Abstract

The intensification of human activity, industrialization and urbanization has increased the risk of pollution due to large quantities of waste rich in heavy metals. Objective of this study was to assess the mitigating effects of biochar derived from açaí seeds on the biometric and physiological responses of Virola surinamensis plants grown in soil contaminated with cadmium. Seedlings of V. surinamensis grown in soils contaminated with varying doses of Cd (0, 10, 20, and 30 mg L-1) and different biochar proportions (0%, 5%, and 10%). Statistical analysis was performed using the multivariate exploratory principal components and the F-test, and when significant, the Tukey test was applied, and. At a dose of 10 mg L-1 of Cd, the number of leaves was higher in the absence of biochar; however, this did not differ significantly from the treatment with 5% biochar, which was more effective in maintaining chlorophyll a content in the presence of Cd. Furthermore, for plants exposed to 10 and 20 mg L-1 of Cd, the inclusion of 5% biochar mitigated the toxic effects of the metal, leading to increased rates of photosynthesis. Plants treated with 20 mg L-1 of Cd also presented higher transpiration rates with 5% biochar application. For intercellular CO2 concentrations, soils contaminated with 10 mg L-1 of Cd demonstrated an increase in carbon concentration when treated with biochar. Thus, the addition of 5% biochar was effective in attenuating cadmium toxicity, suggesting its potential as a mitigation strategy for contaminated soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intensification of human activity, industrial activities and urbanization has increased the risk of pollution due to heavy metals alone. For example, mining produces large quantities of waste rich in heavy metals, such as cadmium, lead and zinc, in addition to destroying the vegetation cover of the area to be used, aggravating soil degradation, promoting water and wind erosion and leaching of pollutants into the groundwater, triggering a progressive degree of contamination of other areas1.

There are some bioremediation methods that are economically viable, environmentally friendly, and highly applicable2. Phytoremediation, for example, is one of the methods that can absorb metal compounds from the soil, such as cadmium, through special natural or deliberately bred plants using their roots to remove or reduce their bioavailability3,4. Phytoremediation includes plant extraction, plant stabilization, plant filtration, and plant stimulation5.

Phytoremediation of Cd-contaminated soil is a common method of Cd reduction. Hyperaccumulator plants generally have well-developed roots with the ability to adsorb high levels of heavy metals present in the soil and transfer them to above-ground parts6,7. To date, five species of Cd hyperaccumulator plants with high Cd detoxification capacity have been found. The Cd doses in their leaf tissue is generally greater than 300 µg g − 1 dry weight8.

Therefore, the use of plants in soil decontamination allows the valorization and conservation of species, for example Virola surinamensis (Rol. ex Rottb.) Warb plants, popularly known as ucuúba, an endangered forest species that grows relatively quickly, high biomass production, widely distributed and adapted to floodplain and igapó ecosystems in the Amazon, especially in estuaries. This Amazonian species has favorable characteristics as it is susceptible to contamination and important receptors for nutrients, organic and inorganic contaminants, including heavy metals. Therefore, it must have a certain tolerance to these metals, including cadmium and aluminum9.

V. surinamensis (Rol. ex Rottb.) Warb is a forest species with economic and medicinal interest, in addition to being useful for the restoration of altered areas. It is a widely distributed species and adapted to floodplain and igapó ecosystems in the Amazon10. These ecosystems are constantly susceptible to contamination by heavy metals11, indicating that the plant has strategies to tolerate environments contaminated by heavy metals.

The V. surinamensis plants has been the subject of studies as a way to conserve the native species and use it in degraded areas, seeking to evaluate its remedial potential by aiding in the decontamination of soils, including those contaminated with heavy metals, ensuring a balanced and sustainable environment. Furthermore, the research can serve as a basis for practical applications, whether industrial or agricultural, that seek to solve problems with waste or even ensure the income of traditional communities that depend on the resources offered by the species.

Among heavy metals, cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic transition metal at very low exposure levels and has acute and chronic effects on the health of plants, animals, humans and all living beings. As a consequence of industrial activity and anthropogenic activity, it is estimated that 30.000 tons of Cd are released into the environment each year12. Cadmium is not degradable, so it persists in the environment once released. This property, together with its high mobility, bioaccumulative power and toxicity at very low concentrations, such as 0.003 mg L−1, make it one of the most important heavy metals13.

This metal is recognized as one of the most toxic and inhibitory of physiological processes in plants. Studies in several crops have shown that it reduces growth, photosynthetic activity, transpiration and chlorophyll content11,14,15,16. Furthermore, it causes chlorosis, oxidative stress, nutritional imbalances and modifies the activity of enzymes involved in the metabolism of organic acids and the Krebs cycle17,18,19,20.

In the Amazon, work with sustainable alternatives is being developed in favor of the reuse of waste, as is the case with the production of biochar from Euterpe oleraceae Mart. (açaí) seeds. Biochar is a vegetable charcoal resulting from the pyrolysis process, capable of improving soil properties, water retention, preventing soil degradation and losses, increasing the content and sequestration of nutrients in the soil, mitigating the impact of potentially harmful substances toxic, promote the well-being of soil organisms; improve plant growth and biomass production and quality21,22.

Soil application of biochar-based composts can play a considerable role in environmental management and pollution reduction from multimetal-contaminated soils23. Several studies have shown that biochar can potentially act as a soil pH regulator, carbon sink, and soil particle binder, as well as help stabilize long-term heavy metals in polluted soils24. In the latter case, the biochar in soils contaminated can promote the immobilization of metals, causing less absorption and phytotoxicity to plants25,26,27. According to Wang et al.28, biochar can reduce the mobility of metals in soils through the processes of ion exchange, specific adsorption and complexationm improving the sorption capacity of the soil, the immobilization of the metal and, consequently, delaying the absorption of the metal by plants28,29,30.

Biochar has a direct influence on the bioavailability of compounds due to complexation, adsorption and precipitation processes, provided by its physicochemical characteristics (pH, ash, organic components and its porous structure) that help in the unavailability of contaminants31,32,33. However, despite the promising results on the biochar pyrolysis process and its influence on soil fertility and physical properties34,35, research on its applicability as a plant remediator and attenuator, as well as its stability and regeneration in soils contaminated by heavy metals, requires further investigation in the Amazon region.

Considering the tolerance of V. surinamensis to cadmium, the high mobility of this metal and the potential of biochar in mitigating contaminated soils, we tested the hypothesis that açaí seed biochar influences the biometric and physiological characteristics of V. surinamensis plants exposed to areas contaminated by Cd. Therefore, the objective of this work was to evaluate the mitigating effect of Euterpe oleraceae Mart. seed biochar on the biometric and physiological responses of Virola surinamensis plants subjected to doses of cadmium.

Material and methods

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse belonging to the Institute of Agricultural Sciences (ICA), of the Federal Rural University of the Amazon (UFRA) – Belém (PA), with geographic coordinates of 01º 27′ 21"S, 48º 30′ 16"W and average altitude of 10 m. The local climate is classified as Af, according to the Köppen classification, with an average annual rainfall of 3000 mm, an average temperature of 27 °C, an average humidity of 85% and high cloud cover throughout the year36. Controlling these variables is essential for plant development, maintaining the physiological activities of seedlings and protecting them against disease and pest attacks, in addition to preserving soil moisture and dynamics.

Soil collection and preparation

Soil collection was carried out in a native forest area located inside UFRA, in the 0–20 cm depth layer, as it is the soil layer where the largest volume of roots of most cultivated plants is concentrated, we therefore seek to identify which nutrients are most available in the soil and whether they are in adequate concentrations for the plant used in this work37.

The soil was collected, dried in the open air, sieved through a 2 mm mesh and homogenized. During collection, a composite sample was taken for chemical characterization38 and granulometric analysis39, which was subjected to soil analysis in the IBRA laboratory – Instituto Brasileiro de Análises, located in São Paulo. The results of these analyzes are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

After soil analysis, acidity correction was carried out using the base saturation method (V%) of soil, using 9.7 g of dolomitic limestone per pot (PRNT 97.4%) with the objective of reaching at least 50% base saturation as an indication of fertile soil, providing the necessary nutrients to the seedlings during the execution of the experiment. In addition to neutralizing, the soil acidity through the incorporation and reaction of calcium and magnesium for 30 days.

During this period, the soil remained in hermetically sealed plastic bags and inside the pots, where it was stirred every two days in order to homogenize the action of the limestone in the soil.

Soil fertilization

After collection, the fertilization was carried out per pot according to the needs of the species and the chemical analysis of the soil in the EMBRAPA Recommendation Manual (2020). Macronutrients (166.66 mg of nitrogen, 170.45 mg of phosphorus and 0.103 mg of potassium) were used in the form of urea (45%), triple superphosphate and potassium chloride (52%); For micronutrients, fertilization was carried out for copper and manganese (8.40 mg of copper and 46.30 mg of manganese), as they presented low levels in the soil analysis, in the form of copper sulfate and manganese sulfate, respectively.

Seedlings production

For the present work, V. surinamensis seedlings were used. These seedlings were produced from the germination of homogeneous and visibly healthy seeds, collected in March 2023 from mother trees located in the UFRA native forest area. In this process, polyethylene bags measuring 10 cm wide by 18 cm long were used, filled with soil collected in the 0–20 cm depth layer, where they remained in the nursery for 6 months due to their slow growth, characteristic of a late secondary or climax species, between the months of March to September 2023, being irrigated manually twice a day maintaining soil moisture.

After germination and development of the seedlings, 48 with uniform heights of approximately 20–30 cm, and healthy seedlings without the presence of visible deformations or pest attacks were selected to be used in the experiment.

Soil exposure to cadmium chloride (CdCl2.H2O)

After the limestone reaction period, 3 kg of soil apparent density of 2.63 g cm−3 was placed according to the pot’s capacity (3 dm3). Contamination of the material occurred manually with the help of a beaker, where the solution was gradually placed in the soil at different doses of cadmium (Cd) (0, 10, 20 and 30 mg L−1 of solution), in the form of cadmium chloride (CdCl2.H2O), considering agricultural, residential and industrial research reference values of 3, 8 and 20 mg L−1, respectively, presented in CONAMA resolution nº. 420 of December 28, 2009.

Production, characterization and application of biochar

To produce biochar, açaí seeds were used, an agro-industrial material considered a residual byproduct of the açaí pulping process. The raw material was collected in local açaí beaters establishments, in the municipality of Belém, State of Pará. After collection, the seeds were washed in running water and dried in an oven at 70 ºC for 24 h to ensure that the residues were completely dry. After drying, samples of 400 g of açaí seeds were prepared wrapped in aluminum foil and placed in a NOVUS – N1030 muffle oven with a heating time of 10 °C per minute, where they remained for 1 h at 600ºC34, for the thermochemical conversion of biomass through the pyrolysis process. After this process, the size of the biochar particles was standardized using an electric mill and a sieve with a 2 mm mesh.

To characterize the biochar, all analyzes were carried out in triplicate, and the mean and standard deviation of the results obtained were calculated. The hydrogen potential (pH), specific surface area (SSA) and water retention capacity (WRC) followed the EMBRAPA methodology (2017).

From the immediate chemical analysis of the biochar produced, it was possible to determine the moisture (M), volatile material (VM), ashes (ASH) and fixed carbon (FC) (Table 3), following the methodology proposed in the ASTM standard D1762-8440.

The production of acai seed biochar and its application to the soil can improve aeration porosity, aggregate stability, and the proportion of soil macroaggregates. When biochar is produced at high temperatures, such as 600 and 700 ºC, a material with high pH, greater recalcitrance, and greater potential for water retention in the soil is obtained, due to its hydrophilic character34,35 and specific surface area.

Incorporation of biochar into the soil

Ater correction and exposure of cadmium in the soil, the incorporation of biochar into the soil was carried out per pot, where it remained incubated for 60 days in different proportions, 0%, 5% and 10%, referring to the pot’s capacity of 3 kg of soil, corresponding to 0 g, 150 g and 300 g, respectively.

According to the pre-defined biochar proportions, were the same ones used by Kul et al.41 as soil mitigator, the material was weighed and incorporated manually with the help of a tray where charcoal and soil were mixed until a homogeneous and uniform mixture was obtained. At this stage, the turning was disregarded, because the improvements in soil quality resulting from biochar were affected by the soil disintegration process42.

Experimental design

The experimental design used was randomized blocks in a 4 × 3 factorial scheme, with four replications, totaling 48 experimental units. This factorial consisted of twelve treatments, with factor A corresponding to doses of Cd, one of them being the control treatment (without Cd), and the others with three doses of Cd (10 mg, 20 mg and 30 mg L−1); and factor B corresponds to the three proportions of biochar (0%, 5% and 10%).

Biometrical variables

The measurement of biometric parameters was carried out upon removal from the experiment, 75 days after transplanting, when the plants showed visible symptoms of toxicity. Data were obtained on the following variables: aerial part height (H) measuring from the base to the stem apex, diameter at stem height (DSH), number of leaves (NL) and root length (RL).

The DSH was measured with the aid of a Digimess digital caliper, the length of the aerial part and the root were evaluated using a millimeter ruler, and the number of leaves per plant was calculated manually.

These variables are essential to monitor the development and growth of seedlings, seeking to analyze their behavior in contaminated soil and with biochar, and whether they are influenced by the different materials. Therefore, the plant material used in this study was identified by forestry engineers, researchers who are members of the Study Group on Biodiversity of Higher Plants. It is worth remembering that there were no voucher specimens of this material deposited in a publicly accessible herbarium.

Photosynthetic pigments and gas exchange

Photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a, b and total) were determined in the leaf of the middle third of the plants in each experimental unit, with the aid of a digital chlorophyllometer ClorofiLOG model CFL 2060, brand Falker, in the morning between 09:00 and 10:00 h. The results obtained from the equipment are expressed as Falker Index (IF).

For gas exchange measurements, measurements were taken one day before removal from the experiment on expanded leaves in good phytosanitary condition, between 9:00 and 11:00 h, representing the daytime period of maximum photosynthesis. For measurement, a leaf from the middle third was selected in all experimental units of each treatment, using one block of plants at a time.

Each leaf was inserted and positioned in the median leaf region, inside the IRGA chamber, a photosynthesis meter, model LI-6400XT from LI-COR, Inc. Lincoln, coupled with a 2 × 3 cm leaf chamber (Li6400-40) in concentration of CO2 of 400 µmol−1 with an artificial light source with a flow of 1000 µmol photons m−2 s−1, to determine the net CO2 assimilation rate (A) (µmol CO2 m−2 s−1), stomatal conductance (gs) (mol H2O m−2 s−1), transpiration (E) (mmol H2O m−2 s−1), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) (µmol CO2 molar−1) and internal/external carbon ratio (Ci/Ca).

All variables mentioned had unique measurements on the day before the experiment was removed, individually and by seedlings, including all repetitions of treatments organized in randomized blocks.

Statistical analysis

For comparative purposes, the data obtained were subjected to analysis of variance using the F test using the statistical program AgroEstat version 5.4, and when significant, the means were compared using the Tukey test at a 5% probability level43. To verify the normality and homoscedasticity of data distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk test and the Bartlett test were performed, respectively. The mean values presented are followed by the standard error.

The data were also subjected to multivariate exploratory principal components and classification analysis using the hierarchical method and principal components performed in the program STATISTICA 7.0 (StatSoft. Inc., Tulsa, OK, EUA).

Results

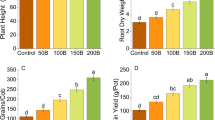

Among the variables analyzed and presented in Table 4, there was a significant interaction between the doses of Cd and the proportions of biochar for the number of leaves (p < 0.05), chlorophyll a (p < 0.05), chlorophyll b (p < 0.01), total chlorophyll (p < 0.01), photosynthesis (p < 0.01), stomatal conductance (p < 0.01), transpiration (E) (p < 0.05), internal carbon (Ci) (p < 0.05) and relationship between the internal and external proportion of CO2 (p < 0.01). For the root length variable, there was a significant isolated effect only for the biochar proportions (p < 0.01).

Biometrical variables

The NL in V. surinamensis plants was influenced by the interaction of biochar and Cd. In the absence of metal, plants subjected to 5% biochar showed higher NL (24 leaves), representing an increase of 52% (15.75 leaves). At a dose of 10 mg L−1 of Cd, the NL was higher when biochar was not applied, however it did not differ from the treatment with 5%. For the other doses of Cd (20 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd) there was no significant difference for NL in relation to the different proportions of biochar (5% and 10%). Likewise, plants subjected to different doses of metal, without biochar, managed to maintain NL, becoming tolerant to the effects of the metal (Fig. 1A).

Number of leaves (NL) and root length (RL) (cm) in V. surinamensis plants exposed to different Cd doses and biochar proportions. Means followed by the same lowercase letter do not differ by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) between Cd doses in the same proportion of biochar, and means followed by the same capital letter do not differ by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) between the proportions of biochar at the same dose of Cd.

The RL of V. surinamensis plants showed a significant difference only for plants subjected to different proportions of biochar. The exposure of plants to charcoal, when compared to control (21.58 cm), provided an increase of 29.42% (27.93 cm) and 17.19% (25.29 cm) for RL in proportions of 5% and 10% biochar, respectively (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the effect of biochar in its highest proportion (10%) may have caused toxicity to the plants, affecting the length of the roots, which is why there was a 17.19% reduction in this treatment.

Pigments

For the Chl a index, plants without Cd did not show a significant difference in Chl a, when exposed to different proportions of biochar. Likewise, plants exposed only to doses of the metal also showed the same behavior, characterizing a certain tolerance to the effect of Cd. However, the addition of biochar together with the doses of Cd significantly influenced the variable under analysis. In the presence of different doses of metal, 5% biochar was the proportion that managed to maintain the Chl a index in the plants. However, the 10% proportion reduced the amount of chlorophyll by 22.40%, 17.72% and 30.29% for doses of 10 mg L−1, 20 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd, respectively, showing a significant difference for the highest dose (30 mg L−1 of Cd). Therefore, this proportion was not able to maintain or increase chlorophyll at this dose of Cd (Fig. 2A).

Chlorophyll a (Chl a), b (Chl b) and total (Índice Falker—IF) in V. surinamensis plants exposed to different Cd doses and biochar proportions. Means followed by the same lowercase letter do not differ by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) between Cd doses in the same proportion of biochar, and means followed by the same capital letter do not differ by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) between the proportions of biochar at the same dose of Cd.

The Chl b index was lower in relation to Chl a. Plants subjected to metal-free treatments showed a significant difference in relation to the proportion of biochar, where plants exposed to 5% had a reduction of 28% (11.8) in Chl b, while the proportion of 10% biochar caused a 6% increase (17.96) in chlorophyll. At dosages of 10 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1, there was a significant difference when 10% biochar was applied, promoting a reduction in the chlorophyll index of 39.74% (11.07) and 55.09% (6.79), respectively. On the other hand, it was observed in plants with 20 mg L−1 of Cd that the proportions of biochar improved the chlorophyll index by 106.10% (14.57) and 153.20% (17.90) in plants with 5% and 10% biochar, respectively (Fig. 2B).

For total chl, there was no significant difference for plants exposed to different proportions of biochar and no metal. In treatments with 10 mg L−1 of Cd, the proportion of 10% biochar had a toxic effect on plants, reducing total chl by 27.11% (40.27). For plants exposed to 20 mg L−1 of Cd, plants without biochar were affected by the metal, on the other hand, charcoal became effective in its different proportions, increasing by 44.65% (49.57) and 42.57% (48.86) the chlorophyll index referring to 5% and 10% biochar, respectively. At a dosage of 30 mg L−1 of Cd, the plants showed similar behavior to those treated with 10 mg L−1, where the toxic effect of biochar (10%) also reduced the chlorophyll index (31.02%—33.02) (Fig. 2C).

Gas exchange

Analyzing A, there was a significant difference between plants exposed to different proportions of biochar and without metal, where 10% biochar provided an increase of 76% (5.24 μmol m−2 s−1) in A. Plants subjected to 10 mg L−1 and 20 mg L−1 of Cd showed a significant difference between treatments with biochar, demonstrating similar behavior in plants with 5% biochar, mitigating the effect of the metal on the plant and increasing A by 256.71% (10 0.63) and 349.33% (10.02), respectively. The plants treated with 30 mg L−1 of Cd, when exposed to 5% biochar, were able to statistically maintain the A rate in the plants (Fig. 3A).

Photosynthesis (A), stomacal conductance (gs), transpiration (E), internal carbon (Ci) and Internal carbon and carbon relationship (Ci/Ca) in V. surinamensis plants exposed to different Cd doses and biochar proportions. Means followed by the same lowercase letter do not differ by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) between Cd doses in the same proportion of biochar, and means followed by the same capital letter do not differ by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) between the proportions of biochar at the same dose of Cd.

Analyzing the gs of V. surinamensis plants exposed to soils not contaminated by metal, 5% biochar provided an increase of 120% (0.11 mol m−2 s−1) in conductance. Plants that received treatments with 10 mg L−1 of 5% Cd and 10% biochar showed an increase in gas of 66.67% (0.10 mol m−2 s−1) and 33.33% (0.08 mol m−2 s−1), respectively. In soil conditions contaminated with 20 mg L−1 of Cd, the addition of 5% biochar statistically maintained the conductance in plants, minimizing the possible toxic effects of the metal. This does not occur in the proportion of 10%, reducing this conductance to 72.73% (0.03 mol m−2 s−1). Plants subjected to 30 mg L−1 of Cd showed similar behavior when exposed to 10% biochar, thus maintaining plant gas at the maximum dose of the metal used in this study. While plants at the same dosage, but with 5% biochar, were unable to achieve the same result, presenting a reduction of 44.44% (0.05 mol m−2 s−1) caused by factors that may have inhibited stomatal activity (Fig. 3B).

In treatments without metal, the proportion of 5% biochar provided an increase of 22.47% (2.18 mmol m−2 s−1) in the E rate of plants, in contrast, when exposed to 10% biochar, there was a reduction of 45.50% (0.97 mmol m−2 s−1) where the largest proportion may have had a toxic effect on the plants. This same behavior was observed in plants treated with 20 mg L−1 of Cd in different proportions of biochar. Plants exposed to doses of 10 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd did not show a significant difference in the E rate when biochar was incorporated. Likewise, the different doses of metal did not statistically influence the E rate in plants that did not receive biochar, presenting a potential tolerance of the species in relation to the metal (Fig. 3C).

In metal-free treatments, the proportion of 5% biochar provided an increase of 27.64% (263.20 μmol mol−1) in the Ci of plants, on the other hand, when exposed to 10% biochar there was a reduction of 22.69% (159.41 μmol mol−1), where the greater proportion of charcoal may have had a toxic effect on plants, as was also observed in E. V. surinamensis plants exposed to soils contaminated with 10 mg L−1 showed a significant difference for Ci, where the proportions of biochar managed to increase the carbon rate by 43.27% (185.75 μmol mol−1) and 61.97% (210.00 μmol mol−1) to 5% and 10% biochar, having a more representative effect in the largest proportion under study. However, plants subjected to doses of 20 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd showed a certain reduction in Ci of 23.78% (182.72 μmol mol−1) and 27.78% (172.75 μmol mol−1); 33.52% (130.54 μmol mol−1) and 67.83% (63.17 μmol mol−1), respectively, caused by the different proportions of biochar. With this, we can observe that at these dosages, the V. surinamenses plants managed to maintain the carbon rate in the absence of biochar, being the highest found among the treatments (Fig. 3D).

The Ci/Ca ratio showed significant differences in plants exposed to different proportions of biochar and without metal. In this condition, the proportion of 5% biochar caused an increase in the Ci/Ca ratio (16.92%—0.76 mol mol−1), while the highest proportion (10%) may have had a toxic effect on the plants, promoting a reduction of 38.46% (0.40 mol mol−1), as was also observed in E. In the presence of the metal, the plants presented different behavior and the proportion of 10% biochar presented better results than the proportion of 5%. Plants exposed to 10 mg L−1 of Cd, regardless of the proportion of biochar, did not present statistical difference in the Ci/Ca ratio when compared to the control (0% biochar). When plants were subjected to soils contaminated with 20 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd, the 5% proportion reduced the Ci/Ca ratio to 36.76% (0.43 mol mol−1) and 17.65% (0.56 mol mol−1), respectively. However, the 10% biochar proportion was able to improve the activity of enzymes involved in CO2 fixation, resulting in high Ci/Ca values of plants exposed to 30 mg L−1 of Cd, representing an increase of 26.92% (0.66 mol mol−1) (Fig. 3E).

The results of the principal component analysis generated for V. surinamensis plants with different proportions of biochar and cadmium dosages show an interrelation, explaining 60.28% of the total data variability. PC1 presented the highest percentage of variance, with 42.30%, while PC2, with 17.98%, obtained the lowest percentage of variance. In PC1, the variables height, Chl a, Chl b and Chl total presented positive loadings of 0.78, 0.91, 0.95, and 0.96, respectively, characterizing a direct correlation between the photosynthetic pigments. On the other hand, RL, gs, E, Ci, and Ci/Ca presented negative correlation in PC1, with values of 0.30, 0.72, 0.57, 0.19, and 0.80, respectively.

In PC2, only the variables Chl a and Ci/Ca presented positive loadings of 0.04 and 0.25, respectively. The other variables presented negative correlation in PC2, mainly D, H, NL, A, gs, E, and Ci, with values of 0.81, 0.39, 0.66, 0.33, 0.57, 0.49, and 0.38, respectively. Furthermore, the biplot graph corroborates that the Cd30B5 (30 mg L−1 of Cd and 5% biochar) treatment presented a higher correlation estimate, contrasting with Cd30B10 (30 mg L−1 of Cd and 10% biochar), which presents a lower correlation estimate, between the variables Chl a, Chl b, total Chl and A, where the presence of 10% biochar was not efficient in mitigating the toxic effect on plants, confirming the hypothesis of this study (Fig. 4).

Principal component analysis of biometric and physiological parameters of V. surinamensis plants exposed to different Cd doses and biochar proportions. (NL)—number of leaves; (RL)—root length; (Chl a)—chlorophyll a; (Chl b)—chlorophyll b; (Chl t)—chlorophyll total; (A) – photosynthesis; (gs)—stomacal conductance; (E) – transpiration; (Ci) internal carbon; (Ci/Ca) internal carbon and carbon relationship; Cd0, Cd10, Cd20 and Cd30 represent the doses of cadmium; and Bc0, Bc5 and Bc10 represent the proportions of biochar.

Discussion

Among the biometric variables, the leaf was the main organ affected by Cd toxicity with 10 mg L−1 as seen in Fig. 1, since dosages higher than 5 mg L−1 can cause this toxicity, especially in young leaves due to its tendency to accumulate greater amounts of this metal44,45,46.

In this sense, the different proportions of biochar (5% and 10%) in Cd-contaminated soils managed to maintain NL in V. surinamensis plants, especially in treatments in which 20 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of the metal were used, as shown in Fig. 1, because despite its toxicity, biochar tends to reduce the availability of metalloids47,48 maintaining the biometric development of plants. Furthermore, studies carried out by Andrade Júnior10 consider the species as tolerant to Cd, due to its ability to extract and accumulate metal in the root, restricting its transport to the aerial part, which could compromise the leaves by expressing its possible toxic effects.

For RL, the different proportions of biochar provided better root development by promoting nutrient absorption by plants, further minimizing the inhibitory effect of Cd stress49 on cell division and root elongation rate cells which can be caused by irreversible cell obstruction50. However, some studies have shown that the cell wall can also increase plant tolerance to Cd by preventing the metal from entering root cells6,51,52 through pectin, which is the main component of the cell wall that binds heavy metals51,53,54.

The application of biochar can increase the cation exchange capacity of the soil to retain and exchange these cations, thus increasing the availability of nutrients for plants55. With these benefits, consequently, biochar can improve soil fertility and reduce the availability of cadmium, thus improving soil, root growth and the rate of nutrient uptake of plants56, trying to maintain the biometric characteristics of plants.

Therefore, biochar may have influenced the absorption of essential nutrients and water for plant growth, as it has an alkaline pH, an ASE of 340 m2 g−1, a RWC of 2.5 g g−1, Cz content of 98.4% and CF of 1.1% as shown in Table 1, improving the chemical, physical and biological characteristics of the soil. In addition to these characteristics, there are studies that show biochar as a beneficial product for the morphological development of the root, including an increase in root volume, surface area and root density, to acquire more nutrients and water to improve photosynthesis57,58, corroborating the results found in this work.

Furthermore, biochar has a strong binding effect on free Cd in the soil, being able to reduce the absorption of Cd by plants, its effective content in the soil, and consequently, minimize its stress effect on plant growth2, allowing the permanence of plant species in areas contaminated by heavy metals, as is the case of V. surinamensis, and can be used as an alternative in the recovery of these degraded areas.

Chl a is the most abundant pigment and plays a fundamental role in photosynthesis58,59. Its content is considered an indicator of damage to the photosynthetic system induced by environmental stressors such as heavy metals60, but even with 10 and 20 mg L−1 of Cd, Chl a in V. surinamensis plants showed some tolerance to the metal, whether without or with 5% biochar.

On the other hand, plants subjected to 30 mg L−1 of Cd, biochar (10%) were unable to maintain the Chl a content, reducing it as shown in Fig. 2A, since chloroplasts are the primary sites of action of the Cd and consequently, affect the biosynthesis of photosynthetic pigments, resulting in chlorosis, which appears as the most common symptom of metal toxicity47. Therefore, the results found for chlorophyll characterize the maximum dose of Cd as toxic, where the proportion of 10% biochar, as it is a material that provides essential micronutrients and macronutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, potassium and zinc) to the soil61, may have provided an increase in nitrogen absorption, inducing a reduction in the enzymatic activity of chlorophyllase, and consequently, in the chlorophyll content62.

In Cd-contaminated soils, plants suffer abiotic stress and under this condition synthesize significantly less chlorophyll. This reduction in chlorophyll content leads to disturbances in the photosynthetic system and therefore chlorophyll is a suitable indicator of plant health decline63,64,65.

For Chl b, dosages of 10 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd did not statistically affect pigment production even without or with 5% biochar, since the plants showed a certain tolerance to the metal, guaranteeing the best Chl b index under these conditions (Fig. 2B). This proportion of biochar can alleviate the toxic effects of Cd stress on plant cells, protect the chloroplast structure of leaves, and increase the content of photosynthetic pigments2. Therefore, high levels of Chl b positively characterize the adaptability of the species due to the efficiency of photosystem II in carrying out photosynthesis59.

The incorporation of 5% biochar in soils contaminated with metal also provided the best total chl rate, due to the results of Chl a and Chl b, mitigating the toxic effect of the metal on V. surinamensis plants, with no significant difference between the different doses of Cd. Because the small particles of biochar improve its adsorption capacity due to the availability of additional sites effective in the adsorption of heavy metals, such as Cd66.

The total chl of plants subjected to doses of Cd and 10% biochar was lower when compared to 5% biochar as shown in Fig. 2C. This reduction can cause adverse effects on the photosynthetic system of V. surinamensis plants, affecting biosynthesis and the synthesis of complexes made up of chlorophyll, such as iron and zinc67. This micronutrient deficiency can also be caused by Cd toxicity, due to the ability to disaggregate chlorophyll-protein complexes that are combined or replaced by newly formed Cd-chlorophyll complexes. Therefore, the condition of the plant under stress reduces the expression of the iron citrate transporter in the xylem parenchyma cells, interrupting the flow of iron to the shoots68.

Therefore, the higher proportion of biochar (10%) may have caused toxicity to the plants’ photosynthetic pigments, as its high ASE may have limited the release of nutrients to the plants, making it slower, causing them to become more adsorbed on the biochar surface.

The mitigating efficiency of biochar in photosynthetic activity is well known. Despite being a process highly sensitive to heavy metals46, charcoal at a proportion of 5% managed to maintain and improve A’s performance due to its ability to capture and store carbon69. This directly influences plant growth due to its relationship with the carbon cycle, and when absorbed, it is stored and incorporated into the plant structure, integrating organic compounds70.

Studies conducted by Ali et al.3 state that the addition of biochar improves the accumulation of nitrogen in the soil and its content in the leaves, increasing the photosynthetic rate. This occurs due to the improvement in the physicochemical properties of the soil, which ultimately increases the accumulation of nitrogen and, consequently, the photosynthetic activity58,71,72.

Although the condition of the sandy clay soil together with biochar may have a slow release of nutrients, those that were released during the plant’s stay in the soil were sufficient to absorb water and nutrients that improved the photosynthetic apparatus. Possibly the amount of chlorophyll present in this plant was sufficient to absorb light and carry out the photosynthetic process properly.

On the other hand, increasing the proportion of biochar (10%) did not present the same result, since charcoal was unable to mitigate the toxic effects of Cd, considered an effective inhibitor of A73 which may have limited nitrogen accumulation by immobilizing it in V. surinamensis plants due to the high C/N ratio seen in Fig. 3A74. Its pode action includes disruption of chloroplast ultrastructure, inhibition of Calvin cycle enzymes, chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduction in CO2 assimilation due to stomatal closure36,75,76,77.

Even under toxic conditions (10 and 20 mg L−1 of Cd), V. surinamensis plants were able to maintain their gs when exposed to 5% biochar. Thus, the reduction of gs would result in low mesophilic conductance to CO2 and consequently in lower chloroplast CO2, justifying the decrease in photosynthesis in V. surinamensis, found in the research carried out by Andrade Júnior10. However, for 30 mg L−1 of Cd, this proportion was not effective, reducing the conductance caused by the plant’s contact with Cd, and the metal, upon entering the guard cells, is responsible for closing the stomata45,78, then stomatal resistance increases17 as a tolerance strategy to reduce the absorption of heavy metals from the soil, their accumulation and their phytotoxic effects10.

These factors allow it to maintain its physiological activities, since biochar, even at the maximum proportion used in this study (10%), will not always be able to maintain or improve the gs of plants subjected to different dosages, as seen in Fig. 3B at 20 mg L−1 of Cd. It is also worth mentioning that this efficiency can be influenced by the metal due to its mobility, as is the case with Cd, used in the research by Nogueira et al.79 with Schizolobium amazonicum Huber (Paricá), a forest species sensitive to applied doses of cadmium, interfering with gas exchange and plant growth.

In soils contaminated with 10 mg L−1 and 30 mg L−1 of Cd, plants were able to maintain their E rate, even when exposed to 5% or 10% biochar. This did not occur with plants exposed to 20 mg L−1 of Cd with 10% biochar, showing a reduction in E due to the ability of the metal to minimize the partial pressure of CO2 in the stomata, and consequently, in the gs80 of V. surinamensis plants. This reduction is caused by the effect of Cd in compromising the water status and altering the permeability of the plasma membrane81 of plant tissues in plants under stress conditions, which induces cellular vacuolization, narrowing of the intracellular space, reduction in the number of chloroplasts and increase in cell size, limiting water content and gs82.

Taking Ci into account, different doses of Cd reduced the carbon content when plants were exposed to 5% biochar. Since charcoal was unable to minimize the toxic effects of the metal, there was a reduction in the electron transport capacity in the leaves, and consequently, in the assimilation of Ci, which is possibly associated with damage to the thylakoids83 replacing compounds from the chlorophyll metabolic pathway84,85.

However, the stomatal opening can reverse this situation by contributing to the entry of CO2 into the mesophyll of the leaves, increasing the internal proportion of this gas, which may have happened in plants treated with 10 mg L−1 of Cd and 10% of biochar observed in Fig. 3D, causing an increase in transpiration67.

Taking into account the Ci/Ca ratio in V. surinamensis plants, this variable was more efficient when there was the incorporation of 10% of biochar in soils, demonstrating greater CO2 fixation. This may be the result of biochar’s ability to bind to heavy metals due to its adsorbent properties, reducing their availability and mobility in the soil50,86, otherwise they would be more accessible and easily transported within cells, damaging this relationship. of CO2.

Furthermore, açaí seed biochar is capable of assisting these gas exchanges with the environment (A, E and gs) without compromising the Ci/Ca concentration87, presenting good adsorption capacity for several heavy metal ions3,88. Thus, its chemical or physical activation significantly increases the adsorption capacity for heavy metals89, such as Cd, limiting its translocation to plant organs and its effects on metabolic pathways, which may have stimulated the occurrence of the Calvin Cycle, for example, increasing the activity of Rubisco, and consequently, the carbon fixation capacity90.

The incorporation of biochar minimizes the availability, accumulation, and toxicity of Cd in plants91,92, avoiding disruptions in the metabolic pathways of plants. And when combined with fertilization, Ahmad et al.93 and Dharma-Wardana94 state that essential plant nutrients have direct and indirect effects on these Cd conditions. For example, nutrients can minimize the solubility of the metal in the soil, facilitating several mechanisms, including: Cd sequestration in vegetative parts, adsorption and precipitation, competition between plant nutrients and metal for the same membrane transporter, and preventing metal accumulation in seeds. Likewise, indirectly, these nutrients can promote Cd dilution, relieving plant physiological stress and improving its productivity95.

It is worth remembering that plants also have defense mechanisms in response to abiotic stress conditions, reducing the accumulation of metal in plant cells and tissues due to the low intake and deposition of these elements in the roots, even though they are the first organ of the plant to come into contact with the metal96,97,98, making them the most effective preventive form in the absorption of heavy metals by plants68.

According to the biplot graph presented, resulting from the analysis of the principal components, the variables photosynthetic pigments, gs and Ci/Ca stood out due to their correlation and functionality in the presence of Cd and biochar, especially when the proportion of 5% can mitigate the effect of metal toxicity, associated with the potential of the species to tolerate soils contaminated with Cd, as seen in the study carried out by Andrade Júnior10. Plants can increase soil pH through their root exudates that bind to metals and precipitate them in the apoplast, blocking their entry into the cell99, which may have ensured the greatest production of photosynthesis, reaffirming the results of Fig. 3A in accordance with Fig. 4, allowing their development in environments contaminated by Cd, until further work can be developed with other heavy metals.

Conclusion

The use of biochar helped the biometric and physiological development of Virola surinamensis (Rol.) Warb plants exposed to cadmium. However, analyzing the set of variables under study, despite the proportion of 10% biochar having presented a toxic effect on total Chl, A and Ci/Ca at 30 mg L−1 of cadmium, and maintaining some results found for NF, RL, E and gs at 5% biochar, mainly at the doses of 10 and 30 mg L−1 of cadmium, this proportion (5%) was more efficient in attenuating the toxic effect of the metal and managed to maintain or improve the behavior of the plants subjected to cadmium. Therefore, the use of 5% biochar is considered recommended for mitigating soils contaminated by cadmium, however, field studies must be carried out to validate the efficiency of biochar at this proportion.

In the principal component analysis, it was found that Cd negatively affects the biometric and physiological characteristics of V. surinamensis plants, mainly chlorophyll production and photosynthetic activity. In addition, it is possible to corroborate the hypothesis under study, that biochar helps to reduce the toxic effects of the metal, mainly in the proportion of 5%, since the 10% biochar did not present the same expected effects, although some variables showed a positive response.

In addition, the behavior and importance of V. surinamensis plants in timber, medicinal and industrial applications make it a potential species for studies on soil remediation and recovery of degraded areas, leading to the search for new research to be carried out using 5% biochar or even different biochars. This bioproduct used in this work ensures the importance of reusing waste and applying it to the soil as a mitigating factor, bringing environmental, social and economic gains that involve agricultural practices, economic dynamics and an effect on climate change, as it is considered a carbon stock.

Declaration

We certify that the doctoral student and her advisor had permission and license to collect seeds of Virola surinamensis at the Institute of Agricultural Sciences of the Federal Rural University of the Amazon, as well as to conduct her experiment for her doctoral thesis at the Institute, comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Data availability

The data generated in this research is in the hands of the person responsible for the research, Dayse Gonzaga Braga, who is available to provide any data that the evaluation process suggests, without any objection, the relevant data has not yet been placed on any platform.

References

Andrade, M. G. et al. Heavy metals in soils from lead mining and metallurgy areas: I-Phytoextraction. Braz. J. Soil Sci. 33(6), 1879–1888 (2009).

Ren, T. et al. Biochar for cadmium pollution mitigation and stress resistance in tobacco growth. Environ. Res. 192, 110273 (2021).

Ali, H., Khan, E. & Sajad, M. A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals-concepts and applications. Chemosphere 91, 869–881 (2013).

DalCorso, G., Fasani, E., Manara, A., Visioli, G. & Furini, A. Heavy metal pollutions: State of the art and innovation in phytoremediation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 3412 (2019).

Jacob, J. M. et al. Biological approaches to tackle heavy metal pollution: A survey of literature. J. Environ. Manage. 217, 56–70 (2018).

Peng, J. S., Ding, G., Meng, S., Yi, H. Y. & Gong, J. M. Enhanced metal tolerance correlates with heterotypic variation in SpMTL, a metallothionein-like protein from the hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 1368–1378 (2017).

Peng, J. S. et al. A pivotal role of cell wall in cadmium accumulation in the crassulaceae hyperaccumulator sedum plumbizincicola. Mol. Plant. 10, 771–774 (2017).

Luo, J.-S. & Zhang, Z. Mechanisms of cadmium phytoremediation and detoxification in plants. Crop J. 9(3), 521–552 (2021).

Khan, M. A., Khan, S., Khan, A. & Alam, M. Soil contamination with cadmium, consequences and remediation using organic amendments. Sci. Total Environ. 601–602(1), 1591–1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.030 (2017).

Andrade Júnior, W. V. et al. Effect of cadmium on young plants of Virola surinamensis. AoB Plants https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plz022 (2019).

Hédiji, H. et al. Impact of prolonged exposure to cadmium on the mineral content of Solanum lycopersicum plants: Consequences on fruit production. S. Afr. J. Bot. 97, 176–181 (2015).

Järup, L. & Åkesson, A. Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 238, 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2009.04.020 (2009).

Ogawa, T. et al. Relationship between the prevalence of patients with Itai-itai disease, prevalence of abnormal urinary findings, and cadmium concentrations in rice from individual villages in the Jinzu River basin, Toyama Prefecture of Japan. Inter. J. Environ. Health Res. 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603120410001725586 (2004).

Huang, B. et al. Root morphological responses of three pepper cultivars to Cd exposure and their correlations with Cd accumulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 22, 2 (2015).

Jinadasa, N., Collins, D., Holford, P., Milham, P. J. & Conroy, J. P. Reactions to cadmium stress in a cadmium-tolerant cabbage variety Brassica oleracea L.): is cadmium tolerance necessarily desirable in food crops?. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 23(6), 5296–5306 (2016).

Lösch, R. Plant mitochondrial respiration under the influence of heavy metals. Heavy metal stress in plants: From biomolecules to ecosystems (Prasad Mnv, 2004).

Li, X., Zhou, Q., Sun, X. & Ren, W. Effects of cadmium on uptake and translocation of nutrient elements in different welsh onion Allium fistulosum L.) cultivars. Food Chem. 194, 101–110 (2016).

Mysliwa-Kurdziel, B., Prasad, M. N. V., Strzaltka, K. Photosynthesis in Heavy Metal Stressed Plants. Berlim, Heidelberg: Prasad MNV. (2019)

Nogueirol, R. C., Monteiro, F. A., Gratão, P. L., da Silva, B. K. A. & Azevedo, R. A. Application of cadmium in tomatoes: Nutritional imbalance and oxidative stress. Pollut water air soil. 227, 6 (2016).

Shaw, B. P., Sahu, S. K. & Mishra, R. K. Heavy metal-induced oxidative damage in land plants (Springer, 2004).

Brtnicky, M. et al. A critical review of the possible adverse effects of biochar in the soil environment. Sci. Total Environ. 796, 148756 (2021).

Joseph, S. et al. How biochar works, and when it doesn’t: A review of mechanisms controlling soil and plant responses to biochar. GCB Bioenergy. 13, 1731–1764 (2021).

Naz, R. et al. Assessment of phytoremediation potential of native plant species naturally growing in a heavy metal-polluted industrial soils. Braz. J. Biol. 84, e264473 (2022).

Shen, M. et al. Recent advances in toxicological research of nanoplastics in the environment: A review. Environ. Pollut. 252, 511–521 (2019).

Cui, L. et al. Continuous immobilization of cadmium and lead in biochar amended contaminated paddy soil: A five-year field experiment. Ecol. Eng. 93, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.05.007 (2016).

Meng, J. et al. Changes in heavy metal bioavailability and speciation from a Pb-Zn mining soil amended with biochars from co-pyrolysis of rice straw and swine manure. Sci. Total Environ. 633, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.199 (2018).

de Veloso, V. L. et al. Phytoattenuation of Cd, Pb, and Zn in a Slag-contaminated Soil Amended with Rice Straw Biochar and Grown with Energy Maize. Environ. Manage. 69, 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01530-6 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Analysis of the long-term effectiveness of biochar immobilization remediation on heavy metal contaminated soil and the potential environmental factors weakening the remediation effect: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111261 (2021).

Ambaye, T. G. et al. Mecanismos e capacidades de adsorção de biochar para a remoção de poluentes orgânicos e inorgânicos de águas residuais industriais. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 3273–3294 (2021).

Hu, G., Huang, S., Chen, H. & Wang, F. Ligação de quatro metais pesados a hemiceluloses de farelo de arroz. Food Res. Int. 43, 203–206 (2010).

Munir, M. A. M. et al. Synergistic effects of biochar and processed fly ash on bioavailability, transformation and accumulation of heavy metals by maize (Zea mays L.) in coal-mining contaminated soil. Chemosphere 240, 124845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124845 (2020).

Nejad, Z. D. et al. Effects of fine fractions of soil organic, semi-organic, and inorganic amendments on the mitigation of heavy metal(loid)s leaching and bioavailability in a post-mining area. Chemosphere https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129538 (2021).

Yuan, C. et al. A meta-analysis of heavy metal bioavailability response to biochar aging: Importance of soil and biochar properties. Sci. Total Environ. 756, 144058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144058 (2021).

Sato, M. K. et al. Biochar from Acai agroindustry waste: Study of pyrolysis conditions. Waste Manage. 96, 158–167 (2019).

Sato, M. K. et al. Biochar as a sustainable alternative to açaí waste disposal in Amazon. Brazil. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 139, 36–46 (2020).

Boro, R. M., Baruah, N. & Gogoi, N. Impact of biochar and lime on phytoavailability of Pb and Cd in a contaminated soil. Trop. Agric. Res. 32, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.4038/tar.v32i2.8460 (2021).

Brasil, E. C. et al. Liming and fertilization recommendations for the state of Pará: Soil analysis methods and representation of results. Brasília: Embrapa. (2020)

Brasil, E. C., Cravo, M. S., Veloso, C. A. C. Amostragem do solo – Parte 1: Aspectos gerais relacionados ao uso de fertilizantes e corretivos. Pará: EMBRAPA. (2020)

Donagemma, G. K. et al. Manual of Soil Analysis Methods: Granulometric Analysis. Brasília: Embrapa. (2017)

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Annual book of ASTM standards D1762–84 281–282. USA: Philadelphia. (2001).

Kul, R. et al. Biochar as an organic soil conditioner for mitigating salinity stress in tomato. Soil Sci. and Plant Nutrit. 67(6), 693–706 (2021).

Zahra, M. B. et al. Mitigation of Degraded Soils by Using Biochar and Compost: a Systematic Review. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. 21, 2718–2738, (2021).

Barbosa, J. C., Maldonado Junior, W. AgroEstat - Sistema para Análises Estatísticas de Ensaios Agronômicos. Jaboticabal. (2014)

Ge, W. et al. Cadmiummediated oxidative stress and ultrastructural changes in root cells of poplar cultivars. S. Afr. J. Bot. 83, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2012.07.026 (2012).

Pietrini, F. et al. Spatial distribution of cadmium in leaves and its impact on photosynthesis: Examples of different strategies in willow and poplar clones. Plant. Biol. 12(2), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00258.x (2010).

Zhao, H. et al. Effects of cadmium stress on growth and physiological characteristics of sassafras seedlings. Sci. Rep. 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89322-0 (2021).

Lyu, H. Biochar/iron (BC/Fe) composites for soil and groundwater remediation: Synthesis, applications, and mechanisms. Chemosphere 246, 125609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125609 (2020).

Sohi, S. P. Carbon storage with benefits. Science 338(6110), 1034–1035 (2012).

Miyadate, H. et al. Os HMA3, a P1B-type of ATPase affects root-to-shoot cádmium translocation in rice by mediating efflux into vacuoles. New Phytol. 189, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03459.x (2011).

Ferreira, N. K. F. et al. Availability of heavy metals and their correlation with soil organic matter in vegetable producing areas in the Metropolitan region of Belém/Pa. Braz. J. Dev. 7(11), 109022–109032 (2021).

Gutsch, A. et al. Changes in the proteome of leaves in response to long-term cadmium exposure using a cell-wall targeted approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2498 (2018).

Sharma, K., Dietz, J. & Mimura, T. Vacuolar compartmentalization as indispensable component of heavy metal detoxification in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 1112–1126 (2016).

Kartel, M. T., Kupchik, L. A. & Veisov, B. K. Evaluation of pectin binding of heavy metal ions in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 38, 2591–2596 (1999).

Paynel, F., Schaumann, A., Arkoun, M., Douchiche, O. & Morvan, C. Temporal regulation of cell-wall pectin methylesterase and peroxidase isoforms in cadmium-treated flax hypocotyl. Ann. Bot. 104, 1363–1372 (2009).

Rahimzadeh, S. & Ghassemi-Golezani, K. Biochar-based nutritional nanocomposites altered nutrient uptake and vacuolar H+ pump activities of dill under salinity. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 22(3), 3568–3581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-022-00910-z (2022).

Rahimzadeh, S. & Ghassemi-Golezani, K. The roles of nanoparticle-enriched biochars in improving soil enzyme activities and nutrient uptake by basil plants under arsenic toxicity. Intern. J. Phytorem. 27(3), 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2024.2416997 (2024).

Bruun, E. W., Petersen, C. T., Hansen, E., Holm, J. K. & Hauggaard-Nielsen, H. Biochar amendment to coarse sandy subsoil improves root growth and increases water retention. Soil Use Manage. 30, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12102 (2014).

He, B., Gu, M., Wang, X. & He, X. The effects of lead on photosynthetic performance of waxberry seedlings (Myrica rubra). Photosynthetica 56(4), 1147–1153 (2018).

Martins, L. D. et al. Manejo nutricional e suplementação hídrica. Alegre: CAUFES. (2018)

Conceição, S. S. Phytoremediation of cadmium by Khaya ivorensis A. chev. mitigation of silicon stress in physiological, biochemical and anatomical modulations. [thesis/doctoral thesis]. [(Belém (PA)]: Federal Rural University of the Amazon. (2020)

Sun, H. J., Zhang, H. C., Shi, W. M., Zhou, M. Y. & Ma, X. F. Effect of biochar on nitrogen use efficiency, grain yield and amino acid content of wheat cultivated on saline soil. Plant Soil Environ. 65, 83–89 (2019).

Akhtar, S. S., Andersen, M. N., Naveed, M., Zahir, Z. A. & Liu, F. Interactive effect of biochar and plant growth promoting bacterial endophytes on ameliorating salinity stress in maize. Funct. Plant Biol. 42, 770–781 (2015).

Gashi, B., Buqaj, L., Vataj, R. & Metin Tuna, M. Chlorophyll biosynthesis suppression, oxidative level and cell cycle arrest caused by Ni, Cr and Pb stress in maize exposed to treated soil from the Ferronikel smelter in Drenas. Kosovo. Plant Stres. 11, 100379 (2024).

Hanaka, A., Jaroszu-Ściseł, J., Majewska, M. (Eds.). Study of the Influence of Abiotic and Biotic Stress Factors on Horticultural Plants; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland. (2022)

Hanaka, A., Majewska, M., Hawrylak-Nowak, B. (Eds.). Horticultural Plants Facing Stressful Conditions—Ways of Stress Mitigation; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland. (2023)

Kharrazi, S. M. et al. A novel post-modification of powdered activated carbon prepared from lignocellulosic waste through thermal tension treatment to enhance the porosity and heavy metals adsorption. Powder Technol. 366, 1 (2020).

Taiz, L., Zeiger, E., Moller, I. M., Murphy, A. Fisiologia e desenvolvimento vegetal. Porto Alegre: Artmed. (2017)

Goncharuk, E. A. & Zagoskina, N. V. Heavy Metals, Their Phytotoxicity, and the Role of Phenolic Antioxidants in Plant Stress Responses with Focus on Cadmium: Review. Molecules 28(9), 3921. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28093921 (2023).

Osman, A. I. et al. Biochar for agronomy, animal farming, anaerobic digestion, composting, water treatment, soil remediation, construction, energy storage, and carbon sequestration: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 4 (2022).

Osman, A. I. et al. Recent advances in carbon capture storage and utilisation technologies: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 2 (2020).

Huang, X. F. et al. The effects of biochar and dredged sediments on soil structure and fertility promote the growth, photosynthetic and rhizosphere microbial diversity of Phragmites communis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. Sci. Total Environ. 697, 134073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134073 (2019).

Liu, Q. et al. How does biochar influence soil N cycle?. A meta-analysis. Plant Soil. 426, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3619-4 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. Adaptive response of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis to accumulation of elements and translocation in Phragmites australis affected by cadmium stress. J. Environ. Manag. 197, 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.014 (2017).

Asai, H. et al. Biochar amendment techniques for upland rice production in Northern Laos 1. Soil physical properties, leaf SPAD and grain yield. Field Crops Res. 111, 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2008.10.008 (2009).

Alkherraz, A. M., Ali, A. K. & Elsherif, K. M. Removal of Pb (II), Zn (II), Cu (II) and Cd (II) from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto olive branches activated carbon: Equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Int. 6, 1 (2020).

Küpper, H., Parameswaran, A., Leitenmaier, B., Trtilek, M. & Šetlík, I. Cadmium-induced inhibition of photosynthesis and long-term acclimation to cadmium stress in the hyperaccumulator Thlaspicaerulescens. New Phytol. 175, 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02139.x (2007).

Ying, R. R. et al. Cadmium tolerance of carbon assimilation enzymes and chloroplast in Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator Picris divaricata. J. Plant Physiol. 167(2), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2009.07.005 (2010).

Zhang, F., Liu, M., Li, Y., Che, Y. & Xiao, Y. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, biochar and cadmium on the yield and elemento uptake of Medicago sativa. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.317 (2019).

Nogueira, G. A. S. et al. Physiological and growth responses in the (Schizolobium amazonicum Huber ex Ducke) seedlings subjected to cadmium doses. J. Agricult. Sci. 11(8), 217 (2019).

Hasanuzzaman, M., Nahar, K., Alam, M. M., Fujita, M. Adverse Effects of Cadmium on Plants and Possible Mitigation of Cadmium-Induced Phytotoxicity. Nova Iorque: Mirza Hasanuzzaman & Masayuki Fujita. (2013)

Ivanov, A. A. & Kosobryukhov, A. A. Ecophysiology of plants under cadmium toxicity: Photosynthetic and physiological responses. In Plant Ecophysiology and Adaptation under Climate Change: Mechanisms and Perspectives I (ed. Hasanuzzaman, M.) 429–484 (Springer: Singapore, 2020).

Naeem, A. et al. Cadmium-Induced Imbalance in Nutrient and Water Uptake by Plants. In Cadmium Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants 299–326 (Elsevier, 2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Effects of environment lighting on the growth, photosynthesis, and quality of hydroponic lettuce in a plant factory. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 11, 33–40 (2018).

Fu, W. G. & Wang, F. K. Effects of high soil lead concentration on photosynthetic gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence in Brassica chinensis L. Plant, Soil Environ. 61(7), 316–321 (2015).

Marques, D. M., Silva, A. B., Mantovani, J. R., Pereira, D. S. & Souza, T. C. Growth and physiological responses of tree species (Hymenaea courbaril L., Peltophorum dubium (Spreng.) Taub. and Myroxylon peruiferum L. F.) exposed to different copper concentrations in the soil. J. Tree. 42(2), 1–11 (2018).

Volpe, J. Characterization and feasibility study in the application of adsorbents as samplers used to collect naphthalene and formaldehyde. (monograph/graduation monograph). [Curitiba (PR)]: Federal Technological University of Paraná. (2017)

Ferreira, R. L. C. et al. Biochar improves growth and physiology of Swietenia macrophylla king in contaminated soil by copper. Sci. Rep. 14, 22546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74356-x (2024).

Abdullah, B. et al. Fourth generation biofuel: A review on risks and mitigation strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 107, 37–50 (2019).

Abdullah, N. et al. Preparation of nanocomposite activated carbon nanofiber/manganese oxide and its adsorptive performance toward leads (II) from aqueous solution. J. Water Process Eng. 37, 1 (2020).

Zhao, G., Xu, H., Zhang, P., Su, X. & Zhao, H. Effects of 2 4 epibrassinolide on photosynthesis and Rubisco activase gene expression in Triticum aestivum L. seedlings under a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Growth Regul. 81, 377 (2017).

Farooq, M., Ullah, A., Usman, M. & Siddique, K. H. M. Application of zinc and biochar help to mitigate cadmium stress in bread wheat raised from seeds with high intrinsic zinc. Chemosphere 260, 127652 (2020).

Shaaban, M. et al. A concise review of biochar application to agricultural soils to improve soil conditions and fight pollution. J. Environ. Manag. 228, 429–440 (2018).

Ahmad, I., Akhtar, M. J., Zahir, Z. A. & Mitter, B. Organic amendments: Effects on cereals growth and cadmium remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 12, 2919–2928 (2015).

Dharma-Wardana, M. W. C. Fertilizer usage and cadmium in soils, crops and food. Environ. Geochem. Health 40, 2739–2759 (2018).

Forster, S. M., Rickertsen, J. R., Mehring, G. H. & Ransom, J. K. Type and placement of zinc fertilizer impacts cadmium content of harvested durum wheat grain. J. Plant. Nutr. 41, 1471–1481 (2018).

Feki, K., Tounsi, S., Mrabet, M., Mhadhbi, H. & Brini, F. Recent advances in physiological and molecular mechanisms of heavy metal accumulation in plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 64967–64986 (2021).

Ghori, N. H. et al. Heavy metal stress and responses in plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 1807–1828 (2019).

Yaashikaa, P. R., Kumar, P. S., Jeevanantham, S. & Saravanan, R. A review on bioremediation approach for heavy metal detoxification and accumulation in plants. Environ. Pollut. 301, 119035 (2022).

Sidhu, G. P. S., Bali, A. S. & Bhardwaj, R. Role of organic acids in mitigating cadmium toxicity in plants. In Cadmium tolerance in plants 255–279 (Academic Press, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815794-7.00010-2.

Acknowledgements

The Amazon Foundation for Support of Studies and Research (FAPESPA), Federal Rural University of the Amazon (UFRA) and the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Amapá (IFAP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DGB: responsible for administering the experiment and writing the text. RLCF: responsible for contextualizing and writing the text. CBS and JACC: conducted the experiment. ACBA: performed the statistical analysis, tables and figures. AEAB: responsible for supervising and validating the data. VRN: responsible for translating the text. LCS: responsible for editing the text. CFON: responsible for the analyses performed. All reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Braga, D.G., Ferreira, R.d., da Silva, C.B. et al. Biometric and physiological responses of Virola Surinamensis to cadmium and biochar in amazonian soil. Sci Rep 15, 21325 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05656-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05656-z