupting the functional activity of Th1 response and aggravating the progression of tuberculosis36. In addition, Th1 response may also be mediated by the action of IL-10, and IL-10 homologues are synthesized by CMV-infected cells37. In adult tuberculosis patients, a study of adults from Russia found that the proportion of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and herpes virus co-infection was higher than that of healthy patients, indicating a link between herpes virus infection and tuberculosis38. This study did not use other detection methods to confirm whether the patients had viral infection, so the study of tuberculosis infection and viral infection is still worth conducting.

This study has several limitations, which are expected to be improved in future studies. On the one hand, we included relatively small sizes of cohorts, mainly because this is a single-center retrospective study. On the other hand, we included only samples with positive mNGS tuberculosis test results, which introduced a certain degree of bias and may have led to a biased assessment of the diagnostic performance of various methods. Finally, due to the long treatment period and difficulty in follow-up of tuberculosis patients, the use of antibiotics and treatment effects were not evaluated.

Conclusion

Significant differences in clinical characteristics, lung imaging characteristics, and lung microbial composition were observed between adult and elderly PTB patients. Understanding these age-related differences can provide valuable insights for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, and provide support for improving patients prognosis .

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database with a BioProject ID of PRJNA1197168 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1197168?reviewer=3aeh4mnnbua4gp65emktbthfgb).

References

Li, T. et al. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in china: A National survey. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.12.005 (2023).

Organization, W. H. (World Health Organization, 2023).

Dong, Z. et al. Age-period-cohort analysis of pulmonary tuberculosis reported incidence, China, 2006–2020. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 11, 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-01009-4 (2022).

King, A. Exploring the lung microbiome’s role in disease. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01123-3 (2024).

Gu, W., Miller, S. & Chiu, C. Y. Clinical metagenomic next-generation sequencing for pathogen detection. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 14, 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012751 (2019).

Gu, W. et al. Rapid pathogen detection by metagenomic next-generation sequencing of infected body fluids. Nat. Med. 27, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1105-z (2021).

Blauwkamp, T. A. et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a microbial cell-free DNA sequencing test for infectious disease. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0349-6 (2019).

Taş, N. et al. Metagenomic tools in microbial ecology research. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 67, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2021.01.019 (2021).

Schlaberg, R. & Microbiome diagnostics Clin. Chem. 66, 68–76 https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2019.303248 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Clinical evaluation of cell-free and cellular metagenomic next-generation sequencing of infected body fluids. J. Adv. Res. 55, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.02.018 (2023).

Caraux-Paz, P., Diamantis, S., de Wazières, B. & Gallien, S. Tuberculosis in the elderly. J. Clin. Med. 10, 5888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10245888 (2021).

Vishnu Sharma, M., Arora, V. K. & Anupama, N. Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in elderly. Indian J. Tuberculosis. 69, 205–S208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtb.2022.10.001 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. DdPCR provides a sensitive test compared with GeneXpert MTB/RIF and mNGS for suspected Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1216339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1216339 (2023).

Shi, C. L. et al. Clinical metagenomic sequencing for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Infect. 81, 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.004 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Tuberculosis diagnosis by metagenomic next-generation sequencing on Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: A cross-sectional analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 104, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.063 (2021).

Pan, L. et al. Risk factors for false-negative T-SPOT.TB assay results in patients with pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB. J. Infect. 70, 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2014.12.018 (2015).

Liu, Y., Wang, H., Li, Y. & Yu, Z. Clinical application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in tuberculosis diagnosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 984753. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.984753 (2023).

Zhu, N., Zhou, D. & Li, S. Diagnostic accuracy of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in sputum-scarce or smear-negative cases with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021 (9970817). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9970817 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. The value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculous using Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Lab. Med. 55, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/lmad041 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. Metagenomic analysis of the lung Microbiome in pulmonary tuberculosis—a pilot study. Emerg. Microbes Infections. 9, 1444–1452. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1783188 (2020).

Vázquez-Pérez, J. A. et al. Alveolar microbiota profile in patients with human pulmonary tuberculosis and interstitial pneumonia. Microb. Pathog. 139, 103851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103851 (2020).

Nakhaee, M., Rezaee, A., Basiri, R., Soleimanpour, S. & Ghazvini, K. Relation between lower respiratory tract microbiota and type of immune response against tuberculosis. Microb. Pathog. 120, 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.054 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Correlation between either Cupriavidus or Porphyromonas and primary pulmonary tuberculosis found by analysing the microbiota in patients’ Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. PLoS One. 10, e0124194. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124194 (2015).

Lv, Y. et al. The high-resolution CT imaging of active secondary pulmonary tuberculosis in the primary therapy. Chin. J. Exp. Clin. Infect. Dis. (Electron. Ed.). 9, 71–75 (2015).

Schneider, J. L. et al. The aging lung: Physiology, disease, and immunity. Cell 184, 1990–2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.005 (2021).

Ko, J. M., Kim, K. J., Park, S. H. & Park, H. J. Bronchiectasis in active tuberculosis. Acta Radiol. 54, 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113475796 (2013).

Joshi, A., Su, L. J. & Orloff, M. S. Tuberculosis and risk of emphysema among US adults in the NHANES I epidemiologic Follow-Up study cohort, 1971–1992. Epidemiologia (Basel). 4, 525–537. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia4040044 (2023).

Berger, H. W. & Mejia, E. Tuberculous pleurisy. Chest 63, 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.63.1.88 (1973).

Lee, J. H., Han, D. H., Song, J. W. & Chung, H. S. Diagnostic and therapeutic problems of pulmonary tuberculosis in elderly patients. J. Korean Med. Sci. 20, 784–789. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2005.20.5.784 (2005).

Shahzad, M. et al. The oral Microbiome of newly diagnosed tuberculosis patients; A pilot study. Genomics 116, 110816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2024.110816 (2024).

Naito, K. et al. Bacteriological incidence in pneumonia patients with pulmonary emphysema: A bacterial floral analysis using the 16S ribosomal RNA gene in Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 12, 2111–2120. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S140901 (2017).

Tett, A., Pasolli, E., Masetti, G., Ercolini, D. & Segata, N. Prevotella diversity, niches and interactions with the human host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00559-y (2021).

Luo, M. et al. Alternation of gut microbiota in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Front. Physiol. 8, 822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00822 (2017).

Xie, G. et al. Exploring the clinical utility of metagenomic Next-Generation sequencing in the diagnosis of pulmonary infection. Infect. Dis. Ther. 10, 1419–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00476-w (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Impact of herpesvirus detection via metagenomic Next-Generation sequencing in patients with lower respiratory tract infections. Infect. Drug Resist. 18, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.2147/idr.S484768 (2025).

Rölle, A. & Olweus, J. Dendritic cells in cytomegalovirus infection: Viral evasion and host countermeasures. Apmis 117, 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02449.x (2009).

McNab, F. W. et al. Type I IFN induces IL-10 production in an IL-27-independent manner and blocks responsiveness to IFN-γ for production of IL-12 and bacterial killing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages. J. Immunol. 193, 3600–3612. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1401088 (2014).

Kazanova, A. S., Lavrov, V. F. & Panteleev, A. V. Association of tuberculosis and infections of herpes simplex, varicella Zoster viruses and cytomegalovirus. Epidemiol. Vaccinal Prev. 14, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.31631/2073-3046-2015-14-4-23-28 (2015).

Funding

This work was supported by the Quzhou City science and technology plan project (No. 2023K146).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SGW progressed experimental design, data collection, and manuscript writing and revising. SW, ZYW, MQC, XCC and DL revised the manuscript. CXP contributed to the study conception and design, revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Quzhou Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Quzhou People’s Hospital. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of The Quzhou Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Quzhou People’s Hospital waived the need of obtaining informed consent. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all data were anonymous before analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Wang, S., Wu, Z. et al. Comparative analysis of the clinical characteristic and lung microbiota in adult and elderly patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Sci Rep 15, 19777 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04970-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04970-w