Abstract

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common ocular condition that has been estimated to affect ~ 10 to 55.4% of the global population. Symptoms of DED include eye irritation, ocular pain and discomfort, inflammation, and photophobia, and, if left untreated, can lead to infection, corneal neuropathy, corneal scarring and impaired vision. Studies have shown that over 70% of all DED cases are caused by some form of Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). To date the etiology of MGD remains unknown, therefore, there is a need for further research into understanding the development, homeostasis and pathology of the Meibomian gland (MG). Various animal models, such as, the murine, rabbit and canine models, have provided valuable insights into the physiopathology of MGD, however, there are many limitations when comparing these models to human MGD. The nonhuman primate (NHP) model is closely related to humans and develops many diseases comparable to humans. This study aimed to characterize the anatomy and morphology of the NHP Macaca mulatta MGs compared to humans. MGs were analyzed by whole mount imaging and histology in the eyelids of NHPs of various ages ranging from ~ 3 months to 12 years. NHPs presented serially arranged MGs within the upper and lower tarsal plate with similar gland morphology to that of humans. Curiously, in the upper lid, the centrally located glands presented a distal portion that is thinner than the remaining glands, with meibocytes directly lining the central collecting duct instead of forming acinar structures. MG atrophy and drop-out were evident in both upper and lower eyelids of NHPs from 6 years of age, increasing in severity with age. Both MG tortuosity and hooking were observed in the NHPs at all ages, being more prevalent in the lower eyelids than in the upper eyelids. Taken together, our findings show that the NHP could be a valuable model for studying MG development, homeostasis and pathology, including Age Related MGD (ARMGD).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meibomian Glands (MGs) are modified sebaceous glands located within the tarsal plates (TP) of both the upper and lower eyelids that are responsible for the secretion of meibum onto the ocular surface1,2. In humans, MGs are linear tubulo-acinar glands composed of a central collecting duct lined by acini that lie perpendicular to the eyelid margin and extend into the tarsal plate2. In humans, rabbits, dogs and mice, the glands in the upper eyelid are slightly longer than those in the lower eyelid, reflecting the larger TP size3. In humans, there are approximately 25–40 MGs in the upper eyelids and 20–30 in the lower eyelids2,4 which are usually arranged in a highly ordered fashion ensuring a uniform distribution of lipids. Meibum is produced via holocrine secretion, a process that involves the proliferation of basal cells to produce meibocytes that move into the acini1,5. As these meibocytes move into the acini towards the collecting duct, they produce and accumulate meibum2, and as they reach the opening of the collecting duct, they become hyper mature and disintegrate, releasing their contents into the ductule. From the ductules, meibum then travels down the central collecting duct and is deposited onto the ocular surface via an orifice located at the eyelid margin. The ductile system is lined with stratified squamous epithelia6. The mechanical pressure caused by blinking is believed to aid in the extrusion of meibum through the collecting duct and out of the orifice located at the eyelid margin7. The action of blinking is also necessary for mixing meibum into the tear film and evenly spreading it over the ocular surface8. Thereafter, meibum forms the outer lipid layer of the tear film and is essential for stabilizing and preventing evaporation of the aqueous layer. Thus, the MGs have a pivotal role in maintaining ocular surface integrity, hydration, and health9. MGs may undergo gland atrophy and drop-out, leading to MG dysfunction (MGD)10. MGD leads to changes to the meibum produced, which causes tear film instability and increased tear evaporation, culminating in dry eye disease (DED)10,11,12. The pathogenesis of MGD remains largely unknown, however, aging has been identified as a major risk factor. The impact of aging on MGs has been studied in detail using the mouse model, showing that a decrease in proliferation of the MG basal cells and a loss of progenitor cells within the MG may contribute towards MG atrophy and dropout leading to age-related MGD (ARMGD)13,14.

Over the years, various animal models, including mice15, rats16, rabbits17, and canines18, have been instrumental in studying the anatomy and physiology of MGs and the pathogenesis of MGD5. The anatomical arrangement of the MGs within the tarsal plates of both the upper and lower eyelids in these animal models closely mirrors that of the human MGs5. Studies have shown that the composition of the meibum in the murine model closely resembles that of humans, making it a valuable model for studying meibum secretion and its impact on MG and ocular surface homeostasis19. Further, the murine model has been shown to naturally develop MGD with age, making it an extremely useful model for studying ARMGD20. However, a significantly lower blinking rate, smaller size and lower level of complexity are major limitations when correlating findings in the murine model to humans5,21,22,23,24. The rabbit model is more anatomically comparable to humans with significantly larger MGs than mice17. Thus, the rabbit model is often considered a more appropriate model for certain MG studies, such as inducing MGD via injury, such as cauterization. However, the composition of meibum in the rabbit model has been shown to be less similar to that of humans when compared to the murine model5. The rabbit model also presents a very distinct blinking rate when compared to humans24,25. Over the years, there have been many reports of MGD in domestic dogs18, with the canine model being shown to naturally develop age related MGD, thus making them a potential model to study the etiology of ARMGD26. The blink rate in dogs is similar to that of humans and the dimensions of the ocular surface of some breeds of canines are similar to humans22,27,28. The use of the canine model in experimental research is highly controversial, however various insights into MGD can be obtained from clinical assessments and management of domestic dogs within a veterinary setting.

Although the animal models described to date have provided invaluable insights into the anatomy and pathophysiology of the MG, there is still an unmet need for an animal model which more closely resembles the anatomy and physiology of humans and can more accurately recapitulate the pathophysiology of human MGD. Non-human primates (NHP), such as the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), a species of old-world monkey, are the closest species to humans which are permissible research models29. Thus, this model could serve as an invaluable model for studying the MG and MGD. However, little is known about the anatomy and morphology of the MG in the NHP. Herein we characterize the anatomical and morphological features of the MG in the Macaca mulatta compared to humans and we identified and characterized pathological changes that occur with aging.

Experimental procedures

Collection and processing of eyelids

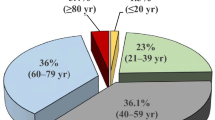

Human donor eyelids of 47, 70 and 80 years of age were obtained from National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI—Philadelphia, PA) and immersion fixed in 10% formalin and stored at 4 °C until use. The human samples obtained were de-identified and obtained without any personal identifiers, and, thus, were determined to be exempt from Institutional Review board (IRB) oversight in accordance with U.S. regulation 45CRF 46.104. The use of human tissues adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and prior informed consent was obtained for the use of tissues in research. Eyelids were obtained from sixteen rhesus monkeys (M. mulatta) ranging from 102 days to 12 years that were maintained at the Animal Care Operations (ACO) of the University of Houston. All eyelids included in this study were obtained from animals that were part of other studies that had no effect on the health of the ocular surface and MGs that were being conducted at the College of Optometry. When possible, both right eyelids (oculus dexter—OD) and left eyelids (oculus sinister—OS) were collected. The euthanasia procedure for M. mulatta was performed by ACO veterinary staff via sedation with ketamine (5–20 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (0.0075–0.02 mg/kg) intramuscularly. Once sedated, pentobarbital (100–150 mg/kg) was given intravenously. Cardiac auscultation was used to confirm the absence of a heartbeat for at least 1 min post euthanasia. For animals above 1 year of age, animals were flushed with pre-warmed PBS solution followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer. Thereafter, both upper and lower eyelids were obtained via dissection by an experienced surgeon. For animals younger than 1-year, fresh eyelids were collected, and immersion fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Electron Microscopy Sciences) overnight at 4 °C. Eyelids were washed with 1X PBS and tarsal plates isolated for whole mount imaging. A total of six M. mulatta < 3 months, three M. mulatta 6 months of age, two M. mulatta 6 years, one M. mulatta of 10 years, two M. mulatta of 11 years, and two M. mulatta of 12 years were included in this study. All animal procedures were previously approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Houston and conformed to the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines30.

Whole mount imaging

Human and M. mulatta eyelids were trimmed under a dissecting microscope (Leica S9E, Leica Microsystems Inc., IL, USA) to allow visualization of the MGs and to enable flat mounting for imaging. Excess connective tissue and skin were removed using a pair of microsurgical scissors. Digital images were acquired of the human MGs with both the conjunctival and skin surface facing upwards and digital images were acquired of the M. mulatta MGs with the conjunctival surface facing upwards under a fluorescence stereomicroscope Discovery.V12 with an Axiocam 503 color camera (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) under the white light.

Histological processing

The isolated tarsal plates were submerged in 30% sucrose overnight at 4 °C. Thereafter, tissues were flat mounted and embedded in Tissue-Tek embedding medium (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc.) with the conjunctival side facing upwards in order to obtain coronal sections through the MGs. 10 µm sections were obtained using a Leica CM 1950 cryostat (Leica Biosystems) and collected on Fisherbrand SuperfrostPlus Gold microscope slides (Fisher Scientific) and stored at − 20 °C until use. Upon use, slides were placed on a slide warmer at 50 °C for 30 min and the embedding medium washed with 1X PBS. Sections were then either stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin and mounted using Permount (Fisher Scientific) or Oil red O and counterstained with hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific) and mounted in Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech). Digital images were acquired of the sections under a DMi8 microscope (Leica).

Image analysis

The dimensions of the MGs were measured in images obtained from infants (3 months) and adult (PS at 6 years and PY at 10 years) NHPs using ImageJ software v1.53. Images of the eyelids obtained from PS and PY were selected for calculation of MG dimensions since they were the samples with the least atrophy and drop-out. Images were scaled from pixels to mm and the length of the glands was measured from the orifice at the lid margin to the apex. For the upper eyelids, the length of MGs at the nasal and temporal region (shorter glands) was measured and averaged, and the length of the glands in the central region (longer glands) was measured and averaged. Gland width was measured from the right lateral outer border to the left lateral border, and for the glands in the central upper lid the width of both the narrow and thicker glands was measured. At least 15 glands were measured in each eyelid for each measurement and tortuous glands and glands undergoing atrophy were excluded.

The number of distorted, tortuous and hooked glands were counted in digital images acquired of the whole-mounted eyelids by two independent investigators in a blinded manner. The outline of the MGs was drawn using the Curvature Pen Tool using Adobe Photoshop. The number of atrophic MGs and the number of glands that had undergone drop-out were counted in digital images acquired of the whole-mounted eyelids by two independent investigators in a blinded manner.

Statistics and analysis

All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Whenever possible, the analysis was carried out in a blinded manner to avoid bias. Statistical analysis was conducted using the unpaired student t-test when comparing two data sets or ANOVA followed by an appropriate post hoc test for multiple comparisons considering P < 0.05 as statistically significant. Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 and Microsoft Excel. Unless stated otherwise, error bars represent standard deviation (SD). All datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Morphological and histological analysis of the MG in the M. mulatta eyelid

TPs were isolated and prepared for whole mount imaging in order to visualize the overall structure of the MGs in the M. mulatta eyelid. A whole mount image of a representative eyelid of a 6-month M. mulatta is shown in Fig. 1. MGs were found to be distributed in parallel along the TP in both the upper and lower eyelids oriented perpendicular to the eyelid margin, similar to what is observed with humans, rabbits, mice, and dogs (Fig. 1A). On average, ~ 30 to 40 MGs were found to be present in the upper eyelids, and ~ 25 to 36 MGs in the lower eyelids (Fig. 1A). Overall, morphologically the MGs of M. mulatta were very similar to those of humans, however, with one notable difference. In the upper lid of the M. mulatta, the ~ 17 to 23 central MGs were longer than the remaining MGs (Fig. 1A), with the two thirds of the length of the glands furthest from the eyelid margin being significantly thinner than the remaining MGs (Fig. 1C,D). Furthermore, within these narrow glands, the acinar cells were not organized into acini that secrete into ductules surrounding the collecting duct, instead they were organized as acinar cells directly surrounding the central collecting duct (Fig. 1C,D, respectively). In contrast, the MGs present in the lower eyelid presented the same anatomical distribution as seen in humans (Fig. 1E,F)31. When comparing the dimensions of the MGs between the M. mulatta and humans, the average length of a M. mulatta gland in the temporal and nasal region of the upper lid of an infant was approximately 2.4 mm and in the adult approximately 2.9 mm, while in the central region of the upper lid in the infant was approximately 4.7 mm and in the adult approximately 5.4 mm, when compared to approximately 5.5 mm in the upper human eyelid2. The average MG length in the lower lid for infants was approximately 2.4 mm and for adults was approximately 3.4 mm, compared to the reported 2–5 mm in adult humans. The average width of a thicker gland in the upper lid of the M. mulatta in infants was 0.32 mm and adults were 0.48 mm, and of the thinner portion of the gland in the upper lid of the M. mulatta infants was 0.12 mm and in the adults 0.17 mm, when compared to 0.49 mm in the upper human eyelid. The width of a gland in the lower lid of the M. mulatta infants was 0.30 mm and in adults it was 0.44 mm. The central collecting duct had a larger caliber and was a more prominent feature in the human MG when compared to the M. mulatta MG (Figs. 1 and 2).

Anatomical and morphological features of the MGs of M. mulatta. (A) Eyelids were collected from M. mulatta and cleaned for whole mount imaging of the upper and lower MGs. A representative image was selected from a young M. mulatta (< 3 months) (B) The eyelids were then flat mounted and embedded for frozen sectioning to obtain coronal sections through the MGs. M. mulatta MGs were stained with H&E and digital images acquired of a section of the upper (B) and lower (E) eyelid under a LEICA microsystem DMi8 Inverted Microscope using spiral imaging. The eyelid margin is oriented towards the bottom of the image. (C and D) Higher magnification images of areas demarcated with a c and d in B are shown to evidence the detailed organization of the MG acinar cells along the collecting duct. (F) Higher magnification image of area demarcated in f in panel E showing the central collecting duct with connecting acini. Scale bar in panel A represents 1 mm, scale bar in panels B and E represents 1000 µm and scale bar in panels C, D and F represents 100 µm.

Anatomical and morphological features of the MGs with human eyelids. Human upper eyelids were obtained and cleaned for whole mount imaging. Representative images are shown of the MGs from a 40 year old human from the skin side (A) and conjunctival side (B). (C) The eyelids were then flat mounted and embedded for frozen sectioning to obtain coronal sections through the MGs. The MGs were stained with H&E and a section scanned under a LEICA microsystem DMi8 Inverted Microscope using spiral imaging. The eyelid margin is oriented towards the bottom of the image. (D and E) Higher magnification images of areas demarcated by d and e in C showing a central collecting duct and surrounding acini in an area that is more proximal and distal to the eyelid margin, respectively. Scale bar in panel A represents 1 mm, scale bar in panel (C) represents 1000 µm and the scale bar in panels (D) and (E) represents 100 µm.

Lipid accumulation in the MGs of M. mulatta and human eyelids

Meibum production in the M. mulatta and human MG was visualized through Oil red O (ORO) staining. Lipid droplets were observed in the central ducts and acini of both the upper and lower eyelids of M. mulatta and humans (Figs. 3 and 4, respectively). As seen in holocrine glands, stronger ORO staining was evident in the meibocytes as they move into the acini towards the collecting duct opening in both the M. mulatta and human MGs. The ORO staining pattern of the meibocytes lining the thinner region of the MGs present in the upper eyelid of the M. mulatta (Fig. 3D,E) was similar to that of meibocytes organized in acini throughout the remaining glands indicating these regions serve a similar secretory function as the remaining gland (Fig. 3C–E).

Distribution of lipids throughout the MGs of M. mulatta. (A) ORO staining of a young (< 3 months) M. mulatta upper eyelid. (C, D, and E) Higher magnification images of areas demarcated by c, d, and e in panel A. (B) ORO staining of a young (< 3 months) M. mulatta lower eyelid. (F) Higher magnification of area demarcated by f in panel B showing ORO staining in the lower eyelid. Scale bar panels (A) and (B) represents 1000 µm and the scale bar represent 100 µm in (C), (D), (E) and (F).

Distribution of lipids throughout human MGs. (A) A section of a 40 year old female eyelid was stained with ORO and image under a LEICA microsystem DMi8 Inverted Microscope using spiral imaging. (B, C) Higher magnification images of areas demarcated by b and c in panel (A) showing the lipid droplets present in the central collecting duct, acini, and meibocytes of the upper eyelid. Scale bar panel (A) represents 1000 µm and for panels (B) and (C) represents 100 µm.

Presence of MG tortuosity in the M. mulatta eyelids

Previous reports have demonstrated that in humans, certain individuals present significant MG tortuosity instead of presenting MGs aligned in parallel along the eyelid margin32. MG tortuosity is the abnormal twisting, bending, distortion and overlapping of the glands and has been associated with certain MG pathologies32. Curiously, to the best of our knowledge, MG tortuosity has never been identified in any of the animal models studied to date. Interestingly, significant tortuosity was observed in the MGs of certain M. mulatta. Digital images were acquired of the whole mounted M. mulatta tarsal plates under white light and eyelids from two different 6 month old M. mulatta, one with limited MG tortuosity (Fig. 5A) and one with significant tortuosity (Fig. 5B) are presented. Upper lids are presented in the top panels and lower lids in the bottom panels (Fig. 5A,B,E,F). The outer border of the MGs in Fig. 5A and B were traced with a black line and presented beneath the images (Fig. 5C,D). The total number of tortuous glands in animals were counted per upper and lower eyelid for each animal included in our study and data presented in Table 1. MG tortuosity was observed in eyelids obtained from M. mulatta of all ages, including those from animals under 3 months of age (Fig. 5E,F). Further, tortuosity was observed equally and independently between the left and right eyes, with no significant link between the severity of tortuosity between the left and right eyelids. Representative images of the left and right eyelids of an animal of less than 3 months (110 days) are presented in Fig. 5E and F, respectively. Limited tortuosity was observed in the left eyelid, while more significant tortuosity was observed in the right eyelid (Fig. 5E,F). The total number of tortuous glands were counted in the upper and lower eyelids of animals 6 months and under, and data segregated for the left and right eyelids (Fig. 5G). Indeed, no statistically significant difference was found between the number of tortuous glands between the left and right eyelids. The number of tortuous glands were also counted in the eyelids over 6 months; however, these values were not included in Fig. 5G since they were skewed because of the significant loss of glandular tissue. Interestingly, overall, significantly less tortuosity was noted in the upper lid when compared to the lower lid, specifically, an average of ~ 1.4 tortuous glands were found in the upper lids compared to ~ 9.5 tortuous glands in the lower lids (Table 1; Fig. 5G). The increased tortuosity in the lower lid when compared to the upper lid was evident in all eyelids analyzed in this study.

MG tortuosity in the M. mulatta. (A) Representative whole mount images of the upper and lower MGs of a 6 month old M. mulatta showing minimal distorted, hooked, and tortuous glands. (B) Representative whole mount images of the upper and lower MGs of a 6 month old M. mulatta with many distorted, hooked, and tortuous glands. (C and D) The outline of the MGs in (A) and (B) were traced (black line) to aid in the visualization of the individual glands and presented. (E) Representative images of the MGs within the left eyelid of a young animal less than 3 months (110 days), (F) Representative image of the MGs within the right eyelid of the same young animal (110 days), and (G) The total number of tortuous glands in the left (OS) and right (OD) upper and lower MGs of M. mulatta at different ages were quantified and presented as a box plot. *Represents p ≤ 0.05 calculated using the unpaired student t-test and ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test yielding a similar outcome. Scale bar represents 1 mm.

Presence of ARMGD in the M. mulatta eyelids

Interestingly, M. mulatta presented MG atrophy, the presence of ghost glands, and MG drop-out, similar to that observed in humans (Fig. 6A,B). Ghost glands appear as hypo reflective when compared to healthy glands. A representative image of an eyelid from a 6, 10 and 12 year M. mulatta is shown in Fig. 6A. At 6 years of age, M. mulatta presented MG atrophy (indicated with arrows) in both the upper and lower lids, with both the thicker and thinner glands in the upper lid being susceptible to atrophy with aging. By 10–12 years most animals presented MG atrophy (indicated with arrows) and dropout (indicated with an asterisk), which was more severe in older animals (Fig. 6A). As observed with humans, not all M. mulatta developed MGD equally, with some animals presenting atrophy of almost all glands, while other animals of the same age presented mostly healthy glands with solely a few atrophic glands. The number of atrophic glands and MG drop-out were counted in the upper and lower lids and data presented in Table 2 and as scatter plots (Fig. 6B–E). As seen with humans, the number of atrophic glands and MG drop-out significantly increased in both the upper and lower eyelids with age, indicating M. mulatta develop age-related MGD (ARMGD). Our study indicates that MG atrophy develops equally in the upper and lower eyelids of M. mulatta. An example of a 12 year M. mulatta with severe MGD is shown in Fig. 6F, presenting atrophy of almost all glands. Further, some animals presented ghost glands, as indicated in the dashed rectangle in Fig. 5G.

Whole mount images of M. mulatta MGs at different ages. (A) Representative upper and lower whole mount images of MGs of 6 year, 10 year, and 12 year old M. mulatta. Arrows indicate MG atrophy and asterisks indicate MG dropout. (B) Scatter plot of the number of atrophic MGs (y-axis) present in the upper eyelid of M. mulatta per age (x-axis). (C) Scatter plot of the number of atrophic MGs (y-axis) present in the lower eyelid of M. mulatta per age (x-axis). (D) Scatter plot of the number of MG drop-out (y-axis) present in the upper eyelid of M. mulatta per age (x-axis). (E) Scatter plot of the number of MG drop-out (y-axis) present in the lower eyelid of M. mulatta per age (x-axis). (F) Representative images of the upper and lower whole mounted eyelid showing the MGs of a 12 year old M. mulatta with severe MGD. (G) Representative images of the upper and lower whole mounted eyelid showing the MGs of a 11 year old M. mulatta that presents ghost glands, indicated within the dashed rectangle. Scale bar represents 1 mm.

Anatomical and histological features of MG atrophy M. mulatta presenting MGD

The M. mulatta upper and lower eyelids were processed for histology, stained with H&E and entire MGs scanned under a LEICA microsystem DMi8 Inverted Microscope using the spiral mode (Figs. 7 and 8, respectively). Representative images of healthy and atrophic glands are shown in Fig. 7. When analyzing the healthy glands, the typical holocrine organization of the MG gland can be noted. Specifically, smaller proliferating basal cells were organized around the outer perimeter of the gland, while cells moving towards the center of the gland were enlarged and presented lipid accumulation. In contrast, atrophic glands were thinner than healthy glands and there was a change in the usual holocrine distribution of cells (Fig. 7—middle panels). Specifically, there was a notable loss of the smaller proliferating basal cells around the outer perimeter of the gland and fewer mature cells (smaller in size and containing fewer lipids) moving towards the center of the gland.

Histological features of healthy MGs (top row), MGs undergoing atrophy (middle row), and regions that have undergone MG drop out (bottom row) in the upper eyelids M. mulatta. Representative regions of the MG are shown as a whole mount image (first image), and the same region is then shown following H&E staining (middle image). The area demarcated in the representative H&E image (middle panel) is then shown in higher magnification to the right (last panel). The solid arrows indicate areas presenting a residual central collecting duct following MG atrophy/drop-out. The empty arrow indicates a region of the MG that has undergone atrophy within a more central region of a MG. Scale bars in whole mount images represent 1 mm and the scale bar within the histological images represents 100 µm.

Histological features of healthy and atrophic glands in the lower eyelid of M. mulatta. Anatomical and histological features of healthy MGs (top two images) and MGs undergoing atrophy (bottom two images) in the lower eyelids M. mulatta. A representative whole mount image is presented of a 6 year M. mulatta demonstrating healthy glands. The eyelid was then processed for histology and stained with H&E digital images acquired using spiral imaging and a representative H&E image of the area indicated by a dashed rectangle within the whole mounted image is shown below. A representative whole mount image is presented of a 12 year M. mulatta demonstrating atrophic glands. The eyelid was then processed for histology and stained with H&E and digital images acquired using spiral imaging and a representative H&E image of the area indicated by a dashed rectangle within the whole mounted image is shown below. Scale bars in whole mount images represent 1 mm and the scale bar within the histological images represents 100 µm.

In NHPs, MG atrophy occurred primarily from the apex of the gland with the gland degenerating from the outer end towards the eyelid margin. However, in the upper eyelids, some areas of MG atrophy were also observed in central areas of the glands, yielding areas of MG atrophy that were flanked by areas of healthy MGs, indicated by an empty arrow. In the lower eyelid, MG atrophy occurred from the apex of the gland with no areas of atrophic tissue noted in central areas of the gland in the lower lid (Fig. 8). When analyzing the MG wholemount digital images, areas of the eyelid that previously contained MGs that underwent atrophy or drop-out, visually appear clear. However, when analyzed by histology, these areas of the eyelid that presented MG atrophy and drop-out no longer presented acinar cells, however, remnants of the collecting duct were still present, as indicated with full black arrows (Fig. 7—bottom panel).

Discussion

In this study we analyzed the overall anatomy and morphology of MGs in the NHP rhesus monkeys Macaca mulatta at various ages ranging from ~ 3 months to 12 years. Overall, we found that the M. mulatta presented similar anatomical and morphological features to the human MG. The human MGs are serially arranged within the tarsal plate of the upper and lower eyelids. They are composed of clusters of acini surrounding a long central duct connected by smaller ductules. The central duct extends into the tarsal plate from the eyelid margin with its orifice anterior to the mucocutaneous junction2,33. The individual glands are approximately 5.5 mm long in the upper eyelid and 2 mm long in the lower eyelid2. There are approximately 10–15 secretory acini in each individual gland with a higher number reported for the upper eyelid than in the lower eyelids2. M. mulatta also presents serially arranged MGs that extend into the tarsal plate that line both the upper and lower eyelids. Curiously, different to the human MG, the M. mulatta present glands that are uneven in length in the central area of the upper eyelid, with them being longer in the central portion of the eyelid with the part of the gland that is furthest from the eyelid being smaller in diameter. While the MGs in the lower eyelid are more evenly sized and organized, similar to what is observed in the humans and other species studied to date. The purpose for the long narrow glands that extend into the tarsal plate in the M. mulatta remains unclear, however the acini within the narrow glands produce lipids in a similar manner to the remaining MG. Overall, we found that the size of the MGs in the M. mulatta are slightly shorter and thinner than those in humans. The acini in the thicker M. mulatta glands are smaller and contain fewer meibocytes when compared to the MG acini in humans, however the overall organization of these glands is very similar to that in humans. The glands in the thinner areas differ in organization to that of humans, lacking acinar structures, with instead meibocytes directly lining the central collecting duct and releasing their contents directly into the central collecting duct.

In humans, gland tortuosity is a common occurrence in both upper and lower eyelids, however, what leads to MG tortuosity and whether there is a physiological purpose or consequence for the tortuosity remains elusive34. MG tortuosity has never been reported in the animal models studied to date. Curiously, in the present study we observed that gland tortuosity was a prominent feature in the MGs of M. mulatta, with most animals presenting at least one tortuous gland. As in humans, some M. mulatta presented extreme levels of MG tortuosity while others presented minimal tortuosity. Interestingly, tortuosity was observed in eyelids obtained from M. mulatta of all ages, including those from animals under 3 months of age, indicating tortuosity can occur during development and does not necessarily occur as a consequence of pathological states in M. mulatta. In the M. mulatta, we found that the presence of hooked and tortuous glands was a more prominent feature in the lower lid than the upper lid, whereas, in humans, MG tortuosity has been reported as a more prominent feature in the upper lid34,35. Thus, based on our findings with the M. mulatta, the presence of tortuosity cannot be directly associated with the increased length of the glands, as previously postulated. No significant link was found between the severity of tortuosity between the left and right eyelids, indicating that animals are not necessarily predisposed to MG tortuosity in both eyelids, and it can occur independently in one eyelid and not in the other. Previous studies have suggested that tortuous glands bend in order to fit within the available space during development, and reduced meibum expression has been correlated with greater gland tortuosity36,37. However, a study conducted on healthy subjects under 17 years indicated that tortuosity does not correlate with dry eye symptoms21. Therefore, whether MG tortuosity predisposes individuals to MGD remains to be established. Since tortuosity has never been reported in the rabbit, rat or murine models, we could speculate it is a phenomenon that only occurs in species with glands beyond a certain length. Based on our findings, we propose the M. mulatta could serve as a valuable model for studying the causes and potential consequences for MG tortuosity.

Evaporative DED (EDED) is characterized by an instability of the tear film and an increase in tear evaporation18,34. MGD is responsible for over 70% of EDED cases and is characterized by glandular atrophy and dropout which leads to altered meibum expression and/or changes in meibum composition. Herein, we found that from 6 years, M. mulatta presented MG atrophy and dropout in both the upper and lower lids. By 12 years, most M. mulatta presented significant MG atrophy and drop-out. Ghost glands have previously been described in humans as pale glands with abnormal MG architecture34,35. Ghost glands were also observed in the M. mulatta, and based on our histological analysis, acini within the ghost glands of the M. mulatta upper lid present early signs of acinar atrophy. This is similar to what was previously observed in the human and murine model20. Although the etiology of MGD remains unknown, the major risk factor identified to date is aging, with estimates that 70% of the population above 60 present MGD38. Studies have suggested that Rhesus macaques age at about 3 times the rate of humans, with puberty occurring between 2.5 and 4.5 years, a median life span of 27 years, and a maximum life span of ∼40 years39. They sexually mature around the ages of 2.5 and 3.5 years. and become adults by 8 years of age39. In general, rhesus macaques at 15–22 years are considered middle aged, while those over 30 years are considered old or elderly40. 75% of healthy human adults aged 25–66 years old have been reported to have MG atrophy37,41. Most recently a study conducted on pediatric patients aged 4–17 years found that 42% of subjects showed MG atrophy and 37% showed MG tortuosity, however these individuals were asymptomatic37. No significant associations were found between age, sex, or race with early onset of MG atrophy or with MG tortuosity in humans37. Crespo-Treviño and colleagues recently conducted a study where they investigated the impact of MG morphology in healthy humans and those with EDED34. Of the 75 patients recruited (33 healthy and 42 with dry eye), both the healthy and dry eye subjects showed altered MG morphology. There was no difference in upper lid morphology between the two groups and both showed distortion, tortuosity, hooked glands, shortened glands, and ghost glands. In the lower lid, shorter glands were more prominent in dry eye patients than in healthy subjects, and they also found that ghost glands are more prominent in subjects greater than 40 years old34. In our study, we did not observe an increase in MG atrophy in the lower eyelid when compared to the upper eyelid in the M. mulatta.

Our previous work studying ARMGD in the murine model found that during ARMGD, MG atrophy occurs from the acini at the apex of the gland12,20. Interestingly, in the M. mulatta, we also found that MG atrophy occurred primarily within acini furthest from the eyelid margin, therefore at the apex of the gland. Research is needed to unveil how MG atrophy occurs in such a concerted manner, occurring primarily in the glands most distal from the eyelid margin. Curiously, in the M. mulatta, acinar atrophy was also evident occurring within centrally located regions of the gland. It remains to be established whether the atrophy occurring in these areas could be caused by a different pathological mechanism when compared to atrophy occurring from the apex of the gland. Studies have suggested that as humans age, MGs suffer a decrease in acinar basal cell proliferation, which leads to gland atrophy and drop-out10,12. Cellular aging, oxidative stress, hormonal changes, inflammatory processes, and structural changes in the eyelid have also been suggested to contribute towards ARMGD42. Recent studies have suggested that localized inflammatory cell infiltration may contribute towards some cases of MGD43,44. The MG presents a gradual increase in inflammatory cell infiltration with aging, which could contribute towards ARMGD12. In fact, the quality of meibum expressed in mice with MGD has been correlated with MG leukocyte infiltration, with CD45 + cells located within MG acini and/or ducts of MGs that produce meibum with reduced quality45. Whether the different causes of MGD could favor the progression of MG atrophy from the apex of the gland versus the central regions of the gland remains to be established. We propose that the M. mulatta could be a valuable model for studying the pathogenesis and progression of these two distinct forms of MGD.

This study also included the histological analysis of MGs from NHPs at different ages. Curiously, when analyzing areas of the eyelid that previously contained MGs that have undergone MG atrophy and drop-out by histology, we noted that in areas that no longer presented acinar cells, remnants of the collecting duct were still present. Thus, in the M. mulatta, with MGD, the acini disappear; however, curiously, the collecting duct remains. Importantly, this data suggesting that the central collecting duct remains after the acinar tissue has undergone atrophy has valuable applications for regenerative medicine.

NHPs are the closest animals to humans, with a high degree of genetic homology, closely related physiological and anatomical features, similar disease pathogenesis and similar immunological systems46. As such, NHPs are the preferred animal model for clinical trials because their overall physiology, particularly their response to infection, closely resembles that of humans. In some instances, other animal models, such as rodents, rabbits, pigs, and canines, which are popular in biomedical studies, have been shown to not yield results translatable to humans. Over the years, NHPs have been crucial for the development of vaccines and therapies for HIV/AIDS47,48, Hepatitis A and B49, and tuberculosis50. They have also made significant contributions to the field of vision science and the prevention of blindness, enabling researchers to understand various visual abnormalities51 and to understand ocular development, oculomotor function, optics, and binocular vision51. They have also been used to study the progression of complex ocular diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy, choroidal neovascularization, wet age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma52. However, limited studies have used the NHP model for studying the ocular surface and its accessory glands. A previous study analyzed the MG of the NHP, however, only focusing on identifying ultrastructural components of the MG collecting duct with the goal of identifying keratinized epithelium within the duct53. This study found that in the human, NHP, and rabbit, the MG is composed of a central collecting duct that is connected to short ductules connected to acini. Further, via electron microscopy, they found that the ductal epithelium consists of a basal cell layer, intermediate cell layer, and a horny cell layer53. Importantly, they found evidence of keratinized epithelium extending into the collecting duct, as seen in humans53. A recent study used the NHP model to induce dry eye via desiccating stress, however it did not include any anatomical or histological analysis54. In this model, Rhesus macaque monkeys were housed in an environmentally controlled room for 21–36 days, with regulated humidity, temperature, and airflow. Following desiccating stress, NHPs exhibited clinical symptoms similar to those of humans with DED, including increased corneal fluorescein staining and decreased tear-breakup time54, supporting our findings that the NHP is a valuable model for studying the pathogenesis and potential treatment options for MGD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide an in-depth analysis of the overall anatomy of the NHP MGs within the upper and lower eyelids. Further, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to carry out an anatomical and histological analysis of the MGs of NHPs at different ages, enabling the identification of key anatomical and pathological features, including MG tortuosity, ghost glands, MG atrophy, and MG drop-out. Further, our study is the first to include a histological analysis of regions of the eyelid following MG atrophy identifying that remnants of the central collecting duct persist after the surrounding acini have undergone atrophy. It is important to note that there are various ethical concerns with using the NHP model in research that must be considered when selecting the most appropriate model for a particular study. Further disadvantages of the NHP that should be considered are high costs, the need for specialized infrastructure and personnel requirements for maintaining NHPs, and ethical considerations. However, we propose that, as in our study, animals already enrolled in other studies that do not affect the ocular surface the eyelids could thereafter be used for studying the progression of MGD. Thus, in accordance with the 3Rs, scientific advancements can be achieved in the realm of MG development, homeostasis and pathology without utilizing additional NHPs.

Taken together, while animal models such as rodents, rabbits, and canines have been invaluable in studying the MG and MGD, there is still an unmet need for a model more closely related to humans. Table 3 highlights the similarities and differences between the major characteristics of the ocular surface of humans compared to the mouse, rabbit, canine and NHP models. NHPs share a high degree of genetic similarity with humans, and, thus, present similar physiological and pathological processes. NHP also presents comparable immune systems to humans, making them an excellent model for studying disease with an immune component55. Thus, NHPs are important models for translational research56. Our study shows that the MGs of the M. mulatta present similar morphological and physiological features to the MGs of humans. Further, we found that the NHP presents MG tortuosity and ARMGD with similar pathological features to humans. Therefore, we proposed the NHP could serve as an invaluable animal model for studying the progression of ARMGD and to study the efficacy of potential therapeutic developments for EDED.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MGs:

-

Meibomian glands

- TP:

-

Tarsal plates

- DED:

-

Dry eye disease

- MGD:

-

Meibomian gland dysfunction

- ARMGD:

-

Age-related Meibomian gland dysfunction

- NHP:

-

Non-human primates

- NDRI:

-

National disease research interchange

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- ACO:

-

Animal care operations

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- ORO:

-

Oil red O

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- EDED:

-

Evaporative dry eye disease

- OS:

-

Oculus sinister (left eye)

- OD:

-

Oculus dexter (right eye)

References

Verma, S. et al. Meibomian gland development: Where, when and how?. Differentiation 132, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2023.04.005 (2023).

Knop, E., Knop, N., Millar, T., Obata, H. & Sullivan, D. A. The international workshop on Meibomian gland dysfunction: Report of the subcommittee on anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the Meibomian gland. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-6997c (2011).

Knop, N. & Knop, E. Meibomian glands. Part I: anatomy, embryology and histology of the Meibomian glands. Ophthalmologe 106(10), 872–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00347-009-2006-1 (2009).

Andrews, J. S. The Meibomian secretion. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 13(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004397-197301310-00004 (1973).

Sun, M., Moreno, I. Y., Dang, M. & Coulson-Thomas, V. J. Meibomian gland dysfunction: What have animal models taught us? (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21228822.

Call, M., Fischesser, K., Lunn, M. O. & Kao, W.W.-Y. A unique lineage gives rise to the Meibomian gland. Mol. Vis. 22, 168–176 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Meibomian gland features in a Norwegian cohort of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. PLoS One 12(9), e0184284. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184284 (2017).

Wang, M. T. M. et al. Impact of blinking on ocular surface and tear film parameters. Ocul. Surf. 16(4), 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2018.06.001 (2018).

Ding, J. & Sullivan, D. A. Aging and dry eye disease (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2012.03.020.

Nien, C. J. et al. Effects of age and dysfunction on human Meibomian glands. Arch. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.69 (2011).

Nien, C. J. et al. Age-related changes in the Meibomian gland. Exp. Eye Res. 89(6), 1021–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2009.08.013 (2009).

Moreno, I., Verma, S., Gesteira, T. F. & Coulson-Thomas, V. J. Recent advances in age-related Meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD). Ocul. Surf. 30, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2023.11.003 (2023).

Jester, J. V., Parfitt, G. J. & Brown, D. J. Meibomian gland dysfunction: Hyperkeratinization or atrophy?. BMC Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-015-0132-x (2015).

Parfitt, G. J., Xie, Y., Geyfman, M., Brown, D. J. & Jester, J. V. Absence of ductal hyper-keratinization in mouse age-related Meibomian gland dysfunction (ARMGD). Aging 5(11), 825–834. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100615 (2013).

Nien, C. J. et al. The development of Meibomian glands in mice. Mol. Vis. (2010).

Dong, Z.-Y. et al. Evaluation of a rat Meibomian gland dysfunction model induced by closure of Meibomian gland orifices. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 11(7), 1077–1083. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2018.07.01 (2018).

Prasad, D. et al. A review of rabbit models of Meibomian gland dysfunction and scope for translational research. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 71(4), 1227–1236. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJO.IJO_2815_22 (2023).

Hisey, E. A., Galor, A. & Leonard, B. C. A comparative review of evaporative dry eye disease and Meibomian gland dysfunction in dogs and humans. Vet. Ophthalmol. 26(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/vop.13066 (2023).

Butovich, I. A., Wilkerson, A. & Yuksel, S. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism in aging Meibomian glands and its molecular markers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(17), 13512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241713512 (2023).

Verma, S., Moreno, I. Y., Sun, M., Gesteira, T. F. & Coulson-Thomas, V. J. Age related changes in hyaluronan expression leads to Meibomian gland dysfunction. Matrix Biol. 124, 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matbio.2023.11.002 (2023).

Adil, M. Y. et al. Meibomian gland morphology is a sensitive early indicator of Meibomian gland dysfunction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 200, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2018.12.006 (2019).

Sebbag, L. & Mochel, J. P. An eye on the dog as the scientist’s best friend for translational research in ophthalmology: Focus on the ocular surface. Med. Res. Rev. 40(6), 2566–2604. https://doi.org/10.1002/med.21716 (2020).

Hall, A. The origin and purposes of blinking. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 29(9), 445–467. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.29.9.445 (1945).

Tsubota, K. et al. Quantitative videographic analysis of blinking in normal subjects and patients with dry eye. Arch. Ophthalmol. 114(6), 715–720. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130707012 (1996).

Corsi, F. et al. Clinical parameters obtained during tear film examination in domestic rabbits. BMC Vet. Res. 18(1), 398. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03492-1 (2022).

Viñas, M., Maggio, F., D’Anna, N., Rabozzi, R. & Peruccio, C. Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), as diagnosed by non-contact infrared Meibography, in dogs with ocular surface disorders (OSD): A retrospective study. BMC Vet. Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2203-3 (2019).

Kitamura, Y. et al. Assessment of Meibomian gland morphology by noncontact infrared meibography in Shih Tzu dogs with or without keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Vet. Ophthalmol. 22(6), 744–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/vop.12645 (2019).

Zwiauer-Wolfbeisser, V., Handschuh, S., Tichy, A. & Nell, B. Morphology and volume of Meibomian glands ex vivo pre and post partial tarsal plate excision, cryotherapy and laser therapy in the dog using microCT. Vet. Ophthalmol. 26(Suppl 1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/vop.13057 (2023).

Nakamura, T., Fujiwara, K., Saitou, M. & Tsukiyama, T. Non-human primates as a model for human development. Stem Cell Rep. 16(5), 1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.03.021 (2021).

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D. G. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 8(6), e1000412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 (2010).

Srivastav, S., Hasnat-Ali, M., Basu, S. & Singh, S. Morphologic variants of Meibomian glands: Age-wise distribution and differences between upper and lower eyelids. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 10, 1195568. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1195568 (2023).

Lin, X. et al. A novel quantitative index of Meibomian gland dysfunction, the Meibomian gland tortuosity. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9(9), 34. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.9.9.34 (2020).

Wang, J., Call, M., Mongan, M., Kao, W. W. Y. & Xia, Y. Meibomian gland morphogenesis requires developmental eyelid closure and lid fusion. Ocul. Surf. 15(4), 704–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTOS.2017.03.002 (2017).

Crespo-Treviño, R. R., Salinas-Sánchez, A. K., Amparo, F. & Garza-Leon, M. Comparative of Meibomian gland morphology in patients with evaporative dry eye disease versus non-dry eye disease. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 20729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00122-y (2021).

Daniel, E. et al. Grading and baseline characteristics of Meibomian glands in meibography images and their clinical associations in the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) study. Ocul. Surf. 17(3), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2019.04.003 (2019).

Bilkhu, P., Vidal-Rohr, M., Trave-Huarte, S. & Wolffsohn, J. S. Effect of Meibomian gland morphology on functionality with applied treatment. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 45(2), 101402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2020.12.065 (2022).

Gupta, P. K., Stevens, M. N., Kashyap, N. & Priestley, Y. Prevalence of Meibomian gland atrophy in a pediatric population. Cornea 37(4), 426–430. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001476 (2018).

Chader, G. J. & Taylor, A. Preface: The aging eye: Normal changes, age-related diseases, and sight-saving approaches. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54(14), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12993 (2013).

Simmons, H. A. Age-associated pathology in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Vet. Pathol. 53(2), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985815620628 (2016).

Mattison, J. A. & Vaughan, K. L. An overview of nonhuman primates in aging research. Exp. Gerontol. 94, 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.005 (2017).

Yeotikar, N. S. et al. Functional and morphologic changes of Meibomian glands in an asymptomatic adult population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18467 (2016).

Galletti, J. G. & de Paiva, C. S. The ocular surface immune system through the eyes of aging. Ocul. Surf. 20, 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.007 (2021).

Ban, Y. et al. Morphologic evaluation of Meibomian glands in chronic graft-versus-host disease using in vivo laser confocal microscopy. Mol. Vis. 17, 2533–2543 (2011).

Matsumoto, Y. et al. The evaluation of the treatment response in obstructive Meibomian gland disease by in vivo laser confocal microscopy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 247(6), 821–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-008-1017-y (2009).

Wu, C. Y. et al. Topographical distribution and phenotype of resident Meibomian gland orifice immune cells (MOICs) in mice and the effects of topical benzalkonium chloride (BAK). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(17), 9589. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23179589 (2022).

Harding, J. D. Nonhuman primates and translational research: Progress, opportunities, and challenges. ILAR J. 58(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar/ilx033 (2017).

Van Rompay, K. K. A. Tackling HIV and AIDS: Contributions by non-human primate models. Lab Anim. (NY) 46(6), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1038/laban.1279 (2017).

Veazey, R. S. & Lackner, A. A. Nonhuman primate models and understanding the pathogenesis of HIV infection and AIDS. ILAR J. 58(2), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar/ilx032 (2017).

Lanford, R. E., Walker, C. M. & Lemon, S. M. The chimpanzee model of viral hepatitis: Advances in understanding the immune response and treatment of viral hepatitis. ILAR J. 58(2), 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar/ilx028 (2017).

Foreman, T. W., Mehra, S., Lackner, A. A. & Kaushal, D. Translational research in the nonhuman primate model of tuberculosis. ILAR J. 58(2), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar/ilx015 (2017).

Mustari, M. J. Nonhuman primate studies to advance vision science and prevent blindness. ILAR J. 58(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar/ilx009 (2017).

Loiseau, A., Raîche-Marcoux, G., Maranda, C., Bertrand, N. & Boisselier, E. Animal models in eye research: Focus on corneal pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(23), 16661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316661 (2023).

Jester, J. V., Nicolaides, N. & Smith, R. E. Meibomian gland studies: Histologic and ultrastructural investigations. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 20(4), 537–547 (1981).

Gong, L. et al. A new non-human primate model of desiccating stress-induced dry eye disease. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 7957. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12009-7 (2022).

Xue, Y. et al. Nonhuman primate eyes display variable growth and aging rates in alignment with human eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64(11), 23. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.64.11.23 (2023).

Tarantal, A. F., Noctor, S. C. & Hartigan-O’Connor, D. J. Nonhuman primates in translational research. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 10, 441–468. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-021419-083813 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 EY033024 to V.J.C.-T. and the Core Grant P30 EY07551.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IYM: Data curation, methodology, investigation, and contributed towards writing manuscript. ELC: Contributed towards data analysis and writing the manuscript. VJCT: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moreno, I.Y., Cilli, E.L. & Coulson-Thomas, V.J. Applied anatomy and morphology of Meibomian glands in the non-human primate. Sci Rep 15, 20749 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05452-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05452-9