Abstract

Due to the random fluctuations in power experienced by high-temperature green electric hydrogen production systems, further deterioration of spatial distribution characteristics such as temperature, voltage/current, and material concentration inside the solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC) stack may occur. This has a negative impact on the system’s flexibility and the corresponding control capabilities. In this paper, based on the SOEC electrolytic cell model, a comprehensive optimization method using an adaptive incremental Kriging surrogate model is proposed. The reliability of this method is verified by accurately analyzing the dynamic performance of the SOEC and the spatial characteristics of various physical quantities. Additionally, a thermal dynamic analysis is performed on the SOEC, and an adaptive time-varying LPV-MPC optimization control method is established to ensure the temperature stability of the electrolysis cell stack, aiming to maintain a stable, efficient, and sustainable SOEC operation. The simulation analysis of SOEC hydrogen production adopting a variable load operation has demonstrated the advantages of this method over conventional PID control in stabilizing the temperature of the stack. It allows for a rapid adjustment in the electrolysis voltage and current and improves electrolysis efficiency. The results highlighted that the increase in the electrolysis load increases the current density, while the water vapor, electrolysis voltage, and H2 flow rate significantly decrease. Finally, the SOEC electrolytic hydrogen production module is introduced for optimization scheduling of energy consumption in Xinjiang, China. The findings not only confirmed that the SOEC can transition to the current load operating point at each scheduling period but also demonstrated higher effectiveness in stabilizing the stack temperature and improving electrolysis efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advancement of green and low-carbon development has driven progress toward global carbon reduction goals. With the rapid increase in the contribution of green electricity, it is important to consider the uneven spatial and temporal distribution of power grid supply and demand sides. In this regard, the coupling of green electricity and hydrogen is capable of enhancing the regulation capability of the holistic power system. As a potential alternative energy solution, the solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC) is characterized by a high energy conversion efficiency, reversibility, power variability, and stability. SOEC can be widely coupled with other alternative and new energy systems and implemented in various energy conversion and storage applications, such as power grid peak shaving and combined heat, electricity, and hydrogen generation systems1,2,3. In light of these developments, there is an urgent need to implement flexible load scheduling for green hydrogen production while ensuring the safe operation of SOEC units. However, the unstable stack temperature can cause uneven temperature distribution inside the electrolytic cell. This, in turn, affects the uniformity and efficiency of the electrolytic reaction process, along with deteriorating the performance of the electrolytic cell, shortening its lifespan, and increasing its safety hazards.

Many studies have resorted to lumped models or low-dimensional models for SOEC applications. For instance, Chi et al.4 discretized the three-dimensional (3D) space of the electrolysis cell stack to generate different control units. Then, they assigned each unit specific physical quantities, such as gas flow rate and temperature, to establish a two-dimensional model. This approach simplifies the complex 3D structure, but it may not accurately capture the detailed spatial distribution of physical phenomena within the SOEC. In addition, some researchers performed homogenization acceleration simulation modeling on the structure of the SOEC electrolysis cell stack, including the auxiliary equipment5,6. While they are computationally efficient, they lack the ability to precisely describe the spatial variation of heat and mass transfer, which are crucial for understanding the internal processes of SOECs. Other researchers7,8 utilized the principles of mass and energy conservation to develop lumped models with elements such as voltage sources, equivalent resistances, and capacitances. These models were used to simulate the volt-ampere characteristic curve inside the electrolytic cell. While they are computationally efficient, they lack the ability to precisely describe the spatial variation of heat and mass transfer, which are crucial for understanding the internal processes of SOECs. Some studies9,10,11 introduced complex low-level, low-dimensional sub-models into 3D models to reduce simulation degrees of freedom and computational complexity. However, these simplified models still struggle to fully represent the intricate operational characteristics of SOEC stacks, especially when it comes to the spatial distribution of physical quantities.

In an attempt to reduce simulation time, some researchers performed homogenization acceleration simulation modeling on the SOEC stack structure, including auxiliary equipment. This effectively decreased the number of grids and simulation time. Nevertheless, this simplification might sacrifice the accuracy of representing the detailed physical processes within the stack, making it difficult to analyze the multi-functional characteristics of SOEC stacks under different operating conditions. Many studies12,13,14 employed neural networks and polynomial functions to build relationships between temperature, material flow rate, current, voltage, and efficiency in an electrolysis system. On this basis, a PID controller was introduced to achieve current tracking control and ensure system voltage stability. Although PID controllers can provide a certain level of control, they face challenges in dealing with the complex and dynamic characteristics of SOEC systems. For example, the time-lag in heat transfer makes it difficult for PID controllers to precisely regulate the stack temperature, especially during rapid load changes. Li et al.15 and Xing et al.16 established SOEC stack aggregation models based on a multi-energy flow coupling system of electric heating and gas. These models were used to optimize the electrolysis hydrogen production efficiency and simulate partial loads. However, they often overlooked the dynamics during variable-load operation. In other studies17,18 various factors were considered and investigated in the development of a steady-state operating point model for SOECs. The examined factors include waste heat recycling, self-power loss, and convective heat transfer, while the dynamics during variable load operation were ignored.

3D models have the potential to accurately describe the dynamic operation of SOEC stacks and the spatial characteristics of physical quantities. But their high computational demands limit their application to single-operating-condition simulations. Zhang et al.19 integrated the spatiotemporal distribution of voltage and air pressure into multidimensional models, yet the extensive computations involved make these models unsuitable for optimizing and scheduling hydrogen-production systems. The existing research has several limitations. Simplified models, whether lumped or low-dimensional, fail to accurately represent the spatial distribution of physical quantities in SOECs20,21,22. Traditional control methods like PID are insufficient for precise temperature control in the face of complex system dynamics. Furthermore, the temperature dynamic response time of SOEC electrolysis systems typically spans several minutes. This complicates efforts to adjust the dynamic balance of the power grid on a second-by-second basis. On the other hand, the electrification response time of SOECs is typically several seconds, enabling them to indirectly adjust the multi-dimensional parameters of electrical and thermal gas output and achieve synchronous real-time tracking of dynamic electrical loads.

Based on the review and discussion presented above, this paper aims to accurately track the spatial distribution of physical quantities, such as temperature, current density, and material concentration inside the SOEC stack. To attain this, a SOEC accelerated 3D surrogate model is established, and an adaptive incremental Kriging surrogate model comprehensive optimization method is presented. The proposed method is verified, and its reliability is demonstrated. Additionally, a comprehensive analysis of the thermal dynamic characteristics of SOECs is conducted to address the non-steady state transition process of the SOEC green electricity hydrogen production system and to evaluate how the uneven distribution of various physical quantities within the stack creates thermal stress. This stress impacts the performance, stability, and hydrogen production efficiency of the electrolysis system. In this regard, a more advantageous control method is presented in comparison to a traditional PID control approach, proving more effective in stabilizing the temperature of the electrolysis cell stack. The proposed control method rapidly adjusts both the electrolysis voltage and current, leading to improved electrolysis efficiency.

SOEC 3D modeling

To comprehensively and accurately analyze the multi-space physical quantities of electrical and thermal gases involved in SOEC stack, a 3D model for SOECs is established in this study to further investigate the operating characteristics of SOECs in various scenarios and serve as a basis for selecting targeted optimization control strategies.

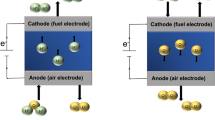

Stack structure

The SOEC stack structure, comprising an anode, electrolyte, cathode, and support body, is depicted in (Fig. 1), while its geometric parameters are listed in (Table 1). During high-temperature electrolysis, the two electrodes act as conductors for O2− and e−. The electrolyte facilitates the conduction of O2−, while the heating wire maintains the operating temperature throughout the electrolysis process. In the system operation, air is introduced at the oxygen electrode (anode), while water vapor and H2 are introduced at the hydrogen electrode (cathode) to protect the cathode from oxidation. Additionally, the support body on the anode side is divided into upper, middle, and lower sections based on the airflow direction. As the electrolysis reaction progresses, the concentration of water vapor in the cathode gradually decreases along the flow direction of incoming reactants. As a result, an uneven current distribution around the stack is experienced.

SOEC electrolytic cell model

The SOEC electrolytic cell model includes charge balance models that account for various physical quantities, as well as thermodynamic and kinetic models. It also incorporates models for fluid motion and material transfer processes, along with heat transfer models23,24,25,26,27,28.

Space charge model

Positive and negative charges are transferred between the electrolyte, composite current collector, and the two electrodes. Both the anode and cathode act as mixed conductors of e− and O2−, adhering to the law of conservation of charge. At the hydrogen electrode, the chemical reaction produces H2, while at the oxygen electrode, the reaction consumes O2−. The equations representing the reactions occurring at the anode and cathode electrodes are given by:

In accordance with the continuity of electric potential and the conservation of charge, the electric potential and normal vector of the conductor phase current density must satisfy the following conditions:

In Eq. (2), \(V_{{\text{o}}}\)(V) and \(V_{{\text{h}}}\)(V) denote the potentials of the conductor’s oxygen electrode and hydrogen electrode, respectively. N is the normal vector at the interface, while \(\varvec {I}_{{\text{o}}}\) and \(\varvec {I}_{{\text{h}}}\) represent the current density vectors for the conductor oxygen and hydrogen electrodes, respectively.

The overpotentials (\(\varphi _{{\text{o}}}\) and \(\varphi _{{\text{h}}}\)) at the same point within the space of the oxygen and hydrogen electrodes must satisfy the following conditions:

In Eq. (3), \(V_{{{\text{o,1}}}}\)(V) and \(V_{{{\text{o,2}}}}\)(V) represent the potentials of the electron conductor phase and ion conductor phase at the oxygen electrode, respectively. \(V_{{{\text{h,1}}}}\)(V) and \(V_{{{\text{h,2}}}}\)(V) denote the potentials of the electron conductor phase and the ion conductor phase at the hydrogen electrode, respectively. Also, \(E_{{\text{o}}}\)(V) and \(E_{{\text{h}}}\)(V) represent the respective reversible potentials of the conductor oxygen and hydrogen electrodes.

Thermodynamic and kinetic models

Thermodynamic analysis

From a thermodynamic perspective, the energy required for high-temperature electrolysis of water in an SOEC is composed of two components: thermal energy and electrical energy. On this basis, the energy equation for the new energy electrolysis reaction can be expressed as:

In Eq. (4), \(\Delta H\)(J/mol) is the total energy required for electrolysis, \(\Delta G\)(J/mol) is the Gibbs function required to provide electrical energy, \(T \Delta S\)(J/mol) is the heat conduction energy provided by the external environment, \(U_{{\text{r}}}\)(V) represents the theoretical decomposition voltage, \(U_{{\text{t}}}\)(V) is the heat-neutral voltage of electrolysis, z denotes the number of electron transfers required to produce one mole of H2, p is the pressure generated by a certain gas occupying the same volume of mixed gas, and B(C/mol) is Faraday’s constant.

Kinetic analysis

From a kinetic perspective, a high operating temperature can accelerate the electrode reaction rate and significantly reduce the polarisation overpotentials of the oxygen and hydrogen electrodes, which effectively reduces the polarisation loss in the electrolysis process.

The potential \(E_{{\text{r,H}}}\) of the reversible electrochemical reaction occurring on the hydrogen electrode side can be expressed as Eq. (5).

In Eq. (5), R(J/(mol·K)) is a constant in the ideal gas equation of state, \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} {\text{O}}}}\) is the mole fraction of water vapour in the gas mixture, \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} }}\) is the mole fraction of hydrogen in the gas mixture.

The reversible electrochemical reaction potential \(E_{{\text{r,O}}}\) occurring on the oxygen electrode side can be expressed as Eq. (6).

In Eq. (6), \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{O}}_{{2}} }}\) is the mole fraction of oxygen in the gas mixture.

Fluid flow and material transport model

Analysis of the fluid flow process

During the electrolysis reaction, water vapor and gas within the electrolysis cell diffuse into the flow channel and periphery of the electrodes. Throughout the reaction, the density of fluid i is denoted by ρ. An electrolysis cell fluid flow model is established in this study based on the momentum balance equation and mass balance equation, as detailed below:

In the above equations, \(\nu\) denotes the velocity vector, \(M_{{\text{i}}}\) is the source of spatial capacity quality, and \(\kappa\) is the viscosity of the fluid. \(\gamma _{{\text{p}}}\) and \(\gamma _{{\text{k}}}\) represent the electrodes’ porosity and fluid’s permeability, respectively, and \(m_{{\text{i}}}\)(kg/mol) denotes the molar mass of fluid i. \(\varepsilon _{i}\) is the fluid’s mole fraction, \(P_{{\text{p}}}\)(Pa) is the fluid pressure; T(℃) is the fluid temperature, and \(K_{R}\) is the ideal gas constant.

Analysis of the material transport process

In the analysis of the material transport process, the mass fraction (\(\mu _{i}\)) of fluid i in the porous electrode and channel should satisfy the following conditions:

Additionally, the fluid’s spatial capacity and mass source (Mi) should meet the following requirements:

In Eq. (10), A denotes the effective reaction area within the unit space capacity of the stack, while \(I_{{\text{o}}}\) and \(I_{{\text{h}}}\) represent the space capacity current sources at the anode and cathode, respectively.

Heat transfer model

In SOECs, the spatial heat source is typically distributed throughout the stack’s geometry. The space capacity heat source (Hi) generated by ion diffusion and electrochemical reactions includes ohmic overpotential heat, activated overpotential heat, and reversible electrochemical heat.

In Eq. (11), Ho, Hh and He denote the space heat sources of the anode, cathode, and electrolyte, respectively. Io,1 and Io,2 represent the potentials of the electron conductor phase at the oxygen electrode and the current density vector of the ionic conductor phase, respectively. Similarly, Ih,1 and Ih,2 are the respective potentials of the electron conductor phase at the hydrogen electrode and the current density vector of the ionic conductor phase. \(\varvec I_{{\text{e}}}\) is the current density vector of the electrolyte. \(\sigma _{{\text{o}}}\), \(\sigma _{{\text{h}}}\), and \(\sigma _{{\text{e}}}\) denote the conductivities of the oxygen electrode, hydrogen electrode, and electrolyte, respectively. \(\varphi _{{\text{o}}}\) and 1 represent the respective overpotentials of oxygen and hydrogen electrodes. \(\varphi _{{\text{h}}}\) is the entropy change of the electrolytic reaction of \(\Delta S\) mol of H2O.

SOEC 3D model conditional constraints

The boundary conditions of the SOEC 3D model are shown in (Table 2), where the temperatures of the upper, middle, and lower sections are the temperatures at the center of the corresponding support body. The controllable power supply is used to control the cell voltage to determine the currents of the upper, middle, and lower sections. The positive pole of the power supply is connected to the oxygen electrode side of the corresponding section, and the negative pole of the power supply is connected to the hydrogen electrode side. The cell voltage control range is from open circuit voltage to 1.55 V.

SOEC spatial model optimization and solution

As mentioned earlier, a SOEC 3D model can fully simulate the space’s physical quantities within the stack. However, the respective computational effort required to obtain the results is huge. To accurately simulate the spatial distribution of stack temperature, material flow rates, fluid concentrations, and other relevant physical quantities, an optimized surrogate model is employed. This approach reduces the computational complexity of the overall model. The result is an Adaptive Incremental Kriging surrogate model optimization that satisfies the constraint conditions. (This is abbreviated as the improved Kriging surrogate model, I-KSM in this study).

Model optimization

Augmented space

In the model development, the physical parameters are subject to augmented spatial constraints. The confidence region (\(R_{{\text{0}}}\)) of the respective deterministic variable, along with the spatial volume regions (\(R_{{\text{1}}}\)) and (\(R_{{\text{2}}}\)), which are derived from a tensor product, can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (12), n denotes the number of variables in the model.

The total augmented space (R) is expressed by the tensor product of the edge confidence region, as shown below:

Active learning Kriging surrogate model

Define the active region of the stack by the spatial repetitive expansion of a number of cell microelements. The temperature (T) is uniformly distributed inside this microelement structure, as is the distribution of the substance concentration inside the two electrodes. The electronic conductor phase potentials on the surface of the oxygen electrode and the surface of the hydrogen electrode are \(U_{{\text{c}}}\) and 0. The current source \(I_{{\text{h}}}\) on the hydrogen electrode side, the current source \(I_{{\text{o}}}\) on the oxygen electrode side, and the spatial capacity heat source \(H_{{\text{i}}}\) inside the microelement of this cell are solved according to the charge balance model, the thermodynamic and kinetic model, and the heat transfer model, and the spatial capacity mass source \(M_{{\text{i}}}\) for each substance is obtained using Eq. (10).\(\varepsilon_{{{\text{O}}_{{2}} }}\), \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} }}\), T, \(U_{{\text{c}}}\) are the inputs in the partial differential equations, and directly solving for the \(I_{{\text{h}}}\), \(I_{{\text{o}}}\), \(H_{{\text{i}}}\), \(M_{{\text{i}}}\) outputs in the stack model will increase the number of degrees of freedom of the system.

In order to reduce the number of meshes, degrees of freedom, and iterations of computation in the 3D model of the stack, and to speed up the 3D model simulation, it is proposed to embed the active learning Kriging surrogate model into the partial differential equations describing the spatial distribution of the electrodes. The active learning Kriging surrogate model is used to directly establish the nonlinear mapping relationship between the input quantities (\(\varepsilon_{{{\text{O}}_{{2}} }}\), \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} }}\), T, \(U_{{\text{c}}}\)) and the output quantities (\(I_{{\text{h}}}\), \(I_{{\text{o}}}\), \(H_{{\text{i}}}\), \(M_{{\text{i}}}\)), thus avoiding the computation of the partial differential equations describing the electric field.

The mass source is analysed by uniformly distributing it across the two electrodes and the electrolyte interface according to the principle of interfacial flux. The complexity of the spatial distribution of the electrodes is simplified by analysing the interfacial flux through active learning of the Kriging surrogate model. The driving surrogate equation for this stack microelement can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (14), \(I_{{{\text{cc}}}}\) and \(P_{{{\text{hh}}}}\) denote the area current density and heat generation density of the stack cells, respectively. \(J_{{{\text{H}}_{2} }}\), \(J_{{{\text{O}}_{2} }}\), and \(J_{{{\text{H}}_{{\text{2}}} {\text{O}}}}\) represent the respective mass flux surface densities of H2, O2, and H2O in the vertical direction of the interface.

To improve the fitting degree of the established Kriging model, both the local and the overall accuracy of the spatial model must be considered. In this study, the active learning method of double sampling on the optimization constraint interface is adopted. The learning equation for this method is expressed as follows:

In Eq. (15), \(f\)(.)>0, and sign(.) is a symbolic function. \(C(x)\) represents the normalized shortest distance from the current point. \(\xi _{1} (x)\) and \(\xi _{2} (x)\) are the prediction error and the predicted quantity of the existing point, respectively.

Taking into account the minimum response surface, the Kriging model with double sampling predicts the maximum value at the sampling point, as indicated in Eq. (16), with \(\hat{F}(x)\) representing the predicted value of the Kriging model.

Comprehensive optimization

To avoid overfitting during the double sampling process, the standard error is used to evaluate the global accuracy of the incremental Kriging model, considering its adaptive convergence, as presented by Eq. (17).

Additionally, to maintain balance among each sampling point, the system’s relative error convergence and stability should satisfy the criteria presented in Eq. (18), with S(.) representing the sample in the defect area.

During the sampling process, it is important to ensure that the double sampling points remain within a reasonable distance from each other. If the points are too close together and approximately overlapping, the computational effort will increase. The expression for this consideration is given in Eq. (19), with d denoting the Euclidean distance.

If the distance d is less than the threshold, the point does not align with the sampling criteria and is removed. However, if d is greater than or equal to the threshold, the sampling point meets the criteria and is kept.

Process methodology

Considering the active learning Kriging surrogate model features, such as double sampling, augmented space, and an adaptive optimization algorithm, the Kriging surrogate model is updated for each sampling point within the 3D space of interest to SOEC. The updated model is then optimized to guide the objective function optimization process, as shown in (Fig. 2). The steps of the process are detailed below:

Step 1: The initial sampling points on the augmented space are filtered, and the response function is calculated to establish the Kriging surrogate model.

Step 2: The spatial physical parameters are initialized, and the initial offset error of the constraint function is set to 0.

Step 3: The sampling points are incorporated into the defined augmented space, and an incremental Kriging surrogate model is established based on the interaction between the fluid and solid. The model is then continuously updated until the threshold for convergence is met.

Step 4: New sampling points are added for the failed sampling points and are filtered once more. By adopting the adaptive double sampling approach, a standard deviation increment Kriging surrogate model is constructed, meeting the accuracy requirements. At this stage, the offset error values of the reliability constraints are assessed. The convergence of the current iterative process is determined using the re-optimized constraints.

Step 5: For sampling points that have converged, the results are output; otherwise, Step 3 is conducted again and the process is continued.

Simulation results and experimental verification

The geometrical parameters of the 3D model in the simulations and experiments are shown in (Table 1), the boundary conditions are shown in (Table 2), and Table 3 shows the other relevant parameters in the model, with references to the literature3,22.

Simulation results

Comparison of effects

The SOEC stack involves the coupling of electrochemical reactions, heat and mass transfer, and other multi-physics fields, and its 3D model degrees of freedom are positively correlated with the number of stack. The degrees of freedom of a small single-cell stack reaches hundreds of thousands of levels, and the simulation takes several minutes, and when tens of cells are stacked, the degrees of freedom increase dramatically and the simulation takes several hours, which is beyond the carrying capacity of conventional computational resources. Large-scale/irregular stacks are difficult to meet the efficiency requirements of traditional simulation methods due to the complex grid division and the number of numerical iterations.

Navasa et al.29 adopted a homogenization method to simulate the effect of the original structure of the stack on the internal spatial physical parameters, thereby reducing the model meshing units and lowering simulation time. However, it did not consider the original complex structure of the stack and was only suitable for regular stack structures formed by stacking millimeter-level small battery cells. This approach was not applicable to larger or irregular stack structures, and its widespread adoption was limited. Ba et al.30 replaced some mathematical control equations of the 3D model with data-driven equations and utilized neural network models to fit these equations, aiming to reduce the simulation time of the stack model. However, the constructed model contained implicit expressions, which were difficult to directly embed into simulation software and restricted its practical application scope.

The integration of finite element method units into stack simulations enables seamless embedding of polynomial surrogate models within simulation software, significantly reducing computational time and resource consumption. As illustrated in Fig. 3, which compares the 3D spatial reference model with optimized configurations, the accelerated simulation method demonstrates substantial efficiency improvements. The simulation time of a single cell composed of the original model is more than three times the optimization simulation time, the simulation time of 3 cells original model is more than four times the optimization model simulation time, and the simulation time of 4 cells original stack is more than five times the optimization simulation time. The degree-of-freedom of the fuel cell stack model is positively correlated with the number of constituent cells, while the optimized model reduces degree-of-freedom by 30% compared to the original configuration. As the stack scale increases and more cells are stacked, the enhanced Kriging surrogate model achieves more pronounced reductions in Total grid complexity and Numerical iteration counts. Furthermore, optimized simulations exhibit progressively significant time savings as computational memory usage decreases during iterative workflows.

Accuracy comparison

At a temperature of 810 ℃, the SOEC electrolysis system uses the 3D spatial model as a benchmark to compare and evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of the lumped model and the optimized model (I-KSM) scheme. This comparison allows for an intuitive analysis and accurate description of the SOEC stack’s operational dynamics as well as the spatial characteristics of each physical quantity considered in the examination.

The distribution of the water vapor mole fraction (\(\varepsilon _{{{\text{H}}_{{\text{2}}} {\text{O}}}}\)) is presented in (Fig. 4). It is noted that the \(\varepsilon _{{{\text{H}}_{{\text{2}}} {\text{O}}}}\) distribution produced by the optimization model is almost entirely consistent with the simulation results of the benchmark model. Additionally, the \(\varepsilon _{{{\text{H}}_{{\text{2}}} {\text{O}}}}\) distribution generated by the lumped model showed a noticeable overshoot, revealing that the water vapor flow is minimal and primarily diffused. When \(U_{{\text{c}}} = 1.5{\text{V}}\), the water vapor in the upper section is almost consumed, resulting in a lack of timely supply of water vapor to the middle and low sections of the electrolytic hydrogen production.

Furthermore, when the SOEC electrolytic voltage is 1.3 V, the current density distribution on the intermediate interface of the electrolyte is presented in (Fig. 5). As shown in the results, the current intensity decreases in the direction of the fluid flow, and the current intensity at the symmetry of the flow channel and the rib plate is roughly equivalent. It is also noted that the current intensity perpendicular to the fluid direction exhibits circular fluctuations due to the raised rib structure.

In addition, Fig. 6 presents a comparison of the simulated SOEC current density distribution using different models. As shown in the figure, with a constant SOEC electrolytic voltage, the simulated SOEC current density distribution by the lumped model is more distorted than that provided by the optimized model. On this basis, the optimized model can accurately predict the current density at specific points, matching the current density obtained from the reference model. Moreover, as decreases, a corresponding decrease in the current density of the upper and middle sections is exhibited. It is also noted that when, more steam is consumed compared to the case with. However, due to the insufficient steam flow experienced at the lower section, an increase in the overvoltage of the electrochemical reaction is observed, and the current density at 1.3 V is greater than that at 1.5 V.

Figure 7 presents a comparison of the simulated variations in the temperature of the SOEC stack using different models. It is shown that the SOEC temperature variation obtained using the optimized model is consistent with the results reported from the benchmark model. Conversely, the temperature variation predicted by the lumped model shows some deviation from the reference curve. Additionally, it is noted that the temperature reported in the middle section is higher than that of the upper and lower sections, where the temperature in the upper section is the lowest among them. At the same time, at any point on the anode, the higher the electrolytic voltage, the larger the amount of heat generated in the electrolysis process, and the higher the stack temperature.

Experimental verification

Figure 8 shows the SOC stack testing platform. Due to the consumption of electrochemical reactions, the concentration of water vapor in the hydrogen side channel gradually decreases along the flow direction. A multi-stage structure (upper, middle, and lower sections) is adopted, combined with gas supply, stack temperature, and volt ampere characteristics, to verify whether the established three-dimensional model can predict the phenomena observed in the experiment. Embedding high-temperature and humidity sensors into specific sections (upper, middle, and lower sections) of the SOEC fuel cell, using a humidity generator to generate a known concentration of water vapor standard gas. In real-time monitoring, the sensor converts capacitance or resistance signals into mole fractions to achieve real-time monitoring of water vapor distribution in the stack. Air is introduced to the oxygen electrode side, while a mixture of H2 and water vapor generated by a bubbling humidifier is introduced to the hydrogen electrode side. An electric heating belt is wrapped around the pipeline between the humidifier and the battery to prevent condensation of water vapor inside the pipeline. Due to the fact that the conductivity of metal connectors is much higher than that of the battery itself, the metal support is approximated as an equipotential body. Use three controllable power sources to control the battery voltage and measure the current distribution on the battery. The positive poles of the three power sources are connected to three silver grids on the oxygen electrode side, while the negative poles are connected together to the silver grid on the hydrogen electrode side, which can reflect the current distribution characteristics of individual cells in a real stack. Small holes are drilled on the three metal supports on the oxygen electrode side for inserting thermocouples to measure the center temperature of the metal supports. The measured currents and temperatures upstream, midstream, and downstream are denoted as IU, IM, IL, TU, TM, and TL, respectively.

Figure 9 compares the water vapour molar fraction \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} {\text{O}}}} (g)\) distribution inside the SOEC stack under experiment and simulation. With the increase of the voltage of the stack, the water vapour distributions in the upper, middle and lower segments all decrease accordingly, with the largest decrease of \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} {\text{O}}}} (g)\) in the upper segment, which may be related to the higher gas flow rate and the greater intensity of electrochemical reaction in the inlet segment, followed by the second decrease of \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} {\text{O}}}} (g)\) in the middle segment, and the smallest decrease in the lower segment. Overall, the experimental and simulation results are highly consistent with each other, and the water vapour consumption is aggravated by the voltage increase, but the uneven temperatures and flow rates inside the reactor may lead to the difference in the degree of decrease in different sections.

Figure 10 compares the temperature distribution inside the SOEC stack under experiment and simulation. It can be seen that the middle section of the stack has the highest temperature, indicating that this section is the core area of the reaction, which accelerates the heat accumulation. The temperature of the lower section is the next highest, indicating that the gas flow rate near the exit decreases, leading to a decrease in the ability to carry heat. The temperature of the upper section is the lowest, indicating that the high-speed flow of the gas in the inlet section inhibits the temperature from increasing further. Overall, the experimental and simulation results are highly consistent, indicating that the thermal management model has accurately captured the internal heat transfer mechanism of the stack.

In the case where the water vapour utilisation does not affect the full section of the stack, Fig. 11 compares the SOEC stack volt-ampere characteristic curve under experiment and simulation. It can be seen that the current in the upper section of the cell is always the largest for the same voltage, indicating that the concentration of reactive gases at the inlet is larger, which reduces the activation polarisation loss and thus increases the current strength. The current in the lower section is the smallest, indicating that the water vapour concentration at the outlet is significantly reduced due to the consumption of the reaction in the upper section, which leads to an increase in concentration polarisation and inhibits the current density increase.

The results demonstrate that the proposed adaptive incremental Kriging surrogate model (I-KSM) based comprehensive optimization method achieves high accuracy in simulating multi-physics fields, including electrochemical reactions and coupled heat/mass transfer. By significantly reducing computational complexity, this method establishes an effective balance between accuracy and efficiency for SOEC simulations, demonstrating clear feasibility in medium-scale steady-state applications. However, its applicability to irregular stack geometries (e.g., non-uniform cell arrangements or unconventional flow channels) remains unverified. Notably, the accuracy of the I-KSM heavily depends on the selection of initial sampling points and the reliability of response function calculations. Inadequate sampling in critical regions (e.g., areas with steep temperature gradients or rapid gas concentration variations) may introduce prediction errors. Additionally, experimental input parameters (e.g., porosity and thermal conductivity in Table 3) containing measurement noise or operating outside the validated range could degrade model performance. While fluid flow and heat transfer are modeled via simplified governing equations (e.g., Eqs. (7), (8) for momentum and mass balance), such simplifications may neglect turbulent effects or phase changes (e.g., water condensation) observed in real-world systems.

Optimal control of SOEC considering nonuniformity

In general, the operating parameters of the system significantly influence the electrolytic voltage of the SOEC, the uniformity of space temperature distribution, and the steam utilization rate. Consequently, changes in these parameters impact the operational efficiency of hydrogen production via SOEC electrolysis. In addition, the temperature instability in the stack results in variable thermal stress. This, in turn, increases the stack’s failure rate, accelerates the degradation of the modular system, and shortens its service life. Thus, it is crucial to develop effective solutions to address the instability of SOEC electrolysis temperature during the load operation of green power conversion.

SOEC thermal dynamic analysis

In the electrolysis model system, the temperature of the electrolysis process can be improved through waste heat recovery, thereby increasing overall hydrogen production efficiency. Figure 12 illustrates the specific block diagram of the temperature control system. In the operational process, the circulating pump continuously moves the waste heat to the heat exchange system, and the temperature is measured and controlled to ensure optimal utilization of the system’s waste heat.

Heat conservation of source and load power

In the system’s operational state, the material is preheated and then heated by an electric furnace, until it reaches the operating temperature of the SOEC electrolysis system. This steady-state process involves both the conservation of source load power and heat. During SOEC electrolysis, electrical energy, electric furnace heat, and net heat exchange are transformed into chemical energy, conductive heat, and convective heat. Auxiliary equipment supplies the necessary heat required for SOEC electrolysis. The conservation data and states of the source load power heat during SOEC operation are detailed in (Table 4). In the table, K is the number of electrolytic cells and Pw denotes the load temperature rise power.

According to Table 4 and based on the macro energy conservation theorem of fluids and the principle of equivalent voltage, the sum of the stack heat and the net heat provided by auxiliary equipment equals zero. This indicates that the system is designed to meet the requirements for high-temperature electrolytic hydrogen production. The resulting optimization model for the high-temperature electrolytic hydrogen production system is as follows:

In Eq. (20), U1 is the preheating temperature rise voltage, U2 is the vaporization voltage, UL,min and represents the minimum voltage of the electric furnace during system electrolysis. Also, Ic,max denotes the maximum current that the electrolytic system can handle. λ is the waste heat recovery coefficient and Uw is the system temperature rise voltage.

Waste heat recovery

Based on the test data presented by Fu et al.2, the higher the temperature, the greater the efficiency of hydrogen production by electrolysis. Additionally, the variation in the module temperature is positively correlated with variations in the source load power. The parameters that define the temperature characteristics of the module are primarily thermal capacitance and thermal resistance. Therefore, the temperature variation of the electrolytic module can be obtained considering these two factors.

The working temperature (T) of the module is directly connected to the total heating power (Hheat) of the electrolytic reaction, the heat dissipation (Phd), and the heat carried away by the waste heat recovery system (Prec). These relationships are expressed as follows:

In Eq. (21), [J/(kg·K)] denotes the equivalent heat capacity, ∆(s) is the time step, R(Ω) is the equivalent resistance,T(t0) and is the room temperature.

Therefore, the core of analyzing the variations in the operational stage of the electrolytic module lies in examining it through temperature changes. In this regard, the respective states are the heat charging state, the heat releasing state, and the static heat storage equipment state. The different states of the electrolytic module are detailed in (Table 5).

To prevent damage to the electrolytic system, it is crucial to maintain the stack temperature and electrolytic current within a certain upper limit. In this regard, the preheating system must not only ensure complete vaporization of water but also exceed its heat-resistant peak value. Variations in the load during SOEC electrolytic hydrogen production can disrupt system temperature. This will prompt the temperature regulation system to adjust the electrolytic temperature close to the set value. While increasing the electrolysis temperature can enhance the electrolysis rate, excessively high temperatures sustained over time can shorten the system’s lifespan. The temperature variation of the electrolytic module can be described as an equivalent circuit, as shown in (Fig. 13), where temperature is analogous to the equivalent voltage at each node. The dynamic heat exchange within the electrolytic module can be represented by the thermal capacitor (C) and the thermal resistance (R). Additionally, the room temperature Tt(0) is set at a fixed value, which is equivalent to a DC voltage source. The total heating power (Hheat) from the electrolytic reaction is equivalent to a DC source. This source can adjust the voltage at each node, effectively controlling the module’s temperature.

Optimization control

The PID temperature control strategy for the SOEC stack can quickly respond to rapid load changes; however, due to the inherent time lag in heat transfer, the strategy struggles to eliminate the stack temperature fluctuations. To address this issue, model predictive control (MPC) is proposed to predict the electrolytic current and thermal dynamics of the system. By adjusting the electrolytic temperature of the SOEC stack in advance of load changes, MPC aims to minimize the output error and achieve stable operation of electrolytic temperature.

Thermal dynamic model

Furthermore, the high temperature required for the SOEC electrolytic hydrogen production system is usually supplied by the electric heating element within the electric furnace and by the heat transfer from high-temperature steam. To reduce power loss and avoid oxidation of the cathode, a high concentration of steam and hydrogen is introduced on the hydrogen side, while the air side remains open. The thermal dynamic equations of the electric furnace and preheating device under unsteady-state conditions are described by the following equation:

In Eq. (22), Cf [J/(mol·K)] and Cph [J/(mol·K)] denote the equivalent capacities of the electric furnace and the preheating device, respectively. Tcand Tph are the temperatures of the electric furnace and the preheating device, respectively. Pph(kW) is the preheating power and Ppp(kW) is the pump power.

The inlet temperature change (Tin) equation of the SOEC electrolysis system can be expressed by Eq. (23), where denotes the equivalent heat capacity at the inlet of the stack.

Additionally, the variation in the stack temperature is affected by the change in the power supply and load power. Generally, a PID controller is configured in both the electric furnace and preheating device to regulate their respective power to achieve the expected stack temperature. Figure 14 depicts the thermal dynamic model of the electric furnace and preheating device considered in this analysis.

Adaptive time-varying LPV-MPC optimal control

In the SOEC hydrogen electrolysis system, the temperature of the stack is affected by various factors, among which the variation of the high temperature vapour and the electric heating power of the furnace play a major role, and their changes directly lead to changes in the temperature of the stack. The equation for the temperature change of the stack can be expressed as follows:

To achieve effective control of the temperature of the stack, the model is linearized and the linear parameter varying (LPV) model is used for predictive control modeling. LPV-MPC partially linearizes and processes offline to build a matching objective function, and then conducts research on linear variable parameter time-varying model predictive control methods. Finally, a linear state space model of the current temperature is obtained for the design and implementation of subsequent control strategies. The adaptive LPV-MPC thermal dynamic control system is shown in (Fig. 15), which integrates various types of information to achieve precise control of the stack temperature.

In the LPV-MPC model, the spatial variable involves the temperature distribution at different locations inside the stack. The temperature of the electric furnace, as an important device for providing heat, directly affects the overall heat input to the stack. The preheating device can preheat the material entering the stack, and its temperature state has an important influence on the initial thermal conditions of the stack. The temperature at the entrance of the stack reflects the thermal state of the material entering the stack at the moment of entry. The internal temperature of the stack, the electrical heating power, and the preheating power together constitute a state vector describing the thermal state of the stack system, and these variables are uniformly noted in the form in Eq. (25).

Based on the above state variables, the equation representing the temperature variation of the stack can be simplified as follows:

Due to the nonlinear characteristics of the stack temperature control systems, direct application of linear control methods may not be effective. Therefore, the local linearization method is adopted to approximate the nonlinear system as a linear system near a certain operating point. Specifically, at a certain operating point \((\mathop {r_{1} }\limits^{ - } ,\mathop {r_{2} }\limits^{ - } )\), a small disturbance \((\Delta r_{1} ,\Delta r_{2} )\) is added and the nonlinear equation describing the temperature change of the stack (Eq. (24)) is expanded by Taylor series to obtain a locally linearized equation (Eq. (27)). Linear control theory is applied near this operating point, greatly simplifying the design of the controller.

Further process the linearized model within the sampling period t. By using the system matrices \({\text{M}}_{{1}} (\mathop {r_{1} }\limits^{ - } ,\mathop {r_{2} }\limits^{ - } )\) and \({\text{M}}_{{2}} (\mathop {r_{1} }\limits^{ - } ,\mathop {r_{2} }\limits^{ - } )\), introducing the bias term \(\chi_{{\text{d}}} (\mathop {r_{1} }\limits^{ - } ,\mathop {r_{2} }\limits^{ - } )\) and discretizing it, the discretized state space equation (Eq. (28)) is obtained.

To obtain a practical MPC prediction model, it is necessary to process the variables \(I_{c}\) and V in the time domain of interest. Due to the different dimensions of these two variables, direct calculation and comparison may be difficult. Therefore, standardization is required to make their dimensions the same. After weighted summation and adaptive dynamic weight optimization strategy, the objective function (G) equation (Eq. (29)) is established.

In Eq. (29), β is the adaptive weight, which is positively correlated with the electrolysis current, and adjusts the weight of the current-related term in the objective function, so as to achieve the objective adjustment of the proportion of weight according to the change of electrolysis current. λ1 and λ2 depend on the weight coefficients of the influence of electrolysis factors on the model, which are used to balance the importance of different terms in the objective function. Ic,max and Vmax are the maximum values of electrolysis current intensity and material flow rate, respectively, which are used to normalise the variables and map different ranges of variables to the interval from 0 to 1 by dividing the variables by their maximum values, so as to uniformly measure the influence of different variables in the objective function.

To further improve the control performance, an adaptive optimisation strategy is used. This strategy integrates the prediction error of temperature (T) and the need for optimising the prediction time domain. By constructing the optimised prediction time domain equation (Eq. (30)), the length of the prediction time domain can be dynamically adjusted according to the actual situation of the system. When the prediction error is large, the prediction time domain is automatically reduced to improve the prediction accuracy and optimise the computation time length. Conversely, the prediction time domain is enlarged to take into account the electrolytic state of the system in an all-round way. This strategy enables the control system to better adapt to changes in the external environment and fluctuations in internal parameters.

In Eq. (30), \(T_{t}^{{\text{P}}}\) is the predicted value of temperature (T) at time t; \(T_{t}^{{\text{M}}}\) is the actual value of temperature (T) at time t. M is a function related to the temperature prediction error, and the prediction time domain \(N_{t}^{{\text{P}}}\) changes with M. \(H_{{t{\text{,max}}}}\) is the maximum objective function deviation, which is a pre-set threshold, when the objective function has a large prediction error, M becomes larger, and \(N_{t}^{{\text{P}}}\) becomes smaller, and in case of a large prediction error, the prediction time domain can be automatically reduced. which improves the prediction accuracy and optimises the computation time. On the contrary, the prediction time domain is enlarged and the electrolysis state of the system is considered comprehensively to improve the stability and reliability of control.

Safety constraints

To ensure the safety and stability of the SOEC stack system, in addition to capacity and ramp constraints for auxiliary systems such as pumps, heaters and preheaters, safety constraints for H2 concentration in the hydrogen inlet, material utilisation, electrolysis current and system temperature need to be analysed.

The H2 concentration constraint in the hydrogen side inlet can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (31), \(M_{{{\text{pp,H}}_{{2}} }}\) is the mass flow rate of the hydrogen pump in the inlet, \(M_{{{\text{pp,H}}_{{2}} {\text{O}}}}\) is the mass flow rate of the water vapour pump.

Water vapour is used as a feedstock for the electrolysis reaction, H2 in the inlet prevents oxidation of the electrodes and improves the efficiency of hydrogen production, and air in the inlet serves as a carrier in the generation of O2, which reduces the overpotential of the oxygen electrodes and maintains the temperature of the stack uniformly. Therefore, a safety constraint on the material utilisation in the stack system is required, which can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (32), \(Y_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} {\text{O}},\max }}\),\(Y_{{{\text{H}}_{{2}} ,\max }}\) and \(Y_{{{\text{O}}_{{2}} ,\max }}\) are the maximum utilisation of materials H20, H2 and O2 respectively.

The safety constraint on the electrolytic current aa can be expressed as follows:

Excessive rate of change of stack temperature at high temperatures also accelerates stack degradation, and gradient constraints and creeping constraints on the system temperature can be expressed as follows:

In Eq. (34), \(T_{{{\text{in}}}}\) is the inlet temperature of the stack; \(\nabla T_{\max }\) is the maximum allowable temperature gradient; \(T_{{{\text{d}},\max }}\) and \(T_{{{\text{u}},\max }}\) are the maximum rate of decrease and maximum rate of increase of the electrolysis temperature T, respectively; and \(T_{t - 1}\) and \(T_{t}\) are the electrolysis temperatures at the time of (t-1) and at the time of t, respectively.

Simulation analysis

To enhance the stack safety and service life, the whole stack must be evenly heated. When the electrolysis system operates in the temperature range of 790 ~ 810 ℃, measures such as adjusting the electrolytic current (Ic), steam flow rate, and electric furnace power, are taken to maintain a stable stack temperature during variable load operation. By comparing the advantages and disadvantages of PID control with adaptive dynamic weight linear variable parameter optimization model predictive control (abbreviated in this paper as Improved Model Predictive Control, I-MPC), the effectiveness of maximum hydrogen production point tracking on the improvement of hydrogen production rate is analyzed. This helps achieve the goal of dynamic load control. Table 614,16 lists the parameters of the SOEC high-temperature electrolysis system.

Variable load transition process

In this work, the PID and I-MPC control modes for variable load scenarios are simulated and analyzed using MATLAB software. In the analysis, the system load is stepped from 120 to 140 kW. Figure 16 presents the full response of the SOEC electrolysis system over a time span from 0 to 750 s as the load changes. The blue curve indicates the variation in SOEC parameters under PID control, while the red curve shows the corresponding variations under I-MPC control.

Both PID and I-MPC control modes can effectively track changes in grid load, with a total transition time of approximately 500 s. During this period, the electrolytic efficiency drops sharply, which is expected, as the electrolytic system absorbs surrounding energy to increase internal energy during the transient phase and while maintaining temperature. However, in terms of maintaining stack temperature stability and improving electrolysis efficiency, the I-MPC control mode outperforms the PID control mode, with a temperature difference in the stack of less than 1 ℃. As the electrolytic load increases, the current density rises, while water vapor, electrolytic voltage, and H2 flow rate decrease significantly.

To analyze the load change in SOEC electrolytic hydrogen production and compare the two control modes, the time scale is expanded to 60 s, as shown in (Fig. 17). It is noted that the electrolytic voltage, material flow rate, and electrolytic temperature inertia differ by several orders of magnitude in their response times. Overall, the system will undergo three stages of multi time scale dynamic behavior (millisecond, second, and minute) before transiting to a new steady state point. The three stages are described as follows:

Magnification of the first 60 s of SOEC operation under variable load. (a) Total load at the grid side. (b) Stack temperature. (c) Current density. (d) Vapor velocity. (e) H2 velocity. (f) Electric furnace power. (g) Single cell voltage. (h) Electrolytic efficiency. (i) Steam utilization. (j) Air flow rate.

Stage 1 (within 1 s): The electrolytic voltage quickly adjusts to accommodate the step change in the total electrolytic power of the system load, effectively tracking the load change during this stage.

Stage 2 (within a few seconds): The electrolytic voltage rapidly fluctuates to compensate for the unstable material flow rate, while the total electrolytic power is stable during this process. By the end of this stage, the electrolytic voltage has reached a quasi-steady state.

Stage 3 (within a few minutes): The electrolytic voltage adjusts more slowly to compensate for fluctuations in the electrolytic temperature, while the material flow rate reaches a quasi-steady state.

Finally, the electrolysis temperature stabilizes at a steady-state point, all control variables reach steady-state, and the electrolysis system completes the transition process, successfully tracking the maximum hydrogen production point.

Grid dispatching analysis

The simulation results obtained in this study confirm the feasibility of variable load operation of the SOEC electrolytic hydrogen generation system. The SOEC electrolytic hydrogen generation module is now incorporated into a distribution network in Xinjiang, China, functioning as a flexible load for grid dispatching. This integration allows for the assessment of the SOEC electrolytic hydrogen generation system’s ability to coordinate with power grid operations and effectively absorb renewable energy for power generation. It is noted here that the SOEC electrolytic hydrogen production system has completed 24 h of operation within the power grid dispatching process, with dispatching instructions updated hourly. Figure 18 illustrates the system’s operation under PID control mode and I-MPC control mode.

Figure 18 shows that during grid dispatching, both PID and I-MPC control modes can transition effectively to the current load operation point within each dispatching period. However, the stack temperature under I-MPC control is more stable than that under PID control, remaining close to the set target of 800 ℃ with fluctuations of no more than 0.5 ℃. It is also noted that in the transition process, the electrolysis efficiency in the I-MPC control mode improves more quickly than in the PID control, not only reaching the new steady-state point faster but also improving the overall electrolysis efficiency. At the same time, it is found that larger load changes require greater adjustments in current density to maintain the balance of the SOEC stack.

Conclusion

From the perspective of a 3D model of a single SOEC stack, this paper initially presents a comprehensive optimization method using the Adaptive Incremental Kriging surrogate model, modularizing the stack system. It then proposes an adaptive time-varying LPV-MPC optimization control method designed to ensure stack temperature stability. Based on the theoretical analysis and simulation experiments performed in this study, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

Compared to the lumped model, I-KSM provides a more accurate simulation and analysis of the operational dynamics of the SOEC stack, as well as the spatial characteristics of physical quantities such as electrolytic voltage, current density, stack temperature, and material concentration. This approach effectively reduces simulation time compared to 3D models. Additionally, the distribution in the stack affects the electrolytic current density, with the middle section of the stack exhibiting higher temperatures than the upper and lower sections, where the temperature of the upper section is the lowest. Under the same conditions, with the increase in the electrolytic voltage, the temperature of the stack will also increase.

-

(2)

The I-MPC control mode offers significant advantages over the PID control mode in maintaining temperature stability within the electrolytic hydrogen production modular system and improving the electrolysis efficiency. With the increase in the electrolytic load, the current density rises, while water vapor, electrolytic voltage, and H2 flow rate decrease significantly.

-

(3)

In the new energy grid dispatching scenario, the proposed optimal control method can effectively adjust the SOEC to the current load operation point for each dispatching period. It is particularly effective at stabilizing the stack temperature and enhancing electrolysis efficiency.

Although the I-KSM enhances computational efficiency for small-to-medium stacks, simulating ultra-large stacks poses unresolved challenges. As the variable count (e.g., temperature and gas concentration per cell) increases, the augmented space dimensionality may trigger the “curse of dimensionality”, diminishing the surrogate model’s predictive accuracy. Practical implementation in large-scale dynamic industrial environments necessitates addressing limitations such as sampling dependency, oversimplified physics, and scalability constraints. Future research should prioritize hybrid modeling (e.g., integrating physics-informed neural networks), adaptive online learning for real-time parameter updates, and embedded control strategies to bridge the gap between simulation and industrial deployment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chi, Y. et al. Fast and safe heating-up control of a planar solid oxide cell stack: A three-dimensional model-in-the-loop study. J. Power Sour. 560, 232655 (2023).

Fu, C., Lin, J., Song, Y., Li, J. & Song, J. Optimal operation of an integrated energy system incorporated with HCNG distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 11, 2141–2151 (2020).

Guo, M., Xiao, G., Wang, J.-Q. & Lin, Z. Parametric study of kW-class solid oxide fuel cell stacks fueled by hydrogen and methane with fully multiphysical coupling model. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 9488–9502 (2021).

Chi, Y. et al. Optimizing the homogeneity and efficiency of a solid oxide electrolysis cell based on multiphysics simulation and data-driven surrogate model. J. Power Sour. 562, 232760 (2023).

Wehrle, L., Schmider, D., Dailly, J., Banerjee, A. & Deutschmann, O. Benchmarking solid oxide electrolysis cell-stacks for industrial power-to-methane systems via hierarchical multi-scale modelling. Appl. Energy 317, 119143 (2022).

Rizvandi, O. B., Jensen, S. H. & Frandsen, H. L. A modeling study of lifetime and performance improvements of solid oxide fuel cell by reversed pulse operation. J. Power Sour. 523, 231048 (2022).

Shi, H. et al. On-line adaptive asynchronous parameter identification of lumped electrical characteristic model for vehicle lithium-ion battery considering multi-time scale effects. J. Power Sour. 517, 230725 (2022).

Chi, Y., Lin, J., Li, P. & Song, Y. Investigating the performance of a solid oxide electrolyzer multi-stack module with a multiphysics homogenized model. J. Power Sour. 594, 234019 (2024).

Motylinski, K., Kupecki, J., Numan, B., Hajimolana, Y. S. & Venkataraman, V. Dynamic modelling of reversible solid oxide cells for grid stabilization applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 228, 113674 (2021).

Wang, C., Chen, M., Liu, M. & Yan, J. Dynamic modeling and parameter analysis study on reversible solid oxide cells during mode switching transient processes. Appl. Energy 263, 114601 (2020).

Korkut, E. H. & Surer, E. Visualization in virtual reality: A systematic review. Virtual Real. 27, 1447–1480 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Robust control of RSOC/Li-ion battery hybrid system based on modeling and active disturbance rejection technology. Atmosphere 14, 947 (2023).

Huang, D. et al. A multiphysics model of the compactly-assembled industrial alkaline water electrolysis cell. Appl. Energy 314, 118987 (2022).

Xing, X., Lin, J., Brandon, N., Banerjee, A. & Song, Y. Time-varying model predictive control of a reversible-SOC energy-storage plant based on the linear parameter-varying method. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 11, 1589–1600 (2019).

Li, Z., Zhang, H., Xu, H. & Xuan, J. Advancing the multiscale understanding on solid oxide electrolysis cells via modelling approaches: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 141, 110863 (2021).

Xing, X., Lin, J., Song, Y. & Hu, Q. Maximum production point tracking of a high-temperature power-to-gas system: A dynamic-model-based study. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 11, 361–370 (2019).

Botta, G., Romeo, M., Fernandes, A., Trabucchi, S. & Aravind, P. V. Dynamic modeling of reversible solid oxide cell stack and control strategy development. Energy Convers. Manag. 185, 636–653 (2019).

Xing, X., Lin, J., Song, Y., Song, J. & Mu, S. Intermodule management within a large-capacity high-temperature power-to-hydrogen plant. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 35, 1432–1442 (2020).

Zhang, D., Bertei, A., Tariq, F., Brandon, N. & Cai, Q. Progress in 3D electrode microstructure modelling for fuel cells and batteries: transport and electrochemical performance. Prog. Energy 1, 012003 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Numerical investigation of solid oxide electrolysis cells for hydrogen production applied with different continuity expressions. Energy Convers. Manag. 149, 646–659 (2017).

El Jery, A., Salman, H. M., Al-Khafaji, R. M., Nassar, M. F. & Sillanpää, M. Thermodynamics investigation and artificial neural network prediction of energy, exergy, and hydrogen production from a solar thermochemical plant using a polymer membrane electrolyzer. Molecules 28, 2649 (2023).

Wehrle, L. et al. Optimizing solid oxide fuel cell performance to re-evaluate its role in the mobility sector. ACS Environ. Au 2, 42–64 (2021).

Min, G., Choi, S. & Hong, J. A review of solid oxide steam-electrolysis cell systems: Thermodynamics and thermal integration. Appl. Energy 328, 120145 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Three-dimensional modeling of flow field optimization for co-electrolysis solid oxide electrolysis cell. Appl. Therm. Eng. 172, 114959 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Thermal performance analysis of an integrated solar reactor using solid oxide electrolysis cells (SOEC) for hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 264, 115762 (2022).

Kamkeng, A. D. N. & Wang, M. Long-term performance prediction of solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC) for CO2/H2O co-electrolysis considering structural degradation through modelling and simulation. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 132158 (2022).

Pourrahmani, H., Xu, C. & Van Herle, J. The thermodynamic and life-cycle assessments of a novel charging station for electric vehicles in dynamic and steady-state conditions. Sci. Rep. 13, 11159 (2023).

Mendoza-Hernandez, O. S. et al. Exergy valorization of a water electrolyzer and CO2 hydrogenation tandem system for hydrogen and methane production. Sci. Rep. 9, 6470 (2019).

Navasa, M., Miao, X. Y. & Frandsen, H. L. A fully-homogenized multiphysics model for a reversible solid oxide cell stack. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 44, 23330–23347 (2019).

Ba, L. et al. A novel multi-physics and multi-dimensional model for solid oxide fuel cell stacks based on alternative mapping of BP neural networks. J. Power Sour. 500, 229784 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Approval Number: 52267005&52067020)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. W.W.: Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. Y. C.: Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Software Supervision. J. L.: Methodology, Investigation. X. Z.& B. L.: Investigation. Y. W.: Experimentation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Wang, W., Chi, Y. et al. Modeling and optimization control of SOEC with flexible adjustment capabilities. Sci Rep 15, 22020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05359-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05359-5