Abstract

Demographic transition has led to a progressive increase in the proportion of elderly and very elderly patients. This population shift implies a growing demand for health resources, including intensive care, despite the high mortality rates associated with this age group in ICUs. To determine the clinical characteristics and outcomes of a population of critically ill elderly patients (≥ 90 years) admitted to the ICU and to identify predictive factors associated with mortality. This retrospective observational study analyzed data from critically ill elderly patients (≥ 90 years) admitted to the Intensive Medicine Service of a tertiary hospital in São Luís, MA, between 2021 and 2022. Demographic, clinical, treatment, and outcome data were collected, and statistical analysis was used to determine independent predictors of mortality. Of the 3551 patients admitted, 269 (≥ 90 years old) were included. The majority were female (69.5%), with a high prevalence of comorbidities. The emergency department was the main origin of patient admission (87%). The most frequent diagnostic category upon ICU admission was infection/sepsis. The median duration of ICU stay was seven days, and the median hospital stay was 15 days. The hospital mortality rate was 27.5%, and the ICU mortality rate was 17.8%. The use of mechanical ventilation and dialysis on the first day in the ICU was independently associated with increased mortality. Critically ill elderly patients (≥ 90 years) have a high prevalence of comorbidities, and specific interventions, such as mechanical ventilation and dialysis on the first day of the ICU, are predictors of mortality. Compared with other case series, the observed mortality was not high, suggesting that chronological age alone should not be a criterion for limiting access to intensive care. Decisions regarding triage (i.e., identifying which older adults are most likely to benefit from ICU-level care) and treatment limitations are crucial in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to demographic changes, the proportion of elderly and very elderly patients is progressively increasing1. The global population is aging at an unprecedented rate, with projections indicating that by 2050, there will be approximately 2 billion people over the age of 65 worldwide2.

In the past 15 to 20 years, there has been a growing demand for intensive care among very elderly patients3. These population trends will lead to an increased demand for healthcare resources (in terms of both bed capacity and healthcare professionals), including intensive care. Medical advances now enable elderly patients to undergo procedures and surgeries that were not viable a few decades ago owing to age. As a result, more very elderly patients are being admitted to intensive care units (ICUs)4. In this context, intensive care units (ICUs) are facing increasing demand, with elderly patients now representing 20 to 30% of all admissions5.

Studies focusing on very elderly patients (≥ 90 years) admitted to ICUs remain relatively scarce, although recent publications have begun to address this gap6,7. Nearly every country is confronting an increasingly aging population, making it crucial to address the current knowledge gaps in this specific group. Nevertheless, epidemiological data on very elderly ICU patients are still largely limited to specific geographic regions, underscoring the need for broader, more comprehensive research efforts in this area8.

Thus, the main objective of this study was to determine the clinical characteristics and outcomes of a population of critically ill elderly patients (≥ 90 years) admitted between 2021 and 2022 to a tertiary hospital’s intensive care unit (63 beds).

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective observational study of adult patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of a tertiary hospital between 2021 and 2022. The Hospital and Maternity São Domingos Ethics Committee approved the study under opinion number 6.202.436 and CAAE number 70535623.5.0000.5085. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed consent.

Setting

It was conducted at the intensive care unit of a private, high-complexity tertiary hospital located in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil, with a total of 63 ICU beds.

Participants

All patients aged ≥ 90 admitted to the ICU between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2022, were eligible for inclusion in the study. If a patient was admitted to the ICU multiple times, only data from the first ICU admission were analyzed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was hospital mortality. The secondary outcome measures included (1) ICU mortality; (2) resource utilization assessed by length of stay in the ICU or hospital; (3) the proportion of patients who had one or more ICU readmissions during the same hospitalization; and (4) the discharge destination of survivors (home/rehabilitation/long-term care/nursing homes).

Variables studied

The following data were extracted from the hospital’s electronic patient management system: age, sex, place of residence, presence of advanced directives, primary reason for admission, comorbidities, length of stay in the ICU and hospital, treatment modalities and organ support (mechanical ventilation, use of catecholamines, renal replacement therapy, blood transfusions), discharge information (post-ICU and post-hospital destination), ICU and hospital mortality, and treatment limitation decisions. ICU and hospital mortality rates were also analyzed.

Comorbidities were calculated using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)9. Frailty was assessed by the Modified Frailty Index (mFI)9. Preadmission functional status (one week prior to ICU admission) was also evaluated via the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scale10. Disease severity was calculated using the simplified acute physiology score 3 (SAPS 3), which is a prognostic tool designed to predict outcomes in ICU11. The definitions of each variable are listed in Table 1.

Statistical methods

Descriptive analysis of qualitative variables provided absolute and relative frequencies, whereas quantitative variables were described via location parameters (mean and median) and dispersion parameters (standard deviation). The normality of distributions was assessed via the Shapiro‒Wilk or Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test.

Associations between qualitative variables were evaluated via the chi-square test with Yates correction. Comparisons between qualitative and quantitative variables were performed via the Mann‒Whitney U test. For significant variables, logistic regression models with 95% confidence intervals were used to estimate independent predictors of ICU and hospital mortality. The significance level was set at 5%. Analyses were performed via SPSS Statistics 26 software.

Results

Clinical characteristics

During the study period, 3551 patients were consecutively admitted to the ICU. Among these patients, 269 patients (7.5%) aged ≥ 90 years were included in the analysis. The mean age of the study population was 93.12 years (95% CI 92.77–93.46). The predominant age group was 90–95 years (82.5%), followed by the 95–100 years age group (14.5%). Only 8 patients (3%) were aged ≥ 100 years. The majority of the patients were female (69.5%), as shown in Table 2.

Regarding comorbidities, 208 patients (80.3%) had two or more comorbidities. Chronic cardiovascular diseases were the most prevalent (88.8%), followed by chronic respiratory diseases (13.3%). In this population, 76 patients (28.3%) were considered frail, as measured by the modified frailty index (mFI). Approximately half of the patients required some degree of assistance, and 33.7% were classified as restricted.

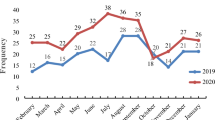

Concerning the source of ICU admission, 234 patients (87%) were admitted from the emergency department, 23 patients (8.5%) from the surgical/hemodynamic center, and 12 patients (4.5%) from the hospital ward. Admissions were predominantly medical, accounting for 244 patients (90.7%). The remaining admissions were surgical, with 12 (4.5%) being elective surgeries and 13 (4.8%) being urgent/emergency surgeries. The major diagnostic category upon ICU admission was infection/sepsis, affecting 149 patients (55.4%), followed by cardiovascular (13%), neurological (9.3%), and respiratory (3.3%) conditions, among others, as shown in Table 2. Only 23 patients were admitted to the ICU with a COVID-19 diagnosis, representing 8.6% of the total cases. In addition to the low prevalence in the study population, a COVID-19 diagnosis was not associated with increased hospital mortality (see Table 6).

Severity

The severity of the disease in the study population is shown in Table 3. The mean SAPS-3 severity score was 58.04 (95% CI 56.61–59.47), and the predicted mortality rate for this population, derived from the SAPS-3 score, was 33.54% (mean, with a standard deviation (SD) of 19.48). The rate of mechanical ventilation use on the first day in the ICU (D1) was 25.7%. Twenty-four patients experienced cardiac arrest on D1, accounting for 9.1% of the sample, as shown in Table 3. Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) was used in 67 patients (25.3%). Sixty patients (22.6%) required vasopressors on ICU day 1.

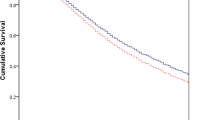

Primary and secondary outcomes

In terms of the primary outcome, hospital mortality was 27.5%, corresponding to 74 patients. For the secondary outcomes, the ICU mortality rate was 17.8%, corresponding to 48 patients. The mean ICU length of stay was 12.01 days (95% CI 9.87–14.15), with a median of 7 days. The mean hospital length of stay was 24.84 days (95% CI 21.26–28.42), with a median of 15 days. The ICU readmission rate during the study period was 18.6%, with 50 episodes, as shown in Table 4. Treatment limitation decisions were made for only 10 patients (3.8%). ICU mortality was higher among medical patients (17%) than among surgical patients (0.7%). This trend was also observed for hospital mortality.

Mechanical ventilation use on ICU day 1 (D1) was independently associated with increased ICU mortality (OR 17.34, 95% CI 8.16–36.84, p < 0.001) and hospital mortality (OR 9.57, 95% CI 5.11–17.93, p < 0.001). Dialysis at ICU admission was also associated with increased ICU mortality (OR 28.48, 95% CI 6.38–12.97, p < 0.001). However, this effect was not observed for hospital mortality, as shown in Tables 5 and 6. Treatment limitation decisions were associated with higher hospital mortality (OR 6.92, 95% CI 1.73–27.5, p = 0.002), as was age (OR 1.02 95% CI 0,93 − 1,11, p = 0.017).

The majority of ICU survivors (182 patients – 67.6%) were discharged to the hospital ward. A small proportion (5.6%, or 15 patients) were discharged directly to home care. Other discharge destinations are detailed in Table 4.

Discussion

Many ICUs worldwide face the growing challenge of admitting elderly patients, often referred to as very old intensive care patients (VIPs), defined in the international literature as patients aged ≥ 80 years12. As reflected in this study, approximately 7.5% of critically ill patients admitted to a general intensive care unit were aged over 90 years, over two consecutive years. We chose this age group because few studies have focused on this population in the literature.

Chronological age alone should not be a criterion for ICU admission limitations. Instead, biological age, an achievable therapeutic goal, and the patient’s wishes should play key roles in the decision-making process1. Biological age does not necessarily equate to chronological age and is more difficult to assess. Therefore, the focus is gradually shifting from traditional comorbidity measures to the concept of frailty as an important marker of biological age and a predictor of outcomes13. Frailty, as a concept, is relatively new in intensive care and is often defined as a clinical state of increased susceptibility to age-related declines in reserve and function across a wide range of physiological systems14.

As evidenced by the VIP 1 study12, which included 5021 patients aged ≥ 80 years in Europe, frailty, age, and SOFA score were independently associated with increased 30-day mortality in this population. In the VIP 2 study15, frailty, cognitive decline and disability were strongly associated with 30-day mortality and were more important than age alone. Thus, chronological age should not necessarily be the sole determinant for ICU admission.

In our study, the prevalence of frailty, as measured by the mFI, was 28.3%. This condition was not associated with increased ICU or hospital mortality, in contrast to findings from studies such as VIP 1 and VIP 2. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that we assessed frailty using an index based on specific, pre-existing diagnoses rather than a direct, multidimensional evaluation of the patient. This measurement approach may underestimate important aspects of functional, cognitive, and nutritional status, which are fundamental components of frailty. Furthermore, our smaller sample size may have limited our statistical power to detect significant differences. Therefore, the absence of an association between frailty and outcomes in our cohort should be interpreted with caution, acknowledging the inherent limitations of the measurement method used and the study’s sample size.

On the other hand, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)9 was associated with higher hospital mortality and an increased rate of ICU readmission (p < 0.001). However, we must consider that ≥ 2 simultaneous comorbidities were highly prevalent in this study. Chronic cardiovascular comorbidities were the most common. A similar result was observed in a European cohort, where 94% of patients had cardiovascular comorbidities16. Additionally, approximately 83% of patients in our study exhibited some degree of functional dependence before hospital admission, as assessed by the ECOG PS scale (see Table 1).

The hospital mortality rate observed in this study was 27.5%, and the ICU mortality rate was 17.8%. A French study reported a hospital mortality of 42.6% and an ICU mortality of 35.7% in a population of patients aged ≥ 90 years16. The VIP study, which included patients aged ≥ 80 years, reported an ICU mortality of 22.1%, with a 30-day mortality of 35%. A prospective Canadian cohort reported ICU and 30-day mortality rates of approximately 21.8% and 35%, respectively17. In a retrospective German cohort of patients aged ≥ 90 years (mostly admitted for medical reasons and from the emergency department), hospital and ICU mortality rates were 30.9% and 18.3%, respectively1.

In addition to these findings, a recent single-center German study of patients aged ≥ 90 years reported stable short-term outcomes over time (ICU mortality of 18% and hospital mortality of ~ 30%) but noted an overall increase in admissions of very elderly individuals, alongside improvements in 1-year survival7. Furthermore, a large multicenter cohort from Australia and New Zealand focusing on patients aged ≥ 80 years demonstrated that although very elderly patients exhibited higher ICU and hospital mortality rates than younger cohorts, they also experienced a faster decline in risk-adjusted mortality over a 13-year period6. These observations highlight that older patients, particularly those ≥ 80 or 90 years, may be selected more carefully for ICU admission over time, and improvements in critical care practices could be contributing to better long-term outcomes.

On the other hand, the higher mortality rates reported in those studies6,7 might reflect differences in patient selection, triage processes, or admission thresholds across healthcare systems, which could partially explain the relatively lower mortality observed in our cohort. Likewise, our broader inclusion criteria may have captured a less severely ill subgroup, thereby influencing the overall mortality rates. These factors underscore the importance of considering admission practices, patient characteristics (medical vs. surgical, planned vs. unplanned admission), and evolving critical care approaches when comparing outcomes among very elderly ICU patients.

As a general intensive care service, most admissions in our study came from the emergency department (87%), indicating acute causes. Most patients were admitted for medical reasons (90.7%). The infection/sepsis category was the main diagnostic reason for ICU admission. In a German study involving 372 patients aged ≥ 90 years admitted to the ICU, approximately 67% of patients came from the emergency department, but trauma was the primary diagnostic feature1.

A low number of COVID-19 cases was identified in this cohort. Patients were classified as having COVID-19 only when a laboratory-confirmed test was available. Consequently, cases with clinical suspicion but without testing or with negative results may have been recorded under alternative diagnoses such as sepsis or acute respiratory failure, leading to potential underestimation. Additionally, during the later phases of the pandemic (2021 and 2022), a higher proportion of younger patients with COVID-19 was observed at our center, whereas the first wave (2020) saw more elderly patients. This shift in the patient profile may also have contributed to variations in diagnostic classification over time.

Despite the low proportion of surgical patients (urgent or elective), accounting for approximately 10% of the sample, we observed higher mortality, both in the ICU and hospital, among medical patients than among surgical patients, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.189). Other studies have reported better outcomes in the scheduled surgery group among very elderly patients. Additionally, unplanned surgery admission is a predictor of poor outcomes18. The severity of acute illness may partially explain the differences in mortality among the three subgroups.

The mean SAPS3 score for the study population was 58. A validation study of this score in Brazil involving approximately 50,000 critically ill patients reported a mean SAPS3 score of 44.3 ± 15.4 points19. This highlights the greater severity in our population than in the Brazilian average population. For the ICU length of stay, our sample had a mean duration of 15 days, with a median of 7 days. A French study of patients aged ≥ 90 years reported a mean ICU stay of 7 days16. An Australian cohort involving patients aged ≥ 80 years, outside the age cutoff of our study, reported a shorter median ICU stay of 1.8 days6.

A key discussion point concerns the limitation of life sustaining therapies (LLST) in this population, as well as decisions related to palliative care. In our study, no patients had a documented advance directive before ICU admission. A study conducted with palliative care teams in Brazil revealed that challenges such as legal issues, lack of knowledge among healthcare professionals, absence of institutional protocols, difficulty in discussing death, and family resistance contribute to decision-making challenges20.

The challenges in decision-making for very elderly patients have increased in both quantity and complexity. In parallel with demographic aging, there has been significant progress in treating previously fatal conditions, such as metastatic cancer. This has led to an increase in the influx of complex patients on the one hand and persistent enthusiasm for advanced organ support technologies on the other hand21. Decision-making in the ICU is primarily based on clinical trial conclusions, which often focus on single interventions and do not consider the burden of therapy or individual perspectives on quality of life (QoL). Additionally, the challenges posed by heterogeneous multimorbidity in the context of geriatric conditions have yet to be adequately integrated into previous ICU trials22.

A low number of treatment limitations after ICU admission was observed. Becker et al. demonstrated that 17.5% of patients aged ≥ 90 years had an advance directive. In the same study, treatment limitation decisions were made for 92 patients (24.7%)1. Le Borgne et al. reported a rate of 33.4% for treatment limitation decisions in the same age group, with 17% of patients having an advance directive16. Notably, the intensive care service in this study did not have an established palliative care service integrated into the ICU with institutionalized protocols. Cultural barriers among healthcare teams and the patient/family population may also have contributed to the low number of patients with treatment limitations.

The ICU readmission rate (at any time during the same hospital stay) was 18.6%, corresponding to 50 patients. In a retrospective Australian cohort involving approximately 233,000 critically ill patients aged ≥ 80 years, the ICU readmission rate was 4.7%6. ICU readmissions are associated with worse patient outcomes, including hospital mortality and prolonged length of stay23. This is associated with worse patient outcomes, including hospital mortality and prolonged length of stay22. The higher ICU readmission rate in our study may have resulted from the greater clinical vulnerability of these patients, given the high number of comorbidities, as well as issues related to the level of support provided in the ward environment.

Our results should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, our single-center study provides findings that may need to be more generalizable to contexts where ICU availability and population profiles differ. Second, we did not present follow-up data for the patients. Other studies have reported that both quality of life and autonomy in activities of daily living among elderly ICU survivors are considered satisfactory24. Third, the retrospective nature of the study may introduce selection bias, as patient inclusion was based on preexisting medical records, which may contain inconsistencies or omissions, impacting the generalizability of the results. Fourth, the lack of detailed data on the severity of comorbidities (e.g., number of medications used and frequent exacerbations) and the pre-ICU functional status of patients may limit the understanding of the full impact of these variables on outcomes in very elderly ICU patients. Fifth, although we used the mFI to assess frailty, it is an indirect measure and may not fully capture the multidimensional nature of frailty, potentially limiting the accuracy of its association with clinical outcomes.

The data from this study suggest that chronological age is not the sole factor limiting the admission of these patients (≥ 90 years) to the ICU. Furthermore, they suggest that these patients, despite their advanced age, can benefit from intensive care.

Conclusion

Our single-center study demonstrated that critically ill elderly patients (≥ 90 years) have a high prevalence of comorbidities, as well as elevated severity, upon ICU admission. The use of mechanical ventilation and dialysis on the first day of ICU admission were predictors of both ICU mortality and hospital mortality. Compared with those in other case series, mortality rates in the ICU and hospital were not high. Admission triage decisions, as well as treatment limitations, are essential aspects of this population. Cultural barriers exist and need to be addressed.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- EAPC:

-

European Association for Palliative Care

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- EUGMS:

-

European Union Geriatric Medicine Society

- ICC:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- mFI:

-

Modified Frailty Index

- SAPS3:

-

simplified acute physiology score 3

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TLT:

-

Time-Limited Trial

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

References

Becker, S. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of very elderly patients ≥ 90 years in intensive care: a retrospective observational study. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 5 (1), 53 (2015).

Mitchell, E. & Walker, R. Global ageing: successes, challenges and opportunities. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond). 81 (2), 1–9 (2020).

Cobert, J. et al. Trends in geriatric conditions among older adults admitted to US ICUs between 1998 and 2015. Chest 161 (6), 1555–1565 (2022).

Guidet, B. et al. The trajectory of very old critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 50 (2), 181–194 (2024).

Bagshaw, S. M. et al. Very old patients admitted to intensive care in Australia and new zealand: a multi-centre cohort analysis. Crit. Care. (London, England). 13 (2), R45–R (2009).

Rai, S. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of very elderly patients admitted to intensive care: A retrospective multicenter cohort analysis. Crit. Care Med. 51 (10), 1328–1338 (2023).

Daniels, R. et al. Evolution of clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients 90 years old or older over a 12-Year period: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care Med. 52 (6), e258–e67 (2024).

Flaatten, H. et al. The status of intensive care medicine research and a future agenda for very old patients in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 43 (9), 1319–1328 (2017).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40 (5), 373–383 (1987).

Zampieri, F. G. et al. The effects of performance status one week before hospital admission on the outcomes of critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 43 (1), 39–47 (2017).

Metnitz, P. G. et al. SAPS 3–From evaluation of the patient to evaluation of the intensive care unit. Part 1: objectives, methods and cohort description. Intensive Care Med. 31 (10), 1336–1344 (2005).

Flaatten, H. et al. The impact of frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years). Intensive Care Med. 43 (12), 1820–1828 (2017).

López Cuenca, S. et al. Frailty in patients over 65 years of age admitted to intensive care units (FRAIL-ICU). Med. Intensiva (English Edition). 43 (7), 395–401 (2019).

Xue, Q. L. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 27 (1), 1–15 (2011).

Guidet, B. et al. The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European icus: the VIP2 study. Intensive Care Med. 46 (1), 57–69 (2020).

Le Borgne, P. et al. Critically ill elderly patients (≥ 90 years): clinical characteristics, outcome and financial implications. PLOS ONE. 13 (6), e0198360 (2018).

Ball, I. M. et al. A clinical prediction tool for hospital mortality in critically ill elderly patients. J. Crit. Care. 35, 206–212 (2016).

Andersen, F. H., Flaatten, H., Klepstad, P., Romild, U. & Kvåle, R. Long-term survival and quality of life after intensive care for patients 80 years of age or older. Ann. Intensive Care. 5 (1), 53 (2015).

Moralez, G. M. et al. External validation of SAPS 3 and MPM(0)-III scores in 48,816 patients from 72 Brazilian ICUs. Ann. Intensive Care. 7 (1), 53 (2017).

Nogario, A. C. D. et al. Implementation of early will directives: facilities and difficulties experienced by palliative care teams. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 41, e20190399 (2020).

Beil, M. et al. Limiting life-sustaining treatment for very old ICU patients: cultural challenges and diverse practices. Ann. Intensive Care. 13 (1), 107 (2023).

Whitty, C. J. M. et al. Rising to the challenge of multimorbidity. Bmj. 368. England p. l6964. (2020).

McNeill, H. & Khairat, S. Impact of intensive care unit readmissions on patient outcomes and the evaluation of the National early warning score to prevent readmissions: literature review. JMIR Perioper Med. 3 (1), e13782 (2020).

Tabah, A. et al. Quality of life in patients aged 80 or over after ICU discharge. Crit. Care. 14 (1), R2 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FS and PC conceived and designed the paper and wrote the first draft. FS, EC, CM, AV, JN, and PC reviewed the literature. All authors have read and critically revised the different versions and approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amado, F.S., Moura, E.C.R., Oliveira, C.M.B. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill elderly patients aged 90 years and older. Sci Rep 15, 20486 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05343-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05343-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Validity of ICU prognostic risk stratification tools in the oldest patients: a comparative analysis of clinical scores in a multicenter binational cohort

Journal of Anesthesia, Analgesia and Critical Care (2026)

-

Impact of frailty on in-hospital outcomes in nonagenarian ICU patients: a binational multicenter analysis of 8,220 cases

Critical Care (2025)