Abstract

In this study a methodological framework for enhancing the detection and interpretation of archaeological features through near-surface geophysical surveys, in particular Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and magnetic gradiometry (MAG) is presented. Consequently a combined approach based on spatial analysis techniques and Artificial Intelligence, specifically Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), is devised to support automatic feature enhancement and recognition. This method has been experienced using GPR and gradiometric surveys, performed in a use case inside the archaeological area of Grumentum (Southern Italy). The results highlight the effectiveness of this approach in improving the readability of complex and heterogeneous geophysical datasets and increase the reliability of archaeological interpretations and in identifying subsurface remains and facilitating their interpretation. It is expected that the approach herein proposed can be promptly generalized and applied to other application fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, remote sensing, particularly near-surface, are significantly advanced and more available for research in different application fields1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Near-surface techniques geophysical surveys refer to a range of geophysical prospection methods devised to study the Earth subsurface within a few tens of meters. They include electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), electromagnetic surveying, ground-penetrating radar (GPR), induced polarization, magnetic gradiometry (MAG) surveying, seismic refraction and reflection surveys. Recently, significant advancements have been achieved in both methodology (as for example high-resolution GPR systems with multi-channel arrays, drone magnetometry, and multi-channel ERT) and processing tools.

The non-destructivity nature of RS techniques makes them particularly suitable for different cultural heritage applications ranging from the discovery of buried archaeological remains10,11,12,13to the imaging of cracks and fractures in masonry structures14,15and decay patterns in frescoes16.

Despite their usefulness, there are still considerable challenges in fully utilizing these datasets. For instance, automating data processing is crucial in remote sensing and archaeological surveys, particularly given the difficulties associated with large-scale investigations. In the past, there have been attempts at automation, excluding Artificial Intelligence (AI)17,18,19followed by the use of machine learning and AI in early GPR applications20,21. In fact, AI can enhance and accelerate data processing, as well as improve target recognition, which is especially challenging in archaeology due to the typically subtle signals22 involved. Ancient buried artifacts often require investigations at varying spatial scales and depths, and they can be obscured by noise and contamination, with their appearance changing based on soil type and moisture conditions. This poses a major challenge, especially before archaeological excavations when it is crucial to detect and assess both the extent and depth of buried remains, that can require the collection and integration of multiple dataset23,24,25,26,27.

This paper proposes a novel approach, based on the combination of spatial analysis techniques and Artificial Intelligence, specifically Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), applied to GPR and MAG data, to:

-

(1)

enhance and facilitate the recognition of archaeological features;

-

(2)

characterize the state of conservation of the buried archaeological remains;

-

(3)

estimate the different depths of the archaeological features as well as the total depth of the excavation;

-

(4)

evaluate the proposed methodological approach qualitatively as enhancement tool.

The use case is the archaeological area of Grumentum in the Basilicata region (Southern Italy), selected because of the availability of sufficient information to understand the type of archaeological features expected.

The data used for the experiment is provided by GPR and MAG. Considering the typical archaeological features found underground, such as walls, ditches, and roads, as well as the relatively shallow depth (in this specific case study expected no more than two meters) and the required spatial resolution, the combination of georadar and MAG proves highly effective in identifying two common proxy indicators, related respectively to variations in dielectric properties and magnetic susceptibility.

Materials and methods

Study area: the Roman town of Grumentum

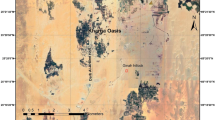

The test area selected for the investigation is located in the region of Basilicata (Fig. 1), specifically in the Grumento municipality, where there exists the ancient town of Grumentum that dates back to the pre-Roman and Roman eras28. This city holds particular significance during the Late Antiquity period and belonged to the ancient Lucania civilization. Grumentum is situated on an elevated terrain and is naturally protected on all sides by slopes formed by the actions of two rivers.

Geographical framing of the case study (a): Grumentum in the Basilicata Region (Southern Italy); (b) the investigated area. The acquisition direction for MAG and GPR is from NE to SE, x(m) while the acquisition progress is in NW direction y(m). Detailed outline of the GPR data acquisition scheme is in Fig. 2. Orthoimage in (b) provided by Regione Basilicata, Ortofoto 2013, available via WMS: http://rsdi.regione.basilicata.it/rbgeoserver2016/maps_orto2013/OI.OrthoimageCoverage/wms. License: IODL 2.0 (https://www.dati.gov.it/content/italian-open-data-license-v20). Image created with QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

The city’s urban design, which originated in the third century BC, takes the shape of an oval and is structured around three main parallel streets. These streets include the major thoroughfare known as the “decumanus maximus” and two lateral streets, intersected at right angles by smaller streets called “cardines.” The city was encircled by walls, featuring six gates, spanning a perimeter of approximately 3 km. The total area occupied by Grumentum encompassed about 25 hectares, although only a tenth of this has been excavated and revealed by archaeologists.

Grumentum remained an active settlement from the Republican era through the early Middle Ages, as evident from the transformations observed in its ancient topography. Archaeological layers dating from the 6th to the 8th or 9th centuries AD have been unearthed, along with Christian structures such as the churches of S. Marco, S. Laverio, and S. Maria Assunta.

In recent times, the church of S. Maria Assunta has undergone investigation as part of the Project Chora-Archaeological Laboratories in Basilicata. The project has involved research activities in the vicinity of the church. Within the framework of the Chora Project, the CNR-IBAM (today ISPC) of Potenza conducted comprehensive investigations utilizing geophysical and remote sensing techniques.

In 2006, Grumentum underwent geophysical testing, specifically using georadar and MAG methods although not in the same area as in this study29. These tests, carried out east of the Forum, revealed the existence of a decumanus, running approximately north-south. Along the eastern side of this road, a series of nearly modular, quadrangular buildings were identified30,31.

Further archaeological inquiries, developed within the Chora Project, have emerged concerning the northeastern part of the city, near the aforementioned church of S. Maria Assunta. These inquiries have prompted the need for further non-invasive investigations employing a combination of geophysical prospecting techniques (MAG and georadar), along with multispectral and thermal infrared imaging techniques based on Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). Among the available datasets, in this paper, only those relating to ground penetrating radar and geomagnetic investigations will be subject to analysis and integration.

Survey methodologies

Magnetic gradiometry30,31

MAG is a key and widely used geophysical method32 in non-destructive archaeological exploration. Its goal is to detect anomalies in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by subsoil layers and interactions with buried artifacts. The magnetic anomalies are linked to induced or remanent magnetism33. Induced magnetization is directly related to the strength of the ambient magnetic field and the material’s magnetic susceptibility, while remanent magnetism refers to the magnetism an object retains even without an external magnetic field. Both types are crucial in archaeology. Induced magnetization highlights variations in magnetic susceptibility between soil layers and rocks, helping identify features like ditches, pits, and other buried structures. Magnetic anomalies caused by these buried elements can range from a few nT for smaller remains to thousands of nT for burned structures or metal objects34. MAG is particularly valuable in archaeology due to its cost-effectiveness and speed compared to other methods like GPR and ERT, making it useful for both small site analysis35 and large-scale surveys36.

From the analysis of these anomalies referring to the layers of soil closest to the surface it is possible to identify the presence of buried elements of archaeological origin. In order for a significant change in magnetic measurements to be observed, there must be a corresponding contrast between the magnetic properties of the different buried archaeological elements and the soil surrounding them.

Archaeological features that exhibit significant contrasts in magnetic susceptibility—and are thus particularly suitable for magnetic prospection—include discrete elements such as wells, furnaces, and burial structures, as well as elongated features like ditches, roadways, and architectural remains.

In the archaeological site of Gumentum the MAG survey was carried out on the ground according to adjacent grids of size 40 × 40 and profile spacing every m, for a total surface area of approximately 8000 m2. It does not cover the same area with GPR. However more details about data acquisition and overlay between GPR and MAG are explained in Sect. 3.1.

The instrument used is the Bartington Grad601, a high-resolution fluxgate gradiometer equipped with a data logger and two Grad-01–1000 L sensors mounted on a rigid carrier bar. Calibration or adjustment is performed on-site to eliminate external influences such as field effects and diurnal variations, minimizing disturbances caused by acquisition conditions, including operator-related factors and the characteristics of the background environment where the data is collected.

The instrument in gradiometric configuration, made up of two sensors, each sensor contains two fluxgate magnetometers with one metre of vertical separation allows each reading of the Earth’s magnetic field to be sampled and recorded in rapid succession, using the difference between two readings, taken at two different sensor altitudes. The magnetic gradient is recorded along a series of lines spaced 1 m depending on the resolution required. Along the acquisition direction measurements are taken at intervals ranging from 0.125 m along each traverse, with the sensor positioned approximately 30–35 cm above the ground. The instrumental sensitivity is ± 1 nT (nano Tesla). The instrument allows you to record approximately 16.000 readings organized according to square meshes of 10, 20, 30 and 40 grid units. The data is then transferred to a personal computer via serial interface and managed with appropriate software.

Gradiometric measurements act as a “filter” by removing the effect of diurnal variations in Earth’s the magnetic field. This approach also automatically suppresses disturbances caused by regional magnetism, enabling the identification of objects with residual magnetization that exhibit an anomalous magnetic behavior compared to the surrounding terrain. The latter, in Grumentum, is characterized by alluvial fine to medium sediments, with a magnetic susceptibility ranging from 0.0001 to 0.01 SI units.

GPR survey

Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) is a non-invasive geophysical technique used in archaeology to identify and map underground structures, artifacts, and soil layers. It operates by emitting high-frequency electromagnetic waves into the ground and recording their reflections from subsurface features.

The transmitted signal, typically produced by a ground-coupled or air-launched antenna, interacts with these discontinuities, resulting in changes in wave propagation that are captured by a receiving antenna. Interpretation of these reflected signals allows researchers to infer the depth, shape, and composition of buried features. While the operating frequency of the antenna is a key parameter—lower frequencies generally provide greater penetration depth, and higher frequencies yield finer resolution—this relationship is influenced by several additional factors such as dielectric permittivity and electrical conductivity of the subsurface materials particularly the presence of moisture or clay, can significantly attenuate the signal and limit both resolution and depth.

GPR surveys in Grumentum were conducted using a RIS MF Hi-Mod GPR System from IDS, equipped with an array of two multi-frequency antennas operating at 200 MHz and 600 MHz. The 200 MHz and 600 MHz data were collected in continuous and reflection modes, with time windows of 130 ns and 160 ns, respectively. The scan samples were set to 512 with a resolution of 16 bits and a transmission rate of 100 kHz.

The GPR data acquisition grid was constructed according to two orthogonal directions: the first is the parallel acquisition direction with 81 profiles 40 m long (x) spaced 1 m apart; the second is the transverse direction, divided into two 40 m by 40 m square quadrants, each with 41 profiles, for a total length of 80 m (y) and a total of 163 profiles, again spaced 1 m apart (Fig. 2).

Detailed outline of the GPR data acquisition scheme. Image created with QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

The acquired data are subsequently processed using standard two-dimensional processing techniques using the GPR-Slice Version 7.0 software37. Processing includes:

-

(1)

Amplitude normalization (based on the mean amplitude of the entire profile) to prevent signal clipping, using polynomial interpolation.

-

(2)

Dewowing filter to remove low-frequency components.

-

(3)

Background removal by averaging and subtracting background noise.

-

(4)

Energy decay correction using a mean amplitude decay curve derived from all available traces.

-

(5)

Declipping to reduce excessively high amplitudes.

-

(6)

Bandpass filtering to minimize noise related to the applied gain function previously applied.

-

(7)

Kirchhoff 2D-velocity migration, using a velocity range of 0.060–0.065 m/ns (consistent with medium-low water content), performed by fitting diffraction hyperbolas using the hyperbola fitting tool in GPR-Slice, which allows manual adjustment of theoretical curves to match observed diffractions in the radargrams.

The best-fit velocity was then used to calculate depth from two-way travel time (TWT) using the formula (Eq. 1):

.

GPR depth estimation is performed by:

-

(i)

Hyperbola fitting: The initial step is to estimate the subsurface wave velocity by hyperbola fitting on the diffraction patterns. This provides a first approximation of depth, but requires validation.

-

(ii)

Depth slice selection: it involves algorithms of GPR slice software that analyze radargrams and identify changes in the reflection pattern that correspond to distinct subsurface depth slice.

These algorithms typically operate based on signal characteristics such as reflection amplitude, frequency, phase, or other characteristics of the GPR data. The migrated data is subsequently fused together into three-dimensional volumes and visualized in planes to improve spatial correlations of the anomalies of interest38.

The time slices obtained for the data measured at 200 MHz and 600 MHz respectively are shown in Figs. S1 and S2 of the Supplementary Material. Following the data processing described in this section, the final resolution of the data is 0.25 m.

Analytical methods

The two investigation methodologies, briefly described above, are used to acquire and analyze information content relating to two diverse proxy indicators of potential archaeological interest: (i) the different response speed of materials to electromagnetic waves (in the case of GPR), and (ii) the variations of magnetic field (in the case of the MAG method), produced by deposits, structures, materials of cultural interest.

The heterogeneity of GPR and MAG datasets and the consequent difficulty of integrating and/or merging them is linked not only to the different physical parameters involved, but also to the fact that in the first case three-dimensional information is obtained, in the second case the imaging results refer to a layer of unknown depth.

From what follows, the problem of integrating these two families of data is complex both due to the high dimensionality data analysis and to the need to create spatial relationships or groupings between entities that are as different (and distant) from each other as possible.

Therefore, the complex integration of the logic and functionality of artificial neural networks, specifically Self-Organizing Maps (SOM), with the spatial analysis technique of Local Spatial Autocorrelation (LISA), helps to gain a deeper understanding of the spatial structure of data.

Consequently, the originality of the approach followed consists not only in the application of SOM in multi-sensor dataset, but also in the combination of SOM and LISA, bridging the gap between classification and spatial methods and complementing each other. This with the aim to enhance pattern recognition by also considering spatial relationships in the dataset.

Self-organizing map (SOM)

SOM is a competitive type of artificial neural network belonging to Deep Learning methods introduced by Kohonen38. It is generally used to produce a low-dimensional representation of complex high dimensionality data, preserving their topological structure, and improving the identification of hidden patterns and clustering.

While there are numerous examples of SOM being used in the literature, there are few instances where it has been applied to geophysical datasets in the context of cultural heritage: SOM has been used for classifying GPR data for archaeological site detection39,40analyzing multi/hyper-spectral datasets for the restoration of paintings41or studying decay patterns of frescoes and architectural surfaces16,42.

SOM works as follows:

-

In the first phase (initialization), a certain number of nodes are initialised. They will constitute the lattice that represents the SOM. Each node will be associated with a cluster identified within the dataset through the process described in the next steps. as a result, the total number of nodes corresponds to the total number of clusters that will be identified in the entire dataset. These nodes, also called neurons, are randomly assigned a set of multidimensional weights, having the same number of dimensions as the input vector.

-

Then the node competition begin. Each element of the input vector is assigned to the node that best represents it, i.e. the one that is n-dimensionally closest to it, also referred to as the Best Matching Unit (BMU).

-

Finally there is a learning phases. As vectors are assigned to each node, these self-modify, so that they are increasingly representative of the vectors associated with it.

The output SOM is a bi-dimensional space, in our case constituted by a regular grid where each square is a SOM node, represented with its own color. The space between the cells of this grid where the grey shades represent the similarity level between near nodes. The cell color depends on the similarity of that neuron and all the pixels of the input data similar to that node will be classified with the same color. Consequently, all the pixels of the grid are classified according to their similarity to a given SOM node. For example, looking at the elaboration presented in this paper (Fig. 71) and in the Supplementary Material (Figs. S3-S26), on the right there is the SOM, with its 34 × 22 neurons (squares). Each neuron represents a cluster, which can also be seen in the image on the left, in which one can see where the elements, having the same colour, are clustered. The colouring of the SOM follows its own topology: similarity in colour and proximity between neurons indicates a quantitative proximity between clusters.

The primary reason SOM was chosen for this case study over other machine learning methods is its unsupervised nature. The second reason is its ability to handle unlabelled data. Supervised methods would need a substantial amount of labelled data, which is not available for an unexplored and unknown site. As for methods like Bayesian approaches, the specific conditions of the case study and the dataset’s diversity make it impossible to apply the required a priori assumptions for those models. Deep neural networks, while effective for classification, are computationally demanding even in small study areas and require a large labelled dataset for effective training.

The SOM’s capabilities are particularly well-suited for small study areas, like the one analyzed. However, its scalability for larger and more complex archaeological contexts presents a computational challenge, as it would demand more resources. Distributed computing frameworks can provide solutions for such issues.

Local indicator of spatial autocorrelation (LISA)

A phenomenon with a spatial component and its representation can be characterised by positive, negative or no spatial autocorrelation; this helps to understand if elements are distributed in a clustered, uniform or random way43. The spatial distribution of a variable can be analysed locally through many indicators, but in this paper we used the Local version of Moran’s I44,45 introduced by Anselin46 (Eq. 2):

.

where X marked is the mean intensity of all events, xi is the intensity of the i event, wij is a weight matrix that takes in count the distances between events and the values of their interactions. To define this weight matrix also the direction of the relative position between events and consequently the neighborhood considered (contiguity) in the analysis are important. According to this, some different type of contiguity can be defined: for example, in the rook contiguity elements are neighbor if they share an edge; in the queen contiguity two spatial units are considered neighbors if they share at least one vertex or one edge.

Si[2] is defined by Eq. 3:

,

where n is equal to the total number of features analyzed.

If I > 0 there is positive autocorrelation (the feature is part of a cluster): a feature has neighbors with similarly high or low attribute values.

If I < 0 near features are dissimilar, usually they are outliers.

Values tending toward or otherwise close to 0 characterize features with a random distribution.

Experimentation process description

To analyse the geophysical datasets, pre-processing and processing phases were going through, as follows:

Pre-processing phase:

-

a data preparation process was executed, in order to allow the dataset integration;

-

a first SOM was implemented in order to choose the best SOM dimension for the analysis;

-

after the previous step, the pattern of the ancient Roman road has emerged. The dataset was cleaned by it, because this allows the dataset to be lighter and quicker to be analysed, as well as obtaining clearer results that are less affected by noise.

Processing phase; SOM was performed to analyse the following datasets or groups of datasets:

-

MAG data,

-

GPR time slices at 200 MHz overlaid for the depth 0–3 m,

-

GPR time slices at 600 MHz overlaid for the depth 0–3 m,

-

combination of MAG and GPR data at 200 MHz until a depth of 1.5 m,

-

combination of MAG data and GPR data at 600 MHz until a depth of 1.5 m.

As regards the GPR data and their combination with MAG data, the SOM is applied to a three-dimensional input dataset, having two dimensions given by a pair of consecutive depth slices from the GPR data, and the third dimension consisting of the MAG data.

This was aimed as exploratory analysis, to understand at wich depth the archaeological features are intact and up to what depths they are present.

SOM was performed over the best groups of consequent depth slices of the same five categories of dataset analysed in point one. Here SOM was useful for its dimensionality reduction capabilities; consequently, it allowed us to find the GPR groups of time slices where the overall shape of the features is better preserved and to have a new raster analysable to extract the complete shape of the buried elements.

LISA was applied on the SOMs that synthesize the groups of time slices that are consecutive and contain the most representative clusters of archaeological features. The aim is to investigate similar elements and their spatial autocorrelation. In this phase, thus, LISA represents a sort of spatial filtering in the SOM’s results and would help to extract a hypothesis about the overall configuration of the buried site.

All the steps of this process are resumed in the flow chart in Fig. 3 and the results of each of them are descripted in the following paragraphs.

The workflow, especially with the use of SOM, enables significant automation in extracting archaeological patterns. However, both the pre-processing and the interpretation phases still require human involvement and evaluation. In the pre-processing phase, human intervention is needed for the data preparation, choosing the SOM dimension, and cleaning the dataset.

Results

Dataset Preparation

The integration of different sensors, as GPR and MAG ones, is not a trivial task, because they refer to physical parameters, moreover GPR provides three-dimensional information whereas gradiometry refers to a layer of unknown depth.

Furthermore, GPR and magnetic MAG have different georeferencing characteristics, with a different extent and a different cell size. So, data preparation is mainly about finding the perfect overlap of the different elements.

For what concerns the spatial extent choice, only the overlapping areas were considered.

As regards the homogenisation of cell size for data to analyse, it requires different steps.

Let us consider that the GPR dataset has a regular, squared-grid of points of acquisition with a dimension of 0.25 m. Instead, the gradiometric layer has a rectangular distance of data acquisition and, as a consequence, a rectangular grid size, where the measurement point interval along the profiles was chosen 0.25 m to adapt to the GPR data, and profile interval is 1 m obtained by dual sensors acquisition (Fig. 4).

To harmonize the two resolutions, an ordinary kriging and a consequent resample were used: the result is a radiometric grid with a cell size of 0.25 m as the GPR one (Fig. 5). The parameters inserted inside the Cross-validation was used to optimize and validate the obtained results. The mean and the mean standardized resulted equal to 0.003 and 0.0006; this shows the good balance in the estimation. The Root Mean Square equal to 2.7 (1% of the dataset values) and the Root Mean Square Standardized equal to 1.1 certify a good accuracy of the interpolation.

Kriging of gradiometric data: the cell size of this raster is equal to 0.25 m. Image created with QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

After the interpolation, the datasets for SOM analyses were created in the following way: the geometric feature is a pixel 0.25 × 0.25 m, while to each square is associated to different fields the gradiometric and the GPR values normalized (between 0 and 1), at the different depths. Altogether, we have a total of 158 dimensions: one containing the gradiometric datum, 77 dimension are constituted by the GPR 200 MHz depth slices, 77 dimension are constituted by the GPR 600 MHz depth slices (each field corresponding to a time slice, for a total depth of exploration of about 3 m) and finally, one for a numerical identifier of each element and two for the storage of x and y coordinates of the pixel’s centroid.

SOM initialization and dataset cleaning

For our work the software used to perform SOM is the V-Analytics47.

To begin with, as input data, the information related to gradiometric, GPR 200 and GPR 600 were inserted.

From this first elaboration, it is possible to emphasize a subsurface wall (in light orange in Fig. 6c, inside the black rectangle), to extract the road area present inside the study area corresponding to a Roman road (in red in Fig. 6c) and to choice the best SOM dimension for the following extractions. The road, when extracted, was deleted by the original dataset to simplify the number of clusters present in the analysed map and to lighten the dataset by reducing the pixel number. As mentioned in Sect. 2.3.1, in the first step, it is necessary to introduce the number of nodes constituting the SOM. Consequently, in order to choose the size of the SOM, different values were entered iteratively, starting from the size of the SOM suggested by the software (135 × 90 nodes), but then ultimately comparing the results obtained from the following subdivisions: (1) 34 × 22, (2) 17 × 11, (3) 8 × 5 The SOM with 8 × 5 elements (Fig. 6c) optimizes the road extraction. Instead, regarding the emphasis and extraction of the archaeological elements, the line definition is maintained until the 34 × 22 SOM-sized (Fig. 6a); in the 17 × 11 SOM (Fig. 6b), for example, the same line starts to lose definition, and it is composed by less clustered elements. Moreover, computation time is much reduced in the SOM 34 × 22 (Fig. 6a) compared to larger SOMs. Consequently, this was chosen as the dimension for our experimentation.

First SOMs processing for clean the road pattern and the cell choice. Results obtained with (a) 34 × 22, (b) 17 × 11, (c) 8 × 5 cell-sized SOM. Image created with QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

In SOM also other parameters are important, such as the learning rate and the neighbourhood radius are important. In this work, we have adopted a heuristic approach, based fundamentally on knowledge of the data and carrying out some tests by iteratively varying the values for the search radius and the learning rate, even if this do not have any significant changes for the case study.

Results from SOM applied to gradiometric data

The first SOM analysis was conducted by considering only the gradiometric data and their spatial distribution. Figure 7 shows how the pixels were associated to the SOM neurons.

On the left you can view the gradiometric data reclassified through the SOM. On the right there is the corresponding output SOM. The colors of each node of this correspond to the colors of each class. Image created with V-Analytics (http://geoanalytics.net/V-Analytics/).

The result is very fragmented, probably due to the effect of ploughing on the ground covering the features of archaeological interest.

Results of SOM applied to GPR 200 mhz and GPR 600 mhz

After MAG data, SOM analysis was conducted by considering GPR 200 MHz first and GPR 600 MHz after. For both the datasets, we have measurements made by GPR at 77 depth slices. Between each measurement, there is a depth slice of 3.89 cm about, for a total depth of 3 m.

We ran the SOM using pairs of two consecutive time slices as input data (depth slices 1 and 2, depth slices 3 and 4 and so on). All the fields were standardized to homogenize the values. We found what is described below.

For what concerns GPR 200 MHz results, (all the processed pairs are in the Appendix, from fig. S.3 to fig. S.10) the SOM emphasizes linear features that are evident in the following processing:

-

1.

depth slices 1–2, 3–4 and 5–6 even if from 3 to 6.

-

2.

depth slices 13–14, 15–16 and 17–18 with a different angle than features highlighted in depth slices 3–4 and 5–6.

-

3.

depth slices 21–22 and 23–24, in the same direction as described in point 2.

-

4.

depth slices 51 to 64, in the same direction as the features in point one, although they gradually disappear, until the pair 73 to 74, from which there is only noise.

In all the other depth slices no significant patterns are evident. Regarding GPR 600 MHz results (all the processed pairs are in the Appendix, from fig. S.11 to fig. S.18), the significant patterns are from depth slice 27, up to depth slices 31 to 38.

The SOM analysis revealed linear features of archaeological significance at depths ranging from approximately 0.7 to 1.5 m. Further anomalies appear in slices 51 to 64, which correspond to depths between 2 and 2.5 m. Consequently, the results suggest that the excavation should extend to a maximum depth of around 2.5 m.

After these considerations, the following groups with adjacent depths were grouped for a new SOM analysis (see Sect. 3.5) to be combined with the gradiometric data. More specifically:

-

For GPR 200 MHz the depth slices 13–18, 21–24, were analysed.

-

For GPR 600 MHz the depth slices 29–30, 31–34, 35–38 were analysed.

Results of SOM applied to the combination of gradiometric data with GPR 200 mhz and 600 mhz data

To combine MAG data with GPR 200 MHz and 600 MHz data, only the first 40th fields were processed for GPR data, to consider only approximately the first 1.5 m, distance within the MAG data are reliable.

For what concerns the results obtained by the combination of MAG and GPR 200 MHz data (results in Appendix, from fig. S.19 to fig. S.22), in general, there is a deterioration in the visibility and in the extraction of buried features; the most relevant results are in the following layers elements:

-

1.

combination of MAG and time slices from 13 to 18 of GPR 200 MHz;

-

2.

combination of MAG and time slices from 21 to 24 of GPR 200 MHz.

For what concerns the results obtained from the combination of MAG and GPR 600 MHz data (results in Appendix, from Fig. S.23 to Fig. S.26), also, in this case, the feature enhancement is deteriorated compared to the only GPR results. However, the groups of depth slices that allows to see buried elements are:

-

1.

combination already obtaining of MAG and GPR 600 MHz depth slices 29 to 30;

-

2.

combination of MAG and GPR 600 MHz depth slices 31 to 34.

LISA filtering results

After analysing with SOM GPR and GPR with MAG data, the results were further processed using LISA to impose a spatial filter.

However, the values assigned by the SOM cannot be directly used in LISA. First, the identifiers assigned by the SOM are numeric and correspond the specific column and row of each cell. Second, the arrangement of these cells within the SOM is not random, but follows a topology that reflects the similarity between the clustered values. For this reason, the following method was adopted to transform the categorical identifiers into a suitable format for LISA. The number of row identifiers in the SOM used ranges from 1 to 22, and the number of columns from 1 to 34. Consequently, the output raster will have an identifier in each pixel expressed as column_row.

To convert this, we multiply the number of columns by 100 and add the row number to the result. We thus obtain a numeric variable that still reflects the quantitative proximity expressed by the SOM topology and can be used as intensity within LISA (Fig. 8).

Moreover, the Queen contiguity was used as input parameter because it makes the analysis more flexible and sensitive to both edge and corner relationships, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of spatial patterns in the data.

Results of the best depth slice groups are shown in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12. In these:

Comparison between results obtained with SOM groups of GPR200MHz depth slices (Ds) (a,b) and after the post-processing of SOM with the LISA index (c,d). Image created with QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

Comparison between results obtained with SOM groups of GPR200MHz depth slices (a,b) and MAG data and after the post-processing of SOM with the LISA index (c,d). Image created with QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

-

1.

The red and blue classes represent two types of clusters, and therefore two neuronal groups, respectively. More specifically, red can be associated with the best-preserved elements and stone material in the immediate vicinity, whereas blue can be associated with homogenous soil.

-

2.

The yellow and cyan elements, present in very small quantities, are neuronal groups with negative spatial autocorrelation. They do not correspond to any particular feature, just some noise.

-

3.

The grey elements are characterized by no autocorrelation (i.e. classified by neurons with different intensities at varying spatial distances) and mainly distributed at the borders of the red and blue areas. This suggests that they could be areas adjacent to the walls, with stone elements and fragments of various sizes resulting from the breaking of walls. These grey areas appear strongest in the upper left part of the images, where the plough marks are strongest.

For what concerns the GPR 200 MHz data, the best feature extraction was obtained for depth slices 13–18 and 21–24 (Figs. 9 and 10).

Whereas, the GPR 600 MHz data exhibit the best enhancement of features between 29 and 30, 31–34 and 35–38. (Figures 11 and 12) These groups, although consecutive, were analysed separately because they show a reversal of GPR values from low to high and consequently autocorrelation will vary from low to high. A similar effect occurs in the combination of MAG and GPR 600 MHz data, where the best feature extraction was obtained for depth slices 29–30 and 31–34.

Even if the best group of depth slices of the two datasets are different, they were all analysed with LISA for a better comparison (Figs. 9 and 10).

Discussion

In this paper, the effectiveness of the approaches based on SOM and LISA has been evaluated by comparing the results obtained using SOM and LISA between each other and geophysical maps (GPR at different depths and MAG). The comparative analysis between the results of the SOM and the geophysical investigations is essentially based on identifying patterns of archaeological interest, which, in the case of Grumentum are linked to wall structures of a Roman insula.

To better resume and discuss the final assessment found after the results presented in the previous paragraph, the comparison between three sectors named A, B and C is shown.

Focusing on the comparison between SOM (Fig. 13d-g) and LISA (Fig. 13h-m), the best results could be observed from SOM-based results which enhance GPR features of potential archaeological interest. They are liner features reasonably referable to the presence of buried walls or wall foundations.

GPR time slices at 1.0 m acquired at 600 MHz an and 200 frequency, respectively (a,b), Gradiometric map (c), maps resulting from SOM applied to GPR time slices at 1.0 m acquired at 600 MHz and 200 MHz frequency respectively (d,f), maps resulting from SOM applied to MAG and GPR time slices at 1.0 m acquired at 600 MHz and 200 MHz frequency, respectively (e,g) and finally maps resulting from Moran LISA applied to SOM (h–k). Software used: GPR Slice (a,b), Surfer (c), QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org (d–k); image composition GIMP2.10.32 (https://www.gimp.org/).

Despite the limited contribution of LISA in improving the visibility of archaeological features, its informative contribution is nevertheless significant. In fact, it allows to extract a useful feature vector to hypothesize the overall configuration of the buried site as explained in Sect. 3.6 and to quantify its extent and geometries as reported in Sect. 3.7. This is neither possible with the source data, nor with the SOM result, which still has too many unambiguous features that offer good visual enhancement, but do not allow the overall configuration to be extracted directly.

Moving the comparison to geophysical maps (GPR and MAG; see Fig. 13a-c)) and to SOM based results (see Fig. 13d-g), the archeological interpretation in a comparative way has been performed by ten experts including one in remote sensing, one in GIS, three in remote sensing applied to archaeology, two archaeologists, and three geologists, including two experts in geophysics applied to archaeology.

The ten experts have been asked to compare in three sectors, named A, B, and C, the visibility of the features (FV) observable from GPR, MAG and SOM applied to GPR and GPR along with MAG. In particular, the experts have been asked to analyze the quality and the quantity of the features observed. The three sectors (A, B, and C) were chosen because they are enough spaced from each other and exhibit a different visibility of the features from geophysical maps. The results obtained are summarized in Table 1.

In particular, comparing MAG with GPR at 200 and 600 MHz, we can observe better results in terms of feature visibility from GPR at 200 MHz respect to GPR at 600 MHz and to MAG map (2.5, 1.86, and 1.4, respectively, as maximum values (FVmax); 1.93, 0.71, 0.58, as FVmin, respectively; 2.25, 1.18, and 0.88, respectively, as average values). Considering the same dataset (MAG or GPR) the best results could be observed in sector C, with respect to sectors A and B.

These results show a greater capability of GPR (at depth of one meter) than MAG in highlighting anomalies of potential archaeological interest, typically referable to the presence of masonry structures in the subsoil. The fact that at 200 MHz the results exhibited are better than those obtained at a frequency of 600 MHz, should reasonably indicate that the reflectors, potentially referable to masonry structures, would extend in depth well over one meter.

Moving to the comparison between geophysical maps (GPR, MAG) and SOM, the comparative archaeological interpretation put in evidence a significant enhancement contribution in emphasizing the visibility of geophysical based features of archaeological interest, including the MAG one.

Starting from the average value of 1.18 computed for GPR acquired at 600 MHz, SOM enables to improve the visibility of features (as shown in Table 1) evaluated as 1,81 and 2,26, respectively for SOM applied to GPR and to GPR along with MAG, respectively.

As regards the GPR acquired at 200 MHz, only SOM applied to GPR (and not GPR along with MAG) improved the visibility of features which have been evaluated as 2,42, with respect to 2,25 of GPR.

SOM from GPR 600 MhZ and MAG provide better results than those obtained only using GPR 600 MhZ; whereas SOM applied to GPR 200 MhZ provides better results compared to SOM applied to GPR 200 MhZ and MAG.

The comparison between the geophysical datasets with the SOM results highlights some morphological and dimensional differences between the corresponding features. Figure 14a shows a detail of a GPR time slice at a depth of 1.30 m acquired at 600 MHz and the relative SOM result. The GPR map shows linear features with less wide respect to the corresponding SOM-based features. In some parts, GPR-based features exhibit a less ‘chromatic continuity’, because of non-homogeneous radar reflection. Focusing on the linear features numbered from 1 to 5, it is possible to observe a better visibility (or continuity) of the features detectable from SOM based map with respect to the GPR map. On five features, three (2, 3, and 5) are less clear on the GPR map with respect to SOM one. Moreover, SOM map enhances the presence of irregular shape features which could refer to inconsistent stone material resulting from the degradation of wall structures. This inconsistent stone material could be the reason for the greater width of the linear features as highlighted in Fig. 14b.

Detail of the comparison between 600 MHz GPR time slice at 1.30 m and result from SOM (a) and enlargement of the red rectangle area (b) with respectively the GPR time slice at the top and the SOM at the bottom. Image created with GPR Slice and GIMP2.10.32 (https://www.gimp.org/).

To verify this hypothesis, the GPR, SOM and LISA maps were compared with the radargrams, to analyze each reflection in detail (Fig. 15a–d, f).

GPR map at 200 MHz (a) and the relative SOM-based (d) and LISA result (f), along with two radar profiles (b, c) crossing a number of linear features referable to buried walls, (e) Reconstructive hypotheses of the reflectors. Software used: GPR Slice (a–c), QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024): QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.34.3). QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org (d–f), 3D generated with Autodesk CAD 3D (e).

The radar profiles reveal nine local reflectors (labelled as w10 to w18 in Fig. 15b,c), representing the responses of GPR electromagnetic waves to different buried materials and their varying state of integrity. Three distinct behavioral patterns are observed.

-

1)

Well-preserved walls some reflectors are well focused (Fig. 15bc w10, w14, w16-w18), exhibiting a pattern of that is clearly represented in Fig. 15e-top. These reflectors correspond to well-preserved wall. This interpretation is supported by the analysis carried out with the SOM, which shows a prevalence of similarly colored pixels in the burgundy range (Fig. 15d). This is even more evident in the results obtained with LISA (Fig. 15f), where the reflector is almost entirely filled with elements classified as high-high. This indicates both quantitative clustering (reflecting the good state of conservation and the compactness of the wall element) and spatially clustering (confirming the same wall structure).

-

2)

Partially degraded walls one reflector (Fig. 15bc w11) is accompanied by subtle reflections on both sides, suggesting that it corresponds to the structure depicted in Fig. 15e (middle). This feature represents a wall with inconsistent stone material along its sides, likely resulting from structural collapse and subsequent erosion. In the SOM-classified image (Fig. 15d) this area contains not only pixels in the burgundy range but also multiple colors, indicating material variability. The LISA analysis (Fig. 15f) further supports this interpretation, as the area displays a combination of red pixels (intact portions of the wall) and gray pixels, which indicate a loss of autocorrelation due to material inhomogeneity and greater heterogeneity in the geophysical signal.

-

3)

Inconsistent stone material the radar profile exhibits the presence of less localized reflections (Fig. 15bc w12-13-15, reasonably referable to inconsistent stone material, placed in some cases on underlying wall structures (Fig. 15e-bottom). The SOM raster (Fig. 15d) in this area displays a mixture of colors, reflecting the material’s heterogeneity. This translates into a predominance of gray areas in the LISA analysis (Fig. 15f), indicating a lack of autocorrelation due to the highly inhomogeneous nature of the material and the resulting signal variability.

Finally, for what concerns depth estimation, the SOM of GPR time slices enable the estimation of a maximum depth of approximately 2.50 m, as shown in Figures S.13–S.16 in the Supplementary Material. Figure 15 presents an example that includes a GPR map acquired at 200 MHz. (Fig. 15a) and the corresponding SOM-based map (Fig. 15d), both highlighting features at a depth of about 1.3 m, as confirmed by the radargram in Fig. 15b.

Conclusion

Today’s near-surface geophysics data are significantly advanced and more available for research in different application fields, among which the archaeological site and feature detection. In the field of archaeology, near-surface geophysics data offer a great potential allowing noninvasive investigations to assess the presence of subsurface archaeological remains as well as their extent in space, depth and state of preservation.

However, archaeology is one of the most challenging fields of application being that the result depends on many factors linked both to the characteristics and dimensions of the target as well as to the properties and conditions (moisture content, vegetation coverage) of the soil during the data acquisition. These challenges can be addressed using multiple geophysical techniques and appropriately integrating diverse data. Hence the need to develop effective methodologies for the processing, integration, and interpretation of heterogeneous data sets to facilitate the extraction of suitable and reliable information.

In this paper a combined approach based on Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) and spatial analysis techniques is proposed and discussed. The test selected for the experimentation is the Roman archaeological site of Grumentum (Southern Italy) investigated using the integration of GPR and gradiometric data.

For what concerns the methodology, the use of SOM has demonstrated a significant ability to improve the visibility of archaeological features, while the use of LISA allowed us to enhance the best conserved part of the archaeological site.

Regarding SOM, its application to GPR 600 MhZ and gradiometric data provide better results than those obtained only using GPR 600 MhZ data; whereas SOM applied to GPR 200 MhZ data provides better results compared to SOM applied to GPR 200 MhZ and gradiometric data.

The limitations of the SOM-based approach stem from the inherent challenges posed by the nature of archaeological sites, the complexity of subsurface structures, and the uncertainties associated with geophysical methods.

Specifically, radar waves are influenced by the material’s dielectric properties, meaning that variations in soil moisture, mineral composition, and density can significantly impact the results. Additionally, the different materials found in archaeological features can reflect radar waves in varying ways, complicating their identification.

Magnetic gradiometry, in this case, yields lower-quality results in terms of feature visibility compared to GPR.

The limitations of both magnetic and ground-penetrating radar make the SOM approach particularly suited to enhance subtle archaeological features.

Finally, the further enhancement of the extension of the wall structures was possible thanks to the combined use of SOM and LISA, which allowed us to define hypothesis related to the overall configuration of the buried site.

As a whole, output from our analyses highlighted the potential of the devised method to enhance and detect subtle features as those related to buried archaeological remains and improve the analysis of subsurface layers. It is expected that the approach herein proposed can be applied to other and deeper archaeological targets (for example ditches and pits), and sensor combinations taking into account site-specific complexities.

Further steps will include in the methodology the uncertainty quantification, field validation, and the automatic selection of the best elements.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

22 December 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the Acknowledgements section was incomplete. The Acknowledgements section now reads: The scientific activities related to the post-processing and Self-Organizing Map (SOM)-based applications of geophysical data were supported by the CHANGES Project, funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment Line 1.3 — Extended Partnerships (Spoke 5, Work Package 3). We acknowledge the Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage of Basilicata of Ministry of Culture for the authorization (DG-ABAP del MIC, n. 1011 del 20/09/2021) and the Chora Project on the behalf of the Basilicata Region Authority for the archaeological investigations led by Francesca Sogliani. The original article has been corrected.

References

Anderson, K. & Gaston, K. J. Lightweight unmanned aerial vehicles will revolutionize Spatial ecology. Front. Ecol. Envir. 11, 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1890/120150 (2013).

Behroozmand, A. A., Keating, K. & Auken, E. A. Review of the principles and applications of the NMR technique for Near-Surface characterization. Surv. Geophys. 36, 27–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-014-9304-0 (2015).

Dal Moro, G. Surface Wave Analysis for Near Surface Applications (Elsevier Inc., 2014).

Iglhaut, J. et al. Structure from motion photogrammetry in forestry: a review. Curr. Rep. 5, 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-019-00094-3 (2019).

Luhmann, T. Close range photogrammetry for industrial applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 65, 558–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2010.06.003 (2010).

Nguyen, F., Garambois, S., Jongmans, D., Pirard, E. & Loke, M. H. Image processing of 2D resistivity data for imaging faults. J. Appl. Geophys. 57, 260–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2005.02.001 (2005).

Pánek, T. & Klimeš, J. Temporal behavior of deep-seated gravitational slope deformations: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 156, 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.02.007 (2016).

Qin, R., Tian, J. & Reinartz, P. 3D change detection – Approaches and applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 122, 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2016.09.013 (2016).

Robinson, D. A. et al. Advancing process-based watershed hydrological research using near-surface geophysics: A vision for, and review of, electrical and magnetic geophysical methods. Hydrol. Processes. 22, 3604–3635. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.6963 (2008).

Catapano, I. et al. Full three-dimensional imaging via ground penetrating radar: assessment in controlled conditions and on field for archaeological prospecting. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 115, 1415–1422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-013-8053-0 (2014).

Masini, N. et al. Towards an operational use of geophysics for archaeology in Henan (China): methodological approach and results in Kaifeng. Remote Sens. 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9080809 (2017).

Masini, N. & Lasaponara, R. in Sensing the Past: From artifact to historical site (eds Nicola Masini & Francesco Soldovieri) 23–60 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Persico, R. Introduction to Ground Penetrating Radar: Inverse Scattering and Data Processing 9781118305003 (2014).

Leucci, G., Masini, N. & Persico, R. Time–frequency analysis of GPR data to investigate the damage of monumental buildings. J. Geophys. Eng. 9, 81–S91. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-2132/9/4/S81 (2012).

Leucci, G., Persico, R. & Soldovieri, F. Detection of fractures from GPR data: the case history of the Cathedral of Otranto. J. Geophys. Eng. 4, 452–461. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-2132/4/4/011 (2007).

Danese, M., Sileo, M. & Masini, N. Geophysical methods and Spatial information for the analysis of decaying frescoes. Surv. Geophys. 39, 1149–1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-018-9484-0 (2018).

Leckebusch, J., Weibel, A. & Bühler, F. Semi-automatic feature extraction from GPR data for archaeology. Near Surf. Geophys. 6, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2007033 (2008).

Linford, N. & Linford, P. in AP: 12th International Conference of Archaeological Prospection 12th–16th September 2017 138–139 (University of Bradford, 2017).

Pregesbauer, M., Trinks, I. & Neubauer, W. An object oriented approach to automatic classification of archaeological features in magnetic prospection data. Near Surf. Geophys. 12, 651–656. https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2014014 (2014).

Küçükdemirci, M. & Sarris, A. G. P. R. Data processing and interpretation based on artificial intelligence approaches: future perspectives for archaeological prospection. Remote Sens. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14143377 (2022).

Manataki, M., Papadopoulos, N., Schetakis, N. & Di Iorio, A. Exploring deep learning models on GPR data: A comparative study of AlexNet and VGG on a dataset from archaeological sites. Remote Sens. 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15123193 (2023).

Yu, S. & Ma, J. Deep learning for geophysics: Current and future trends. Rev. Geophys. 59 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021RG000742 (2021).

Kvamme, K. L. Integrating multidimensional geophysical data. Archaeol. Prospection. 13, 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/arp.268 (2006).

Ernenwein, E. G. Integration of multidimensional archaeogeophysical data using supervised and unsupervised classification. Near Surf. Geophys. 7, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2009004 (2009).

Papadopulos, N., Manataki, M. & Kalayci, T. in 43rd Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology.

Küçükdemirci, M., Özer, E., Piro, S., Baydemir, N. & Zamuner, D. An application of integration approaches for archaeo-geophysical data: case study from Aizanoi. Archaeol. Prospection. 25, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/arp.1583 (2018).

Piro, S., Mauriello, P. & Cammarano, F. Quantitative integration of geophysical methods for archaeological prospection. Archaeol. Prospection. 7, 203–213 (2000).

Mastrocinque, A., Marchetti, C. M. & Scavone, R. Grumentum and Roman cities in southern Italy = Grumentum e le città romane nell’Italia meridionale. ix, 369 pages: illustrations (some color), maps (some color) ; 30 cm (BAR Publishing, 2016).

Mastrocinque, A. Grumentum romana: convegno di studi, Grumento Nova, Potenza : salone del Castello Sanseverino, 28–29 giugno 2008 / a cura di Attilio Mastrocinque (Moliterno: V. Porfidio, 2009).

Bavusi, M., Chianese, D., Giano, S. I. & Mucciarelli, M. Multidisciplinary investigations on the Roman aqueduct of grumentum (Basilicata, Southern Italy). Ann. Geophys. 47, 1791–1801 (2004).

Chianese, D., D’Emilio, M., Bavusi, M., Lapenna, V. & Macchiato, M. Magnetic and ground probing radar measurements for soil pollution mapping in the industrial area of Val Basento (Basilicata region, Southern Italy): a case study. Environ. Geol. 49, 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-005-0082-3 (2006).

Larson, D. O., Lipo, C. P. & Ambos, E. L. Application of advanced geophysical methods and engineering principles in an emerging scientific archaeology. First Break. 21, 51–52 (2003).

Aspinall, A., Gaffney, C. & Schmidt, A. Magnetometry for Archaeologists. Geophysical Methods for Archaeology 189–201 (Altamira, 2008).

Piro, S., Sambuelli, L., Godio, A. & Taormina, R. in Near Surf. Geophysics 6 405–414 .

Aitken, M. J. A., R. Magnetic prospecting. Antiquity 32, 270–271 (1958).

Keay, S. J., Parcak, S. H. & Strutt, K. D. High resolution space and ground-based remote sensing and implications for landscape archaeology: the case from portus, Italy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 52, 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.08.010 (2014).

Goodman, D. & Piro, S. GPR Remote Sensing in Archaeology (2013).

Kohonen, T. Self-organizing Maps (Springer, 1997).

Spanoudakis, N. S. & Vafidis, A. in Near Surface 2008–14th European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics.

Vafidis, A., Economou, N., Spanoudakis, N. S., Hamdan, H. A. & Niniou-Kindeli, V. in Near Surface 2007–13th European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics.

Palleschi, V., Marras, L. & Turchetti, M. A. Interesting features finder: A new approach to multispectral image analysis. Heritage 5, 4089–4099. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040211 (2022).

Danese, M., Demšar, U., Masini, N. & Charlton, M. Investigating material decay of historic buildings using visual analytics with multi-temporal infrared thermographic data. Archaeometry 52, 482–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2009.00485.x (2010).

Getis, A. in Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications (eds Manfred M. Fischer & Arthur Getis) 255–278 (Springer, 2010).

Moran, P. A. J. B. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. 37, 17–23 (1950).

Moran, P. A. P. The interpretation of statistical maps. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 10, 243–251 (1948).

Anselin, L. Local indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geographical Anal. 27, 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x (1995).

Andrienko, N., Andrienko, G. & Gatalsky, P. in Proceedings of the working conference on Advanced visual interfaces 217–220 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2000).

Acknowledgements

The scientific activities related to the post-processing and Self-Organizing Map (SOM)-based applications of geophysical data were supported by the CHANGES Project, funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment Line 1.3 — Extended Partnerships (Spoke 5, Work Package 3). We acknowledge the Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage of Basilicata of Ministry of Culture for the authorization (DG-ABAP del MIC, n. 1011 del 20/09/2021) and the Chora Project on the behalf of the Basilicata Region Authority for the archaeological investigations led by Francesca Sogliani.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Maria Danese and Nicola Masini; data survey and data curation, Nicodemo Abate, Marilisa Biscione, Francesca Sogliani, Maria Sileo, Pepe Laviero; methodology, Maria Danese; validation: all the authors; writing—original draft preparation, Maria Danese, Maria Sileo, Nicola Masini; writing—review and editing, all the authors.; visualization, Maria Danese; supervision: Maria Danese, Rosa Lasaponara, Nicola Masini, Francesca Sogliani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Danese, M., Sogliani, F., Sileo, M. et al. AI methods for enhancing and recognizing archaeological features in heterogeneous geophysical datasets. Sci Rep 15, 32742 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05539-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05539-3