Abstract

The low-temperature oxidation of hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) during oxidative dehydrogenation of propane (ODHP) is investigated using a combination of experimental techniques and theoretical modeling. This study explores the role of gas-phase radicals, such as n-propyl and hydroxyl radicals, in initiating the oxidation process, leading to the formation of oxygen-functionalized h-BN edges. Using ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, we reveal the mechanism of h-BN oxidation, including hydrogen abstraction, molecular oxygen adsorption, and nitrogen oxide desorption. Experimental results confirm that oxidation occurs only in the presence of both oxygen and propane, demonstrating a critical dependence on reactor geometry on gas-phase radical generation. The oxidation process leads to the incorporation of oxygen into h-BN, forming boron oxyhydroxide phases that influence catalytic activity. These findings provide new insights into h-BN behavior under ODHP conditions and offer guidance for optimizing boron-based catalysts for selective alkane dehydrogenation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The catalytic oxidative dehydrogenation of alkanes offers a promising alternative to energy-intensive cracking or traditional dehydrogenation processes for producing propene and other olefins1,2. Using suitable catalysts, such as supported VOx materials3, propene can be produced via oxidative dehydrogenation of propane (ODHP) with high conversions, lower reaction temperatures, and catalyst stability with minimal coke formation. However, its industrial application is challenged by low propene selectivity at high propane conversions due to over-oxidation, resulting in reduced yields. Recently, Grant et al. reported that hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) exhibits unexpectedly high catalytic activity in the ODHP process, characterized by very high olefin selectivity (79% propene and 12% ethene) at 490 °C with a propane conversion of 14%4. Compared to VOx-based catalysts, a significantly lower production of CO and CO2 was observed5.

The discovery of h-BN’s catalytic activity in ODHP drove significant efforts within the catalytic research community to elucidate the reaction mechanism of ODHP over boron-based catalysts6. Despite significant progress, the underlying mechanism remains elusive. In particular, there is ongoing discussion regarding the contribution of gas-phase reactions and the nature of active sites on h-BN in the context of the ODHP process7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

There is currently a general consensus in the literature that the catalytic activity of boron-based materials, including h-BN, is linked to the formation/presence of the amorphous boron oxyhydroxide phase (denoted as BOx from now on)9,24,25,26,27. At 490 °C, this phase is in a liquid state and, in its pure form, does not significantly enhance the ODHP catalytic activity28. As the temperature increases, the catalytic activity starts to rise. The lack of catalytic activity in unsupported BOx liquid at 490 °C might suggest that active sites are not solely associated with the liquid phase but also arise from specific interactions at the BOx-support interface. These interactions could alter the electronic and structural properties of the catalytic phase, facilitating the formation of active species capable of participating in the ODHP reaction. Additionally, the gradual rise in catalytic activity with temperature indicates that structural rearrangements or compositional changes within the BOx phase at the BOx-support interface might be essential for optimizing catalytic performance29.

The reaction kinetics studies suggest that the catalytically enhanced ODHP reaction proceeds via a radical mechanism similar to propane`s low-temperature (318 °C) oxidation7,11,30. The product distribution in the gas-phase reaction closely resembles that observed on boron-containing catalysts. Moreover, a comprehensive theoretical analysis indicates that the gas-phase chemistry dominates ODHP on boron nitride11. For h-BN at 490 °C, the formation of the BOx phase involves an induction period during which propane conversion gradually increases9. This increase in activity has been correlated with the observed increasing oxygen concentration in h-BN25,31. This oxy-functionalization of h-BN leads to the formation of various B-O functional groups, as well as small BOx nanoparticles. Note that h-BN, a widely used ceramic known for its excellent chemical resistance and high thermal stability, remains inert in dry oxygen up to 900 °C32,33. Even monolayer h-BN remains stable in oxygen until the temperature surpasses 840 °C34. At 490 °C, it also exhibits inert behavior in a propane atmosphere. Thus, the ODHP gas phase reaction is likely responsible for the observed induction period during which h-BN is activated. The mechanism of oxygen incorporation into h-BN and the formation of oxy-functionalities has not yet been investigated in detail and satisfactorily explained. These findings spark interest in the low-temperature (below 500 °C) h-BN oxidation process, particularly regarding the oxy-functionalization of h-BN edges and the formation of the BOx phase under the ODHP reaction conditions.

Given the ongoing debate surrounding the nature of active sites and the role of gas-phase reactions in ODHP over h-BN, a detailed theoretical investigation is necessary to elucidate the underlying oxidation mechanism. In this study, we employ ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations to explore the interactions between h-BN and reactive molecular species under ODHP conditions. Representative models of h-BN are utilized to analyze transition states associated with edge oxidation. By integrating experimental observations with computational insights, we aim to establish a mechanistic framework describing the low-temperature oxidation of h-BN and its impact on ODHP activity. In particular, we investigate the role of radical species in initiating oxidation, the formation of oxygenated edge structures, and their subsequent transformation into active catalytic sites. The findings from this study provide a deeper understanding of h-BN’s behavior under reaction conditions, guiding the design of more efficient boron-based catalysts for selective alkane oxidative dehydrogenation.

Methods

Experimental

This study used hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN, particle size one µm) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (product no. 255475). The material was treated at 490 °C for three h in a gas mixture consisting of C3H8/O2/He = x/y/(100-(x + y)) vol%, where x = 0 or 30 and y = 0 or 15, and total flow rate of 20 ml min–1. Treatment was carried out in tubular reactors of different diameters (internal diameter: 9, 10, 12.3, 14.5, 15.5 mm) having free unfilled volumes in the reaction zone of sizes 1.57, 2.08, 3.45, 5.02, and 5.82 ml.

The surface chemical composition of the samples after various treatments was monitored by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (ESCA2SR, Scienta-Omicron) using a monochromatic Al Kα (1486.7 eV) X-ray source. The binding energy scale was referenced to appendant carbon (284.8 eV). The chemical changes occurring in h-BN during the catalytic oxidative dehydrogenation of propane were also monitored by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFT spectroscopy). DRIFT spectroscopy was measured with a Harrick-Praying-Mantis flow-through high-temperature accessory. The variously treated powder sample was loaded into a ceramic dish in a DRIFT cell and conditioned by heating from RT to 400 °C with a heating ramp of 10 °C/min in a nitrogen stream (purity 99.999% supplied by Linde gas Corp., flow rate 15 ml. min–1) for dehydration. Then, the IR spectra of the dehydrated samples were collected by accumulating 1024 scans with an optical resolution of 2 cm–1.

Models and calculations

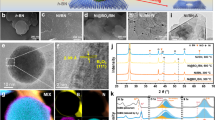

Two representative models of h-BN material were used, as shown in Fig. 1. The first model (Fig. 1a) was employed for computational convenience in qualitative AIMD simulations. The 7 × 7 × 1 supercell of h-BN, including the defect, was optimized using the PBE-D335,36 level of theory with an 800 eV plane-wave energy cut-off. The resulting lattice parameters were a = 17.55 Å, b = 17.52 Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120 Å, and the layer separation in the c-direction was set to 12.5 Å. Unsaturated bonds were terminated with OH groups for boron and hydrogen for nitrogen.

The h-BN “flake” model (Fig. 1b) was used to determine the transition state structures during interactions with various radicals and molecular oxygen, modeling the oxidation of the h-BN layer under ODH conditions37,38. The layer was enclosed in a rectangular cuboid with a = b = 25 Å and layer separation of 15 Å. All relative energies (ΔEr) and activation barriers (ΔEa) were calculated at the PBE-D3 level with a plane-wave energy cut-off of 400 eV in the VASP code39,40. The correction to the free energy (ΔGr) at 490 °C was calculated at PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory using ideal gas approximation as implemented in G16 program suite41. High-temperature oxidation (900 °C) with oxygen was studied by adding 21 molecular oxygen molecules into the simulation box (Fig. 1a). This was performed using NVT AIMD with a Nosé-Hoover thermostat for approximately 100 ps, with a time step of 1 fs. Note that the hydrogen mass was increased to that of deuterium to accommodate this larger time step42. Additionally, a shorter simulation of about 30 ps was conducted with molecular oxygen after removing the terminating hydrogens from the structure in Fig. 1a, thereby forming reactive edges. The observed mechanisms from high-temperature oxidation were used to propose a mechanism for h-BN oxidation under ODH conditions. The initial and final stationary points, including spin polarization, were optimized with SCF convergence set to 10–6 eV and gradients smaller than 10− 2 eV/Å. The transition states were located using the CI-NEB and/or dimer algorithms43,44.

Results and discussion

The ODHP over the h-BN catalyst is a complex process influenced by gas-phase and surface reactions. A cornerstone of this study is that molecular oxygen alone does not oxidize h-BN under ODHP conditions, highlighting the necessity of additional reactive species for initiating the oxidation process. We assume that radicals formed in the C3H8/O2/He gas-phase mixture, such as n-propyl and hydroxyl radicals, play a crucial role in activating the h-BN edges at lower temperatures below 500 °C.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that h-BN oxidation strongly depends on the reactor geometry, with smaller reactor volumes exhibiting lower activity due to faster radical quenching. Furthermore, reactor volume and shape optimization indicate that h-BN is not strictly required to achieve significant propane conversion (~ 30%)8. However, its presence enhances propane conversion without compromising selectivity toward olefin products, suggesting that h-BN participates in the reaction by modulating radical availability or surface reactivity.

Based on these observations, we propose that h-BN activation begins with hydrogen abstraction at the h-BN edge, facilitated by reactive radicals in the gas-phase mixture. The key step in h-BN oxidation involves the formation of > N–O species at the edges, which render the material susceptible to O₂ attack at > B–N(O)–B < sites. This process leads to O₂ chemisorption and NO desorption, as evidenced by a measurable decrease in nitrogen content in h-BN catalysts exposed to ODH conditions (Fig. 2). Subsequent oxidation steps involve the formation of > B–O–O–B < sites, which promote oxygen dissociation, leading to the generation of oxygen radicals and the formation of six-membered rings where nitrogen is replaced by oxygen. Notably, transition states with attached oxygen radicals are unstable, allowing oxygen to diffuse along the h-BN surface and progressively incorporate into the h-BN structure. This mechanism aligns with high-temperature oxidation pathways of h-BN, where oxygen radical species integrate into B–N bonds, ultimately forming unstable seven-membered rings at the material’s edges.

These findings provide new insights into the dynamic nature of h-BN under ODH conditions and its interaction with reactive oxygen species, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of its catalytic role.

Initial step in the low-temperature oxidation of h-BN: edge activation

Table 1 summarizes the H-abstraction process for common radical species present in the ODHP gas-phase mixture at 490 °C, including molecular oxygen for reference. We were unable to locate stationary points on the corresponding potential energy surfaces (i.e., the energy barriers for hydrogen abstraction from the h-BN edges) for HOO• and n-C3H7OO• radicals. In these cases, the energy difference between reactants and products is expected to drive the process. Among the most reactive species is the HO• radical (cf. Table 1), which can abstract hydrogen without any barrier, and the reaction is exothermic. However, the formation of HO• in the ODHP process typically leads to aldehydes, cyclic ethers, and alkoxy radical species, which are not observed as products in ODHP over h-BN at 490 °C.

Figure S2 shows the energetics of hydrogen abstraction from the h-BN edges by the n-C3H7• radical. The > BO• radical formed on the armchair(O) edge is about 30 kJ.mol–1 more stable than > BO• and > N• on other edges, making this process quite favorable with a barrier of 69 kJ.mol–1. Nevertheless, the barriers (69–104 kJ.mol− 1) and overall energetics indicate that n-C3H7• can abstract hydrogen from any h-BN edge under ODHP conditions.

The assumption that hydrogen atoms are stripped from the h-BN edges during the induction period via radical species present in the gas-phase ODHP reaction at 490 °C supports our exploratory AIMD simulations with activated h-BN edges (i.e., without terminating hydrogens) in the presence of molecular oxygen. These simulations were conducted to elucidate the oxidation pathways of h-BN under ODHP conditions (Figures S4-S6).

Oxidation on the armchair edge

The oxidation on the armchair edge can be summarized as follows (Scheme 1): Upon edge activation (i.e., the removal of hydrogen atoms from adjacent BOH and NH groups), a five-membered ring (5MR) is formed. The boron atom in the 5MR is highly susceptible to attack by molecular oxygen, resulting in the formation of terminal BOO and NO groups. The formation of the B-O-O terminal group is energetically more favorable than that of O-B-O by 21 kJ.mol–1.

Additional O₂ adsorption leads to NO dissociation from the h-BN edge and the formation of unstable > B-O-O-B < edge species, replacing the nitrogen atom with oxygen. The > B-O-O-B < edge structure can transform into a more stable six-membered ring with > B-O-B < and an adsorbed oxygen radical, which can diffuse across the h-BN surface and further oxidize the material via high-temperature oxidation pathways. Both steps, detachment of NO and O-O cleavage, are opposed by a barrier of about 60 kJ.mol–1 (Scheme S1).

Oxidation on the zig-zag(N) edge

The oxidation on the zig-zag(N) edge proceeds in a similar manner to the armchair edge. Adsorption of molecular oxygen on activated nitrogen atoms (second structure in Scheme 2) leads to barrier-free oxygen dissociation and the formation of two terminating NO groups. The AIMD simulations show that the presence of NO groups activates the boron atom in-between, strongly stabilizing the adsorption complex with the oxygen molecule by 44 kJ.mol–1. Adjacent boron atoms in > B-N(O)-B < are again susceptible to oxygen attack, which leads to the formation of an unstable > B-O-O-B < structure and the detachment of the NO molecule. The significant difference compared to the mechanism observed on the armchair edge lies in further oxygen reshuffling where > B-O-O-B < rearranges into > B-O-B < and oxygen radical directly embeds itself in the adjacent six-membered ring (see Scheme S3). Oxygen atom insertion into six-membered rings of h-BN was frequently observed in our high-temperature AIMD simulations.

Molecular oxygen can also be chemisorbed on a single activated N site, followed by an oxygen attack that leads to NOO desorption. Compared to the previous mechanism involving two adjacent N sites, this process is much less favorable due to a barrier of 177 kJ.mol–1. This mechanism is outlined in Scheme S2 of the Supporting Information.

Stepwise oxidation mechanism of the zig-zag(N) edge. The oxygens coming from the gas phase are denoted with blue color, and a more detailed picture, including relative energies, is provided in Scheme S3 of the Supporting Information.

Oxidation on the zig-zag(O) edge

The oxidation on the zig-zag(O) edge is the most energetically unfavorable because this edge, even upon activation (i.e., hydrogen abstraction), does not interact with molecular oxygen. Two hydrogen abstractions lead to the formation of > B-O-O-B < species, which appear to be relatively stable and unreactive throughout our AIMD simulations. Thus, an initial step is required to break at least one B-N bond on this edge to initiate the oxidation process. We propose that an oxygen radical attack near the > B-OH group, followed by molecular oxygen adsorption, triggers NO dissociation from the h-BN layer. Note that oxygen radical species are formed during the oxidation of other h-BN edges.

The most favorable pathway found in our exploratory AIMD simulations starts with oxygen radical insertion (Scheme 3). Upon forming the seven-membered ring (7MR), the planarity of the system is severely compromised (Figure S3). The formation of the 7MR appears to be sufficient to disrupt the edge integrity, leading to ring opening and the formation of the terminating NO group (last structure in Scheme 3), as well as a dangling BO• radical anchored to just a single nitrogen atom. It is straightforward that, upon an additional O₂ attack on > BNOB < and the release of NO, the BOx phase attached to h-BN is formed.

Stepwise oxidation mechanism of the zig-zag(O) edge. The oxygen radical is denoted with a blue color, and a more detailed picture, including relative energies, is provided in Scheme S4 of the Supporting Information.

Validation of simulation results with experimental observations

Theoretical simulations have shown that low-temperature oxidation of h-BN begins with edge activation by radical attack (most likely HO• or n-C3H7•) and subsequent interaction with molecular oxygen, which leads to the release of nitrogen in the form of nitrogen oxides and the formation of unstable > B-O-O-B < groups followed by the O-O bond cleavage. Oxygen radicals can attack other atoms of the h-BN framework, deepening the oxidation of h-BN. These findings are supported by experimental observations, which we present in this section.

Figure 2 shows the chemical composition (expressed in at%) of h-BN samples treated in different atmospheres at 490 °C for three hours, determined by photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The data clearly indicate that the oxygen content remains constant at approximately 5 at%—the same level as in the untreated (fresh) h-BN sample—after treatment in pure helium, a helium-oxygen mixture, or a helium-propane mixture. Similarly, the nitrogen-to-boron ratio remains unchanged across all samples, except for the one exposed to the full reaction mixture containing both oxygen and propane. This suggests that oxidation of h-BN at 490 °C does not occur in the presence of oxygen alone; instead, both oxygen and propane are required for the oxidation process to start.

After three hours of exposure to a gas mixture containing both oxygen and propane, the oxygen content in the treated sample increased significantly to 22 at%, while the nitrogen content decreased from 45 at% to 34 at%, leading to a drop in the nitrogen-to-boron ratio from 1.0 ± 0.01 in the other samples to 0.79. These results confirm that h-BN oxidation occurs only when both oxygen and hydrocarbon are present in the gas mixture. The incorporation of oxygen into h-BN occurs at the expense of nitrogen, as supported by theoretical simulations and previous studies25,31.

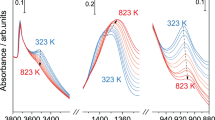

The oxy-functionalization of h-BN during ODH reaction is also highlighted in the IR spectra of h-BN samples (Fig. 3). Comparing the untreated and the reaction-treated h-BN, it is evident that after treatment in the reaction mixture, the vibrational bands belonging to isolated BOH groups (bands at 3680–3698 cm− 1)45 on the edges of h-BN disappear, while the BO-H vibrations disturbed by hydrogen bonds of vicinal OH (~ 3579 cm–1)46 or NH groups (3390–3425 cm–1)47 remain preserved. In addition, vibrational bands appear in the IR spectrum of activated h-BN at wavenumbers 1275 and 730 cm–1, which can be assigned to the formed BOx phase (small nano-islands of boron oxide or boron oxyhydroxide)48. The changes in the IR spectra are consistent with the prediction based on AIMD simulations and the increased oxygen content in the activated h-BN.

The mechanism of low-temperature oxidation and the reason why the coexistence of oxygen and hydrocarbon in the gas mixture is necessary for the oxidation to proceed has not yet been satisfactorily explained in the literature. Our theoretical simulations point to a radical mechanism and the necessity of activation (i.e. dehydrogenation) of edges by interactions of BOH or N-H terminal groups with HOO• or n-C3H7• radicals. To confirm this hypothesis, we performed the treatment of h-BN under identical conditions (i.e., at 490 °C for three hours in a gas mixture with a flow rate of 20 ml.min–1 and the composition C3H8/O2/He = 30/15/55 vol%) in reactors with different free volume in the reaction zone, in which radicals can propagate in the reaction mixture. The free volume was reduced by using a tubular reactor with a different geometry (different inner tube diameter) or by reducing the free volume by filling the space above the h-BN with silicon carbide, which fills the void space and significantly accelerates the quenching of radicals.

(A) Oxygen content and nitrogen-to-boron ratio (determined by XPS analysis) in h-BN treated at 490 °C for three hours in the ODH reaction mixture (He/C3H8/O2 = 11/6/3 ml.min–1) as a function of the size of the void volume in the reactor realized by its different internal diameters. (B) Variation of oxygen content (determined by XPS analysis) in treated h-BN samples at 490 °C for three hours in the ODH reaction mixture (He/C3H8/O2 = 11/6/3 ml.min–1) in reactors with ID = 12.3 and 15.5 mm with filled or free space above the catalyst bed.

The rate of h-BN oxidation at 490 °C for three hours is strongly dependent on the size of the free space above the catalyst bed, in which radicals can be generated by thermal activation of gas molecules (Fig. 4). With a fourfold increase in the free volume, from 1.5 to almost 6 ml, the oxygen content in h-BN increases threefold, even though the treatment takes place under identical conditions. Partial filling of the space above the catalyst bed with a catalytically inert solid material (SiC), which acts as a radical quencher, leads to significant suppression of h-BN oxidation, regardless of the reactor geometry (Fig. 4B). The presence of SiC led to the reduction of the oxygen content in treated h-BN by about 30–35 rel. %. This is again in accordance with theoretical simulations and clearly demonstrates the essential necessity of radical generation in the gas mixture for successful h-BN oxidation.

Conclusions

This study provides new insights into the low-temperature oxidation of hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) under oxidative dehydrogenation of propane (ODHP) conditions. Our findings confirm that radical species formed in the gas-phase mixture (C3H8/O2/He), such as n-propyl and hydroxyl radicals, are critical in initiating the oxidation process by activating the h-BN surface at temperatures below 500 °C.

The experimental results demonstrate that h-BN oxidation strongly depends on reactor geometry, as smaller reactor volumes result in lower ODHP activity due to faster radical quenching. Reactor optimization studies reveal that h-BN is not essential for achieving significant propane conversion (~ 20%), yet its presence enhances conversion while preserving high selectivity toward alkene products. These findings suggest that h-BN influences the reaction through radical-mediated mechanisms rather than direct catalytic activity.

We propose that the oxidation of h-BN begins with hydrogen abstraction at the h-BN edges, primarily facilitated by reactive gas-phase radicals. The key step in this activation involves the formation of > N–O species at the edges, which render the material susceptible to O₂ attack at > B–N(O)–B < sites, leading to O₂ chemisorption and NO desorption. The subsequent formation of unstable > B–O–O–B < sites promote oxygen dissociation, generating oxygen radicals and leading to the incorporation of oxygen into the h-BN structure. These oxidation pathways align with known high-temperature oxidation mechanisms of h-BN, in which oxygen radical species integrate into B–N bonds, forming unstable seven-membered rings at the material’s edge.

Overall, our study highlights the complex interplay between gas-phase radicals and h-BN oxidation in the ODHP process. These findings not only advance the fundamental understanding of h-BN oxidation but also have implications for optimizing boron-based catalysts for selective alkane dehydrogenation. Future work should focus on further elucidating the role of gas-phase radical interactions and exploring strategies to control the oxyfunctionalization of h-BN to enhance catalytic performance.

Data availability

The XPS, FT-IR data along with structures involved in h-BN activation were placed in Zenodo data repository (DOI:10.5281/zenodo.15180743). Additional data used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zuo, C. & Su, Q. Research progress on propylene Preparation by propane dehydrogenation. Molecules 28, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28083594 (2023).

Nawaz, Z. Light alkane dehydrogenation to light olefin technologies: a comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 31, 412. https://doi.org/10.1515/revce-2015-0012 (2015).

Carrero, C. A., Schloegl, R., Wachs, I. E. & Schomaecker, R. Critical literature review of the kinetics for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over Well-Defined supported vanadium oxide catalysts. ACS Catal. 4, 3357–3380. https://doi.org/10.1021/cs5003417 (2014).

Grant, J. T. et al. Selective oxidative dehydrogenation of propane to Propene using Boron nitride catalysts. Science 354, 1570–1573. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf7885 (2016).

Grant, J. T. et al. Boron and Boron-Containing catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Chemcatchem 9, 3623–3626. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201701140 (2017).

McDermott, W. P., Cendejas, M. C. & Hermans, I. Recent advances in the Understanding of Boron-Containing catalysts for the selective oxidation of alkanes to olefins. Top. Catal. 63, 1700–1707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-020-01383-z (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Unraveling radical and oxygenate routes in the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over Boron nitride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c12970 (2023).

Nadjafi, M. et al. On the importance of benchmarking the Gas-Phase pyrolysis reaction in the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. ChemCatChem 15, 412. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.202200694 (2023).

Cendejas, M. C. et al. Tracking active phase behavior on Boron nitride during the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane using Operando X-ray Raman spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25686–25694. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c08679 (2023).

Tian, J. et al. Understanding the origin of selective oxidative dehydrogenation of propane on boron-based catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 623, 563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2021.118271 (2021).

Kraus, P. & Lindstedt, R. P. It’s a gas: oxidative dehydrogenation of propane over Boron nitride catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 5623–5634. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c00165 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Radical chemistry and reaction mechanisms of propane oxidative dehydrogenation over hexagonal Boron nitride catalysts. Angewandte Chemie - Int. Ed. 59, 8042–8046. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202002440 (2020).

Venegas, J. M. et al. Why Boron nitride is such a selective catalyst for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Angewandte Chemie - Int. Ed. 59, 16527–16535. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202003695 (2020).

Venegas, J. M., McDermott, W. P. & Hermans, I. Serendipity in catalysis research: boron-Based materials for alkane oxidative dehydrogenation. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2556–2564. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00330 (2018).

Venegas, J. M. & Hermans, I. The influence of reactor parameters on the Boron Nitride-Catalyzed oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Org. Process Res. Dev. 22, 1644–1652. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00301 (2018).

Tian, J. et al. Hexagonal Boron nitride catalyst in a fixed-bed reactor for exothermic propane oxidation dehydrogenation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 186, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2018.04.029 (2018).

Xu, H. T. A. B. Kinetic insights into boron-based materials catalyzed oxidative dehydrogenation of light alkanes (2024).

Miao, B. et al. Adsorption and activation of small molecules on Boron nitride catalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 10494–10505. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4cp00103f (2024).

Gao, X. et al. Performance descriptor of subsurface Metal-Promoted Boron catalysts for Low-Temperature propane oxidative dehydrogenation to propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c11506 (2024).

Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, D. & Lu, A. H. Suppressing deep oxidation by detached Nano-sized Boron oxide in oxidative dehydrogenation of propane revealed by the density functional theory study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 21263–21271. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c06910 (2022).

Wang, G., Yan, Y., Zhang, X., Gao, X. & Xie, Z. Three-Dimensional porous hexagonal Boron nitride fibers as Metal-Free catalysts with enhanced catalytic activity for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60, 17949–17958. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.1c04011 (2021).

Liu, Z., Lu, W. D., Wang, D. & Lu, A. H. Interplay of On- and Off-Surface processes in the B2O3-Catalyzed oxidative dehydrogenation of propane: A DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 24930–24944. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c07690 (2021).

Tian, J. et al. Dynamically formed active sites on liquid Boron oxide for selective oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. ACS Catal. 13, 8219–8236. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c01759 (2023).

Love, A. M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Silica-Supported Boron oxide catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 27000–27011. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b07429 (2019).

Love, A. M. et al. Probing the transformation of Boron nitride catalysts under oxidative dehydrogenation conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b08165 (2019).

Dorn, R. W. et al. Identifying the molecular edge termination of exfoliated hexagonal Boron nitride nanosheets with Solid-State NMR spectroscopy and Plane-Wave DFT calculations. Chem. Mater. 32, 3109–3121. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c00104 (2020).

Dorn, R. W. et al. Structure determination of Boron-Based oxidative dehydrogenation heterogeneous catalysts with ultrahigh field 35.2 T 11B Solid-State NMR spectroscopy. ACS Catal. 10, 13852–13866. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.0c03762 (2020).

Supporting Information, Figure S1 (this work).

Kurumbail, U., McDermott, W. P., Lebrón-Rodríguez, E. A. & Hermans, I. From microkinetic model to process: understanding the role of the Boron nitride surface and gas phase chemistry in the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Reaction Chem. Eng. 9, 795–802. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3re00600j (2024).

Knox, J. H. The gaseous products from the oxidation of propane at 318-Degrees-C. Trans. Faraday Soc. 56, 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9605601225 (1960).

Zhou, Y. L. et al. Enhanced performance of Boron nitride catalysts with induction period for the oxidative dehydrogenation of Ethane to ethylene. J. Catal. 365, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2018.05.023 (2018).

Jacobson, N., Farmer, S., Moore, A. & Sayir, H. High-Temperature oxidation of Boron nitride: I, monolithic Boron nitride. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 82, 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.1999.tb20075.x (1999).

Oda, K. & Yoshio, T. Oxidation-Kinetics of hexagonal Boron-Nitride powder. J. Mater. Sci. 28, 6562–6566 (1993).

Li, L. H., Cervenka, J., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Chen, Y. Strong oxidation resistance of atomically thin Boron nitride nanosheets. Acs Nano. 8, 1457–1462. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn500059s (2014).

Perdew, J., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate Ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 19. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3382344 (2010).

Rubes, M., He, J. J., Nachtigall, P. & Bludsky, O. Palladium clusters on graphene support: an Ab initio study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 646, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2015.12.065 (2016).

Rubes, M., He, J., Nachtigall, P. & Bludsky, O. Direct hydrodeoxygenation of phenol over carbon-supported Ru catalysts: a computational study. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 423, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2016.07.007 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B. 48, 13115–13115. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.48.13115 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 1758–1775. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758 (1999).

Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01Wallingford, CT (2016).

Rubeš, M. et al. Temperature dependence of carbon monoxide adsorption on a High-Silica H-FER zeolite. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 26088–26095. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b08935 (2018).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. A dimer method for finding saddle points on high dimensional potential surfaces using only first derivatives. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 7010–7022. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.480097 (1999).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Gong, Y. & Zhou, M. Matrix isolation infrared spectroscopic and theoretical study of the hydrolysis of Boron dioxide in solid argon. J. Phys. Chem. A. 112, 5670–5675. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp8014172 (2008).

Song, Y., Kim, S., Lim, M., Cho, H. B. & Choa, Y. H. Synthesis of size-controlled and in-situ OH functionalized hexagonal Boron nitride powder by hetero-phase reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 558, 563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149885 (2021).

Gültekin, K., Uğuz, G. & Özel, A. Improvements of the structural, thermal, and mechanical properties of structural adhesive with functionalized Boron nitride nanoparticles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 138, 50491. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.50491 (2021).

Netzsch, P., Pielnhofer, F., Hoppe, H. A., From S-O-S to B-O-S to B-O-B & Bridges Ba[B(S(2)O(7))(2)](2) as a model system for the structural diversity in borosulfate chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 59, 15180–15188. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02156 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Czech Science Foundation under project No. 22–23120 S. Computational resources were provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through the e-INFRA CZ (ID:90254). The authors also thank to Dr. Jhonatan Rodriguez-Pereira for help with XPS measurements and financial support of XPS infrastructure provided by Ministry of Education, Youth & Sports of the Czech Republic under project No. LM2023037.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. – Performed experimental measurements and contributed to data analysis.K.K. – Conducted experimental measurements and assisted with data analysis.R.B. – Designed the experimental setup, performed data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the experimental section of the manuscript.O.B. – Drafted most of the manuscript and contributed to data interpretation.M.R. – Wrote part of the manuscript and was responsible for theoretical calculations and their analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sajad, M., Knotková, K., Bulánek, R. et al. Low-temperature oxidation of hexagonal boron nitride during oxidative dehydrogenation reactions. Sci Rep 15, 22879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05681-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05681-y