Abstract

During high-intensity mining of shallow coal seams, severe overburden movement and surface subsidence can lead to geological hazards like ground fissures. This study investigates these phenomena at a representative working face in the Shendong mining area. Numerical simulations were conducted to analyze overburden displacement, stress distribution, fracture evolution, breakage characteristics, and surface subsidence under varying mining advance distances. A theoretical model of overburden breakage and surface subsidence was developed, revealing the key mechanisms involved. Results indicate that overburden breakage and collapse occur in distinct stages. The presence of key strata is essential for maintaining the rock layer stability and controlling surface subsidence. Initial roof breakage occurs at an advance distance of 80 m, with periodic intervals of 40 to 60 m. Stress distribution evolves through three stages: overall pressure relief, single-peak stress concentration, and double-peak stress concentration. Fractures propagate through the overburden, ultimately reaching the key strata and surface. Once the key strata are fractured, a “voussoir arch” structure suppresses further fracture expansion. The theoretical model and simulations align closely with field data, providing a scientific basis and technical support for controlling subsidence and facilitating surface ecological restoration during high-intensity mining.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal mining plays a crucial role in China’s energy infrastructure and has significantly contributed to the socioeconomic development of the country over the past few decades. However, coal resource exploitation has profoundly and extensively impacted the ecological environment. During most coal mining operations, the overburden above the goaf undergoes uncontrolled collapse, resulting in the movement, deformation, and destruction of the rock layers from the coal seam to the surface. These layers are categorized into three zones: the caving zone, the fracture zone, and the bending subsidence zone. In areas with shallow coal seams, only the caving and fracture zones may develop1,2. Fractures formed in these zones can lead to secondary issues, including water inrush, gas outbursts, and damage to the surface environment3,4,5,6. In the ecologically fragile Shendong mining area, high-intensity mining of shallow, thick coal seams has caused severe damage to the surface environment. This includes depletion of water resources, frequent geological disasters, vegetation degradation, and soil erosion, all of which seriously threaten the ecological security of the mining region. The unique geological conditions of the Shangwan Mine in the Shendong area, characterized by shallow and highly variable coal seam burial depths, exacerbate these issues7,8. Mining-induced subsidence exhibits distinctive discontinuous damage characteristics, such as stepped collapse and dense ground fissures, which amplify ecological damage and complicate restoration efforts. These challenges significantly hinder ecological conservation and the high-quality regional development.

Previous research on overburden breakage and surface damage caused by coal mining has primarily concentrated on overburden movement, fracture formation, surface deformation, and the development of ground fissures. Studies utilizing field analyses and simulations have dynamically analyzed variations in surface damage caused by high-intensity mining of shallow, thick coal seams. Based on these analyses, principles for road alignment and slope stabilization under mining-induced dynamic conditions have been proposed9,10,11,12. Wang et al. employed physical similarity simulation experiments to investigate overburden movement and fracture development during shallow coal seam mining13,14. It was concluded that after the initial breakage of key strata, the fragmented rocks above settle synchronously until a hinge structure forms, followed by collapse. After settlement ceases, periodic fracturing of key strata results in the formation of “voussoir beam” structures. Yuan et al. utilized numerical simulations to model mining dynamics and observed that caving, fracture development, and bending subsidence zones develop during the mining of thick unconsolidated coal seams15,16. It was found that due to the lower density of the unconsolidated zones, fractures develop more prominently. The segmented compacted backfill technique was proposed as an effective method for controlling severe roof collapse and surface subsidence in goaf areas. It was suggested by Hu et al. that as mining progresses, the compaction strength of the overlying strata in the central goaf gradually increases17. Simultaneously, displacements of the immediate roof and the compacted strata above the goaf also increase, while peak stresses in the stress concentration zones on both sides decrease. This observation aligns with the findings of Wang et al., who combined numerical simulations with field measurements to reveal the pressure characteristics during mining.18. Xu et al. reported a parabolic relationship between the width-to-depth ratio of shallow coal seams and the surface subsidence coefficient, with ground fissure development exhibiting a "double-cycle + stable phase" dynamic evolution19. Li et al. noted that as the working face advances, vertical stress concentration zones shift to deeper strata, resulting in shear failure under high stress. This also results in significant settlement and tensile failure of the mining roof20. Hou Enke et al. validated the feasibility of utilizing the particle flow code (PFC) method to simulate surface discontinuous deformation and studied patterns of ground fissure development during coal seam mining21.

Although the morphological characteristics and spatial distribution patterns of ground fissures have been the primary focus of prior studies, limited attention has been given to the characteristics of overburden breakage and surface damage22,23,24,25. These gaps are particularly evident under conditions of significant coal seam thickness, shallow burial depth, and rapid mining advancement. In particular, the dynamic evolution of fracture development and surface deformation across different stratigraphic layers as the working face advances warrants further investigation. To address this gap, this study focuses on the Shendong mining area, using a typical working face as the engineering background. The characteristics of overburden displacement, stress distribution, fracture evolution, breakage patterns, and surface subsidence are investigated under varying advance distances during the high-intensity mining of shallow, thick coal seams. This research aims to provide new scientific insights into subsidence control and ecological restoration in goaf areas under these conditions. The characteristics of overburden displacement, stress distribution, fracture evolution, breakage patterns, and surface subsidence are investigated under varying advance distances during the high-intensity mining of shallow, thick coal seams. This research is aimed at providing new scientific insights into subsidence control and ecological restoration in goaf areas under these conditions.

Theoretical Model

Theoretical model of overburden breakage in shallow buried high-strength mining

Initial fracture of the immediate roof

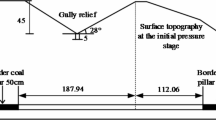

As the working face advances along the strike direction from the open-off cut, the span of the immediate roof gradually increases. When this span reaches its critical limit, the roof fractures. The span at this critical point is referred to as the initial weighting step distance. Based on the principles of elasticity, the problem of immediate roof fracture can be simplified to a plane strain problem when the working face advances to a certain distance. Before the roof fractures, the immediate roof can be modeled as a fixed-end beam26. In this model, the exposed immediate roof is supported at one end by the coal seam near the working face and at the other end by the boundary coal pillar27, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The stress components within a clamped beam under a uniformly distributed load are determined using the semi-inverse method of elasticity28. The normal stress boundary conditions at the upper and lower boundaries are as follows:

Based on the stress boundary conditions, σy = f(y) is assumed.

The stress function can be obtained as: \(\Phi ={x}^{2}f\left(y\right)+x{f}_{1}\left(y\right)+{f}_{2}\left(y\right)\) from \({\sigma }_{fx}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\Phi }{\partial {y}^{2}}\).

Substituting into the compatibility equation Δ4Φ = 0 yields:

The following results are obtained by substituting Eq. (2) into the stress component formulas \({\sigma }_{fy}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\Phi }{\partial {x}^{2}}\) and \({\tau }_{fxy}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\Phi }{\partial x\partial y}\):

The displacement component formulas are derived from the relationship between displacement and stress:

In the formulas, a, b, c, d, f, g, h, I, ω, u0, and v0 represent undetermined coefficients, while E denotes the elastic modulus. The following results are obtained based on the normal and shear stress boundary conditions (fxy)y = ± H/2 = 0:

The horizontal and vertical displacements of the clamped beam are expressed as:

The results are derived as follows:

By substituting the determined coefficients into Eqs. (3) and (4), the stress and displacement components are obtained as follows:

In these formulas, σfx, σfy, τfxy, uf0, and vf denote the horizontal stress, vertical stress, shear stress, horizontal displacement, and vertical displacement at any point within the basic roof, respectively. q is the total load on the basic roof, including the overburden and self-weight, MPa. H is the thickness of the basic roof in meters, m. 2Lf is the span of the basic roof in meters, m. μ is the Poisson’s ratio of the rock layer, and x and y are the coordinates of any point within the clamped beam. Related studies indicate that the failure mode of the rock beam is primarily tensile or shear failure29. The distribution patterns of the maximum principal stress and maximum shear stress within the rock beam determine its failure mode. The expressions for the maximum principal stress and maximum shear stress are given as follows:

According to the theory of material mechanics, the bending moment at the two fixed ends of a clamped beam is M1 = qLf2/3. After the fixed ends fracture, the support conditions at both ends change to simply supported, resulting in a bending moment at the center of the beam of M2 = qLf2/2. Since the maximum principal stress at the bottom center of the simply supported beam is typically greater than the maximum principal stress at the top ends of the clamped beam under the same thickness-to-span ratio28, it is assumed that three fracture surfaces are simultaneously generated in the beam. Based on the simplified boundary conditions, the vertical displacement at each point of the clamped beam ends can be expressed as follows in Eq. (9):

In the formula, wf represents the displacement of the clamped beam in millimeters, mm. H1 is the mining height of the working face. [wt] is the critical deflection value for fracture of the clamped beam. When n approaches 0, the clamped beam structure undergoes fracture and instability, and wfmax reaches its maximum value of H1. From Eq. (9), the vertical displacement wf at any point on the clamped rock beam can be determined. The distribution of wf is influenced by the thickness and span of the basic roof rock beam. Currently, the assumption of isotropy is treated as a first-order approximation in the research. Future studies will incorporate layered anisotropic characteristics through numerical modeling.

Periodic fracture of the immediate roof

After the initial fracture of the basic roof, periodic fractures occur as mining continues. At this stage, the clamped beam model is inapplicable. Due to the large mining height in high-extraction working faces and the implementation of the full caving method, the immediate roof collapses but does not completely fill the goaf. of the full caving method, the immediate roof collapses but cannot completely fill the goaf. When the bearing key strata are not subjected to the extrusion effects of the collapsed blocks, they can be treated as a cantilever deep beam structure30. Thus, the periodic weighting of the basic roof can be simplified into a cantilever thick beam model subject to uniform load, as illustrated in Fig. 2. uniform load31, as shown in Fig. 2.

The stress components within a cantilever beam subjected to a uniformly distributed load can be determined using the semi-inverse method of elasticity. The normal stress boundary conditions at the upper and lower boundaries are expressed as follows:

The stress boundary condition is assumed as: σsy = g(y).

The stress function can be derived as: \(\Phi ={x}^{2}g\left(y\right)+x{g}_{1}\left(y\right)+{g}_{2}\left(y\right)\) from \({\sigma }_{sx}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\Phi }{\partial {y}^{2}}\).

Substituting into the compatibility equation Δ4Φ = 0, the following result can be obtained:

The stress function Φ:

By substituting Eq. (2) into the stress component formula \({\sigma }_{sy}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\Phi }{\partial {x}^{2}}\) and \({\tau }_{sxy}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\Phi }{\partial x\partial y}\), the following result can be obtained:

The displacement component formula is:

In the formula, a, b, c, d, f, g, h, I, k, ω, u0 and v0 are undetermined coefficients, and E represents the elastic modulus. Based on the normal and shear stress boundary condition (τxy)y=±h/2 = 0, the following results can be obtained:

According to Saint Venant’s principle, the following can be obtained:

The result can be obtained as: \(h=\frac{3q{L}_{s}}{2H}\), \(i=-\frac{3q\left(10{L}_{s}^{2}-{H}^{2}\right)}{10{H}^{3}}\), \(k=0\)

The horizontal and vertical displacements of the cantilever beam are specified as follows: \({u}_{x=0,y=0}=0\), \({v}_{x=0,y=0}=0\), \({u}_{x=-{L}_{s},y=-H/2}=0\).

It follows that: \(\omega =\frac{q{L}_{s}\left(7-5\mu \right)}{2HE}\), \({v}_{0}=0\), \({u}_{0}=0\).

Substituting the determined undetermined coefficients into Eqs. (3) and (4), the stress components and displacement components are obtained as follows:

In the equation, Ls represents the span of the cyclic compression base, m; other variables are the same as those for a fixed-ended beam. According to the theory of material mechanics, the bending moment at the fixed end of the cantilever beam is given by M = qLs2/2. After the fixed end failure, the boundary condition at the fixed end changes to a simply supported condition32. Based on the simplified boundary conditions, the vertical displacement ws (where ws = vs) at any point along the fixed-supported beam is expressed by Eq. (15). However, the current computational models do not consider progressive cracking and localized plastic deformation; these factors should be incorporated in future research.

Theoretical model of surface subsidence in shallow buried high-intensity mining

The surface subsidence basin model of the gently inclined coal seam’s rectangular goaf area is utilized as the deflection function of the key stratum controlling surface movement, based on the semi-inverse method of thin plate theory to enhance the representativeness of the deflection function.

\({w}_{m}\) represents the maximum deflection of the plate in this stratum; is the dimension of the n-th rock plate in the direction of the long axis, measured from the coal seam roof upwards; is the dimension of the rock plate in the direction of the short axis; d is a parameter controlling the shape of the deflection curve along the z-axis.

The x-axis is defined as the direction of the coal seam strike, the y-axis as the dip direction, and the z-axis as the direction vertically downward from the goaf area.

\({a}_{n}\) is the dimension of the n-th rock plate in the direction of the long axis, measured upwards from the coal seam roof; \({b}_{n}\) is the dimension of the rock plate in the direction of the short axis.

The (n − 1)-th layer exerts a reaction force on the n-th layer, which can be described using the Winkler foundation reaction coefficient k33. According to the elastic surface differential equation of a Winkler elastic foundation plate:

\({q}_{0}\) is the load applied to the n-th rock layer, which includes the self-weight of the n-th layer and the weight of all the overlying rock layers; \({D}_{n}\) is the bending stiffness of the n-th rock plate; and k is the reaction coefficient of the (n − 1)-th layer on the n-th rock layer.

Near horizontal coal seam mining surface subsidence basin modeling using Winkler elastic foundation thin plate theory as34:

The applicability of the theoretical model is validated by comparing it with field-measured surface settlement data from the Shen Dong mining area35. As illustrated in Fig. 3, both theoretical and measured data indicate that surface subsidence increases rapidly before stabilizing as the working face advances. This finding demonstrates that the theoretical model effectively captures the trend of subsidence variation. However, in the vicinity of the excavation area (0–100 m), the measured subsidence is higher than the theoretical value. This discrepancy arises from a local mismatch between the model assumptions and actual engineering conditions. The theoretical model is based on the elastic foundation plate theory, while the overburden in the excavation area is influenced by mining-induced fractures and weak bedding planes, exhibiting significant plastic yielding. In the region farther from the excavation area (100–300 m), the theoretical and measured values align closely (RMSE = 38 mm), indicating that the model reliably predicts the overall bending subsidence of the overburden. This accuracy is attributed to the stress regulation effect of the key layers. The high flexural stiffness of the primary key layer effectively suppresses the upward transmission of stress, resulting in a more uniform subsidence distribution. Overall, the calculated values derived from the theoretical model exhibit high reliability, particularly in the medium to far distance regions, accurately predicting variations in subsidence in practical engineering applications.

Numerical model

Particle flow simulation principles

The Particle Flow Code (PFC) is a discrete element method (DEM) program that differs from continuum mechanics-based methods. In contrast to finite element methods that rely on mesh and grid concepts, particle flow theory links the microscopic mechanical properties of particles to their macroscopic mechanical behaviors. The macroscopic state of the system is reflected through particle interactions. Therefore, the mesh and grid concepts typically used in finite element analysis are not involved in PFC36. The movement of blocks in particle flow theory is simulated by alternating between force–displacement laws and Newton’s second law. This process enables the connection of two or more particles to form arbitrary configurations. Figure 4 illustrates the computational cycle and analysis process utilized in PFC37.

Model construction and parameter calibration

Model construction

In this study, the geological prototype of the overlying rock strata of the 12,401 working face at the Shangwan Coal Mine in the Shen Dong mining area is utilized. The working face is characterized by a shallow burial depth, large mining height, extensive area, and rapid advancement, classifying it as a typical high-intensity mining area. The average burial depth of the coal seam is 180 m, with an average thickness of 8.8 m and an actual mined thickness of 8.2 m. The length of the working face measures 300 m, and the advancement speed is 12 m/day. A two-dimensional particle flow model for mining-induced deformation is established based on the gravity similarity criterion, experimental conditions, and actual site conditions, as shown in Fig. 5. The model dimensions are 500 m × 220 m, incorporating a total of 150,100 particles are included. To simulate coal seam mining, particles corresponding to the coal seam are removed from the model.

During the simulation, horizontal lateral displacements at the left and right boundaries were constrained, while fixed support conditions were applied at the bottom. The upper boundary is set as a free boundary, with gravity (g = 9.8 m/s2) applied. Excavation commenced 120 m from the left boundary of the model, with each advancement step measuring 10 m to simulate coal seam mining along the strike. After each excavation step, equilibrium was considered reached if the average unbalanced force of the model was less than or equal to 1 × 10⁻5. A total of 13 layers of coal and rock strata were incorporated into the model.

Parameter calibration

The particle flow discrete element software PFC features two types of bonding models: the contact bonding model and the parallel bonding model. In the contact bonding model, specified normal and tangential bonding strengths are assigned between particles. However, this model can only transmit forces and not moments, which limits its ability to accurately simulate rock failure. Conversely, the parallel bonding model can be conceptualized as a series of springs with constant normal and tangential stiffness, uniformly distributed across the contact surface and centered at the contact points38. The relative motion at the contacts generates both forces and moments, thus meeting the requirements for simulating rock fracture. Therefore, the Parallel Bonded Model was selected as the constitutive model for the numerical simulation39. The correct selection of mesoscopic parameters is crucial for model construction. The mesoscopic mechanical parameters that simulate particle flow primarily include the contact modulus (\({E}_{c}\)), the ratio of normal to tangential stiffness (\(\frac{{k}_{n}}{{k}_{s}}\)), the friction coefficient, the bonding modulus (\(\overline{{E}_{c}}\)), the ratios of normal and tangential bonding stiffness (\(\frac{\overline{{k}_{n}}}{\overline{{k}_{s}}}\)), the normal bonding strength (\(\overline{\sigma }\)), and the tangential bonding strength ((\(\overline{\tau }\)). Given the numerous mesoscopic mechanical parameters involved in the parallel bonding model, the following assumptions were made during the study40,41:

-

1)

Since the macroscopic and mesoscopic friction coefficients are similar, the particle friction coefficient is set equal to the macroscopic friction coefficient.

-

2)

Considering that the specimen is a homogeneous material, the particle contact modulus is assumed to be equal to the bonding modulus, i.e., (\(\overline{\tau }\)). Additionally, the ratios of normal to tangential stiffness for the parallel bonding and contact models are set to be equal, i.e., (\(\frac{{k}_{n}}{{k}_{s}}=\frac{\overline{{k}_{n}}}{\overline{{k}_{s}}}\)).

-

3)

Given that circular particles are used in PFC, the actual cohesion of the coal body is less than that of the model, while the internal friction angle is greater than that of the model. Therefore, the mesoscopic internal friction angle and cohesion are used to replace the peak strength, with parameters equal to the macroscopic cohesion and internal friction angle.

In the PFC particle flow software, there are notable differences between mesoscopic parameters and macromechanical parameters, necessitating a scientific conversion. Initially, macromechanical parameters for each rock layer are measured through laboratory tests. Subsequently, correlation regression analysis is performed on the macro- and microscopic parameters, and empirical formulas for macro-mesoscopic conversion are used to calculate the required mesoscopic parameters for simulation. A series of empirical formulas for macro-mesoscopic parameters have been derived through extensive experiments and simulations, with the most commonly used formulas listed as follows42:

In the equations, E represents the elastic modulus (GPa), v denotes Poisson’s ratio, and the constants are defined as follows: a = 1.652, b = -0.395, c = 0.209, d = 0.111. The compressive strength is denoted as σc (MPa), while and represent the normal and tangential strengths of the parallel bonding model, respectively (MPa). The constants e = -0.965, f = 2.292, i = 1.327, and indicate the tensile strength (MPa) with h = -0.174, k = 0.463, j = 0.289.

Based on Eqs. (17) to (20), the required mechanical parameters were calculated based on the macromechanical parameters of the rock layers. Subsequently, a trial-and-error method was employed to iteratively adjust the mesoscopic mechanical parameters until the represented macromechanical parameters met the specified requirements. The mesoscopic parameters for each layer are detailed in Table 1. The model is inclined at an angle of 0°, with particle radii ranging from 0.35 to 0.6 m. The initial porosity of the generated model is established at 0.01.

Results and discussion

Breakage and migration patterns of overlying strata under high-intensity mining of shallow coal seams

In-depth research into the breakage, migration, and surface damage patterns of overlying strata during high-intensity mining of shallow coal seams is deemed essential for minimizing and controlling mining-induced damage. The breakage and migration of the overburden during high-intensity coal seam mining are directly linked to the stability of the goaf and surface subsidence. Furthermore, the collapse and fracturing of the overlying strata have a significant impact on the ventilation flow in the goaf and play a decisive role in gas migration and methane extraction. Therefore, the influence of overburden breakage and fracture development on gas flow must be investigated to optimize goaf ventilation, enhance methane extraction efficiency, and ensure mine safety.

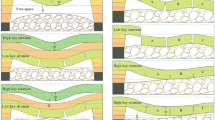

Overburden breakage and collapse

As the working face advances, the fracturing and collapse of the overburden undergo dynamic changes, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Upon reaching 53 m, the immediate roof undergoes its initial collapse. Additional collapses of the immediate roof occur as mining progresses. According to the critical layer theory proposed by Qian et al43, the 11th layer of fine-grained sandstone is identified as the first sub-critical layer. Upon reaching 80 m, the 10th layer of the basic roof begins to collapse, and by 100 m, initial fracturing of the basic roof occurs. At 120 m, the basic roof enters its initial periodic fracturing phase, accompanied by some rotation, resulting in surface subsidence. As the 10th layer of fine-grained sandstone completely collapses, the 9th layer of siltstone begins to detach before fully collapsing, while slight subsidence is observed in the 8th layer of fine-grained sandstone. This indicates that the 10th layer is the second sub-critical layer. Prior to the fracturing of the basic roof, cracks form at a certain distance ahead of the working face and gradually develop into fractures as mining progresses. At 140 m, fracturing and subsidence of the basic roof and the soft rock layers it controls continue. A distinct “masonry beam” structure begins to form between the fractured blocks of the basic roof, as illustrated in the figure. Delamination occurs between the soft rock and hard rock layers above the basic roof, which further intensifies surface subsidence. As the working face advances, significant fracturing is no longer exhibited by the 8th layer of fine-grained sandstone and the layers above it, indicating that the 8th layer serves as the primary critical layer. At 180 m, gradual subsidence of the hard rock layer above the basic roof and the soft rock layers it controls occurs, while inter-layer delamination decreases. Delamination begins to appear between the hard rock layers near the surface (the surface damage control layer) and the underlying soft rock layers. By 200 m, delamination between the various rock layers largely closes, leading to gradual subsidence from the immediate roof to the surface. At 220 m, inter-layer delamination is completely closed. At 260 m, the geological model enters a state of over-extraction, resulting in maximum observed surface subsidence.

Field measurements indicate that the initial fracturing of the basic roof occurs at approximately 60 m, and surface subsidence begins when the working face reaches approximately 100 m. The simulation results correlate well with field observations35, confirming that the simulation accurately reflects the patterns of rock fracturing and surface subsidence during coal mining.

Overburden stress and displacement

Overburden stress distribution

As shown in Fig. 7, with the gradual advancement of the working face, the stress distribution in the coal seam roof and mined-out area exhibits a three-stage evolutionary pattern closely related to the characteristics of high-intensity mining in shallow coal seams. Based on the calculations from Eq. (13) and a comparative analysis with existing research, it is evident that the stress in the mined-out area transitions from overall depressurization (53–120 m, stress < 2 MPa) to a unimodal distribution (120–180 m, peak value 3.95 MPa), and then to a bimodal structure (220–260 m, peak value 11.2 MPa). This transition is essentially a result of the dynamic load-bearing and stress transfer between the critical layer and the coal pillar. It is noteworthy that the mechanical response during the bimodal stress stage is similar to the stress field reconstruction phenomenon observed by Wang et al. in deep multi-coal seam mining44: after the fracture of the main critical layer (8# fine sandstone, depth 110 m), its load-bearing function transfers to the adjacent coal pillars, while the central compaction zone forms a secondary load-bearing structure through the compression of fragmented rock mass. This process aligns with Brady and Brown’s classic theory of coal pillar-roof collaborative load-bearing45, but this study further captures the stress oscillation phenomenon at the moment of the critical layer fracture through PFC simulations. In contrast to the static load-bearing assumption of the critical layer in previous studies, the stress redistribution in the roof under dynamic disturbances exhibits significant nonlinear characteristics.

The above mechanism suggests that in high-intensity mining of shallow coal seams, stress transfer exhibits a “bidirectional suppression” effect: the high-stress zone of the coal pillar transmits compressive force to the overlying rock layers, while surface subsidence acts on the deep rock masses through the critical layer, ultimately achieving subsidence equilibrium.

Overburden displacement variations

As the working face advances, a layered response in the distribution of overburden displacement is exhibited, which shows a lag compared to changes in stress. The displacement of the overburden, as shown in the displacement contour map in Fig. 8, is closely related to the expansion of the goaf and the breakage of the overburden, propagating gradually from the immediate roof to the critical layers and the surface. From the start of the mining operation until full extraction, overburden displacement undergoes a dynamic evolution from local subsidence to full subsidence.

When the working face reaches 53 m, the goaf is relatively small, and only the immediate roof and basic roof experience slight subsidence. The displacement of the immediate roof is approximately 100 mm, and the other layers remain largely unaffected, indicating that overburden deformation in this phase is concentrated in the immediate roof area. As the working face progresses to 80 m, the goaf expands, leading to a significant increase in subsidence of the immediate and basic roofs. The cumulative subsidence of the basic roof reaches 300 mm, while other layers begin to experience slight subsidence. However, the surface and surface damage control layers remain unaffected, and the overburden’s impact on the surface is still limited. At 100 m, the basic roof undergoes its first periodic breakage and collapse. The fractured rock blocks experience small-angle rotation, and the cumulative subsidence of the unfractured basic roof increases to 600 mm. At this point, the disturbance caused by the breakage of the basic roof intensifies, leading to an expanded subsidence range. The goaf begins to affect the surface.

By the time the working face reaches 140 m, another periodic breakage occurs in the basic roof, and the area of overlying siltstone exposure nearly doubles compared to the previous stage. The subsidence of the siltstone approaches that of the basic roof, indicating significant control of the siltstone subsidence by the basic roof. Overall, a substantial increase in subsidence occurs across all layers. At 180 m, the range of overburden subsidence expands further, and delamination between layers is almost eliminated. The overburden subsidence’s effect on the surface becomes more pronounced, with the maximum surface subsidence reaching 306 mm, signaling that overburden subsidence has reached the surface and is gradually entering a stable subsidence phase. Finally, when the working face advances to 260 m, the ratio of advancement to burial depth reaches 1.44. According to mining subsidence theory, an over-extraction state is reached by the goaf, with both overburden and surface subsidence attaining their maximum values for this geological condition. At this stage, the cumulative subsidence of the basic roof and surface reaches 4158 mm and 443 mm, respectively, closely matching field measurements.

Overburden fractures and porosity

Development of overburden fractures

As illustrated in Fig. 9, fracture range, density, and connectivity progressively increase with working face advancement, extending upward from the goaf through the overburden toward the surface. When the working face reaches 80 m, fracture development is primarily concentrated within the goaf. Horizontal delamination fractures predominantly occur between the immediate and basic roof, exhibiting low density. When the working face reaches 140 m, fractures enter a rapid expansion phase. The periodic breakage of the basic roof significantly enhances the development of vertical breakage fractures. At this stage, the breakage fractures begin to extend below the main key layer, the fracture density increases significantly, and the distribution range and connectivity of horizontal delamination fractures expand. Vertical breakage fractures near the surface begin to appear, but they are weak and have limited direct impact on the surface. At 180 m, the fracture propagation range further expands. Vertical breakage fractures penetrate the main key layer, progressively extending into overlying strata and influencing near-surface overburden. During this phase, near-surface fracture density rises substantially, vertical breakage fracture connectivity improves, and surface cracks initiate. Surface disturbance induced by the goaf becomes more pronounced. Horizontal delamination fractures primarily develop between the basic roof and main key layer, further accelerating overburden subsidence and deformation.

When the working face reaches 260 m, the goaf enters an over-extraction state, and the range of fracture development stabilizes. Vertical breakage fractures penetrate the main key layer and extend through the layers above it. The fracture density reaches its maximum below the main key layer, while the connectivity of fractures near the surface significantly increases. Horizontal delamination fractures extend slightly above the key layer, resulting in an expansion of the range and scale of surface cracks. The maximum surface subsidence reaches 443 mm.

Overburden porosity distribution patterns

The preceding fracture development analysis yielded critical insights into overburden structural changes. As shown in Fig. 10, with the advance of the working face, the distribution of porosity is gradually expanded from the goaf to the key layers and the surface. High porosity zones are mainly concentrated in the delamination range and collapse zones. When the working face reaches 53 m, the high porosity zone is concentrated within the goaf, with a maximum value ranging from 0.8 to 1.0. At this stage, vertical fractures are initially developed but have not yet connected to the key layers, and porosity in areas above the key layer remains relatively unchanged, around 0.2. By the time the working face reaches 140 m, the distribution range of porosity is significantly expanded, and the porosity density below the key layers is greatly increased. The high-stress concentration zones on both sides of the goaf further drive the formation of fractures. Porosity reaches its peak in the delamination zone, and the connectivity of fractures is significantly enhanced. When the working face reaches 180 m, the range of porosity changes extends above the key layers. Porosity near the surface layers is increased to 0.5, indicating that changes in porosity are beginning to affect the surface. At this point, the rock layers above the key layer experience overall subsidence, and the delamination zone is gradually compacted and closed. The connectivity of vertical fractures further enhances the porosity in the high porosity regions. When the working face reaches 260 m, the goaf enters an over-extraction state, and the range of porosity change is further expanded above the main key layer. Near-surface hard-rock porosity escalates to 0.7. Concurrent with surface subsidence and cracking, high-porosity connectivity propagates to the surface. Meanwhile, closed delamination zones exhibit declining porosity, whereas fracture-zone porosity stabilizes at ~ 0.6, corroborating fracture-porosity synergy.

The results indicate that during various stages of the working face advancement, porosity gradually expands from high values in the delamination zone to the caving zone, critical layers, and the surface. The 8# fine-grained sandstone of the main critical layer plays a dominant role in the synergistic evolution of roof fractures and surface damage under high flexural strength and stress conditions. As shown in Fig. 6f, when the working face advances to 180 m, the masonry beam structure formed by the fracture of the main critical layer generates a self-stabilizing arch effect above the mined-out area. The horizontal thrust component of this structure inhibits further delamination of the overlying rock layers. This also results in the development of only localized microcracks above the main critical layer, which is consistent with Yuan et al.'s findings regarding the energy barrier effect of essential layers46. This study further quantifies the relationship between the horizontal thrust component of the masonry beam and the crack suppression effect. As illustrated in Fig. 7d, after the fracture of the main critical layer, its load-bearing capacity transfers to the adjacent rock layers, which explains the migration of surface cracks toward the edges of the mined-out area. Compared to the simply supported beam model proposed by Cun et al.36, this study reveals the stress reversal characteristics before and after the fracture of the critical layer more accurately through fixed boundary conditions. This includes the transition from tensile stress zones to compressive stress zones, providing a new theoretical basis for the "critical layer-coal seam" cooperative disaster control theory in shallow coal seam mining and deepening the understanding of the chain reaction behavior of roof fractures.

Figure 11 presents the variation curves of porosity and fracture count as a function of increasing lag distance. It is evident that both porosity and fracture count show a significant upward trend with increasing lag distance, indicating a strong correlation between the two. As the lag distance increases from 53 to 260 m, porosity rises from 6.95% to 7.88%, while the number of fractures surges from 1,523 to 45,803, demonstrating an exponential growth relationship between the two. Further analysis reveals that the rate of change in porosity is 0.0035% m⁻1, while the growth rate of fracture density is 183.6 m⁻1, with a correlation coefficient reaching 0.92. This indicates that porosity serves as a quantitative representation of the connectivity of the fracture network. During the initial mining phase (53–100 m), the limited disturbance range results in only localized damage, leading to a relatively slow growth rate of both fracture count and porosity. Once the lag distance exceeds 100 m, the growth rates of fracture count and porosity accelerate significantly. This is attributed to the instability and failure of the key layer, which enhances the occurrence of widespread fracture connectivity and expansion, resulting in decreased overall integrity of the rock mass and an increase in flow pathways, causing the pore structure to loosen rapidly. Notably, the increase in fracture count far exceeds that of porosity. For instance, between 120 and 220 m, the number of fractures nearly doubles, while porosity only increases from 7.26% to 7.68%. This indicates that although the number of fractures rises significantly, many of these fractures are small and dispersed, contributing minimally to the overall volume.

Surface Damage Patterns Under High-Intensity Mining of Shallow Coal Seams

To comprehensively investigate overburden breakage, migration, and surface damage patterns during high-intensity mining of shallow coal seams at varying extraction distances, additional monitoring lines were deployed for surface damage assessment.A total of seven measurement lines were established above the coal seam, with 17 columns along the strike. The horizontal distance between displacement reference points was set at 1000 mm. Vertical spacing measured 8 m between Lines 1–6 and 10 m between Lines 6–7. Line 1 was positioned 2 m below the surface, with Column 1 situated 100 m from the model boundary. Monitoring results are presented in Fig. 12.

When the working face advanced to 80 m, subsidence was observed in all overburden layers, except the surface and the surface damage control layer. Basic roof subsidence peaked at 6098 mm, whereas other strata exhibited minimal subsidence (< 150 mm). When the working face reached 120 m, surface subsidence of 121 mm was recorded. At this point, the basic roof experienced its first periodic breakage and collapse. The broken rock blocks exhibited some rotation, although the rotation angle was small, and the subsidence continued to increase, reaching 7850 mm. The subsidence in the overlying siltstone layer reached 6100 mm, while the fine-grained sandstone layer above the basic roof showed comparatively less subsidence. Despite the working face advancing to 120 m, the angle of rock layer breakage and the hinge effect between broken rock blocks after the basic roof’s periodic collapse kept the suspended length of the overlying siltstone small, preventing significant subsidence of the fine-grained sandstone layer. When the working face advanced to 180 m, all layers continued to exhibit grouped subsidence. The subsidence of the basic roof and its overlying siltstone reached 7981 mm and 6234 mm, respectively. The layers 75.8 m, 54 m, and 33.8 m below the surface subsided by 2490 mm, 365 mm, and 342 mm, respectively. Delamination subsidence diminished relative to the 100 m advancement stage. By the time the working face reached 260 m, the subsidence of the basic roof and surface increased to 7728 mm and 557 mm, respectively, marking the transition into an over-extraction state. Surface subsidence attained its geological maximum under these conditions.

To further validate the reliability of the PFC rock layer model, a comparative analysis was conducted on the subsidence of overburden at different depths (68 m, 115 m, and 141 m) as a function of lag distance, with a detailed discussion of subsidence characteristics at varying depths. As shown in Fig. 13, the subsidence of the overburden significantly increases with depth, indicating that deeper rock masses are more sensitive to mining disturbances. At a depth of 141 m, the maximum subsidence reaches 5389.18 mm, which is approximately 3.05 times the depth factor47 at 68 m (1765.61 mm). Additionally, subsidence at all depths stabilizes after a lag distance of 150 m.

Notably, in the vicinity of the excavation area (0–50 m), the pattern observed is PFC simulated values > theoretical values > measured values. This discrepancy is primarily due to the particle flow model not accounting for stiffness degradation caused by near-field rock fracturing, which leads to an overestimation of the rate of layer separation development under dynamic disturbance48. In the region farther from the excavation area (50–200 m), the observed values exceed the theoretical values, which in turn exceed the PFC simulated values. This is primarily due to the rheological effects of weak interlayers during the compaction of the overburden (Fig. 9h), which promote continuous subsidence. The theoretical model does not incorporate a viscoplastic constitutive relationship, leading to an underestimation of long-term subsidence. Additionally, the PFC model uses parallel bonding parameters to characterize intact rock but does not account for slip at the weak interlayer interfaces, resulting in lower simulated values compared to measured values49. Despite the local discrepancies, the overall trends among the three datasets are consistent. At a depth of 141 m, the root mean square error (RMSE)50 among the three values is approximately 260 mm.

The analysis indicated that the surface cracks induced by high-intensity mining primarily exhibit a band-like distribution above the boundary of the mined-out area. Furthermore, the density of these cracks shows a nonlinear positive correlation with the distance of the working face advancement. Based on the subsidence curves of different depth rock layers, it is evident that the area 50–150 m from the excavation face is a zone of dense cracking, while the rock layers at depths of 110–142 m are identified as the critical fracture layers. The main subsidence profile coincides with the region of dense surface cracks, suggesting that crack propagation is driven by the energy released from roof fractures. Both the numerical and theoretical models effectively represent the overall trend of increasing subsidence with the increase in lag distance.

Although the theoretical and numerical models developed in this study effectively characterize the overburden failure patterns and surface damage under high-intensity mining of shallow thick coal seams in the Shendong mining area, their applicability still requires further validation under specific geological and mechanical conditions. The assumption of an elastic, homogeneous, and continuous medium does not adequately consider the influence of discontinuities such as joints and bedding on the failure process. Meanwhile, the PFC model, based on a two-dimensional plane strain assumption, inherently lacks the ability to represent stress release effects in the inclined direction and the three-dimensional propagation of fractures. Notably, As shown in Figs. 6 and 9, the proposed model quantitatively captures the coupling mechanism between high-intensity mining (12 m/d) and the thickness-to-span ratio of key strata, laying a solid foundation for future studies. Future research may focus on innovations in multi-scale modeling, such as coupling PFC micro-simulations with continuum finite element analysis to accurately simulate fracture network propagation under complex geological conditions, thereby enhancing the model’s applicability in complex mining areas with high in-situ stress and multi-seam extraction.

Conclusion

This study, conducted in the Shen Dong mining area using a typical working face as the engineering background, investigates the overburden displacement and stress distribution characteristics, fracture evolution, breakage and collapse behavior, and surface subsidence patterns under high-intensity mining conditions of shallow, thick coal seams at various mining distances. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

As the working face advances, the fracture and collapse of the overlying rock exhibit staged changes. The initial fracture distance of the basic roof is approximately 80 m, with periodic fracture spacing ranging from 40 to 60 m. The main critical layer significantly influences the stability of the rock strata and surface subsidence. The simulation results align closely with field observations, indicating that the model can effectively reflect the fracture and collapse patterns of the rock layers during coal mining.

-

The stress evolution in the mined-out area is divided into three stages: the overall depressurization stage (stress < 2 MPa), the unimodal stress concentration stage (peak value of 3.95 MPa), and the bimodal stress concentration stage (peak value of 11.2 MPa). The displacement of the overlying rock exhibits a layered response in subsidence, extending from the immediate roof to the critical layer and surface. Ultimately, during the stage of excessive mining, the surface subsidence reaches 443 mm, while the cumulative subsidence of the basic roof totals 4158 mm. The consistency between the subsidence range and measured results indicates that the synergistic effect of stress and displacement facilitates the fracturing of the overlying rock.

-

The fractures in the overlying rock primarily consist of horizontal layers and vertical breaks. After fracturing, the critical layer forms a “masonry beam” structure that suppresses further crack propagation through horizontal compressive forces. The distribution of porosity is controlled by layering, compaction, and closure processes. The high flexural strength of the critical layer (8# fine sandstone) provides a significant barrier effect against crack propagation.

-

Although the model still has limitations in accounting for the rheological effects of weak interlayers—resulting in slightly lower simulated subsidence values than the measured data in the 50–100 m range—the constructed theoretical and numerical models of overburden fracturing and surface subsidence effectively capture the overall deformation trend. The predicted surface subsidence shows a high degree of correlation with the measured values in the mid-to-far field (150–300 m). Through the calibration of microscopic parameters, the numerical model accurately simulates the fracturing behavior of key strata during coal seam extraction.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhu, H. et al. Development mechanism of mining-induced ground fissure for shallow burial coal seam in the mountainous area of southwestern china: a case study. Acta Geodyn. Geomater. 15(4), 349–362 (2018).

Jiang, L. et al. Dynamic Analysis of the Rock Burst Potential of a Longwall Panel Intersecting with a Fault. Rock Mec. Rock Eng. 53(4), 1737–1754 (2020).

Palchik, V. Bulking factors and extents of caved zones in weathered overburden of shallow abandoned underground workings. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 79, 227–240 (2015).

Wang, F. et al. Damage and Failure Evolution Mechanism for Coal Pillar Dams Affected by Water Immersion in Underground Reservoirs. Geofluids 1, 2985691 (2019).

Guney, A. et al. Analysis of surface subsidence due to longwall mining under weak geological conditions: Turgut basin of Yatagan-Mugla (Turkey) case study. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 33(7), 445–461 (2019).

Ma, H. et al. Environmentally sustainable mining: a case study on surface subsidence control of grouting into overburden. Environ. Earth Sci. 78(10), 320 (2019).

Zha, E. et al. Long-Term Monitoring and Early Warning of Coal Mine Underground Reservoirs-A Case Study in Shigetai Coal Mine. Sustainability. 16(23), 3390 (2024).

Zhang, K. et al. Effects of coal mining disturbance on spatial and temporal distribution of soil water content in Northwest China-based on 3D EBK model. Hydrol. Process. 38(9), 15277 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Dynamic Changes in Surface Damage Induced by High-Intensity Mining of Shallow. Thick Coal Seams in Gully Areas. Adv. Civ. Eng. 1, 5151246 (2020)

He, W. et al. Field and simulation study of the rational coal pillar width in extra-thick coal seams. Energy Sci. Eng. 8(3), 627–646 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Study on Reasonable Filling Width of Gob-side Entry Retaining and Its engineering Application. Environ. Protect. Resour. Exploit. 807, 2288–2293 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Formation Mechanism and Reduction Technology of Mining-Induced Fissures in Shallow Thick Coal Seam Mining. Shock. Vib. 1, 1980817 (2017).

Wang, B. et al. Research on the dynamic evolution law of fissures in shallow-buried and short-distance coal seam mining in Lijiahao Coal Mine. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 5625 (2023).

Peng, N. et al. Analysis of Dynamic Evolution of Surrounding Rock Movement and Stress-Fracture in the Upward and Repeated Mining of Close-Distance Coal Seams. Adv. Civ. Eng. 1, 5548837 (2024).

Yuan, A. et al. Movement laws of overlying strata and prevention measures of dynamic disasters under deep adjacent coal seam group with high gas. Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk. 11(1), 2339–2359 (2020).

Liu, W. et al. Study on overburden failure characteristics in deep thick loose seam and thick coal seam mining. Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk. 11(1), 632–653 (2020).

Hu, S. et al. Study on overlying rock movement and mine pressure behavior in shallow-buried close coal multi-seam mining. Alex. Eng. J. 105, 578–587 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Study on the Structural Instability Characteristics of Interlayer Rock Strata During Mining Under Interval Goaf in Shallow Coal Seams. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 14(24), 11870 (2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Structural evolution of overburden and surface damage caused by high-intensity mining with shallow depth. J. China Coa; Soc. 45(08), 2728–2739 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Stress Evolution and Failure Characteristics of Overburden During Multi-Stope Mining for a Gently Inclined Thin Orebody. Mining Metall. Explor. 40(2), 637–653 (2023).

Hou, E. et al. Ground surface development characteristics of shallow double coal seam staggered mining based on particle flow. J. Mining Strata Control Eng. 2(1), 20–28 (2020).

Xie, J. et al. Influence of Key Strata on the Evolution Law of Mining-Induced Stress in the Working Face under Deep and Large-Scale Mining. Minerals 13(7), 983 (2023).

Song, Z. et al. The Influence of the Morphological Characteristics of Mining-Induced Ground Fissures on the Spatiotemporal Distribution of Soil Moisture. Water 16(17), 2496 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Shear behavior of intact granite under thermo-mechanical coupling and three-dimensional morphology of shear-formed fractures. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15(3), 523–537 (2023).

Pan, W. et al. The Spatial Evolution Law and Water Inrush Mechanism of Mining-Induced Overburden in Shallow and Short Coal Seam Group. Sustainability. 14(9), 5320 (2022).

Alejano, L. et al. Ground reaction curves for tunnels excavated in different quality rock masses showing several types of post-failure behaviour. Tunn. Underground Space Technol. 24(6), 689–705 (2009).

Yang, Z. et al. Mechanism of rock burst caused by fracture of key strata during irregular working face mining and its prevention methods. Int. J. Mining Sci. Technol. 29(6), 889–897 (2019).

Cheng, G. et al. Research on Spatiotemporal Continuous Information Perception of Overburden Compression-Tensile Strain Transition Zone during Mining and Integrated Safety Guarantee System. Sensors. 24(17), 5856 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Influence of main roof thickness-span ratio on the initial cracking induced instability in fully mechanized longwall face. J. China Coal Soc. 44(01), 94–104 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Effect of working face length and advancing speed on strata behaviors in high-intensity mining. Rock Soil Mech. 36(S2), 45 (2015).

Diederichs, M. et al. Stability of large excavations in laminated hard rock masses: the voussoir analogue revisited. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 36(1), 97–117 (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. Elastoplastic stability analysis of mine haulage drift in the vicinity of mined stopes. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 45(4), 574–593 (2008).

Alessandrini, G. et al. Global stability for an inverse problem in soil-structure interaction. Proc. Roy. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 471(2179), 0117 (2015).

Meng, F. et al. Subsidence Prediction Method Based on Elastic Foundation Beam and Equivalent Mining Height Theory and Its Application. Appl. Sci. 14(19), 8766 (2024).

Yin, X. Application and research on cutting block structure of overburden strata in shallow buriedworkface with ultra-large mining height. Grad. Sch. China Coal Res. Inst. (2020).

Cui, J. et al. Deformation and Fracturing Mechanism of Goaf Slope. J. Mining Saf. Eng. 25(04), 409–414 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Stability and Force Chain Characteristics of Inclined Step Cutting Body" in Stope. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 11(21), 10276 (2021).

Lu, A. et al. Numerical Simulation Study on Pressure-Relief Effect of Protective Layer Mining in Coal Seams Prone to Rockburst Hazard. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 6421–6440 (2024).

Chen, P. Research progress on pfc2d simulation of crack propagation characteristics of cracked rock. J. Eng. Geol. 26(02), 528–539 (2018).

Cho, N. et al. A clumped particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 44(7), 997–1010 (2007).

Potyondy, D. et al. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41(8), 1329–1364 (2004).

Wang, T. et al. Simulation of hydraulic fracturing using particle flow method and application in a coal mine. Int. J. Coal Geol. 121, 1–13 (2014).

Xu, J. et al. Study on the influence of key strata movement on subsidence. J. China Coal Soc. 25(02), 122–126 (2000).

Wang, B. et al. Research on the dynamic evolution law of fissures in shallow-buried and short-distance coal seam mining in Lijiahao Coal Mine. Sci. Rep. 13, 5625 (2023).

Brady, B. et al. Rock mechanics: for underground mining. Springer science & business media (2006).

Yuan, A. et al. Movement laws of overlying strata and prevention measures of dynamic disasters under deep adjacent coal seam group with high gas. Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 11(1), 2340–2360 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Evaluation of surface subsidence due to inclined coal seam mining: A case study in the 1930 Coal Mine. China. Nat. Resour. Res. 31, 3303–3317 (2022).

Wu, L. Study on the law and control of mine pressure appearance of shallow burial depth and close distance coal seams in lijiahao coal mine [D] (Liaoning Tech. Univ, 2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Study on detection methods for three-dimensional morphology of mining-induced ground fissures and accuracy evaluation. Coal Sci. Technol. 48(09), 236–242 (2020).

Qi, Q. et al. Spatial prediction of soil organic carbon in coal mining subsidence areas based on RBF neural network. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 10, 30 (2023).

Funding

This work is supported by Open Fund of State Key Laboratory of Water Resource Protection and Utilization in Coal Mining (Grant No. GJNY-20–113-18, GJNY-21–44), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52004170) and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202303021221008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. Z.:Methodology; Conceptualization; Funding acquisition. J.Z.: Writing-Original Draft; Numerical simulation; Investigation; Formal analysis. Z.X.: Investigation; Writing-review&editing. J.Z.: Data Curation; Investigation. S.D.: Methodology; Resources. S.W.: Project administration. X.L.: Investigation; administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhang, J., Xu, Z. et al. Overburden breakage and surface damage evolution under high-intensity mining of shallow coal seams: evidence from Shendong mining area. Sci Rep 15, 23152 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05177-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05177-9