Abstract

This study investigates the use of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) with the Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) process to fabricate high-quality cylindrical components from ER308L stainless steel. The primary objectives are to assess the mechanical properties—such as tensile strength, impact resistance, and hardness—while also exploring the metallurgical characteristics, including microstructure and grain size across different sections of the components. A detailed microstructural analysis reveals the uniformity and integrity of the components, with findings indicating a clear link between microstructural features and mechanical performance. Advanced characterization techniques, including optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy, are employed to study the microstructure and failure mechanisms of the samples. The WAAM-CMT method produces components with high density and minimal defects, making them well-suited for a range of industrial applications, including cylindrical shells or housings in the marine and defense sectors, pressure vessels, and heat exchangers that require corrosion-resistant, high-strength materials. Additionally, the research highlights the cost-effectiveness and time-efficiency of WAAM, positioning it as a practical alternative for large-scale manufacturing in response to the growing demand for innovative production techniques. Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the potential of WAAM to address challenges in modern industry and contributes to advancing additive manufacturing technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wire arc addictive manufacturing or simply WAAM is a well-defined addictive manufacturing technology, which has a great application in the current scenario. A shift has occurred in the ability to manufacture structurally complex components with unrivalled design flexibility1,2,3,4,5. Each additive manufacturing process differs significantly in terms of heat generation, tool movement, deposition techniques, and material feed mechanisms, which opens the door for tailored applications depending on the specific needs of a component or project. In the case of WAAM, the technology falls under the category of Direct Energy Deposition (DED), which includes both wire-feed and powder-feed systems. However, among these, the wire-feed approach is particularly advantageous due to its higher material utilization, lower operating cost, and reduced complexity in handling feedstock materials1,6,7,8,9.

Compared to traditional powder metallurgy-based AM processes, WAAM offers a significantly lower cost per kilogram of deposited material and results in minimal raw material loss, making it a sustainable and economical option. The WAAM process is particularly well-suited for producing medium to large-sized components at a relatively fast rate. It is capable of fabricating three-dimensional metallic structures with high structural integrity using standard welding equipment. In this process, an electric arc is employed to melt the wire feedstock, which is directly deposited layer by layer onto a substrate to build the desired component shape. Because the full volume of wire fed into the torch is used in the part being constructed, the method boasts nearly 100% material utilization, meaning there is negligible to no waste of feed material10,11,12,13,14. This high efficiency, in terms of material input versus output, enhances the overall sustainability of the process. WAAM systems typically achieve deposition rates ranging between 10 and 15 kg/h, making them one of the fastest AM methods for metal deposition. This high deposition rate, coupled with the relatively low cost of raw materials and basic equipment requirements, enables WAAM to manufacture large metal parts at a fraction of the cost associated with other AM technologies9,15,16,17,18. The standard setup for a WAAM system includes a welding power source, a wire feed mechanism, and a torch, all of which can be mounted on motion systems such as robotic arms or CNC-controlled gantries to ensure precise path control and deposition accuracy. Since the feedstock is a consumable electrode, it not only serves as the material input but also plays a role in sustaining the arc during the deposition process, thereby integrating material delivery with energy application19,20,21,22,23,24. This dual functionality enhances the process efficiency and further solidifies WAAM’s standing as a leading technique for high-volume, large-scale metal additive manufacturing.

Shanthar et al.25 identified three main AM methods: inkjet printing, powder-bed metal technology (PBT), and blown powder/wire technology. The most developed techniques use electron beam and laser melting. WAAM utilizes metal wire as filler, forming layers with an electric arc under 3D CAD guidance. Dalpadula et al.26 found WAAM more economical than PBT, reducing costs by 80% and energy use by 90%. With a deposition rate of 160 g/min, WAAM is faster than PBT’s 12 g/min. However, WAAM’s design limitations restrict certain geometries, spurring research into parameter optimization. Tomar et al.27 indicated minimal research on microstructural faults in WAAM and their impact on material properties. Impurities and faults like porosity and hot cracks can weaken corrosion resistance and cause fatigue failures. Li et al.28 noted MIG’s efficiency due to the wire aligning with the welding flame, easing tool path planning. CMT, a MIG variant, produces high-quality beads with minimal spatter. However, challenges like arc wandering complicate titanium deposition, making plasma arc or TIG preferable. Gurmesa et al.29 observed that high heating rates in AM create residual stresses, causing product distortion post-unclamping. Preventative measures include symmetric construction and alternating layer deposits on both sides to balance stress. Li et al.30 investigated the mechanisms behind defect formation in WAAM, such as wire droppage, arc light fluctuations, molten pool oscillation, and wire jamming. By analysing video data for identifying these anomalies in real-time, enhancing the quality and reliability of the additive manufacturing process. The approach leverages unsupervised learning methods, which do not require labelled datasets, making them suitable for real-time applications where labelled data may be scarce or unavailable. Espera et al.31 demonstrated the advanced capabilities of additive manufacturing (AM) in fabricating interdependent components simultaneously on a single substrate without incorporating the starting plate as a permanent part of the final product. This approach is particularly useful in designs that incorporate symmetrical features, as it minimizes thermal distortion and reduces the size of heat-affected zones (HAZ). Such techniques enhance structural precision and allow greater design flexibility, especially for complex aerospace components such as wing spars, which require both lightweight construction and high strength. By reducing the need for external support structures, this method streamlines the production process and reduces post-processing requirements.

Diegel et al.32 further expanded on the relationship between deposition strategies and structural quality, reporting that reducing layer heights leads to shorter tool paths, which in turn helps to decrease residual stresses. These stresses, if unaddressed, can compromise dimensional accuracy and lead to warping or distortion in the final product. Additionally, by harnessing the surface tension characteristics of molten metal during deposition, it is possible to create horizontal or slightly overhanging features without additional support material. This self-supporting behavior is beneficial for minimizing material waste and improving geometric freedom. Fine-tuning process parameters such as travel speed (TS), wire feed rate, and energy input can significantly influence build quality, further reducing distortion and improving surface finish. Zhao et al.33 investigated the thermal behavior in both single-pass and multilayer welds and found that when consecutive layers are deposited in the same direction, a higher temperature gradient develops. This increased gradient can lead to uneven heat distribution, potentially causing defects or irregularities. Their findings suggest that alternating the deposition direction between layers may lead to more effective heat dissipation and structural uniformity. Suryakumar et al.34 evaluated the mechanical properties of metallic parts fabricated using WAAM, particularly hardness and tensile strength. They discovered that while hardness varied across the height of the component due to thermal cycling effects, tensile stress remained consistently distributed along horizontal planes. High Localized Melting (HLM) proved effective in enhancing interlayer bond strength, influenced significantly by controlled interlayer temperatures.

Xiong et al.35 identified key factors affecting surface quality in Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW)-based AM processes, such as interlayer temperature, wire feed speed, and travel speed. Elevated interlayer temperatures were found to increase surface roughness and reduce the height of each deposited layer. Finally, Sadhya et al.36 demonstrated that introducing low-power pulsed laser assistance into MIG-based AM significantly minimized bead width variation and improved material utilization by approximately 15%. Through tests using lasers from 0 to 600 watts, they observed considerable surface quality enhancements in aluminum alloy components, making this technique promising for high-performance manufacturing applications.

While much of the existing research on Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) has focused on the properties and behavior of materials such as mild steel, carbon steel, and aluminum alloys, there remains a significant need to explore the mechanical and metallurgical characteristics of ER308L stainless steel, particularly in components fabricated through the WAAM process. ER308L stainless steel is commonly used in industries requiring high-strength and corrosion-resistant materials, yet its performance when produced via additive manufacturing methods like WAAM remains underexplored. This study aims to address this gap by thoroughly investigating the mechanical and metallurgical properties of WAAM-fabricated ER308L components. As WAAM with Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) continues to gain traction in industrial applications worldwide, the importance of understanding the behavior of materials like ER308L stainless steel in this context becomes increasingly apparent. This growing interest is supported by feedback from researchers at leading institutions in the field of additive manufacturing, who emphasize the promising potential of the WAAM-CMT method for producing complex, high-performance components. However, despite this enthusiasm, there is still limited knowledge regarding the microstructural transformations that occur along the build direction in WAAM-processed stainless steel, which is critical for understanding the relationship between material structure and performance.

Furthermore, there is a clear need for continued research to optimize welding process parameters, which play a key role in determining the mechanical properties and overall quality of the final components. A comprehensive evaluation of these factors is essential to fully assess the performance characteristics of WAAM-fabricated ER308L stainless steel components. This study is aimed at filling these crucial knowledge gaps, providing valuable insights into the potential of WAAM for manufacturing high-quality, reliable ER308L stainless steel components, and advancing its application across various industrial sectors where performance and material integrity are paramount.

This experimental study aims to accomplish several key objectives: firstly, to evaluate the mechanical properties—including tensile strength, impact resistance, and hardness—of cylindrical stainless steel (ER308L) components fabricated using the Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing with Cold Metal Transfer (WAAM-CMT) process. Secondly, it seeks to investigate the metallurgical characteristics of these components by examining microstructure and grain size across different regions, specifically comparing the top and bottom sections. A core focus of the research is to establish correlations between the microstructural features and the resulting mechanical behavior. Furthermore, the study explores the thermal effects influencing microstructure evolution within the stainless steel during the additive process, thereby offering insights into the material’s performance and long-term durability. The overarching goal is to conduct a layer-specific comparison of mechanical and microstructural properties along the vertical build direction, with emphasis on linking variations in grain size, hardness, and ductility between the upper and lower regions of the cylindrical component.

Materials

The initial phase of this analysis involves a comprehensive evaluation of the properties of the ER308L stainless steel filler wire. Following this, a well-structured process cycle must be established to enable efficient and cost-effective production of the component. Selecting optimal parameters for the printing process is critical to minimizing defects and reducing production costs. To achieve this, parameter optimization was conducted on a sample wafer plate by adjusting the weld speed and current (I) using a Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) machine. In this study, ER308L stainless steel filler wire with a diameter of 1.2 mm was utilized. Tables 1 and 2 showed the chemical composition and mechanical properties of the filler wire, respectively, providing foundational data for the process optimization. The straight cylindrical stainless-steel component was fabricated using the Fronius CMT Advanced 4000 VR welding system. The ER308L filler wire utilized in this process has a chemical composition detailed in Table 2. The mechanical properties of the ER308L filler wire include a yield strength of 0.2% (MPa), maximum tensile strength (MPa), elongation over a 50 mm gauge length (percentage), and impact toughness at room temperature. These parameters are critical for assessing the material’s suitability in applications requiring robust mechanical performance and resilience.

Parameter optimization

The initial phase of the welding process involves the precise optimization of Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) Arc Welding parameters. Five primary parameters are instrumental in controlling the welding quality and ensuring a stable welding process. These parameters include wire feed speed (m/min), average voltage (V), average current (A), travel speed (mm/min), and the shielding gas composition (85% Argon and 15% CO₂ at flow rate lpm). Optimization was achieved by systematically varying these parameters and analyzing the resulting welding beads to assess their impact. A trial-and-error experimental approach was used to optimize the parameters. Various combinations of wire feed speed, voltage, current, and weld speed were tested. Throughout the experiment, the wire feed rate and arc length correction factor were held constant. For enhanced accuracy, the arc length correction was set to zero. The detailed results and optimized parameter configurations are presented in Table 3, summarizing the findings of the optimization experiment. Based on the experimental results, we have determined the optimal parameter settings as follows: a wire feed speed of 5 m per minute, a current of 130 amperes, a voltage of 14.3 V, and a shielding gas composition of 85% Argon and 15% CO₂ at a flow rate of 15 L per minute. These optimized values are presented in Table 4.

Fabrication technique

Through the synergistic control of the Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) system, the power source is capable of operating in multiple advanced modes. In synergic control CMT (Cold Metal Transfer) process parameters such as wire feed speed, welding current, voltage and arc length are automatically regulated to maintain optimal arc stability and weld quality. These include Constant Current Cold Metal Transfer (CC-CMT), standard Cold Metal Transfer (CMT), Pulsed Cold Metal Transfer (PCMT), Advanced Cold Metal Transfer (ADV-CMT), and Advanced Pulsed Cold Metal Transfer (ADV-PCMT). Each mode provides specific benefits, enhancing control over welding processes and optimizing results for various applications. Figure 1, presents an image of the CMT welding machine configured for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM), showcasing its setup and integration for advanced fabrication and Fig. 2 shows the schematic path planning strategy for the cylindrical deposition.

The stainless steel (ER308L) straight cylindrical component was fabricated using advanced Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) technology. In this setup, the welding gun was held stationary, while a rotating table facilitated the substrate’s movement, enabling precise layer-by-layer deposition of molten metal. A controlled 15 mm standoff distance was maintained between the nozzle and the substrate to ensure consistent deposition quality. Shielding gas was employed throughout the process to minimize welding defects such as porosity and variations in metal transfer mode, enhancing the overall integrity of the component. In the WAAM setup, although the substrate rotates on a fixed table, the welding torch itself has Z-motion capability. After the completion of each layer, the torch height was manually adjusted upward by a fixed increment to accommodate the next layer. This manual adjustment ensured consistent standoff distance and proper deposition geometry throughout the build process.

After each layer was applied, a 120-s dwell period was introduced, allowing adequate cooling of the previous layer and helping to control thermal stresses and structural stability. Implementing a dwell period of approximately 120 s, can effectively reduce the interpass temperature to below 100 °C. The torch was raised by 2.5 mm after each layer, matching the average layer height. This value was determined based on experimental observation to ensure adequate fusion between layers, minimized distortion or collapse and sufficient cooling time (120 s) before the next layer was added. The final component, illustrated in Fig. 3, achieved a height of 160 mm, a diameter of 100 mm, and a uniform wall thickness of 7.5 mm. Figure 3 presents different perspectives of the component, including (a) a side view, (b) a top view, and (c) a close-up of the wall thickness. With an average layer height of 2.5 mm, the component was built incrementally across 64 layers, each layer incorporating the 120-s cooling interval to ensure optimal layer adhesion and overall component quality.

To remove the substrate from the component, abrasive cutting was applied, ensuring precise separation. The component then underwent machining on a CNC lathe, where 1.75 mm was removed from both the exterior and interior surfaces. A coolant system was employed throughout this process to maintain optimal machine temperature and prevent overheating during rotation. Feed rate and spindle speed was maintained at ~ 0.15 mm/rev and ~ 300 rpm respectively. The component was subsequently divided into two sections: the top and bottom portions, as illustrated in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3, (d) presents a side view of both sections after separation, (e) provides a top view of the machined component, and (f) highlights a consistent wall thickness of 4 mm for each portion.

Sample preparation

Tensile properties were evaluated using a universal testing machine, following ASTM E8M standards (refer to Fig. 4). Specimens were loaded at a rate of 1.5 kN/min as per ASTM guidelines. Three tensile samples were prepared from each section (top and bottom) of the component to assess tensile properties. Smooth tensile specimens, designed in accordance with the ASTM E8M subsize standard, were extracted with a length of 75 mm, gripper width of 10 mm, gauge width of 6 mm, and gauge length of 25 mm (see Fig. 4a). Additionally, Fig. 4 illustrates notch tensile specimens with a 75 mm length, 10 mm width, and a 45° notch with a 2 mm depth.

To assess component hardness, measurements were conducted using a Matzusawa MMT-X7 Vickers microhardness testing machine, with a load of 0.5 kg applied for a 10-s dwell time and 1 mm spacing between each measured point. A thorough hardness survey was carried out along the building direction, from the substrate through to the end of the component. The extraction points for tensile and impact specimens from both the top and bottom sections are illustrated in Fig. 5. The figure shows detailed images of the extraction and dimensions of each specimen: (a) smooth-surface tensile specimen, (b) specimen extraction depiction from the component, (c) notched tensile specimen, and (d) impact hardness specimen.

Figure 5 illustrates various testing machines and devices utilized in material evaluation: (a) Universal Testing Machine, (b) Charpy Impact Testing Machine, (c) Microhardness Measurement Machine, (d) Optical Microscope and (e) Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), which employs electrons for high-resolution imaging.

In the context of assessing impact toughness, a pendulum impact testing machine was employed to conduct the Charpy impact test, as shown in Fig. 5. This test involved three impact samples, all extracted from the same section of the component, ensuring consistency in the evaluation of material performance. The Charpy impact specimens were meticulously prepared according to the ASTM A370 subsize standard, featuring dimensions of 55 mm in length, a notch angle of 45°, and a notch depth of 2 mm. This standardized approach is crucial for accurately determining the impact toughness of both the top and bottom portions of the material under investigation.

Metallographic specimens were extracted from these regions and characterized using optical microscopy (OM) with a Huvitz microscope (Korea; Model: MIL-7100). To reveal the microstructure, the specimens underwent a polishing process using diamond paste, followed by etching with a 2% nital solution. Optical microscopy was then employed to examine the top and bottom portions of the specimens.

Additionally, the cracked surfaces of the specimens were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at both lower and higher magnifications. This SEM analysis focused on the fracture surfaces of the tensile and impact testing specimens, enabling a thorough examination to ascertain the mode of failure. The primary objective of this analysis was to determine whether the observed failures were brittle or ductile in nature, thereby providing critical insights into the material’s performance and behavior under stress.

After the construction of cylindrical component, it is machined into required dimensions. Then the mechanical and surface analysis were done on the product. Surface analysis including micro analysis which means normal dimension analysis and micro analysis including SEM and optical microscopy were done on it. The result of this tests is discussed below. The dimension of the standard fabricated cylinder after the printing is shown in the Table 5.

Results and discussion

Tensile properties

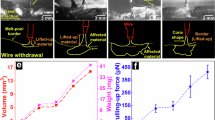

The tensile samples that were obtained from both the top and bottom sections are shown in Fig. 6. Panel (a) displays the samples before they were tested, and panel (b) displays the samples after they have been tested. In a similar manner, Fig. 7 illustrates a notch tensile sample, with panel (a) illustrating the condition before to testing in both areas and panel (b) displaying the samples after testing. In addition, the Charpy specimen is shown in Fig. 8 both before and after it was subjected to the impact test. According to the average values of ultimate tensile strength (UTS) for the top and bottom samples, the wall that was built using additive manufacturing demonstrates virtually similar UTS in both orientations. The top section measured 542 MPa, while the bottom portion measured 529 MPa. Based on this discovery, it seems that the material exhibits isotropic tensile properties. Recent research has found similar findings regarding the isotropic tensile strengths of ferrous components that were manufactured using wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM). It is important to note that the top section displays a much larger elongation in comparison to the bottom region. This may be ascribed to a transition from a ductile to a brittle behavior. The results of Table 6 demonstrate that the notch tensile strength is equivalent between the top and bottom parts of the structure. On the other hand, it is essential to take into consideration the fact that the tensile strength and hardness of the bottom zone are much greater than those of the top region2,8. Specifically, the disparities in microstructural characteristics that exist between the two locations are the primary cause of this divergence. In order to offer a more comprehensive illustration of these results, Fig. 9 presents a graphicald depiction of the tensile strength and elongation study.

Microhardness

The microhardness measurements that were taken on average for both the bottom and top areas are shown in Table 7. The data clearly indicate that the microhardness in the bottom section is noticeably higher than that observed in the top region. This significant difference in hardness values suggests a variation in the thermal history experienced by different sections during the fabrication process. Specifically, the elevated microhardness in the bottom region can be attributed to microstructural changes that are induced by the relatively higher heating and cooling rates encountered in that area during material deposition8. These rapid thermal cycles can lead to the formation of finer grain structures or phase transformations, which contribute to increased hardness. Additionally, the bottom region, being closer to the substrate, may experience more effective heat dissipation, influencing the cooling rate and subsequent microstructure. As a result of the accelerated heating and cooling process, this region is more susceptible to transitioning from a ductile to a brittle microstructural state, potentially impacting mechanical performance14,26. To gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of these variations, a detailed Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis of the cross-sectional slice will be conducted. This investigation will help identify specific microstructural features such as grain size, phase distribution, and possible formation of hard or brittle phases that could explain the differences in hardness. Such insights are essential for optimizing processing parameters and ensuring uniform mechanical properties throughout the component.

Impact toughness

The Charpy impact analysis is a vital method used to evaluate the impact toughness of materials, offering essential insights into their behavior and durability under conditions of sudden or dynamic loading. This analysis is particularly important for applications where materials may experience unexpected impacts, shocks, or abrupt stress. As shown in Fig. 8, the Charpy specimen is illustrated both before and after undergoing the impact test, providing a visual representation of the fracture behavior. The results of the test reveal the average impact toughness values for the Cold Metal Transfer with Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (CMT-WAAM) component. These values were determined to be approximately comparable to those of the filler wire utilized in the additive manufacturing process, suggesting that the additive process did not significantly deteriorate the toughness properties of the material. The detailed impact toughness values are presented in Table 8 for reference and comparison. Interestingly, the difference in impact toughness between the as-built WAAM component and the original filler wire was found to be minimal, indicating effective preservation of toughness characteristics during deposition. However, a slight reduction in toughness was noted in the lower region of the specimen. This reduction is likely due to the presence of residual ferrite, which leads to microstructural inconsistencies and the formation of weak zones1. These zones serve as initiation points for microcracks, ultimately reducing the material’s ability to absorb impact energy. Additionally, the hindrance of dislocation movement within the microstructure over short distances contributes to increased hardness but simultaneously causes a decrease in impact toughness, as previously mentioned in the microhardness analysis14. Figure 10 provides a graphical illustration of the microhardness variation, reinforcing the correlation between hardness and impact strength, and offering a more complete understanding of the mechanical behavior of the material across different regions.

Microstructural evaluation

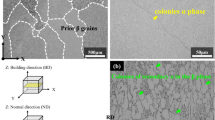

The microstructural samples were extracted from together the top and bottom sections of the component. Etched micrographs discovered coarse grains in the bottom (Fig. 11a) and fine grains in the top (Fig. 11b), importance the thermal gradient-induced microstructural modifications. The microstructure of the top and bottom sections were exposed by etching the specimens with a 2% Nital reagent. The microstructural analysis of the Wire Arc Additive Manufactured (WAAM) component reveals a heterogeneous grain structure characterized by both coarse and fine grains across different regions. Specifically, the coarse grains are predominantly composed of δ-ferrite (delta ferrite), while the fine grains primarily consist of γ-austenite (gamma austenite). This dual-phase microstructure arises due to the complex thermal cycles inherent in the WAAM process, which involve rapid heating and cooling, leading to non-equilibrium solidification conditions. In austenitic stainless steels, the presence of δ-ferrite is crucial for mitigating hot cracking during solidification6. However, excessive δ-ferrite can lead to embrittlement over time, especially when exposed to elevated temperatures, due to the formation of brittle intermetallic phases such as sigma phase. The proportion and morphology of δ-ferrite can vary throughout the build, influenced by factors like cooling rates and thermal gradients. For instance, studies have shown that the volume content of ferrite can increase with distance from the substrate, with different morphologies observed in various regions: lathy and granular ferrite in the bottom layers, skeletal ferrite in the top region, and a mix of morphologies in the middle part of the billet9.

The γ-austenite phase, stabilized by elements like nickel, is non-magnetic and offers excellent formability and corrosion resistance, making it ideal for various industrial applications. The distribution and stability of γ-austenite are essential for the mechanical performance of the component. The observed variation in grain structures and phase distribution across different regions of the WAAM component indicates anisotropic behavior. This anisotropy can manifest in mechanical properties, such as strength and ductility, varying with orientation. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the microstructural evolution, including the roles of δ-ferrite and γ-austenite, is vital for predicting and optimizing the performance of WAAM-fabricated components26.

Detailed observations of the microstructure were made across various locations on both the top and bottom parts of the component. Notably, consistent microstructural characteristics were identified across all samples of the Cold Metal Transfer with Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (CMT-WAAM), revealing no significant differences among them. Figure 12 displays comprehensive optical microstructures of the top region, though Fig. 13 depicts the bottom region. These images authorize the presence of finer grains at the bottom (Fig. 13c) and moderately coarser grains at the top (Fig. 12b), assistant the thermal analysis. Figure 12a displays a low-magnification optical micrograph of the top region of the WAAM-fabricated component. The microstructure discloses relatively coarse grains, representing slower cooling rates and prolonged thermal exposure caused by heat accumulation near the upper layers all through deposition. This is steady with the observed grain growth associated with higher interpass temperatures and reduced thermal gradients in the upper section of the build. Figure 12b offerings the same region at a higher magnification. Here, the γ-austenite matrix is clearly visible, along with isolated δ-ferrite phase formations. The morphology of δ-ferrite acts skeletal or vermicular, a common indicator of high heat input and extended solidification times. The coarse, elongated grains and reduced grain boundary density in this region suggest lower dislocation density, potentially leading to reduced hardness and higher ductility, as confirmed by the mechanical test results.

Figure 13a exhibitions a low-magnification vision of the bottom region. The microstructure lies of finer, more equiaxed grains, which consequence from the rapid heat extraction by the underlying substrate. This promotes a faster cooling rate and limits grain growth during solidification. The finer grains in this region are related with higher microhardness values owing to increased grain boundary area and higher dislocation density. Figure 13b deals a medium-magnification image where lathy δ-ferrite structures can be distinguished inside the finer austenitic matrix. These ferrite structures likely act as barriers to crack propagation and contribute to improved tensile strength, mainly under dynamic loading situations. Figure 13c, at higher magnification, discloses a more refined grain structure through a dense network of grain boundaries. The uniformity and tight spacing among grains in this image underscore the operational heat dissipation and controlled solidification attained in the initial layers. Such microstructures are valuable for applications demanding high strength and wear resistance.

The reheating effect reasons thermal cycling in the previously solidified layers. In the bottom region, early-deposited layers involvement multiple reheating cycles caused by subsequent layer accompaniments. These cycles indorse grain refinement through recrystallization and hinder grain growth, resulting in finer microstructures, as shown in Fig. 13c. This is consistent with the witnessed higher hardness and tensile power in the bottom region. On the other hand, in the top region, there are less reheating cycles and less thermal history, permitting grains to coarsen, as noticeable in Fig. 12b. The reduced remelting at the top contributes to larger grain size, lower dislocation density, and thus reduced hardness but upper ductility. Moreover, remelting at the boundary between layers enhances interlayer bonding, however excessive remelting can flat grain boundaries and reduce hardness. Therefore, controlling the energy input per layer, cooling time (120 s dwell), and layer height is necessary for achieving the preferred mechanical properties.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that the primary influence of heat input is observed in the grain size across different positions of the manufactured samples. For instance, the sample produced with the highest heat input in the top area exhibited an average grain size of 13.30 µm × 1.76 µm, while the sample fabricated with the lowest heat input in the bottom region demonstrated an average grain size of 11.2 µm × 1.68 µm. This variation can be attributed to the increased solidification time and reduced cooling rate associated with higher heat input, leading to the formation of coarser grains within the microstructures. The microstructural analysis of the material, derived from the two sections of the CMT-WAAM component, highlights the typical characteristics of both the top and bottom region samples, underscoring the overall uniformity and structural integrity of the fabricated component9.

Fracture surfaces

The fracture surface analysis of Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) cylindrical component specimens reveals distinct features at low magnification, including a fibrous area and shear lip fraction at the borders. In higher-magnification images, the central portion displays equiaxed dimples, predominantly surrounding larger dimples, with tearing ridges observed in the lower section. The dimples at the edges exhibit a parabolic shape and elongated characteristics, suggesting that shearing occurs in these regions. A similar fracture surface morphology is noted in the Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) of stainless steel. The predominance of dimpled features indicates a ductile failure mode in the upper section of the cylindrical component. Furthermore, the high-magnification fractographic analysis of the WAAM-fabricated component reveals distinct features indicative of ductile fracture mechanisms across different regions. In the central region, a network of rippling ridges interspersed with equiaxed dimples is observed. These equiaxed dimples are characteristic of tensile overload failure, resulting from microvoid coalescence under uniaxial tensile stress, where voids nucleate, grow, and coalesce to form a ductile fracture surface20. In contrast, the detailed image in Fig. 14, taken closer to the margin, shows elongated parabolic dimples. These features suggest the presence of shear stresses during fracture, as elongated dimples are typically associated with shear-dominated failure modes. The orientation and shape of these dimples provide insights into the direction and nature of the applied stresses during failure. Notably, the edges of the upper region’s specimen exhibit broader and longer dimples compared to those in the lower region. This observation correlates with the greater elongation observed in the upper specimen, indicating that the material in this region underwent more significant plastic deformation before fracture. The increased plasticity results in more pronounced shear forces at the edges, contributing to the formation of larger dimples and highlighting the ductile nature of the failure21,28. These fractographic features underscore the ductile failure mode across the component, with variations in dimple morphology reflecting differences in local stress states and deformation behaviors. Such detailed analysis is crucial for understanding the mechanical performance and failure mechanisms of additively manufactured components.

Conclusions

This project presents a detailed assessment of recent technological developments in the Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) process, with a particular focus on the Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) variant. The analysis encompasses multiple key aspects, including microstructural evolution, mechanical performance, common process-related defects, and the influence of post-processing treatments. The following conclusions were derived from this investigation:

-

a.

The CMT-based WAAM process enables the fabrication of stainless steel components with excellent density and structural reliability. These components, capable of forming both thin and thick walls, are generally free of major defects such as fractures or lack of fusion between layers, even across diverse and complex geometries.

-

b.

Microscopic examinations reveal smooth transitions and well-fused layers throughout the deposited structure. Weld beads exhibit uniformity with no visual evidence of cracks or bonding failures. However, it is observed that while microstructural features remain relatively stable, the dimensional accuracy and wall stability are sensitive to variations in heat input during deposition.

-

c.

The fabricated cylindrical walls show clear microstructural differences between the top and bottom regions. This gradient directly influences the hardness distribution, highlighting a spatial variation along the vertical build direction.

-

d.

Specifically, the bottom region exhibits higher hardness than the top, suggesting a directional dependence of mechanical properties. This anisotropy, likely resulting from thermal gradients and solidification dynamics, is reflected in differences in tensile strength, including both yield strength (NTS) and ultimate tensile strength (UTS).

-

e.

The mechanical performance of the CMT-produced components aligns closely with the baseline properties of ER308L stainless steel, confirming the process’s ability to preserve material characteristics while offering geometric flexibility.

-

f.

Due to their high density, corrosion resistance, and low defect rates, WAAM-CMT components are ideal for marine, defense, and pressure-related applications.

-

g.

Despite growing global interest, further research is needed to fully understand vertical microstructural changes and to optimize processing parameters for consistent performance.

Data availability

The data will be available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Cao, W. et al. Ultrahigh Charpy impact toughness (~ 450J) achieved in high strength ferrite/martensite laminated steels. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 1–8 (2017).

Prabhakaran, B., Sivaraj, P., Malarvizhi, S. & Balasubramanian, V. Mechanical and metallurgical characteristics of wire-arc additive manufactured HSLA steel component using cold metal transfer technique. Addit. Manuf. Front. 3(4), 200169 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Equilibrium phase diagram design and structural optimization of SAC/Sn-Pb composite structure solder joint for preferable stress distribution. Mater. Charact. 206, 113389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2023.113389 (2023).

Ni, Z. L. et al. Simulation of ultrasonic welding of Cu/Cu joints with an interlayer of Cu nanoparticles. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 109330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.109330 (2024).

Levitz, S. M. (1999). Cryptococcus neoformans by Casadevall, Arturo & Perfect, John R. (1998) ASM Press, Washington, DC. Hardcover. vol. 542 89.95. (ASMMemberprice: 79.95).

Wang, Z. et al. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of the wire+ arc additive manufacturing Al-Cu alloy. Addit. Manuf. 47, 102298 (2021).

Long, X., Lu, C., Su, Y. & Dai, Y. Machine learning framework for predicting the low cycle fatigue life of lead-free solders. Eng. Fail. Anal. 148, 107228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107228 (2023).

Motghare, S. V., Ashtankar, K. M. & Lautre, N. K. Experimental investigation of electrochemical and mechanical properties of stainless steel 309L at different built orientation by cold metal transfer assisted wire arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 109382 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of the austenitic stainless steel 316L fabricated by gas metal arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 703, 567–577 (2017).

Chen, X., Li, J., Cheng, X., Wang, H. & Huang, Z. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of austenitic stainless steel 316L using arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 715, 307–314 (2018).

Frazier, W. E. Metal additive manufacturing: A review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 23, 1917–1928 (2014).

Long, X. et al. An insight into dynamic properties of SAC305 lead-free solder under high strain rates and high temperatures. Int. J. Impact Eng. 175, 104542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2023.104542 (2023).

Holmes, M. Additive manufacturing in aerospace. Met. Powder Rep. 69(6), 3 (2014).

Bai, P. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy fabricated by cold metal transfer wire arc additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 27, 5805–5821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.10.265 (2023).

Wang, L., Xue, J. & Wang, Q. Correlation between arc mode, microstructure, and mechanical properties during wire arc additive manufacturing of 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 751, 183–190 (2019).

Liao, L. et al. Effect of cold-rolling and annealing temperature on microstructure, texture evolution and mechanical properties of FeCoCrNiMn high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.09.124 (2024).

Farabi, N., Chen, D. L. & Zhou, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of laser welded dissimilar DP600/DP980 dual-phase steel joints. J. Alloy. Compd. 509(3), 982–989 (2011).

Kopf, T. et al. Process modeling and control for additive manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V using plasma arc welding-methodology and experimental validation. J. Manuf. Process. 126, 12–23 (2024).

Ramazani, A. et al. Micro–macro-characterisation and modelling of mechanical properties of gas metal arc welded (GMAW) DP600 steel. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 589, 1–14 (2014).

Karabulut, B., Ruan, X., MacDonald, S., Dobrić, J. & Rossi, B. Fatigue of wire arc additively manufactured components made of unalloyed S355 steel. Int. J. Fatigue 184, 108317 (2024).

Zang, Y. et al. Resistance spot welded NiTi shape memory alloy to Ti6Al4V: Correlation between joint microstructure, cracking and mechanical properties. Mater. Design 253, 113859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2025.113859 (2025).

Long, J. et al. Printing dense and low-resistance copper microstructures via highly directional laser-induced forward transfer. Addit. Manuf. 103, 104755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2025.104755 (2025).

Ahsan, M. R. U. et al. Fabrication of bimetallic additively manufactured structure (BAMS) of low carbon steel and 316L austenitic stainless steel with wire+ arc additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 26(3), 519–530 (2020).

Shen, Q., Xue, J., Zheng, Z., Yu, X. & Ou, N. Effects of heat input on microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiMo0.2 high-entropy alloy prepared by wire arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Charact. 215, 114190 (2024).

Shanthar, R., Chen, K. & Abeykoon, C. Powder-based additive manufacturing: A critical review of materials, methods, opportunities, and challenges. Adv. Eng. Mater. 25(19), 2300375 (2023).

Dalpadulo, E., Petruccioli, A., Gherardini, F. & Leali, F. A review of automotive spare-part reconstruction based on additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 6(6), 133 (2022).

Tomar, B., Shiva, S. & Nath, T. A review on wire arc additive manufacturing: Processing parameters, defects, quality improvement and recent advances. Mater. Today Commun. 31, 103739 (2022).

Li, Y., Su, C. & Zhu, J. Comprehensive review of wire arc additive manufacturing: Hardware system, physical process, monitoring, property characterization, application and future prospects. Results Eng. 13, 100330 (2022).

Gurmesa, F. D., Lemu, H. G., Adugna, Y. W. & Harsibo, M. D. Residual stresses in wire arc additive manufacturing products and their measurement techniques: A systematic review. Appl. Mech. 5(3), 420–449 (2024).

Li, R. et al. Application of unsupervised learning methods based on video data for real-time anomaly detection in wire arc additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 143, 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2025.03.113 (2025).

Espera, A. H., Dizon, J. R. C., Chen, Q. & Advincula, R. C. 3D-printing and advanced manufacturing for electronics. Progr. Addit. Manuf. 4, 245–267 (2019).

Diegel, O., Nordin, A. & Motte, D. A Practical Guide to Design for Additive Manufacturing 226 (Springer, 2020).

Zhao, G. et al. Experimental and temperature field simulation study of Inconel 718 surface cladding based on vacuum electron beam heat source. Surf. Coat. Technol. 470, 129889 (2023).

Suryakumar, S., Karunakaran, K. P., Chandrasekhar, U. & Somashekara, M. A. A study of the mechanical properties of objects built through weld-deposition. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 227(8), 1138–1147 (2013).

Xiong, J., Zhang, G. & Zhang, W. Forming appearance analysis in multi-layer single-pass GMAW-based additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 80, 1767–1776 (2015).

Sadhya, S., Khan, A. U., Kumar, A., Chatterjee, S. & Madhukar, Y. K. Development of concurrent multi wire feed mechanism for WAAM-TIG to enhance process efficiency. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 51, 313–323 (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal University Jaipur.

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. Shunmugesh: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Snobin Mathew: Data Acquisition, Arun Raphel: Project administration; Raman Kumar: Supervision, Ashish Goyal :Funding Acquisition, Review the final draft. Ramachandran T: Instrumentation, Abhijit Bhowmik: Review the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shunmugesh, K., Mathew, S., Raphel, A. et al. Investigation of wire arc additive manufacturing of cylindrical components by using cold metal transfer arc welding process. Sci Rep 15, 21599 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05434-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05434-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A review of cytotoxicity testing methods and in vitro study of biodegradable Mg-1%Sn-2%HA composite by elution method

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine (2025)