Abstract

Ludwigia adscendens subsp. diffusa (Forssk.) P.H. Raven, also known as L. stolonifera, is an aquatic herb belonging to family Onagraceae and widely distributed in canals and drains in the Nile Delta, Egypt. The main goal of the current study is to investigate the metabolic profile of L. adscendens aerial parts using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS/MS) and investigation of its anti-inflammatory activity. A total of 168 metabolites were identified by UPLC-MS/MS analysis in negative and positive modes belonging to several phytochemical classes including phenolics (57), flavonoids (26), terpenoids (25), sterols (23), fatty acids (11), coumarins (7) organic acids (5), sugar derivatives (5), lactones (4), acids (3), and glycoside (2). The UPLC-MS analysis of L. adscendens revealed identification of a diverse array of phytochemicals which contribute to its potential pharmacological properties. The identification of bioactive metabolites in L. adscendens aerial parts including gallic acid, quercetin, ellagic acid, and betulinic acid can impart biological activities including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. The anti-inflammatory activity was investigated for L. adscendens methanol and ethyl acetate extract using nitric acid inhibition assay revealing IC50 of 26.4 and 23.9 µg/ml, respectively, compared to resveratrol as a standard anti-inflammatory with IC50 value of 14.2 µg/ml. These findings can highlight the importance of L. adscendens aerial parts as a potential source of bioactive metabolites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, great interest has been paid to plant-based phytochemicals including phenolic acids, flavonoids, steroids, terpenoids, and others, owing to their myriad health benefits1. Onagraceae also known as evening primrose or willowherb family, is a family of flowering plants widely distributed in every continent, from tropical to boreal regions. Onagraceae comprises about 17 genera and 650 species of trees, shrubs, and herbs distributed into two subfamilies and seven tribes2. Genus Ludwigia is a member of the Ludwigioideae subfamily distributed in South and North America, and comprises about 82 species of aquatics plants3.

Ludwigia species are reported for their diverse biological properties including antidiabetic, cytotoxicity, antioxidant, hepatoprotective antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities. For instance, L. hyssopifolia (G.Don) Exell. aerial parts methanolic extract showed potent anti-inflammatory activity4 L. octovalvis (Jacq.) P.H.Raven aqueous ethanolic extract showed antidiabetic effect5and L. peploides (Kunth) P.H.Raven leaves methanolic extract revealed cytotoxic, analgesic, antimicrobial, antidiarrheal and hypolipidemic properties2. In the Egyptian flora, Ludwigia genus is represented by two species: L. erecta (L.) Hara. and L. stolonifera (Guill. & Perr.) P.H.Raven6.

Ludwigia adscendens subsp. diffusa Forssk. Also known as Ludwigia stolonifera, it emerged as one of the most important aquatic plants widely distributed in canals and drains crossing the cultivated lands in the Nile Delta. L. adscendens is well known for its economic importance, being used in water bioremediation to help in improving drinking water quality3. Owing to its ability to remove toxic contaminants including heavy metals such Pb, Cd, and Cr from aquatic ecosystems, L. stolonifera roots and leaves are used as water biofilters7. Moreover, L. stolonifera is rich in bioactive secondary metabolites which are imparted for their biological activities including antioxidant, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, and cytotoxic activities3,8,9.

Nowadays, different metabolomics tools are widely applied to profile plant-based primary and secondary metabolites10. LC-MS is well-suited metabolomics approach suited for the identification of non-volatile secondary metabolites in herbal materials11. Several studies have demonstrated that variety of antioxidant phytoconstituents also display a potent anti-inflammatory effect12,13. L. adscendens ethyl acetate extract possesses antioxidant activity9 so this study focuses on investigation of its anti-inflammatory effect.

The main goal of the current study is to evaluate the phytochemical profile in L. adscendens subsp. diffusa aerial parts using UPLC-MS/MS in negative and positive modes. Further investigation of the anti-inflammatory activity L. adscendens extract was employed using nitric oxide inhibition assay.

Results and discussion

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS/MS) analysis was employed for L. adscendens aerial parts methanol extract in both positive and negative modes (Fig. 1). Compounds were eluted within 25 min from the most polar to the least polarity ones according to the sequence of elusion. The identification was depended on comparison of the high-resolution mass spectra information with phytochemical dictionary of natural product databases and MS/MS and with that reported in the literature. A total of 168 metabolites were identified by UPLC-MS analysis in negative and positive modes (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Chemical metabolites identified in Ludwigia stolonifera by UPLC-MS/MS negative and positive modes

UPLC-MS/MS analysis of L. adscendens aerial parts in negative and positive (Fig. 1A and B) revealed the annotation of 168 metabolites (Table 1; Fig. 2) belonging to several phytochemical classes including phenolics (57), flavonoids (26), terpenoids (25), sterols (22), fatty acids (11), coumarins (8) organic acids (5), sugar derivatives (5), lactones (4), acids (3), and glycoside (2). Flavonoids and phenolics were identified as the most abundant metabolite classes which enhance the biological properties of L. adscendens including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

Phenolic compounds

Phenolic compounds were identified as the most abundant class represented by 57 peaks. Phenolic compounds are ubiquitously distributed phytochemicals found in most plants and possess numerous bioactive properties including antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory14. Peaks 60, 61, and 75 were assigned to gallic acid (m/z 169.0140, C7H6O5−)15 and its derivatives, gallic acid hexoside (C13H16O10−)16 and digallic acid (C14H10O9−), respectively. Gallic acid and its derivatives are potential biological importance including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties17. Methyl gallate (peak 67) and pyrogallol gallate (peak 66) appeared at m/z [M-H]− 183.0292 (C8H8O5−) and 293.0289 (C13H10O8−)18respectively. Gallate deratives were previously identified in L. adscendens aerial parts3 and has been reported to exhibit hepatoprotective and anticancer effects19. Peaks 73, 74, and 18 were annotated for ellagic acid (m/z [M-H]− 300.9983 C14H6O8)20 and its derivatives, such as gallagic acid and ellagic acid dihydrates, respectively. Ellagic acid and its derivatives are ellagitannins with potent antioxidant and antitumor properties21. Ferulic acid (peak 59) was identified (m/z [M-H]− 193.0498 C10H10O4−) is a hydroxycinnamic acid with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties22. Peak 70 were assigned to dihydroxycaffeic acid (m/z [M-H]− 211.0239 C9H8O6−) which possesses strong neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties23. Gingerol (Peak 59) was detected in L. adscendens aerial parts and is well known for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities24. Simple phenolics were identified including pyrogallol (peak 86) [M + H]+ at m/z 127.0388 (C6H6O3+) and 2-hydroxyethyl gallate (peak 87) [M + H]+ at m/z 215.0525 (C9H10O6+) with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties25. Peak 107 was identified as feruloyl lactate and peak 98 was identified as Sinapyl aldehyde [M + H]+ at m/z 209.0782 (C11H12O4+)26. Sinapyl aldehyde is a precursor in lignin biosynthesis and contributes to plant cell wall integrity and well known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties26. Peak 102 was assigned to zingerone, which is a phenolic compound with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties27.

Flavonoids

Flavonoids, a group of natural substances with variable phenolic structures with potential health benefits owing to their anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic and anti-carcinogenic properties28. Flavonoids represented by 26 peaks were identified in L. adscendens aerial parts. Both O- & C-flavonoid glycosides were identified by different fragmentation pattern that distinguished between the two types of glycosidic linkages. Flavonols and flavone O-glycosides were identified according to neutral loss of sugar moieties; [M-H]− [179, 161, 149 & 131 amu] which assigned for ions loss of (hexose, deoxyhexose, and pentose units), respectively. Peaks 33 and 26 were annotated as quercetin (m/z [M-H]− 301.0342 C15H10O7−) and quercetin 3-O-hexoside (m/z 463.0862 C21H20O12−), respectively. Peaks 29, 31 and 46 were assigned to kaempferol-3-O-hexoside29 kaempferol-3-O-arabinoside30 and apigenin-8-C-hexoside31 respectively. Moreover, myricetin (peak 45) (m/z 317.0293 C15H10O8−) and myricetin-3-O-hexoside (peak 27) (m/z 479.0810 C21H20O13−) were identified in L. adscendens aerial parts. Peak 30 and peak 22 were annotated as quercetin 3-(2’’-galloyl-pentoside) (m/z [M-H]− 585.055 C27H22O15) and quercetin 3-O-(6’’-galloyl-hexoside) (m/z [M-H]− 615.0963 C28H42O16−) which is related to previously isolated compounds from in L. adscendens aerial parts3. Moreover, peaks 36, 38, and 40 were identified as quercetin derivatives26 and including quercetin 3-O-glucuronide [M + H]+ at m/z 479.0822 (C21H18O13+), quercetin 3-O-pentoside [M + H]+ at m/z 435.0923 (C20H18O11+), and quercetin 3-O-deoxyhexoside [M + H]+ at m/z 449.1078 (C21H16O13+)32 respectively. Quercetin derivatives are reported for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties33. Quercetin has been reported to modulate signaling pathways involved in cancer progression32. Flavonoids can contribute to the biological importance of L. adscendens aerial parts owing to their myriad pharmacological properties.

Triterpenes and sterols

Triterpenoids represented by 25 peaks were identified in L. adscendens aerial parts. Triterpenoids play a pivotal role in human health owing to their pharmacological activities including antidiabetic properties, neuropharmacological, and anti-inflammatory effects34. Peaks 143, 148, and 160 were assigned to protobassic acid (m/z [M-H]− 503.3355 C30H48O6−), asiatic acid (m/z [M-H]− 487.3407 C30H48O5−), and betulinic acid (m/z [M-H]− 455.3513 C30H48O3−)35. Such triterpenoids were reported for their significant biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and hepatoprotective effects36. Peak 155 was annotated as maslinic acid (m/z [M-H]− 471.3461 C30H48O4−) which a pentacyclic triterpenoid with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties37. Hederagenin (peak 154) was previously identified as the aglycone of triterpenoid saponins isolated from L. adscendens aerial parts3. It has been reported for its potential pharmacological activities including antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, antineurodegenerative, antihyperlipidemic, antidiabetic, and antiviral activities38. Moreover, triterpenoids were detected in positive mode among which peak 169, 170, and 171 were identified as ganoderic acid, asiatic acid triacetate and dihydrosarcostin, respectively. These triterpenoid compounds are found in medicinal plants and contribute to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties36.

Likewise, sterols were identified by 23 peaks represented mainly by stoloniferone S (Peak 150) and viticosterone E (Peak 135) with potential bioactive properties39. Plant sterols play a pivotal role in human health through several biological properties including cardioprotective, neuroprotective, and anti-aging40. Moreover, peak 116 and 131 were assigned to momordicoside E (C37H60O12) and agosterol F (C31H50O7) which are steroidal saponin with anti-inflammatory properties41. Moreover, sterols were detected in positive mode represented by several peaks among which 117, 126, 128, and 129 were identified as sarcostin [M + H]+ at m/z 383.2404 (C21H34O6+), β-sitosterol-3-O-arabinobenzoate [M + H]+ at m/z 651.4591 (C41H62O6+), Stigmasterylferulate [M + H]+ at m/z 589.4283 (C39H56O4+), and stigmastadiene [M + H]+ at m/z 397.3827 (C29H48+).

Fatty acids

Fatty acids were detected mainly by 11 peaks, among which linolenic acid (peak 12)42 and ricinoleic acid (peak 13) were identified in negative mode. Linolenic acid [M-H]− at m/z 277.2163 (C18H30O2−) is an essential omega-3 fatty acid with anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects43. Moreover, ricinoleic acid [M-H]− at m/z 297.2422 (C18H34O3−) is a hydroxy fatty acid with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties44. Peaks 15 and 20 were assigned to colneleic acid [M + H]+ at m/z 295.2268 (C18H30O3+)45 and stearidonic acid [M + H]+ at m/z 277.2164 (C18H28O2+)10,11.

Coumarins

Coumarins represented by 7 peaks were detected in L. adscendens aerial parts and detected only in positive mode. Coumarins are considered as biologically active metabolites with potential pharmacological properties including anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer46. Peaks 10, 4, 7, and 9 were identified as ethynyl coumarin [M + H]+ at m/z 171.0451 (C11H6O2+), coumarin-3-carboxylic acid, penicimarin F, and 7-methoxycoumarin [M + H]+ at m/z 419.0977 (C20H18O10+).

Organic acids

Aliphatic organic acids are the important bioactive compounds found in medicinal plants and play a key role in flavor, maintain nutritional value as well as their characteristic taste47,48. Among organic acids, malic and citric acids are mainly produced in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and accumulated in various plant species47. Peaks 55 and 56 were assigned to citric acid (m/z [M-H]− 191.0192 C6H8O7) and malic acid (m/z [M-H]− 133.0139 C4H6O5)42. These acids also contribute to the sour taste of plant tissues and play roles in pH regulation48. Peak 58 was assigned to dehydroascorbic acid m/z 173 C6H6O6−49 indicating the presence of ascorbic acid metabolism in L. adscendens aerial parts which imparts to its potent antioxidant potential.

Anti-inflammatory activity

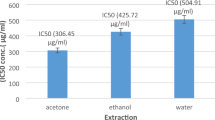

In daily routine, the human body is largely exposed to inflammation by environmental pollutants, infections (bacteria, viruses, and fungi) and other physical and chemical agents50. Inflammation is a protective strategy that stimulate immune response to protect from tissue injury and other noxious conditions and promote the healing of damaged tissue50. Recently, several diseases were linked to the inflammatory response including atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases13. Elevation of NO level is used as a marker for inflammatory response as manifested by elevated exhaled nitric oxide (NO) in asthmatics which indicate airways inflammation13,51. NO is an important chemical mediator produced by endothelial cells, macrophages, and neurons and play a key role in the immune system’s host defense mechanism and regulate blood vessel tone in vascular systems52. NO is considered as a pro-inflammatory mediator that induces inflammation due to over production in abnormal situations13,53. Hence, inhibition of excess nitric oxide is one of the possible mechanisms of anti-inflammatory agents. Recently, plant-based phytochemicals identified in medicinal plants’ crude extracts and/or pure compounds, are widely used as potential sources of anti-inflammatory agents54. Several phytoconstituents widely distributed in plants and possess anti-inflammatory activity including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, steroids, and saponins54,55. The ant-inflammatory activity of L. adscendens aerial parts methanol extract and ethyl acetate fraction was investigated via NO inhibitory assay (Table S1). Results revealed that methanol extract and ethyl acetate fraction showed potent anti-inflammatory with calculated IC50 of 26.4 and 23.9 µg/ml, respectively, compared to resveratrol as standard anti-inflammatory with IC50 value of 14.2 µg/ml (Fig. 3). Such anti-inflammatory activity of L. adscendens aerial parts is manifested by its richness with bioactive phytochemicals including phenolics, flavonoids, triterpenoids, and steroids. Several metabolites were identified and reported for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Gallic acid and its derivatives are potential biological importance including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties17. Gallic acid can reduce inflammation via inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines56. Moreover, quercetin57 ellagic acid58 and betulinic acid59 contributes to the significant antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activity33 of L. adscendens aerial parts. Such results are compatible with other previous studies on several species belonging to the family Onagraceae, which reported to exert a potent anti-inflammatory activity60. In another study, Jussiaea repens L. aerial parts ethylacetate extract revealed in vitro anti-inflammatory activity61. Epilobium angustifolium and Epilobium montanum aerial parts dichloromethane extracts were tested for the anti-inflammatory activity revealing a potent effect62.

Conclusion

Phytochemical profiling of L. adscendens aerial parts via UPLC-MS/MS analysis in negative and positive modes was introduced herein. A total of 168 metabolites were identified belonging to several phytochemical classes including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, sterols, fatty acids, coumarins, organic acids, sugar derivatives, lactones, acids, and glycoside. Several metabolites were identified in L. adscendens aerial parts with significant biological importance including gallic acid and gallate derivatives, quercetin derivatives, ellagic acid, gingerol and betulinic acid which can contribute to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Investigation of the anti-inflammatory activity of L. adscendens methanol and ethyl acetate extract via nitric acid inhibition assay revealed potent activity with IC50 of 26.4 and 23.9 µg/ml, respectively, compared to resveratrol with IC50 value of 14.2 µg/ml. These findings can highlight the importance of L. adscendens aerial parts as a potential source of bioactive metabolites. Further isolation and biological investigation of the bioactive metabolites using different chromatographic techniques are recommended in future work.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The aerial parts of L. adscendens subsp. diffusa (Forssk.) P.H. Raven were collected from the Nile River at El Qanatir Al-Khayriyah, El Qulyoubia governorate (30.193583°N 31.132064°E), Egypt in September 2024. The botanical identification of the plant was confirmed by Prof. Dr. Rim Hamdy, Professor of plant taxonomy, Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt. A voucher specimen with the number Lus2/2024, has been deposited at the Pharmacy Department of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Egyptian Russian University.

Plant extraction

The air-dried aerial parts of L. adscendens (250 g) were macerated in methanol at room temperature, stirring occasionally, and the operation was repeated three times until being exhausted. The dried methanol extract was obtained by concentrating under reduced pressure using a Rotary evaporator at 50 oC to yield 30 g dry methanol extract. About 10 g was kept in closed contained and kept in the refrigerator for UPLC-MS analysis. About 20 g of the obtained methanol extract was suspended in distilled water and sequentially partitioned with different immiscible solvents (petroleum ether, chloroform and ethyl acetate solvents) starting with petroleum ether followed by fractionation with chloroform, and finally ethyl acetate. Ethyl acetate fraction (7 g) was obtained and used for further biological investigation.

Chemicals

HR-UPLC/MS/MS: Milli-Q water and solvents; formic acid and acetonitrile of LC-MS grade, J. T. Baker (The Netherlands). Nitric oxide and all chemicals used in biological investigation were supplied by Sigma Aldrich Chemie GmbH, St. Louis, MO.

HR-UPLC-MS/MS analysis

Dried methanol extract (10 mg) was extracted by adding 2 mL of 100% MeOH, containing 10 µgmL−1 umbelliferone as an internal standard and sonicated for 20 min with frequent shaking, then centrifuged at 12 000 × g for 10 min to remove debris. A sample of 3 µl of 100% methanol extract was subjected to chromatographic separation using an I-Class UPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). The filtered extract through a 0.22-µm filter was subjected to solid-phase extraction using a C18 cartridge (Sep Pack, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) as previously described11. UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS analysis was carried out using an ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Reversed-phase sorbent column: HSS T3 (C18, 100 × 1.0 mm), particle size: 1.8 μm: (Waters). The annotation of metabolites was based on full mass spectra, molecular formula with an (error < 5 ppm), and by comparing fragmentation pattern with available literature and phytochemical dictionary of natural products database63. Chromatographic separation was carried out at 40 °C, using a Waters HSS T3 column (1.0 mm × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) with mobile phases A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (acetonitrile). The flow rate was set at 0.15 mL/min. The gradient profile was as follows: 0–1 min, 5–5% B; 1–11 min, 5–100% B; 11–19 min, 100% B; 19–20 min, 100%−5% B; 20–25 min, 5% B. Mass spectrometric detection was carried out on Waters Synapt XS mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) equipped with an ESI source. The full scan data were acquired from 50 to 1200 Da, using a capillary voltage of 4.0 kV for positive ion mode and 3.0 kV for negative ion mode, sampling cone voltage of 30 V for positive ion mode and 35 V for negative ion mode, extraction cone voltage of 4.0 V, source temperature of 140 °C, cone gas flow of 50 L/h, desolvation gas (N2) flow of 1000 L/h and desolvation gas temperature of 450 °C. The collision voltage was set as 5.0 eV for low-energy scan and 25–50 eV for high-energy scan. The collision energy settings (5.0 eV for low-energy scan and 25–50 eV for high-energy scan)11 were selected based on instrument manufacturer recommendations and prior optimization studies to ensure effective fragmentation of a wide range of metabolites with diverse structural properties. These values provide a balance between low-energy precursor ion detection and adequate high-energy fragmentation required for structural elucidation in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode.

Nitric oxide (NO) Inhibition activity

NO inhibition activity of the tested sample was determined by using a sodium nitroprusside (SNP)64,65. NO radical generated from SNP in aqueous solution at physiological pH reacts with oxygen to produce nitrite ions that were measured by the Greiss reagent. The reaction mixture (2 mL) containing various concentrations of the tested samples and SNP (10 mM) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) was incubated at 25 ºC for 150 min. At the end of the incubation period, 1 mL of reaction mixture samples was diluted with 1 mL Greiss reagent (1% sulphanilamide (w/v) in 5% phosphoric acid (v/v) and 0.1% naphthyl ethylene diamine dihydrochloride). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for a further 30 min. The absorbance of these solutions was measured at 546 nm against the corresponding blank solution (without sodium nitroprusside). Resveratrol was used as a reference standard. All the tests were performed in triplicate. The percentage inhibition activity was calculated using the formula:

Where, A control is the absorbance of the control reaction at 546 nm and Atest represents the absorbance of a test reaction at the same wavelength. Tested material concentration providing 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated from the graph plotting inhibition percentage against concentration.

Statistical analysis

The results of biological investigation were analyzed in triplicate and displayed as average ± standard deviation of the mean (SD) (Table S1).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Savithramma, N., Rao, M. L. & Suhrulatha, D. Screening of medicinal plants for secondary metabolites. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 8, 579–584 (2011).

Shawky, E. M., Elgindi, M. R., Ibrahim, H. A. & Baky, M. H. The potential and outgoing trends in traditional, phytochemical, economical, and ethnopharmacological importance of family onagraceae: A comprehensive review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 281, 114450 (2021).

Baky, M. H., Elgindi, M. R., Shawky, E. M. & Ibrahim, H. A. Phytochemical investigation of Ludwigia adscendens subsp. Diffusa aerial parts in context of its biological activity. BMC Chem. 16, 112 (2022).

Praneetha, P., Reddy, Y. N. & Kumar, B. R. In vitro and In vivo hepatoprotective studies on methanolic extract of aerial parts of Ludwigia hyssopifolia G. Don Exell. Pharmacognosy Magazine 14 (2018).

Lin, W. S. et al. Ludwigia octovalvis extract improves glycemic control and memory performance in diabetic mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 207, 211–219 (2017).

Amer, W. M., Hamdy, R. S. & Hamed, A. B. in Egypt Journal of Botany, 6 th International conference. 11–12.

Saleh, H., Bayoumi, T., Mahmoud, H. & Aglan, R. Uptake of cesium and Cobalt radionuclides from simulated radioactive wastewater by Ludwigia stolonifera aquatic plant. Nucl. Eng. Des. 315, 194–199 (2017).

Marzouk, M., Soliman, F., Shehata, I., Rabee, M. & Fawzy, G. Flavonoids and biological activities of Jussiaea repens. Nat. Prod. Res. 21, 436–443 (2007).

Baky, M. H., Shawky, E. M., Elgindi, M. R. & Ibrahim, H. A. Comparative volatile profiling of Ludwigia stolonifera aerial parts and roots using VSE-GC-MS/MS and screening of antioxidant and metal chelation activities. ACS Omega. 6, 24788–24794 (2021).

Farag, M. A. et al. Comparison of Balanites aegyptiaca parts: metabolome providing insights into plant health benefits and valorization purposes as analyzed using multiplex GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR-based metabolomics, and molecular networking. RSC Adv. 13, 21471–21493 (2023).

Fayek, N. M. et al. Metabolome classification of Olive by-products from different oil presses providing insights into its potential health benefits and valorization as analyzed via multiplex MS‐based techniques coupled to chemometrics. Phytochemical Analysis (2024).

Sala, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of Helichrysum italicum. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 54, 365–371 (2002).

Rao, U., Ahmad, B. A. & Mohd, K. S. In vitro nitric oxide scavenging and anti-inflammatory activities of different solvent extracts of various parts of Musa paradisiaca. Malaysian J. Anal. Sci. 20, 1191–1202 (2016).

de la Rosa, L. A., Moreno-Escamilla, J. O. & Rodrigo-García, J. & Alvarez-Parrilla, E. in Postharvest physiology and biochemistry of fruits and vegetables 253–271Elsevier, (2019).

Abidi, J. et al. Use of ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry system as valuable tool for an untargeted metabolomic profiling of Rumex Tunetanus flowers and stems and contribution to the antioxidant activity. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 162, 66–81 (2019).

Mekky, R. H. et al. Profiling of phenolic and other compounds from Egyptian cultivars of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and antioxidant activity: A comparative study. RSC Adv. 5, 17751–17767 (2015).

Bai, J. et al. Gallic acid: Pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 133, 110985 (2021).

Ammar, S. et al. Untargeted metabolite profiling and phytochemical analysis based on RP-HPLC‐DAD‐QTOF‐MS and MS/MS for discovering new bioactive compounds in Rumex algeriensis flowers and stems. Phytochem. Anal. 31, 616–635 (2020).

Anzoise, M. L. et al. Potential usefulness of Methyl gallate in the treatment of experimental colitis. Inflammopharmacology 26, 839–849 (2018).

Granica, S., Czerwińska, M. E., Piwowarski, J. P., Ziaja, M. & Kiss, A. K. Chemical composition, antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activity of extracts prepared from aerial parts of Oenothera biennis L. and Oenothera paradoxa Hudziok obtained after seeds cultivation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 801–810 (2013).

Landete, J. & Ellagitannins Ellagic acid and their derived metabolites: A review about source, metabolism, functions and health. Food Res. Int. 44, 1150–1160 (2011).

Mancuso, C. & Santangelo, R. Ferulic acid: Pharmacological and toxicological aspects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 65, 185–195 (2014).

Maurya, D. K. & Devasagayam, T. P. A. Antioxidant and prooxidant nature of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives ferulic and caffeic acids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 48, 3369–3373 (2010).

Sweilam, S. H., Hafeez, A. E., Mansour, M. S., Mekky, R. H. & M. A. & Unravelling the phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential of different parts of Rumex vesicarius L.: A RP-HPLC-MS-MS/MS, chemometrics, and molecular Docking-Based comparative study. Plants 13, 1815 (2024).

Gupta, A., Jeyakumar, E. & Lawrence, R. Pyrogallol: a competent therapeutic agent of the future. Biotech. Env Sc. 23, 213–217 (2021).

Alotaibi, B. et al. Antimicrobial activity of Brassica rapa L. flowers extract on Gastrointestinal tract infections and antiulcer potential against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in rats supported by metabolomics profiling. J. Inflamm. Res., 7411–7430 (2021).

Akaras, N., Gur, C., Kucukler, S. & Kandemir, F. M. Zingerone reduces sodium arsenite-induced nephrotoxicity by regulating oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and histopathological changes. hemico-biological Interact. 374, 110410 (2023).

Panche, A. N., Diwan, A. D. & Chandra, S. R. Flavonoids: an overview. J. Nutritional Sci. 5, e47 (2016).

Farag, M. A., Weigend, M., Luebert, F., Brokamp, G. & Wessjohann, L. A. Phytochemical, phylogenetic, and anti-inflammatory evaluation of 43 Urtica accessions (stinging nettle) based on UPLC–Q-TOF-MS metabolomic profiles. Phytochemistry 96, 170–183 (2013).

Zhao, Y. et al. Characterization of phenolic constituents in Lithocarpus polystachyus. Anal. Methods. 6, 1359–1363 (2014).

Elhawary, S. S., Younis, I. Y., Bishbishy, E., Khattab, A. R. & M. H. & LC–MS/MS-based chemometric analysis of phytochemical diversity in 13 Ficus spp.(Moraceae): correlation to their in vitro antimicrobial and in Silico quorum sensing inhibitory activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 126, 261–271 (2018).

Kwon, R. H. et al. Comprehensive profiling of phenolic compounds and triterpenoid saponins from Acanthopanax senticosus and their antioxidant, α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. (2024).

Alizadeh, S. R. & Ebrahimzadeh, M. A. Quercetin derivatives: drug design, development, and biological activities, a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 229, 114068 (2022).

Hill, R. A. & Connolly J. Triterpenoids Natural Prod. Reports 30, 1028–1065 (2013).

Mena, P. et al. Phytochemical profiling of flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and volatile fraction of a Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract. Molecules 21, 1576 (2016).

Hill, R. A., Connolly, J. D. & Triterpenoids Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 90–122 (2017).

Peragón, J., Rufino-Palomares, E. E., Muñoz-Espada, I., Reyes-Zurita, F. J. & Lupiáñez, J. A. A new HPLC-MS method for measuring maslinic acid and oleanolic acid in HT29 and HepG2 human cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 21681–21694 (2015).

Huang, X., Shen, Q. K., Guo, H. Y., Li, X. & Quan, Z. S. Pharmacological overview of Hederagenin and its derivatives. RSC Med. Chem. 14, 1858–1884 (2023).

Mamadalieva, N. Z., Egamberdieva, D. & Tiezzi, A. In vitro biological activities of the components from Silene Wallichiana. Med. Aromat. Plant. Sci. Biotechnol. 7, 1–6 (2013).

Kopylov, A. T., Malsagova, K. A., Stepanov, A. A. & Kaysheva, A. L. Diversity of plant sterols metabolism: the impact on human health, sport, and accumulation of contaminating sterols. Nutrients 13, 1623 (2021).

Liu, J. Q., Chen, J. C., Wang, C. F. & Qiu, M. H. New cucurbitane triterpenoids and steroidal glycoside from Momordica charantia. Molecules 14, 4804–4813 (2009).

Ibrahim, R. M. et al. Unveiling the functional components and antivirulence activity of mustard leaves using an LC-MS/MS, molecular networking, and multivariate data analysis integrated approach. Food Res. Int. 168, 112742 (2023).

Yuan, Q. et al. The review of alpha-linolenic acid: sources, metabolism, and Pharmacology. Phytother. Res. 36, 164–188 (2022).

Nitbani, F. O., Tjitda, P. J. P., Wogo, H. E. & Detha, A. I. R. J. J. O. O. S. Preparation O. ricinoleic acid from castor O.l: A review. J. Oleo Sci. 71, 781–793 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. A simplified synthetic rhizosphere bacterial community steers plant Oxylipin pathways for preventing foliar phytopathogens. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 202, 107941 (2023).

Flores-Morales, V., Villasana-Ruíz, A. P., Garza-Veloz, I., González-Delgado, S. & Martinez-Fierro, M. L. Therapeutic effects of coumarins with different substitution patterns. Molecules 28, 2413 (2023).

Adamczak, A., Ożarowski, M. & Karpiński, T. M. Antibacterial activity of some flavonoids and organic acids widely distributed in plants. J. Clin. Med. 9, 109 (2019).

Shi, Y., Pu, D., Zhou, X. & Zhang, Y. Recent progress in the study of taste characteristics and the nutrition and health properties of organic acids in foods. Foods 11, 3408 (2022).

Pastore, P. et al. Characterization of dehydroascorbic acid solutions by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 15, 2051–2057 (2001).

Ahmed, A. U. An overview of inflammation: mechanism and consequences. Front. Biology. 6, 274–281 (2011).

Libby, P., Ridker, P. M. & Maseri, A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 105, 1135–1143 (2002).

Sharma, J., Al-Omran, A. & Parvathy, S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 15, 252–259 (2007).

Tripathi, P., Tripathi, P., Kashyap, L. & Singh, V. The role of nitric oxide in inflammatory reactions. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51, 443–452 (2007).

Gonfa, Y. H. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of phytochemicals from medicinal plants and their nanoparticles: A review. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 6, 100152 (2023).

Arya Vikrant, A. V. & Arya, M. (2011). Review on anti-inflammatory plant barks.

Sarkaki, A. et al. Gallic acid improved behavior, brain electrophysiology, and inflammation in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 93, 687–694. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2014-0546 (2015).

Lan, T. et al. Exploration of chemical compositions in different germplasm wolfberry using UPLC-MS/MS and evaluation of the in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Quercetin. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1426944 (2024).

Gupta, A. et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective activities of Terminalia bellirica and its bioactive component ellagic acid against diclofenac induced oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Rep. 8, 44–52 (2021).

Oliveira-Costa, J. F. et al. B. P. Anti-inflammatory activities of betulinic acid: a review. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 883857 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Anti-arthritic activities of ethanol extracts of Circaea mollis sieb. & Zucc.(whole plant) in rodents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 225, 359–366 (2018).

Marzouk, M. S., Soliman, F. M., Shehata, I. A., Rabee, M. & Fawzy, G. A. Flavonoids and biological activities of Jussiaea repens. Nat. Prod. Res. 21, 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786410600943288 (2007).

Vogl, S. et al. Ethnopharmacological in vitro studies on austria’s folk medicine—An unexplored Lore in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of 71 Austrian traditional herbal drugs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 149, 750–771 (2013).

Mansour, K. A., El-Mahis, A. A. & Farag, M. A. Headspace aroma and secondary metabolites profiling in 3 Pelargonium taxa using a multiplex approach of SPME-GC/MS and high resolution-UPLC/MS/MS coupled to chemometrics. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 105, 1012–1024. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.13892 (2025).

Edoga, C., Ejo, J., Anukwuorji, C., Ani, C. & Izundu, M. Antioxidant effects of mixed doses of vitamins B12 and E on male Wistar albino rats infected with trypanosoma brucei brucei. Immunol. Infect. Dis. 8, 7–13 (2020).

Eskander, J. Y., Haggag, E. G., El-Gindi, M. R. & Mohamedy, M. M. A novel saponin from Manilkara Hexandra seeds and anti-inflammatory activity. Med. Chem. Res. 23, 717–724 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. A UPLC-MS method for simultaneous determination of Geniposidic acid, two lignans and phenolics in rat plasma and its application to Pharmacokinetic studies of Eucommia ulmoides extract in rats. Eur. J. Drug Metabolism Pharmacokinet. 41, 595–603 (2016).

Schiano, E. et al. Validation of an LC-MS/MS Method for the Determination of Abscisic Acid Concentration in a Real-World Setting. Foods 12, 1077 (2023).

Resida, E., Kholifah, S. & Roza, R. Chemotaxonomic study of Sumatran wild mangoes (Mangifera spp.) based on liquid chromatography mass-spectrometry (LC-MS). SABRAO J. Breed. Genetics 53 (2021).

Baky, M. H., Kamal, I. M., Wessjohann, L. A. & Farag, M. A. Assessment of metabolome diversity in black and white pepper in response to autoclaving using MS-and NMR-based metabolomics and in relation to its remote and direct antimicrobial effects against food-borne pathogens. RSC Adv. 14, 10799–10813 (2024).

Su, C. & Oliw, E. H. Manganese lipoxygenase: purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13072–13079 (1998).

Porzel, A., Farag, M. A., Mülbradt, J. & Wessjohann, L. A. Metabolite profiling and fingerprinting of Hypericum species: a comparison of MS and NMR metabolomics. Metabolomics 10, 574–588 (2014).

Stolarczyk, M., Naruszewicz, M. & Kiss, A. K. Extracts from Epilobium sp. herbs induce apoptosis in human hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 65, 1044–1054 (2013).

Kwon, R. H. et al. Comprehensive profiling of phenolic compounds and triterpenoid saponins from Acanthopanax senticosus and their antioxidant, α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. Sci. Rep. 14, 26330 (2024).

Abd Elkarim, A. S. & Taie, H. A. Characterization of flavonoids from Combretum indicum L. Growing in Egypt as antioxidant and antitumor agents. Egypt. J. Chem. 66, 1519–1543 (2023).

Serag, A., Baky, M. H., Döll, S. & Farag, M. A. UHPLC-MS metabolome based classification of umbelliferous fruit taxa: a prospect for phyto-equivalency of its different accessions and in response to roasting. RSC Adv. 10, 76–85 (2020).

Chang, Z. et al. Tannins in Terminalia bellirica inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma growth by regulating EGFR-signaling and tumor immunity. Food Function. 12, 3720–3739 (2021).

Felegyi-Tóth, C. A. et al. Isolation and quantification of diarylheptanoids from European Hornbeam (Carpinus Betulus L.) and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS characterization of its antioxidative phenolics. Ournal Pharm. Biomedical Anal. 210, 114554 (2022).

Tang, K. S., Konczak, I. & Zhao, J. Phenolic compounds of the Australian native herb prostanthera rotundifolia and their biological activities. Food Chem. 233, 530–539 (2017).

Olennikov, D. N. & Chirikova, N. K. Phenolic compounds of six unexplored Asteraceae species from asia: comparison of wild and cultivated plants. Horticulturae 10, 486 (2024).

Karale, P., Dhawale, S., Karale, M. H. R. L. C. M. S. & Analysis Antihyperlipidemic effect of ethanolic leaf extract of Momordica charantia L. Hacettepe Univ. J. Fac. Pharm. 42, 93–104 (2022).

Tie, F. et al. Optimized extraction, enrichment, identification and hypoglycemic effects of triterpenoid acids from Hippophae rhamnoides L pomace. Food Chem. 457, 140143 (2024).

Kim, M. O. et al. Metabolomics approach to identify the active substances influencing the antidiabetic activity of Lagerstroemia species. J. Funct. Foods. 64, 103684 (2020).

Kuang, Y., Li, B., Wang, Z., Qiao, X. & Ye, M. Terpenoids from the medicinal mushroom antrodia camphorata: chemistry and medicinal potential. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38, 83–102 (2021).

Środa-Pomianek, K. et al. Pretreatment of melanoma cells with aqueous ethanol extract from Madhuca longifolia bark strongly potentiates the activity of a low dose of Dacarbazine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 7220 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Analysis of biologically active constituents in Centella asiatica by microwave-assisted extraction combined with. LC–MS Chromatographia. 70, 431–438 (2009).

Hu, W., Pan, X., Abbas, H. M. K., Li, F. & Dong, W. Metabolites contributing to rhizoctonia Solani AG-1-IA maturation and sclerotial differentiation revealed by UPLC-QTOF-MS metabolomics. PLoS One. 12, e0177464 (2017).

Pham, H. N. et al. UHPLC-Q‐TOF‐MS/MS dereplication to identify chemical constituents of Hedera helix leaves in Vietnam. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 1167265 (2022). (2022).

Lu, L. et al. Differential compounds of licorice before and after honey roasted and anti-arrhythmia mechanism via LC-MS/MS and network Pharmacology analysis. J. Liquid Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 46, 1–11 (2023).

Hanaki, M., Murakami, K., Gunji, H. & Irie, K. Activity-differential search for amyloid-β aggregation inhibitors using LC-MS combined with principal component analysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 61, 128613 (2022).

Alenezi, S. S. et al. The antiprotozoal activity of Papua new Guinea propolis and its triterpenes. Molecules 27, 1622 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Mohamed Ali Farag, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University for his efforts in facilitating UPLC-HRMS/MS analysis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EMS; Data curation, Investigation, Writing original manuscript, MHB; Conceptualization, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. RH; plant identification and collection, Investigation. MRE; Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The plant was botanically identified by Prof. Dr. Rim Hamdy, Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt. A voucher specimen has been deposited at Pharmacognosy Department, Faculty of Pharmacy, Egyptian Russian university, Egypt No = Lus2/2024.

Plant ethics

The methods in plant collection and experimentation were carried out in accordance with the guidelines prescribed by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists and adopted by the institutional research committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shawky, E.M., Hamdy, R., Elgindi, M.R. et al. UPLC-HRMS-MS profiling of Ludwigia adscendens subsp. diffusa aerial parts and investigation of the anti-inflammatory effect. Sci Rep 15, 19718 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05183-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05183-x