Abstract

Pig instance segmentation is a critical component of smart pig farming, serving as the basis for advanced applications such as health monitoring and weight estimation. However, existing methods typically rely on large volumes of precisely labeled mask data, which are both difficult and costly to obtain, thereby limiting their scalability in real-world farming environments. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a novel approach that leverages simpler box annotations as supervisory information to train a pig instance segmentation network. In contrast to traditional methods, which depend on expensive mask annotations, our approach adopts a weakly supervised learning paradigm that reduces annotation cost. Specifically, we enhance the loss function of an existing weakly supervised instance segmentation model to better align with the requirements of pig instance segmentation. We conduct extensive experiments to compare the performance of the proposed method that only uses box annotations, with that of five fully supervised models requiring mask annotations and two weakly supervised baselines. Experimental results demonstrate that our method outperforms all existing weakly supervised approaches and three out of five fully supervised models. Moreover, compared with fully supervised methods, our approach exhibits only a 3% performance gap in mask prediction. Given that annotating a box takes merely 26 seconds, whereas annotating a mask requires 94 seconds, this minor accuracy trade-off is practically negligible. These findings highlight the value of employing box annotations for pig instance segmentation, offering a more cost-effective and scalable alternative without compromising performance. Our work not only advances the field of pig instance segmentation but also provides a viable pathway to deploy smart farming technologies in resource-limited settings, thereby contributing to more efficient and sustainable agricultural practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force in diverse sectors of modern production, including industry, services, and agriculture. In agriculture, AI technologies have notably enhanced crop management1,2, facilitated plant disease detection3, and improved practices in animal husbandry. The integration of AI algorithms in these domains demonstrates the potential to revolutionize traditional workflows, thereby driving both increased productivity and sustainability. Specifically, AI applications in pig farming have attracted considerable attention, resulting in numerous advancements such pig instance segmentation4,5, pig face recognition6, pig behavior recognition7, pig tracking8, pig weight estimation9, and pig health monitoring10. By leveraging AI technologies, pig farming has realized significant benefits, including enhanced precision, reduced labor costs, and improved decision-making processes, ultimately contributing to higher yields and more efficient resource management.

Among the diverse applications, pig instance segmentation stands out as one of the most fundamental tasks. Its primary objective is to accurately identify and delineate each pig within a predicted mask, particularly when multiple pigs are confined within a narrow pen. This capability is critical for higher-level applications, such as pig behavior recognition, weight estimation, and health monitoring, as it provides unique identification for each pig. Consequently, pig instance segmentation has received extensive attention, leading to the development of various innovative approaches, including advanced model architecture for superior performance11,12 and solutions addressing occlusions challenges4,5,13,14. While achieving high-precision instance segmentation results and handling severe occlusion challenges are critical objectives, existing research has often overlooked a major issue: the difficulty in obtaining high-quality labeled data. Deep learning models for instance segmentation typically require large, well-annotated datasets, but producing such datasets is both expensive and labor-intensive. Despite the progress in creating public instance segmentation datasets, specialized fields like smart pig farming still have limited publicly available data. Moreover, pixel-level mask annotation is notably more challenging than other forms of annotation, such as bounding box, edge, and scratch annotations. This is because mask annotation is a pixel-level task, whereas the others operate at the object level. As reported by Liu et al.15, annotating a single image in the widely recognized Cityscapes dataset16 required an average of more than 1.5 hours of dense labeling. In large-scale farming contexts, particularly for small research teams, the labor involved in pixel-level annotation can be overwhelming. Unlike the natural images found in many public datasets, images used for pig instance segmentation often contain numerous pigs, as the camera’s field of view often covers the entire pig pen. This results in a high density of pigs within a confined space, leading to significant occlusions. Consequently, an important concern arises: Can simpler, less time-consuming, and less labor-intensive types of annotations be used as substitutes for pixel-level annotations? As illustrated in Fig.1, mask annotation requires meticulously drawing a mask that precisely overlaps with each pig, whereas bounding box annotation only requires enclosing each pig in a rectangle. In practice, we have done a time test of annotation where one student performs mask annotation and bounidng box annotation on the same 50 images, respectively. The result shows that the average time of mask annotation is 94 seconds while the counterpart of bounding box annotation is only 26 seconds. Based on Fig.1 and our annotation test, it is evident that bounding box annotation is both simpler and faster compared to mask annotation.

In light of these observations, this paper attempts to reduce the reliance on costly mask annotations by adopting a weakly supervised learning paradigm. By leveraging less detailed annotations, bounding boxes instead of pixel-perfect masks, weakly supervised learning significantly reduces the annotation burden while maintaining performance comparable to conventional fully supervised methods. To this end, we develop a weakly supervised instance segmentation method specifically tailored for the pig farming domain, where the state-of-the-art weakly supervised model, BoxTeacher, originally proposed by Chen et al.17, is adapted as our primary framework due to its end-to-end training capability and strong performance. A key technique in BoxTeacher lies in the design of its loss functions, which include detection loss, box-supervised loss, and mask-supervised loss. The original BoxTeacher was trained on public datasets such as COCO (with 80 categories) and PASCAL VOC 2012 (with 20 categories), where its loss functions are geared toward multi-category classification. However, in pig instance segmentation, only a single category is involved. Therefore, to better align BoxTeacher with our specific task, we simplify its box-supervised and mask-supervised loss functions for binary classification. Our experimental results indicate that these simplified losses yield improved performance.

To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first to employ bounding box annotations as the primary ground truth for weakly supervised pig instance segmentation. To evaluate its effectiveness, we conduct a series of experiments in which the commonly used instance segmentation models, Mask R-CNN18, YOLACT19, SOLO20, SOLOv221 and CondInst22, are trained with mask annotations, while the proposed method and two related works, BoxInst23 and DiscoBox24 are trained solely with bounding box annotations. Our weakly supervised model achieves an Average Precision (AP) of 89.22% for bounding box prediction and 85.29% for mask prediction. In terms of box detection, our method outperforms fully supervised Mask R-CNN (85.41%) by 3.18%, YOLACT (80.61%) by 8.61%, and CondInst (86.22%) by 3%. It also surpasses the weakly supervised methods DiscoBox (81.41%) by 7.81% and BoxInst (85.36%) by 3.86%. Regarding mask prediction, only two fully supervised methods, SOLOv2 (88.51%) and CondInst (86.22%), exceed our performance. The best model, SOLOv2, achieves 88.51% AP, which is 3.22% higher than ours, whereas CondInst surpasses our method by only 1.03%. Our approach still notably outperforms Mask R-CNN (82.11%), YOLACT (82.60%), SOLO (83.41%), BoxInst (81.54%), and DiscoBox (73.42%). Although our method does not achieve the highest mask prediction performance, it offers several advantages. First, it demonstrates a relatively small performance gap (at most 3%) compared to fully supervised methods such as SOLOv2 and CondInst. Second, considering that mask annotation requires 94 seconds per image, whereas bounding box annotation requires only 26 seconds, the substantial reduction in annotation time cost far outweighs the slight performance loss. As a result, our method provides a cost-effective and practically feasible solution for real-world applications in pig farming.

In summary, our contributions are threefold:

-

Pig instane segmentation with bounding box annotations. We demonstrate that training pig instance segmentation models solely with bounding box annotations is both feasible and effective, significantly reducing the time and labor required for mask labeling while maintaining performance comparable to fully supervised methods.

-

Bridging multiple tasks in pig health monitoring system. By integrating bounding-box annotations within a weakly supervised framework, our approach serves as a bridge between different modules in a pig health monitoring system, such as tracking models (for movement data) and weight estimation models, thereby ensuring consistent pig IDs and seamless task integration.

-

A effective method for scalable dataset expansion. We propose a practical strategy for rapidly expanding annotated datasets by generating segmentation masks from bounding boxes. Annotators only need to correct minor errors, substantially lowering annotation costs relative to manual pixel-level labeling.

Related works

Pig instance segmentation

Pig instance segmentation has attracted considerable attention due to its ability to provide unique identification for each individual pig. Numerous studies have been published in recent years. For instance, Jia et al.11 introduced a pixel self-attention module, incorporating both channel and spatial attention mechanisms into the YOLACT model19, combined with a feature pyramid module, which improved the model’s performance and transferability. Similarly, Hu et al.12 proposed an attention mechanism to guide instance segmentation models by integrating an attention module into Mask R-CNN18 and Cascade Mask R-CNN25. To address occlusion challenges in pig instance segmentation, Tu et al.13 developed the PigMS R-CNN model, based on Mask Scoring R-CNN26, and replaced the conventional Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) with a soft NMS module, thereby enhancing segmentation performance in group-pig pens. Similarly, Huang et al.4 adapted a center-clustering network to mitigate occlusions by representing each object’s center with pixels and tracking these centers to generate mask predictions. Additionally, Gan et al.14 presented a two-stage amodal instance segmentation method specifically for piglets during crushing events. In the first stage, Mask R-CNN generates initial mask predictions; in the second stage, bounding boxes derived from these masks are extended via a self-adaptive bounding box extension technique. The feature maps of bounding boxes overlapping with the sow are encoded using von Mises-Fisher distributions and then refined by a Bayesian lattice classifier to produce the final amodal instance segmentation masks. Finally, Huang et al.5 proposed a semi-supervised Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) capable of producing occlusion-free prediction masks, even when the input images contain occluded pigs.

All of the aforementioned studies emphasize designing model architectures or algorithms to improve performance and address occlusion challenges in instance segmentation. By contrast, the primary objective of this paper is to reduce labeling costs without compromising model accuracy. Specifically, we advocate the use of simpler bounding box annotations instead of the more complex and time-consuming mask annotations for training the instance segmentation model.

Weakly supervise learning in agriculture

With continuous technological advancements, the scale of agricultural operations has grown, rendering traditional labor-intensive practices increasingly impractical. Consequently, the agricultural sector has widely adopted advanced AI techniques for management. Most of these methods, however, rely on fully supervised learning, which requires large amounts of annotated data. To alleviate the high costs of data annotation, many researchers have explored weakly supervised learning approaches that demand fewer annotations. For example, Zhao et al.27 proposed a weakly supervised semantic segmentation network based on scrawl labels, consisting of a pseudo-label generation module, an encoder, and a decoder. The pseudo-label generation module converts scrawl labels into pseudo labels, thereby reducing the reliance on extensive manual annotation. Petti et al.28 employed weakly supervised techniques for a cotton-counting task, using multiple-instance learning to train their model and active learning to iteratively expand the dataset. Chen et al.29 introduced a weakly supervised disease segmentation method for drone imagery, integrating an auxiliary branch module and a feature-reuse module to segment diseased regions in crops under image-level labeling constraints. Wang et al.30 applied weakly supervised learning to UAV forest fire imagery, employing a self-supervised attention-based foreground-aware pooling mechanism and a context-aware loss function to generate high-quality pseudo labels in lieu of manual annotations.

Clearly, weakly supervised learning has been widely adopted in agriculture, demonstrating promising results. Unlike the above-mentioned studies, however, this work applies weakly supervised learning to the task of pig instance segmentation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such application in pig instance segmentation. Our study thereby offers a valuable example of how weakly supervised learning can be effectively employed in this domain.

Materials and methods

Data collection

The data used in this study were collected from a pig farm at Soonchunhyang University, South Korea. Multiple cameras were strategically installed at different viewpoints, capturing images against various backgrounds and operating continuously both day and night. Fig. 2 provides sample images from these cameras, illustrating the diversity and generalizability of our dataset. We employed the open-source tool CVAT (https://www.cvat.ai/) for image annotation. The dataset includes only one category, and the annotation format follows the COCO standard31. In total, our dataset comprises 13,383 images containing 130,743 pigs, which are split into training, validation, and test datasets in an 8:1:1 ratio. Detailed statistics of the dataset are presented in Table 1. All images are annotated with both bounding boxes and masks to facilitate performance comparisons with fully supervised models that require mask supervision. However, during the training of the weakly supervised model, only bounding box annotations are utilized. The mask annotations in the validation and test datasets are reserved solely for evaluating model performance.

Method

Our method builds upon the state-of-the-art weakly supervised approach, BoxTeacher17, with modifications to the loss functions to better suit our specific task. The architecture of our method is depicted in Fig.3.

The main framework of our method. The left sub-figure is the paradigm of weakly supervised instance segmentation, and the right one is the specific architecture of CondInst model22.

It comprises two CondInst models22, denoted as \(\varvec{f}_1\) and \(\varvec{f}_2\) respectively. Although both models share the same structure, they differ in their parameter-update mechanisms. A key component of this approach is the box-based mask assignment, which matches the predicted masks \(\textbf{M}^p\) to the ground-truth bounding boxes \(\textbf{B}^g\). The matched masks are subsequently treated as pseudo masks \(\textbf{M}^g\), serving as ground truth for training the model \(\varvec{f}_2\). Unlike prior methods that rely on a two-step training strategy, our design enables end-to-end training. Specifically, the parameters of model \(\varvec{f}_2\) are optimized via standard gradient descent, while the parameters of model \(\varvec{f}_1\) are updated using an Exponential Moving Average (EMA) mechanism, as shown in Eq.1.

Here, \(\varvec{f}_1\) and \(\varvec{f}_2\) denote the parameters of the two models, respectively. The coefficient \(\alpha\) is an empirically determined value, typically set to 0.999, based on the work of He et al.32.

Pig instance segmentation

The instance segmentation model used in our method is derived from CondInst22. Compared to the earlier Mask R-CNN model, CondInst eliminates the need for Region of Interest (ROI) operations and instead leverages a fully convolutional network, resulting in faster inference and improved performance. As illustrated on the right side of Fig. 3, the input image is first processed by a backbone network, often ResNet-50 or its variants to extract feature maps. These feature maps are then passed through Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs), producing multi-scale outputs. Finally, K mask heads take these multi-scale features as input, generating predictions that include masks, bounding boxes, and confidence scores.

A key innovation of the CondInst model lies in its approach to instance representation. Unlike Mask R-CNN, which relies on bounding boxes to represent instances, CondInst encodes the concept of an instance into the parameters of its mask heads. These parameters are dynamically generated and optimized via backpropagation, offering greater flexibility in representing irregular shapes that bounding boxes alone cannot capture. The object detector within the CondInst model is based on FCOS33, whose simplicity and adaptability remove the need for ROI operations and facilitate the integration of FPNs. This design enables the model to fully leverage multi-scale feature maps, thereby improving its ability to handle diverse and complex shapes–a critical advantage for pig instance segmentation, where object shapes can be highly irregular.

Box-mask matching

The goal of the box-mask matching process is to provide pseudo-label information for the segmentation model \(\varvec{f}_2\). Algorithm.1 details the procedure for assigning predicted masks to ground-truth (GT) bounding boxes in a one-to-one fashion, using both confidence scores and Intersection over Union (IoU) as criteria. Formally, the algorithm takes the following inputs:(1) a set of predicted bounding boxes \(\textbf{B}^p\), predicted masks \(\textbf{M}^p\), and corresponding confidence scores \(\textbf{C}^p\); (2) a set of GT bounding boxes \(\textbf{B}^g\) and their total number K; (3) two threshold values: a confidence threshold \(\tau _{c}\) and an IoU threshold \(\tau _{iou}\). The algorithm systematically filters and sorts the predictions, then iterates through them in descending order of confidence to identify the best-matching GT box. First, the pseudo masks \(\textbf{M}^g\) are initialized to zero, and an index array A of length K is set to -1, indicating that no GT box has been assigned a pseudo mask yet. Next, any predicted bounding boxes with confidence scores below \(\tau _{c}\) are removed. The remaining boxes are then sorted in descending order of confidence, yielding an index list S.

For each prediction i in the sorted list S, two variables are initialized: \(u_{i} \leftarrow -1\) (representing the current maximum IoU found for prediction i) and \(v_{i} \leftarrow -1\) (representing the GT box index that achieves the best match). The algorithm then iterates over all GT boxes \(\textbf{B}^g\) from 1 to K. If a GT box j has already been assigned to a different prediction (i.e., \(A_{j}>0\)), that GT box is skipped. Otherwise, the IoU value \(IoU_{ij}\) is computed according to Eq.2.

If \(IoU_{ij}\) exceeds \(\tau _{iou}\) and is higher than the current best IoU \(u_{i}\), the algorithm updates \(u_{i} \leftarrow IoU_{ij}\) and \(v_{i} \leftarrow j\). After all GT boxes have been scanned, if \(v_{i} > 0\), indicating a suitable match, the predicted mask \(\textbf{M}^p_{i}\) is assigned to GT box \(v_{i}\) by setting \(\textbf{M}^g_{\,v_{i}} \leftarrow \textbf{M}^p_{\,i}\). The index array A is also updated as \(A_{v_{i}} \leftarrow i\), indicating that prediction i is now assigned to GT box \(v_{i}\).

By processing predictions in descending order of confidence, the algorithm ensures that higher-confidence predictions are prioritized in obtaining their best available GT match. Consequently, each GT box is assigned at most one predicted mask, with the top IoU candidate being chosen among predictions exceeding the confidence threshold \(\tau _{c}\).

Loss functions

Our proposed method optimizes the model in an end-to-end manner using only box annotations, and the overall loss function comprises three components: the detection loss \(\textbf{L}_{det}\), the box-supervised loss \(\textbf{L}_{box}\), and the mask-supervised loss \(\textbf{L}_{mask}\). Notably, only model \(\varvec{f}_2\) is directly optimized via gradient descent, while the supervision for the mask-supervised loss is derived from model \(\varvec{f}_1\). The total loss function is expressed as follows:

The detection loss \(\textbf{L}_{det}\) includes two parts: object classification and bounding box regression. The classification component employs a focal loss, given by \(\textbf{L}_{focal}(p) = -\alpha (1-p)^{\gamma }\log (p)\), where \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) are hyperparameters, and p is the predicted probability. Bounding box regression is optimized using an IoU loss, analogous to Eq.2. Thus, the detection loss is formulated as Eq.4,

Here, \(p_{x,y}\) denotes the predicted probability at pixel (x, y) since the model produces dense predictions for each pixel. The term \(\textbf{B}_{x,y}\) corresponds to the bounding box associated with pixel (x, y), and \(\mathbbm {1}_{\{c^*_{x, y} > 0\}}\) is an indicator function based on the class label \(c^*_{x, y}\). This indicator function ensures that the IoU loss is computed only for foreground objects. \(N_{pos}\) represents the number of positive samples. In the original BoxTeacher loss functions, \(c^*_{x, y}\) can take multiple values (e.g., 80 categories in the COCO dataset). In our task, however, there are only two possible classes: 1 for the pig (positive) and 0 for the background (negative). Accordingly, we simplify the loss functions by restricting \(c^*_{x, y} \in \{0, 1\}\).

The box-supervised loss \(\textbf{L}_{box}\) aims to address two key aspects: ensuring that the predicted mask remains within the corresponding ground-truth bounding box and refining pixel-level classification inside the bounding box (accounting for background pixels). To achieve these goals, we propose two loss terms that focus on pixel coordinate alignment and color disparity, respectively. Formally, let \(\textbf{M}^p \in (0,1)\) be the predicted mask and \(\textbf{B}^g\) be its matched bounding box. To ensure the mask is contained within \(\textbf{B}^g\), we apply a projection-based loss involving the Dice loss \(\textbf{L}_{Dice}\)34 as shown in Eq.5.

Here, \(\max _y\) and \(\max _x\) denote maximum operations along the y-axis and x-axis, respectively. For color disparity, we define a neighborhood region by a \(K \times K\) kernel (e.g., \(3\times 3\)). Let \(y_e \in (0,1)\) denote the label of an edge e connecting two pixels: the center pixel of the kernel (i, j) and one of its neighboring pixels (l, k). If \(y_e=1\), it indicates that (i, j) and (l, k) share the same ground-truth label. We compute \(P(y_e=1)\) by Eq.6, and set \(P(y_e=0)=1-P(y_e=1)\).

This binary classification is iteratively performed on all pixels inside the bounding box, and the color disparity loss is defined in Eq.7, where N is the number of edges.

Combining these two terms, the overall box-supervised loss is \(\textbf{L}_{box}=\textbf{L}_{proj} + \textbf{L}_{color}\).

The mask-supervised loss is relatively straightforward. Since the predicted masks from model \(\varvec{f}_1\) are treated as pseudo masks \(\textbf{M}^g \in (0,1)\), we directly compare them with the output masks \(\textbf{M}^p \in (0,1)\) of model \(\varvec{f}_2\) using Dice loss. The corresponding loss function is given by Eq.8,

where \(N_{pse}\) denotes the number of pseudo masks.

Experiments

Experiment setup

The dataset used in our experiments is described in the Data Collection section. Briefly, the training set comprises 10,701 images containing 108,045 pigs, the validation dataset includes 1,341 images with 11,763 pigs, and the test dataset consists of 1,341 images with 12,222 pigs. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed method, we also evaluate five fully supervised models using mask annotations. In contrast, for the weakly supervised models, only bounding box annotations serve as ground truth. During testing, only the model \(\varvec{f}_2\) is used to generate predictions.

Our method is implemented in PyTorch35, and both segmentation models shown in Fig.3 build on the CondInst framework. Unless otherwise specified, the CondInst model employs ResNet-50 as its backbone, and we initialize the training parameters with pre-trained CondInst weights from the COCO dataset. Image augmentations applied during training include random horizontal flipping, random resizing, color jittering at a probability of 0.8, grayscale conversion at a probability of 0.2, and Gaussian blurring at a probability of 0.5. In the box-mask matching process, the confidence threshold \(\tau _c\) and IoU threshold \(\tau _{iou}\) are both set to 0.5. The focal loss hyperparameters \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) are set to 0.25 and 2.0, respectively, and a \(3\times 3\) kernel size is used for the color disparity loss. The training procedure spans 36,000 iterations, with the first 1,000 iterations dedicated to learning rate warm-up (warm-up factor = 0.0001). The base learning rate is 0.04, with a batch size of 4. After 24,000 iterations, the learning rate is decreased by a factor of 10 every 4,000 iterations. We use the SGD optimizer with a weight decay of 0.00005. All experiments are conducted on two NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPUs.

Evaluation metrics

The evaluation metrics used in this study are derived from the standard COCO-style metrics31, specifically the Average Precision, i.e., AP at IoU thresholds of 0.5 and 0.75. Additionally, we include the AP for large objects as an additional metric. AP is computed as the area under the precision-recall curve by integrating precision values across different levels of recall. Precision, recall, and AP are formally defined as Eq.9,

where TP, FP, and FN denote the number of true positives (correct classifications), false positives (incorrect classifications), and false negatives (missed detections), respectively.

Experimental results

Table 2 presents the performance of the proposed method on the pig instance segmentation task and provides a comparison with other existing methods. Fig. 4 provide several examples of visualization on instance segmentation. The performance comparison is divided into two categories. On the one hand, the compared methods include five fully supervised models trained with mask annotations, Mask R-CNN18, CondInst22, YOLACT19, SOLO20, and SOLOv221. On the other hand, we also compare our method with two related weakly supervised models, BoxInst23 and DiscoBox24.

Comparison with fully supervised models

From Table 2, it is apparent that the proposed method outperforms the Mask R-CNN model in both box detection and mask segmentation, achieving 89.22% AP in box detection (a 3.81% improvement) and 85.29% AP in mask segmentation (a 3.18% increase over Mask R-CNN). Although our method uses the CondInst model as its base architecture with only box annotations for training, it achieves performance comparable to that of CondInst trained with mask annotations. Notably, it surpasses CondInst by 3% AP in box detection, and while it lags by 1.03% AP in mask segmentation, it performs better at higher IoU thresholds (e.g., \(\textrm{AP}_{0.5}\) and \(\textrm{AP}_{0.75}\)). This result can be attributed to the mutual optimization process between the two CondInst models in our approach. Both models are initialized with pre-trained weights from the COCO dataset, enabling effective leverage of prior knowledge. Model \(\varvec{f}_1\) generates pseudo masks of reasonable quality for training model \(\varvec{f}_2\). Subsequently, \(\varvec{f}_1\) updates its parameters using those of \(\varvec{f}_2\) via an EMA mechanism, creating a cycle of mutual interaction and optimization that exceeds what a single model can achieve. These findings underscore that using box annotations to train pig instance segmentation models is not only feasible but also substantially reduces labeling costs.

We also compare our method with other popular models, YOLACT, SOLO, and SOLOv2, all of which use mask annotations. YOLACT attains 80.61% AP in box detection and 82.60% AP in mask segmentation, both below our results. SOLO achieves 83.41% AP in mask segmentation, which is still lower than ours. Meanwhile, SOLOv2 reports 88.51% AP in mask segmentation, surpassing our overall AP of 85.29%. However, at certain IoU thresholds (\(\textrm{AP}_{0.5}\) and \(\textrm{AP}_{0.75}\)), our method achieves higher or comparable scores (98.32% and 96.69%, respectively) compared to SOLOv2 (96.72% and 95.60%). Although our approach shows a slight performance gap in mask segmentation relative to SOLOv2 and CondInst, this difference is small when weighed against the considerable time saved by using box annotations instead of mask annotations. Therefore, balancing labeling cost and model performance suggests that box-only supervision is both feasible and practically significant for real-world pig farming applications.

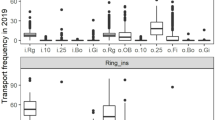

To further assess the performance of Mask R-CNN, CondInst, BoxInst, and our model, we visualize their results on the validation dataset at different stages of the training process. As shown in Fig. 5, our method consistently attains the best box detection performance, while CondInst achieves the top results in mask segmentation, with our method coming in second. An unexpected observation is that the weakly supervised BoxInst model delivers performance comparable to Mask R-CNN. Specifically, as shown in Fig.5, BoxInst continuously exceeds Mask R-CNN in box detection, and toward the later stages of training, both models exhibit nearly identical detection performance. In mask segmentation, BoxInst initially performs better but slightly underperforms Mask R-CNN in later stages, likely due to overfitting in BoxInst. Analyzing their test dataset results confirms their overall closeness: BoxInst trails Mask R-CNN by only 0.05% AP in box detection and 0.57% AP in mask segmentation. Notably, BoxInst outperforms Mask R-CNN in \(\textrm{AP}_{0.5}\) and \(\textrm{AP}_{0.75}\). These findings further highlight the feasibility and potential of using bounding boxes as supervisory information for pig instance segmentation tasks.

Ablation studies

Effectiveness of modified loss functions

The original loss functions in Boxteacher are designed for multi-categories instance segmentation task, and a complicated noise-aware pseudo mask loss is employed, considering the multiple categories and noisy backgrounds. While in our pig instance segmentation, there is only one category. Thus, we simplify the original loss functions to be adapted for our task. Specifically, in the detection loss \(\textbf{L}_{det}\), we restrict the class label in the indicator function to two values: 0 and 1. And for the mask-supervised loss \(\textbf{L}_{mask}\), we directly use the Dice loss to compare the predicted mask and pseudo mask. The performance comparisons of these two kinds of loss functions are shown in Table 3.

From Table 3, it can be seen that the model employing the revised loss functions achieves improvements across all metrics. Notably, the mask AP increases by 2.63%. Despite being simpler than the original loss functions, the revised ones yield better performance. This is likely because pig instance segmentation involves only a single class, and overly complex loss functions may confuse the model, leading to incorrect predictions. These experimental results underscore the importance of modifying the loss functions for this specific task.

Comparisons on different backbones

Deploying algorithms in practical applications often encounters the challenge of limited computational resources. In our supporting project fundings, we frequently need to run these algorithms on edge computing devices such as the Jetson Nano. Consequently, finding an optimal balance between performance and computational requirements is crucial. In this subsection, we investigate the impact of three different backbone networks on models \(\varvec{f}_1\) and \(\varvec{f}_2\). Specifically, “ResNet-R50” denotes ResNet with 50 convolutional layers, “ResNet-R101” refers to ResNet with 101 layers (which has more parameters than ResNet-R50), and “ResNet-R101 DCN” further replaces standard convolutions with deformable convolutions, resulting in the largest parameter count among the three. Table 4 presents performance statistics, and Fig. 6 offers direct visual comparisons.

The experimental results show that using ResNet-R101 DCN as the backbone yields the highest performance for box detection, achieving an overall AP of 89.81% and the best \(\textrm{AP}_{0.5}\) (98.30%) and \(\textrm{AP}_{0.75}\) (95.81%). However, for mask segmentation, the ResNet-R101 backbone attains the highest AP at 85.51%, while ResNet-R101 DCN still leads in \(\textrm{AP}_{0.5}\) (98.36%) and \(\textrm{AP}_{0.75}\) (96.22%). Despite these slight differences, the overall performance gap among the three backbones is less than 1% in AP for both tasks. Fig. 6 further illustrates that their performance metrics are closely aligned, suggesting that the choice of backbone has a relatively minor effect on instance segmentation outcomes. Additionally, as depicted by the training loss curves in Fig. 7, all three models converge to similar loss values, with ResNet-R101 DCN showing a marginally lower loss throughout training–indicating a slight optimization advantage. These findings imply that increasing the depth of the backbone, as in ResNet-R101 and ResNet-R101 DCN, provides only negligible improvements in segmentation performance while substantially raising computational costs. Accordingly, considering the trade-off between efficiency and accuracy, we select ResNet-R50 as the backbone for our proposed method. This choice strikes a balance between performance and computational overhead, making the algorithm more suitable for deployment on edge computing devices such as the Jetson Nano, where resources are often limited. Consequently, the method is particularly well-suited for real-world applications that demand efficient processing under constrained hardware conditions.

Discussion

Advantages of the proposed method

The proposed weakly supervised learning method, which uses box annotations as ground truth, provides three key advantages over fully supervised methods that rely on mask annotations. First, the time and labor required for box annotation are significantly lower than those for mask annotation. Mask annotation necessitates time-consuming, pixel-level labeling, leading to a substantial workload, particularly for large-scale pig datasets. In contrast, box annotation only requires drawing a rectangular box for each pig, greatly reducing both complexity and annotation time. This simpler approach allows even non-experts to annotate data more rapidly, thus accelerating the data preparation process. Moreover, precise pixel-level annotation is prone to subjective bias and labeling errors. Box annotation, being simpler and less subjective, can mitigate these errors, especially when combined with a weakly supervised instance segmentation model, thereby enhancing model robustness and generalizability. Second, weakly supervised models using box annotations can achieve performance comparable to fully supervised models, and in some cases even surpass them. This finding suggests that weakly supervised instance segmentation models are a highly viable alternative in engineering applications for smart pig farming, particularly in resource-constrained scenarios. Finally, because box annotations are straightforward to generate, they enable the rapid creation of large-scale annotated datasets. This scalability makes it feasible to train large models tailored to smart pig farming, such as ViT-based models, which can further advance performance and application breadth.

Application prospect

The proposed method holds practical applicability in three major domains. First, it can serve as a viable substitute for fully supervised models commonly used in pig instance segmentation tasks. Because it relies on simpler and more quickly generated bounding box annotations, this approach allows researchers to rapidly conduct experiments and achieve accurate pig instance segmentation models without incurring the high time and labor costs associated with mask annotation. Second, the proposed method can effectively bridge multiple high-level tasks within a pig health monitoring system. In such systems, various indicators, such as distance traveled (derived from tracking models) and weight changes (estimated through weight prediction models), are often combined to assess the health status of pigs. Tracking models typically output detection boxes along with tracking IDs, while weight estimation models frequently require instance segmentation masks to calculate weight changes. By accepting detection boxes from the tracking model as input and generating the necessary segmentation masks, the proposed method ensures that each pig’s ID remains consistent across these two tasks. This unified ID assignment avoids issues where a pig’s tracking ID may otherwise become difficult to match with its instance segmentation ID. Finally, the proposed method can be employed as an automatic annotation algorithm, thereby facilitating large-scale data labeling. In particular, bounding box annotations can first be used to train the instance segmentation model. This trained model can then generate segmentation masks for extensive datasets. Annotators merely need to correct erroneous mask labels, which requires significantly less effort than annotating masks from scratch. Consequently, the proposed method can substantially reduce the time and labor involved in producing large-scale annotated datasets for subsequent model training and evaluation.

Limitations and future work

Training a pig instance segmentation model using box annotations as ground truth is an innovative approach, and the experimental results demonstrate promising performance. However, like any method, the proposed approach still faces certain limitations that may be difficult to overcome in specific scenarios. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the model tends to overlook targets with indistinct color or texture features, resulting in missed detections. This issue arises either because the model fails to generate a pseudo-mask for these targets, thus preventing subsequent matching and loss calculation, or because the generated pseudo mask has a low confidence score and is filtered out during the matching process. One potential solution to this problem is to use targeted data augmentation strategies that enhance image texture features, thereby enabling the model to generate pseudo-masks with higher confidence. In addition, in highly occluded regions, the model is prone to producing imprecise segmentation boundaries, leading to over-segmentation. We attribute this behavior to overlapping box annotations and the similar coloration of different targets, which hinders the model’s ability to distinguish them. A possible remedy might involve employing multi-scale kernels in the box-supervised loss function to refine loss computation in such complex scenarios.

In future work, we will continue to address these limitations with the aim of further improving the accuracy of our weakly supervised instance segmentation model. Moreover, drawing inspiration from recent advances in multi-modal large models in computer vision, we plan to explore the potential of using natural language as a supervisory signal for pig instance segmentation. Natural language supervision can be more annotation-efficient than box-based methods, potentially providing a valuable alternative for large-scale, real-world applications.

Conclusion

This paper presents a weakly supervised method for pig instance segmentation that utilizes bounding box annotations rather than mask annotations, thereby reducing labeling workload. The use of bounding boxes significantly lowers annotation costs while still delivering robust instance segmentation performance. To tailor the approach specifically for pig instance segmentation, we refined the loss function of an existing weakly supervised model. Experimental results confirm the effectiveness of weakly supervised learning with box labels: our method outperforms the commonly used fully supervised models such as Mask R-CNN, trained with mask annotations and achieves performance comparable to the more advanced fully supervised CondInst model. These findings underscore the feasibility of using bounding box annotations in instance segmentation tasks and highlight the promise of weakly supervised techniques in the pig farming domain. In future work, we plan to explore the potential of natural language supervision as an alternative approach for training pig instance segmentation models.

Data availability

The dataset used in this paper was collected and labeled by our team. The dataset is available upon reasonable request by contacting Heng Zhou via email at hengz@jbnu.ac.kr.

References

Tong, S., Zhang, J., Li, W., Wang, Y. & Kang, F. An image-based system for locating pruning points in apple trees using instance segmentation and rgb-d images. Biosystems Engineering. 236, 277–286 (2023).

Zheng, C. et al. A mango picking vision algorithm on instance segmentation and key point detection from rgb images in an open orchard. Biosystems engineering. 206, 32–54 (2021).

Dong, J. et al. Data-centric annotation analysis for plant disease detection: Strategy, consistency, and performance. Frontiers in Plant Science. 13, 1037655 (2022).

Huang, E. et al. Occlusion-resistant instance segmentation of piglets in farrowing pens using center clustering network. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 210, 107950 (2023).

Huang, E. et al. A semi-supervised generative adversarial network for amodal instance segmentation of piglets in farrowing pens. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 209, 107839 (2023).

Yan, H. et al. Study on the influence of pca pre-treatment on pig face identification with random forest. Animals. 13, 1555 (2023).

Xu, J., Ye, J., Zhou, S. & Xu, A. Automatic quantification and assessment of grouped pig movement using the xgboost and yolov5s models. Biosystems Engineering. 230, 145–158 (2023).

Zhou, H., Chung, S., Kakar, J. K., Kim, S. C. & Kim, H. Pig movement estimation by integrating optical flow with a multi-object tracking model. Sensors. 23, 9499 (2023).

Nguyen, A. H. et al. Towards rapid weight assessment of finishing pigs using a handheld, mobile rgb-d camera. biosystems engineering. 226, 155–168 (2023).

Racewicz, P. et al. Welfare health and productivity in commercial pig herds. Animals. 11, 1176 (2021).

Jia, Z. et al. Pixel self-attention guided real-time instance segmentation for group raised pigs. Animals. 13, 3591 (2023).

Hu, Z., Yang, H. & Yan, H. Attention-guided instance segmentation for group-raised pigs. Animals. 13, 2181 (2023).

Tu, S., Yuan, W., Liang, Y., Wang, F. & Wan, H. Automatic detection and segmentation for group-housed pigs based on pigms r-cnn. Sensors. 21, 3251 (2021).

Gan, H. et al. Peeking into the unseen: Occlusion-resistant segmentation for preweaning piglets under crushing events. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 219, 108683 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Leveraging instance-, image-and dataset-level information for weakly supervised instance segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 44, 1415–1428 (2020).

Cordts, M. et al. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3213–3223 (2016).

Cheng, T., Wang, X., Chen, S., Zhang, Q. & Liu, W. Boxteacher: Exploring high-quality pseudo labels for weakly supervised instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 3145–3154 (2023).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P. & Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2961–2969 (2017).

Bolya, D., Zhou, C., Xiao, F. & Lee, Y. J. Yolact++ better real-time instance segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 44, 1108–1121 (2022).

Wang, X., Kong, T., Shen, C., Jiang, Y. & Li, L. Solo: Segmenting objects by locations. In Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T. & Frahm, J.-M. (eds.) Computer Vision – ECCV 2020, 649–665 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020).

Wang, X., Zhang, R., Kong, T., Li, L. & Shen, C. Solov2: Dynamic and fast instance segmentation. In Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M. & Lin, H. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 17721–17732 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2020).

Tian, Z., Shen, C. & Chen, H. Conditional convolutions for instance segmentation. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 16, 282–298 (Springer, 2020).

Tian, Z., Shen, C., Wang, X. & Chen, H. Boxinst: High-performance instance segmentation with box annotations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 5443–5452 (2021).

Lan, S. et al. Discobox: Weakly supervised instance segmentation and semantic correspondence from box supervision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 3406–3416 (2021).

Cai, Z. & Vasconcelos, N. Cascade r-cnn: High quality object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 43, 1483–1498 (2019).

Huang, Z., Huang, L., Gong, Y., Huang, C. & Wang, X. Mask scoring r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 6409–6418 (2019).

Zhao, L., Zhao, Y., Liu, T. & Deng, H. A weakly supervised semantic segmentation model of maize seedlings and weed images based on scrawl labels. Sensors 23, 9846 (2023).

Petti, D. & Li, C. Weakly-supervised learning to automatically count cotton flowers from aerial imagery. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 194, 106734 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. A weakly supervised approach for disease segmentation of maize northern leaf blight from uav images. Drones 7, 173 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Weakly supervised forest fire segmentation in uav imagery based on foreground-aware pooling and context-aware loss. Remote Sensing. 15, 3606 (2023).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13, 740–755 (Springer, 2014).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 9726–9735, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00975 (IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2020).

Tian, Z., Shen, C., Chen, H. & He, T. Fcos: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (2019).

Milletari, F., Navab, N. & Ahmadi, S.-A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In 2016 fourth international conference on 3D vision (3DV), 565–571 (Ieee, 2016).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2019-NR040079), and by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through the Agri-Bioindustry Technology Development Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (RS-2025-02307882).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Heng Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Experiments, Writing – original draft, revisions. Jiuqing Dong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Experiments. Shujie Han: Conceptualization, Experiments. Seyeon Chung: Data curation, Data labeling. Hassan Ali: Experiment analysis. Sangcheol Kim: Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This study exclusively involved the collection of behavioral data from pigs at the Soonchunhyang University pig farm using non-invasive video recording. No physiological or invasive experiments were conducted on the animals. Therefore, no ethical issues related to animal experiments are applicable to this research. All procedures and data handling complied with relevant laws, guidelines, and institutional policies. During data collection, we adhered to all applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines and regulations. The data collection process was limited to non-intrusive video monitoring of pig behavior and did not involve any physiological manipulation or intervention.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Dong, J., Han, S. et al. Weakly supervised learning through box annotations for pig instance segmentation. Sci Rep 15, 19706 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05113-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05113-x