Abstract

In this study, environmental DNA was used to assess marine diversity across the southern part of Okinawa Island, Japan, located in the subtropics. Diversity analysis was performed for prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Differences in diversity were detected between the west side of Okinawa (an area exposed to groundwater influenced by land-derived loads) and the east side (an area where coral reefs, beaches, and seagrass beds coexist). In particular, the community composition of prokaryotes, for which 16S rRNA metabarcoding analysis was performed, differed markedly between the east and west sides of the island. Differences in the composition of eukaryotic communities between the east and west coasts are relatively unclear, likely due to the fact that 18S rRNA metabarcoding targets a wide range of species (including almost all eukaryotic taxonomic groups), making it difficult to identify differences. On the other hand, MiFish analysis indicated that distributions of various fish species differed markedly between the east and west coasts of the island, suggesting a close relationship between differences in the coastal environment and the habitat selection by fish. We show that prokaryotic communities can be evaluated using eDNA analysis in order to monitor extensive geographic environments via water cycles. This can then be used to promote understanding of geographic variations of marine community structures of eukaryotes, including fish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coastal areas of tropical and subtropical regions are important habitats for marine organisms1,2. Their ecosystem services, such as food and tourism, are supported by this high biodiversity. However, because coastal areas are close to land, they are vulnerable to human impacts3, and how to conserve coastal ecosystems in light of these impacts has become an urgent global issue4. Okinawa Island is located in the subtropical zone, almost in the center of the Ryukyu Islands, and provides various habitats, including coral reefs, seagrass beds, tidal flats, and rocky reefs. As a result, this coastal environment also supports great biological diversity. However, Okinawa is an area of concern due to degradation of the environment caused by human activity5,6,7, and it is also a high priority for marine conservation worldwide1. Okinawa has a lot of land use around the coastal area8, and the southern part of the island in particular has a high population density and is an area where forests, human settlements, and agricultural activities coexist.

The Ryukyu Group (Ryukyu limestone) of the Quaternary Period (from about 2.6 million years ago to the present) is widely distributed in southern Okinawa Island, and because limestone allows water to pass through it easily, most rainfall seeps into the ground and flows out to the coast. Assessment of groundwater quality in Okinawa is important not only in regard to water supply, but also from the perspective of preserving biodiversity in coastal ecosystems such as coral reefs9. Southwestern Okinawa Island is agriculturally developed, with underground dams supplying water, but concerns about nitrogen from fertilizers and agricultural activities persist, and their impact on coastal ecosystems remains largely unknown10,11,12. On the other hand, the eastern region of southern Okinawa Island has a developed fringing reef with a large lagoon, and there are also relatively long natural sandy beaches and seagrass beds. Therefore, it is possible to conduct a biodiversity assessment of coastal southern Okinawa on a relatively small geographical scale, with the west coast being more susceptible to land-based loads and the east coast having a more natural landscape.

In recent years, environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding, which analyzes biota based upon environmental samples, has gained attention as a method for assessing biodiversity. eDNA metabarcoding has been studied particularly in fish13,14. It has been applied to aquatic ecosystems in the tropics and subtropics, where species diversity is extremely high15,16,17, and it has been implemented in a coral reef lagoon in northern Okinawa18, but there have been no case studies in southern Okinawa. In addition, eDNA metabarcoding can be used to understand biodiversity at various levels, including prokaryotes, by changing primers, but there are even fewer examples of biodiversity assessment in tropical and subtropical regions at multiple taxonomic levels19. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no biodiversity assessments have made along the southern Okinawa coast.

In this study, we sampled eDNA along a wide expanse of that coast, and compared biodiversity between the west side of Okinawa, which is susceptible to terrestrial load, and the east side, where coral reefs, sandy beaches, and seagrass beds exist. In this eDNA analysis, we used universal primers to simultaneously assess diversity of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and we discuss the impact that terrestrial load can have on biodiversity in tropical and subtropical coastal areas. In particular, we show that the community composition of prokaryotes, which is sensitive to environmental change20,21, differs in southwestern and southeastern Okinawa Island. With different groundwater loads, these sites can function as an environmental barometer. We show that simultaneous community analysis of taxa at different levels promotes biodiversity assessment using eDNA.

Results

Prokaryotic community structure based on 16SrRNA metabarcoding

In the molecular experiment targeting the 16S rRNA region of prokaryotes, 291 taxa were identified at the L7 (species) level of QIIME2 analysis, with Bacteroidetes bacteroidia and Alphaproteobacteria being the main groups (Fig. 1). Results of molecular experiments targeting the 18S rRNA region of eukaryotes showed that 682 taxa were identified at the L7 (species) level of QIIME2 analysis, with algae such as Dinophyceae of the Dinoflagellata, Ulvophyceae of the Chlorophyta, and Bacillariophyceae of the Diatomea being the main groups (Fig. 2). Intramacronucleata were also found in large numbers. A total of 227 species were identified through MiFish amplicon sequencing, with Planiliza macrolepis being particularly common on the east side (Fig. 3).

In the analysis using the ASV table of 16S rRNA metabarcoding (genetic data of CWOK007 were not obtained, and after dilution and filtering, CWOK004, CWOK005, and CWOK017 were excluded because there were fewer than 500 reads). A significant difference was observed in the Shannon–Weaver index (Welch’s t-test, p < 0.01) and diversity was significantly higher on the west side (Fig. 4). The maximum silhouette value was 6, but the pattern of the silhouette value plot (Fig. S1) and results of the hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. S2) showed that the main cluster consisted of three components, divided into a large cluster on the east side and a large cluster on the west side comprising two sub-clusters (Fig. 4). In the non-hierarchical cluster analysis, which was conducted with two clusters, Group 1 was assigned mainly to the west side, and Group 2 was assigned to the east side (Table S3). In the indicator species analysis, Alteromonadaceae, etc. were extracted as the main western group, and uncultured marine microorganisms of the family Cryomorphaceae were extracted as the main eastern group (Table S4). In PERMANOVA, communities also differed significantly between the west and east coasts (Table S5).

Eukaryotic community structure based on 18SrRNA metabarcoding

In the analysis using the ASV table of 18S rRNA metabarcoding, the diversity index did not differ between the west and east coasts (Fig. 5). In the nMDS plot, there was a tendency for the two clusters to be loosely separated, although they were intermingled when using a two-cluster setting (Fig. 5). The maximum silhouette value was 14 (Fig. S3), and hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. S4) showed that the community was divided into two main clusters, one on each coast. However, in the non-hierarchical cluster analysis with two clusters, there was no clear tendency to assign the two groups to the west and east sides, respectively. In PERMANOVA, the communities differed significantly between the west and east sides (Table S6).

Fish community structure based on metabarcoding using MiFish primers

In the analysis using the MiFish ASV table for metabarcoding, the diversity index did not clearly differentiate between the west and east sides (Fig. 6). The nMDS plot yielded two distinct clusters (Fig. 6). The maximum silhouette value was 2 (Fig. S5), and results of the hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. S6) showed that the sites were divided into a large cluster on each coast. In the non-hierarchical cluster analysis with two clusters, group 1 was assigned mainly to the west side and group 2 to the east side (Table S7). In the indicator species analysis conducted with two clusters, Mugil cephalus and Acanthopagrus sivicolus were detected in the main eastern group, and a relatively large number of indicator species were detected in the main western group (Table S8). In PERMANOVA, communities also differed significantly on the west and east coasts (Table S9).

Discussion

Understanding coastal biodiversity is important for predicting current and future human impacts on marine ecosystems, and maintenance of biodiversity is becoming increasingly urgent22. This study surveyed a coastal distance < 20 km, but it encompassed tropical landscapes such as coral reefs, beaches, and seagrass beds. The influence of freshwater outflow differs between east and west, so it is thought that selection due to environmental differences is especially important in formation and maintenance of communities23,24,25. The composition of prokaryotic communities is strongly influenced by environmental factors such as syntopic animals and plants, and seawater temperature and composition26. Composition of prokaryotic communities along the Okinawa coast has been influenced by urbanization27,28. Prokaryotes that inhabit sediments vary depending on the landscape, such as the seafloor, seagrass beds and coral-rich environments around Okinawa Island29.

The prokaryotic community was divided into two main groups in the southern part of Okinawa Island, due to different groundwater loads between the west and east sides. There are two underground dams in the western part of southern Okinawa Island, the Komesu underground dam and the Giiza underground dam, which were built to prevent seawater from rising inland, so as to secure water for agricultural use30,31. It has been reported that water from such underground dams may affect the coastal area through groundwater32. In addition, the community structure of prokaryotes is sensitive to environmental pollution, and nutrients loading, particularly nitrates, increases prokaryotic diversity33,34,35. Diversity of prokaryotes along the west coast is thought to be enhanced by the influx of prokaryotes from pollution sources, the reduction of dominant species due to environmental instability, and opportunistic increases of rare species34. In fact, the western region of southern Okinawa Island is reported to have a deteriorating groundwater environment, with NO3-N concentrations exceeding Japan’s environmental water quality standards in some places12. This pollution may have contributed to differences in prokaryotic community composition that we observed between the west and east coasts of southern Okinawa. In a preliminary survey, the prokaryotic community of groundwater in southwestern Okinawa tended to be more similar to that of the South China Sea than the Pacific Ocean (unpublished), suggesting that freshwater inflow from land to coastal areas can significantly affect the composition of coastal prokaryotic communities. Prokaryotic diversity was significantly higher in the west. Chariton et al.36 reported that taxonomic richness derived from eDNA was consistently high in human-influenced estuaries. On the other hand, there were no significant differences in diversity between the east and west for eukaryotes and fish. The high diversity seen in prokaryotes in areas with high levels of human influence may reflect greater prokaryote sensitivity to environmental changes20,21. Another factor that may differentiate the western and eastern regions is the influence of the open ocean. The western region faces the open ocean and is directly affected by the Kuroshio Current, while the eastern region is surrounded by reef edges and is less affected by the Kuroshio Current. It has been reported that bacterial diversity in offshore areas tends to be higher than in coastal areas37, and the high bacterial diversity along western region may reflect the inflow of seawater from offshore areas.

Although the main environmental factors that divide Okinawan prokaryotic communities into western and eastern groups are unknown, we hypothesized that the environment has changed significantly, and investigated whether eukaryotic and specifically, fish communities differ between the western and eastern sides. Amplicon-based eDNA metabarcoding was carried out using PCR, so there is a tendency for bias in taxa depending on primers used. The nuclear 18S rRNA region can be amplified by PCR for a relatively large number of taxa, and has also been used in eDNA research on Okinawa Island3. Therefore, in the present study, various taxa were detected in metabarcoding analysis of the 18S rRNA region, and complex community structure was also indicated by cluster analysis. The marine ciliate, Strombidium, was found in large numbers at eastern sites. Strombidium inhabits tidal pools, and obtains chloroplasts from macroalgae, especially Ulvophyceae, which it uses for photosynthesis38. Uncultured marine Strombidium was only detected along the east coast of Okinawa (CWOK 019–23), and Ulvophyceae was identified more frequently along the east coast. Ulva sp. was also detected at western sites, but the overall number of reads was higher along the east coast. Cymopolia vanbosseae and Bryopsis plumosa were only detected in the east. Although there are no reports of Strombidium in the Ryukyu Islands this study suggests that the distributions of Strombidium, Cymopolia vanbosseae, and Bryopsis plumosa are linked.

Fish species differed between the east and west coasts. Planiliza macrolepis was observed along the east coast, and the indicator species analysis detected Mugil cephalus and Acanthopagrus sivicolus on the east. These are estuarine fish, and the influence of the Yuuhi River near CWOK013 (Minatogawa) may be significant. There are no rivers on the east side, but there are some places where surface water flows on the beach, so the influence of this fresh water may also be seen. In addition, the west side is dominated by fish species that live in tidal pools, likely due to the fringing reef along the island. Eviota smaragdus, extracted through indicator species analysis, is a species typically found in moats along the coast of Okinawa39, and Enneapterygius philippinus is also a fish species found in tidal pools40. Given that the western side has many moats and tidal pools, occurrence of these species is consistent with this environmental condition. As such, there appears to be a close relationship between differences in coastal environments and habitat selection by fish. The fish fauna is also an excellent indicator of the coastal environment that are easily affected by underground dams.

In this study, we performed a comprehensive diversity assessment of a subtropical coastal ecosystem, including the degree of human activity through underground dams. Although the survey period was short and the extent of terrestrial loading may vary depending on precipitation, eDNA metabarcoding made it possible to survey diversity without seasonality. eDNA analysis can reveal local environmental variation by simultaneously assessing prokaryotic communities in addition to eukaryotic communities, including fish and other organisms that are the focus of environmental DNA analysis. Data obtained in this study can be compared with those from other regions, e.g., the natural, northern part of Okinawa Island, and are useful for evaluating biodiversity and human impacts in southern Okinawa Island. Furthermore, continuous environmental monitoring using methods employed in this study is expected to sensitively detect changes in coastal ecosystems in southern Okinawa Island and to contribute to ecosystem conservation by providing important baseline data. However, we need to be careful about differences in the sensitivity of detecting taxonomic groups due to differences in primers. For example, MiFish does not necessarily detect all fish species. This survey was conducted during the winter, when biological activity is relatively low, but by conducting similar surveys in different seasons in the future, it is hoped that the impact of terrestrial load on coastal ecosystems can be clarified.

Materials and methods

Sampling sites

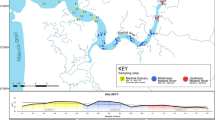

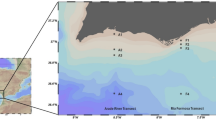

Over three days in January 2020, we selected 24 sites along the southern coast of Okinawa Island (Fig. 7, Table S1) and collected water samples. These 24 sites were divided into ‘East’ (14 sites) and ‘West’ (10 sites) regions based on the location of the underground dam. Water was collected from the sea surface using a bucket with a rope attached. Multiple buckets were thrown in, with 100 mL filtered through Sterivex filters (0.45 um) each time, up to a maximum of 1 L at each site. When collecting water, we followed standard eDNA protocols41, including DNA decontamination using hypochlorous acid. In particular, to prevent contamination between sites, we thoroughly cleaned the bucket with hypochlorous acid during our movements between sites.

Molecular experiment

Extraction of DNA from Sterivex filters was carried out using DNeasy® Blood &Tissue kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), taking care to avoid contamination by wearing lab gloves, disinfecting with sanitizers, and working on a clean bench, and by using methods described in the eDNA experimental protocol by Minamoto et al.41. For prokaryotes, the V3–V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using forward and reverse primers (P341 F-P805R42) with adapter sequences for the sequencing platform. For eukaryotes, the variable region of the 18S rRNA gene was amplified using forward and reverse primers with adapter sequences (F04-R22 mod43). For fish, we used the frequently used universal primers13, and mixed each forward primer (Mifish-U-F, Mifish-E–F) or reverse primer (Mifish-U-R, Mifish-E-R) at 10 uM and used MiFish-U/E–F or MiFish-U/E-R primers for amplification. PCR amplification and library preparation were performed using the same procedure as in Iguchi et al.44 and Maeda et al.45. We used triplicate PCR amplicons for amplicon sequencing. Sequencing was performed using a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA), and for acquisition of sequences in the 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA regions, paired-end sequencing (2 × 300 bp). For MiFish sequence acquisition, we performed paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the MiSeq Reagent Nano Kit V2 (Illumina). Raw data from these assays was submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ), and can be referenced using accession numbers DRA019327 (analysis using 16S rRNA), DRA019326 (analysis using 18S rRNA), and DRA019328 (analysis using MiFish). Basic information about sequences from each site is summarized in Table S2.

Bioinformatics

For 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA sequences, FASTQ files obtained from the above experiments were analyzed using the QIIME2 platform46. Low-quality reads were excluded, and chimeric reads were identified and removed using ‘dada2’47. Obtained amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were annotated based on a match with the reference database SILVA (silva-132–99-nb-classifier.qza48). For fish sequences, we used the MiFish pipeline49,50 with default settings to identify fish groups from paired-end sequences.

We used the ASV matrix obtained from QIIME2 and the matrix data for each taxon obtained from MiFish, and processed them in R51. For the 16S rRNA ASV matrix, Eukaryota, Mitochondria, Chloroplast, and Unassigned were removed. For the 18S rRNA ASVs matrix, Archaea, Mitochondria, Bacteria, and Unassigned were removed. The vegan package (v. 2.6.4)52 was used to apply coverage-based rarefaction to the number of reads per ASV using rrarefy function53. ASVs with a frequency < 0.1% in each sample were deleted. After transformation, ASV matrices of MiFish, 16S rRNA, and 18S rRNA data were analyzed according to our previous eDNA study44. The ‘vegan’ package was used to calculate the diversity index (species richness; Shannon–Weaver index) for each site, and the significance of differences in mean values was confirmed using the Welch t-test for west and east. Using the ASV matrices above, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the correlation coefficient and Ward’s method with the software package ‘pvclust’54. Classified clusters were statistically evaluated by determining the multi-scale bootstrap probability (AU) and general bootstrap probability (bootstrap P-value: BP) with 1000 re-samplings. And we performed non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) based on the Bray–Curtis distance using the “vegan” package. We performed non-hierarchical cluster analysis using the K-medoids method in ‘cluster’ v. 2.1.355 and estimated the number of clusters using the silhouette value. The results of nMDS and non-hierarchical cluster analysis were visualized using the ‘ggplot2’ package56. We also used the indval function in the R ‘labdsv’ package57 to calculate index values that detect characteristic taxa associated with specified clusters, and performed indicator species analysis. To statistically evaluate differences in community composition between the west (CWOK001 to CWOK010) and east coasts (CWOK011 to CWOK024) with different groundwater loads, we performed a Jaccard distance and permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 9999 iterations. Abundance data for communities assessed in this study are available in the supplementary materials (Tables S10, S11, and S12).

Data availability

Raw data for these assays was submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ), and can be referenced using accession numbers DRA019327 (analysis using 16S rRNA), DRA019326 (analysis using 18S rRNA), and DRA019328 (analysis using MiFish).

References

Reimer, J. D. et al. Marine biodiversity research in the Ryukyu Islands, Japan: Current status and trends. PeerJ 7, e6532 (2019).

Dunne, A. et al. Importance of coastal vegetated habitats for tropical marine fishes in the Red Sea. Mar. Biol. 170, 90 (2023).

DiBattista, J. et al. Environmental DNA can act as a biodiversity barometer of anthropogenic pressures in coastal ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 10, 8365 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Major threats of pollution and climate change to global coastal ecosystems and enhanced management for sustainability. Environ. Pollut. 239, 670–680 (2018).

Kawahata, H., Ohta, H., Inoue, M. & Suzuki, A. Endocrine disruptor nonylphenol and bisphenol A contamination in Okinawa and Ishigaki Islands, Japan—within coral reefs and adjacent river mouths. Chemosphere 55, 1519–1527 (2004).

Imo, S., Sheikh, M., Sawano, K., Fujimura, H. & Oomori, T. Distribution and possible impacts of toxic organic pollutants on coral reef ecosystems around Okinawa Island, Japan. Pac. Sci. 62, 317–326 (2008).

Reimer, J. D. et al. Effects of causeway construction on environment and biota of subtropical tidal flats in Okinawa, Japan. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 94, 153–167 (2015).

Iguchi, A. & Hongo, C. (eds) Coral Reef Studies of Japan (Springer, 2018).

Yoshihara, N., Matsumoto, S., Machida, I. & Uchida, Y. Deciphering natural and anthropogenic effects on the groundwater chemistry of Nago City, Okinawa Island, Japan. Environ. Pollut. 318, 120917 (2023).

Hermawan, O. et al. Effective use of farmland soil samples for N and O isotopic source fingerprinting of groundwater nitrate contamination in the subsurface dammed limestone aquifer, Southern Okinawa Island, Japan. J. Hydrol. 619, 129364 (2023).

Hermawan, O. et al. Mechanism of denitrification in subsurface-dammed Ryukyu limestone aquifer, southern Okinawa Island, Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169457 (2024).

Maruyama, R. et al. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial communities and associated network of nitrogen metabolism genes in the Ryukyu limestone aquifer. Sci. Rep. 14, 4356 (2024).

Miya, M. et al. MiFish, a set of universal PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from fishes: detection of more than 230 subtropical marine species. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2, 150088 (2015).

Miya, M. Environmental DNA metabarcoding: A novel method for biodiversity monitoring of marine fish communities. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 14, 161–185 (2022).

Alexander, J. et al. Development of a multi-assay approach for monitoring coral diversity using eDNA metabarcoding. Coral Reefs 39, 159–171 (2020).

Andriyono, S., Alam, M. J. & Kim, H.-W. Environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: Diversity study around the Pondok Dadap fish landing station, Malang, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 20, 3772–3781 (2019).

Komyakova, V., Munday, P. & Jones, G. Relative importance of coral cover, habitat complexity and diversity in determining the structure of reef fish communities. PLoS ONE 8, e83178 (2013).

Oka, S. I. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding for biodiversity monitoring of a highly diverse tropical fish community in a coral reef lagoon: Estimation of species richness and detection of habitat segregation. Environ. DNA 3, 55–69 (2021).

Stat, M. et al. Ecosystem biomonitoring with eDNA: metabarcoding across the tree of life in a tropical marine environment. Sci. Rep. 7, 12240 (2017).

Martiny, J. et al. Investigating the eco-evolutionary response of microbiomes to environmental change. Ecol. Lett. 26, S81–S90 (2023).

McLellan, S., Fisher, J. & Newton, R. The microbiome of urban waters. Int. Microbiol. 18, 141–149 (2015).

Richardson, K. et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh2458 (2023).

Palmer, T. A., Montagna, P. A., Pollack, J. B., Kalke, R. D. & DeYoe, H. R. The role of freshwater inflow in lagoons, rivers, and bays. Hydrobiologia 667, 49–67 (2011).

Palmer, T. A. et al. Determining the effects of freshwater inflow on benthic macrofauna in the Caloosahatchee Estuary, Florida. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 12, 529–539 (2016).

Dorado, S. et al. Towards an understanding of the interactions between freshwater inflows and phytoplankton communities in subtropical estuaries. PLoS ONE 10, e0130931 (2015).

Raes, J. & Bork, P. Molecular eco-systems biology: Towards an understanding of community function. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 693–699 (2008).

Ares, Á. et al. Extreme storms cause rapid but short-lived shifts in nearshore subtropical bacterial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 4571–4588 (2020).

Mars, B. M., Dudley, K., Yonashiro, Y., Mitarai, S. & Ares, A. Urbanization of a subtropical island (Okinawa, Japan) alters physicochemical characteristics and disrupts microbial community dynamics in nearshore ecosystems. Estuaries Coasts 47, 1266–1281 (2024).

Hamamoto, K. et al. Diversity, composition and potential roles of sedimentary microbial communities in different coastal substrates around subtropical Okinawa Island, Japan. Environ. Microbiome 19, 54 (2024).

Nawa, N. & Miyazaki, K. The analysis of saltwater intrusion through Komesu underground dam and water quality management for salinity. Paddy Water Environ. 7, 71–82 (2009).

Yoshimoto, S., Tsuchihara, T., Ishida, S. & Imaizumi, M. Development of a numerical model for nitrates in groundwater in the reservoir area of the Komesu subsurface dam, Okinawa, Japan. Environ. Earth Sci. 70, 2061–2077 (2013).

Ke, S., Chen, J. & Zheng, X. Influence of the subsurface physical barrier on nitrate contamination and seawater intrusion in an unconfined aquifer. Environ. Pollut. 284, 117528 (2021).

Chen, J., McIlroy, S., Archana, A., Baker, D. & Panagiotou, G. A pollution gradient contributes to the taxonomic, functional, and resistome diversity of microbial communities in marine sediments. Microbiome 7, 104 (2019).

Lo, L. et al. How elevated nitrogen load affects bacterial community structure and nitrogen cycling services in coastal water. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1062029 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Different response of bacterial community to the changes of nutrients and pollutants in sediments from an urban river network. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 14, 1–12 (2020).

Chariton, A. et al. Metabarcoding of benthic eukaryote communities predicts the ecological condition of estuaries. Environ. Pollut. 203, 165–174 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Variation in structure and functional diversity of surface bacterioplankton communities in the Eastern East China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12, 69 (2024).

McManus, G., Zhang, H. & Lin, S. Marine planktonic ciliates that prey on macroalgae and enslave their chloroplasts. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 308–313 (2004).

Hanahara, N. Cryptic diversity of Eviota (Teleostei: Gobiidae) and their habitat use in the shallow waters of Okinawa Island. Mar. Biodiv. 53, 61 (2023).

Chiang, M. C. & Chen, I. S. Taxonomic review and molecular phylogeny of the triplefin genus Enneapterygius (Teleostei: Tripterygiidae) from Taiwan, with descriptions of two new species. Raffles Bull. Zool. Supplement 19, 183–201 (2008).

Minamoto, T. et al. An illustrated manual for environmental DNA research: Water sampling guidelines and experimental protocols. Environ. DNA 3, 8–13 (2021).

Takahashi, S. et al. Development of a prokaryotic universal primer for simultaneous analysis of Bacteria and Archaea using next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE 9, e105592 (2014).

Sinniger, F. et al. Worldwide analysis of sedimentary DNA reveals major gaps in taxonomic knowledge of deep-sea benthos. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 92 (2016).

Iguchi, A. et al. Utilizing environmental DNA and imaging to study the deep-sea fish community of Takuyo-Daigo Seamount. npj Biodivers. 3(1), 14 (2024).

Maeda, A. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding of foraminifera for biological monitoring of bottom water and sediments on the Takuyo-Daigo Seamount in the northwestern Pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1243713 (2024).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Callahan, B. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Pruesse, E. et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 7188–7196 (2007).

Iwasaki, W. et al. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: A mitochondrial genome database of fish with an accurate and automatic annotation pipeline. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2531–2540 (2013).

Sato, Y., Miya, M., Fukunaga, T., Sado, T. & Iwasaki, W. MitoFish and MiFish pipeline: A mitochondrial genome database of fish with an analysis pipeline for environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1553–1555 (2018).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6–4 (2022).

Chao, A. & Jost, L. Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology 93, 2533–2547 (2012).

Suzuki, R. & Shimodaira, H. Pvclust: An R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 22, 1540–1542 (2006).

Maechler, M., Rousseeuw, P., Struyf, A., Hubert, M. & Hornik, K. cluster: Cluster analysis basics and extensions. R Package Ver. 2(1), 3 (2022).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag, 2016).

Roberts, D.W. Package ‘labdsv’. http://r.meteo.uni.wroc.pl/web/packages/labdsv/labdsv.pdf (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Steven D. Aird for editing the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (grant no. JPMEERF20194007) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of Japan, KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid (grant nos. 20H00653, 23K11518, 23KJ2204, 23KJ2206, 23H00529 and 24H00784) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and by the Research Laboratory on Environmentally Conscious Developments and Technologies (E-code) of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG, KH, KK, AS, NA, NY, and AI supervised the project. AI and MM carried out the sample collection. KG and MN carried out the experiments. KG, KH, KK, HK, and AI analyzed the data. KG and AI wrote the main manuscript. All authors commented and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gibu, K., Hamamoto, K., Koeda, K. et al. Environmental DNA analysis at multiple taxonomic levels highlights geographic variation in subtropical coastal marine communities. Sci Rep 15, 20791 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05106-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05106-w