Abstract

The inventive idea of using Bentonite Nano-Clay spray as a Nano-Pico Spray (NPS) technique is an effective solution to the problem of erosion of historical brick monuments. This research focuses on protecting and restoring brick structures using bentonite nanoparticles as a Nano Soil Improvement (NSI) technique minimally invasive Nano-Spray to enhance mortar durability. By applying a protective Nano-Clay coating as a Green and Sustainable Spray (GSS) technique, rain and frost penetration into mortar layers significantly reduced. Various concentrations of nano-bentonite (2–10%) as a Green and Sustainable Soil Improvement (GSSI) technique with ethanol solvent were tested, with two applications of a 4% solution yielding optimal results. Validation through field emission scanning electron microscopy imaging (FESEM/SEM), X-Ray diffraction and Fluorescence analyses (XRD/XRF), Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET), porosity tests, water absorption time measurement, and weathering tests confirmed the efficacy and long-term stability of this method. Accelerated aging tests also demonstrated long-term stability and effectiveness, making this method a viable protective approach for historic brick structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mud and earthen structures represent some of the earliest forms of human-built environments, offering affordable, sustainable housing solutions across diverse climates. Despite their durability, these materials are prone to weather-related degradation, primarily due to moisture, erosion, and temperature fluctuations. Today, approximately 30–40% of the global population resides in earthen buildings, underscoring the importance of preserving these structures, many of which hold cultural and historical significance. The risk of degradation in these buildings arises from the unique composition of earthen materials and their vulnerability to environmental stressors like precipitation, salinity, and temperature-induced expansion and contraction1,2,3.

Enhancing soil properties to improve mechanical strength, minimize volume changes from water infiltration, and increase resistance to erosion caused by snow, rain, and wind can be achieved through three stabilization methods. These include mechanical stabilization, which involves compressing the soil to alter its mechanical parameters; physical stabilization, where the soil’s characteristics and texture are modified by incorporating materials like fibers; and chemical stabilization, which involves adding substances such as lime, bitumen, or other chemicals4,5.

Brick, a widely used material throughout history, has played a significant role in the construction of numerous historic buildings. Its adaptability has enabled the development of diverse structural elements such as domes, arches, and vaults6. Analyzing and studying historic brick and clay heritage reveals a growing global focus within the scientific community on their preservation and protection. This necessitates a thorough examination of these structures, including their materials, construction techniques, and vulnerabilities7. In Iran, the unique characteristics of adobe and brick historical buildings -such as high surface porosity, low strength, and susceptibility to climatic conditions-have drawn significant attention from Iranian researchers, who prioritize the preservation of these monuments8,9,10,11,12,13.

Building materials are inherently non-homogeneous, and factors such as environmental pollution and weathering, particularly in historical structures, lead to alterations in their composition. These changes often manifest as surface damage, especially at the junctions where the materials connect with mortar14,15. Mortar plays a crucial role in binding and connecting building components. It has been used since ancient times in the civilizations of Iran, Mesopotamia, and Egypt. Plaster, the first adhesive material utilized by humans, served as a coating, plastering, and mortar in various construction applications16.

The strength and durability of mortar are influenced by factors such as location, environmental conditions, climate, and the type of building17. For example, aerobic mortars (first category), when exposed to moisture, undergo transformation. If coated, they may collapse, or if used between layers, structural defects may develop, ultimately compromising the buildings integrity-examples include clay and plaster mortars. On the other hand, Hydraulic mortars (second category), used in dry environments, are prone to cracking under heat, which can cause structural separation and displacement over time, as seen in lime mortars18.

Moisture is a major cause of mortar degradation, manifesting as spillage, damage from rain, moisture retention, or fluctuating humidity levels. Additives have traditionally been used to improve mortar quality and strength. Mixed mortars may contain materials like quicklime, sand, volcanic ash, rock salts, baked clay, or bricks, with lime serving as the primary adhesive element19,20. To enhance mortar properties, traditional additives such as blood, eggs, fig juice, pig fat, and manure were commonly used. Over time, these have evolved to include modern additives like industrial by-products (e.g., fly ash, blast furnace slag) or advanced materials (e.g., organic polymers, acrylic and epoxy resins)21. The systematic study of ancient mortars is relatively recent. In 1981, ICCROM introduced a research strategy focused on ancient mortar analysis and repair. Understanding the composition and structure of mortars is vital for designing effective preservation and restoration methods tailored to specific destructive factors22. Accurate evaluation and diagnosis are critical for determining the appropriate conservation measures. This requires a scientific understanding of building behavior, material properties, and the application of researched methodologies19. Modern technology has significantly advanced conservation science by enhancing the understanding of materials and structures, developing preservation techniques, and producing protective products. This technological evolution has transformed approaches to restoring artworks and monuments and has extended to the protection of historical buildings and the management of heritage and rural areas23.

Over the past two decades, nanotechnology has advanced significantly, evolving into both a specialized discipline and an interdisciplinary field. In geotechnical engineering, nano soil improvement has emerged as an innovative approach that leverages nanomaterials to enhance soil properties24. –25.

Today, advancements in nanotechnology are providing more efficient methods for preserving and treating historical monuments, relying on the knowledge and ingenuity of experts in the field. Optimizing materials and restoration techniques through nanotechnology has become increasingly vital in safeguarding cultural and historical heritage. Although nanotechnology is considered a modern innovation, its application to historical artifacts has ancient roots. Archaeological discoveries reveal that nanoparticles were utilized in art and artifacts as early as the pre-Christian era. Researchers can now trace the presence of these nanoparticles in ancient man-made works, demonstrating their historical significance26. The aim of studying nanoscale materials is to develop highly functional and efficient new materials27.

In the past decade, the use of nanomaterials as reinforcing agents in organic coatings has grown substantially. The high surface-to-volume ratio of nanoparticles enables the production of organic coatings with remarkable performance28. Additionally, research on using nanoparticles to stabilize soil and improve construction materials has expanded. Studies indicate that incorporating nanoparticles into soil enhances its geotechnical properties29.

Nanoclays are among the most commercially utilized nanomaterials. These nanoparticles, derived from filtered clay powders, exhibit properties such as increased strength, heat resistance, and UV protection due to their high aspect ratio30,31. Combining nanoclays with other nanomaterials produces distinct effects on soil behavior, especially in collapse-prone conditions32.

Bentonite, a geological term often associated with industrial material, primarily comprises montmorillonite clay along with other minerals such as cristobalite, quartz, and feldspar. Its classification depends on the dominant exchange cations in the clay structure, leading to terms like sodium and calcium bentonites, or expanding and non-expanding clays33,34. Bentonite nanoparticles are particularly useful due to their adhesive and filling properties. They can penetrate and seal cracks and act as a filling material in nanocomposites35. When used as a natural pozzolan in partial replacement of Portland cement (e.g., at 2%, 4%, or 6% doses), nano-bentonite enhances mortar compressive strength. However, exceeding optimal doses may reduce strength. Additionally, using 2% nano-bentonite can improve mortar without significantly enhancing steel corrosion resistance36.

In lime mortars, bentonite slows carbonation during early curing stages, preventing crack formation and allowing continuous hardening. Tests show that replacing 5% of lime with natural bentonite achieves the best results for restoring historical adobe structures37. Replacing 30% of bentonite in concrete reduces water absorption, enhances compressive strength, and improves sulfate resistance, achieving up to 79% efficiency38.

Periodic interventions are crucial to strengthening and extending the lifespan of historical masonry structures. Such treatments must be reversible, non-invasive, compatible, and stable to preserve the structure’s historical identity and integrity39.

Retrofitting methods for historical monuments are generally categorized into maintenance, protection, reconstruction, and restoration40. Choosing an appropriate intervention method for any historical structure is often a complex and challenging task. This complexity arises from a lack of comprehensive information about the structure, including its architectural and structural features, geometric data, material composition, construction techniques, and methods for addressing its specific needs41. In response to these challenges, and with increasing competition to develop innovative and compatible preservation techniques, research has focused on creating multi-purpose coatings for historical monument surfaces. These coatings aim to minimize intervention while enhancing the durability of traditional materials and reducing costs. Nanotechnology has emerged as a promising approach to preventing or mitigating harmful factors affecting cultural heritage42.

Despite extensive research on the applications of nanoparticles, particularly nanoclays, in soil stabilization, their use as a spray for protecting and strengthening the mortar between bricks in historical buildings has not yet been explored. Given the limited studies on the preservation of mortar in historical brick structures and the abundance of such buildings, there is a pressing need for localized research tailored to different climatic conditions to address these preservation challenges effectively.

This research aims to address this gap by exploring the use of bentonite nanoparticles in a nanospray application to reinforce mortar surfaces. Different concentrations of nano-bentonite (2–10%) were tested with ethanol as a solvent, and the efficacy of multiple spray coatings was evaluated. SEM imaging, BET porosity analysis, surface water absorption, rain simulation, and frost resistance tests were conducted to assess performance. Results indicate that a 4% nano-bentonite solution applied in two coats optimally fills pores, reduces water absorption, and significantly improves resistance to weathering factors. By investigating locally sourced ingredients and tailoring the nanospray application for specific climatic conditions, this research contributes to the development of sustainable and effective preservation techniques for earthen heritage structures.

Test materials and methods

Materials

Examples of mortar analyzed in this research come from the historic Kashaneh Bastam Tower, located in Semnan Province, Iran. This brick structure is a significant architectural masterpiece from the Ilkhanid period, constructed in 700 AH. The decorative tested mortars were extracted from between the bricks on the tower’s facade. These samples measured 4 × 4 × 6 cm. Following collection, the samples were trimmed to meet testing size requirements, cleaned with a soft brush, and treated with 96% neutral ethyl alcohol before classification for testing.

The bentonite nanoclay used in this research, branded as “NanoClay, Swelling Bentonite,” was produced by the NRG research group in Iran. It has a density of 0.8 g/cm³ and a particle size of 1–2 nm. The chemical composition of the nanoclay, as determined by XRF analysis, is presented in Table 1. SEM imaging confirmed the nano-scale particle size, with a representative image at 500 nm magnification shown in Fig. 1.

Preparation of samples

To determine the optimal concentration of bentonite nanoclay for spraying, solutions containing 2%, 4%, 6%, and 10% nanoclay by weight in 100 ml ethanol were prepared. Each solution was sonicated in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min. The application and testing involved two phases:

First phase

In this phase, different nanoclay concentrations were sprayed onto one surface of each mortar sample. The surface area was calculated to ensure precise application, with approximately 175 square centimeters covered by 100 ml of solution. The values were chosen to compare particle penetration and surface coverage effectively. Ethanol was selected as the solvent due to its low absorption and resistance to washing.

Second phase

Once the optimal nanoclay concentration was determined using FE-SEM results, the spraying process was repeated to refine application methods. Two approaches were tested:

-

1.

Single-step spraying using the optimal concentration.

-

2.

Two-step spraying using the same concentration.

The results from both methods were compared to evaluate their effectiveness in improving mortar conditions.

Finally, samples were prepared in adequate dimensions and quantities for further analysis. These samples were divided into two groups, A and B, and tested with five formulations:

-

1.

Control sample without spray.

-

2.

2% nanoclay (NB2).

-

3.

4% nanoclay (NB4).

-

4.

6% nanoclay (NB6).

-

5.

10% nanoclay (NB10).

These samples, along with the testing setup, are shown in Fig. 2.

Tests

FESEM/SEM Electron Microscope Test: The optimal percentage of nanoclay was determined by comparing the hole-filling rate in all samples using the FESEM/SEM MIRA3 device. The test involved preparing samples with dimensions smaller than 1 cm². The porosity was also analyzed using the BET method with the Mini II device. This method measures surface area without damaging the samples by using nitrogen gas. The mortar samples were tested before and after spraying with the nanoclay. For this test the sample dimensions were prepared with a maximum of 0.4*0.4*0.3 Cm.

XRD, XRF, and ICP-OES Tests: For X-ray Diffraction (XRD), X-ray Fluorescence (XRF), and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES), the samples were powdered and used in quantities of several grams for each test. XRD (Ultima IV device model) was employed to identify and qualitatively analyze the minerals present in the nanoclay. XRF (X’Pert-Pro-MPD model) detected the elements and oxides in the bentonite nanoclay, quantifying their weight percentages as per ASTM E 1621-13 standards. ICP-OES (ARCOS FHS12 model) served as an alternative to XRF for trace element detection, following the NIST SRM 31 Series reference standards.

Static Contact Angle Measurement: The static contact angle measurement test, conducted with a Jikan CAG-20 model device (sample dimensions 1 × 1 × 2 cm), measured water absorption. A drop of distilled water (4 µl) was placed on the sample, and the contact angle was calculated by observing the three-phase line where the water met the surface using a high-precision camera. The test was repeated 3 to 5 times at ambient temperature, and the average value was determined.

Erosion Resistance: To evaluate mortar durability against rainfall, a rain simulator generated drops without pressure. This test aimed to simulate erosion under artificial rainfall:

-

The simulator’s average rainfall height was 55 cm, with an average raindrop diameter of 4.8 mm and a drop frequency of 11%.

-

Pre-test, the sample weights were recorded after drying at 50 °C for 4 h.

-

During the test, samples (plaster mortar) were subjected to 30 drops per minute for 16 h under two rain intervals, followed by drying at 60 °C for 4 h.

-

The loss of solid material due to erosion was compared to the initial dry weight, and the samples were then analyzed using FE-SEM.

Frost Resistance: In light of the semi-arid and cold region where the monument is located, a freezing test was conducted to simulate the destructive mechanism caused by frost:

-

The samples were subjected to artificial rainfall for 30 min, followed by freezing at -10 °C for 4 h, and then drying at 60 °C for 4 h.

-

The evaluation of the samples occurred after each freezing cycle. Samples were further analyzed using FE-SEM.

Accelerated Aging Test: To assess the long-term behavior of the coating against corrosion and evaluate the durability of clay nanoparticles, an accelerated aging test was conducted. The test simulated the environmental conditions of the historical monument, subjecting the samples to rapid changes in temperature and humidity:

-

The aging cycle involved four stages with varying temperature and humidity intensities, lasting 12 h per cycle for 40 intervals (totaling 480 h).

-

Coated and control samples were exposed to water vapor and humidity during each cycle to mimic the effects of seasonal climatic changes on the mortar.

These comprehensive tests provided critical insights into the effectiveness of nanoclay in enhancing the durability and preservation of historical mortar.

Discussion

Recognition of historical mortar

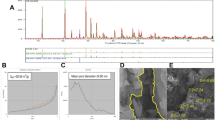

Figure 3 illustrates the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the historical mortar. The analysis reveals the presence of quartz and gypsum in the sample, with the gypsum phase being the dominant component. The detected phases indicate that gypsum is the major constituent of the mortar, while quartz is present in smaller amounts.

-

1.

Quartz: Low SiO2.

-

2.

Gypsum: H4Ca1O6S1.

The XRD analysis indicates that the mortar contains both silica and calcium sulfate, with the largest proportions attributed to oxygen, sulfur, and calcium for calcium sulfate, and silicon and oxygen for silica.

In Fig. 4, A displays the nitrogen adsorption and desorption curve (BET), while B presents the pore size distribution (BJH) for the historical mortar sample. The results indicate a surface area of 18.57 square meters per gram, a pore volume of 0.064 cubic centimeters per gram, and an average pore size of 14.00 nm. The pore size distribution curve indicates that most pores are smaller than 1.85 nm.

Figure 5, obtained from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the mortar sample, reveals the presence of pores and a porous surface, suggesting surface erosion of the mortar. Image A, magnified at 5 micrometers, and image B, magnified at 20 micrometers, show that the distance between cracks and voids ranges from 1.53 to 7.24 micrometers.

Covering historic mortar with nanoclay

In this research, various tests were conducted on the durability of the coated mortar sample compared to the raw mortar (control). We will review them below:

SEM scanning electron microscope images

Various concentrations of bentonite nano clay solution were applied to the primary mortar samples with specific surface areas, as shown in Table 2. To identify the optimal nanoclay percentage based on hole filling, SEM images of the sprayed mortar samples were taken. Figure 6 displays the images of both control and sprayed mortar samples with 2%, 4%, 6%, and 10% nanoclay concentrations, while Fig. 7 displays the SEM images of the mortars. Figure 6 visually demonstrates the impact of applying a bentonite nanoclay layer to the mortar surface compared to the control sample. The comparison reveals that in image A (control sample), the mortar surface shows corrosion and minor cracks. In image B, with a 2% nanoclay solution, fine cracks remain visible on some areas of the surface. In image C, a 4% nanoclay solution applied in a single spraying step shows minimal cracks. In image D, the 4% nanoclay sprayed in two stages results in a smooth, crack-free surface. In image E, a 6% nanoclay coating makes cracks harder to detect, but some areas show a buildup of nanoclay. In image F, a 10% nanoclay spray causes the formation of new, finer cracks due to an excessive nanoclay coating, indicating that higher percentages should be avoided.

Images of control and sprayed mortar samples. The control sample of the mortar surface (A), covered with a 2% solution of nanoclay (B), a sample solution with 4% nanoclay in one spraying step (C), the sample sprayed with 4% nanoclay solution in two spraying stages (D), covered with a 6% solution of nanoclay (E), covered with a 10% solution of nanoclay (F).

Comparing the SEM images of the sprayed samples (Fig. 7) with the control sample (Fig. 5) shows that in image A, the uniform nanoclay coating still has cracks with a gap of less than 2.57 micrometers at 20x magnification, and these cracks are not completely filled. As a result, the 2% nanoclay solution (NB2) was discarded for further testing. In image D, the 6% nanoclay solution (NB6) shows empty spaces under 0.94 micrometers, making the cracks difficult to detect, but the uneven surface due to nanoclay accumulation is noticeable. This percentage of nanoclay is not ideal for filling cracks and holes in the mortar. In image E, the 10% nanoclay solution (NB10) creates gaps that lead to new cracks, making it unsuitable for the application.

To refine these results, microscopic images A and B from Fig. 8, showing the one-stage and two-stage spray samples at 1-micrometer magnification, demonstrate that the two-stage application of the 4% nanoclay solution results in better penetration of the particles. This allows for more thorough filling of cracks and holes, leading to a more effective and complete surface coating. Consequently, spraying with 4% bentonite nanoclay in two stages was selected as the optimal solution (opt).

Determination of surface water absorption by contact angle measurement test

Table 3 presents the water absorption times for the control sample and the sprayed samples, showing a reduction in water absorption for the samples treated with both spray methods: 4% nanoclay in a single application (NB4-1) and 4% nanoclay in two applications (NB4-2). The results confirm that the two-step spray method, which applied nanoclay in two stages, provided better performance and ensured the correct choice of the optimal nanoclay percentage.

Porosity determination by BET method

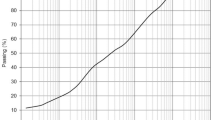

For the sample treated with the optimal 4% nanoclay solution (NB4-2), the BET analysis reveals a surface area of 18.57 m²/g, whole volume of 0.064 cm³/g, and an average hole size of 13.37 nm. The BJH curve indicates that most of the holes are smaller than 1.2 nm. Comparing the BJH and BET curves of the control and sprayed samples (Figs. 4 and 9) shows that although the Nanoclay treatment filled the holes, it also increased the porosity slightly. This increase in porosity can be attributed to the filling of the very fine holes on the mortar surface with nanoclay.

Impact of nano spray on precipitation in rain simulator test

Table 4 shows the weights of the control mortar sample and the NB4-2 nanoclay-treated sample, both before and after the rain simulator test. SEM images were then taken, and from the observations based on Table 3, it was found that the nanoclay-sprayed sample exhibited less erosion compared to the control sample. Furthermore, by comparing image A10, it is evident that after the rain simulator test, the control mortar sample showed an increase in crack size when compared to its condition before the test (Fig. 5), with the crack distance now being less than 11.08 micrometers. In Fig. 10, the mortar sample treated with the optimal 4% NB4-2 nanoclay solution after the rain simulator test, under 20x magnification, is seen to retain its uniform and consistent surface. Although the cracks have changed compared to the pre-test condition (Fig. 7), the distance between the cracks is reduced to under 4.13 micrometers. Despite an overall increase in crack size and void distances for both mortar samples after the test, the nanoclay-treated sample shows more favorable conditions than the control sample, demonstrating better performance and meeting the goals of this research.

Effect of nano spray on freezing resistance after Frost resistance test

Upon checking the weight of the samples before and after the frost resistance test, the erosion levels resulting from the test, as presented in Table 5, yielded the following outcomes: The sample treated with NB4-2 nanoclay showed a lower erosion rate compared to the control sample. To further analyze this, microscopic images were taken and the structure of the particles was examined, alongside the effect of the optimal percentage of bentonite nanoclay solution on cracks and voids caused by erosion on the samples’ surfaces before and after the frost resistance test. The results were compared to the control sample: In Fig. 11, FE-SEM images of the control sample (at a 20-micrometer magnification) reveal the presence of holes and a porous surface. After the frost resistance test, as seen in Image B5, the texture and size of the cracks changed, with the distance between the cracks reported to be less than 20.20 micrometers. Figure 11 shows the mortar sample treated with the optimal percentage of NB4-2 nanoclay solution after the frost resistance test, also at a 20-micrometer magnification. Although the surface has changed compared to Image C7 (the pre-test state of the sample), the surface coverage remains intact and uniform, and the cracks have altered, with the distance between the cracks now reduced to less than 4.07 micrometers. Based on the comparison of these samples before and after the frost resistance test, it can be concluded that, although there is an incremental increase in the size of cracks and the distance between voids in both mortar samples, the nanoclay-treated samples demonstrate better performance and conditions than the control sample, fulfilling the objectives of this research more effectively.

Effect of Nano Spray on Samples after Accelerated Aging Test.

In this test, both the control sample and the optimal NB4-2 nanoclay-treated sample underwent 40 alternating cold-heat cycles for 480 h. Microscopic images were taken at a 20-micrometer magnification (as shown in Fig. 12) of both the control mortar sample and the nanoclay-treated sample after the accelerated aging test. As shown in Image A, after the aging test, the texture and size of the cracks had changed in comparison to the control sample before the test (Image B5). The distance between the cracks was measured to be less than 11.65 micrometers. In Image B, after the aging test, the nanoclay-treated mortar sample still exhibited a uniform and coherent surface, with the nanoclay coating intact. However, the size of the cracks had altered in comparison to the control sample before this test (image C7), and the distance between the cracks had decreased to less than 1.29 micrometers. Thus, based on the findings aligned with the research objectives, the nanoclay-treated sample displayed better performance and cohesion compared to the control sample in this experiment.

Conclusion

This research examines the impact of strengthening and protecting mortar between historical bricks using bentonite clay nanoparticles. The evaluation is based on results from various tests, including FE-SEM, BET porosity measurement, contact angle measurement, rain simulator, frost resistance, and accelerated aging tests.

-

The FE-SEM and BET test images reveal that the bentonite nanoparticle spray effectively penetrates the mortar’s voids, filling them and forming a consistent and cohesive layer on the mortar surface.

-

In evaluating the resistance of mortars sprayed with nanoparticles against moisture and surface water absorption, the results indicate a noticeable reduction in water absorption.

-

Upon examining and comparing the coverage of bentonite nanoclay solution at the optimal percentage and its influence on cracks and voids resulting from erosion, it was concluded that the NB4-2 nanobentonite sample demonstrated a better performance than the NB4-1 nanobentonite sample across all tests, making it a more suitable option for building applications.

-

The comparison of images from FESEM and BET tests shows that the bentonite clay nanoparticles spray has reduced the pore size by filling the voids and creating a uniform surface layer. When applied as a 4% solution in two sprays, the nanoparticles effectively fill the voids, enhancing the mortar’s strength between bricks.

-

In comparison to traditional and modern methods of mortar reinforcement, nanospray technology offers a faster alternative. Additionally, it utilizes natural materials, aligning with the core composition of the mortar, which ensures compliance with cultural heritage and historical building preservation guidelines.

-

This research demonstrates that spraying bentonite clay nanoparticles is an efficient technique for reinforcing and protecting historical mortars. It helps reduce erosion, prevents excessive absorption of surface water from rain and snow, and contributes to the extended lifespan of historic buildings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wolfskill, L. A., Dunlap, W. A. & Gallaway, B. M. Handbook for Building Homes of Earth, Translated by tabesh, H. Institute of University Publication, Tehran, Iran (1987).

Lorenzo, M., Urs, M. & Patrick, F. Mechanical behaviour of Earthen materials: A comparison between Earth block masonry, rammed Earth and cob. Constr. Build. Mater. 61, 327–339 (2014).

CRATERRE BUILDING CULTURE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT,http://craterre.org/enseignement?new_lang=en_GB

Houben, H., Balderrama, A. A. & Simon, S. Our earthen architectural heritage: materials research and conservation. MRS Bull. 29 (5), 338–341 (2004).

Xue, Q., Lu, H. J., Li, Z. Z. & Liu, L. Cracking, water permeability and deformation of compacted clay liners improved by straw fiber. Eng. Geol. 178, 82–90 (2014).

Niroumand, H., Zain, M. F. M. & Jamil, M. Var. Types Earth Build. Social Behav. Sci. 89 226–230 (2013).

Silveira, D., Varum, H., Costa, A. & Neto, C. Survey of the facade walls of existing Adobe buildings. Int. J. Architectural Herit. 10 (7), 867–886 (2016).

Zabihi, S. Pathology of brick-made decoration of chahar bagh school of Isfahan, MSc Thesis, Art University of Isfahan, Iran (1997).

Nejad, A. S. Sh. Investigation of paraloid as adhesive and consolidant material at climatic conditions of Iran, MSc Thesis, Art University of Isfahan, Iran (1998).

Khakban, M. The examination of renovation materials for application in historic work conservation in guilan region, MSc Thesis, Art University of Isfahan, Iran (1997).

Bater, M., Abed Esfehani, A. & Paidar, H. Structural studies of Haft tappeh’s cuneiform tablets. Iran. J. Cryst. Mineral. 13, 155–166 (2005).

Vahidzadeh, R. The examination of glaze decorative production process related to architectural middle elam and analysis of its damages, MSc Thesis, Art University of Isfahan, Iran (2005).

Sadat-Shojai, M. & Ershad-langroudi, A. Polymeric coatings for protection of historic monuments: opportunities & challenges. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 112, 2535–2551 (2009).

Honeyborne, D. B. Weathering and Decay of Masonry, Conservation of Building and Decorative Stone, v.1, Edited by J. Ashurst and F.G. Dimes, Butterworth-Heinemann Series in Conservation and Museology, London (1990).

Amoroso, G. G. & Fassina, V. Stone Decay and Conservationpp.453 (Elsevier, 1983).

Naeijpour, T. & Farshad, M. History of engineering in Iran, pp.512 (2011).

Mokhtarian, A. Pathology and Restoration of Historical Buildings (Parsia, 2017).

Zomorshidi, H. Traditional Materials Science (Zomorod, iran, 2002).

Hadian-Dehkordi Use of Laboratory Researches in Conservation and Restoration of Historical Buildings (Tehran University, Tehran, Iran, 2007).

Bayraktar, A. Analysis of historical monuments and seismic retrofitting methods, Translated by Nezhatzadeh, S. Publications of the Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism (2013).

Palomo, A., Blanco-Varela, M. T., Martinez-Ramirez, S., Puertas, F. & Fortes, C. Historic mortars: characterization and durability, Spain. (2002).

Palomo, A., Blanco-Varela, M. T., Martinez-Ramirez, S., Puertas, F. & Fortes, C. Historic mortars: characterization and durability. New tendencies for research. In Advanced Research Centre for Cultural Heritage Interdisciplinary Projects, Fifth Framework Programme Workshop (2002).

Jukilehto, J. A history of architectural conservation,)2017(.

Changizi, F. & Hadad, A. Effect of Nano-SiO2 on the Geotechnical Properties of Cohesive Soil (Springer, 2015).

Niroumand, H., Balachowski, L. & Parviz, R. Nano soil improvement technique using cement. Sci. Rep. 13, 10724 (2023).

Bagherpour, M., Doroudi, M. & Majzoubhosseini, S. Application of nanotechnology in the conservation and restoration of works of art. (2005).

Zahedi, M., Sharifpour, M., Jahanbakhshi, F. & Bayat, R. Nanoclay performance on resistance of clay under freezing cycles. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. p: 427–434. (2014).

HuaWu, Z. & Shen Sh. Jian, Chemical Reviews. vol 109, pp. 3893–3957. (2008).

GHasabkolaei, N., CHoobbasti, J., Roshan, A. & Ghasemi, N. Geotechnical properties of the soils modified with nanomaterials: A comprehensive review. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 17, 639–650 (2017).

Ouhadi, V. R., Amiri, M., Amirkabir, J. & Civil Geo-environmental Behaviour of Nanoclays in Interaction with Heavy Metals Contaminant, 42, 3, pp 29–36. (2011).

Melo, J. V. S. & Trichês, G. Effects of organophilic nanoclay on the rheological behavior and performance leading to permanent deformation of asphalt mixtures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 28 (11), 04016142 (2016).

Iranpour, B. & haddad, A. The influence of Nano-materials on collapsible soil treatment, Engineering Geology (2016).

Inglethorpe, S. D. J., Morgan, D. J., Highley, D. E. & Bloodworth, A. J. Thchinal reportwg/93/20. Mineralogy and Petrology Series. Br. Geol. Surv. 1–115. (1993).

Adamis, Z., Williams, R. B., Bentonite, kaolin, and selected clay minerals. Environmental. Health Criteria. World Health Organization Library, Vol. 231. Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, Geneve. (2005)

Bukit, N., Frida, E., Harahap, M. H. Preparation natural bentonite in Nano particle material as filler Nanocomposite high density polyethylene (Hdpe). Composites, 3, 13. (2013)

Karunarathne, V.K., Paul, S.C., Šavija, B. Development of nano-SiO2 and bentonite-based mortars forcorrosion protection of reinforcing steel. Materials, 12(16), 2622. (2019).

Andrejkovičová, S., Alves, C., Velosa, A. and Rocha, F. Bentonite as a natural additive for lime and lime–metakaolin mortars used for restoration of adobe buildings. Cement and Concrete Composites, 60, 99–110 (2015).

Ahmad, S., Barbhuiya, S.A., Elahi, A. and Iqbal, J. Effect of Pakistani bentonite on properties of mortar andconcrete. Clay Minerals, 46(1), 85–92 (2011)

The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments, Athens Conference, 21-30 October 1931.

Korkmaz, E., Vatan, M., Retrofitting Deniz Palace Historic Building for Reusing, International Journal of Electronics;Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering 2 (269-278).

Colonna, M., Gentilini, C., Pratico, F. & Ubertini, F. Surface Treatments for Historical Constructions UsingNanotechnology. Key Engineering Materials, 624, 313–321 (2014).

Quagliarini, E., Bondioli, F., Goffredo, G.B., Licciulli, A., Munafò, P. Self-cleaning materials on Architectural Heritage:Compatibility of photo-induced hydrophilicity of TiO2 coatings on stone surfaces, J of Cultural Heritage, 14, 1–7 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Financial support of these studies from Gdańsk University of Technology by the DEC- 1/1/2023/IDUB/I3b/Ag grant under the ARGENTUM - ‘Excellence Initiative - Research University’ program is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. J., S.R., H. N., M.A. , and L.B. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jalalifar, S., Niroumand, H., Afsharpour, M. et al. Bentonite nanoclay and spray techniques as a nano pico technology (NPT) for enhancing mortar in heritage and historical buildings. Sci Rep 15, 22450 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05189-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05189-5