Abstract

In light of the ERI exacerbated by health emergencies, stabilizing the working conditions of primary healthcare professionals and ensuring the consistent operation of the public health system has become a focal point of research. This study was designed to investigate the mechanisms by which ERI affects job performance among primary healthcare professionals in the context of health emergencies, as well as the mediating role of perceived social support and resilience. Participants were recruited from 54 primary healthcare institutions, with a total of 1,050 primary healthcare professionals included in the study. Data were collected using the Effort-Reward Imbalance Scale, Perceived Social Support Scale, Individual Resilience Scale, and Job Performance Scale to assess key variables. Hayes’ serial mediation model was applied to examine the interrelationships between these variables. The effects of the Effort-Reward-Imbalance and Job Performance were negatively correlated (P < 0.01). ERI influences job performance through three pathways: the mediating role of perceived social support, the mediating role of individual resilience, and the chain mediating role of both perceived social support and individual resilience. Perceived social support and individual resilience moderates the association between Effort-Reward-Imbalance and job performance among primary healthcare professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health emergencies pose significant challenges to the public health system1. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted critical role of primary healthcare institutions during such crises and taught us that meaningful engagement of the communities disproportionately affected by the public health emergency deserves our attention2. Research indicates that 80% of health emergencies occur at the community level3. Healthcare professionals within these organizations play a crucial role in managing health emergencies. In preventing and managing such crises, their prolonged exposure to high-pressure and high-intensity work environments often subjects them to significant physical and psychological stress4,5. Relevant studies showed that the positive rates of anxiety and depression among medical staff during the prevention and control of COVID-19 ranged from 23.2 to 40.0% and 22.8–37.0%, respectively6,7,8. This, in turn, increases the risk of diminished well-being and both physical and mental health issues, ultimately affecting their performance at work9,10.

The Effort-Reward imbalance (ERI) model, proposed by Siegrist based on the principle of reciprocity11, suggests that the effort individuals invest in their work should be appropriately compensated with remuneration, respect, and opportunities for career advancement. When the organizational environment creates an imbalance in Effort-Reward, it can adversely impact employee behavior and well-being, ultimately impairing their job performance12,13. The “high effort, low reward” nature of health emergency response work often increases the risk of mental health issues among primary healthcare workers. A meta-analysis of 41 studies found that the prevalence of ERI among healthcare workers ranged from 3.5 to 96.9%, which is much higher than that of the general population of 31.7%14. This imbalance can negatively affect their physical and mental well-being, as well as their working conditions, leading to a relatively high incidence of negative working conditions such as burnout, job dissatisfaction, absenteeism and a tendency to leave their jobs among healthcare workers15. Previous studies have demonstrated that ERI is significantly associated with adverse health outcomes among healthcare workers in Japan and China16,17. It also predicts negative consequences such as low job satisfaction and reduced work engagement18,19. During health emergencies, factors like increased workload20 and higher occupational risks21 may exacerbate the ERI among primary healthcare professionals, further harming their performance.

Perceived Social Support (PSU) is an essential resource that can alleviate psychological stress reactions, reduce mental tension, and enhance social adaptation through individuals’ connections with others22,23. It emphasizes personal perceptions and feelings of societal support24. Studies have shown that higher PSU is associated with lower psychological distress, reduced burnout, and greater self-efficacy25,26. During the COVID-19 pandemic, PSU served as a protective factor against stress for both the general population27 and healthcare workers28. According to resource conservation theory29, individuals experiencing ERI at work actively seek social support to counteract the resource depletion caused by psychological imbalance30. This process helps them manage occupational stressors and enhances workplace resilience.

Individual resilience (IR) refers to an individual’s adaptive capacity to maintain a relatively stable level of physiological functioning and mental health in response to stress or adverse events31,32. Research has shown that resilience protects mental health33,34 and helps healthcare professionals manage stress during public health emergencies35. Its protective role has also been observed during catastrophic events and disease outbreaks36. Some scholars suggest that strengthening resilience can help individuals mitigate the effects of negative events, such as effort-reward imbalance while preserving their positive mental attributes37. Additionally, studies indicate that resilience, social support, and mental health are positively correlated, with social support’s predictive effect on mental health mediated by resilience38,39. Thus, the ability of medical personnel to receive timely and effective social support during health emergency responses significantly influences their self-recovery capacity, which in turn affects their overall performance in emergencies.

In light of the ERI exacerbated by health emergencies, stabilizing the working conditions of primary healthcare professionals and ensuring the consistent operation of the public health system has become a focal point of research. As frontline workers in epidemic prevention and control, primary healthcare professionals require not only strong professional skills but also adaptability to changing environments and resilience. Strengthening the development and utilization of personal social support networks, as well as improving individual resilience, may serve as a crucial area for improvement40,41. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the situation of ERI among primary healthcare professionals in the context of health emergencies and analyze the mechanism of its effect on job performance and the mediating role of perceived social support and individual resilience. Although perceived social support and resilience have frequently been treated as moderators in stress–performance research, we conceptualize them here as mediators. According to Conservation of Resources Theory, chronic ERI depletes psychosocial resources—first perceived social support, then resilience—and it is this sequential resource loss that leads to poorer job performance29,42,43. Accordingly, we established a theoretical hypothesis model (shown in Figure. 1) and made the following hypotheses:

H1: Effort-Reward Imbalance can negatively predict primary healthcare professionals’ job performance.

H2: Effort-Reward Imbalance can indirectly predict primary healthcare professionals’ job performance through the mediating role of perceived social support.

H3: Effort-Reward Imbalance can indirectly predict primary healthcare professionals’ job performance through the mediating role of individual resilience.

H4: Effort-Reward Imbalance can indirectly predict primary healthcare professionals’ job performance through the chain mediation of perceived social support and individual resilience.

Methods

Participants and procedures

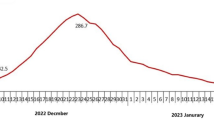

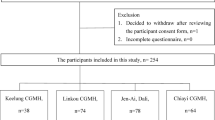

This research data was obtained from a cross-sectional survey of primary healthcare professionals in China during the COVID-19 epidemic period from September to December 2021. The study utilized stratified cluster sampling to survey Shandong Province, China. Three sample cities were selected based on economic development levels—high, medium, and low. Within each selected city, three counties (including cities and districts) were chosen according to the same criteria. From each county, six township or community health service centers were selected. Data were collected from all on-duty healthcare professionals at the selected primary institutions on the same day using whole cluster sampling. A total of 1,200 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,100 were returned, resulting in a recovery rate of 91.67%. Of these, 1,050 questionnaires were deemed valid, yielding a validity rate of 95.45%. To encourage voluntary participation, we circulated study details through institutional communications and briefings by department heads. Research assistants then visited each center on scheduled workdays to distribute paper questionnaires and collect completed forms via sealed boxes in private areas. All responses were strictly anonymous and confidential.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics

General characteristics, including the individual’s basic profile (gender, age, marital status, education level, etc.) and occupational status (years of work experience, average number of hours worked per week), were included based on a review of the literature.

Effort–Reward imbalance

Effort–Reward imbalance scale was compiled by German sociologist Siegrist in 1996 and introduced into China by Li in 200444. The scale consists of 23 items divided into three dimensions: effort (6 items), reward (11 items), and overcommitment (6 items). For example, a typical effort item reads “I have constant time pressure due to a heavy workload,” a reward item reads “I receive the respect I deserve from my superiors,” and an overcommitment item reads “When I get home, I often have trouble relaxing because of my work.” The scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree). The degree of Effort-Reward was calculated by the Effect-Reward Ratio (ERR). The degree of imbalance between the costs and benefits of the assessment is calculated using the Effort-Reward Ratio (ERR) as E/(R * C), where E is the total score of the effort dimension, R is the total score of the reward dimension, and C is the ratio of the number of effort dimension items to the number of reward items45. In the original validation, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.91 (effort), 0.87 (reward), and 0.85 (overcommitment). In our sample, overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.846, with individual coefficients of 0.831, 0.923, and 0.843 for the effort, reward, and overcommitment dimensions, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable model fit with the three components theoretical structure (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.069, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.079, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.881).

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was measured with a twelve-item scale developed by Blumenthal et al.46. This scale evaluates three dimensions: significant other support (4 items), family support (4 items) and friends support (4 items). For example, a representative item from the significant other support dimension reads “There is a special person who is around when I am in need,” a family support item reads “My family is willing to help me make decisions,” and a friends support item reads “I can share my happiness and sorrow with my friends.” Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating better perceived social support47. In the original validation, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.91 (significant other), 0.87 (family), and 0.85 (friends). In our sample, overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.949, with individual coefficients of 0.875, 0.881, and 0.900 for significant other, family, and friends support, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable model fit with the three components theoretical structure (SRMR = 0.025, RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.979).

Individual resilience

Individual resilience was measured using the Emergency Rescuer Resilience Scale designed by Liang48, which consists of four dimensions with a total of 24 items: rational coping (6 items), hardiness (5 items), self- efficacy (7 items) and flexible adaption (6 items). For example, a typical Rational coping item reads “I remain calm and logical when faced with unexpected problems,” a Hardiness item reads “I see challenges as opportunities to grow,” a Self-efficacy item reads “I trust my ability to handle emergencies,” and a Flexible adaptation item reads “I adjust my plans quickly when situations change.” The scale rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater resilience47. In the original validation, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.88 (rational coping), 0.85 (hardiness), 0.90 (self-efficacy), and 0.87 (flexible adaptation). In our sample, overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.966, with individual coefficients of 0.927, 0.905, 0.931, and 0.904 for rational coping, hardiness, self-efficacy, and flexible adaptation dimensions, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable model fit with the four components theoretical structure (SRMR = 0.044, RMSEA = 0.081, CFI = 0.923).

Job performance

Referring to the scale developed by Motowidlo et al.49, Chen designed a nine-item job performance scale tailored to the Chinese context50. The scale is divided into three dimensions: task performance (3 items), interpersonal facilitation (3 items), and job dedication (3 items) with a total of 9 entries. For example, a typical task-performance item reads “I complete my assigned duties thoroughly,” an interpersonal-facilitation item reads “I willingly help colleagues when they are busy,” and a job-dedication item reads “I am always willing to go the extra mile to get the job done.” Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating better job performance47. In the original adaptation, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.79 (task performance), 0.74 (interpersonal facilitation), and 0.81 (job dedication). In our sample, overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.889, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the task performance, interpersonal facilitation, and job dedication dimensions of 0.792, 0.743, and 0.806, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable model fit with the three components theoretical structure (SRMR = 0.031, RMSEA = 0.077, CFI = 0.975).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were initially calculated for the demographic and key study variables, followed by data standardization. Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess potential common method bias across all variables. To analyze the mediating effect, Hayes’ PROCESS macro (v4.0, Model 6) was employed51, with the ordinary least squares (OLS) method used to estimate the total, direct, and indirect effects, based on 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrap resamples. All analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1, with statistical significance set at 0.05.

Results

Common method deviation test

Common method bias refers to errors arising from using the same measurement environment and data source. In our study, effort - reward imbalance (ERI), perceived social support (PSU), individual resilience (IR), and job performance (JP) were all assessed via self-administered written questionnaires with 1–5 Likert scales at one time point, which may introduce common methodological variation. To test for common method bias, Harman’s single factor test was used to analyze all items of the key variables. The first factor explained 35.06% of the variance, which was below the standard threshold of 50%52. This indicated that there was no serious common method bias in this study and the data could be analyzed in the next step.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

A total of 1050 primary healthcare professionals were included in this study, of whom 307 (29.24%) were male and 743 (70.76%) were female. The average age was 38.09 ± 9.26 years and most participants were in the age groups of 41–50 years (35.71%) and 31–40 years (33.05%). The majority of participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher (58.10%) and earned CNY 20,001–60,000 per year (64.48%). Regarding years of experience, 20 years or more were predominant (32.00%), and the average workweek was highest at 48 h or less (59.14%). As shown in Table 1.

Differential testing of demographic characteristics

Table 2 illustrates the differences in Effort –Reward imbalance, perceived social support, individual resilience, and job performance across various demographic characteristics. Significant differences in Effort–Reward ratio by age, education level, annual income, working tenure, and weekly working hours among participants. Specifically, participants aged 41–50, with 16–20 years of working tenure, a Bachelor’s degree or higher, higher annual income, and longer weekly working hours had a higher Effort–Reward imbalance. Additionally, participants with varying marital statuses and weekly working hours reported different scores for perceived social support and individual resilience. Those who were married and had shorter weekly working hours had higher scores for both perceived social support and individual resilience. Furthermore, older participants, married and working over 20 years had a higher score for job performance.

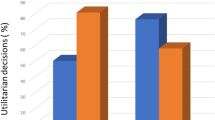

Bivariate correlations and internal consistency estimates

The correlation analysis was conducted to test the correlation between the variables, and the results showed that Effort – Reward imbalance, job performance, perceived social support, and individual resilience were correlated bilaterally. ERI was negatively related to perceived social support (r = − 0.32, p < 0.01), individual resilience (r = − 0.35, p < 0.01), and job performance (r = − 0.32, p < 0.01). Perceived social support was positively related to individual resilience (r = 0.65, p < 0.01) and job performance (r = 0.50, p < 0.001). Individual resilience was positively related to job performance (r = 0.64, p < 0.001). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) ranged from 0.85 to 0.97, which shows they were all adequate and closely match the developers’ original values53. More detailed correlation coefficients among the variables are presented in Table 3; Figure. 2.

Mediation analyses

Results of the mediating effects of perceived social support and individual resilience between the relationship of ERI and job performance are illustrated in Table 4. After controlling for the gender, age, marital status, education level, annual income, working tenure and weekly working hours, the results showed that ERI could significantly predict job performance (β= −1.646, p < 0.001), and hypothesis 1 is established. Also, ERI had a significant negative prediction of perceived social support (β= −8.639, p < 0.001) and individual resilience (β= −7.978, p < 0.001). Perceived social support had a significant positive predictive effect on individual resilience (β = 1.013, p < 0.001) and job performance (β = 0.075, p < 0.001). Finally, the individual resilience positively predicted job performance (β = 0.175, p < 0.001).

The results of the further chain mediation model tests are presented in Table 5; Fig. 3. In Path 1, the indirect effect of the path with perceived social support as the mediating variable is − 0.651 (95% CI = − 1.192, − 0.243). In Path 2, the indirect effect of the path with individual resilience as the mediating variable is − 1.398 (95% CI = − 2.102, − 0.817). In Path 3, the indirect effect with both perceived social support and individual resilience as mediating variables is − 1.534 (95% CI = − 2.466, − 0.877). The total of all indirect effects is − 3.583 (95% CI = − 5.033, − 2.501), with the effects of the three indirect paths accounting for 12.45%, 26.74%, and 29.34% of the total, respectively. Hypotheses 2–4 are confirmed. Contrasting findings were analyzed to determine whether specific indirect effects of mediators were stronger than others. The analysis revealed that the bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the difference between indirect effects 1 and 3 does not include a value of 0, indicating that path 1 is significantly different from path 3. Therefore, the chain mediating effect of ERI on job performance is established (Fig. 3).

Discussions

Utilizing a chain mediation model, the objective of this study was to explore the relationship between Effort-Reward Imbalance and job performance among primary healthcare professionals during health emergencies, as well as to examine the underlying mechanisms of influence. A chain mediation model was employed for analysis, indicating that ERI influences job performance through three pathways: perceived social support, individual resilience, and the interaction between perceived social support and individual resilience.

In our study, we examined the relationship between ERI and job performance, finding that ERI negatively predicts the job performance of primary healthcare professionals, consistent with previous research54,55. On the one hand, the manpower shortage and resource constraints in China’s primary healthcare institutions have been exacerbated by health emergencies, leading to increased workloads56; on the other hand, the pressure of epidemic prevention and control tasks has led to the collapse of the diagnosis and treatment volume of primary healthcare institutions, the lagging financial compensation has led to the imbalance of the efforts and rewards of primary healthcare workers during health emergencies57. This imbalance not only impacts the physical and mental well-being of healthcare workers but also undermines their motivation and affects the overall performance and efficiency of the public health system16,58.

Research has demonstrated the mediating role of perceived social support in the relationship between the effects of ERI on job performance, and previous studies have confirmed the relationship of social support between ERI and self-efficacy59. From a resource depletion perspective, chronic ERI erodes individuals’ PSU, which then diminishes their capacity to engage in work tasks effectively60. Primary healthcare workers with high levels of perceived social support are more likely to adopt positive coping strategies, such as actively seeking social support to counterbalance the resource depletion caused by psychological imbalance61, and minimizing the negative effects of the ERI62, thereby reducing its adverse impact on job performance.

In addition, we have also demonstrated the mediating role of individual resilience in the relationship between the effects of ERI on job performance. Individual resilience protects individuals from various negative emotions, such as stress, depression, and anxiety, which in turn enhances the professional skills and work engagement of primary healthcare professionals, ultimately improving job performance63,64. Previous research indicates that highly resilient primary healthcare professionals possess sufficient coping resources and positive emotions to effectively manage work-related stress65,66. In our model, ERI erodes this resilience which is the capacity to recover from adversity, and it is the subsequent decline in resilience that transmits ERI’s negative impact onto job performance.

The study further demonstrated the chain mediation effects of perceived social support and individual resilience on the relationship between ERI and job performance. It revealed a positive correlation between perceived social support and individual resilience, with social support serving as a crucial resource for managing stress and a key protective factor for resilience67. During health emergencies, primary healthcare professionals face not only the imbalance between effort and reward due to work-related stress but also the added burden of isolation from family, friends, and society68,69. Support from family and friends helps these workers achieve a work-life balance, boosting their resilience and enhancing their ability to cope with challenges. This, in turn, fosters a positive attitude and improves job performance. Research during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that individual resilience, coping behaviors, and social support played critical roles in safeguarding the mental health and well-being of frontline healthcare workers70,71,72. Therefore, when individuals perceive an imbalance between effort and reward, strong social support can reduce psychological stress and dissatisfaction, ultimately maintaining a positive outlook and enhancing job performance by strengthening individual resilience.

This study offers valuable insights into the psychological health and job performance of primary healthcare professionals during health emergencies. It emphasizes that ERI significantly affects both their psychological well-being and job performance. highlighting the need for targeted interventions. A sound performance appraisal mechanism for primary medical institutions is an important way to improve the return on work of primary medical personnel, so establishing long-term salary structures incorporating performance-linked adjustments during health emergencies and standardized hardship allowances for high-intensity roles, coupled with competency-based career progression frameworks that recognize specialized expertise in community medicine and emergency response, including accelerated advancement mechanisms for high-performing junior staff, will effectively mitigate ERI and preserve psychological health. Given the demands of health emergency work, primary healthcare professionals, especially those with fewer years of experience, younger staff, and longer weekly working hours, should be provided with comprehensive support systems, alleviate the imbalance between effort and reward, and improve job performance. Such systems should provide enhanced psychosocial support through accessible, confidential mental health services and professionally facilitated peer support networks, coupled with dedicated rest spaces during demanding shifts. In addition, Effective implementation depends on committed multilevel leadership, where health authorities establish dedicated funding streams and national well-being standards, while healthcare institutions integrate support mechanisms into operational workflows with rigorous evaluation of ERI reduction, psychological outcomes, and performance metrics essential for sustainable refinement.

There are some limitations in this study. First, data were collected from a single province in eastern China, which may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings. Future research should include diverse regions from central and western China. Second, as a cross-sectional study, it only identifies correlations between variables, rather than establishing causality. Additionally, the health emergency context may differ from the normative setting, so future studies should assess the findings’ robustness in a normative context. Finally, our reliance on self-reported data may introduce social-desirability and single-source biases. Although Harman’s single-factor test suggested that common method variance is not serious, this test has limited sensitivity and may not detect more complex method bias. Future research should incorporate multi-source performance evaluations, such as supervisor ratings or objective service-delivery metrics, and adopt mixed-methods designs that combine qualitative interviews with quantitative multi-source data to strengthen validity and mitigate method bias.

Conclusions

The study examined the relationship between Effort-Reward Imbalance, perceived social support, individual resilience, and job performance in health emergencies. The results confirmed that ERI negatively predicted job performance, with ERI also indirectly affecting job performance through the mediating roles of perceived social support and individual resilience, as well as the combined mediation of both factors. These findings highlight the importance of addressing the mental health of primary healthcare professionals in health emergencies. Providing adequate job support systems and establishing long-term salary increases and promotion channels can effectively mitigate the ERI issue and help maintain their mental well-being.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ERI:

-

Effort–Reward imbalance

- PSU:

-

Perceived social support

- IR:

-

Individual resilience

- JP:

-

Job performance

References

Ryan, B. et al. Strategies for strengthening the resilience of public health systems for pandemics, disasters, and other emergencies. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 17, e479. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2023.136 (2023).

Mensah, G. A. & Johnson, L. E. Community engagement alliance (CEAL): leveraging the power of communities during public health emergencies. Am. J. Public. Health. 114, S18–21. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307507 (2024).

Lichterman, J. D. Partnerships. A community as resource strategy for disaster response. Public Health Rep. 115, 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/115.2.262 (2000).

Stiawa, M. et al. Also stress Ist Jeden Tag – Ursachen und bewältigung von arbeitsbedingten fehlbelastungen Im krankenhaus Aus sicht der beschäftigten. Eine qualitative studie. Psychiatr Prax. 49, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1477-6000 (2022).

Pereira, E. C., Rocha, M. P. D., Fogaça, L. Z. & Schveitzer, M. C. Occupational health, integrative and complementary practices in primary care, and the Covid-19 pandemic. Rev. Esc Enferm USP. 56, e20210362. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-220x-reeusp-2021-0362 (2022).

Wu, T. et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 281, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117 (2021). Medline:33310451.

Pappa, S. et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 (2020). Medline:32437915.

Saragih, I. D. et al. Global prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 121, 104002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104002 (2021). Medline:34271460.

Coutinho, H., Queirós, C., Henriques, A., Norton, P. & Alves, E. Work-related determinants of psychosocial risk factors among employees in the hospital setting. WOR 61, 551–560. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-182825 (2019).

Heming, M. et al. Managers perception of hospital employees’ effort-reward imbalance. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 18, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-023-00376-4 (2023).

Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27 (1996).

Siegrist, J. & Li, J. Associations of extrinsic and intrinsic components of work stress with health: A systematic review of evidence on the Effort-Reward imbalance model. IJERPH 13, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040432 (2016).

Liang, H. Y., Tseng, T. Y., Dai, H. D., Chuang, J. Y. & Yu, S. The relationships among overcommitment, effort-reward imbalance, safety climate, emotional labour and quality of working life for hospital nurses: a structural equation modeling. BMC Nurs. 22, 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01355-0 (2023).

Le Huu, P., Bellagamba, G., Bouhadfane, M., Villa, A. & Lehucher, M-P. Meta-analysis of effort–reward imbalance prevalence among physicians. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 95, 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01784-x (2022).

Xiao, Y. et al. Burnout and Well-Being among medical professionals in china: A National Cross-Sectional study. Front. Public. Health. 9, 761706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.761706 (2022).

Sakata, Y. et al. Effort-reward imbalance and depression in Japanese medical residents. J. Occup. Health. 50, 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.l8043 (2008). Medline:18946190.

Wang, X., Liu, L., Zou, F., Hao, J. & Wu, H. Associations of occupational stressors, perceived organizational support, and psychological capital with work engagement among Chinese female nurses. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5284628 (2017).

Shang Guan, C-Y., Li, Y. & Ma, H-L. The mediating role of psychological capital on the association between occupational stress and job satisfaction among Township cadres in a specific Province of china: A Cross-Sectional study. IJERPH 14, 972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14090972 (2017).

Satoh, M., Watanabe, I. & Asakura, K. Occupational commitment and job satisfaction mediate effort–reward imbalance and the intention to continue nursing. Japan J. Nurs. Sci. 14, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12135 (2017).

Tang, C., Chen, X., Guan, C. & Fang, P. Attitudes and response capacities for public health emergencies of healthcare workers in primary healthcare institutions: A Cross-Sectional investigation conducted in wuhan, china, in 2020. IJERPH 19, 12204. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912204 (2022).

Seyedin, H., Rostamian, M., Barghi Shirazi, F. & Adibi Larijani, H. Challenges of providing health care in complex emergencies: A systematic review. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 17, e56. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.312 (2023).

Bareket-Bojmel, L., Shahar, G., Abu‐Kaf, S. & Margalit, M. Perceived social support, loneliness, and hope during the COVID‐19 pandemic: testing a mediating model in the UK, USA, and Israel. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 60, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12285 (2021).

Dong, Y. et al. The mediating effect of perceived social support on mental health and life satisfaction among residents: A Cross-Sectional analysis of 8500 subjects in Taian city, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 14756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214756 (2022). Medline:36429473.

Liu, Y., Aungsuroch, Y., Gunawan, J. & Zeng, D. Job stress, psychological capital, perceived social support, and occupational burnout among hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 53, 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12642 (2021).

Feng, D., Su, S., Wang, L. & Liu, F. The protective role of self-esteem, perceived social support and job satisfaction against psychological distress among Chinese nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 26, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12523 (2018). Medline:29624766.

Hu, S. H., Yu, Y., Chang, W. & Lin, Y. Social support and factors associated with self-efficacy among acute‐care nurse practitioners. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, 876–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14129 (2018).

Yu, H. et al. Coping style, social support and psychological distress in the general Chinese population in the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. BMC Psychiatry. 20, 426. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02826-3 (2020).

Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Li, S. & Yang, N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26 https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.923549 (2020).

Achdut, N. & Refaeli, T. Unemployment and psychological distress among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic: psychological resources and risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 7163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197163 (2020). Medline:33007892.

Sanecka, E., Stasiła-Sieradzka, M. & Turska, E. The role of core self-evaluations and ego-resiliency in predicting resource losses and gains in the face of the COVID-19 crisis: the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 36, 551–562. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.02113 (2023). Medline:37811685.

Bonanno, G. A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?? Am. Psychol. 59, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20 (2004).

Karoly, P. & Ruehlman, L. S. Psychological resilience and its correlates in chronic pain: findings from a National community sample. Pain 123, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.014 (2006). Medline:16563626.

Cho, E., Chen, M., Toh, S. M. & Ang, J. Roles of effort and reward in well-being for Police officers in singapore: the effort-reward imbalance model. Soc. Sci. Med. 277, 113878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113878 (2021).

Vu-Eickmann, P., Li, J., Müller, A., Angerer, P. & Loerbroks, A. Associations of psychosocial working conditions with health outcomes, quality of care and intentions to leave the profession: results from a cross-sectional study among physician assistants in Germany. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 91, 643–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-018-1309-4 (2018). Medline:29691658.

Cooper, A. L., Brown, J. A., Rees, C. S. & Leslie, G. D. Nurse resilience: A concept analysis. Int. J. Ment Health Nurs. 29, 553–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12721 (2020). Medline:32227411.

Labrague, L. J. & De Los Santos, J. A. A. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 1653–1661. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13121 (2020). Medline:32770780.

Tao, Y. et al. Perceived stress and psychological disorders in healthcare professionals: a multiple chain mediating model of effort-reward imbalance and resilience. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1320411. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1320411 (2023). Medline:38155891.

Li, J., Theng, Y-L. & Foo, S. Does psychological resilience mediate the impact of social support on geriatric depression? An exploratory study among Chinese older adults in Singapore. Asian J. Psychiatry. 14, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.01.011 (2015).

Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 38, 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003 (1976).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 (1985).

Hao, S. Burnout and depression of medical staff: A chain mediating model of resilience and self-esteem. J. Affect. Disord. 325, 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.153 (2023).

Sun, X., Yin, H., Liu, C. & Zhao, F. Psychological capital and perceived supervisor social support as mediating roles between role stress and work engagement among Chinese clinical nursing teachers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 13, e073303. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073303 (2023).

Chen, S-Y. et al. The mediating and moderating role of psychological resilience between occupational stress and mental health of psychiatric nurses: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 22, 823. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04485-y (2022).

Niedhammer, I., Tek, M-L., Starke, D. & Siegrist, J. Effort–reward imbalance model and self-reported health: cross-sectional and prospective findings from the GAZEL cohort. Soc. Sci. Med. 58, 1531–1541. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00346-0 (2004).

Topa, G., Guglielmi, D. & Depolo, M. Effort-reward imbalance and organisational injustice among aged nurses: a moderated mediation model. J. Nurs. Manag. 24, 834–842. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12394 (2016).

Blumenthal, J. A. et al. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom. Med. 49, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198707000-00002 (1987).

Wang, A-Q. et al. Association of individual resilience with organizational resilience, perceived social support, and job performance among healthcare professionals in Township health centers of China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 13, 1061851. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1061851 (2022).

Liang, A. Study on the resilience model and intervention based on coping with emergency. dissertation, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Available: https://lib.ucas.ac.cn/

Motowidlo, S. J. & Van Scotter, J. R. Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 79, 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.4.475 (1994).

Chen, Z. et al. Effect of healthcare system reforms on job satisfaction among village clinic Doctors in China. Hum. Resour. Health. 19, 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00650-8 (2021).

Hayes, A. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (the Guilford, 2013).

Podsakoff, P. M. & Organ, D. W. Self-Reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manag. 12, 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408 (1986).

Durand, F. & Fleury, M-J. The association between task interdependence and participation in decision-making: a moderated mediation model in mental healthcare. J. Interprof. Care. 38, 826–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2024.2383239 (2024).

Sérole, C. et al. The forgotten Health-Care occupations at risk of Burnout-A burnout, job Demand-Control-Support, and Effort-Reward imbalance survey. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63, e416–e425. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002235 (2021). Medline:34184659.

Nakagawa, Y. et al. Job demands, job resources, and job performance in Japanese workers: a cross-sectional study. Ind. Health. 52, 471–479. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2014-0036 (2014). Medline:25016948.

Chang, Y-T. & Hu, Y-J. Burnout and health issues among prehospital personnel in Taiwan fire departments during a sudden Spike in community COVID-19 cases: A Cross-Sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 2257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042257 (2022). Medline:35206444.

Yan, G. & LUO, H. L. Relationship between Effort-reward imbalance and job burnout among primary healthcare workers. Chin. Gen. Pract. 27, 2305–2311. https://doi.org/10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2023.0251 (2024).

Ge, J. et al. Effects of effort-reward imbalance, job satisfaction, and work engagement on self-rated health among healthcare workers. BMC Public. Health. 21, 195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10233-w (2021). Medline:33482786.

Zhu, Y. & Tao, Y. The relationship between Effort-reward imbalance and positive psychological capital of college students: the mediating role of social support. J. South. China Normal Univ. 54, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.6054/j.jscnun.2022035 (2022).

Wolff, J. C. et al. Negative cognitive style and perceived social support mediate the relationship between aggression and NSSI in hospitalized adolescents. J. Adolesc. 37, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.016 (2014). Medline:24793396.

Liu, S., Wang, Y., He, W., Chen, Y. & Wang, Q. The effect of students’ effort-reward imbalance on learning engagement: the mediating role of learned helplessness and the moderating role of social support. Front. Psychol. 15, 1329664. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1329664 (2024). Medline:38390420.

Zhou, M., Yu, K. & Wang, F. Cognitive flexibility and individual adaptability: A Cross-Lag bidirectional mediation model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 29, 182–186. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.01.037 (2021).

Katz, C. et al. Examining resilience among child protection professionals during COVID-19: A global comparison across 57 countries. Child Abuse Negl. ;106659. Medline:38326165 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.106659

Hoşgör, H. & Yaman, M. Investigation of the relationship between psychological resilience and job performance in Turkish nurses during the Covid-19 pandemic in terms of descriptive characteristics. J. Nurs. Manag. 30, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13477 (2022). Medline:34595787.

Huffman, E. M. et al. How resilient is your team? Exploring healthcare providers’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Surg. 221, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.09.005 (2021). Medline:32994041.

Yörük, S. & Güler, D. The relationship between psychological resilience, burnout, stress, and sociodemographic factors with depression in nurses and midwives during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr Care. 57, 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12659 (2021). Medline:33103773.

Creswell, K. G., Cheng, Y. & Levine, M. D. A test of the stress-buffering model of social support in smoking cessation: is the relationship between social support and time to relapse mediated by reduced withdrawal symptoms? Nicotine Tob. Res. 17, 566–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu192 (2015). Medline:25257978.

Ortiz-Calvo, E. et al. The role of social support and resilience in the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among healthcare workers in Spain. J. Psychiatr Res. 148, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.12.030 (2022). Medline:35124398.

Shi, L-S-B., Xu, R. H., Xia, Y., Chen, D-X. & Wang, D. The impact of COVID-19-Related work stress on the mental health of primary healthcare workers: the mediating effects of social support and resilience. Front. Psychol. 12, 800183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800183 (2021). Medline:35126252.

Labrague, L. J. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 29, 1893–1905. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13336 (2021). Medline:33843087.

Blanco-Donoso, L. M. et al. Job resources, fear of contagion, and secondary traumatic stress among nursing home workers in face of the COVID-19: the case of Spain. J. Appl. Gerontol. 40, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820964153 (2021). Medline:33025850.

Chew, Q. H. et al. Perceived stress, stigma, traumatic stress levels and coping responses amongst residents in training across multiple specialties during COVID-19 Pandemic-A longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 6572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186572 (2020). Medline:32916996.

Acknowledgements

We would like to appreciate all the participants who showed great patience in answering the questionnaires.

Funding

The research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (72274140) and Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Project (22YJAZH137).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CF and CL conceived and designed the study. CF, CL, XL, RW and JS collected data. CF and CL conducted data analysis. XL, RW, JS and ZC performed data visualization. CF and WY Write original draft, ZC and WY completed review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Medical Ethics Committee of Shandong second Medical University reviewed and approved the protocol of the study in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. (ref: 2021YX067). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, C., Li, C., Li, X. et al. The effect of Effort-Reward imbalance on job performance among primary healthcare professionals: the mediating roles of social support and resilience. Sci Rep 15, 20036 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05533-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05533-9