Abstract

Drought is a widespread natural disaster, and rapid assessment of groundwater drought has become a challenge due to the lack of direct spatiotemporal observation of groundwater. We employed machine learning models and the Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP), a game theory-based interpretability method, to understand and predict the evolution of groundwater drought by evaluating eight models with SHAP analysis in the West Liao River Plain (WLRP), with a semi-arid climate. The research showed: (1) The XGBoost model, optimized by the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), achieved the highest performance (AUC: 0.922, F1-score: 0.84). (2) SHAP analysis revealed that the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) at 12- and 24-month scales (SPEI12 and SPEI24) were key predictors, with long-term meteorological drought causing delayed groundwater drought, exacerbated by over-extraction and urbanization. The local SHAP values confirmed the robust importance of long-term meteorological drought and precipitation, and identified the interaction between precipitation and meteorological factors responsible for groundwater drought. (3) Future projections under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario indicated a significant increase in drought-affected areas, with earlier onset, broader extent, and greater severity. This work provides a machine learning framework for evaluating groundwater drought characteristics driven by multiple factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the most severe natural disasters, drought has adverse effects on both the natural environment1 and socio-economic activities2,3. The impacts of drought typically evolve from meteorological drought to hydrological drought4 and eventually to agricultural drought5 during which groundwater storage may be affected6. When drought influences groundwater systems, it can cause a decrease groundwater recharge, as well as decreased groundwater storage and discharge7. This process gives rise to a unique type of drought known as groundwater drought, which can significantly undermine industrial and agricultural production, as well as ecosystems that rely on groundwater8. Groundwater drought is a continuous, slow, and complex process that often goes unnoticed until it has already persisted for a long time and caused significant losses. With climate change, it is expected that more severe and prolonged droughts will occur9,10. In recent years, climate change has profoundly influenced the hydrological cycle, precipitation patterns11 hydrologic fluxes12 and increased the frequency and severity of natural disasters13. These changes have significant impacts on agriculture14 and economic activities15 exacerbating the challenges posed by groundwater drought. Detecting, identifying, and predicting groundwater droughts is crucial, particularly in regions where groundwater serves as a critical water source, as its persistence may pose a serious threat to water security2,16,17.

Groundwater drought monitoring primarily relies on drought indices, with two widely used examples being the Standardized Groundwater Index (SGI) and the GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) Groundwater Drought Index (GGDI). Although these indices have improved drought quantification, several challenges remain. The lack of sufficient observation stations, uneven spatial distribution, and discontinuous recording severely limit direct monitoring efforts18,19. Simplifying complex hydrogeological conditions in groundwater simulations further increases uncertainty20. Traditional methods based on meteorological and hydrological data and interpolation techniques struggle to capture large-scale drought conditions due to environmental heterogeneity and insufficient data21,22. Despite its usefulness, GRACE has limitations, such as its low spatial resolution (~ 350 km) and short data record, which reduce its effectiveness for long-term drought assessments23. In addition, only relying on a single variable, such as soil moisture, precipitation, or surface runoff, to construct various drought indices may not adequately or comprehensively reflect the actual drought conditions23. These issues highlight the need for higher-resolution data, better models, and comprehensive datasets to improve groundwater drought monitoring accuracy.

Machine learning is a crucial tool for addressing these challenges24 leveraging big data to improve the accuracy of large-scale drought monitoring and effectively capture the complex non-linear relationships essential for understanding drought phenomena25. Researchers have demonstrated the applicability of machine learning in drought monitoring by using random forest model26 to integrate meteorological and satellite data for constructing drought monitoring indices. By employing machine learning, GRACE satellite data can be downscaled to generate high-resolution groundwater storage estimates27. This approach has been proven effective in capturing detailed variations in water storage, thereby providing more refined data essential for groundwater drought research27. In another study focused on the Canadian Prairies, a high-resolution machine learning model based on the XGBoost algorithm was developed to analyze drought dynamics28. This model integrated key indicators such as the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), soil moisture, vegetation coverage, evapotranspiration (ET), and terrestrial water storage. The resulting model demonstrated substantial potential for operational drought monitoring, achieving an accuracy of 71.3%28.

A key challenge faced by machine learning models is their interpretability, specifically how environmental features influence the ability to predict groundwater drought. While global interpretability methods, such as the Gini impurity index, can assess the average importance of input features for model predictions, they fall short in explaining the impact of each feature on individual samples29. Recently, local interpretability methods have emerged to overcome this limitation, with LIME and SHAP being two such approaches30,31. However, LIME’s stability is relatively low, leading to significant variation in explanations31. In contrast, SHAP, which is based on game theory, offers greater mathematical accuracy and consistency30. SHAP breaks down global predictions into additive contributions of local features, ensuring alignment between global and local interpretations32. Therefore, in the framework of groundwater drought machine learning models, SHAP values are used as a local feature importance measure to analyze drought dynamics and understand the drivers of groundwater drought.

The West Liao River Plain (WLRP) is an important national base for grain production and livestock farming. Due to excessive reliance on groundwater for industrial, agricultural, and domestic purposes, groundwater reserve have significantly decreased, leading to land subsidence in some areas33. Due to being located in a semi-arid region, groundwater resources are highly influenced by climate changes and anthropogenic activities34. In recent years, the continuous decline in groundwater levels and the decreasing availability of groundwater resources have severely constrained the sustainable development of the local ecological environment and socio-economics. Due to the semi-arid climate and strong dependence of agriculture on groundwater irrigation, the WLRP is particularly prone to groundwater drought, making it an ideal area for developing and testing machine learning models for predicting groundwater drought. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are a next-generation of scenario frameworks developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to facilitate research on future climate change35 which describe different trajectories of future socioeconomic development. In this study, two specific SSP scenarios were used to project future groundwater drought in the WLRP: SSP2-4.5, which represents a pathway of intermediate socioeconomic vulnerability35 and SSP5-8.5, which describes a scenario characterized by rapid economic growth and extreme radiative forcing35.

The study aims to (1) establish a predictive and transparent machine learning model for understanding and forecasting groundwater drought events in WLRP, (2) conduct global and local feature importance analyses on the optimal model to identify the key determinants of groundwater drought and analyze their interactions with other feature variables by using SHAP analysis, and (3) predict future groundwater drought risks under two climate scenarios (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5). This research can promote the appropriate application of machine learning and provide early warning information for groundwater drought.

Materials and methods

Study area

The WLRP is located in the agro-pastoral transition zone of northeastern China (120.3°E-123.7°E, 42.5°N-44.9°N), with a basin area of 42,327 km², and is classified as a resource-scarce region36 (Fig. 1). Situated in a semi-arid region, the WLRP experiences a continental monsoon climate with significant interannual precipitation variability. The annual precipitation ranges from 350 to 400 mm, mostly concentrated in July and August, while the annual evaporation ranges from 1800 to 2000 mm, and the average annual temperature is 5.0 °C to 6.5 °C, with summer temperatures around 22 °C36. The region’s rich soil, formed by the sediments of the West Liao River and Xinkai River, provides excellent conditions for agriculture, making the WLRP an important grain and livestock production area and part of the global “Golden Corn Belt”33. However, severe dependence on groundwater for irrigation, combined with rapid population growth and economic development, has led to overexploitation of groundwater resources for decades, resulting in a persistent decline in groundwater levels33. Since 1980, surface water flow in the WLRP has steadily decreased, with complete cessation observed after 2000 37. By 2020, agricultural irrigation accounted for 75% of total water use, and cumulative groundwater depletion had reached critical levels33. This fertile plain has faced severe water resource constraints and drought issues. Therefore, the WLRP serves as a typical and representative study area for developing and validating machine learning models for groundwater drought prediction.

Location of the west liao river plain (WLRP) in inner mongolia autonomous region, china. (The map was created using ArcGIS, version 10.2; https://desktop.arcgis.com/zh-cn/desktop/index.html).

Groundwater drought labeling and feature selecting

The Standardized Groundwater Index (SGI) was used to identify groundwater drought events, following the methodology of Bloomfield and Marchant38. The SGI, derived from the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)39 assesses groundwater drought conditions, with values below zero indicating drought. Data for this study were sourced from 83 national monitoring wells across the study area, with observations from September 2018 to July 2022. Monthly average water levels were derived from daily measurements to calculate SGI values, using a distribution function fitted to the series of monthly average groundwater levels, then converted into a standard normal distribution (Figure S1).

To analyze factors influencing groundwater drought, relevant features were selected based on previous studies. Vegetation impact was represented by the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and land use (Land)40. Climate-related features included precipitation (Pre), temperature (Tmp), potential evapotranspiration (PET), and soil moisture (SM)41. Human activities were captured using the Human Footprint (HFP) dataset and population density (POP)42. Groundwater storage anomaly (GWSA) and elevation (DEM) were also included as indicators of groundwater response27.

Meteorological drought indices, particularly the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), reflect the cumulative impact of drought conditions on groundwater. The SPEI is calculated at different time scales, such as 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, to represent the cumulative impact of drought over different durations43. In this study, SPEI values at 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month time scales (SPEI01, SPEI03, SPEI06, SPEI12, and SPEI24) were derived using precipitation and potential evapotranspiration data43 to capture both short-term meteorological variability and long-term cumulative drought effects. Shorter time scales (SPEI01, SPEI03) are sensitive to immediate moisture deficits, whereas longer time scales (SPEI12, SPEI24) account for prolonged drought conditions, which are more relevant to groundwater systems due to their slower response times43. This multi-scale meteorological drought indices enables a comprehensive analysis of how meteorological droughts propagate into groundwater droughts over varying durations. Data sources and distributions of all features are shown in Figure S2 and Table S1.

Machine learning modeling

Figure 2 illustrates the data modelling and analysis approach for the detailed study of groundwater drought. Eight machine learning models (eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Logistic Regression (LR), Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), and Support Vector Machine (SVM) from Scikit-learn, version 1.2.0) were used. Hyperparameter optimization was performed using Grid Search Cross-Validation (GSCV) and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA). GSCV employed grid search with 5-fold cross-validation, while SSA, inspired by sparrow foraging behavior, efficiently identified optimal solutions44. Model performance was evaluated using AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, with details in the supplementary materials. SHAP values from the optimal model analyzed feature impact, explaining the marginal contribution of 15 environmental variables to groundwater drought. This method provided insights into the primary factors influencing groundwater drought and the decision-making process of the machine learning models.

Results and discussions

Model development and assessment

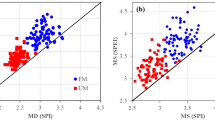

A total of 3,474 groundwater level observations were collected between July 2018 and September 2022. The Standardized Groundwater Drought Index (SGI) was used to identify 1,710 drought and 1,764 non-drought samples (Figure S3). The dataset was split into 80% training (2,779 samples) and 20% testing (695 samples), stratified by the binary output variable. Eight machine learning models were optimized using GSCV and the SSA based on the training set. Figure 3 presents the ROC curves for these models, while Table S2 provides a detailed comparison of AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Figures S4 and S5 further present the confusion matrices and calibration curves, providing a comprehensive evaluation of classification performance.

The top-performing models under GSCV were XGBoost (AUC: 0.898), LightGBM (0.880), and RF (0.829). Under SSA optimization, XGBoost achieved the highest AUC of 0.922, followed by LightGBM (0.897) and RF (0.852), reflecting a significant improvement in discriminative power under SSA optimization. F1 scores were also assessed, with XGBoost, LightGBM, and RF achieving scores above 0.7 under GSCV, and DT joining them under SSA. Notably, SSA-optimized XGBoost achieved an F1 score of 0.84, surpassing its GSCV counterpart by 0.03. The F1 score, as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, indicates the model’s ability to accurately identify drought events while minimizing false positives. High precision reduces unnecessary management actions, while high recall ensures timely drought warnings, crucial for effective groundwater management and water allocation. Details on the analysis of the AUC and F1 scores can be found in the supporting information.

From a performance standpoint, the top-performing models include XGBoost, LightGBM, RF, and DT, all of which are based on tree-based classification methods. Among these, RF demonstrates significant potential to surpass traditional regression models, such as Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), particularly when handling complex non-linear relationships45. As more advanced tree-based models, XGBoost and LightGBM have been optimized with gradient boosting techniques to enhance model efficiency and predictive performance, especially for large-scale datasets. In groundwater drought prediction, dichotomization reduces noise from random anthropogenic inputs, potentially improving model performance by balancing noise reduction with information loss.

XGBoost optimized with the SSA algorithm demonstrated the best performance among the models evaluated, achieving significant improvements in AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score compared to GSCV-optimized XGBoost (Figure S6). The DeLong test (Table S3) confirmed that the ROC curves of SSA-optimized XGBoost were statistically different from those of other models (p < 0.05), indicating the effectiveness of SSA in enhancing predictive power. Meta-heuristic algorithms like SSA are highly effective for hyperparameter optimization, and have been applied successfully in areas such as hydrological management and disaster prevention46,47.XGBoost’s scalability, efficiency, and accuracy, along with its insensitivity to hyperparameter choices48 make it particularly suitable for addressing complex non-linear relationships, where linear models often fall short49,50,51. XGBoost also integrates seamlessly with Tree SHAP, allowing efficient computation of SHAP values for model interpretability52.

The SSA-optimized XGBoost (SSA-XGBoost) was selected for SHAP analysis to evaluate the influence of various factors on groundwater drought. A SHAP heatmap (Figure S7) highlighted the contribution of different features, illustrating distinct feature clusters and their interactions. In contrast, linear regression models produced suboptimal results (Figure S8), failing to accurately represent the relationship between features such as land use (Land) and human footprint (HFP) with drought conditions.

SHAP interpretation and global feature importance

Features importance ranking

SHAP analysis of the SSA-XGBoost model (Fig. 4a) ranks the importance of 15 features in predicting groundwater drought, with marginal contributions represented as SHAP values. Figure 4b shows the relative importance, and Figure S9 presents the absolute mean SHAP values for each feature. The top six predictors are SPEI12, SPEI24, precipitation (Pre), soil moisture (SM), the human footprint (HFP), and the digital elevation model (DEM). The GSCV-XGBoost model also highlighted the importance of these features, confirming their significance in predicting groundwater drought (Figure S9). According to Fig. 4b, SPEI12 (14.8%) and SPEI24 (10.5%) play critical roles in predicting groundwater drought events in WLRP, together accounting for 25.3% of the total contribution. As the two most influential factors, they reflect the significant impact of long-term meteorological drought on groundwater drought. Human-related factors, including the HFP and population (POP), contribute a combined 14.3%, second only to SPEI12. Pre accounts for 10.3%, while temperature (Tmp) accounts for 6%, with their combined contribution totaling 16.3%, which is slightly less than the combined contribution of long-term meteorological drought indices (SPEI12 and SPEI24). SPEI03 and SPEI06 contribute 4% and 3.6%, respectively, indicating that short-term meteorological drought has a relatively limited impact on groundwater drought. SM and DEM rank fourth and sixth in terms of contribution, accounting for 8.5% and 7.4%, respectively.

Meteorological droughts, characterized by precipitation deficits and increased evapotranspiration, often precede groundwater droughts by reducing soil moisture and recharge53. The human footprint (HFP) reflects anthropogenic impacts that intensify groundwater drought27. Excessive groundwater extraction, though often used to meet water demand during droughts, can exacerbate groundwater depletion54. Precipitation replenishes groundwater storage, while topographical features like DEM are essential for defining recharge areas55. Soil moisture plays a critical role in terrestrial water storage and groundwater recharge56. Notably, long-term SPEI indices (SPEI12 and SPEI24) exhibited the highest global interpretability in predicting groundwater drought in the WLRP.

Response of groundwater drought to meteorological drought

The spatial distribution of groundwater drought in the WLRP from 2008 to 2022 was analyzed, and the affected areas were quantified (Figure S10). Figure 5 shows that the delayed response of groundwater drought in the WLRP to meteorological drought exceeds 12 months. Severe droughts occurred in 2008 and 2009, corresponding to an average hydrological year and a drought year, respectively (Fig. 5b). Drought years are typically accompanied by reduced precipitation, leading to severe meteorological drought57. Subsequently, the area affected by groundwater drought increased significantly, with over 70% of the region still impacted even in the following wet year. This suggests that large-scale groundwater drought not only directly responds to ongoing drought conditions but also exhibits a lagged response to severe meteorological drought from the previous year.

In contrast, the extent of groundwater drought decreased significantly in 2013, 2019, and 2022, mainly due to increased precipitation in the preceding year. Under wet conditions, increased precipitation effectively mitigates the transition from meteorological drought to groundwater drought58. This confirms the strong hydrological link between precipitation and groundwater recharge observed in recent years. When meteorological drought occurs, reduced precipitation and increased evapotranspiration lead to insufficient soil moisture, which decreases groundwater recharge and eventually results in groundwater drought59,60.

In the WLRP, SPEI12 and SPEI24 are key variables in predicting groundwater drought events using the XGBoost model, with a combined contribution of 25.28%. As shown in Fig. 4b, SPEI12 accounts for 14.8% and SPEI24 for 10.05% of the total contribution. These features highlight the significant impact of meteorological drought on groundwater drought, particularly through the response of soil moisture in different aquifer layers. This aligns with the mechanism of hydrological drought propagation, where reduced soil moisture, changes in meteorological signals (e.g., decreased rainfall), and reduced groundwater recharge lead to a decline in groundwater levels61. The spatiotemporal characteristics of drought signals evolve within the water cycle, resulting in the delayed onset of groundwater drought, while dampening the immediate effects of meteorological drought62.

Studies have shown that the hydrological responses of groundwater and meteorological droughts differ significantly across space and time due to aquifer heterogeneity, climate variability, and human activities63,64. Typically, a 12-month propagation time corresponds to mid-layer aquifers, while a 24-month time scale is associated with deeper aquifers65. The weaker connection between precipitation and deep aquifer groundwater fluctuations extends the propagation time compared to mid-layer aquifers. In contrast, shallow aquifers respond more quickly to meteorological drought, typically within 3–6 months65. As indicated in Fig. 4b, SPEI03 and SPEI06 contribute only 4% and 3.6%, respectively, suggesting that short-term meteorological droughts have a relatively minor effect on groundwater drought. This further indicates that groundwater drought in WLRP primarily occurs in mid- and deep-layer aquifers. Additionally, soil moisture is the fourth most significant factor influencing groundwater drought, contributing 8.50% to the overall variance (Fig. 5b). This highlights the critical role of the mid-to-deep soil layers in groundwater recharge within the WLRP56.

One of the main advantages of SHAP is its ability to compute local importance for each value of every model variable32. As shown in Fig. 4a, the local SHAP value of SPEI12 exhibits an almost monotonically decreasing relationship with its actual value. This indicates that as SPEI12 decreases, the SHAP value increases, enhancing the model’s prediction of drought events. SPEI24, the second most important variable, shows a similar influence, indicating that cumulative drought conditions over 12 to 24 months play a crucial role in groundwater drought occurrence in the WLRP. This finding aligns with Liu et al.53 who reported that the average time for meteorological drought to propagate into groundwater drought in the Northern Hemisphere is 14.41 months, and that this propagation time is closely related to changes in precipitation and soil moisture66.

Role of anthropogenic factors in shaping groundwater drought

Previous studies indicate that groundwater drought responds to meteorological drought over periods ranging from several months to years, with severe meteorological droughts most likely leading to groundwater drought59,60,62. However, Van Loon et al.67 highlighted that human activities, such as groundwater extraction, agricultural irrigation, and urbanization, significantly influence groundwater drought by altering hydrological processes, including evapotranspiration, infiltration, and runoff. In the WLRP, despite efforts like ecological water replenishment and inter-basin transfers, over-extraction of groundwater remains a major driver of drought. Figure 4b shows that human-related factors, such as the Human Footprint (HFP) and population density (POP), contribute 14.32% to the model, second only to SPEI12. This underscores the role of human activities in prolonging and intensifying groundwater drought, particularly in mid- and deep-layer aquifers65.

Since the 1980 s, agricultural irrigation in the WLRP has increasingly shifted from surface water to groundwater, with annual extraction reaching approximately 3.70 km³ by 2015, accounting for 82% of total groundwater use33. This over-reliance on groundwater, driven by the expansion of irrigated areas, is a key contributor to the declining water table and groundwater drought. Urbanization also exacerbates groundwater drought by altering surface characteristics, reducing infiltration, and increasing runoff68,69. During drought periods, excessive groundwater extraction for urban water demand further intensifies the situation40.

The WLRP’s intense interactions between human activities and natural systems often prevent meteorological drought from directly leading to groundwater drought. This explains why human activity-related factors, such as HFP and POP, are significant contributors to groundwater drought. During the rainy season (May to August), groundwater drought persists despite sufficient precipitation, largely due to excessive extraction for agricultural irrigation36,70. This imbalance between water supply and demand intensifies drought conditions, particularly in irrigated areas. In contrast, non-irrigated regions are more vulnerable to precipitation deficits due to the lack of regular groundwater extraction and irrigation71.

Robust association of groundwater drought with precipitation

Precipitation has always been one of the key sources of groundwater recharge and plays a crucial role in predicting groundwater drought. As shown in Fig. 4, precipitation ranks third, following long-term meteorological drought indices, contributing 10.3% to the model’s prediction accuracy. From Fig. 6a, it can be observed that the local SHAP values for precipitation increase almost monotonically with rising precipitation levels, indicating a straightforward positive correlation between precipitation and binarized groundwater drought. Notably, precipitation only has a positive effect on mitigating groundwater drought when it exceeds 50 mm, further confirming that precipitation is a reliable predictor of groundwater drought. More importantly, similar trends are evident in the SHAP dependence plots for SPEI12 (Fig. 6b) and SPEI24 (Fig. 6c), demonstrating that these two long-term meteorological drought indicators are also reliable predictors of groundwater drought. The stable and consistent distribution of local SHAP values for precipitation, SPEI12, and SPEI24 around their average values suggests that their influence on the model remains steady, with no abrupt changes in SHAP values caused by minor fluctuations in the variables. This indicates that the model responds smoothly to changes in these variables, ensuring stable prediction outcomes.

Moreover, SHAP values provide local importance for each individual value of these variables, and the monotonic relationships observed suggest that their contribution to the model’s predictions is largely dependent on their own values rather than interactions with other features. All three variables exhibit strong robustness, as they are not sensitive to small variations and maintain a monotonic relationship with groundwater drought conditions. Minor changes around their mean values do not significantly alter the SHAP values, indicating that the model assigns consistent weight to these variables. Their sustained impact on the model’s performance demonstrates that they are key drivers of the target outcome (groundwater drought), contributing to the overall robustness of the model. The monotonicity of precipitation, SPEI12, and SPEI24 ensures their continued influence on drought prediction and underscores their role as key drivers of model performance. The environmental significance of these variables further enhances their robustness, as they represent stable, long-term indicators of drought conditions.

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 7, the non-monotonic distribution of local SHAP values for Temperature, SPEI01, SPEI03, and SPEI06 indicates that these variables exhibit poor robustness. Their high sensitivity to fluctuations, coupled with an unstable relationship with the target variable, suggests that their contribution to the model’s predictions is inconsistent. Moreover, potential interactions with other environmental factors further complicate their predictive influence. This lack of stability leads to unpredictable prediction outcomes, thereby reducing the overall robustness of these variables in the model. For a detailed analysis, please refer to the supplementary materials.

A notable phenomenon is observed in 6a, where increased precipitation correlates with more severe groundwater drought in the WLRP. Detecting and quantifying feature interactions is crucial in machine learning29 as individual feature effects can be misleading when interactions are significant, especially for complex systems like groundwater drought prediction in the WLRP. To better understand this, the interaction between precipitation and various meteorological features is further analyzed. In Fig. 8a, the combination of precipitation and temperature significantly influences the occurrence of groundwater droughts. In particular, as precipitation increases (100 mm to 250 mm) and temperature increases (20 °C to 25 °C), the probability of groundwater drought increases. There are two main reasons for this phenomenon. First, this period corresponds to the summer growing season in the WLRP, when agricultural irrigation demand peaks, leading to intensive groundwater extraction. Second, the more frequent occurrence of groundwater droughts is not only due to a lack of rainfall, but also to an increase in temperature. Higher temperatures increase evaporation from the soil above the phreatic surface, especially from the capillary fringe, as noted by Bloomfield et al.72. Furthermore, when the intensity of summer precipitation is very high, much of the water becomes runoff, contributing little to aquifer recharge. Conversely, when precipitation is less intense, vegetation type and coverage play a critical role in determining the amount of recharge reaching the aquifers. Even dry soil conditions can negatively impact permeability, further affecting recharge volumes73.

The role of meteorological drought in the impact of precipitation on groundwater drought is illustrated in Fig. 8b and f. These figures clearly show that groundwater drought in April and June is closely related to lower precipitation levels (approximately 50–100 mm), highlighting the high sensitivity of the groundwater system to short-term meteorological conditions, especially early in the growing season when agricultural water demand begins to rise. During this period, insufficient rainfall, coupled with increasing irrigation needs, intensifies groundwater drought, making the influence of meteorological drought on groundwater drought more pronounced at different time scales. In Fig. 8c and d, seasonal meteorological drought (SPEI03 and SPEI06) is particularly prominent in driving groundwater drought. Negative values of SPEI03 and SPEI06, representing three- and six-month drought periods, are strongly associated with higher SHAP values, confirming that short- to medium-term meteorological droughts are the main drivers of summer groundwater drought. This rapid transmission from meteorological drought to groundwater drought is particularly evident in the WLRP and is consistent with findings from previous research66. The relatively short transmission time (approximately 3 to 6 months) can be attributed to the combination of high temperatures and intensive agricultural activity during the summer growing season, which accelerates groundwater depletion. This underscores the vulnerability of the region’s groundwater resources to seasonal drought. In contrast, the lower SHAP values associated with SPEI12 in Fig. 8e and f indicate that the groundwater system in the WLRP is more sensitive to short-term seasonal droughts than to long-term droughts lasting a year. The influence of two-year meteorological droughts (SPEI24) on short-term groundwater drought patterns is relatively weak, suggesting that while long-term drought may impact overall groundwater trends, its direct connection to groundwater drought during critical agricultural periods is less significant. This also shows that the impact of meteorological drought on groundwater drought has obvious seasonal characteristics. For example, changes in demand for domestic water and agricultural irrigation will affect the occurrence of groundwater drought in different ways at different times of the year.

Future groundwater drought risk in the WLRP

Given the excellent performance of the SSA-XGBoost model in the earlier analysis, we utilized this model to predict groundwater drought in the WLRP under future climate scenarios from 2023 to 2100. Groundwater drought scenarios from 2023 to 2100 were analyzed using precipitation and temperature datasets from the BCC-CSM2-MR model under two Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs): SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.535. SSP2-4.5 represents moderate socioeconomic vulnerability, while SSP5-8.5 depicts high economic growth with extreme radiative forcing35. Model outputs were downscaled and bias-corrected to better reflect future climate trends in the study area. Assuming human activities and land use remain constant, the affected area of groundwater drought is projected to expand significantly under both SSP scenarios.As shown in Fig. 9a, under SSP2-4.5, groundwater drought is expected to affect more than 70%, 80%, and 90% of the area for 67.9%, 51.3%, and 28.2% of the years, respectively. These proportions rise to 70.5%, 59.0%, and 33.33% under SSP5-8.5, indicating a substantial increase in drought risk, especially under SSP5-8.5.

(a) Ratios of groundwater drought under two climate scenarios for historical periods and the future. (b) and (c) Correlation of groundwater drought ratios with SPEI12 under two SSP scenarios. (d) Box-plots of annual mean ratios of groundwater drought in the WLRP under two SSP scenarios for short-term (2023–2050, ST), medium-term (2050–2075, MT), and long-term (2075–2100, LT) periods.

A strong negative correlation exists between the groundwater drought area and the 12-month scale meteorological drought index (SPEI12), as illustrated in Fig. 9b and c, with correlation coefficients of −0.87 for SSP2-4.5 and − 0.91 for SSP5-8.5, emphasizing the influence of meteorological drought on groundwater conditions. Figure 9d shows that under SSP2-4.5, the WLRP is projected to remain relatively wet until 2050, with drought conditions worsening afterward, particularly post-2075. In contrast, under SSP5-8.5, severe drought is expected throughout the entire forecast period. Over the next 78 years, precipitation is not projected to change significantly, with considerable uncertainty in estimates under both scenarios (Figure S11a). However, temperature shows a clear upward trend, with a more pronounced increase after 2040 under SSP5-8.5 (Figure S11b). Rising temperatures are expected to increase evapotranspiration demand, reducing groundwater infiltration regardless of rainfall patterns. Consequently, even stable precipitation levels may not prevent reduced aquifer recharge, underscoring the impact of climate warming on groundwater resources74. In the past decade, sudden drought events have become a notable issue due to climate warming and increased human activity75.

Current forecasting methods rely on regression models using historical meteorological drought indices and groundwater drought indices. However, these approaches struggle to account for the non-linear relationship between meteorological and groundwater drought and uncertainties from increased CO2 concentrations and changing evapotranspiration76. Machine learning models, by directly incorporating climate variables such as precipitation and temperature, can capture these complex relationships more effectively, offering more reliable predictions for groundwater drought17.

Limitations

Our study explores the relationship between meteorological and groundwater drought in the WLRP using a novel machine learning framework. However, the model mainly focuses on meteorological and anthropogenic factors, without fully considering hydrogeological conditions. Factors such as aquifer lithology77 soil characteristics78 slope and aspect79 significantly influence groundwater recharge and drought occurrence, but have not been included in the current analysis. For areas with complex hydrogeological environments, the variables like aquifer lithology, soil characteristics, slope and aspect are included into the machine learning model can help better capture the drivers of groundwater drought and improve predictive accuracy. Secondly, when predicting future climate scenarios, our study assumes human activity and land use are static, with a focus on the impacts of climate change impacts. However, the dynamic changes of these factors could significantly affect groundwater drought risk. Future studies could simulate dynamic scenarios of human activities and land use to evaluate their impacts on groundwater drought risk under changing conditions, thus better capturing the combined effects of climatic and anthropogenic drivers.

Conclusion

Groundwater drought seriously affects the ecological environment and sustainable socio-economic development in areas that rely on groundwater. Eight machine learning models were employed to predict groundwater drought in WLRP, resulting in the following key findings:

-

1)

The XGBoost model optimized by SSA performed better than other models, achieving an AUC of 0.92, accuracy of 0.84, and F1-score of 0.84. Compared to GSCV, SSA optimization improved key metrics by 2–4%, enhancing predictive capability and interpretability.

-

2)

The SHAP global feature importance analysis determined that SPEI12 and SPEI24 are the most influential predictors, contributing 14.8% and 10.5% to the model’s predictions, respectively. This indicates that 12- and 24-month meteorological droughts have a strongly impact on groundwater levels.

-

3)

Groundwater drought lagged behind meteorological drought by 12–24 months, affecting mid- and deep-layer aquifers and persisting even in wet years. Soil moisture contributed 8.5% to groundwater recharge, while excessive extraction and urbanization exacerbated drought conditions.

-

4)

SHAP interaction analysis revealed that the probability of groundwater drought increased with rising precipitation (100–250 mm) and temperature (20–25 °C), with short- to medium-term meteorological droughts driving groundwater drought during summer.

-

5)

Future scenarios under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 indicate an increased risk of groundwater drought, particularly under extreme climate conditions (SSP5-8.5), with expected impacts starting earlier and lasting longer.

Unlike traditional methods, machine learning effectively captures the complex non-linear relationships between climate variables and groundwater levels, providing more reliable predictions. This study presents a high-precision model for understanding and predicting groundwater drought using state-of-the-art machine learning and SHAP interpretability analysis. The model’s applicability to large-scale drought monitoring systems enables stakeholders to mitigate current droughts, make informed decisions, and recognize early warning signals for future groundwater droughts.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vu, C. H., Nguyen, B. Q., Tran, T. N. D., Vo, D. N. & Arshad, A. Climate change-driven hydrological shifts in the Kon-Ha Thanh river basin. Water 16, 3389 (2024).

Guo, M., Yue, W., Wang, T., Zheng, N. & Wu, L. Assessing the use of standardized groundwater index for quantifying groundwater drought over the conterminous US. J. Hydrol. 598, 126227 (2021).

Nguyen, B. Q., Van Binh, D., Tran, T. N. D., Kantoush, S. A. & Sumi, T. Response of streamflow and sediment variability to cascade dam development and climate change in the Sai Gon dong Nai river basin. Clim. Dyn. 62, 7997–8017 (2024).

Tran, T. N. D. & Lakshmi, V. Enhancing human resilience against climate change: assessment of hydroclimatic extremes and sea level rise impacts on the Eastern shore of virginia, united States. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174289 (2024).

Tran, T. N. D. et al. Investigating the future flood and drought shifts in the transboundary Srepok river basin using CMIP6 projections. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs Remote Sens. 17, 7516–7529 (2024).

Eltahir, E. A. B. & Yeh, P. J. F. On the asymmetric response of aquifer water level to floods and droughts in Illinois. Water Resour. Res. 35, 1199–1217 (1999).

Van Lanen, H. A. J. & Peters, E. Definition, effects and assessment of groundwater droughts. In Drought and Drought Mitigation in Europe Vol. 14 (eds Vogt, J. V. & Somma, F.) 49–61 (Springer Netherlands, 2000).

Lange, B., Holman, I. & Bloomfield, J. P. A framework for a joint hydro-meteorological-social analysis of drought. Sci. Total Environ. 578, 297–306 (2017).

Thomas, B. F. et al. GRACE groundwater drought index: evaluation of California central Valley groundwater drought. Remote Sens. Environ. 198, 384–392 (2017).

Tran, T. N. D., Tapas, M. R., Do, S. K., Etheridge, R. & Lakshmi, V. Investigating the impacts of climate change on hydroclimatic extremes in the Tar-Pamlico river basin, North Carolina. J. Environ. Manage. 363, 121375 (2024).

Tran, T. N. D. et al. Robustness of gridded precipitation products for Vietnam basins using the comprehensive assessment framework of rainfall. Atmos. Res. 293, 106923 (2023).

Tran, T. N. D., Nguyen, B. Q., Grodzka-Łukaszewska, M., Sinicyn, G. & Lakshmi, V. The role of reservoirs under the impacts of climate change on the Srepok river basin, central highlands of Vietnam. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1304845 (2023).

Badawy, A. et al. Floods of egypt’s nile in the 21st century. Sci. Rep. 14, 27031 (2024).

Tapas, M. R. et al. A methodological framework for assessing sea level rise impacts on nitrate loading in coastal agricultural watersheds using SWAT+: a case study of the Tar-Pamlico river basin, North carolina, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 951, 175523 (2024).

Nguyen, B. Q. et al. Response of Hydrological To Anthropogenic Activities in a Tropical Basinin 269–278 (Vienna, 2013).

Liu, Q. et al. Characteristics of groundwater drought and its correlation with meteorological and agricultural drought over the North China plain based on GRACE. Ecol. Indic. 161, 111925 (2024).

Secci, D., Tanda, M. G., D’Oria, M., Todaro, V. & Fagandini, C. Impacts of climate change on groundwater droughts by means of standardized indices and regional climate models. J. Hydrol. 603, 127154 (2021).

Zhu, Q. & Zhang, H. Groundwater drought characteristics and its influencing factors with corresponding quantitative contribution over the two largest catchments in China. J. Hydrol. 609, 127759 (2022).

Do, S. K. et al. Assessing terrestrial water storage variations in Afghanistan using GRACE and FLDAS-central Asia data. J. Hydrol. : Reg. Stud. 55, 101906 (2024).

Li, B. & Rodell, M. Evaluation of a model-based groundwater drought indicator in the conterminous U.S. J. Hydrol. 526, 78–88 (2015).

Han, Z. et al. Assessing GRACE-based terrestrial water storage anomalies dynamics at multi-timescales and their correlations with teleconnection factors in Yunnan province, China. J. Hydrol. 574, 836–850 (2019).

Long, D. et al. Drought and flood monitoring for a large karst plateau in Southwest China using extended GRACE data. Remote Sens. Environ. 155, 145–160 (2014).

Thomas, A. C., Reager, J. T., Famiglietti, J. S. & Rodell, M. A GRACE-based water storage deficit approach for hydrological drought characterization. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1537–1545 (2014).

Agarwal, V. et al. Machine learning based downscaling of GRACE-estimated groundwater in central valley, California. Sci. Total Environ. 865, 161138 (2023).

Kumari, S., Kumar, D., Kumar, M. & Pande, C. B. Modeling of standardized groundwater index of Bihar using machine learning techniques. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C. 130, 103395 (2023).

Chen, L., He, Q., Liu, K., Li, J. & Jing, C. Downscaling of GRACE-derived groundwater storage based on the random forest model. Remote Sens. 11, 2979 (2019).

Ali, S. et al. Constructing high-resolution groundwater drought at spatio-temporal scale using GRACE satellite data based on machine learning in the indus basin. J. Hydrol. 612, 128295 (2022).

Mardian, J., Champagne, C., Bonsal, B. & Berg, A. A machine learning framework for predicting and Understanding the Canadian drought monitor. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR033847 (2023).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global Understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Preprint At. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874 (2017).

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., Guestrin, C. & ‘Why Should, I. Trust You?’: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 1135–1144ACM, San Francisco California USA, (2016).

Li, L. et al. Interpretable tree-based ensemble model for predicting beach water quality. Water Res. 211, 118078 (2022).

Zhong, Y. et al. Groundwater depletion in the West Liaohe river basin, China and its implications revealed by GRACE and in situ measurements. Remote Sens. 10, 493 (2018).

Zhao, H. et al. Research on the evolution characteristics of future climate change in West Liao river basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut R. 29, 509–517 (2022).

Kriegler, E. et al. Fossil-fueled development (SSP5): an energy and resource intensive scenario for the 21st century. Global Environ. Change. 42, 297–315 (2017).

Jiang, W. et al. Exploring spatial-temporal driving factors for changes in multiple ecosystem services and their relationships in West Liao river basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166716 (2023).

Gao, M. et al. Spatial and Temporal variations of vegetation water use efficiency and its response to climate change and human activities in the West Liao river plain, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1176131 (2023).

Bloomfield, J. P. & Marchant, B. P. Analysis of groundwater drought Building on the standardised precipitation index approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 4769–4787 (2013).

McKee, T.B., Doesken, N.J. and Kleist, J. The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales. 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, 179–184 (1993).

Han, Z. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration on groundwater drought in the loess plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 591, 125566 (2020).

Li, B., Rodell, M., Sheffield, J., Wood, E. & Sutanudjaja, E. Long-term, non-anthropogenic groundwater storage changes simulated by three global-scale hydrological models. Sci. Rep. 9, 10746 (2019).

Liu, P. W. et al. Groundwater depletion in california’s central Valley accelerates during megadrought. Nat. Commun. 13, 7825 (2022).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S. & López-Moreno, J. I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 23, 1696–1718 (2010).

Xue, J. & Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: sparrow search algorithm. Sys Sci. Control Eng. 8, 22–34 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Improving the robustness of beach water quality modeling using an ensemble machine learning approach. Sci. Total Environ. 765, 142760 (2021).

Khosravi, K., Panahi, M. & Tien Bui, D. Spatial prediction of groundwater spring potential mapping based on an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and metaheuristic optimization. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 4771–4792 (2018).

Liu, R. et al. Spatial prediction of groundwater potentiality using machine learning methods with grey Wolf and sparrow search algorithms. J. Hydrol. 610, 127977 (2022).

Gao, L. & Ding, Y. Disease prediction via bayesian hyperparameter optimization and ensemble learning. BMC Res. Notes. 13, 205 (2020).

Wu, J., Chen, X., Yao, H. & Zhang, D. Multi-timescale assessment of propagation thresholds from meteorological to hydrological drought. Sci. Total Environ. 765, 144232 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Non-linear relationship of hydrological drought responding to meteorological drought and impact of a large reservoir. J. Hydrol. 551, 495–507 (2017).

Zhou, Z. et al. Investigating the propagation from meteorological to hydrological drought by introducing the nonlinear dependence with directed information transfer index. Water Resour. Res. 57, eWR030028 (2021). (2021).

Yang, J. Fast TreeSHAP: accelerating SHAP value computation for trees. Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2109.09847

Liu, Y., Shan, F., Yue, H., Wang, X. & Fan, Y. Global analysis of the correlation and propagation among meteorological, agricultural, surface water, and groundwater droughts. J. Environ. Manage. 333, 117460 (2023).

Castle, S. L. et al. Groundwater depletion during drought threatens future water security of the Colorado river basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5904–5911 (2014).

Mirosław-Świątek, D., Kiczko, A., Szporak-Wasilewska, S. & Grygoruk, M. Too wet and too dry? Uncertainty of DEM as a potential source of significant errors in a model-based water level assessment in riparian and mire ecosystems. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 25, 547–562 (2017).

Qing, Y., Wang, S., Yang, Z. L. & Gentine, P. Soil moisture – atmosphere feedbacks have triggered the shifts from drought to pluvial conditions since 1980. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 254 (2023).

Tayfur, G. Discrepancy precipitation index for monitoring meteorological drought. J. Hydrol. 597, 126174 (2021).

Schreiner-McGraw, A. P. & Ajami, H. Delayed response of groundwater to multi-year meteorological droughts in the absence of anthropogenic management. J. Hydrol. 603, 126917 (2021).

Fawen, L., Manjing, Z., Yong, Z. & Rengui, J. Influence of irrigation and groundwater on the propagation of meteorological drought to agricultural drought. Agric. Water Manag. 277, 108099 (2023).

Han, Z. et al. Long-chain propagation pathways from meteorological to hydrological, agricultural and groundwater drought and their dynamics in China. J. Hydrol. 625, 130131 (2023).

Peters, E., Torfs, P. J. J. F., Van Lanen, H. A. J. & Bier, G. Propagation of drought through groundwater—a new approach using linear reservoir theory. Hydrolo Processes. 17, 3023–3040 (2003).

Zhang, H., Ding, J., Wang, Y., Zhou, D. & Zhu, Q. Investigation about the correlation and propagation among meteorological, agricultural and groundwater droughts over humid and arid/semi-arid basins in China. J. Hydrol. 603, 127007 (2021).

Cui, L. et al. Spatiotemporal variation characteristics of droughts and their connection to climate variability and human activity in the Pearl river basin, South China. Water 15, 1720 (2023).

Fu, J. et al. Separating the impact of climate change and human activities on the connection between meteorological and hydrological drought. Hydrol. Processes. 38, e15258 (2024).

Gong, R. et al. Characterization and propagation from meteorological to groundwater drought in different aquifers with multiple timescales. J. Hydrol. : Reg. Stud. 45, 101317 (2023).

Han, Z. et al. Propagation dynamics from meteorological to groundwater drought and their possible influence factors. J. Hydrol. 578, 124102 (2019).

Van Loon, A. F. et al. Drought in the anthropocene. Nat. Geosci. 9, 89–91 (2016).

Olarinoye, T., Foppen, J. W., Veerbeek, W., Morienyane, T. & Komakech, H. Exploring the future impacts of urbanization and climate change on groundwater in arusha, Tanzania. Water Int. L. 45, 497–511 (2020).

Patra, S., Sahoo, S., Mishra, P. & Mahapatra, S. C. Impacts of urbanization on land use /cover changes and its probable implications on local climate and groundwater level. J. Urban Manag. 7, 70–84 (2018).

Gao, Z., He, J., Dong, K. & Li, X. Trends in reference evapotranspiration and their causative factors in the West Liao river basin, China. Agric. Meteorol. 232, 106–117 (2017).

Niu, J. et al. Environmental burdens of groundwater extraction for irrigation over an inland river basin in Northwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 222, 182–192 (2019).

Bloomfield, J. P., Marchant, B. P. & McKenzie, A. A. Changes in groundwater drought associated with anthropogenic warming. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 1393–1408 (2019).

Singh, V. P. et al. Handbook of Applied Hydrology. McGraw Hill Professional, New York, (2016).

Hua, S. et al. How to manage future groundwater resource of China under climate change and urbanization: an optimal stage investment design from modern portfolio theory. Water Res. 85, 31–37 (2015).

Christian, J. I. et al. Global distribution, trends, and drivers of flash drought occurrence. Nat. Commun. 12, 6330 (2021).

Hulme, M. WIREs climate change after 4 years: an editorial essay. WIREs Clim. Change. 5, 1–5 (2014).

Memon, A. et al. Estimation of groundwater potential using GIS modeling in Kohistan region Jamshoro district, Southern indus basin, sindh, Pakistan (a case study). Acta Geophys. 68, 155–165 (2020).

Smith, A. P. et al. Shifts in pore connectivity from precipitation versus groundwater rewetting increases soil carbon loss after drought. Nat. Commun. 8, 1335 (2017).

Arya, V. & Rao, M. S. Groundwater recharge potential index and artificial groundwater recharge in the alluvial soils of the middle Ganga basin. Discov Appl. Sci. 6, 367 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The research was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2503001) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 42177078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.G. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, and conducted validation, formal analysis, and investigation. Z.G. also wrote the original draft, reviewed and edited the manuscript, created visualizations, and developed the necessary software. C.S. contributed to the conceptualization, provided resources, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and managed the project administration and funding acquisition. X.X. contributed to the methodology, validation, funding acquisition, project administration, and manuscript review and editing. W.G. was responsible for investigation, funding acquisition, and project administration. H.P. and L.Y. supported the investigation, funding acquisition, and project administration. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gan, Z., Xie, X., Su, C. et al. Understanding the evolutionary processes and causes of groundwater drought using an interpretable machine learning model. Sci Rep 15, 20981 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05316-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05316-2