Abstract

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have gained a substantial attention for their transformative potential, with prior research predominantly focusing on end-user perceptions and autonomous functions. In contrast, other critical factors—such as component technologies and sociotechnical concerns—have received relatively limited attention. To address this gap, we employ a state-of-the-art topic modeling approach to empirically investigate the multifaceted public perceptions of AVs, with particular emphasis on battery technologies as an enabling component. Using BERTopic, we analyze 11,708 news articles on AVs published between 2002 and 2021, retrieved from the ProQuest ABI/INFORM database. Among the 45 publicly discussed issues identified, we categorize them into six dimensions based on the sociotechnical regime framework. A focused analysis of battery-related content reveals 15 recurrent themes, which are further classified into three dimensions. As discussed in prior research, issues such as safety and technical performance remain central in public perceptions. We further revealed the infrastructural and institutional concerns being publicly discussed. These results, recognizing the publicly perceived sociotechnical factors, underscore the importance of considering both technological and non-technological factors in the public perception of AVs and suggest new directions for future research and policymaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AVs are expected to have noteworthy potential to reshape the transportation industry by significantly enhancing user experiences, safety, and convenience1,2,3,4. Given that the direction and pace of the development processes of emerging technologies are associated with how they are perceived or expected by the public5,6,7,8,9,10,11, prior research has extensively scrutinized how the public perceives AVs. For example, Hilgarter and Granig1 qualitatively explored public perceptions of AVs across various dimensions, such as financial and technical concerns. Penmetsa, Sheinidashtegol2 analyzed the dynamics of tweets about AVs and related companies following car crash incidents.

Notwithstanding such a growing understanding of the public perception of AVs, prior research lies exclusively on end-users when referring to the ‘public.’ Particularly, it has predominantly focused on end-users’ perception of artificial intelligence (AI) within AVs. While AI is undoubtedly a key driver in transforming the conventional automotive industry through AVs, an exclusive focus on public perception of this sole technology yields an incomplete understanding of the technological transition occurring within the automotive sector.

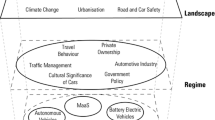

According to the sociotechnical regime framework12, transitions catalyzed by emerging technologies necessitate comprehension not only of the technologies themselves but also of the sociotechnical context—including industrial structure, value chain, regulatory and policy, and other related underlying component technologies. In this respect, there remains limited empirical evidence regarding public perception of AVs within this comprehensive technological and sociotechnical context. This limited perspective hinders our ability to fully understand the multifaceted factors contributing to the technological transition within the automotive sector through AVs.

This paper contributes to the literature by employing a state-of-the-art topic modeling technique to empirically explore the multifaceted public discourse on AVs within the sociotechnical regime framework. Specifically, we employ BERTopic to empirically explore the multifaceted public perception reflected in news media. Given that prior research has predominantly focused on public perception of AI, we further delve into public perceptions of battery technology, another pivotal component of AVs.

Battery technology is selected to redirect attention to a crucial AV component beyond AI, in light of the increasing public interest in its associated technological and sociotechnical challenges. First, despite its high expectations, battery technology in the automotive industry (particularly in the electric vehicle industry) continues to grapple with multifaceted challenges, such as autonomy, energy density, and charging systems13,14,15,16. For instance, AVs require substantial power to operate computer systems, sensors, and AI processing units, making efficient battery management systems (BMS) critical17,18. Moreover, Lee, Kang19 highlight that the performance of shared AVs heavily depends on battery degradation.

In addition to technological challenges, battery technology in vehicles also encounters significant non-technological issues. Safety concerns are paramount; lithium-ion batteries, which serve as the primary power source for most autonomous electric vehicles, pose risks such as overheating, thermal runaway, and fire hazards20. Furthermore, issues related to charging infrastructure development, raw material scarcity, and environmental sustainability constitute critical non-technological challenges21,22,23,24.

To empirically examine how AVs and their component technology are being publicly perceived and discussed, we explore the following research questions:

What technological and non-technological issues of AVs are being publicly perceived?

What technological and non-technological issues of battery technology for AVs are being publicly?

How can such public perception be empirically and comprehensively analyzed using state-of-the-art semantic-based topic modeling techniques? And how are they different from conventional approaches?

Following this Introduction, “Public perception of autonomous vehicles” section offers a brief review of the literature on public perception of autonomous vehicles. The methodological framework used in this research is then elaborated in “Data and methodology” section. “Results and Discussion” section present the results and their subsequent discussion, respectively. Then, “Conclusion” section shows theoretical and practical implications, followed by limitations of this paper and future research agenda.

Public perception of autonomous vehicles

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in the U.S., responsible for setting and enforcing Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards, defined AVs as “those in which at least some aspects of a safety–critical control function (e.g., steering, throttle, or braking) occur without direct driver input”25. NHTSA26 classified AVs into six levels according to the level of autonomy. Level 0 implies momentary driver assistance, having drivers fully responsible for driving their vehicles with assistance from the vehicles’ automated systems. Although drivers are still fully responsible for driving their vehicles at Level 2, the systems can engage in steering along with acceleration and braking. Level 3 involves conditional automation, where both drivers and the systems can engage in driving vehicles. Level 5 implies full automation, where systems are fully responsible for driving vehicles, while drivers do not have to be engaged in driving.

Given that more than 90% of car accidents are caused by driver error1,3, AVs are expected to avert such accidents dramatically. For example, Fagnant and Kockelman27 expected a 50% decrease in car crash and injury rates when the market penetration rate of AVs increases to 10%, while this reduction intensifies to 90% when the market penetration rate rises to 90%. Moreover, AVs are not merely defined by vehicles’ autonomous capabilities to replace people engaging in driving their vehicles, to increase roadway safety and reduce congestion. Rather, they hold great promise, with the potential for transforming the automotive industry as well as the transportation system. They are expected to provide new business models both for commercial and private use, such as driving robots for freight transportation, carsharing services, and peer-to-peer carsharing1,27,28,29.

Accordingly, there has been a growing interest in the public perceptions of AVs. Particularly, a substantial body of research has primarily focused on public perception (or trust) of AI within AVs. As the backbone of AV technology, AI enables automated systems to assume partial or complete control of vehicles. However, advances in AI alone do not guarantee market acceptance; rather, the widespread adoption of AVs hinges on public trust in the emerging technology. Thus, a growing consensus in the literature suggests that, despite significant technological progress, AVs may struggle to gain acceptance without established public trust in AI30. In this respect, recent research has highlighted how the public perceives non-technological aspects of AI—such as legal frameworks, transparency, and compliance—that drive its rate of diffusion and adoption31,32.

Following this research stream, how the public perceives AI within AVs has been demonstrated from diverse perspectives. For example, in the context of public perception of AI’s ability, Rödel, Stadler33 demonstrated how user acceptance (UA) and user experience (UX) vary according to the levels of autonomy. They showed that UA and UX are highest at the degree of autonomy that has been already employed in up-to-date cars; however, they significantly decrease as the level of autonomy increases. Similar results are demonstrated by recent research1,34,35,36,37, indicating that AVs are challenged by public concerns about AI’s ability, particularly regarding the high level of autonomy. Along this line of research, prior research has addressed how public perception (or trust) of AI is driven by factors such as accidents by AVs2,38 or AI-related stakeholders39.

Despite such growing understanding, as discussed in the previous section, we posit that a more diverse array of issues—technological and non-technological—are publicly perceived and discussed. We expect critical issues—such as policy initiatives, public infrastructure, and macro-economic issues—have received substantial attention in public discourse despite being comparatively underexamined in the literature. These elements represent fundamental prerequisites for the technological transition of the existing automotive industry paradigm12.

Data and methodology

Data

We posit that a limited range of public perceptions of AI within AVs arises from limitations in data sources, as prior research has predominantly relied on data from survey or social media platforms. Thus, we propose to utilize news articles to empirically and comprehensively explore the issues of AVs that are publicly perceived. News articles provide nuanced coverage across diverse domains. For example, Mulyani, Saifurrahman40 demonstrate that, compared to social media platforms, news articles encompass a substantially more comprehensive topical range, including governmental initiatives, public infrastructure development, and key stakeholder perspectives. Accordingly, news articles are a preferred data source in other strands of innovation literature, such as hype or public expectations8,9,41,42,43,44.

To construct the sample, we collected news articles published in the last 20 years (i.e., from 2002 to 2021) from ProQuest ABI/INFORM database45,46. The process of data collection was performed from October 11th to November 7th of 2022. We queried for news articles containing related keywords41,46. We selected AVs related news articles containing “autonomous vehicle*,” “autonomous car*," “autonomous driv*,” “self-driving,” or “driverless”. Then we selected battery technology-related sentences by selecting sentences that contain related words such as ‘batter*’. For the sake of feasible analysis, excluded those with less than 10 words. Subsequently, we excluded the news articles with duplicated titles, resulting in 11,708 news articles about AVs.

Methods

The document-level semantic analysis neglects the possibility of a document containing multiple topics, failing to identify more detailed topics47. To cope with the concern of the poor performance of semantic analysis at the article level, distinct from prior research, we perform semantic analysis at the paragraph level. Considering the coherence and relevance of information in a paragraph, semantic models often analyze at the paragraph level with the assumption that each paragraph represents one representative topic48,49,50,51. Accordingly, we assume that the main themes of the news articles selected for analysis are relevant to AVs and that these articles are further composed of multiple sub-themes, with each paragraph reflecting a specific sub-theme. Therefore, by breaking down articles into paragraphs48,52, we ensure that each unit of analysis aligns with the specific segmentation of information within the text.

To examine how battery technology-related sociotechnical issues are discussed within the sub-themes of AVs, we further conduct the semantic analysis, extracting and analyzing sentences explicitly mentioning battery technology-related discourse. This approach enables us to capture how battery-related issues are conceptualized and articulated within AVs discourse from multidimensional sociotechnical perspectives. By integrating paragraph-level analysis of AV discourse with a targeted sentence-level examination of battery technology, we ensure thematic coherence while achieving the detailed resolution needed to explore their interplay within public discourse.

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, we use BERTopic53 for the semantic analysis at the paragraph and sentence levels. The model is often used for semantic analysis at the paragraph level because of its prominence in extracting topic representations for the relatively short length of the corpus47,54. Conventional topic models, such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA)55 and Negative Matrix Factorization56, express a document with bag-of-words. When expressing documents with bag-of-words, it implies that models ignore the relationship between words, making it challenging to identify semantic information in paragraphs. In contrast, BERTopic creates document embeddings to identify the semantic information of a document57, allowing better extraction of topic representations from short texts. Moreover, because conventional models assume the corpus to comprise multiple topics, they are not appropriate for paragraph-level analysis. On the other hand, BERTopic assumes each corpus has a specific topic, allowing for categorizing the most representative topic to describe the corpus57.

In traditional topic models, it is imperative to preselect the number of topics beforehand. However, BERTopic stands apart in that it does not mandate a predefined number of topics, as topics can be extracted automatically58,59. To determine the optimal topic structure, we trained BERTopic models with various topic counts (ranging from 5 to 50) and hyperparameter (such as the number of neighboring sample points or the minimum size of a cluster). Subsequently, we evaluated each using the Cv coherence score. Based on this evaluation, we selected several candidate models and manually examined the coherence and relevance of each topic by reviewing representative keywords and paragraphs (or sentences). This combined quantitative–qualitative approach allowed us to identify the most interpretable and thematically rich topic configuration for further analysis.

Given that not all paragraphs in news articles denote discourse about autonomous vehicles, we excluded paragraphs entitled to topics irrelevant to our research interest or with uninterpretable topics from further analysis60. In the resulting topic assignments, some paragraphs (or sentences) were labeled as topic -1, a default category used by BERTopic when a paragraph does not fit well with any topic cluster. They typically contained content unrelated to autonomous vehicle technologies or battery technology—such as stock summaries, legal news, or contact information of news articles—and were excluded from the semantic analysis. While we did not conduct paragraph-level (or sentence-level) coherence scoring or intercoder reliability testing, the removal of these segments followed a transparent and reproducible procedure grounded in both model output and human inspection.

Results

Publication trend

Figure 2 shows the yearly trends in the number of news articles related to AVs and the subset of those articles discussing battery-related topics. From 2005 to 2011, the number of AV-related articles remained very low, with fewer than 10 articles published each year. Starting in 2013, the number of articles began to rise steadily, reaching a peak in 2018 with 141 articles, of which 88 included battery-related topics. However, after 2018, the number of articles gradually declined, with 138 AV-related articles published in 2021, 86 of which mentioned batteries. This indicates that in comparing the trends of AV-related news articles, battery-related articles followed a similar trend but with a relatively smaller growth rate.

Semantic analysis of AVs

Therefore, among 174 topics extracted automatically, we focus on 45 topics for subsequent semantic analysis. As shown in Table 1, we entitled the topics based on the keywords for each topic, with representative corpora of each topic based on the results of BERTopic. Then, we classified the topics based on the dimensions of the sociotechnical system for transportation proposed by Geels12, Geels61. The topics were classified into one of the five dimensions in the socio-technological systems of transportation and one dimension, reflecting the close interrelationship between transportation and other systems (or markets).

Automobile (artefact) encompasses primary technological issues related to AVs incorporating artificial intelligence and associated core technological challenges. ETC-related markets or industries includes topics closely connected with markets or industries adjacent to AVs. Markets and user practices contain prospects for various market domains derived from AVs. Production system and industry structures incorporates enterprises directly correlated with AVs, industrial structures, and investments. Regulation and Policies refers to government departments’ announcements (or initiatives) or regulations for AVs.

The dimension of the sociotechnical systems with the largest number of topics is Production system and industry structure, with 19 topics classified to the dimension. Production system and industry structure refers to issues of companies in the transportation industry, such as strategies or performance of the companies. Therefore, in this dimension, there are topics addressing issues about (a) incumbent automobile manufacturers, such as Ford or GM, (b) AVs-related tech companies, such as Google or Tesla, and (c) their activities or performance, such as firms’ activities in China or firms’ performance. An example of firms’ activities in China is:

There are a whole bunch of states and cities in the United States like Chicago that are willing to expand trade and economic cooperation with China. MOFCOM, together with 25 Chinese provinces and cities, has established trade and investmCent cooperation working groups with seven states and cities in the United States. Amity between the people holds the key to sound state-to-state relations…. (Asia News Monitor, July 25th, 2018)

Following Production system and industry structure, the next dimension with the largest number of topics is Auotomobile (artefact), with 11 topics. The dimension discusses the current state or expectations on AVs-related emerging technologies. It consists of topics such as artificial intelligence, autonomous levels, or sensors, network system. Examples of autonomous levels are:

All three of the company’s models are to be equipped with level 2-3 autonomous features, which include 30 smart features divided into seven groups: intelligent steering assist system, lane control system, active journey control system, multi-point collision warning system, comprehensive collision mitigation system, intelligent automated parking system and driver monitoring system (Asia News Monitor, February 9th, 2021)

There are also publicly discussed issues regarding legal or policy issues in the dimension of Regulation and policies. In Regulation and policies, there are two topics—national departments and agencies, safety issues, and sensors and safety issues—discussing legal or policy issues to facilitate or manage the development of AVs. The first topic is regarding announcements from national departments or agencies to foster or manage R&D activities on AVs. The last two topics are regarding safety issues, which is one of the primary concerns of AVs. Safety issues deals with more general safety issues. Examples of each topic are:

NSW plans to “embrace” automation of transport systems, state transport secretary Rodd Staples said as Japan’s Hitachi, which helped develop Rio Tinto’s new driverless Pilbara trains, said its technology could be transferred to passenger trains (The Australian Financial Review, July, 27th, 2018)

States are starting to introduce insurance rules for driverless cars. Earlier this year, California regulators proposed that manufacturers of autonomous vehicles would have to have $5 million in liability insurance to provide coverage. The Trov insurance policies would only cover people inside driverless cars (Wall Street Journal, December 20th, 2017)

Semantic analysis of battery technology for AVs

As aforementioned, we subsequently separated the paragraphs into the sentence level and employed BERTopic analysis at the sentence level. Among 16 topics extracted automatically, we selected 15 topics specifically related to battery technology and labeled them based on their keywords and the sentences that were grouped into. As shown in Table 2, when classifying these topics within the framework of sociotechnical systems, most battery-related topics are grouped into two categories: Production system and industry structure and Automobile (artefact). The former category encompasses topics related to firms’ activities, while the latter focuses on technological issues. The other prominent topic that emerged was related to Road infrastructure and traffic systems, highlighting the critical role of physical infrastructure—such as charging stations, road design, and traffic management systems—in facilitating the adoption of electric autonomous vehicles (EAVs). This suggests that beyond technological advancements in vehicles themselves, the readiness and adaptability of surrounding infrastructure are equally essential in shaping the public’s perception and acceptance of EAVs.

Table 3 presents what battery technology-related issues were publicly perceived and discussed within AVs-related issues. Within the Production system and industry structure, the most frequently discussed topics are Tesla, followed by Global lithium-ion battery industry and GM. For the Automobile (artefact), the top three topics are Alternative fuel technologies, Batteries vs hydrogen fuel cells, and Mileage.

With respect to those related to firms’ activities, the topics highlight the extent of interest in and efforts to advance capabilities in autonomous driving technology and battery technology. For instance, the following news articles are classified under Tesla in both AVs-related and battery technology-related contexts. These highlight Tesla’s performance and activities in self-driving and battery technology. The following examples illustrate how battery technology is discussed (in bold) within the AV-related paragraphs (in italics).

Tesla is considered by many as a visionary who is transforming the world with every move of his. His electric car company called Tesla has been redefining how people commute in a world where climate change is one of the biggest concerns, as the cars run on solar powered battery instead of fossil fuels. It also was the first company to launch self-driving car hardware. However, the cars still need much improvement in its software before they are made available to the public. (Financial Express, December 7th, 2016)Footnote 1

Similarly, the battery technology-related topic GM is linked with AVs-related topics such as firms’ performance, tesla, and electric_vehicles. Such interlinkage shows how GM has committed to strengthening its capabilities in electric and autonomous vehicles.

General Motors Co. will scale back operations in … while investing more in autonomous and electric vehicles. … The company is shrinking its global footprint in part to free up capital for bets on electric and autonomous vehicles and other advanced technologies. GM is the most aggressive traditional auto makers in pursuing battery-powered vehicles, … (Wall Street Journal, February 17th, 2020).

Other topics, such as artificial intelligence from AVs category, are aligned with battery-related topics such as Investments in battery technology, Battery packs or cells, or battery charges. They demonstrate the technological issues—such as BMS, battery packs, or chargers—of battery technology for AVs like below:

Distributed, autonomous recharging parks will make petrol stations redundant. Electric AVs can be stored in dense recharging parks, interspersed throughout a city. AV battery systems will be optimally sized for typical use, in contrast to the expensive, oversized batteries in private electric vehicles required to alleviate “range anxiety” of prospective buyers (The Australian Financial Review, February 6th, 2016).

The linkage of battery technology-related topics with the topics such as forecast of transportation system from AVs category demonstrate non-technological issues of battery technology—such as battery supply chain or charging infrastructure—that need to be resolved for the public to adopt AVs.

Innovate UK has up to £25 million to invest in new automotive battery technologies that help to build the vehicle battery supply chain in the UK Supporting the Industrial Strategy… This is a joint commitment to work together and invest in areas of UK strength, including connected and autonomous vehicles, battery technology and ultra-low and zero emission vehicles (Asia News Monitor, January 17th, 2018).

The battery-related topics such as Alternative fuel technologies including battery EV and Batteries versus hydrogen fuel cells are linked with AVs-related topics such as Forecast of transportation system, implying that there are other competing alternative technologies instead of battery technology:

The fact the future of motoring is electric seems almost without question. … They will be powered by electricity, whether drawn from batteries or from hydrogen fuel, and they will at long last remove mass transport from environmental debate, if not the debates of safety and congestion (Sunday Business Post, May 19th, 2017).

Discussion

AVs have have gained considerable prominence for their potential to transform existing transportation systems. However, negative public perceptions can hinder these disruptive innovations from realizing their expected economic and social impacts. Recent research has largely focused on public perceptions of AVs, yet most studies have primarily concentrated on end-user viewpoints.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to empirically investigate the diverse range of public perceptions surrounding AVs and the component technology, battery technology. We further demonstrate how state-of-the-art topic modeling techniques can be applied to uncover such perceptions empirically.

Regarding the first two research questions, our findings reveal that various issues—including both technological and non-technological issues—of AVs and their battery technology have been publicly perceived over the past two decades. We classified the perceived topics according to the sociotechnical regime framework. Accordingly, we identified a diverse range of 45 issues being publicly perceived, which were categorized into six sociotechnical dimensions. These include not only expected themes such as safety and technical performance but also emerging concerns about regulatory frameworks, labor displacement, and infrastructure readiness. This highlights the complex and evolving nature of AV-related public concerns, which go beyond technical functionality.

We further delved into how battery technology-related issues are publicly perceived within AVs. We extracted 15 recurring themes, which were categorized into three sociotechnical dimensions. The findings show that public perception around battery technologies is closely tied to broader debates about industrial competitiveness, supply chains, and the pace of infrastructure deployment.

With respect to the third question, our application of BERTopic demonstrates the value of semantic-based topic modeling in capturing a nuanced and comprehensive landscape of public perception of emerging technologies. Specifically, we analyzed news articles by employing the BERTopic model at the paragraph level to capture the multifaceted discourse surrounding AVs. We further analyzed at the sentence level to examine public perceptions of battery technology for AVs. This approach allows for scalable, interpretable, and thematically rich insights into large text corpora, making it a powerful tool for research at the intersection of technology and society.

Conclusion

Our findings make several important contributions. First, we broaden the scope of inquiry by exploring how public perceptions are constructed around critical technological components beyond autonomous capabilities. Whereas prior research has predominantly emphasized the vehicles’ self-driving functions, our study highlights the essential role of enabling technologies—such as battery technology, battery management systems (BMS), battery supply chains, and recharging infrastructure—in facilitating the practical commercialization of AVs. Moreover, our analysis reveals the presence of competing emerging technologies within this domain.

Second, by addressing non-technological challenges from a diverse perspective, we extend the literature on AV public perceptions. While earlier work has largely concentrated on safety concerns, our results indicate that issues such as regulatory frameworks, infrastructure development, and job displacement are also salient in public discourse.

Our findings offer several practical implications. First, by applying a state-of-the-art topic modeling technique (BERTopic) to a large corpus of news articles, we demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach in capturing and monitoring nuanced public perceptions of emerging technologies without narrowing the analytical scope. This method enables practitioners to identify early public concerns, track discourse shifts around key events, and adjust technological development and communication strategies accordingly.

Moreover, our results show that public perception goes beyond safety and performance, encompassing concerns such as battery supply chains, regulatory uncertainty, and infrastructure readiness. These insights suggest the need for an integrated approach to AV deployment—one that aligns technological advancement with policy design, infrastructure planning, and public engagement. In sum, these implications suggest that data-driven perception analysis, leveraging real-time public discourse and advanced semantic tools, can serve as a strategic asset for developing responsive and socially nuanced innovation policies.

Despite such contributions, this paper acknowledges certain limitations and suggests future avenues for future research. First, we used news articles as data sources to illustrate the public perception of AVs; however, we did not differentiate the news articles based on their framing. Framing allows one to select which aspects to highlight. For example, some news articles could focus on individuals’ perceptions or their daily lives, i.e., personal framing, while others could cover content calling for societal discussion, i.e., societal framing62,63. Therefore, it would be interesting for future research to classify news articles based on different types of framing and examine different perceptions between them.

Second, this study has limitations regarding its scope of analysis. We focus solely on battery technology among the various components of autonomous vehicles (AVs). While battery technologies are undeniably vital, AVs comprise a broader range of technological and non-technological elements, including sensors, cybersecurity, and trust in AI. Given this, future research should examine these other dimensions, particularly the non-technical factors like public trust in AI, which play a crucial role in AV acceptance and deployment. Second, the study considers publicly perceived issues within a specific timeframe, without addressing how public perception may evolve over time. For instance, there is a need for future research to analyze how public trust in AI has changed in response to specific events or milestones, as such insights could offer valuable implications for shaping public discourse and informing policy on AVs.

Third, this paper attempted to explore the public perceptions of AVs by employing the BERTopic model at the paragraph level. Although the approach provided a comprehensive understanding of the public perceptions of AVs, we also acknowledge the potential limitations of the BERTopic model itself. For example, although we thoroughly went to the preprocessing stages, such as selecting the optimal number of topics or removing irrelevant topics, the model may generate fragmented or overlapping topics, making interpretation challenging. Additionally, since topic labels are manually assigned, subjectivity may be introduced. Recent models, such as Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis64,65 or Large Language Model (LLM) models, can be employed in future research to identify how different innovation actors in sociotechnical systems perceive varying topics about AVs. We deem it would be more effective to implement such models when pre-trained word embeddings suited for texts of our interest are available.

Lastly, we used a simple query to select news articles. Particularly in the case of retrieving data from academic papers or patents, it is important to construct precise search queries66. However, due to the inherent nature of news articles, there are limitations in formulating such sophisticated queries. Nevertheless, prior studies have similarly adopted approaches that collect and filter news articles containing core keywords41,46, which suggests that this does not pose a significant methodological concern. Another limitation in data collection lies in the temporal scope of this study, as the dataset only includes articles up to the year 2021. Consequently, issues that emerged after 2022 could not be addressed in this paper. Despite these limitations, the significance of this study lies in proposing a methodology that utilizes the BERTopic model and news articles to capture and analyze public perception surrounding emerging technologies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

The paragraphs addressing AVs is formatted in italics, with a specific sentence regarding battery technology emphasized in bold.

References

Hilgarter, K. & Granig, P. Public perception of autonomous vehicles: A qualitative study based on interviews after riding an autonomous shuttle. Transport. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 72, 226–243 (2020).

Penmetsa, P. et al. Effects of the autonomous vehicle crashes on public perception of the technology. IATSS Res. 45(4), 485–492 (2021).

Rezwana, S., Shaon, M. R. R. & Lownes, N. Understanding the changes in public perception toward autonomous vehicles over time. In International Conference on Transportation and Development 2023 (2023).

Chan, C.-Y. Advancements, prospects, and impacts of automated driving systems. Int. J. Transport. Sci. Technol. 6(3), 208–216 (2017).

Borup, M. et al. The sociology of expectations in science and technology. Technol. Anal. Strategy. Manag. 18(3–4), 285–298 (2006).

Kaplan, S. & Tripsas, M. Thinking about technology: Applying a cognitive lens to technical change. Res. Policy 37(5), 790–805 (2008).

Ruef, A. & Markard, J. What happens after a hype? How changing expectations affected innovation activities in the case of stationary fuel cells. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 22(3), 317–338 (2010).

Alkemade, F. & Suurs, R. A. Patterns of expectations for emerging sustainable technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 79(3), 448–456 (2012).

Van Lente, H., Spitters, C. & Peine, A. Comparing technological hype cycles: Towards a theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80(8), 1615–1628 (2013).

Shi, Y. & Herniman, J. The role of expectation in innovation evolution: Exploring hype cycles. Technovation 7, 102459 (2022).

Zhang, W., Zhang, H. & Deng, Z. Public attitude and media governance of biometric information dissemination in the era of digital intelligence. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 2419 (2025).

Geels, F. W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 31(8–9), 1257–1274 (2002).

Ajao, Q. M. et al. An overview of lithium-ion battery dynamics for autonomous electric vehicles: A MATLAB simulation model. Open Access Lib. J. 10(6), 1–16 (2023).

Devanahalli Bokkassam, S. & NambiKrishnan, J. Lithium ion batteries: Characteristics, recycling and deep-sea mining. Battery Energy 3(6), 20240022 (2024).

Wulandari, T. et al. Lithium-based batteries, history, current status, challenges, and future perspectives. Battery Energy 2(6), 20230030 (2023).

Nguyen, D. M., Kishk, M. A. & Alouini, M.-S. Dynamic charging as a complementary approach in modern EV charging infrastructure. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5785 (2024).

Thilak, K. R., et al. An investigation on battery management system for autonomous electric vehicles. In 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT). (IEEE, 2023).

Badue, C. et al. Self-driving cars: A survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 165, 113816 (2021).

Lee, U., Kang, N. & Lee, Y. K. Shared autonomous electric vehicle system design and optimization under dynamic battery degradation considering varying load conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 423, 138795 (2023).

Kim, J., Kim, Z. & Lee, D. H. Prediction of the emergence of solid-state battery technology in the post-lithium ion battery era: A patent-based approach. Int. J. Green Energy 7, 1–16 (2023).

Newton, G. N. et al. Sustainability of Battery Technologies: Today and Tomorrow 6507–6509 (ACS Publications, 2021).

Esmaio, M. A. & Alsharif, A. The future of electric vehicles: innovations in battery technology and charging infrastructure. Open Eur. J. Eng. Sci. Res. 6, 44–55 (2025).

Weil, M., Peters, J. & Baumann, M. Stationary battery systems: Future challenges regarding resources, recycling, and sustainability. In The Material Basis of Energy Transitions 71-89. (Elsevier, 2020).

Zanoletti, A. et al. A review of lithium-ion battery recycling: Technologies, sustainability, and open issues. Batteries 10(1), 38 (2024).

NHTSA. Preliminary Statement of Policy Concerning Automated Vehicles 1–14. (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2013).

NHTSA. Automated Vehicles for Safety. 2023 [cited 2023 September 14, 2023]. Available from: https://www.nhtsa.gov/technology-innovation/automated-vehicles-safety

Fagnant, D. J. & Kockelman, K. Preparing a nation for autonomous vehicles: Opportunities, barriers and policy recommendations. Transport. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 77, 167–181 (2015).

Faisal, A. et al. Understanding autonomous vehicles. J. Transport Land Use 12(1), 45–72 (2019).

Maurer, M. et al. Autonomous Driving: Technical, Legal and Social Aspects (Springer, 2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Critical roles of explainability in shaping perception, trust, and acceptance of autonomous vehicles. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 100, 103568 (2024).

Afroogh, S. et al. Trust in AI: Progress, challenges, and future directions. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11(1), 1–30 (2024).

Ho, S. S. & Cheung, J. C. Trust in artificial intelligence, trust in engineers, and news media: Factors shaping public perceptions of autonomous drones through UTAUT2. Technol. Soc. 77, 102533 (2024).

Rödel, C., et al. Towards autonomous cars: The effect of autonomy levels on acceptance and user experience. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications (2014).

Hewitt, C., et al. Assessing public perception of self-driving cars: The autonomous vehicle acceptance model. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces (2019).

Aldakkhelallah, A. et al. Public perception of the introduction of autonomous vehicles. World Electric. Veh. J. 14(12), 345 (2023).

Luo, C., He, M. & Xing, C. Public acceptance of autonomous vehicles in China. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 40(2), 315–326 (2024).

Othman, K. A microscopic analysis of the relationship between prior knowledge about self-driving cars and the public acceptance: A survey in the US. Transport Telecommun. 24(2), 128–142 (2023).

Ward, C., et al. Acceptance of automated driving across generations: The role of risk and benefit perception, knowledge, and trust. In Human-Computer Interaction. User Interface Design, Development and Multimodality: 19th International Conference, HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 9–14, 2017, Proceedings, Part I 19. (Springer, 2017).

Goh, T. J. & Ho, S. S. Trustworthiness of policymakers, technology developers, and media organizations involved in introducing AI for autonomous vehicles: A public perspective. Sci. Commun. 46(5), 584–618 (2024).

Mulyani, Y. P. et al. Analyzing public discourse on photovoltaic (PV) adoption in Indonesia: A topic-based sentiment analysis of news articles and social media. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140233 (2024).

Mejia, C. & Kajikawa, Y. Technology news and their linkage to production of knowledge in robotics research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 143, 114–124 (2019).

Konrad, K. et al. Strategic responses to fuel cell hype and disappointment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 79(6), 1084–1098 (2012).

Aaldering, L. J. & Song, C. H. Tracing the technological development trajectory in post-lithium-ion battery technologies: A patent-based approach. J. Clean. Prod. 241, 118343 (2019).

Fenn, J. & Raskino, M. Mastering the Hype Cycle: How to Choose the Right Innovation at the Right Time (Harvard Business Press, 2008).

Johnson, P. C. et al. Digital innovation and the effects of artificial intelligence on firms’ research and development—Automation or augmentation, exploration or exploitation?. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 179, 121636 (2022).

Lehmann, J. et al. Institutional work battles in the sharing economy: Unveiling actors and discursive strategies in media discourse. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 184, 122002 (2022).

Egger, R. & Yu, J. A topic modeling comparison between LDA, NMF, Top2Vec, and BERTopic to demystify twitter posts. Front. Sociol. 7, 886498 (2022).

Vrana, S. R. et al. Latent semantic analysis: A new measure of patient-physician communication. Soc. Sci. Med. 198, 22–26 (2018).

Wiemer-Hastings, P., Wiemer-Hastings, K. & Graesser, A. Latent semantic analysis. In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2004).

Xianghua, F. et al. Multi-aspect sentiment analysis for Chinese online social reviews based on topic modeling and HowNet lexicon. Knowl.-Based Syst. 37, 186–195 (2013).

Silveira, R., et al. Topic modelling of legal documents via legal-bert. In Proceedings 1613, 0073. http: // ceur - wsorg (2021).

Shao, Y., et al. BERT-PLI: Modeling Paragraph-Level Interactions for Legal Case Retrieval. In IJCAI. (2020).

Grootendorst, M., BERTopic: Leveraging BERT and c-TF-IDF to create easily interpretable topics. Zenodo, Version v0, 9 (2020).

Salmi, S. et al. Detecting changes in help seeker conversations on a suicide prevention helpline during the COVID-19 pandemic: In-depth analysis using encoder representations from transformers. BMC Public Health 22(1), 1–10 (2022).

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y. & Jordan, M. I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 993–1022 (2003).

Févotte, C. & Idier, J. Algorithms for nonnegative matrix factorization with the β-divergence. Neural Comput. 23(9), 2421–2456 (2011).

Grootendorst, M., BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure (2022). arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.05794

Wang, Z. et al. Identifying interdisciplinary topics and their evolution based on BERTopic. Scientometrics 8, 1–26 (2023).

Jeon, E., Yoon, N. & Sohn, S. Y. Exploring new digital therapeutics technologies for psychiatric disorders using BERTopic and PatentSBERTa. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 186, 122130 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Identification of product innovation path incorporating the FOS and BERTopic model from the perspective of invalid patents. Appl. Sci. 13(13), 7987 (2023).

Geels, F. W. Processes and patterns in transitions and system innovations: Refining the co-evolutionary multi-level perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 72(6), 681–696 (2005).

Chuan, C.-H., Tsai, W.-H. S. & Cho, S. Y. Framing artificial intelligence in American newspapers. In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (2019).

Strekalova, Y. A. Informing dissemination research: A content analysis of US newspaper coverage of medical nanotechnology news. Sci. Commun. 37(2), 151–172 (2015).

Do, H. H. et al. Deep learning for aspect-based sentiment analysis: A comparative review. Expert Syst. Appl. 118, 272–299 (2019).

Hu, M. & Liu, B. Mining and summarizing customer reviews. In Proceedings of the tenth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (2004).

Wang, Z. et al. Updating a search strategy to track emerging nanotechnologies. J. Nanopart. Res. 21, 1–21 (2019).

Funding

Funder Name : Korea Institute of Energy Research (Grand ID : C5-2448).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Inje Kang—conceptualized the research models, analyzed data, and wrote the draft of the article. Jiseong Yang acquired, cleansed, and analyzed data. Zhunwoo Kim coordinated the research and proofread the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, I., Yang, J. & Kim, Z. Unveiling public perceptions of battery technology in autonomous vehicles via topic modeling of news articles. Sci Rep 15, 21884 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05318-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05318-0