Abstract

This paper introduces a metasurface absorber (MSA) sensor designed for fuel adulteration detection in the sub-terahertz (THz) range. The MSA features mirror-symmetric separated half-circle (MSSHC)-shaped resonators, a gold ground plane, and a dielectric layer, operating effectively within the 4.4–5.4 THz frequency range. It achieves notable absorption peaks at 4.94 THz. The resonance frequencies can be finely tuned by adjusting the geometric dimensions, ensuring optimal absorption. The MSA detects various additives in diesel, gasoline, and octane by monitoring shifts in resonance frequencies corresponding to changes in the oil’s refractive index (RI). The absorber demonstrates a Q-factor of 304.35, a figure of merit (FOM) of 7.15 RIU−1, and a maximum sensitivity of 120 GHz/RIU in diesel detection. This innovative concept holds significant potential as an efficient fuel oil sensor within the automotive industry. Its structural tunability, high sensitivity, and practical design render it a promising sensor for chemical detection and biosensing applications in the THz regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fuel is a pivotal energy source underpinning the global economy, with nations endowed with substantial oil reserves accruing significant economic advantages while those devoid of such resources incur considerable import expenses. However, the pernicious practice of fuel adulteration—augmenting commercial fuels with substances like kerosene or solvents to inflate volume for profit—raises grave concerns. This malpractice not only compromises fuel quality but also inflicts severe damage on engines and the environment. For instance, the admixture of kerosene into diesel can precipitate the formation of sulfuric acid during combustion, which can severely corrode engine components and fuel injection systems. To mitigate these risks, the implementation of stringent regulations is imperative to combat fuel adulteration, thereby safeguarding consumers, preserving equipment integrity, and protecting the environment1. Engines and other machinery may suffer damage if water is inadvertently or intentionally mixed with other materials. It leads to not only the reduction in energy efficiency which affects vehicle performance, but also leads to increased fuel consumption2. Adulterants can significantly increase the emissions of harmful pollutants from vehicles, worsening urban air quality and contributing to health problems among the population3. Quality regulations of fuels are crucial to prevent issues like machinery damage, low energy output, and environmental harm. It’s important to monitor the trace amounts of additives and other chemicals in fuels to make sure they’re not contaminated. However, detecting fuel adulteration is particularly challenging due to the complexity of petroleum-derived fuels and their numerous possible adulterants. While several detection methods have been proposed, such as ultrasonic radiation4,5, fiber optics6, and lab-on-chip devices7. However, Sensors such as Optical sensors8, Sound/Ultrasound sensors9, and Photo Detector sensors10 play a crucial role in detecting oil adulteration due to their ability to provide real-time and accurate analysis. An MSA (Metasurface absorber) sensor is capable of rapidly and easily identifying the disparity between pure and contaminated fuel11. Research indicates that several absorbers have been developed in the past few years for multiple applications. Among these, liquid sensing is one of the most prevalent fields12. As a result, an MSA offers the best options for dealing with these problems. MSA are artificially crafted electromagnetic (EM) composite materials structured from an array of sub-wavelength components. They have gained immense popularity owing to their distinctive attributes, including a negative refractive index13, absorption of electromagnetic waves14,15, cloaking capabilities16, miniaturization of structures17, development of super-lenses18, polarization conversion19, optical reflection20, intelligent device applications21,22,23, and analogue computing24 among others. Such properties of MSA cannot be found in natural materials. Having these foreign properties, researchers were greatly intrigued by investigating MSA and designing a variety of devices that included filters, modulators, sensors, and absorbers15,25. MSAs have garnered significant interest in research because of their remarkable capabilities and diverse range of applications26, particularly in the THz frequency range. Electromagnetic waves with frequencies from 0.1 to 10 terahertz, or between millimeter-wave and far-infrared, are referred to as THz waves27. The latest advances in THz technology have been made feasible by its enormous possibilities of use in imaging, spectroscopy, and sensing28,29. THz sensing and detection have been widely utilized to identify drugs, chemicals, and other compounds30,31,32,33. Through penetration of a wide spectrum of nonpolar materials, THz waves can determine the structural information of substances34,35. THz MSAs address many attractive advantages including rapidity, label-free detection, minimal ionization deterioration, and ease of use, and have shown promise in the field of tumor diagnosis36,37,38,39,40 and biomarkers41,42, liquid contamination detection43, fuel sensor44, food safety45, pesticide detection46, alcohol sensing47, and chemical detection48. Landy et al.49 presented the first-ever MSA, both theoretically and practically, with a narrowband absorption of 96%. The absorber may reach a narrow-band absorption of 96% at 11.48 GHz and 88% at 11.5 GHz through experimentation. The structure is composed of a severed wire for the ground plane, FR4 for the dielectric spacer, and a circular electric resonator for the upper patch. This near-perfect absorber has excellent features, such as ideal absorbance, a very thin dielectric, and a lightweight design. Particularly, such qualities motivated scientists to create implementations in the areas of sensing, thermal emitters, detection, and spectral imaging21. The MSA, however, was restricted to a single microwave frequency range and absorption band. Researchers are growing more interested in using THz to characterize metasurface-based systems. A metasurface-based microfluidic sensor, for instance, was proposed by Ebrahimi et al.50 utilizing an individual split-ring resonator (SRR) linked by a microstrip line, with the microfluidic channels positioned within the SRR’s void. However, this structure’s sensitivity is insufficient to differentiate between solutions with varying concentrations. Using linear regression analyses, density flooding principle, and a split-ring THz metasurface absorber reported by Chen et al.51 to identify trace pesticides with a 10 ng/L detection limit with good precision, including indole-3-acetic acid and tricyclazole. A multimode resonator with insensitive polarization and four individually adjustable functions in the range of 1 to 2 THz was reported by Veeraselvam et al.52, which is an insensitive polarization multi-mode resonator that has four individually adjustable functions over 1 to 2 THz. Ring dipole resonance was employed by Xu et al.53 to improve field confinement capabilities for ethanol solution investigation. Applications for biomedical and food safety employ THz biosensors based on MSAs extensively45,54. Mehmet et al.43 in 2018 first used MSA as a fuel sensor to distinguish branded and non-branded liquid fuels (gasoline, diesel). He employed FR4 as the substrate and copper as the surface metal. Khalil et al.55 2023 also designed an excellent MSA sensor to distinguish between clean and tainted oils as well as fuels, where copper and FR-4 were used as the resonator and dielectric layer, respectively. They worked with coconut oil and petrol in the GHz range and got a sensitivity of 5.65 GHz/RIU. A metasurface absorber was proposed by Zhisen Huang et al. which has an excellent absorption rate of over 99%, developed for sound absorption but has a very low Q-factor26. A terahertz metamaterial perfect absorber (MPA) was proposed by Bhati et al. for detecting microorganisms56. Although the absorber achieves an excellent absorption rate, the sensitivity is relatively low and could be further developed. Additionally, the paper lacks detailed information on the Q-factor and Figure of Merit (FoM), which are crucial for evaluating the sensor’s performance comprehensively. In57 a novel metasensor incorporating a square split ring resonator (SSRR) and a + type grooved resonator for sensing glucose and ethanol is designed in the lower terahertz frequency range. The sensor achieved a sensitivity of over 99%, but there is no mention of the Q-factor in the study. Though these sensors are accurate and provide great accuracy, they also have significant drawbacks. Sensitivity is a critical parameter in sensing, especially in the biosensing field. Some of these sensors are larger, some have complex and expensive constructions, and some have low sensitivity, Q-factor and FOM, etc. There are still issues that need to be addressed and develop a flexible balanced sensor to obtain compact, highly sensitive, flexible and which is convenient to fabricate as well.

This paper presents a robust novel MSA inspired by SRR design, operating in the THz range for the detection of fuel adulteration. The MSA shows sharp resonances. The MSA unit cell comprises a tri-layered structure with excellent features and facilitates easy fabrication using available materials. The resonator geometric shape is unique. And in terms of the results parameters including a sensitivity of 120 GHz/RIU for diesel analyte, an FOM of 7.15, and a Q factor of 304.35 outperform all other similar MSA in this field. The proposed MSA demonstrates exceptional capability in detecting key fuels such as octane and diesel. The proposed MSA demonstrates exceptional capability in detecting key fuels like octane and diesel. This device is relatively inexpensive, compact, and highly sensitive, making it ideal for lower THz microfluidic applications. The simulated result is highly consistent with the predicted one, indicating the sufficiency and precision of the simulated results and future scope with perspective application in other biosensing applications.

This paper presents a robust and novel metasurface absorber (MSA) inspired by the square split ring resonator (SRR) design, operating in the terahertz (THz) range for the detection of fuel adulteration. The MSA exhibits sharp resonances and comprises a tri-layered structure with excellent features, facilitating easy fabrication using readily available materials. The unique geometric shape of the resonator enhances its performance. The results demonstrate a sensitivity of 120 GHz/RIU for diesel analyte, a Figure of Merit (FOM) of 7.15, and a Q factor of 304.35, outperforming all other similar MSAs in this field. The proposed MSA shows exceptional capability in detecting key fuels such as octane and diesel. This device is relatively inexpensive, compact, and highly sensitive, making it ideal for lower THz microfluidic applications. The simulated results are highly consistent with the predicted outcomes, indicating the sufficiency and precision of the simulations. Furthermore, the device holds promise for future applications in biosensing, expanding its utility beyond fuel detection.

Methodology

Material selection

Material selection for metasurface absorber-based sensors is crucial for high performance and precision. Figures 1(a) and 1(b) show the proposed unit cell and its simulation setup. Noble metals like gold and silver enhance light-matter interactions at subwavelength scales, increasing absorption and scattering efficiency through strong plasmonic behaviour. Gold and silver are traditionally used for their ability to support localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs) and propagating surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) across various frequency ranges, including visible and infrared spectra58,59. They generally maintain lower losses compared to the other materials when optimized properly. Gold is highly resistant to oxidation and corrosion, making it suitable for long-term applications in harsh environments. This stability ensures that the optical properties of the metasurfaces remain consistent over time, which is particularly important in applications like sensors and imaging devices59. Such a novel metal Gold (Au) is chosen as the upper resonator layer and a thin ground plane. And a top-mounted patterned Gold, which is a very lossy metal in the optical region, has a thermal conductivity of 310 W/Km and electric conductivity of 4.5 × 107S/m60. The substrate layer, made of SiO2 with a 30 μm thickness, is positioned behind the resonator. SiO2 was chosen for its low cost, minimal loss, and mechanical strength. As a dielectric layer between metal layers, SiO2 excels in absorption due to its high melting point, low permittivity, and stable visible band properties. Its surface is nearly free of dangling bonds, thanks to a high density of fixed charge61. It has a low loss tangent of 0.001 and a relative permittivity of 3.962. The low-loss tangent property helps minimize energy dissipation, which is crucial for applications requiring high efficiency, such as sensors and absorbers operating in the infrared and terahertz ranges59,63.

Computational simulation constraint

The full-wave Finite Integration Technique (FIT) in Computer Simulation Technology (CST) 2021 version was utilized for sensor geometric optimization and calculation. It is based on a high-frequency electromagnetic analyzer. The computer used for the experiment has an AMD Ryzen 7 series (7730U) CPU and 16 GB RAM. The suggested metasurface unit cell is proposed with dimensions 100 × 100 × 30.77 µm3. An outline of the overall measurements of the suggested metasurface absorber is shown in Fig. 2. Using microwave analysis techniques, various boundary conditions were implemented, including Perfect Electrical and Magnetic Conductors (P.E.C and P.M.C.), free space, and pattern distribution to expedite the simulation processes and help with the suggested MM sensor’s dimensional structure optimization. To simulate the unit cell under TEM (Transverse electromagnetic) mode, PEC and PMC were employed in the y-z plane and x-y plane, respectively. The described boundary condition is based on the supposition that the conductors (PEC and PMC) under attention are perfect conductors with zero electrical resistance, which allows for the full reflection of electromagnetic waves. Conversely, the z-axis was identified as an open border. This indicates that the electromagnetic waves can go freely in that direction since there is no restriction or reflection in the z-direction.

Design evaluation

To get the ideal output, it is required to have an optimal structure, which was achieved by a trial-and-error method using the Computer Simulation Technology (C.S.T.) 2021 software. Figure 2(a-d) shows the step-by-step development of the resonator structure. The square-shaped tri-layer dimensions of the suggested metasurface unit cell are 100 × 100 × 30.77 µm3. The characteristics of the proposed metasurface are derived from the latest research on THz wavelength functions.

Four processes are involved in validating the suggested meta-surface unit cell geometry, depicted in the Figure 2. The ground metal layer and the dielectric insulator layer were developed in step 1 as two square shapes with spans of 100 μm, respectively, and heights of t3 = 0.3 μm and t2 = 30 μm. Next, the dielectric layer is covered with a metal half-circle; it is the resonator layer, as illustrated in Figure 2(a). In step 2, the same half circle was taken and placed oppositely in layer 1. Therefore, two half circles are placed at 37 μm, as seen in Fig. 2(b). In step 3, a rectangular shape is inserted between the two half-circles. It measures 74 μm in length and 6 μm in width. It is placed at the same distance from both sliced circles, as shown in Fig. 2(c). In the final step, two rectangular shapes are placed vertically at the end of each side of the rectangular shape, inserted in step 3. The length and width of the rectangular shape are 14 and 6, respectively. This constructs an H shape design in the center of layer 1, as seen in Fig. 2(d) or the whole resonating metallic section has a constant thickness that is t1 = 0.47 μm. Figure 2(e) illustrates the thickness of each layer from the side view.

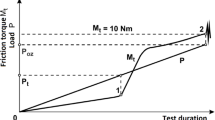

With a half-circle shape on the resonator layer, the initial design result is shown in Fig. 3, where the lowest point of reflection coefficient (S11) value is −37 dB at 4.912 THz. This design has multiple ripples at various frequencies, which makes it unsuitable for use as a sensing device. In design 2, when two sliced half-circle shapes are placed on the SiO2 layer, the S11 value at 4.846 THz is −21.08 dB. We proceed to additional modification because the reflection dip is so low here. The third design’s simulation results indicate an S11 value of −36.06 dB at 4.898 THz. Despite the larger reflection dip, three additional ripples in the 4.9–5.4 THz range were detected in the results. Therefore, we sought the ideal design that would have more depth and no ripples. In our finalized design, the S11 value of −46.4 dB at 4.925 THz and 40.8 dB at a frequency of 5.15 THz are seen in design simulation. With designs 1, 2, 3, and the final design as indicated in Fig. 2(d), respectively, where the resonating layer is put on the dielectric insulating layer, reflection progressively rises as the recommended unit cell is assessed.

In this investigation, the recommended unit cell layout is optimized using the trial-and-error technique to achieve optimum reflectance properties. Finalizing the proposed meta-structure unit cell involves tuning variables. Based on the latest studies concerning meta-structure absorbers in THz spectrum applications, the range of each parameter value is determined. Thus, the chosen parameter changed while assessing its absorption characteristics for different parameter sweeps, while all other geometric factors remained unchanged (Table 1). Figure 4(a-g) shows the reflection characteristics of the metasurface while varying different parameters. A parametric sweep analysis was done to observe the response of the metasurface due to the change of the values of the geometric entity. Initially, all the values were taken from recent research on THz metasurface area. Afterwards, the values were changed one by one. The investigation includes six geometric parameters: half circle radius (r), length of the vertical rectangle (z), width of the vertical rectangular shape (d), width of the horizontal rectangular shape (f), metal layer thickness (t1), substrate layer height (t2), and ground layer thickness (t3). While evaluating the parametric sweep, our focus was on a couple of perfect reflection dips within the 4.4 to 5.4 THz range because it would be perfect for the metasurface to function as an ideal sensor.

In the context of recent THz wavelength applications13,53,64 the resonator thickness of the metasurface is found to be between 0.2 and 0.7 μm. Hence, the reflectance properties were evaluated using a resonator thickness range of t1 = 0.30 to 0.55 at an interval of 0.05 μm. While increasing the thickness of the metallic layer, the simulation result shows a right shift of the reflection dip at the specific frequency of 5.0 to 5.2 THz (Fig. 4(e)). The depth of the reflection also rises while increasing layer thickness. We witnessed a significant dip for 0.55 μm because of this. Despite having an enormous dip, we chose rather than to take the 0.55 μm as there were some frequency ripples. However, the balanced and perfect dips were seen in 0.45–0.50 μm. So, 0.47 was taken as the thickness of the resonator layer. The values r, z, d, and f were adjusted through trial, they were simulated in different ranges to get the perfect output of the device, which is shown in the Figure. 4(a), 4(b), 4(c), and 4(d). According to current THz MM absorber studies43,51,65,66 regarding optical usage, the insulator height falls between 15 and 60 μm. Employing an insulating layer range of t2 = 20 to 40 μm at intervals of 5 μm, the absorption characteristics were assessed. For t2 = between 20 and 40 μm, the absorbent characteristics are displayed in the Figure. 4(f) when the dielectric insulator thickness is changed by 5 μm. For both 20 and 40 μm insulating layers, there is no significant reflection dip witnessed. However, if the layer thickness is 25–35 μm, then we found a reflection dip with several ripples present. But for a 30 μm dielectric layer, there is no ripple, but a couple of large reflection dips. So, the perfect reflection dip is produced by the design with a layer of dielectric insulator with t2 = 30 μm.

In the following inquiry, the ground layer thickness (t3) occupied for operation around the range of t3 = 0.2 to 0.4 μm at intervals of 0.05 μm was used to analyze the reflectance qualities (Fig. 4(g)). The reflection dip is not significantly impacted by changes in the thickness of the base layer. We detected a slight shift in the frequency to the right as we raised the layer’s thickness.

Possible fabrication of the proposed metasurface

It is feasible to create tiny nanoparticles with great dimensional precision because of the manufacturing processes67,68. Gentle nano-imprinting lithography and thermal evaporation technologies have been extensively utilized in the creation of nm and µm-sized metamaterial absorbers. The current manufacturing procedure, as shown in Fig. 5, can be used to fabricate the suggested meta-structure utilizing both thermal evaporation and lithography technologies. The first step is the preparation of a clear silicon substrate, which is the initial step in the fabrication of the proposed metamaterial unit cell. To enhance adhesion, guarantee a uniform surface, and mitigate mechanical stress, a sacrificial polyacrylic acid (PAA) layer is initially spin-coated onto the substrate63. The next step will involve the deposition of the insulator layer of the proposed meta-structure, the silicon and polyacrylic acid (PAA) films. The insulating layer can be positioned by the polystyrene (PS) resonating pattern. Next, the topmost resonator patterns will be inserted into the PS film at a depth equal to the resonating layer’s height. In the third phase, the embedded resonator structure is eliminated by submerging the sample in 5-weight% HF solutions. Following this, the sample will be submerged in distilled water to eliminate the PAA coating. Turning to the latter phase, magnetron sputtering will be used to break down the insulator layer and the ground layer made of gold within the identical vacuum tube. Finally, comparable magnetron sputtering helps to deposit a gold resonator layer.

Results analysis and discussion

The proposed metasurface unit cell’s absorption characteristics

The purpose of this study was to investigate the sensor’s capacity for identifying various oil sample kinds. The suggested structure’s spectrum response is assessed using regular incident electromagnetic waves that range in frequency from 4.4 to 5.4 THz. The EM behavior of metamaterials is characterized by the scattering parameters (S-parameters) which are derived using the Nicolson–Ross–Weir (NRW) method69. By analyzing the magnitude of the S-parameters as reflection coefficient, R(ω) = |S11(ω)| and transmission coefficient T(ω)= |S21(ω), absorption A(ω) can be found using Eq. 170.

It is necessary to reduce the reflection and transmission rates to almost nil to maximize metamaterial absorption71. It is implied that the intensity of the associated MA’s absorption peak can be dynamically modified from 1 to 100% since there is an ideal thickness of the dielectric layer (t2) for the current shape that maximizes absorbance. Furthermore, the reverse side has a gold surface with resistivity ρ = 2.44 and permeability µrµ0 = 0.7. The electromagnetic wave’s skin depth is computed using \(\:\delta\:=\sqrt{2\rho\:/{2\pi\:f\mu\:}_{r}{\mu\:}_{0}}\) = 0.5 μm, where the 0.3-µm-thick gold layer is insufficient to prevent the EM wave from being transmitted72. Thus, we also need to calculate the modest amount of transmittance that was present here. Here, we may express the predicted meta-structure’s reflectivity R(ω) as Eq. 2 for the transverse electric (TE) mode.

Where, ryy and rxy are co-polarised and cross-polarised component for TE polarized wave. Perfect absorption of EM waves can be accomplished if the effective impedance and the impedance at free space coincide, according to impedance matching theory73. The impedance of free space is \(\:{Z}_{0}=\sqrt{{\mu\:}_{0}}{/\epsilon\:}_{0}\) and Effective impedance is represented as, \(\:{Z}_{E}=\sqrt{{{\mu\:}_{0}\mu\:}_{r}\left(\omega\:\right)/{{\epsilon\:}_{0}\epsilon\:}_{r}\left(\omega\:\right)}\), where ε0 is the free space’s permittivity, εr is the medium’s permittivity, µ0 represents the free space’s permeability, and µr is the medium’s permeability. Permittivity and permeability are determined by frequency and material parameters74. By controlling the size and shape of the proposed structure, it is necessary to match the free space impedance with the MM unit cell impedance to achieve near unity absorbance. The angles θi, θr and θt correspond to the incident, reflected, and refracted rays at the interface. Snell’s law describes the relationship between these angles given in Eq. 3.

Both TE and TM modes affect the calculation of the R(ω) reflection coefficient, according to the Fresnel reflection Eqs37,75. Only TE mode is shown here in Eq. (4)

This equation demonstrates that the reflection coefficient is influenced by the impedance and the angles of incidence and transmission. Where:

-

Z1 and Z2 are the impedances of the two media.

-

θi is the angle of incidence.

-

θtis the angle of transmission.

We assume that the media are non-magnetic. Then the wave impedances are determined solely by the refractive indices n1 and n2 and can be written as, \(\:{Z}_{i}=\frac{{Z}_{0}}{{n}_{i}}\), where Z0 is the free space impedance and i ranges from 1 to 2. After this replacement, the refractive indices are used to produce the following equations (Eq. 5 to Eq. 7).

Where n1 and n2 are the refractive indices of the two media. In this case, θ and n stand for the wave incidence angle on the meta-structure unit cell structure and the refractive index of the suggested meta-structure unit cell structure, respectively. For normal incident waves, it is commonly believed that the wave incidence angle is zero. As a result, the reflection coefficient formula is changed to \(\:z={Z}_{E}/{Z}_{0}=\sqrt{\frac{{\mu\:}_{r}}{{\epsilon\:}_{r}}}\) in terms of normalized impedance, and reflection R may now be calculated using Eq. (6).

And the transmission T can be calculated using Eq. (7)

Where ZE is the wave impedance of the medium, Z0 is the free space impedance, z is the normalized impedance, µr is the relative permeability, ϵr is the relative permittivity.

So, the absorption equation can be written as

At the point when ZE equals free space impedance, absorbance becomes unity. A normalized impedance value of unity is derived from perfect match impedance.

By applying Snell’s law and trigonometric identity to eliminate θt, the second version of each equation may be obtained from the first. In this case, η and θ stand for the refractive index and the wave incidence angle on the proposed structure, respectively. For normal incident waves, it is commonly believed that the wave incidence angle α is zero. Therefore, the reflection coefficient formula is changed to \(\:z={Z}_{E}/{Z}_{0}=\sqrt{{\mu\:}_{r}/{\epsilon\:}_{r}}\), in terms of normalized impedance and reflection \(\:R\left(\omega\:\right)\:\)may now be calculated using Eq. 7. At the point when ZE equals free space impedance, absorbance becomes unity.

Figure 6(a) shows the absorption characteristics of our suggested metasurface for the frequency range of 4.4 to 5.4 THz. An outstanding absorption result has been shown for three distinct frequency points. The absorption is approximately 92.33% at 4.58 THz. It exhibited a roughly 95.2% absorption in the 4.92–4.98 THz band. Additionally, it displayed 95.2% absorption in the 5.13–5.18 THz band. The normalized impedance of the metasurface with both real and imaginary sections is displayed in Fig. 6(b). This graph is capable of being utilized to realize impedance matching. The real component of the impedance tends towards unity at frequency 4.58 THz, 4.92 to 4.98 THz and 5.13–5.18 THz, while the imaginary component is exactly zero at those same resonant frequency points. This finding verifies that the frequency point at which the three distinct absorption peak were achieved for the proposed design, the impedance of the meta-structure and free space is identical, thereby proving that the metasurface absorber exhibits a remarkable impedance match, indicating a perfect solution.

The interference principle could be performed to assess the absorption property. This method offers a more comprehensive understanding of how the absorber interacts with incoming EM waves by analysing the constructive and destructive pattern of interference within the metamaterial structure. The meta structure unit cell with a Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) sandwich architecture has a coupling method provided by an antiparallel passage of current between the base metallic layers and resonating layer (layers 1–3). Because of the opposing current flow inside the ground metal (third) layer and the resonator (first) layer, the configuration described produces both electric and magnetic resonance. Consequently, EM wave absorption is improved because of these resonance effects. During the initial interaction, the incoming electromagnetic wave hits the proposed MM unit cell. The wave is slightly reflected by the resonator layer (Level 1) which is given by the reflection, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{r}}_{11}\left(\omega\:\right)=\:{r}_{11}\left(\omega\:\right){e}^{{i\varPhi\:}_{11}\left(\omega\:\right)}\) and partially transmitted through the substrate sheet (Level 2) given by transmission coefficient \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{t}}_{21}\left(\omega\:\right)=\:{t}_{21}\left(\omega\:\right){e}^{{i\theta\:}_{21}\left(\omega\:\right)}\)t. The transmitted electromagnetic waves that finally reach the dielectric layer is again reflected by the ground plan having reflection coefficient = −1 and reaches level 1. But as the wave incident upon the resonator after travelling through the substrate it again reflected back to the dielectric medium which is given by, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{r}}_{22}\left(\omega\:\right)=\:{r}_{11}\left(\omega\:\right){e}^{{i\varPhi\:}_{11}\left(\omega\:\right)}\), and another component is transmitted through level-1 to air and is represented as \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{t}}_{12}\left(\omega\:\right)=\:{t}_{12}\left(\omega\:\right){e}^{{i\theta\:}_{12}\left(\omega\:\right)}\). This phenomenon is repeated and again resulting in multiple reflection at both resonator and ground layer and transmission through the substrate. Now the overall reflection wave of the first layer according to the interference theory is given by Eq. 969.

Within the substrate sheet, the electromagnetic wave’s propagation constant, \(\:\beta\:={\beta\:}_{1}+i{\beta\:}_{2}=\sqrt{{{\epsilon\:}_{\:}}_{d}}{k}_{o}d\), is made up of two components: β1, which is real, and β2, which is imaginary, εd and d are the permittivity and depth of the substrate, correspondingly and k0= wave number. But Transmission coefficient, S12=S21, so the final equation becomes Eq. (10).

Now the absorption coefficient can be determined using Eq. 1, which now becomes \(\:A\left(\omega\:\right){=1-\sum\:r}_{11}\), depends solely on the overall reflection coefficient \(\:{\sum\:r}_{11}\), as the transmission coefficient is nil due to the utilization of metal ground plane.

Meta material properties of the suggested framework

The amount of polarization that a material can undergo in reaction to an electric field, influencing the propagation of electromagnetic waves through it, is known as its permittivity. It is possible to engineer the permittivity, εr to have negative values in metamaterials, which is not commonly observed in natural materials. A material’s ability to enable the creation of magnetic fields within it is determined by its relative permeability, µr, which gauges the material’s response to a magnetic field. In metamaterials, µr can also be engineered to be negative, like εr. The relative permittivity and permeability of the structure can be known from the following Eqs. (11) and (12).

Here, d is the propagation distance, \(\:{k}_{0}=Wave\:Number=\frac{2\pi\:f}{c}\), \(\:C=velocity\:of\:light\), \(\:{A}_{1}=\sqrt{{r}_{yy}+{r}_{xy}}\) and \(\:{A}_{2}=\sqrt{{r}_{xy}-{r}_{yy}}\). The values of \(\:{r}_{xy},{r}_{yy}\) are obtained from CST MWS 2021 and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{r}\) are calculated with the help of MATLAB software. As shown in Figure. 6(a) and (b), the negative values of permittivity and permeability in the 4.4–4.48 THz and 4.0–4.3 THz frequency ranges, respectively, imply that the metamaterial displays double negative refractive index. It’s an inherent characteristic of metamaterials that could potentially find application in super lenses and cloaking, among other things. An essential characteristic that characterizes how light refracts, or bends, as it travels through a substance is the effective refractive index. Which is computed using relative permittivity and permeability. The resistance of a material to the passage of electromagnetic radiation is represented by its impedance. For free space, it’s approximately 377 ohms, but in metamaterials, it can be tailored to different values. Some terahertz (THz) frequency ranges include negative real components for both εr and µr. This negative number signifies a left-handed material in which the wave propagation direction is opposed to the direction of the energy flow (Poynting vector). This characteristic makes special phenomena possible, such as negative refraction. The geometric structure has a significant impact on the transmission and reflection coefficients. The quantity of the EM wave encountered that is reflected or transmitted through the metamaterial is determined by these coefficients. These coefficients can be changed thanks to the shape of the unit cell, which in turn regulates the metamaterial’s permeability and effective permittivity. Usually, the refractive index determined using Eq. (13), which determine the metamaterial characteristics of the proposed structure.

.

Figure 7 visually represents the variations in permittivity and permeability with frequency. We observed a sharp negative peak in permittivity between 4.4 and 4.75 THz and 4.92 to 5.05 THz, coinciding with shifts in the real and imaginary components of the metasurface. Similarly, permeability exhibited negative values in the ranges of 4.76 to 4.94 THz and 5.05 to 5.2 THz. These negative values enable complete electromagnetic wave energy absorption. Therefore, it shows that the refractive index of the proposed meta-structure unit cell is negative, as the permittivity and permeability are negative, which confirms the metamaterial characteristics. The behavior observed at the resonant frequency supports the classification of the suggested metasurface as a metamaterial.

Electric and magnetic distribution of the proposed

Scattering fields are produced by current flowing through the metallic part of the MM surface. The current passing through MM’s conducting element produces the magnetic field, and the electromotive force is created by variations in the magnetic field. The integral form of Maxwell’s formulas (Eqs. 14 and 15) can be used to calculate the absorber E and H fields for the operational wavelength76,77.

Here, E denotes the electric field density, B the magnetic flux density, H the magnetic field density, and D the density of electric flux for the unit cell surface. The E field distribution for the resonant frequencies 4.94 THz is depicted in Fig. 8. Each figure contains the distribution under both TE and TM modes at the same resonant frequency point. The wave is reflected off the ground as a surface plasmon when it strikes the surface of the absorber. As a result, interference on a dielectric surface causes multiple surface plasmon resonances (SPR), causing near-perfect absorption. According to absorption theory, the basic mechanism of MA is mainly dependent on the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), the propagating surface plasmon (PSPR) resonance78,79. The PSPR mode is a non-localized mode induced by mobile plasmons in an excited absorber. On the other hand, the LSPR mode is a localized mode generated within the dielectric insulator layer owing to the interference of the resonator and ground layer surface plasmons. Starting with E-field distribution at 4.94 THz, the field is denser around both the half circular-shaped resonator and around the central rectangular shape, which indicates the presence of LSPR. But as the frequency increases, the E-field becomes stronger than that of 4.94 THz but maintains the same pattern. An increase in field intensity upon the substrate surface and in the cavity of the resonator structures indicates the existence of cavity surface plasmon resonance (CSPR). Moving to the next frequency point, we observe the field is only concentrated around those two small rectangular shapes, which are due to LSPR. The H-Field distribution for the same frequency points as that of the E-Field distribution is illustrated in Fig. 8(b). The magnetic field was found to be more dominant than the E-field at 4.94 THz, as depicted in the Figure. 8(b). Being concentrated around the resonator structures, the field was also observed to be at the edge of the substrate, which explains that the surface plasmon resonance propagates through the substrate, indicating PSPR (Propagating surface plasmon resonance). But at TM mode, though the pattern is similar, the distribution is found to be less condensed. At 5.03 THz, the resonator patch has a dispersed H-field with greater intensity at the edges. Finally, at 5.15 THz, an increase in LSPR and PSPR, the upper surface of the unit cell, including both resonator and the substrate, is observed to be completely covered in the magnetic field.

Sensing precision

Q-factor (Q), figure of merit (FOM), and refractive index sensitivity (S) are frequently crucial metrics for assessing a THz MM sensor’s sensing efficacy80,81. The Q factor in metamaterial absorbers is a critical parameter that quantifies the efficiency and performance of these devices in resonating at specific frequencies. The proportion of the resonant frequency (f) to the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the resonance peak is known as the Q-factor82, given by Eq.

A higher Q factor indicates a narrower bandwidth and sharper resonance, allowing for better detection of changes in refractive index, which is desirable for applications requiring high sensitivity and selectivity83,84. The refractive index sensitivity (S), or the relation between the change in refractive index (Δn) and the resonant frequency shift (∆f) brought about by the presence of analytes, can be calculated using Eq85.

The FOM value, which can be presented as indicated in Eq. (19), is typically utilized to assess sensing performance under various resonant frequency zones.

Transmission efficiency (T) is a critical metric in power transmission, defined as the ratio of transmitted power (Tout) to input power (Tin). For metasurface absorbers, this efficiency determines whether power is transmitted, absorbed, or reflected86. The basic equation is:

Recent studies emphasize the importance of optimizing impedance matching and structural design to enhance absorption rates and transmission efficiency in metasurface absorbers.

Diesel

To detect diesel using this terahertz sensor, the analytes must be applied to the surface of the metamaterial. This ensures accurate substance identification. This will alter the ambient permittivity and shift the MM THz reflection spectrum’s resonance frequency. The refractive index (RI) of the additional substance may be ascertained by measuring the offset of the resonant peak; materials with varying refractive indices can be distinguished using this information. It is necessary to investigate the THz MM sensor’s sensing capabilities to increase its refractive index sensitivity and make a useful application of it. A diesel sample layer with a predetermined thickness of t = 2 μm was placed on top of the THz MM sensor. The related reflection spectrum of the suggested MMA is shown in Fig. 9, where a particular resonant peak at f = 4.846 THz is seen. The terahertz reflection spectra produced at the resonant frequency f by adjusting the analyte layer’s refractive index (n) from 1.23 to 1.63 with an increment of 0.1 are displayed in Fig. 9(a). As the amount of n grew, the resonant frequencies showed a range of redshift, and the value of frequency shift was used to identify the analytes to be examined with distinct refractive indices. The greater the value of n, the more the resonance peaks’ positions moved about linearly. In Fig. 9(b), the fitting curves’ slopes indicate the sensor’s refractive index sensitivity, which was S = 0.12 THz/RIU. The suggested THz MM sensor demonstrated greater refractive index sensitivity in comparison to the findings reported in previous works, making it possible to differentiate between analytes with comparable refractive indices87,88.

Octane

The matching reflection spectrum for the THz MM sensor is shown in Fig. 10(a), which also tests the sensor for octane. The frequency at which the resonant peak is reached is f = 4.848 THz. The analyte layer thickness for octane is the same (t = 2). The RI range in this experiment is 1.30 to 1.50, and the step is 0.05. Various degrees of frequency red shift are observed. Figure 10(b) shows the sensitivity from fitting curves’ slopes for octane, which is 110 GHz/RIU. The FOM value is 6.887.

The THz metasurface sensor was tested simultaneously for diesel and octane. For diesel, the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the peak is 0.016 THz, as shown in Fig. 9(a). Using Eq. (16), a Q-factor of 304.35 was calculated. The Figure of Merit (FOM), determined using Eq. (18), is 7.15, and the sensitivity for diesel is 0.12, as depicted in the fitting curve.

The sensitivity, as indicated by the slope of the fitting curves, is 0.11. For octane, the FWHM of the peak is 0.01597 THz, as illustrated in Fig. 10(a), with a Q-factor of 303.53. The sensitivity for octane, as indicated in Fig. 10(b) by the slope of the fitting curves, is 0.11. Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of Sensitivity, Q factor, and FOM for Diesel and Octane.

Analyzing and discussing comparative performance with current works

Sensor research prioritizes accurate, cost-effective metasurface absorbers (MSA) for diverse liquid detection. The novel tri-layer meta-structure offers a perfect absorption response and simple fabrication, marking a significant advancement in sensor technology. It demonstrates an exceptional reflectance response in the terahertz range, setting a new standard for sensor performance. Table 3 below shows the comparison of this work with some recent works in this field.

The comparative study presented in Table 3 highlights the significant contributions of the MSSHC absorber in relation to similar research. For instance, the MMA with a pixel shape resonator reported in89 has a sensitivity of 69.6 GHz/RIU, whereas our MSA demonstrates higher sensitivity. Additionally, while the Pythagorean tree fractal resonators in90 exhibit greater sensitivity than our work, their Q factors and Figure of Merit (FOM) are lower. The resonator in54 used for oil sensing has very low sensitivity compared to our MSSHC absorber. Although the absorbers in40 and 92 have higher sensitivity, their other parameters are significantly lower, causing them to lag behind our work. Furthermore, the resonators in93 to96 show lower or similar results, but our MSSHC absorber surpasses them easily in terms of overall performance97. presents a remarkable absorber for diagnosing blood cancer with excellent sensitivity. However, it has a lower Q factor compared to this work. Additionally, the working frequency range of 0–3000 THz poses significant challenges for the measurement setup. This comparison underscores the superior capabilities of the MSSHC absorber in various sensing applications.

Conclusion

This paper presents an advanced metasurface absorber MSA-based THz sensor is demonstrated with exceptional efficacy in detecting fuel adulteration. The sensor, centered around an MSSHC resonator, exhibits high specificity in absorbing electromagnetic waves within a targeted frequency range. Fabricated using a precise nanofabrication process, the sensor achieves a sensitivity of 120 GHz/RIU, a Q factor of 304.35, and a FOM of 7.15, ensuring the detection of even minor fuel adulterations. Comprehensive analysis of the absorptance mechanism, including the distribution of electric and magnetic fields and the electric surface current density on the meta-atom, validates the sensor’s potential for practical applications in detecting contaminants in fuels and oils. The sensor’s outstanding performance in sensitivity and specificity underscores its suitability for real-world automotive fuel quality monitoring and extends its applicability to chemical and biological material detection. Future research will focus on developing advanced data processing methods and multi-purpose sensor designs, with the potential to revolutionize liquid quality monitoring across various industries.

Data availability

Data will be provided upon inquiry. Contact: Sazzad Ahmed, Email: p147123@siswa.ukm.edu.my.

References

Rahad, R. et al. Fuel classification and adulteration detection using a highly sensitive plasmonic sensor. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 40, 100560 (2023).

Kakaei, A., Mostafaei, M. & Naderloo, L. Identification and classification of adulteration in some fossil fuel products using an electronic nose. Fuel 396, 135405 (2025).

Prashar, S., Tiwari, U. K. & Singh, S. Fuel adulteration detection sensor using sensitivity-optimized etched long-period fiber grating. J. Opt. 53 (5), 4532–4546 (2024).

Kumar, A. & Periyannan, S. Ultrasonic helical sensor for monitoring fuel adulteration and concentration. Sigma 43 (2), 533–540 (2025).

Bharath, L. & Himanth, D. A comprehensive review of ultrasonics application in detection of fuel adulteration. Int. J. Innovative Sci. Res. Technol., 2(10). (2017).

Joel, G. & Okoro, L. N. Spectroscopic and chromatographic methods for detection of adulteration in liquid petroleum and biomass fuels: a review. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 9, 1–5 (2020).

Harkare, A. H. Analytical Study for Development of Fuel Adulteration Detection System (Helix, 2018).

Chuma, E. L. & Rasmussen, T. Metamaterial-based sensor integrating microwave dielectric and near-infrared spectroscopy techniques for substance evaluation. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (20), 19308–19314 (2022).

George, T., Rufus, E. & Alex, Z. C. Artificial neural network based ultrasonic sensor system for detection of adulteration in edible oil. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 12 (6), 1568–1579 (2017).

Felix, V. J., Udaykiran, P. A. & Ganesan, K. Fuel adulteration detection system. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 8 (S2), 90–95 (2015).

Rawat, V., Nadkarni, V. & Kale, S. Highly sensitive electrical metamaterial sensor for fuel adulteration detection. Def. Sci. J. 66 (4), 421–424 (2016).

Abdulkarim, Y. I. et al. Design and study of a metamaterial based sensor for the application of liquid chemicals detection. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9 (5), 10291–10304 (2020).

Zakir, S. et al. Polarization-insensitive, broadband, and tunable Terahertz absorber using slotted-square graphene meta-rings. IEEE Photonics J. 15 (1), 1–8 (2022).

Cen, C. et al. Numerical investigation of a tunable metamaterial perfect absorber consisting of two-intersecting graphene Nanoring arrays. Phys. Lett. A. 383 (24), 3030–3035 (2019).

Landy, N. I. et al. Perfect metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 (20), 207402 (2008).

Li, J. & Pendry, J. B. Hiding under the carpet: a new strategy for cloaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101 (20), 203901 (2008).

Nickpay, M. R., Danaie, M. & Shahzadi, A. Graphene-based tunable quad-band fan-shaped split-ring metamaterial absorber and refractive index sensor for THz spectrum. Micro Nanostruct. 173, 207473 (2023).

Dhama, R. et al. Super-resolution imaging by dielectric superlenses: TiO2 metamaterial superlens versus BaTiO3 superlens. In Photonics (MDPI, 2021).

Anik, M. H. K. et al. Numerical investigation of a gear-shaped triple-band perfect Terahertz metamaterial absorber as biochemical sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (18), 17819–17829 (2022).

Ramaccia, D., Toscano, A. & Bilotti, F. Light propagation through metamaterial Temporal slabs: reflection, refraction, and special cases. Opt. Lett. 45 (20), 5836–5839 (2020).

Mehmood, M. Q. et al. Single-Cell‐Driven Tri‐Channel encryption Meta‐Displays. Adv. Sci. 9 (35), 2203962 (2022).

Zhu, R. et al. Remotely mind-controlled metasurface via brainwaves. ELight 2 (1), 10 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Spin-orbit-locked hyperbolic polariton vortices carrying reconfigurable topological charges. Elight 2 (1), 12 (2022).

Zangeneh-Nejad, F. et al. Analogue computing with metamaterials. Nat. Reviews Mater. 6 (3), 207–225 (2021).

Yan, Y. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic performance and mechanism of au@ CaTiO3 composites with Au nanoparticles assembled on CaTiO3 nanocuboids. Micromachines 10 (4), 254 (2019).

Zhao, C. et al. Structures, principles, and properties of metamaterial perfect absorbers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25 (44), 30145–30171 (2023).

Sizov, F. F. Brief history of THz and IR technologies. Semiconductor physics, quantum electronics & optoelectronics, 2019(22,№ 1): pp. 67–79.

Grant, J. et al. A monolithic resonant Terahertz sensor element comprising a metamaterial absorber and micro-bolometer. Laser Photonics Rev. 7 (6), 1043–1048 (2013).

Carranza, I. E. et al. Metamaterial-based Terahertz imaging. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 5 (6), 892–901 (2015).

He, Z. et al. Graphene-based metasurface sensing applications in Terahertz band. Results Phys. 21, 103795 (2021).

He, X. et al. High-sensitive dual-band sensor based on microsize circular ring complementary Terahertz metamaterial. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 31 (1), 91–100 (2017).

Islam, M. S. et al. Sensing of toxic chemicals using polarized photonic crystal fiber in the Terahertz regime. Opt. Commun. 426, 341–347 (2018).

Jiu-sheng, L. Mu-shu, Manipulation Terahertz wave with electro-rheological fluid. Opt. Commun. 475, 126244 (2020).

Han, B. et al. A sensitive and selective Terahertz sensor for the fingerprint detection of lactose. Talanta 192, 1–5 (2019).

Ramachandran, A., Babu, P. R. & Senthilnathan, K. Design of a Terahertz chemical sensor using a dual steering-wheel microstructured photonic crystal fiber. Photonics Nanostructures-Fundamentals Appl. 46, 100952 (2021).

Wang, L. Terahertz imaging for breast cancer detection. Sensors 21 (19), 6465 (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. Terahertz spectral unmixing based method for identifying gastric cancer. Phys. Med. Biol. 63 (3), 035016 (2018).

Shi, W. et al. Detection of living cervical cancer cells by transient Terahertz spectroscopy. J. Biophotonics. 14 (1), e202000237 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Label-free diagnosis of ovarian cancer using spoof surface plasmon polariton resonant biosensor. Sens. Actuators B. 352, 130996 (2022).

Banerjee, S. et al. Skin Cancer Detection Using Terahertz Metamaterial Absorber and Machine Learning (IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, 2025).

Zhan, X. et al. Streptavidin-functionalized Terahertz metamaterials for attomolar Exosomal MicroRNA assay in pancreatic cancer based on duplex-specific nuclease-triggered rolling circle amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 188, 113314 (2021).

Geng, Z. et al. A route to Terahertz metamaterial biosensor integrated with microfluidics for liver cancer biomarker testing in early stage. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 16378 (2017).

Tümkaya, M. A., Karaaslan, M. & Sabah, C. Metamaterial-based fluid sensor for identifying different types of fuel oil samples. Chin. J. Phys. 56 (5), 1872–1878 (2018).

Tümkaya, M. A. et al. Sensitive metamaterial sensor for distinction of authentic and inauthentic fuel samples. J. Electron. Mater. 46, 4955–4962 (2017).

Agarwal, S. & Prajapati, Y. Metamaterial based sucrose detection sensor using transmission spectroscopy. Optik 205, 164276 (2020).

Nie, P. et al. Sensitive detection of Chlorpyrifos pesticide using an all-dielectric broadband Terahertz metamaterial absorber. Sens. Actuators B. 307, 127642 (2020).

Gulsu, M. S. et al. Metamaterial-based sensor with a polycarbonate substrate for sensing the permittivity of alcoholic liquids in a WR-229 waveguide. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 312, 112139 (2020).

Abdulkarim, Y. I. et al. Determination of the liquid chemicals depending on the electrical characteristics by using metamaterial absorber based sensor. Chem. Phys. Lett. 732, 136655 (2019).

Hosseini, A. & Massoud, Y. A low-loss metal-insulator-metal plasmonic Bragg reflector. Opt. Express. 14 (23), 11318–11323 (2006).

Ebrahimi, A. et al. High-sensitivity metamaterial-inspired sensor for microfluidic dielectric characterization. IEEE Sens. J. 14 (5), 1345–1351 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. Terahertz dual-band metamaterial absorber for trace indole-3-acetic acid and Tricyclazole molecular detection based on spectral response analysis. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 263, 120222 (2021).

Veeraselvam, A. et al. A novel multi-band biomedical sensor for THz regime. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53, 1–20 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Terahertz microfluidic sensing with dual-torus toroidal metasurfaces. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9 (15), 2100024 (2021).

Qureshi, S. A. et al. Millimetre-wave metamaterial-based sensor for characterisation of cooking oils. Int. J. Anten. Propag. 2021 1–10. (2021).

Khalil, M. A. et al. Liquid chemical adulteration detection enhancement using a square enclosed Tri-Circle negative index metamaterial sensor. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 48, 101582 (2023).

Bhati, R. & Malik, A. K. Detection of several microorganism using Terahertz metamaterial perfect absorber. In CLEO: Science and Innovations. (Optica Publishing Group, 2023).

Bhati, R., Jewariya, M. & Malik, A. K. Spoof surface plasmon-based Terahertz metasensor for glucose and ethanol. Appl. Phys. A. 128 (9), 840 (2022).

Gutiérrez, Y. et al. Plasmonics beyond noble metals: exploiting phase and compositional changes for manipulating plasmonic performance. J. Appl. Phys. 128 (8). (2020).

Choudhury, S. M. et al. Material platforms for optical metasurfaces. Nanophotonics 7 (6), 959–987 (2018).

AZoM Gold - physical, mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleId=5147 (2022).

Rahman, M. et al. Symmetric engineered central cross-shaped broadband metamaterial absorber with high absorption and stability for solar sailing and solar energy applications. Surf. Interfaces 105077. (2024).

Wikipedia Relative permittivity. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relative_permittivity (2024).

Jafari, A. K. et al. Effects of silicon dioxide as the Polar dielectric on the infrared absorption spectrum of the metal-insulator-metal metasurface. Mater. Res. Express. 10 (1), 015801 (2023).

Xu, W. et al. Metamaterial-free flexible graphene-enabled Terahertz sensors for pesticide detection at bio-interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12 (39), 44281–44287 (2020).

Li, F. et al. The Terahertz metamaterials for sensitive biosensors in the detection of ethanol solutions. Opt. Commun. 475, 126287 (2020).

Upender, P. & Kumar, A. THz dielectric metamaterial sensor with high Q for biosensing applications. IEEE Sens. J. 23 (6), 5737–5744 (2023).

Dayal, G. et al. High-Q plasmonic Fano resonance for multiband Surface‐Enhanced infrared absorption of molecular vibrational sensing. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5 (2), 1600559 (2017).

Aouani, H. et al. Plasmonic Nanoantennas for multispectral surface-enhanced spectroscopies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117 (36), 18620–18626 (2013).

Mahmud, S. et al. A multi-band near perfect polarization and angular insensitive metamaterial absorber with a simple octagonal resonator for visible wavelength. IEEE Access. 9, 117746–117760 (2021).

Lari, E. S., Vafapour, Z. & Ghahraloud, H. Optically tunable triple-band perfect absorber for nonlinear optical liquids sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 20 (17), 10130–10137 (2020).

Hakim, M. L. et al. Polarization insensitivity characterization of dual-band perfect metamaterial absorber for K band sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 17829 (2021).

Tian, J. et al. Tunable quad-band perfect metamaterial absorber on the basis of monolayer graphene pattern and its sensing application. Results Phys. 26, 104447 (2021).

Rahman, M. et al. Design Of A Broadband Metamaterial Absorber With Incident Angle Stability And Polarization Insensitivity For Solar Energy Application In The Visible Spectrum. in. 3rd International Conference on Advancement in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ICAEEE). 2024. IEEE. (2024).

Hakim, M. L. et al. Polarization insensitive symmetrical structured double negative (DNG) metamaterial absorber for Ku-band sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 479 (2022).

Contributors, W. Fresnel equations. ; (2019). Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fresnel_equations

Zhou, F. et al. Ultra-wideband and wide-angle perfect solar energy absorber based on Ti nanorings surface plasmon resonance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23 (31), 17041–17048 (2021).

Tayebjee, M. J., McCamey, D. R. & Schmidt, T. W. Beyond Shockley–Queisser: molecular approaches to high-efficiency photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6 (12), 2367–2378 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Vapor-deposited amorphous metamaterials as visible near-perfect absorbers with random non-prefabricated metal nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 4 (1), 4850 (2014).

Nishijima, Y. et al. Tailoring metal and insulator contributions in plasmonic perfect absorber metasurfaces. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1 (7), 3557–3564 (2018).

Janneh, M. et al. Design of a metasurface-based dual-band Terahertz perfect absorber with very high Q-factors for sensing applications. Opt. Commun. 416, 152–159 (2018).

He, X. et al. Tunable strontium titanate Terahertz all-dielectric metamaterials. J. Phys. D. 53 (15), 155105 (2020).

Geng, Z. et al. Numerical design of a metasurface-based ultra-narrow band Terahertz perfect absorber with high Q-factors. Optik 194, 163071 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. A high Q-factor dual-band Terahertz metamaterial absorber and its sensing characteristics. Nanoscale 15 (7), 3398–3407 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. Metamaterial microwave sensor with ultrahigh Q-factor based on narrow-band absorption. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 364, 114779 (2023).

Nickpay, M. R., Danaie, M. & Shahzadi, A. Design of a graphene-based multi-band metamaterial perfect absorber in THz frequency region for refractive index sensing. Phys. E: Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 138, 115114 (2022).

Ma, H. et al. Laminated Hybrid Metamaterial Block for Enhanced Efficiency and SNR in Simultaneous Wireless Power and Signal Transmission System with Dual-Sided LCCL Compensation Networks (IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Sensitive detection of cancer cell apoptosis based on the non-bianisotropic metamaterials biosensors in Terahertz frequency. Opt. Mater. Express. 8 (3), 659–667 (2018).

Li, D. et al. Identification of early-stage cervical cancer tissue using metamaterial Terahertz biosensor with two resonant absorption frequencies. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 27 (4), 1–7 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Design of pixel Terahertz metamaterial absorber sensor based on an improved ant colony algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. (2024).

Deng, G. et al. A metamaterial-based absorber for liquid sensing in Terahertz regime. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (22), 21659–21665 (2022).

Abdulkarim, Y. I. et al. Highly sensitive dual-band Terahertz metamaterial absorber for biomedical applications: simulation and experiment. ACS Omega. 7 (42), 38094–38104 (2022).

Tang, P. et al. Ultrasensitive specific Terahertz sensor based on tunable plasmon induced transparency of a graphene micro-ribbon array structure. Opt. Express. 26 (23), 30655–30666 (2018).

Ge, J. et al. Tunable dual plasmon-induced transparency based on a monolayer graphene metamaterial and its Terahertz sensing performance. Opt. Express. 28 (21), 31781–31795 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. A Terahertz metamaterial sensor used for distinguishing glucose concentration. Results Phys. 26, 104332 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Highly sensitive Terahertz dielectric sensor for liquid crystal. Symmetry 14 (9), 1820 (2022).

Hoque, A. et al. SNG and DNG meta-absorber with fractional absorption band for sensing application. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 13086 (2020).

Hamza, M. N. et al. Development of a high-sensitivity triple-band nano-biosensor utilizing Petahertz metamaterials for optimal absorption in early-stage leukemia detection. IEEE Sens. J. (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Research Grant through the Geran Universiti Penyelidikan (GUP) under the grant number GUP-2022-007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sazzad Ahmed: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, writing original draft preparation. Touhidul Alam: Conceptualization, Software, writing review and editing, and Supervision.Md Mohiuddin Soliman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, writing original draft preparation, and writing review and editing.Md Mushfiqur Rahman: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, writing draft preparation, writing review and editing.Asraf Mohamed Moubark: Writing review and editing, Project administration, and Funding acquisition.Md. Shabiul Islam: Writing review and editing, Project administration, and Funding acquisition.Mohammad Tariqul Islam: Formal analysis, writing review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, S., Alam, T., Soliman, M.M. et al. Enhanced structural tunability and high sensitivity of a THz metasurface absorber for precise automotive fuel characterization. Sci Rep 15, 22996 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05326-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05326-0