Abstract

Liquids irradiated with nonequilibrium atmospheric pressure plasma exert antitumor effects. Here, we produced plasma-activated acetated Ringer (PAA) and plasma-activated sodium acetate (PASA) solutions, each at 1%, 3%, and 5% mass concentrations. We evaluated the antitumor effects of PAA and PASA on gastric cancer (GC). Two GC cell lines (MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc) as well as normal human peritoneal mesothelial cells were subjected to cell viability assays using PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA. To elucidate the functional mechanisms, we examined morphological changes induced by 3% PASA following 10 min of irradiation. To further elucidate the underlying biological processes, we compared the expression of apoptosis-related proteins following the administration of 3% sodium acetate solution without plasma exposure and 3% PASA irradiated for 10 min. Additionally, MKN45-Luc cells were intraperitoneally injected into mice, followed by intraperitoneal administration of acetated Ringer’s solution without plasma exposure (control-1 group), 3% sodium acetate solution without plasma exposure (control-2 group), and 3% PASA irradiated for 10 min (treatment group). Peritoneal dissemination was observed using in vivo bioluminescent imaging and laparotomy. PAA and PASA achieved an antitumor effect in a sodium acetate concentration-dependent manner. PAA and 3% PASA caused significantly less damage to normal peritoneal mesothelial cells compared to GC cells at 5 and 10 min of plasma exposure (p < 0.001). Blebs, indicative of apoptosis, were observed at 1.5 h after 3% PASA treatment in GC cells. 3% PASA treatment increased the expression of phosphorylated MKK3/MKK6 and phosphorylated p38 MAPK, suggesting that apoptosis may be mediated through the p38 MAPK pathway. The intraperitoneal administration of 3% PASA significantly reduced the number of peritoneal nodules, and no adverse events were detected. Here we show that PASA exerted an antitumor effect on GC, indicating that the intraperitoneal administration of 3% PASA may serve as a novel treatment for the peritoneal dissemination of GC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of death worldwide1. The most frequent pattern of distant metastatic recurrence after gastrectomy is peritoneal dissemination, for which systemic chemotherapy is the first-line treatment2,3,4,5,6,7. Diverse molecular targeted drugs are used in clinical practice8,9,10,11,12. However, their efficacies are very limited because of drug resistance and poor drug delivery to cancer cells13,14,15,16. Therefore, it is necessary to explore alternative approaches to cancer treatment. In this study, we focused on the antitumor effects of plasma as a potential cancer treatment strategy.

Plasma, which is referred to as “the fourth state of matter” besides solids, liquids and gases, resides in a high-energy state comprising negatively charged electrons, positive ions, free radicals, excited molecules, and energetic photons17. Recently, nonequilibrium atmospheric pressure plasma (NEAPP), which is generated at low temperatures under atmospheric pressure, has been applied in the medical field18. In particular, liquids irradiated with NEAPP exert antitumor effects19,20,21,22.

Plasma-activated medium (PAM), a culture medium irradiated with NEAPP, has demonstrated antitumor effects on glioblastoma23. It was shown that PAM selectively targeted glioblastoma cells without affecting normal astrocytes23. Additionally, PAM exhibited antitumor activity against ovarian cancer, and intraperitoneal administration of PAM in mice suppressed peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer20,24,25. However, the safety of the culture medium for administration to humans is not established, and identifying a simpler and more practical solution represents a future challenge. Next, lactated Ringer’s solution, which can be administered to humans, attracted attention as an alternative to the culture medium. Plasma-activated lactated Ringer’s solution (PAL) has been shown to exert an antitumor effect on glioblastoma in vitro, and PAL administration inhibited tumor formation in a mouse subcutaneous tumor model of cervical cancer19. Furthermore, intraperitoneal lavage with PAL significantly improved overall survival rates in a peritoneal dissemination mouse model of ovarian cancer26. The intraperitoneal administration of PAM and PAL to mouse xenograft models of GC and pancreatic cancer, respectively, inhibits the peritoneal dissemination of these tumors27,28.

The development of PAL may therefore indicate the clinical potential of plasma-activated solutions. However, it is difficult to completely control peritoneal dissemination using intraperitoneal administration of PAL thus requiring new plasma-activated solutions with potentially stronger antitumor effects without increasing toxicity28. Furthermore, the mechanism of the antitumor effects of plasma-activated solutions remains to be fully determined, and it remains unclear how the chemical compositions in solutions are changed by plasma exposure.

It has been previously reported that plasma-activated acetate Ringer’s solution (PAA) exerts an antitumor effect on the human ovarian cancer cell line SK-OV-3 and the breast cancer cell line MCF-719,29. The antitumor effect of PAA on gastrointestinal cancers has not been previously reported. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the antitumor effect of PAA on gastric cancer. Additionally, to test the hypothesis that a stronger antitumor effect could be achieved by increasing the concentration of sodium acetate, we sought to examine whether plasma-activated sodium acetate (PASA) solutions at 1%, 3%, and 5% mass concentrations—higher than the 0.23% mass concentration of PAA—would exert a more potent antitumor effect. Furthermore, we investigated whether the concentrations of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), electrolytes, and organic substances were changed by plasma exposure. Moreover, we evaluated the efficacy of 3% PASA in mouse xenograft models of peritoneal dissemination of GC. In this study, PAL is defined as plasma-activated lactate Ringer’s solution, PAA as plasma-activated acetate Ringer’s solution, and PASA as plasma-activated sodium acetate solution.

Results

Preparation of PAL, PAA, and PASA

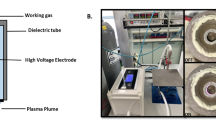

A published experimental system used to produce plasma-activated liquids is shown in Fig. 1a27,28. Briefly, flowing argon gas is ionized by applying 10 kV from a 60-Hz commercial power supply to two electrodes 20-mm apart at atmospheric pressure and room temperature, and the medium was exposed to the plasma jet (Supplementary File 1). The flow rate of the argon gas was set to 2.0 standard liters/min. Here, L represents the distance between the plasma source and medium, T represents the plasma exposure time, and V presents the volume of the irradiated medium. L was fixed at 3 mm, and V at 6 ml. T was changed according to each assay. Lactated Ringer’s solution (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), acetated Ringer’s solution (neo CritiCare Pharma Co., Ltd), or sodium acetate solution (1%, 3%, 5%) were treated with plasma. The composition of each solution before plasma exposure is shown in Table 1. Undiluted plasma-activated solutions were used.

(a) The experimental system employed to produce plasma-activated liquids. L represents the distance between the plasma source and medium, and V represents the volume of the irradiated medium. In this experiment, L was fixed at 3 mm, and V at 6 ml. (b) Antitumor effects of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA on GC cell lines. PASA had stronger antitumor effects at T = 0.5, 1, and 3 min compared with PAL. (c) Effects of PAL, PAA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA on human peritoneal mesothelial cells. PAA and 3% PASA caused much less damage to normal peritoneal mesothelial cells compared with PAL. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Antitumor effects of PAL, PAA, and PASA on GC cells

The antitumor effects of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA on MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells are shown in Fig. 1b. Plasma-activated solutions tended to suppress cell viability in a time-dependent manner. Moreover, in the presence of PAA and PASA, cell viability was inhibited in a sodium acetate concentration-dependent manner. 1%PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA achieved significantly stronger antitumor effects compared with PAL, particularly at T of 0.5, 1, and 3 min compared with PAL (p < 0.05). IT50 was defined as the plasma exposure time at which 50% of cancer cells were inhibited, in accordance with the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). IT50 is indicated in Table 2, which shows that the IT50 values of PAA and PASA were lower compared with that of PAL; and in particular, 3% PASA and 5% PASA achieved strong antitumor effects at T = 1 min. Each plasma-activated solution showed approximately the same antitumor effect on 5 × 104 of MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells at T = 10 min.

Effects of plasma-activated solutions on human peritoneal mesothelial cells

The effects of PAL, PAA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA on the human peritoneal mesothelial cells were compared with those on GC cells (Fig. 1c). In PAL, the cell viability rate of normal peritoneal mesothelial cells was slightly higher compared with that of GC cells, while in PAA normal peritoneal mesothelial cells suffered much less damage compared with GC cells. In 3% PASA, cancer cell viability rates were significantly lower than those of normal peritoneal mesothelial cells at T = 1, 5, and 10 min (p < 0.001). For 5% PASA, while normal peritoneal mesothelial cells sustained considerable damage at T = 10 min, cancer cell viability remained significantly lower than that of normal peritoneal mesothelial cells at T = 1 and 5 min (p < 0.001).

Apoptosis induced by 3% PASA treatment on GC cells

The percentages of live, apoptotic, and dead cells after 3% PASA treatment are shown in Fig. 2a. The percentages of apoptotic plus dead MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells increased significantly at T = 3 min. In particular, the percentages of apoptotic plus dead MKN45-Luc cells were approximately 70% at T ≥ 3 min or longer. Furthermore, MKN45-Luc cells were more sensitive to 3% PASA treatment compared with MKN1-Luc cells. On the other hand, in normal peritoneal mesothelial cells, the percentage of apoptotic and dead cells at T ≥ 3 min did not change significantly, suggesting that 3% PASA exhibits favorable cell selectivity.

(a) Apoptosis assay of normal peritoneal mesothelial cells and GC cells treated with 3% PASA. The percentages of apoptotic plus dead MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells increased within T = 3 min. (b) Morphological change induced by 3% PASA treatment. Morphological changes in MKN45-Luc cells by treatment with 3% sodium acetate solutions without plasma exposure (control group) or 3% PASA for T = 10 min (treatment group) were observed using time-lapse photography. In the treatment group, numerous blebs, indicative of apoptosis, were observed around the cells (arrow).

Morphological change induced by 3% PASA treatment of GC cell lines

Morphological changes of MKN45-Luc cells induced by 3% sodium acetate solutions without plasma exposure (control group) or 3% PASA for T = 10 min (treatment group) were observed using time-lapse photography (Supplementary File 2 and 3). In the control group, cell morphology remained virtually unchanged over the 12-h observation period. In contrast, cell deformity in the treatment group was observed 1-h after treatment. Blebs, small blister-like protrusions of the plasma membrane, began to emerge at 1.5 h, and the cells were surrounded with numerous blebs at 6 h (Fig. 2b).

H2O2 and NO2 − generation in plasma-activated solutions

The H2O2 and NO2− concentrations of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA are shown in Fig. 3a. The H2O2 and NO2− concentrations of each plasma-activated solution increased approximately linearly with increasing plasma exposure time. The H2O2 concentrations of PAL, PAA, 1%PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA at T = 10 min were 4376 µM, 4447 µM, 2871 µM, 2400 µM, and 2447 µM, respectively. Moreover, the NO2− concentrations of PAL, PAA, 1%PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA at T = 10 min were 3739 µM, 3913 µM, 4348 µM, 4261 µM, and 5130 µM, respectively.

(a) H2O2 and NO2- concentrations of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA. H2O2 and NO2- concentrations of each plasma-activated solution increased approximately linearly with increasing plasma exposure time. (b) Na+, K+, glucose, and lactate concentrations of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA. Glucose and lactate were not originally present in acetated Ringer’s and sodium acetate solutions without plasma exposure but were newly generated after plasma exposure. (c) Simple Western assay of MKN1-Luc and MKN-45-Luc cells treated with 3% sodium acetate solution without plasma exposure (control group) or 3% PASA at T = 10 min (treatment group). The expressions of phosphorylated MKK3/MKK6 and phosphorylated p38 MAPK were increased in the treatment group.

Changes in electrolytes and organic substances of plasma-activated solutions

The concentrations of Na+, K+, glucose, and lactate in PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA are shown in Fig. 3b. The concentrations of Na+ and K+ increased in PAL and PAA as the plasma exposure time increased. In PASA, the Na+ concentration increased with plasma exposure time. K+ was not present in sodium acetate solutions without plasma exposure and did not change after plasma exposure. In all solutions, glucose was not originally detected without plasma exposure but was subsequently generated; and the glucose concentration increased with increasing plasma exposure time. Moreover, lactate was not present in acetated Ringer’s and sodium acetate solutions, but was generated after plasma exposure. The concentration of lactate increased as the plasma exposure time increased.

The activation of p38 MAPK pathway by 3% PASA

Representative blots and quantifications are shown in Fig. 3c. In both cell lines, phosphorylated MKK3/MKK6 and phosphorylated p38 MAPK levels were higher in the treatment group than in the control group.

Antitumor effect of 3% PASA on a mouse model of peritoneal dissemination of GC

The antitumor effect of 3% PASA was investigated in mouse models of peritoneal dissemination using MKN45-Luc cells. Experimental protocol is shown in Fig. 4a and IVIS imaging is shown in Fig. 4b. On days 8 and 12, the treatment group generated significantly fewer light signals detected using bioluminescent imaging than the control-1 and control-2 groups. The laparotomy findings on day 12 are shown in Fig. 4c. Injection site reactions, abnormal adhesions in the abdominal cavity, and inflammation at the peritoneal wall (e.g. wall thickness or redness) were not observed macroscopically. The average weight of peritoneal nodules in the treatment group was lower than that in the control-1 and control-2 groups (control-1 group: 0.115 ± 0.054 g, control-2 group: 0.082 ± 0.039 g, treatment group: 0.055 ± 0.047 g). Moreover, the average number of peritoneal nodules in the treatment group was significantly smaller than that in the control-1 and control-2 groups (control-1 group: 5.0 ± 1.8; control-2 group: 5.2 ± 2.1; treatment group: 1.2 ± 1.0).

Antitumor effect of 3% PASA on mouse xenograft models of peritoneal dissemination of GC. The intraperitoneal administration of 1.5 mL of acetated Ringer’s solution without plasma exposure (control-1 group), 3% sodium acetate solution without plasma exposure (control-2 group), or 3% PASA with a 10-min plasma exposure (treatment group) was performed on days 1–4 and 8–11. (a) Experimental protocol. (b) IVIS imaging data. (c) Laparotomy findings. The average number of peritoneal nodules in the treatment group was significantly smaller than that in the control-1 and control-2 groups. *P < 0.05. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Discussion

In the field of cancer treatment, liquids irradiated by NEAPP were extended to include PAM to PAL with the aim of applying them to treat patients19,21,22,27,28. In the previous study, we showed that intraperitoneal administration of PAL inhibited formation of peritoneal nodules to some degree in mouse xenograft models of peritoneal dissemination of pancreatic cancer28. However, it was difficult to completely suppress peritoneal nodules using PAL under the strongest condition (L = 3 mm, T = 10 min, V = 8 ml, dose = 2.5 ml). It has been previously reported that PAA exerts an antitumor effect on the human ovarian cancer cell line SK-OV-3 and the breast cancer cell line MCF-719,29. Therefore, we attempted to apply PAA to the treatment of gastric cancer.

Lactated Ringer’s solution contains the components as follows: NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, and L-sodium lactate. Only L-sodium lactate achieved antitumor effects, in contrast to NaCl, KCl, CaCl219. Accordingly, we reasoned that among NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, and CH3COONa in acetated Ringer’s solution, CH3COONa is most likely associated with an antitumor effect. Furthermore, we expected that the antitumor effect could be enhanced using higher concentrations of sodium acetate solution compared with those of acetated Ringer’s solution. Acetated Ringer’s solution contains approximately 0.23% CH3COONa, and we determined how the antitumor effects were altered using 1%, 3%, and 5% sodium acetate solutions.

Cell viability assays are typically performed using larger cell numbers (50,000 cells/200 µl/well) to focus on the enhancement of the antitumor effect27,28. The antitumor effects of MKN1-Luc cells were enhanced as a function of increasing sodium acetate concentrations. The antitumor effects of MKN45-Luc cells were enhanced with increasing concentrations up to 3%, although the antitumor effects of 3% PASA and 5% PASA were nearly equivalent. In particular, PAA and PASA achieved stronger antitumor effects on MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells compared with PAL within T = 3 min. The antitumor effects of 3% PASA and 5% PASA were considered to reach equilibrium at T = 1 min under this condition (5 × 104 cells; dose, 200 µl; treatment time, 1 h).

It is critically important for cancer therapeutics to selectively act on cancer cells with minimal adverse effects on surrounding normal tissues. For example, PAM selectively inhibits glioblastoma and ovarian cancer cells in cell viability assays23,25and it was reported that the human fibroblast cell line WI38 is more tolerant of PAM compared with GC cell lines22. Assuming intraperitoneal administration, the selective antitumor effects of PAA and PASA were evaluated by comparing the cell viability rates of cancer cell lines and normal peritoneal mesothelial cells that cover the abdominal cavity. The cell viability rates of peritoneal mesothelial cells were higher compared with GC cells in each plasma-activated solution, except for 5% PASA at T = 10 min. Notably, PAA and 3% PASA exhibited greater differences in cell viability rates between peritoneal mesothelial cells and GC cells compared with PAL, suggesting that they may achieve higher selective antitumor effects.

NEAPP exerts antitumor effects on cancer cells by inducing apoptosis24,30,31. Annexin V binds phophatidylserine exposed on the cell surface during apoptosis, and flow cytometric analysis of annexin V positive cells revealed that populations of MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells migrated counterclockwise with increasing exposure time within T = 3 min, indicating apoptotic progression32. The ratio of apoptotic cells plus dead cells to live cells was approximately constant after T = 3 min, suggesting that apoptosis reached equilibrium at T = 3 min under this condition (2 × 105 cells; dose, 150 µl; treatment time, 1 h; apoptosis evaluation time, 2 h after treatment terminated). The term “equilibrium” is used here to describe this threshold. Identifying the plasma exposure time required to reach equilibrium could serve as a valuable benchmark for comparing the antitumor efficacy of different plasma-activated solutions. Moreover, if the antitumor effects at T = 3 min and T = 10 min are comparable, opting for T = 3 min would allow for shorter production times and potentially fewer adverse events compared to T = 10 min. Thus, analyzing the plasma exposure time to achieve equilibrium is a meaningful endeavor. Furthermore, time-lapse photography detected morphological changes in cancer cells treated with 3% PASA, and blebs, characteristic of apoptosis, appeared around the cells 1.5-h after treatment. Moreover, the cells were surrounded with numerous blebs 6-h after treatment, after which significant morphological changes were not observed. Therefore, we estimated that apoptosis was induced immediately after the treatment with 3% PASA and was completed < 6 h after treatment.

The duration of antitumor effects is important for the application of NEAPP to cancer therapy. For example, Previous studies have reported that the antitumor effect of plasma-activated solutions diminishes over time after thawing19. For example, the effectiveness of PAM on glioblastoma lasts between 8 and 18 h, with the antitumor effect disappearing entirely after 18 h19. To achieve the desired antitumor outcome, apoptosis must be induced before this effect fades. In this study, apoptosis was observed as early as 1.5 h after 3% PASA treatment, which we consider an advantage due to the rapid onset of the antitumor effect.

Our knowledge of the mechanism of apoptosis induced by plasma is incomplete, although evidence indicates that RONS generated by plasma are involved in apoptosis33. For example, Sato et al. found that cellular uptake of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induces apoptosis of tumor cells. Moreover, Sasaki et al. found that ROS triggers physiological Ca2+ influx through transient receptor potential channels34,35,36.

Among RONS, H2O2 plays an important role in cell death34. NO2− is another RONS, and Kurake et al. reported that NO2− alone did not achieve an antitumor effect on glioblastoma cells, although it synergistically enhanced the antitumor effect of H2O237. In the present study, the concentrations of H2O2 and NO2− in each plasma-activated solution increased approximately in proportion to the plasma exposure time; and RONS are likely significantly associated with the enhancement of the antitumor effect with increasing plasma exposure time. However, 3% PASA and 5% PASA achieved stronger antitumor effects at T = 1 min compared with PAL, while the H2O2 and NO2− concentrations of 3% PASA and 5% PASA at T = 1 min were approximately the same as those of PAL, making it difficult to explain the antitumor effects of plasma only in terms of RONS such as H2O2 or NO2−.

To clarify these issues, we investigated whether the concentrations of the electrolytes and organic substances were changed by plasma exposure. The concentrations of Na+ and K+ in each plasma-activated solution increased with increasing plasma exposure time. Plasma irradiation evaporates water, and 6-ml decreases to 5.8-ml after 1 min, 5.6-ml after 3 min, 4.9-ml after 5 min, and 4.3-ml after 10 min. The changes in Na+ and K+ concentration were approximately inversely proportional to the changes in the volumes of the solutions, suggesting that the increases in Na+ and K+ concentration were attributable to the volumes of the solutions. In contrast, glucose and lactate were not originally present in acetated Ringer’s or sodium acetate solutions and were therefore possibly newly generated by plasma exposure.

Furthermore, the increases in glucose and lactate concentrations with increasing plasma exposure time significantly exceeded the decrease in the volumes of the solutions. This may be explained because acetate ion (CH3COO−) was converted to glucose (C6H12O6) or lactate (C3H5O3−) by plasma exposure. For example, Tanaka et al. reported that acetate, formate, pyruvate, glycoxylate and 2,3-dimethyltartrate are produced by plasma irradiation in lactated Ringer’s solution, and 2,3-dimethyltartrate exert cytotoxic effects on glioblastoma cells, but not on normal astrocytes19,38. In addition, Miron et al. reported that plasma-derived compounds, such as acetic anhydride and ethyl acetate in PAA have the potential to play important roles in plasma-based cancer therapy29. We therefore reasoned that acetate ion is also converted to other organic substances with antitumor effects by plasma exposure.

The Simple Western assay revealed that the expressions of phosphorylated MKK3/MKK6 and phosphorylated p38 MAPK in MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells were increased following the administration of 3% PASA. p38 MAPK is a known mediator of apoptosis39. Previous studies have reported that NEAPP induces apoptosis via the p38 MAPK pathway in malignant glioblastoma40. Matsushita et al. also demonstrated that RONS activate the MAPK pathway, inducing apoptosis41. Based on these findings and our results, we hypothesize that RONS may activate the p38 MAPK pathway, leading to apoptosis.

In vitro experiments showed that the cell viability of cancer cells was inhibited in a time-dependent and a sodium acetate concentration-dependent manner. In addition, 3% PASA for T = 10 min caused less damage to human peritoneal mesothelial cells compared to 5% PASA for T = 10 min. Therefore, we selected 3% PASA for T = 10 min in mouse xenograft models of peritoneal dissemination of GC to assess antitumor effects. The treatment group emitted significantly fewer light signals, detected using bioluminescent imaging, and a significantly smaller number of peritoneal nodules than the control groups. Furthermore, none of the mice in the treatment group died during the observation period, and weight changes in the treatment group did not significantly differ from those in the control groups. Therefore, we propose thought that 3% PASA may serve as a new treatment for peritoneal dissemination of GC.

Plasma studies on gastrointestinal cancers in our laboratory demonstrate the efficacy of PAM and PAL, respectively, on mouse models of peritoneal dissemination of GC and pancreatic cancer27,28. Moreover, here we demonstrate the efficacy of intraperitoneal administration of 3% PASA on mouse models of peritoneal dissemination of GC. To directly expose cancer cells to PAM and PAL, we reasoned that it may be desirable to first intraperitoneally administer plasma-activated solutions for peritoneal dissemination encountered in clinical practice.

The present study has several limitations. First, PASA controlled the cell viability of cancer cells in vitro, although incompletely in vivo. The nature of the tumor microenvironment, among other factors, may explain the inadequate control of peritoneal dissemination in vivo. Isolated tumor cells do not exist in situ, and in the tumor microenvironment, tumor cells are covered with stromal cells such as fibroblast as well as with components of the extracellular matrix42. In vitro experiments employ pure populations of cancer cells, and PASA directly acts on them. In contrast, the surrounding stroma in vivo likely prevents their interaction with PASA. Thus, intraperitoneal administration of PASA may suppress microscopic metastasis (positive lavage cytology, CY+) in patients at high risk of peritoneal dissemination, such as those with type 4 or giant type 3 GC. In contrast, PASA alone was insufficiently effective for treating mature peritoneal nodules and systemic metastasis. It will therefore be necessary to develop plasma-activated solutions with stronger antitumor effects or to evaluate whether the antitumor effects of plasma-activated solutions can be enhanced in combination with cytotoxic anticancer drugs or immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Second, an in vivo experiment was performed employing a dose of 1.5-ml PASA and dosing schedules of days 1–4 and days 8–11, although more detailed monitoring of oncological effects and chemical side effects of PASA may help determine the optimal dose and administration interval. Third, the concentrations of glucose and lactate were measured using an ABL800 FLEX system which is an instrument specialized in analyzing blood samples. In addition, organic substances with antitumor effects were not identified here. Therefore, further analysis is needed to determine the changes in organic substances after plasma exposure.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that PAA and PASA exhibit antitumor effects on GC, with the efficacy increasing proportionally to the concentration of sodium acetate. Furthermore, apoptosis was observed to occur rapidly following the administration of 3% PASA. Evidence suggests that the mechanism of apoptosis involves the activation of the p38 MAPK pathway mediated by RONS. The intraperitoneal administration of 3% PASA may therefore serve as a novel treatment for the peritoneal dissemination of GC.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (2013) Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. The Animal Research Committee of Nagoya University approved the experiments using animals (approval no. 28210). The animal study was carried out in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Cell lines and culture conditions

Human GC cell lines MKN1-Luc (RRID: CVCL_J261) and MKN45-Luc (RRID: CVCL_J262) were purchased from the Japanese Cancer Research Resources Bank (Tokyo, Japan), and human peritoneal mesothelial cells were from KAC Co., Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan). MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Corning, Inc. Corning, NY, USA) and Gibco™ Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Human peritoneal mesothelial cells were maintained using a Mesothelial Cell Medium Kit (Innoprot Ref# P60167) supplemented with 15% FBS (Corning, Inc.).

Cell viability assay

A cell viability assay was performed to compare the antitumor effects of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA (T = 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, or 10 min). MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells (5 × 104/200 µl/well) were seeded into 96-well plates in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS. The medium was replaced with 200 µl of each solution the following day. After treatment for 1 h, each solution was replaced with 200 µl of fresh medium containing 10% FBS. The next day, cell viability was analyzed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The absorbance values represent the average of six independent experiments. Furthermore, to evaluate the effect of each plasma-activated solution on the normal human peritoneum, a cell viability assay was performed using human peritoneal mesothelial cells as described above.

Apoptosis assay

Normal peritoneal mesothelial cells, MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells (2 × 105/500 µl/well) were seeded into 24-well plates. The next day, the medium was replaced with 150 µl of 3% PASA irradiated by plasma (T = 0, 1, 3, 5, or 10 min). After 1-h treatment, PASA was replaced with culture medium, and 2-h later, the numbers of live, apoptotic, and dead cells were measured using a Muse™ Annexin V & Dead Cell Kit (MCH100105, Luminex, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Time-lapse photography

MKN45-Luc cells (5 × 104/500 µl/well) were seeded into 24-well plates. The next day, the medium was replaced with 250 µl of medium plus 250 µl of 3% sodium acetate irradiated using plasma (T = 10 min), or with 250 µl of medium plus 250 µl of 3% sodium acetate, without plasma exposure, as a control. Immediately after treatment, time-lapse photography was performed at 5 min intervals using a BZ810 microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan), and morphological changes in MKN45-Luc cells were noted.

Measuring components of plasma-treated solutions

H2O2 and NO2- concentrations of PAL, PAA, 1% PASA, 3% PASA, and 5% PASA (T = 1, 5, 10 min) were measured using a DPM2-CIO-DP (Kyoritsu Chemical-check Lab., Corp., Yokohama, Japan). Furthermore, to investigate compositional changes after plasma exposure, the concentrations of Na+, K+, glucose, and lactate in each solution (T = 1, 5, 10 min) were measured using an ABL800 FLEX system (Radiometer Medical ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark). The concentrations of Na+ and K+ are measured using the potentiometric method, while glucose and lactate concentrations are determined by the amperometric method. The concentration of H2O2 is assessed via a spectrophotometric method using potassium iodide, and NO2- concentration is measured by spectrophotometry using naphthylethylenediamine.

Intracellular pathway analysis

To investigate the effects of PASA on intracellular pathways, apoptosis-related proteins were analyzed using the Simple Western assay system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA). MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells (2 × 10⁵ cells/2 ml/well) were seeded into 6-well plates. After 72 h, the medium was replaced with either 1 ml of medium plus 1 ml of 3% PASA irradiated for 10 min (treatment group) or 1 ml of medium plus 1 ml of 3% sodium acetate solution without plasma exposure (control group). Total proteins were extracted 1 h later.

Aliquots of 3 µg of total protein extracted from MKN1-Luc and MKN45-Luc cells were probed with the primary monoclonal antibodies from the Phospho-p38 MAPK Pathway Antibody Sampler Kit (#9913). Protein expression levels were normalized to β-actin, and data were analyzed using Compass for Simple Western software (ProteinSimple).

Animal studies

Six-week-old male BALB/c S1c-nu/nu mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). Fifteen mice were equally divided into the groups as follows: control-1 group (5 mice, acetated Ringer’s solution without plasma exposure), control-2 group (5 mice, 3% sodium acetate solution without plasma exposure), or treatment group (5 mice, 3% PASA irradiated with plasma for 10 min). MKN45-Luc cells (2 × 106) were intraperitoneally injected through the left lower quadrant of the abdominal wall. The intraperitoneal administration of 1.5 ml of each solution was performed on days 1–4 and 8–11. The mice were sacrificed using 100% CO2 for 5 min on day 12. Peritoneal-dissemination nodules were evaluated using an IVIS Spectrum In Vivo Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA) on days 1, 8, and 12; and laparotomy findings were acquired on day 12. D-luciferin (150 mg/kg, Caliper Life Sciences) was intraperitoneally injected into mice subjected to the IVIS analysis.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were compared between two groups using the Mann–Whitney test and among three groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical analysis was performed using R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and EZR software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan)43. EZR software is built on R software and integrates various analysis functions commonly used in medical statistics, such as survival analysis, ROC curve analysis, and meta-analysis, through the customization capabilities of R Commander. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Data availability

The data that support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Smyth, E. C., Nilsson, M., Grabsch, H. I., van Grieken, N. C. & Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. Lancet 396, 635–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31288-5 (2020).

Shiozaki, H. et al. Prognosis of gastric adenocarcinoma patients with various burdens of peritoneal metastases. J. Surg. Oncol. 113, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.24087 (2016).

Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer 24, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y (2021).

Hartgrink, H., Jansen, E., van Grieken, N. & van de Velde, C. Gastric cancer. LANCET 374, 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60617-6 (2009).

Siegel, R., Naishadham, D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA-A CANCER J. Clin. 62, 10–29. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20138 (2012).

Songun, I., Putter, H., Kranenbarg, E., Sasako, M. & van de Velde, C. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. LANCET Oncol. 11, 439–449 (2010).

Shen, L. et al. Management of gastric cancer in asia: resource-stratified guidelines. LANCET Oncol. 14, E535–E547 (2013).

Van Cutsem, E. et al. HER2 screening data from toga: targeting HER2 in gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Gastric Cancer. 18, 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0402-y (2015).

Kang, Y. K. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390, 2461–2471. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31827-5 (2017).

Suzuki, S. et al. Surgically treated gastric cancer in japan: 2011 annual report of the National clinical database gastric cancer registry. Gastric Cancer 24, 545–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-021-01178-5 (2021).

Kanda, M. et al. Amido-bridged nucleic acid-modified antisense oligonucleotides targeting SYT13 to treat peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. Mol. Therapy Nucleic Acids 22, 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2020.10.001 (2020).

Kanda, M. et al. Therapeutic monoclonal antibody targeting of neuronal pentraxin receptor to control metastasis in gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01251-0 (2020).

Jiang, L. X., Gong, X. M., Liao, W. D., Lv, N. H. & Yan, R. W. Molecular targeted treatment and drug delivery system for gastric cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 147, 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03520-x (2021).

Wang, Z., Meng, F. H. & Zhong, Z. Y. Emerging targeted drug delivery strategies toward ovarian cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.113969 (2021).

Wilke, H. et al. Ramucirumab plus Paclitaxel versus placebo plus Paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15, 1224–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70420-6 (2014).

Janjigian, Y. et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 398, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2 (2021).

Vandamme, M. et al. Antitumor effect of plasma treatment on U87 glioma xenografts: preliminary results. Plasma Processes Polym. 7, 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.200900080 (2010).

Fridman, G. et al. Applied plasma medicine. Plasma Processes Polym. 5, 503–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.200700154 (2008).

Tanaka, H. et al. Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma activates lactate in Ringer’s solution for anti-tumor effects. Sci. Rep. 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36282 (2016).

Kajiyama, H. et al. Perspective of strategic plasma therapy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: A short review of plasma in cancer treatment. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 53. https://doi.org/10.7567/jjap.53.05fa05 (2014).

Hattori, N. et al. Effectiveness of plasma treatment on pancreatic cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 47, 1655–1662. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2015.3149 (2015).

Torii, K. et al. Effectiveness of plasma treatment on gastric cancer cells. Gastric Cancer. 18, 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0395-6 (2015).

Tanaka, H. et al. Plasma medical science for Cancer therapy: toward Cancer therapy using nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 42, 3760–3764. https://doi.org/10.1109/tps.2014.2353659 (2014).

Iseki, S. et al. Selective killing of ovarian cancer cells through induction of apoptosis by nonequilibrium atmospheric pressure plasma. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3694928 (2012).

Utsumi, F. et al. Effect of indirect nonequilibrium atmospheric pressure plasma on anti-proliferative activity against chronic chemo-resistant ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081576 (2013).

Nakamura, K. et al. Preclinical verification of the efficacy and safety of aqueous plasma for ovarian cancer therapy. Cancers 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13051141 (2021).

Takeda, S. et al. Intraperitoneal administration of plasma-activated medium: proposal of a novel treatment option for peritoneal metastasis from gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 24, 1188–1194. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5759-1 (2017).

Sato, Y. et al. Effect of plasma-activated lactated ringer’s solution on pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-6239-y (2018).

Miron, C. et al. Cancer-specific cytotoxicity of ringer’s acetate solution irradiated by cold atmospheric pressure plasma. Free Radic. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2023.2201390 (2023).

Kim, G. J., Kim, W., Kim, K. T. & Lee, J. K. DNA damage and mitochondria dysfunction in cell apoptosis induced by nonthermal air plasma. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3292206 (2010).

Ma, Y. H. et al. Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma preferentially induces apoptosis in p53-mutated cancer cells by activating ROS stress-response pathways. PLoS ONE 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091947 (2014).

Vermes, I., Haanen, C., Steffens-Nakken, H. & Reutelingsperger, C. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods. 184, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i (1995).

Ma, R. N. et al. An evaluation of anti-oxidative protection for cells against atmospheric pressure cold plasma treatment. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3693165 (2012).

Sato, T., Yokoyama, M. & Johkura, K. A key inactivation factor of HeLa cell viability by a plasma flow. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 44. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/44/37/372001 (2011).

Ninomiya, K. et al. Evaluation of extra- and intracellular OH radical generation, cancer cell injury, and apoptosis induced by a non-thermal atmospheric-pressure plasma jet. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 46. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/46/42/425401 (2013).

Sasaki, S., Kanzaki, M. & Kaneko, T. Calcium influx through TRP channels induced by short-lived reactive species in plasma-irradiated solution. Sci. Rep. 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25728 (2016).

Kurake, N. et al. Cell survival of glioblastoma grown in medium containing hydrogen peroxide and/or nitrite, or in plasma-activated medium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 605, 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2016.01.011 (2016).

Tanaka, H. et al. Low temperature plasma irradiation products of sodium lactate solution that induce cell death on U251SP glioblastoma cells were identified. Sci. Rep. 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98020-w (2021).

Koul, H. K., Pal, M. & Koul, S. Role of p38 MAP kinase signal transduction in solid tumors. Genes Cancer. 4, 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947601913507951 (2013).

Akter, M., Jangra, A., Choi, S., Choi, E. & Han, I. Non-Thermal atmospheric pressure Bio-Compatible plasma stimulates apoptosis via p38/MAPK mechanism in U87 malignant glioblastoma. Cancers 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010245 (2020).

Matsushita, M., Nakamura, T., Moriizumi, H., Miki, H. & Takekawa, M. Stress-responsive MTK1 SAPKKK serves as a redox sensor that mediates delayed and sustained activation of SAPKs by oxidative stress. Sci. Adv. 6. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay9778 (2020).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in Gastrointestinal cancer. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-019-0115-0 (2019).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48, 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.244 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK and HT made substantial contributions to study conception and design. YI made substantial contributions to data acquisition. YI wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MK, HT, KN, MM, MH, HK, and YK made substantial contributions to manuscript revision; all authors reviewed and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary Material 2

Supplementary Material 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, Y., Kanda, M., Tanaka, H. et al. Antitumor effects of plasma-activated sodium acetate solution on gastric cancer cells. Sci Rep 15, 19807 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04977-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04977-3