Abstract

As compared to free-living microbes, host-associated (HA) microbes are unique in that they experience dispersal at both the microbial and host scales. This is particularly clear in systems where hosts experience strong barriers to dispersal, for example hosts that live in patchy habitats or metapopulations. In these systems, there are both limits to dispersal of HA microbes from host to host (microbial scale dispersal) and limits to dispersal of hosts from habitat patch to habitat patch (host scale dispersal). Few studies have considered how host and microbial scale dispersal limitation impacts spatial patterns in HA microbiota. We address this question using green salamander skin microbiota. This species exhibits population structure wherein animals primarily inhabit disjunct rock outcrops with occasional dispersal between outcrop populations. We find strong evidence for the importance of host scale dispersal based on differences in distance-decay of similarity between salamander and environmental microbiota. We find weaker evidence/mixed support for the importance of microbial scale dispersal based on low similarity of the host exclusive skin microbiota but a lack of dependence of skin microbiota similarity and diversity on host density. We discuss implications of our findings, both with reference to other processes governing HA microbiota assembly and with reference to amphibian conservation. For the latter, we consider variation in chytrid-inhibitory community profiles across populations and potential ramifications in terms of variation in susceptibility to chytridiomycosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macroscopic hosts benefit from the microbial communities that they harbor. Termed host-associated (HA) microbiota, these communities aid their hosts in myriad ways1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, for example by facilitating digestion10,11, producing defensive toxins12,13, or inhibiting pathogen colonization14,15,16. Because of the importance of HA microbiota to host success17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, hosts are thought to curate their HA microbiota through a combination of anatomical26, physiological26,27,28, and behavioral traits3. This allows hosts to retain beneficial microbes while inhibiting harmful ones from colonizing or dominating composition. The assumption that hosts preferentially select members of their microbiota has led to intense research on how host factors impact HA microbiota assembly. Numerous studies have considered the role of host traits like diet29, disease status30,31, age32,33,34,35, genetics36,37, trophic level38, and host size39. However, while many of these factors appear important, they all stem from the same basic paradigm – that HA microbiota assembly is governed by conditions on or in the host. This is tantamount to assuming that selection (i.e., environmental filtering) is the primary determinant of HA microbiota structure and composition.

Recently, studies have extended the selection paradigm to consider not only conditions on/in the host (‘microbial scale selection’), but also the broader environment where the host lives (‘host scale selection’). Studies have found, for example, that amphibian skin microbiota differ depending on whether the amphibian is found in a pond or a stream40. Studies have also found dramatic effects of captive41,42,43 and/or urban44 environments on HA microbiota. Meanwhile, a recent meta-analysis of 43 terrestrial and aquatic species showed that host environment (i.e., host scale selection) may be more important than host factors (i.e., microbial scale selection) in determining HA microbiota composition and structure45. While the extension from host factors to host environment emphasizes the multiscale nature of HA microbiota assembly, host environment and host factors still operate in the same manner, governing HA microbiota assembly through the process of selection.

Selection, however, is not the only process known to impact community assembly. In many ecological communities, three additional process - dispersal, drift and speciation46 – also contribute significantly. Historically overlooked, even in macroorganismal ecology, these three other processes can be equally important for understanding the structure and composition of ecological communities. While the impacts of speciation47,48,49 and drift50,51,52 on HA microbiota have been recently explored, the role of dispersal remains heavily understudied. One of the challenges of characterizing the effects of dispersal is that, like selection, dispersal can impact HA microbiota by operating at both the microbial (i.e., movement of microbes between hosts or from the environment to the host) and host (i.e., movement of hosts) scales. The importance of dispersal at these two distinct scales is only now starting to gain interest in HA microbiota literature53,54.

A clear starting point for examining how multiscale dispersal influences HA microbiota is to study systems where hosts exhibit patchy population structure. These are good systems because they create strong dispersal barriers, not only against host-to-host transfer of microbes (microbial scale dispersal), but also against host movement through the landscape (host scale dispersal)37. Amphibians are model organisms for these types of systems55,56,57 due to their poor dispersal ability, high site fidelity, and narrow habitat requirements, often dictated by moisture availability58,59,60. Ultimately, this means that many amphibian species are restricted to discrete habitat patches (e.g., ponds, rock outcrops, streams) and that successful dispersal between these patches is rare. This is particularly true for salamanders that are less mobile than frogs61.

Beyond patchy population structure, amphibians are ideal model systems for studying HA microbiota for a second reason: because of the well-known importance of amphibian skin microbes to pathogen defense. Since the 1980s, amphibians have experienced dramatic, global declines in abundance, as well as widespread extinctions, due to a skin disease known as chytridiomycosis. Caused by the fungal pathogens Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) and B. salamandrivorans (Bsal), chytridiomycosis has motivated significant research into the Chytrid-inhibitory properties of the amphibian skin microbiota. This has led to the creation of large databases characterizing the anti-Bd and anti-Bsal characteristics of thousands of microbial taxa16. As a result, these databases can be used to assess the putative extent to which multiscale dispersal impacts not only HA microbiota composition, but also, important functional consequences of the HA microbiota62. Further, the ongoing chytridiomycosis pandemic and the threat of Bsal reaching new amphibian hotspots, like the southeastern U.S., makes understanding the processes governing amphibian skin microbiota of paramount importance to amphibian conservation.

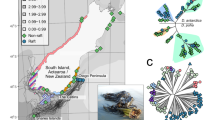

In this study, we used green salamanders, patchily distributed among rock outcrops in upstate South Carolina (see Fig. 1), to investigate how multiscale dispersal limitation interacts with the processes of microbial scale selection (filtering due to the skin environment) and drift (local microbial extinction) to determine spatial variation in salamander skin microbiota. In particular, we were interested in whether patterns of patch connectivity (host scale dispersal limitation) and/or host genetic distance (microbial scale selection) predicted microbiota similarity. We were also interested in whether local population-level characteristics like host population size (microbial scale drift), host density (microbial scale dispersal) and outcrop size (microbial scale drift and dispersal) had an impact on HA microbiota. Broadly speaking, we predicted that (1) host microbiota community similarity would be highest within local populations and (2) would decay with distance between local populations, reflecting increased barriers to host-scale dispersal. We also predicted that (3) HA microbiota α-diversity (diversity per salamander) would increase with the density of the local host population, reflecting decreased barriers to microbial scale dispersal (i.e., higher rates of host-host contact). Further, we predicted that (4) HA microbiota α-diversity would increase with the abundance of the local host population, reflecting decreased risk of microbial extinction63 (i.e., decreased drift). Finally, we predicted that (5) HA microbiota α-diversity would increase with the spatial extent of the rock outcrop housing the local host population, reflecting both decreased risk of microbial extinction63 (i.e., drift) and increased opportunity for dispersal of microbes from the environment to salamander skin (i.e., due to hosts moving over a larger rock surface and/or among more crevices).

Nine green salamander populations exhibiting metapopulation structure characterized by Novak70 distributed across upstate South Carolina.

Results

The most abundant phyla across salamander skin (see Fig. 2) were Proteobacteria (33.6%), Actinobacteriota (29.7%), Acidobacteriota (7.7%), Bacteroidota (7.5%), and Verrucomicrobiota (5.1%). The most abundant phyla across crevice swabs were Actinobacteria (31.3%), Proteobacteria (22.9%), Bacteroidota (11.9%), Acidobacteriota (7.6%), and Planctomycetota (7.2%). The most abundant genera across salamander skins were Kitasatospora (5.4%), Streptomyces (4.2%), Acidothermus (3.8%), Chlamydia (2.9%), and Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia (2.8%). The most abundant genera across crevice swabs (see Fig. 2) were Crossiella (6.2%), Dermacoccaceae (4.4%), Mycobacterium (3.3%), an uncultured Gemmataceae (2.8%), and Arachidicoccus (2.8%). In general, our results did not depend strongly on the microbial taxonomic level or the diversity metric chosen. Thus, in the main text we focus on results at the microbial amplicon sequence variant (ASV) level using phylogenetically agnostic incidence metrics (richness and Jaccard dissimilarity). We choose these metrics because our system features modest host dispersal limitation over relatively small distances, allowing for at least some movement of hosts between patches over ecological timescales. Consequently, we expect that the signature of dispersal limitation will be phylogenetically shallow and thus most likely to be detected using metrics that are sensitive to strain-level variation in microbiota composition. Results using abundance-based and/or phylogenetically aware metrics at the microbial ASV-level and all results at the genus level are reported in the SI. When not included in the main text, the SI also includes analyses with all environmental microbial taxa removed (ASV-ENV, i.e., the ‘salamander exclusive microbiota’).

Bar graphs showing the composition of each individual salamander skin sample, along with associated crevice swabs. Salamander skin swabs are grouped by local population from West to East. Bars show the relative abundance of the most abundant ASVs, classified to genus and colored by phylum for the most abundant (across all samples) phyla. Specifically, we use Proteobacteria (green), Actinobacteriota (orange), Acidobacteriota (blue), Planctomycetota (purple), and Bacteroidota (teal). All other phyla are collectively shown in grey.

Do salamander skin microbiota differ from crevice microbiota?

Green salamander skin microbiota contained both ASVs that were exclusive to salamanders (median: 51.1% of reads and 68.2% of ASVs) and ASVs that were shared with the environment (see Figure 3A, B). In general, microbial taxa that were abundant in the environment were more prevalent on salamanders (see Figure 3C). However, some abundant environmental microbes were absent from salamanders, while some rare environmental microbes were prevalent among salamanders. Consistent with the over- and under-representation of different microbial taxa in salamander versus crevice microbiota, ANCOM-BC2 identified one ASV that occurred at significantly greater relative abundance on salamanders and 16 ASVs that occurred at significantly greater relative abundances in crevices (see Figure 3D, ASVs labeled based on genus for biological interpretation). ANCOM-BC2 also identified 34 genera that occurred at significantly greater relative abundance on salamanders and 11 genera that occurred at significantly greater relative abundances in crevices (see SI Figure 1). Likewise, after correction for multiple comparisons, indicator species analysis identified seven ASVs that were significant indicators of salamander microbiota and 27 ASVs that were significant indicators of crevice microbiota (see Figure 3D, ASVs collapsed at genus-level for biological interpretation). Indicator species analysis also identified 19 genera that were significant indicators of salamander microbiota and 112 genera that were significant indicators of crevice microbiota (see SI Figure 2). While some of the genera identified by ANCOM-BC2 were the same as those identified by indicator species analysis (e.g., Bryocella, Mesorhizobium), others were sensitive to the method used (e.g., Massilia, Streptomyces). In keeping with the differences detected by ANCOM-BC2 and indicator species analysis, crevice and salamander microbiota differed significantly in composition (Jaccard PERMANOVA: p-value < 0.001; see Figure 4A). This was true for all metrics and microbial taxonomic scales considered (see SI Figure 3, SI Table 4). Interestingly, however, crevice and salamander skin microbiota did not differ significantly in α-diversity (ASV Richness: W = 757.5, p-value = 0.52; see Figure 4B). Again, this was true for all metrics and microbial taxonomic scales considered (see SI Figure 4).

Bar graphs showing the partitioning of salamander microbiota between taxa that are exclusive to salamanders (green) and taxa that are shared with the environment (grey) for both total microbial abundance (a) and total microbial ASVs. (c) Salamander occupancy for each microbial taxon (i.e., fraction of salamanders colonized) as a function of mean taxon relative abundance in crevice microbiota. The solid line shows predicted salamander occupancy based on a neutral model97 fitted using crevice occupancy and abundance, while the dotted and dashed lines show 95% and 99% confidence intervals respectively. Taxa are colored according to whether they are more (red), less (blue) or not different (black) from neutral model predictions based on the 99% confidence interval. (d) ANCOM-BC2 analysis of bacterial ASVs (labeled based on the genus that they map to); (d) indicator species analysis of bacterial ASVs (labeled based on the genus that they map to).

Do salamander skin microbiota differ across local populations?

Unlike differences between skin microbiota and crevice microbiota, neither ANCOM-BC2 nor indicator species analysis found many taxa that were differentially represented across salamander populations. ANCOM-BC2 found only one bacterial genus, Bryocella, that exhibited significant variation, with lower relative abundance at site 3688 compared to all other sites. Meanwhile, indicator species analyses found no significant ASV indicators, at least after correcting for multiple comparisons. Results were similar at the genus level and for the salamander exclusive microbiota (ASV-ENV), except that an ASV mapping to Conexibacter was a significant indicator of the DNR population in the salamander exclusive microbiota. Despite the lack of indicator taxa, there were significant differences in overall composition of skin microbiota across salamander populations. This was true regardless of the chosen metric or taxonomic scale considered (Jaccard PERMANOVA: p-value = 0.001, see Figure 5A, SI Figures 5, 6, 7 SI Table 5). Interestingly, not only were salamander microbiota more similar within versus between populations, but also, salamander microbiota were more similar to crevice microbiota from their own population versus from other populations (see SI Figure 8). Unlike composition, green salamander microbiota α-richness did not vary across populations (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 10.9, df = 8, p-value = 0.21; see Figure 5B, see also SI Figure 9, 10, 11). Differences in γ-richness, however, were significant, with populations 1250, 1251 and DNR exhibiting lower γ-diversity and populations TR2, BB and 1292 exhibiting higher γ-diversity (see Figure 5C).

(a) PCoA based on ASV Jaccard distances comparing composition across the nine local populations. (b) ASV richness per salamander (alpha diversity) compared across the nine local populations; (b) ASV accumulation curves (population gamma diversity) compared across the eight local populations with (n > 2 salamanders). In all panels we use the following color scheme: HW1 (pink), BB (yellow), DNR (brown), 1250 (red), 1251 (blue), 1292 (green), TR2 (grey), 3688 (orange), and 1477 (purple).

Does spatial or genetic proximity explain variation in salamander microbiota?

Most Mantel tests demonstrated significant correlations between host geographic distance and salamander skin microbiota dissimilarity (Jaccard dissimilarity: r = 0.24, p-value = 0.0001). This was particularly true for phylogenetically agnostic metrics (Jaccard, Bray-Curtis), whereas correlations were only marginally significant for phylogenetically aware metrics (UniFrac, weighted UniFrac, see SI Table 6). Mantel correlograms likewise indicated that salamander skin microbiota from populations separated by small geographic distances were more similar than average, and salamander skin microbiota separated by large geographic distance were less similar than average (Figure 6D, see also SI Figures 12–19). Notably, this pattern was observed for the full salamander skin microbiota, the component of the salamander skin microbiota exclusive to salamanders and the component of the salamander skin microbiota shared with their environment (i.e., shared with crevices). This same pattern was not, however, observed in crevice microbiota. Rather, there was no significant distance-decay relationship across crevices (Jaccard: r = −0.01, p-value = 0.51), and this held for the full crevice microbiota, the component of the crevice microbiota that was exclusive to crevices and the component of the crevice microbiota that was shared with salamanders (see SI Table 7). Further, in almost all cases, Mantel correlograms indicated that crevice microbiota from sites in close spatial proximity were not more similar than crevice microbiota from sites spatially distant from one another (see Figure 6F, SI Figures 12–19). In addition, Mantel tests found no evidence that median population dissimilarity of salamander microbiota was correlated with median population dissimilarity of crevice microbiota (Jaccard: r = 0.0051, p-value = 0.503, see SI Figure 8).

Plots of Jaccard similarity for salamander skin microbiota as a function of geographic distance (a), (n = 66), salamander skin microbiota as a function of genetic distance (b), (n = 46) and crevice microbiota as a function of geographic distance (c), (n = 20). Corresponding Mantel correlograms for salamander skin microbiota (d,e) and crevice microbiota (f) as a function of geographic distance (d,f) and genetic distance (e). Points on the correlogram filled in with solid color indicate a significant correlation between geographic/genetic distance and microbiota similarity at that distance class. Across all panels, microbiota components are colored as follows: full salamander skin microbiota (bright green), the salamander exclusive component of skin microbiota (yellow-green), the component of the salamander skin microbiota shared with crevice microbiota (olive green), the full crevice microbiota (grey-brown), the crevice exclusive component of the crevice microbiota (grey) and the component of the crevice microbiota shared with salamander skin (forest green).

In general, the salamander exclusive component of the skin microbiota was less similar across salamanders, both within and between populations, as compared to the component shared with the environment (see Figure 6A, SI Figures 12–19). For Jaccard similarity, the salamander exclusive component also decayed more rapidly with distance, although this was not true for all dissimilarity metrics. Interestingly, the crevice exclusive component of the crevice microbiota was also less similar than the component shared with salamanders (see Figure 6C, SI Figures 12–19). Slopes of the Jaccard distance-decay curve for salamander skin microbiota suggested a halving distance of approximately 30 kilometers see Figure 6A-C).

In addition to geographic distance, independent Mantel tests also demonstrated significant correlations between population-level genetic relatedness and skin microbiota dissimilarity (Jaccard: r = 0.33, p-value = 0.0001). Again, this trend was stronger for phylogenetically agnostic metrics and weaker for phylogenetically aware metrics, with no significant correlation based on weighted UniFrac (SI Table 8). Mantel correlograms also showed that more closely-related (genetic) populations had skin microbiota that were more similar than average, and less closely-related populations had skin microbiota that were less similar than average (see Figure 6E).

Do local population characteristics explain variation in salamander microbiota?

Neither median α-richness (see Figure 7A-E) nor median γ-richness (see Figure 7F-J) varied significantly with local population crevice count (α-richness: p = 0.441, γ-richness: p = 0.196), outcrop size (α-richness: p = 0.44, γ-richness: p = 0.893), population abundance (α-richness: p = 0.304, γ-richness: p = 0.071), salamander density per crevice (α-richness: p = 0.90, γ-richness: p = 0.686), or salamander density based on outcrop size (α-richness: p = 0.35, γ-richness: p = 0.118). Results were similar for most other metrics; although Shannon diversity decreased significantly with crevice count, which was opposite to our predictions. The only significant association between similarity and site characteristic was found with outcrop size (see Figure 7l, p= 0.02), all other similarity regressions were highly insignificant.

Linear regressions for richness against crevice count (a), outcrop size (b), population abundance (c), hosts/crevice (d) and hosts/m2 of outcrop (e) and for within-population Jaccard dissimilarity against crevice count (f), outcrop size (g), population abundance (h), hosts/crevice (i), and hosts/m2 of outcrop (j).

Do Chytrid-inhibitory ASV richness and relative abundance differ between local populations?

Green salamander microbiota Chytrid-inhibitory ASV α-richness varied significantly across populations (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 25.43, df = 8, p-value = 0.001 see Figure 8A). Mean Chytrid-inhibitory ASV α-richness in our lowest population was approximately half of what we observed in our highest population (means of ~20 vs. ~40 ASVs per salamander). However, the proportion of reads per salamander mapping to the Chytrid-inhibitory sequences did not vary significantly across populations (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 12.78, df = 8, p-value = 0.12; Figure 8B), even though the lowest population proportion was approximately half of the highest population proportion (~0.2 vs ~0.4; see Figure 8B). Further, although Chytrid-inhibitory ASV richness varied significantly across populations, post-hoc pairwise Wilcox tests with Benjamini & Hochberg corrections for multiple comparisons did not find any specific pairs of populations that were significantly different. That said, without corrections for multiple comparisons, we found many significant differences between pairs of populations (see SI Table 9).

Discussion

In this paper, we examined spatial patterns of skin microbiota diversity and composition across a system of green salamander populations. We also considered the relationship between salamander skin microbiota and the microbiota of the salamander environment. This allowed us to ask how dispersal, acting at both the host and the microbial scale, interacts with other community assembly processes, including microbial scale selection and microbial scale drift to impact the spatial structure of salamander skin microbiota.

Processes structuring salamander skin microbiota

First and foremost, we found strong differences in composition between salamander skin and crevice microbiota (Figures 3, 4). This provides evidence for microbial scale selection and is consistent with previous studies64,65 which found that amphibian skin could actively exclude certain environmental microbes. Within the context of dispersal, microbial scale selection is important because it enables host scale dispersal to impact spatial patterns in salamander skin microbiota. By contrast, if salamander skin microbiota were identical to their crevice environment, then skin microbiota would be more impacted by dispersal limitation of environmental microbes (microbial scale dispersal) than by dispersal limitation of the salamanders themselves (host scale dispersal).

In contrast to microbial scale selection, we found little evidence for host scale selection. Significant host scale selection should have emerged as differences in skin microbiota across host populations. While we did observe differences, these differences followed a classic pattern of distance-decay, suggesting that dispersal, rather than selection, was the most likely cause. Certainly, it is possible for selection to yield patterns of distance-decay. This typically occurs when environmental similarity decreases with increasing distance. However, selection should have resulted in distance-decay in both skin and crevice microbiota. Further, selection should have resulted in population level correlation between median skin microbiota similarity and median crevice microbiota similarity, which we did not observe. The fact that we did not see distance-decay in crevice microbiota and that there was no correlation between skin and crevice microbiota dissimilarity argues against a strong role for host scale selection. This is in keeping with our understanding of our study system. In particular, because our sampled salamander populations span a relatively small geographic range (~40 km), all within the Blue Ridge ecoregion, and because our populations all occur in the same type of habitat (granite rock outcrops within mixed deciduous forests), they all experience broadly similar environments. This should minimize the potential for host scale selection.

While the patterns of spatial variation that we observed were not strongly suggestive of host scale selection, they did indicate a role for host scale dispersal (Figure 6A, C, SI Figures 12–19). In particular, our results suggested that higher levels of salamander movement between populations homogenizes skin microbiota, while barriers (in our case distance) to host scale dispersal cause an increase in skin microbiota dissimilarity. Admittedly, other dispersal mechanisms beyond host translocation could result in similar patterns of distance-decay. Microbes could, for example, be transferred by a different but comparably dispersal limited host species. Alternatively, microbes could be transported by wind or water at rates dependent on distance. However, the lack of distance-decay in crevice microbiota, along with the unique crevice habitat that is both partially occluded and primarily occupied by green salamanders, makes these routes less likely (though other salamander species are occasionally found in the lower rock crevices alongside green salamanders at some of our populations). The observation that green salamander skin microbiota are structured by host scale dispersal is consistent with our understanding of green salamander biology. Past research indicates that green salamander dispersal capabilities are generally limited to very short geographic distances (≤50 m)66,67,68,69. Further, recent work investigating the genetic relatedness of green salamander populations has shown evidence of isolation by distance (see Caveats and Future Directions for additional discussion). This, again, indicates that green salamanders are dispersal limited in agreement with previous literature70. Thus, it is not overly surprising that host scale dispersal impacts spatial patterns in green salamander skin microbiota.

In contrast to host scale dispersal, our system provided weaker/mixed evidence for the importance of microbial scale dispersal. Supporting a role for microbial scale dispersal is the overall low similarity of skin microbiota, even within sites, as well as the difference in similarity between the salamander exclusive component of the skin microbiota as compared to the component shared with the environment. Although low overall similarity could be explained by either microbial scale dispersal limitation or microbial scale selection (e.g., environmental filtering due to variable host genetics), the lower similarity of the host exclusive component is harder to explain based on selection. Rather, it suggests that there are microbe-specific differences in community assembly processes between host-specific and environmental microbes. While it is possible that other features of these microbial subsets might vary in ways that impact community assembly, their modes of dispersal are an obvious candidate. In particular, host-specific microbes likely require host-to-host contact71. Thus, salamanders must be in the same place at the same time. Since green salamanders are not highly gregarious, rates of host-host contact could easily be limiting. By contrast, environment-to-host transfer merely requires that salamanders contact rock surfaces. Given that salamanders are relatively mobile within their rock outcrop, there should be a much lower dispersal barrier for microbes that can persist in the environment (i.e., away from the host). Refuting a role for microbial scale dispersal limitation, however, is the fact that neither skin microbiota similarity nor richness varied with host population density, despite differences in estimated salamander densities ranging from 0.08 to 0.24 salamanders per crevice and 0.01–0.03 salamanders per m2 of rock outcrop (see Figure 7). If microbial scale dispersal limitation was truly a dominant driver of skin microbiota assembly, then both microbiota similarity and microbiota richness should have increased with salamander density, at least based on the reasonable assumption that density impacts host-host contact rates.

Like microbial scale dispersal, the effects of microbial scale drift were also weaker in our system. Certainly, observing any form of dispersal limitation (see above) implies that either drift or speciation creates differences that dispersal can act upon. However, if microbial scale drift was highly significant, we would have expected that skin microbiota richness would increase with host population abundance, crevice count and outcrop surface area. This is because all of these population-level characteristics should have impacted the probability of microbial extinction. Arguably, the lack of relationship between skin microbiota richness and outcrop size could be explained by the fact that outcrop size is not an accurate measure of the spatial area used by either individual salamanders or the salamander population as a whole. It is less clear why salamander abundance did not impact skin microbiota richness.

Functional implications of spatial variation

In amphibians, such as the green salamander, the skin microbiota is particularly important because certain skin microbial taxa are known to protect hosts against chytridiomycosis16,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85. Further, the relative abundances and diversity of chytrid-inhibitory taxa negatively correlated with Bd infection intensity62. Thus, characterizing and identifying the underlying drivers of variation in skin microbiota, and understanding how this impacts Chytrid-inhibitory activity, has broad conservation implications. This includes identifying population characteristics that might result in microbiota with higher or lower levels of Chytrid-inhibitory activity, as well as identifying how the movement and spatial structuring of Chytrid-inhibitory microbial activity relates to salamander movement overall. The latter could aid in developing management strategies to better protect at-risk populations (e.g., introducing protective bacterial strains86 to more isolated local populations).

In our system we found substantial variation in the richness of Chytrid-inhibitory ASVs across local populations (Figure 8A). Indeed, our highest population had more than double the Chytrid-inhibitory isolate richness of our lowest population. This is somewhat surprising, since we did not find significant differences in ASV richness overall. Thus, the taxonomic richness of certain functional classes appears to vary more than taxonomic richness itself. This is opposite to findings in some systems, where function is preserved even when taxonomy is variable14. Differences in the richness of Chytrid-inhibitory isolates can impact population resilience to chytridiomycosis62 following Bd or Bsal introduction, for example by attacking Bd and/or Bsal using different mechanisms or by being active under different conditions. Unfortunately, while our populations varied in ASV richness, this variation was not predicted by any of the local population characteristics that we measured, suggesting that other, unstudied population traits are at play.

Caveats and future directions

One of the most important caveats in our system is that we cannot disentangle geographic distance from host genetic distance. In particular, the pattern of distance-decay that we observe may arise not only due to differences in host translocation from one population to another (see above), but also due to differing host genetics between populations (i.e., microbial scale selection). Unfortunately, in our system, hosts genetic distance and population distance are strongly correlated. Indeed, Mantel tests show equally significant relationships with skin microbiota similarity when population geographic distance was replaced with host genetic distance (see Figure 6B, E). This is not surprising – the same barriers to host dispersal that can cause spatial patterns in translocation of microbes can also cause spatial patterns in translocation of host genes87. Notably, despite significant isolation by distance, there is relatively minimal genetic divergence among populations. This suggests that translocation of microbes may be more important than host genetics in governing the spatial patterns that we observe. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that host genetics plays a significant or even dominant role. Future studies that can identify populations where genetic distance is not fully correlated with host dispersal barriers could help to provide insight into the relative roles of host translocation versus host genetics in structuring amphibian skin microbiota.

Another caveat of our study was that differences in population size and density, as well as outcrop size were relatively small across our entire study system. For example, our population abundances ranged from 8 to 24 salamanders per population spanning just one order of magnitude. The generally high variability of skin microbiota, combined with relatively narrow ranges for population characteristics, could have made it difficult to detect trends that might have otherwise supported a stronger role for microbial scale dispersal and/or microbial scale drift. On the other hand, these processes may be less important than predicted based on classic theories like Island Biogeography and the patch-dynamic metacommunity framework when it comes to governing HA microbiota. With this in mind, it is interesting to note that relatively constant α-diversity was recently noted across a metapopulation of bighorn sheep gut microbiota as well37. Future studies should examine trends in HA microbiota across wider ranges of population sizes to determine whether there is a relationship or whether HA microbiota are, in fact, largely robust to host population characteristics. Unfortunately, this may not be possible in the BRE, given the low density and small population sizes of green salamanders in this region70. However, it may be possible for other green salamander clades.

Conclusions

Our study is useful for understanding how multiscale dispersal and dispersal limitation impacts HA microbiota, and also provides insight in an applied conservation perspective. Broadly speaking, we found trends consistent with metapopulation theory, suggesting that host movement between local populations (host scale dispersal) and host-host contact (microbial scale dispersal) are important drivers of HA microbiota assembly. An interesting next step would be to extend our study to a larger range of spatial scales, allowing us to explore not only selection, drift and dispersal, but also host and microbial scale speciation. This could, for example, be done by comparing skin microbiota across all clades within the green salamander complex.

Hosts and their HA microbiota are inextricably linked, such that the ecology of the host impacts the ecology of it’s HA microbiota and vice versa. In this study, we considered spatial ecology and, in particular, how host and microbial scale dispersal and dispersal limitation influence the spatial ecology of HA microbiota. More broadly, understanding how the ecological processes of hosts (host scale) and their HA microbiota (microbial scale) impact one another, the feedback processes that dictate their mutual outcomes, and how these outcomes have emerged over years of coevolution and codiversification is an important step towards developing a unifying theory of multiscale ecology.

Methods

Study system and metapopulation characterization

The green salamander, Aneides aeneus, is a member of the family Plethodontidae and is one of only two Aneides species in the eastern United States. Relative to other salamanders, green salamanders are unique because they primarily inhabit small crevices with stable microclimates within discrete rock outcrops88,89. This lifestyle confers high population patchiness (green salamander populations rarely spillover onto adjacent forest floors)88, making green salamanders an ideal organism for studying the effect of a patchy host metapopulation structure on HA microbiota spatial distribution. Further, the uniqueness of the rock outcrop habitat limits interspecific interactions, allowing us to focus on the population of a single host that is not confounded by frequent contact with other salamander species (although, we do occasionally find other plethodontids in the lower crevices at some of our sites). Overall, this creates a system where we can assume that microbial colonization and recolonization of green salamander HA microbiota is almost exclusively from conspecifics and localized crevice environments. This simplifies our system and allows us to better identify the reservoirs from which HA microbes are recruited and the factors governing their assembly into salamander microbiota.

Skin microbiota sampling

We sampled the skin microbiota from 74 green salamanders in the Blue Ridge Escarpment (BRE) Clade89. Salamanders were sampled across nine local populations (Figure 1), which together comprise a metapopulation70. All salamanders were sampled between September and November. However, due to the overall low density of green salamanders in the BRE, and the resulting difficulty of finding sufficient numbers of unique individuals from each population, sampling took place over a three-year period from 2021 to 2023. Salamanders were sampled over a three-year period because of the difficulty of finding salamanders in the BRE and, as a consequence, the time required to catch sufficient numbers across all of our populations. Because we recognized this challenge, we attempted to distribute sampling efforts across as many sites as possible in each year, although there were some years where we were unable to catch salamanders from certain locations, and several additional populations were added in the second year, due to our inability to find salamanders at initially targeted locations. Collections were done under SC permit N-10-18. All experimental protocols were approved by Clemson IACUC under AUPs 2021-07 and 2021-025, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and all methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Prior to sampling, all salamanders were washed in sterile MilliQ water that had been autoclaved at 121 °C for an hour. This was done following the protocol from Walker et al. 201590. Briefly, salamanders were first held in a gloved hand and rinsed with a squirt bottle to remove large debris. Salamanders were then transferred to a sterile petri dish, where they were rinsed twice more by filling the petri dish with sterile MilliQ water and gently swirling the salamander for approximately 30 s. Salamander skin microbiota were then sampled90 by gently rubbing a sterile rayon tipped swab (MWE 113; Medical Wire Equipment) along the entire length of the right, left, dorsal and ventral sides of each animal approximately 15 times following the protocol from Walker et al. 202091. A second swab was then collected using the same method to test hosts for Bd or Bsal. Swabs were placed on dry ice until they could be transferred to a − 20 °C freezer for storage that same day. We also collected morphometric data on each individual, including snout-vent-length (SVL), tail length, and total length. As well, we recorded whether the captured individual displayed any visible signs of chytridiomycosis, was missing their tail, or was found with another green salamander in the same crevice at time of capture. Finally, we photographed the dorsum of each individual and used I3S Pattern software (https://reijns.com/i3s/i3s-pattern/) to determine whether each swab came from a new or previously sampled salamander. Environmental control samples were similarly collected by swabbing a subset of the crevices that green salamander individuals were found in at time of capture. Though no salamanders were euthanized, we did include a euthanasia statement in our IACUC AUP detailing if a salamander is accidentally injured in the wild to a point beyond recovery, the individual will be euthanized via a manual application of blunt force trauma to the head. Secondary method is decapitation with a sharp knife or scissors.

Population level characteristics

A recent demographic analysis of numerous green salamander populations within the Blue Ridge Escarpment (BRE) clade in South Carolina documented genetic isolation by distance between several populations, suggesting that salamanders in the BRE are dispersal limited. Furthermore, this analysis identified a plethora of population characteristics (e.g., population abundances, outcrop sizes, crevice counts) for each subpopulation, allowing us to test basic premises of microbial scale drift and dispersal70. We used capture-mark-recapture (CMR) population abundance estimates, rock outcrop size measurements, crevice counts, and population genetic structure (FST) based on restriction-site associated DNA sequencing (RADSeq) from Novak70 to characterize the size and genetic isolation of each population within our metapopulation. For size, we considered both absolute measurements and densities (i.e., dividing CMR-estimated abundance by outcrop size or crevice counts). RADSeq data, outcrop size, and crevice counts were available for all our local populations. CMR-estimated abundances (and by extension, densities) were only available for seven out of nine local populations (populations “BB” and “1251” were not available). Metapopulation and population characteristics as well as sample sizes for each of our populations are presented in Supplementary Information (SI) Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Sequencing and taxonomic assignment

Microbiota swabs were sent to the Minnesota Genomics and Bioinformatics Center for sequencing. DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Extraction Kit. Extracted DNA was amplified for 30 cycles using the Quick-16S Primer Set (515F-806R primers) which target the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. PCR products were then sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq using a v3 reagent kit for 600 cycles. FASTQ files returned from the Minnesota Genomics and Bioinformatics Center were analyzed in-house using a prepared Qiime292 pipeline (included in SI). Briefly, reads were filtered and processed using dada293 with default trim and length settings changed to: --p-trim-left-f 19, --p-trim-left-r 20, --p-trunc-len-f 225, --p-trunc-len-r 225. A phylogenetic tree was then created using the Qiime2 align-to-tree-mafft-fasttree function. Next, we trained a naïve bayes classifier specific to our primer sets using the feature-classifier Qiime2 function. We then grouped sequenced reads into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Finally, ASVs were taxonomically classified using the Silva 99% similarity database and outputted as BIOM files for subsequent analysis. All code and data are included in the github repository listed in the data availability statement.

Bd swabs were extracted in-house using the ZymoBIOMICS DNA Microprep kit (catalogue number D3401) following the manufacturer’s protocol with the following modifications to increase DNA yield: we added 600 µL input of swab lysate instead of the standard 400 µL. In addition, we added no additional lysis buffer and incorporated 1800 µL of binding buffer to the lysate. We skipped steps 4, 12, and 13 (contaminant/inhibitor filtering steps) due to the low input nature of our samples and heated the elution buffer to 60 °C. Samples were lysed for 40 min using a TissueLyser 2 and 20 min in a vortex genie at maximum speed. Bd assays were performed on extracted skin swabs in triplicate via qPCR following the protocol from Boyle et al 200494 and using 15 µL reactions with 12 µL of master mix and 3 µL of extracted skin swab DNA. Samples were considered positive if 2/3 replicates positively amplified.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analysis was performed in R (version 4.2.1)95 using the phyloseq package96 (v. 1.41.1) for manipulation of BIOM files. We did not include microbiota samples from hosts which tested positive for Bd, had previously been sampled, or displayed skin lesions consistent with chytridiomycosis (even if they did not test positive for Bd). We removed any ASVs found in any of our three sequencing blanks as potential contamination. We also did not include microbiota samples with a final read depth less than 5000 (see SI Figure 20 for rarefaction curves), considering these sequencing failures. This left a total of 66 unique salamander samples and 20 unique crevice samples in our dataset. From these samples, we removed all sequences which could not be classified to phylum. We also removed all eukaryotic sequences and sequences classified as either mitochondria or chloroplasts, leaving only bacterial and archaeal ASVs. We then rarified our samples, without replacement, to 5000 sequences per sample. All analyses were done at three levels: ASVs, taxa collapsed to genus-level using the tax_glom function from the phyloseq package, and ASVs with environmental microbes removed (henceforth “ASV-ENV”).

Differential occupancy analyses: predicted occupancy in salamander microbiota was estimated based on relative abundance and occupancy of each microbial taxa in crevice microbiota by using the neutral model developed by Sloan et al97. Briefly, we used crevice microbiota samples to predict m (the probability that a vacancy in the local population is filled by an immigrant) and then used this value of m, in combination with the mean number of reads per sample and total number of samples from salamanders, in order to predict salamander occupancy. This was done using a modified version of the sncm.fit_function.r, written by Burns et al. We did not account for year effects in this analysis.

α-diversity analyses: we assessed α-diversity using richness (phylogenetically agnostic incidence), Faith’s PD (phylogenetically aware incidence), and Shannon Diversity (phylogenetically agnostic abundance). Faith’s PD was calculated using the pd function from the picante package (v. 1.8.2)98, while Shannon Diversity was calculated using the diversity function from the vegan package (v. 2.6.4)99. Richness was calculated by summing columns in the presence/absence ASV table. We compared α-diversity between crevices and green salamander skin microbiota with a Mann-Whitney U test using the wilcox.test function from the stats package (v. 4.2.1). We compared α-diversity across all nine local populations with a Kruskal-Wallis test using the kruskal.test function from the stats package (v. 4.2.1). When the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated significant differences between at least two local populations, we performed pairwise post-hoc testing by applying pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests with a Benjamini-Hochberg correction using the pairwise.wilcox function from the stats package (v. 4.2.1). In addition, we regressing α-diversity against site or type (crevice vs. salamander) and year (as a factor) using the glm function from the stats package. We then applied a stepwise AIC using the stepAIC function from the MASS package to remove insignificant variables.

γ-diversity analyses: we assessed \(\gamma\)-diversity using skin microbiota from salamanders versus crevices and using salamanders from each site. More specifically, we calculated species accumulation curves (SACs) for ASV richness using the iNEXT3D function from the iNEXT.3D package using the ‘raw_incidence’ datatype. We then tested for significant differences based on overlap of 95% intervals, also calculated with the iNEXT3D function. We did not account for year effects in our \(\gamma\)-diversity analysis, nor did we consider phylogenetic metrics or abundance.

Compositional analyses: To assess differences in composition among local communities, we used Jaccard (phylogenetically agnostic incidence), Bray-Curtis (phylogenetically agnostic abundance), Unifrac (phylogenetically aware incidence), and weighted UniFrac (phylogenetically aware abundance) metrics. We compared microbiota composition between crevices and green salamander skin and between local populations using the adonis2 function from the vegan package (v.0.2.0)99. When PERMANOVA indicated significant differences between at least two local populations, we additionally performed post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Benjamin-Hochberg corrections using the pairwiseAdonis package (v. 0.4.1)100 to determine which populations were distinct from one another. We did not account for year effects in post-hoc tests. Following our PERMANOVA tests, we assessed differences in dispersion between groups (i.e., salamanders vs. crevices and local populations) using the betadisper function from the vegan package (v. 2.6.4)99. The significance of differences in dispersion between groups was then determined with ANOVA using the anova function from the stats package (v. 4.2.1). Finally, we visualized differences in overall microbiota composition among sites using principal coordinates analyses (PCoA).

In addition to overall differences in composition, we also tested for differences in the abundance and/or occurrence of specific microbial taxa between groups (i.e., salamanders vs. crevices and local populations). This was done with two methods: (1) using analysis of communities with bias correction (ANCOM-BC2, a form of differential abundance analysis commonly employed in microbiota literature)101, and (2) based on the Indicator Value Index (IndVal, an indicator species method that assesses the combination of differences in relative abundance and differences in occurrence across groups). ANCOM-BC2 was performed using the ancombc2 function from the ANCOMBC package (v. 1.6.4) while IndVal was performed using the multipatt function from the indicspecies package (v. 1.7.14)102. As in the original IndVal method, for analysis of local populations, we only considered differences between a single local population and the remaining populations, rather than differences between combinations of local populations. For ANCOM-BC2, we considered all ASVs and all genera for ASV- and genus-level analysis respectively. However, to reduce the false discovery rate, for IndVal we considered all genera but only considered ASVs found at relative abundances >1% across the whole dataset. We did not account for year effects in either ANCOM-BC2 or indicator species analysis.

Distance decay: we assessed patterns of distance-decay among green salamander skin microbiota using Mantel tests. Mantel correlations were calculated using Jaccard, Bray-Curtis, Unifrac, and weighted Unifrac indices. We used the mantel function in the vegan package (v. 2.6.4)99 to assess overall geographic distance-decay between our 66 green salamander microbiota across nine sites. The same was done between our 20 crevice microbiota. We then used the mantel.correlog function, also in the vegan99 package, to calculate mantel correlations at varying geographic distance classes. Geographic distance correlograms were calculated using seven distance classes (0 (within-population), 100, 1000, 5000, 10000, 20000, and 45000 meters). At six of our nine sites, we also had Fst values, allowing us to assess patterns of skin microbiota distance-decay as a function of (average) genetic relatedness between populations. For this analysis, we did not have genetic data from the specific salamanders that we sampled. Rather, we used genetic data from a previous study of the same populations70. Consequently, we could not use individual salamander Fst values. Instead, all salamanders (n = 46) from the same site were assigned the same population-level Fst estimated in Novak et al.70 Prior to analysis of distance-decay, all slightly negative Fst (−0.036 and −0.038) values were changed to 0. Genetic distance correlograms were calculated using five distance classes (0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2) spanning the distribution of the observed population-level genetic differentiation. All Mantel tests were done using 9999 permutations and correlations deemed significant at an alpha level of 0.05. We did not account for year effects in Mantel tests.

To calculate the rate of decay of microbiota similarity with distance, we converted distance matrices to similarity matrices by subtracting the distance matrix from 1 (i.e., “1-matrix value”). We then linearly regressed the log-transformed skin microbiota similarity values for each pairwise salamander comparison against the distance between the pair of salamanders. This allowed us to estimate a slope associated with similarity decay. This was done across all similarity metrics (Jaccard, Bray-Curtis, Unifrac, and weighted Unifrac) and at all taxonomic levels. We then calculated how quickly between-population similarity reached 50% of within-population similarity (the ‘halving distance’)103 using formula 1 in the SI which was repeated for all metrics at the ASV level.

Local population characteristics: we regressed median α-diversity, \(\gamma\)-diversity and similarity against estimates of host patch size (outcrop size and crevice count), host abundance, and host density (animals/m2 and animals/crevice). Because salamander population abundance estimates using CMR and Polluck’s Robust design104 were only available for seven of our nine sites, regressions involving host abundance and host density were restricted to seven sites for α- and \(\gamma\)-diversity and similarity. Regressions involving patch size considered all nine sites for α-diversity, but only eight of our nine sites for \(\gamma\)-diversity and similarity, with the latter being restricted by the limited number of animals at HW1. α-diversity was calculated as described above. Median α-diversity was taken over all animals at each local population. Similarity was likewise calculated as mean Jaccard, Bray–Curtis, UniFrac or weighted UniFrac distance within each population. \(\gamma\)-diversity was calculated based on the estimated value at N = 10 salamanders for each population as predicted by the iNEXT.3D function.

Chytrid-inhibitory analyses: we exported our rarified microbiota dataset as a BIOM file, imported it into Qiime2, and filtered out representative sequences and features which were no longer present following rarefication. We used the Qiime2 function qiime vsearch cluster-features-closed-reference to match our sequences with clustered Anti-Bd and Anti-Bsal ASVs from the AmphiBac_InhibitoryStrict_2023.2 database16, generously provided by Dr. Molly Bletz. Sequences exhibiting 99% similarity were classified as possessing Chytrid-inhibitory properties. We calculated Chytrid-inhibitory ASV richness as well as the total proportion of reads mapping to the Chytrid-inhibitory database (Chytrid-inhibitory ASVs divided by the rarefication value) per salamander to determine the relative proportion of bacteria with Chytrid-inhibitory properties in the entire skin microbiota. Finally we compared Chytrid-inhibitory ASV richness and proportions between populations with a Kruskal-Wallis test using the kruskal.test function from the stats package (v. 4.2.1). When the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated significant differences between at least two clades, we performed pairwise post-hoc testing by applying pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests with a Benjamini-Hochberg correction using the pairwise.wilcox function from the stats package (v. 4.2.1).

Data availability

All supplemental materials including data and code are housed in the github repository https://github.com/dmalago/Green_Salamander_Metapopulation_Microbiome. The readme file within describes all materials. Raw sequence files are also located in the NCBI SRA under project number PRJNA1176676, ID: 1176676.

References

McCoy, K. D., Ronchi, F. & Geuking, M. B. Host-microbiota interactions and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 279, 63–69 (2017).

Collado, M. C., Cernada, M., Baüerl, C., Vento, M. & Pérez-Martínez, G. Microbial ecology and host-microbiota interactions during early life stages. Gut Microbes 3, 352–365 (2012).

Ezenwa, V. O., Gerardo, N. M., Inouye, D. W., Medina, M. & Xavier, J. B. Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science 338, 198–199. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227412 (2012).

Lewis, Z. & Lizé, A. Insect behaviour and the microbiome. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 9, 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2015.03.003 (2015).

Dunbar, H. E., Wilson, A. C. C., Ferguson, N. R. & Moran, N. A. Aphid thermal tolerance is governed by a point mutation in bacterial symbionts. PLoS Biol 5, 1006–1015 (2007).

Moeller, A. H. et al. The lizard gut microbiome changes with temperature and is associated with heat tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01181-20 (2020).

De La Torre Canny, S. G. & Rawls, J. F. Baby, it’s cold outside: Host-microbiota relationships drive temperature adaptations. Cell Host Microbe 18, 635–636 (2015).

Everard, A. et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 9066–9071 (2013).

Chevalier, C. et al. Gut microbiota orchestrates energy homeostasis during cold. Cell 163, 1360–1374 (2015).

Brune, A. Symbiotic digestion of lignocellulose in termite guts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3182 (2014).

Brune A, Ohkuma M (2011) Role of the termite gut microbiota in symbiotic digestion. In Biology of Termites: A Modern Synthesis. Springer Netherlands, USA, 439–475

Vaelli, P. M. et al. The skin microbiome facilitates adaptive tetrodotoxin production in poisonous newts. Elife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.53898 (2020).

Lenoir, A. & Devers, S. Alkaloid secretion inhibited by antibiotics in Aphaenogaster ants. C. R. Biol. 341, 358–361 (2018).

Bletz, M. C. et al. Amphibian skin microbiota exhibits temporal variation in community structure but stability of predicted Bd-inhibitory function. ISME J. 11, 1521–1534 (2017).

Bletz, M. Probiotic bioaugmentation of an anti-Bd bacteria, Janthinobacterium lividum, on the amphibian, Notophthalmus viridescens: transmission efficacy and persistence of the probiotic on the host and non-target effects of probiotic addition on ecosystem components. Masters Theses (2013).

Woodhams, D. C. et al. Antifungal isolates database of amphibian skin-associated bacteria and function against emerging fungal pathogens. Ecology 96, 595–595 (2015).

Trevelline, B. K., Fontaine, S. S., Hartup, B. K. & Kohl, K. D. Conservation biology needs a microbial renaissance: A call for the consideration of host-associated microbiota in wildlife management practices. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2448 (2019).

West, A. G. et al. The microbiome in threatened species conservation. Biol. Conserv. 229, 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.016 (2019).

Redford, K. H., Segre, J. A., Salafsky, N., Del Rio, C. M. & Mcaloose, D. Conservation and the microbiome. Conserv. Biol. 26, 195–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01829.x (2012).

Zhu, L., Wang, J. & Bahrndorff, S. Editorial: The wildlife gut microbiome and its implication for conservation biology. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.697499 (2021).

Bahrndorff, S., Alemu, T., Alemneh, T. & Lund Nielsen, J. The microbiome of animals: Implications for conservation biology. Int. J. Genom. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5304028 (2016).

Jiménez, R. R. & Sommer, S. The amphibian microbiome: natural range of variation, pathogenic dysbiosis, and role in conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 26, 763–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1272-x (2017).

Banerjee, A., Cornejo, J. & Bandopadhyay, R. Emergent climate change impact throughout the world: call for “Microbiome Conservation” before it’s too late. Biodivers. Conserv. 29, 345–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01886-6 (2020).

Jin Song, S. et al. Engineering the microbiome for animal health and conservation. Exp. Biol. Med. 244, 494–504 (2019).

Cheng, Y. et al. The Tasmanian devil microbiome-implications for conservation and management. Microbiome 3, 76 (2015).

Grice, E. A. & Segre, J. A. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2537 (2011).

Milani, C. et al. Multi-omics approaches to decipher the impact of diet and host physiology on the mammalian gut microbiome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01864-20 (2020).

Smith, R. P. et al. Gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep physiology in humans. PLoS ONE 14, e0222394 (2019).

David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014).

Kostic, A. D., Xavier, R. J. & Gevers, D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: Current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology 146, 1489–1499 (2014).

Toh, T. S. et al. Gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease: New insights from meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 94, 1–9 (2022).

Lees, H. et al. Age and microenvironment outweigh genetic influence on the Zucker rat microbiome. PLoS ONE 9, e100916 (2014).

Kubinyi, E., Bel Rhali, S., Sándor, S., Szabó, A. & Felföldi, T. Gut microbiome composition is associated with age and memory performance in pet dogs. Animals 10, 1488 (2020).

Morrison, P. K. et al. The equine gastrointestinal microbiome: Impacts of age and obesity. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03017 (2018).

Bana, B. & Cabreiro, F. The microbiome and aging. Annu. Rev. Genet. 53, 239–261 (2019).

Uren Webster, T. M., Consuegra, S., Hitchings, M. & Garcia de Leaniz, C. Interpopulation variation in the atlantic salmon microbiome reflects environmental and genetic diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e00691 (2018).

Couch, C. E. et al. Bighorn sheep gut microbiomes associate with genetic and spatial structure across a metapopulation. Sci. Rep. 10, 6582 (2020).

Kolasa, M. et al. How hosts taxonomy, trophy, and endosymbionts shape microbiome diversity in beetles. Microb. Ecol. 78, 995–1013 (2019).

Godon, J.-J., Arulazhagan, P., Steyer, J.-P. & Hamelin, J. Vertebrate bacterial gut diversity: size also matters. BMC Ecol. 16, 12 (2016).

Bletz, M. C. et al. Amphibian gut microbiota shifts differentially in community structure but converges on habitat-specific predicted functions. Nat. Commun. 7, 13699 (2016).

McKenzie, V. J. et al. The effects of captivity on the mammalian gut microbiome. Integr. Comp. Biol. 57, 690–704 (2017).

San Juan, P. A., Castro, I. & Dhami, M. K. Captivity reduces diversity and shifts composition of the Brown Kiwi microbiome. Anim. Microbiome 3, 48 (2021).

Bates, K. A. et al. Captivity and infection by the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans perturb the amphibian skin microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1834 (2019).

Barnes, E. M. et al. Assembly of the amphibian microbiome is influenced by the effects of land-use change on environmental reservoirs. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 4595–4611 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Experimental temperatures shape host microbiome diversity and composition. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 41–56 (2023).

Vellend, M. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. Q. Rev. Biol. 85, 183–206 (2010).

Koskella, B. & Bergelson, J. The study of host–microbiome (co)evolution across levels of selection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190604 (2020).

Limborg, M. T. & Heeb, P. Special issue: Coevolution of hosts and their microbiome. Genes 9, 549 (2018).

Groussin, M., Mazel, F. & Alm, E. J. Co-evolution and co-speciation of host-gut bacteria systems. Cell Host Microbe 28, 12–22 (2020).

Frazier, A. N. et al. Stochasticity highlights the development of both the gastrointestinal and upper-respiratory-tract microbiomes of neonatal dairy calves in early life. Animals 15, 361 (2025).

Furman, O. et al. Stochasticity constrained by deterministic effects of diet and age drive rumen microbiome assembly dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 1904 (2020).

Oliphant, K., Parreira, V. R., Cochrane, K. & Allen-Vercoe, E. Drivers of human gut microbial community assembly: coadaptation, determinism and stochasticity. ISME J. 13, 3080–3092 (2019).

Couch, C. E. & Epps, C. W. Host, microbiome, and complex space: Applying population and landscape genetic approaches to gut microbiome research in wild populations. J. Hered. 113, 221–234 (2022).

Miller, E. T., Svanbäck, R. & Bohannan, B. J. M. Microbiomes as metacommunities: Understanding host-associated microbes through metacommunity ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.09.002 (2018).

Gill, D. E. The metapopulation ecology of the red-spotted Newt, Notophthalmus viridescens (Rafinesque). Ecol. Monogr. 48, 145–166 (1978).

Gill, D. E. Density dependence and homing behavior in adult red-spotted Newts Notophthalmus viridescens (Rafinesque). Ecology 60, 800–813 (1979).

Alex Smith, M. & Green, D. M. Dispersal and the metapopulation paradigm in amphibian ecology and conservation: are all amphibian populations metapopulations?. Ecography 28, 110–128 (2005).

Duellman, W. E. & Trueb, L. Biology of Amphibians 959 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).

Sinsch, U. Migration and orientation in anuran amphibians. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2, 65–79 (1990).

Blaustein, A. R., Wake, D. B. & Sousa, W. P. Amphibian declines: Judging stability, persistence, and susceptibility of populations to local and global extinctions. Conserv. Biol. 8, 60–71 (1994).

Smith, M. A. & Green, D. M. Dispersal and the metapopulation paradigm in amphibian ecology and conservation: are all amphibian populations metapopulations?. Ecography 28, 110–128 (2005).

Nava-González, B. et al. Inhibition of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infection by skin bacterial communities in wild amphibian populations. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 666–676 (2021).

MacArthur, R. H. & Wilson, E. O. The Theory of Island Biogeography (Princeton University Press, 2001).

Fitzpatrick, B. M. & Allison, A. L. Similarity and differentiation between bacteria associated with skin of salamanders (Plethodon jordani) and free-living assemblages. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 88, 482–494 (2014).

Walke, J. B. et al. Amphibian skin may select for rare environmental microbes. ISME J. 8, 2207–2217 (2014).

John RR. Movement, Occupancy, and Detectability of Green Salamanders (Aneides Aeneus) In Northern Alabama. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, United States – Alabama. (2017).

Waldron, J. L. & Humphries, W. J. Arboreal habitat use by the green salamander, Aneides aeneus, in South Carolina. J. Herpetol. 39, 486–492 (2005).

Gordon, R. E. The movement of displaced green salamanders. Ecology 42, 200–202 (1961).

Gordon, R. E. A contribution to the life history and ecology of the plethodontid salamander Aneides aeneus (Cope and Packard). Am. Midl. Nat. 47, 666–701 (1952).

Novak, M. An Integrative Approach to Managing a Species of Conservation Concern: Resource Selection, Spatial Ecology, and Population Genetics of the Green Salamander (Aneides aeneus) (Clemson University, 2024).

Ritchie, K. L., Vredenburg, V. T., Chaukulkar, S., Butler, H. M. & Zink, A. G. Social group size influences pathogen transmission in salamanders. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 75, 136 (2021).

Jiménez, R. R. & Sommer, S. The amphibian microbiome: Natural range of variation, pathogenic dysbiosis, and role in conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 26, 763–786 (2017).

Jiménez, R. R. et al. Inhibitory bacterial diversity and mucosome function differentiate susceptibility of appalachian salamanders to chytrid fungal infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01818-21 (2022).

Piovia-Scott, J. et al. Greater species richness of bacterial skin symbionts better suppresses the amphibian fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Microb. Ecol. 74, 217–226 (2017).

Yap, T. A., Nguyen, N. T., Serr, M., Shepack, A. & Vredenburg, V. T. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans and the risk of a second amphibian pandemic. EcoHealth 14, 851–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-017-1278-1 (2017).

Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A. et al. Expanding distribution of lethal amphibian fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22, 1286–1288 (2016).

Sabino-Pinto, J. et al. First detection of the emerging fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Germany. Amphib. Reptil. 36, 411–416 (2015).

Gray, M. J. et al. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans: The North American response and a call for action. PLoS Pathog. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005251 (2015).

Richgels, K. L. D., Russell, R. E., Adams, M. J., White, C. L. & Grant, E. H. C. Spatial variation in risk and consequence of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans introduction in the USA. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3, 150616 (2016).

Blackburn, M. et al. First report of ranavirus and Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in green salamanders (Aneides aeneus) from Virginia, USA. Herpetol. Rev. 46, 357–361 (2015).

Gray, M. J. et al. Broad host susceptibility of North American amphibian species to Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans suggests high invasion potential and biodiversity risk. Nat. Commun. 14, 3270 (2023).

Nnadi, N. E. & Carter, D. A. Climate change and the emergence of fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009503 (2021).

Scheele, B. C. et al. Amphibian fungal panzootic causes catastrophic and ongoing loss of biodiversity. Science 1979(363), 1459–1463 (2019).

Yuan, Z. et al. Widespread occurrence of an emerging fungal pathogen in heavily traded Chinese urodelan species. Conserv. Lett. 11, e12436 (2018).

Berger, L. et al. History and recent progress on chytridiomycosis in amphibians. Fungal Ecol. 19, 89–99 (2016).

Muletz, C. R., Myers, J. M., Domangue, R. J., Herrick, J. B. & Harris, R. N. Soil bioaugmentation with amphibian cutaneous bacteria protects amphibian hosts from infection by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Biol. Conserv. 152, 119–126 (2012).

Hansen, M. M. & Mensberg, K.-L.D. Genetic differentiation and relationship between genetic and geographical distance in Danish sea trout (Salmo trutta L.) populations. Heredity 81, 493–504 (1998).

Snyder, D. H. The green salamander (Aneides Aeneus) in Tennessee and Kentucky. J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 66.4, 165-169 (1991).

Patton, A. et al. A new green salamander in the southern Appalachians: Evolutionary history of Aneides aeneus and implications for management and conservation with the description of a cryptic microendemic species. Copeia 107, 748–763 (2019).

Walker, D. M. et al. A Novel Protocol for Washing Environmental Microbes from Amphibian Skin. Herpetol. Rev. 46.3, 349-353 (2015).

Walker, D. M. et al. Variation in the slimy salamander (Plethodon spp.) skin and gut-microbial assemblages is explained by geographic distance and host affinity. Microb. Ecol. 79, 985–997 (2020).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0190-3 (2019).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 7, 688 (2016).

Boyle, D. G., Boyle, D. B., Olsen, V., Morgan, J. A. T. & Hyatt, A. D. Rapid quantitative detection of chytridiomycosis (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) in amphibian samples using real-time Taqman PCR assay. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 60, 141–148 (2004).

R Core Team. R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (2014).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Sloan, W. T. et al. Quantifying the roles of immigration and chance in shaping prokaryote community structure. Environ. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00956.x (2006).

Kembel, S. W. et al. Picante}: {R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26, 1463–1464 (2010).

Oksanen J et al. {vegan}: Community Ecology Package. https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan. (2022).

Martinez Arbizu P. {pairwiseAdonis}: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison using Adonis. (2017).

Lin, H. & Das, P. S. Multigroup analysis of compositions of microbiomes with covariate adjustments and repeated measures. Nat. Methods 21, 83–91 (2024).

Cáceres, M. D. & Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90, 3566–3574 (2009).

Soininen, J., McDonald, R. & Hillebrand, H. The distance decay of similarity in ecological communities. Ecography 30, 3–12 (2007).

Pollock, K. H. A capture-recapture design robust to unequal probability of capture. J. Wildl. Manag. 46, 752 (1982).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Supun Wellappuliarachchi, Zack Laughlin and Mason Thurman for their help collecting data. We would also like to thank Drs. Carly Muletz-Wolz, Molly Bletz, and Doug Woodhams for providing us with the most recent version of the Amphib-Bac database and their guidance in using it. Finally, we thank our anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback which has strengthened the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DAM and SB designed the experiment. DAM, SB, MN, AK, and BC collected the data. BH and BS led, collected data, and analyzed all analyses related to Bd. DAM and SB conducted the statistical analysis with input from KB, BH, BS, BC. All authors contributed to manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malagon, D., Novak, M., Barrett, K. et al. Spatial variation of skin-associated microbiota in a green salamander metapopulation. Sci Rep 15, 24738 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05305-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05305-5