Abstract

Zwitterionic surfactants offer unique physicochemical properties for enhanced oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs; however, their adsorption mechanisms on carbonate reservoir rocks remain incompletely understood. This study presents a comprehensive experimental and theoretical investigation into the adsorption behavior of the zwitterionic surfactant 3-(N, N-Dimethylmyristylammonio) propane sulfonate (ZW4) on calcite surfaces. The effects of key variables including salinity, temperature, pH, and surfactant concentration were systematically examined. Critical micelle concentration was measured under varying salinity and temperature conditions, and a detailed thermodynamic analysis revealed that ZW4 micellization is a spontaneous, entropy-driven process, with enthalpy-entropy compensation ensuring thermodynamic favorability across a wide temperature range. Temperature influenced the CMC non-linearly: it decreased from 10 °C to 30 °C due to reduced hydrophilicity but increased above 30 °C as hydrophobic interactions disrupted micelle formation. The roles of different electrolytes (MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄) were compared, showing that Mg²⁺ ions significantly reduced the CMC more effectively than Na⁺ ions due to stronger electrostatic double-layer compression and higher ion charge density. At 0.01 M MgSO₄, the CMC decreased from 2000 ppm to 1300 ppm, while Na₂SO₄ at the same concentration reduced it to 1700 ppm. Surface charge modifications of calcite by ZW4 were quantified using zeta potential measurements, which identified a point of zero charge near pH 6.7 and demonstrated increased surface negativity with rising surfactant concentration up to 2500 ppm. This observation is consistent with the pseudo-phase separation model. Higher pH levels inhibited adsorption due to electrostatic repulsion between ZW4’s sulfonate group and the negatively charged calcite surface. Increasing salinity enhanced adsorption, transitioning from a “V-shaped” orientation (low packing density) to a more vertical “I-shaped” configuration (high packing density), with MgSO₄ demonstrating a greater effect than Na₂SO₄, attributed to its stronger ability to neutralize surface charge. Adsorption equilibrium data, evaluated using multiple models, identified the Sips model as providing the best fit, highlighting its flexibility in describing complex adsorption phenomena. These findings provide molecular-level insight into zwitterionic surfactant–calcite interactions and underline the importance of thermodynamics, solution chemistry, and mineral surface charge for optimizing EOR surfactant flooding strategies in carbonate reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global economy depends on a stable energy supply, with oil and gas as key contributors. As easily accessible oil reserves decline, the petroleum industry focuses more on Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) methods to optimize production from existing reservoirs. Among these, surfactant flooding has gained considerable attention for its effectiveness in improving oil displacement efficiency at the pore scale1,2. Surfactants are essential in EOR due to their ability to modify interfacial properties and mobilize trapped oil in reservoirs. By reducing oil-water interfacial tension and altering rock wettability, surfactants enhance oil displacement efficiency at the microscale3,4,5. Surfactant flooding, a well-established EOR method, overcomes challenges associated with residual oil by lowering capillary forces and facilitating oil release from pore spaces6. Various surfactants, including cationic, anionic, nonionic, zwitterionic, polymeric, and naturally derived types, have been studied for their effectiveness under diverse reservoir conditions, making surfactant flooding a versatile and promising EOR strategy7,8,9. The selection of an appropriate surfactant for EOR operations is critically dependent on the reservoir’s mineralogical characteristics and the properties of its fluids10. For instance, cationic surfactants demonstrate strong performance in carbonate reservoirs due to their favorable interaction with positively charged rock surfaces11. Conversely, anionic surfactants, owing to their negative charge, exhibit enhanced efficacy in sandstone reservoirs where their electrostatic interactions with rock surfaces are more favorable12. Despite the promising potential of surfactants, their application under typical reservoir conditions poses significant challenges. High temperatures and salinity levels, common in many reservoirs, can lead to surfactant precipitation or chemical degradation13. For example, anionic surfactants may degrade via Hofmann elimination reactions, while nonionic surfactants can precipitate due to weakened hydrogen bonds. These effects are exacerbated at salinities exceeding 10 wt% and temperatures above 90 °C, significantly reducing surfactant performance and limiting their applicability in EOR operations14. One of the major obstacles in surfactant flooding is the adsorption of surfactants onto reservoir rock surfaces. This adsorption reduces the concentration of surfactants available for oil mobilization, thereby diminishing the overall efficiency and economic viability of the EOR process15,16. Factors such as the type of surfactant, reservoir temperature, salinity, and the mineralogical composition of the rock significantly influence the extent of surfactant adsorption17,18,19. The interaction between surfactants and reservoir rocks is primarily governed by the relative electrical charges of the surfactant molecules and the rock surfaces. Electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged surfactants and rock surfaces enhances adsorption, whereas like charges lead to electrostatic repulsion and reduced adsorption. Additionally, salinity and the ionic composition of the reservoir brine can substantially influence these interactions20,21. Adjustments to parameters such as pH, achieved through the addition of alkalis, can further modify rock surface charges and consequently alter surfactant adsorption behavior22,23. The types of ions and the salinity level can influence the adsorption of anionic surfactants on reservoir rocks. Increasing salinity compresses the electrical double layer, reducing the electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged surfactants and rock surfaces, thereby increasing adsorption. Additionally, the charge of the rock surface can alter upon contact with saline water, further affecting surfactant interactions24,25. Temperature plays a pivotal role in surfactant retention, with its influence greatly shaped by variables such as rock type, brine composition, and salinity levels26,27. For nonionic surfactants, increasing temperature often decreases the CMC initially due to enhanced hydrophobic interactions; however, at higher temperatures, the CMC may increase as system hydrophilicity decreases. For ionic surfactants, elevated temperatures reduce electrostatic repulsion between head groups, facilitating micelle formation at lower concentrations28,29,30. Zwitterionic surfactants have drawn significant attention due to their unique molecular structure, which combines anionic and cationic head groups. This dual nature imparts several advantages, including lower CMC, enhanced foam stability, and improved wettability modification. However, the injected solution properties such as salinity and pH, as well as reservoir temperature can influence on zwitterionic surfactants performance16,31,32. The adsorption behavior of C16DmCB on carbonate and sandstone rock surface was investigated. Adsorption was observed to follow the Frumkin isotherm for sandstone and the Sips isotherm for carbonate. Salinity was found to enhance adsorption, whereas the effects of alkalinity varied. Zeta potential measurements indicated that hydrophilic interactions were promoted. Spontaneous imbibition tests confirmed that oil-wet surfaces were effectively altered to water-wet, demonstrating the potential for improved oil recovery33. The performance of synthesized carboxybetaine-based zwitterionic surfactants with hydrophobic tails of 12, 14, 16, and 18 carbons in harsh reservoir conditions was evaluated. Surface tension measurements were conducted, revealing a direct relationship between increasing carbon chain length and the reduction in surface tension. The wettability of oil-wet surfaces was effectively altered to water-wet, with minimal surfactant loss reported. Additionally, more than 30% additional oil recovery was achieved through the injection of alkali-surfactant-polymer slugs into sand packs34. The adsorption of cocamidopropyl hydroxysultaine surfactants on Bedford limestone surfaces was analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography. The findings indicated that increased salinity enhanced surfactant adsorption, whereas elevated temperatures reduced adsorption35. The adsorption of a biobased zwitterionic surfactant on quartz surfaces at a temperature of 45 °C was also studied, with adsorption capacity measured at 0.43 mg/g-rock36. The adsorption of two types of zwitterionic surfactants on kaolinite surfaces was investigated. It was reported that increasing surfactant concentration led to higher adsorption, because of presence of strong attractive forces between the positively charged headgroups of the surfactants and the negatively charged kaolinite surface37.

Applying EOR techniques in real reservoirs is much harder than in labs. Lab experiments use uniform rock samples under controlled conditions, but real reservoirs are more complex. They have varying porosity, permeability, and fluid composition, which cause uneven fluid flow and chemical distribution. Brine in reservoirs also contains multivalent ions that make surfactants less effective than in lab settings. Scaling up EOR techniques is expensive and challenging. Surfactants are costly to produce, and their effectiveness reduces due to chemical degradation and adsorption. Field operations also face practical limits, like injection pressures or production disruptions38,39.

This study explored the adsorption characteristics of ZW4 on calcite surfaces through a comprehensive series of investigations. Initially, the impacts of salinity and temperature on the CMC of ZW4 were analyzed to understand the surfactant’s behavior under varying conditions. To further elucidate its behavior, detailed thermodynamic characterization of ZW4 micellization was conducted, involving calculations of the standard Gibbs free energy (ΔGm°), enthalpy (ΔHm°), and entropy (ΔSm°) of micelle formation in aqueous solutions. Beyond micellization, the study provided a systematic examination of critical environmental parameters such as ZW4 concentration, salinity, and pH and their impact on its adsorption behavior on calcite surfaces. Additionally, to better understand the equilibrium adsorption process of ZW4 in the presence of MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄, this research employed two-parameter adsorption models with three-parameter isotherm models for a more accurate depiction of ZW4 adsorption dynamics. Thermodynamic driving forces were also quantitatively assessed by calculating the standard Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔG°) for ZW4 on calcite. This integrated approach rigorously compared calculated ΔG° values with experimental data, while evaluating the proposed mechanism for salinity-induced adsorption enhancement. The findings offered deeper insights into the complex interactions governing ZW4 adsorption on calcite surface.

Materials and methods

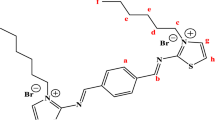

Surfactant

The zwitterionic surfactant, 3-(N, N-Dimethylmyristylammonio) propane sulfonate (ZW4), with a molecular weight of 363.60 g/mol, obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, was used in this study (Fig. 1).

Electrolyte

Electrolyte solutions were prepared using deionized water, into which MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄ were dissolved at concentrations of 0.01 M, 0.02 M, and 0.03 M. Both salts were supplied by Merck Company and were used as received, without undergoing further purification.

Rock sample

A carbonate rock sample was obtained from outcrops surrounding a southwestern Iranian oil field. The composition of the rock was analyzed using the X-ray Diffraction (XRD) technique, which revealed that calcite is the dominant mineral in the rock. The XRD pattern resulting from the analysis is shown in Fig. 2.

Zeta potential measurement

The Zetasizer Nano ZS from Malvern was used to measure the zeta potential of various solutions. This device operates based on the principle of Electrophoretic Light Scattering. For sample preparation, the rock was crushed and sieved, and the average particle size of the resulting powder used for zeta potential measurements was 3.26 μm, as shown in Fig. 3. Subsequently, 500 ppm of rock powder was mixed into the surfactant solution and stirred at 500 rpm for 6 h. All experiments were conducted at ambient pressure and a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C. Each test was performed in duplicate to ensure reliability, and the average values were reported. The accuracy of the measured zeta potential is ± 1 mV.

Adsorption measurement

Batch tests were conducted to investigate the adsorption process of ZW4 on calcite surfaces. Calcite powder, with a particle size of 180–250 micrometers, was sieved and subsequently washed with deionized water (DW) to remove impurities. The powder was then dried in an oven at 30 °C. Three grams of calcite powder were added to ZW4 solutions at various concentrations. The pH of each sample was adjusted to the desired value using NaOH to ensure consistent adsorption conditions, as pH strongly influences surfactant-calcite interactions. NaOH was carefully added to the solutions in small increments, with the pH continuously monitored during adjustment. Calcite-surfactant suspensions were stirred at 600 rpm for 24 h to achieve adsorption equilibrium. The temperature was carefully controlled to minimize thermal effects, and the pH was monitored throughout the experiment to ensure stability. After the stirring period, the final pH was recorded again to confirm its consistency.

Each suspension was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min to fully separate the calcite particles, leaving a clear supernatant. The ZW4 concentration in each supernatant was measured using UV-visible spectrophotometry, with a calibration curve employed to determine the surfactant concentrations in the solutions. Each adsorption test was conducted in triplicate, with a 5% error margin in the measurements. To construct an adsorption isotherm, data were collected across a range of initial ZW4 concentrations, plotting the amount of surfactant adsorbed per gram of calcite against the equilibrium concentration in the solution40. Various adsorption isotherm models were applied to better understand the adsorption process41,42. In the following sections, the commonly used adsorption isotherm models are discussed.

Langmuir isotherm

The Langmuir isotherm model describes monolayer adsorption on a finite number of uniform surface sites, assuming each site accommodates one molecule. It was originally developed for gas-solid interactions and is widely applied in adsorption studies. It can be expressed by41:

.

Where \(\:{q}_{e}\) is the amount of ZW4 at equilibrium temperature (mg/gr). \(\:{Q}_{m}\) represents the maximum adsorbed capacity (mg/gr). \(\:{K}_{L}\) is the Langmuir constant (L/mg). \(\:{C}_{eq}\) is the equilibrium concentration of the ZW4 in the solution (mg/L).

Freundlich isotherm

The Freundlich isotherm empirically describes non-uniform adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces, allowing multilayer adsorption with varying adsorption energies. The Freundlich Isotherm equation is as follows42:

.

Where \(\:{K}_{F}\) is the distribution coefficient and \(\:1/n\) measure of adsorption intensity, indicating surface heterogeneity.

Temkin isotherm

The Temkin isotherm accounts for adsorbent-adsorbate interactions, assuming adsorption heat decreases linearly with surface coverage, indicating energetic heterogeneity. This model is as follows43:

Where \(\:B\) is constant related to heat of sorption and \(\:A\) is Temkin isotherm equilibrium binding constant.

Redlich-peterson (R-P) isotherm

The Redlich-Peterson isotherm model describes solute adsorption from liquids onto solids, combining Langmuir’s monolayer assumptions and Freundlich’s heterogeneity. Its hybrid nature makes it versatile for modeling diverse adsorption systems with varying surface characteristics. It can be expressed by44:

.

Where \(\:{K}_{r}\) and \(\:\alpha\:\) are the Redlich-Peterson constant related to the adsorption capacity. \(\:\beta\:\) is the exponent that describes the heterogeneity of the surface (0 < β ≤ 1).

Sips isotherm

To study adsorption in systems characterized by heterogeneity, the Sips model proves to be highly effective, as it merges the principles underlying both the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms. It addresses the limitation of the Freundlich model, which cannot predict saturation at high adsorbate concentrations, by transitioning into Langmuir-like monolayer adsorption behavior at these higher concentrations due to the finite number of adsorption sites. The Sips adsorption model can be expressed by45:

The parameter \(\:{q}_{e}\) represents the amount of adsorbate retained on the surface at equilibrium, with \(\:{q}_{m}\) denoting the maximum adsorption capacity achievable under monolayer conditions. \(\:{K}_{s}\) defines the equilibrium constant specific to the Sips model, which measures adsorption affinity, while \(\:n\) characterizes the degree of surface heterogeneity. When \(\:n\) equals 1, the Sips model simplifies to the Langmuir isotherm, indicating a uniform surface. Conversely, values of \(\:n\) less than 1 reflect heightened surface heterogeneity.

Results and discussions

CMC measurement of ZW4

The Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) is the concentration at which surfactant molecules transition from existing as individual units to forming clusters called micelles. Below the CMC, the surfactant molecules remain dispersed, and increasing the concentration simply raises the number of individual molecules in the solution. Once the CMC is reached, the molecules begin to aggregate into micelles, leading to noticeable changes in the solution’s properties. Since the solution’s behavior differs significantly below and above the CMC, accurately determining the CMC of surfactants is essential. As shown in Fig. 4, the CMC of ZW4 was determined at 25 °C using equilibrium static surface tension measurements via the pendant drop method. Following a 1-minute stabilization period, a minimum value of 41.2 dynes/cm was observed at a concentration of 2000 ppm (5.6 mM). Initially, surfactant monomers adsorb at the Air-Solution Interface, reducing surface tension. However, beyond a certain concentration, the ASI becomes saturated, and no further reduction in surface tension occurs. This saturation point corresponds to the CMC. It is worth noting that each measurement was repeated three times, with an error of ± 0.2 dynes/cm.

Effect of salinity on ZW4 CMC

The CMC of the zwitterionic surfactant ZW4 was determined using surface tension measurements at ambient pressure and at temperature of 25 ± 1° C. as presented in Fig. 5. Micellization occurs when surfactant molecules self-assemble beyond a threshold concentration to minimize interfacial free energy. Surface tension analysis effectively identifies the transition from monomers to micelles.

In ionic surfactants, electrostatic repulsion between similarly charged head groups counteracts micelle formation, necessitating higher surfactant concentrations to overcome these repulsive forces and reach the CMC. The presence of electrolytes reduces these interactions via electrostatic shielding, where counterions in solution neutralize surface charges, thereby facilitating micellization at lower surfactant concentrations46.

To investigate the influence of salt addition on the CMC of ZW4, we selected MgSO4 and Na2SO4 at a fixed concentration of 0.01 M. Surface tension measurements were performed as the surfactant concentration increased up to 2500 ppm, a value chosen slightly above the expected CMC of ZW4 in DW. This upper limit ensured that the complete CMC transition could be captured in the presence of added salts, which are known to modulate the surfactant’s self-assembly behavior.

The results presented in Fig. 5 demonstrate that the addition of salts significantly decreased the CMC of ZW4, with MgSO4 exhibiting a more pronounced effect compared to Na2SO4. At a 0.01 M concentration of MgSO₄, the CMC of ZW4 decreased to 1300 ppm, whereas the same concentration of Na₂SO₄ resulted in a CMC reduction to 1700 ppm.

The observed reduction in CMC with electrolyte addition aligns with established theories of micellization in zwitterionic surfactant systems. Divalent ions, such as Mg2+, exert a stronger influence on reducing the CMC compared to monovalent ions due to their increased charge density and hydration characteristics. The more effective charge screening provided by Mg2+ ions reduce the electrostatic repulsion between surfactant molecules, enabling micellization to occur at lower concentrations.

Additionally, the salting-out effect observed with Mg2+ ions suggests that ion-specific interactions play a critical role in surfactant aggregation. The greater charge density of Mg2+ enhances the dehydration of surfactant head groups, promoting tighter molecular packing within micelles. In contrast, Na+, being monovalent, exhibits weaker charge screening and a less pronounced salting-out effect, resulting in a comparatively smaller reduction in the CMC.

In order to assess how different surfactant systems adsorb at interfaces, Gibbs adsorption isotherm could be employed. This approach provided values for \(\:{\varGamma\:}_{max}\), representing the maximum surface adsorption capacity, as well as \(\:{A}_{min}\), indicating the smallest average area occupied per individual surfactant molecule47,48. These parameters are illustrated in Eqs. (6) and (7), respectively.

.

Where \(\:{{\Gamma\:}}_{max}\) is maximum surface adsorption capacity in (mol/m²), \(\:{A}_{min}\) is area per molecule \(\:{(nm}^{2}/mol\)) γ is surface tension (N/m), C is surfactant concentration (mol/L), \(\:{\left(\frac{d\gamma\:}{d\text{ln}C}\right)}_{T}\) is the slope of surface tension vs. ln (concentration) in the linear region before CMC.

The adsorption and micellization behavior of surfactants, as well as their spontaneity, can be effectively analyzed through thermodynamic parameters. \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{mic}\), the standard Gibbs free energy change of micellization, quantifies the spontaneity of micelle formation. Meanwhile, \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{ads}\) represents the free energy change associated with the adsorption of surfactant molecules at interfaces, measuring the favorability of their transfer from the bulk solution to the interface. In other words, \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{mic}\) refers to the free energy of micellization, while \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{ads}\)corresponds to the free energy of adsorption47,49. These thermodynamic parameters are expressed by the following Eq.

.

Where \(\:{X}_{cmc}\) is mole fraction of ZW4 at CMC, \(\:R\) is universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹), \(\:T\) is temperature in Kelvin, \(\:{\pi\:}_{cmc}\) is the surface pressure at CMC obtained as \(\:{\pi\:}_{cmc}={\gamma\:}_{distilled\:water\:}-{\gamma\:}_{ZW4\:@\:CMC}\) .

The adsorption parameters and thermodynamic parameters of the ZW4 alone and in the presence of 0.01 M of Na2SO4 and 0.01 M of MgSO4 are presented in Table 1. The results showed that for the pure surfactant (ZW4), the \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{mic}\) is -12.90 kJ/mol and \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{ads}\) is -18.82 kJ/mol, indicating both processes are spontaneous under the conditions studied. The more negative value for \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{ads}\) compared to \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{mic}\) suggests that surfactant adsorption at interfaces is thermodynamically more favorable than self-assembly into micelles in the bulk phase. This is consistent with the general behavior of surfactants, as adsorption reduces the system’s free energy more significantly due to the reduction in surface tension.

When Na2SO4 is introduced, further lowering of both \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{mic}\) (-13.30 kJ/mol) and \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{ad}\) (-19.68 kJ/mol) is observed. Notably, the addition of MgSO4 leads to even more negative values for these parameters, with \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{mic}\) at -13.97 kJ/mol and \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{ads}\) at -20.33 kJ/mol. This trend reflects the pronounced influence of divalent cations (Mg2+) compared to monovalent cations (Na+) on surfactant aggregation and adsorption. Divalent salts can more effectively screen the electrostatic repulsion among surfactant headgroups, facilitating closer packing at interfaces and more efficient micellization. This effect is also evident in the decrease of \(\:{A}_{min}\) (the minimum surface area per molecule at the interface), which is smallest in the MgSO4 sample (0.271 nm2/mol), indicating tighter molecular packing. The comparison between the thermodynamic parameters of ZW4 and other zwitterionic surfactants is provided in the supplementary information, Table S.1.

Effect of temperature on CMC

Temperature significantly influences the CMC of surfactants by modulating molecular interactions4,50. In the presented study, the effect of temperature in the range of 10 °C to 90 °C on the CMC of the ZW4 was investigated, with results shown in Fig. 6. At 10 °C, the CMC was 2100 ppm, decreasing to 1900 ppm at 30 °C, and subsequently increasing to 2230 ppm at 90 °C.

As temperature increases, the CMC of ZW4 initially decreases and then increases. The initial decrease in CMC (10–30 °C) is attributed to a decrease in hydrophilicity and hydration of the hydrophilic group, which promotes micellization and allows for micelle formation at lower concentrations. However, with further temperature increase, the hydrophobic groups perturb the water structure, and the breakdown of structured water around the hydrophobic regions inhibits micellization51. Furthermore, at higher temperatures, the increase in thermal energy likely intensified electrostatic repulsion between the positive and negative head groups, counteracting aggregation and raising the CMC. As a result, higher temperatures lead to an increase in the CMC, as the hydrophobic interactions become more pronounced, necessitating higher surfactant concentrations to initiate micelle formation.

Understanding the thermodynamic properties of ZW4 micellization in water, such as the standard Gibbs free energy \(\:{(\varDelta\:G}_{m}^{0})\), the enthalpy \(\:{(\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0})\), and the entropy \(\:{(\varDelta\:S}_{m}^{0})\), provide insights into the balance between hydrophobic forces, interactions between the surfactant and water, and, for ionic surfactants, the repulsion between head groups51,52,53. By analyzing how the CMC varies with temperature, these thermodynamic quantities can be calculated. According to the phase separation model and the mass action model, the standard Gibbs free energy of micellization per mole of a surfactant monomer is as follows54:

.

where \(\:{\chi\:}_{CMC}\) is the mole fraction of surfactant in aqueous solution at the CMC, \(R = 8.314\:J/mol\, \cdot K\) and \(\:T\) is in Kelvin.

Use the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation the enthalpy (\(\:{\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}\)) is as follows:

.

The entropy (\(\:{\varDelta\:S}_{m}^{0}\)) of micellization can be calculated by the following formulas:

.

The calculated thermodynamic parameters of micellization of ZW4 is presented in Table 2.

The thermodynamic parameters of micellization for the ZW4 surfactant, which were derived from the variation of CMC with temperature, revealed significant insights into the ZW4 micelle formation process and its driving forces. The Gibbs free energy of micellization \(\:\left({\varDelta\:G}_{m}^{0}\right)\) was consistently negative across the studied temperature range, indicating that micellization occurred spontaneously under all conditions examined. This spontaneous nature was consistent with the general understanding of surfactant behavior, wherein surfactant molecules above the CMC aggregated to minimize the free energy of the system by reducing the unfavorable contact between hydrophobic tails and water46,55. The enthalpy changes of micellization \(\:\left({\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}\right)\), which were calculated from the temperature dependence of the mole fraction of surfactant at the CMC, exhibited a notable temperature dependence. At lower temperatures, \(\:\left({\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}\right)\) was positive, signifying an endothermic micellization process. This suggested that energy input was required to disrupt the structured hydrogen bonding network of water surrounding the hydrophobic chains, thereby facilitating micelle formation. As the temperature increased, \(\:{\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}\) decreased and eventually transitioned to negative values, indicating that micellization became exothermic at higher temperatures. This behavior reflected the weakening of water structure and hydrogen bonding with rising temperature, which reduced the energetic cost of micellization and, in some cases, released energy as micelles formed. At lower temperatures, micellization was observed to be endothermic \(\:({\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}>0)\); however, as the temperature increased, the process became exothermic \(\:({\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}<0)\);. The results indicated that the large negative Gibbs free energy of micellization was primarily attributed to a substantial positive entropy contribution, particularly at lower temperatures. As a result, micellization was concluded to be an entropy-driven process55.

The positive \(\:{\varDelta\:S}_{m}^{0}\) was attributed to the release of ordered water molecules from the hydration shells surrounding the hydrophobic tails during micelle formation. This liberation of water molecules increased the overall disorder of the system, which thermodynamically favored micellization. Additionally, the entropy gain reflected the increased rotational and translational freedom of surfactant molecules within the micelle interior compared to their solvated monomeric state. At intermediate temperatures, where \(\:{\varDelta\:H}_{m}^{0}\) approached zero or turned slightly negative, the contribution of entropy balanced the enthalpic changes, illustrating the enthalpy-entropy compensation phenomenon commonly reported in micellization thermodynamics.

The observed temperature dependence of these thermodynamic parameters aligned well with earlier literature reports on surfactants containing oxyethylene groups and similar structural features, where the CMC initially decreased with increasing temperature due to reduced hydrophilicity, but rose at higher temperatures as micellization became less favorable. This behavior reflected the complex interplay between hydrophobic interactions, the structural properties of water, and surfactant hydration29,56,57. The compensation effect between enthalpy and entropy changes ensured that \(\:{\varDelta\:G}_{m}^{0}\) remained negative and relatively stable across the studied temperature range, maintaining micelle formation as a thermodynamically favorable process56.

Surface charge of calcite

The ability of ZW4 to alter the wettability of the calcite surface is directly influenced by its adsorption onto the surface. Moreover, the extent of ZW4 adsorption on the calcite surface is strongly dependent on the surface charge of the calcite. Determining the calcite surface charge is vital for predicting and comprehending the behavior of ZW4 in this system.

To understand the surface charge properties of calcite, it is essential to study the equilibria between calcite/aqueous solution. Furthermore, zeta potential is a useful technique to examine the surface charge of calcite particles. Considering the both evaluation method mentioned above, in the following the surface charge of calcite is discussed.

According to the published data in the literature, the Point of Zero Charge (PZC) values in the range of 5.4–10.8 was documented for calcite58,59,60. In our study, as depicted in Fig. 7, the zeta potential of calcite powder in DW in different pH was measured and the PZC was found to be around 6.7.

Surveying the literature showed that some researchers reported a positive charge for the calcite surface61,62, while others reported negative values63,64. The differences in the reported values appear to depend on several parameters, such as the nature of the calcite rock, the types and concentrations of salts, and the pH of the solutions65,66. In our study, the pH of calcite in the DW was measured 8.13, 1.43 higher than the PZC of calcite (6.7), confirming the negative charge of calcite in the DW. The zeta potential also recorded − 16.4 mV.

This inconsistency in the reported charge of calcite by different researchers may be attributed to the complex process of calcite dissolution in aqueous solutions. The system’s controlling equilibrium reactions can be summarized as follows65,67:

.

Because the equilibrium constant of Eqs. 18 and 19 are very low, the amount of \(\:{Ca\:\left(OH\right)}^{+}\:\left(aq\right)\) and \(\:{Ca\:\left(OH\right)}_{2}\left(s\right)\) are very negligible and could be ignored. From the above equilibrium reactions, it was found that different ions with both positive and negative charges are produced by dissolution of calcite into the aqueous solutions which caused to not possible to predict the calcite surface charge accurately.

A study conducted on this subject indicates that the energy required for a calcium ion to detach from the crystal to an infinite distance resulting in the formation of a charged and isolated vacancy is lower than that required for a carbonate ion. Consequently, the probability of vacancy formation is higher for calcium than for carbonate ion. The removal of calcium ions from the calcite surface causes the surface charge to become negative68. The findings of our study were consistent with this explanation, as the measured negative zeta potential confirmed that the dissolution of calcite into the aqueous solution resulted in the release of calcium ions from the calcite surface.

Effect of ZW4 concentration on calcite surface charge

In this section, the effect of different concentrations of ZW4 on the surface charge of calcite was investigated through zeta potential measurements at ambient pressure and at temperature of 25 ± 1° C. The surface charge was evaluated for four different ZW4 concentrations: 1000, 1500, 2000, and 2500 ppm. The results, presented in Fig. 8, demonstrated that an increase in ZW4 concentration led to a more negative zeta potential. Specifically, at a concentration of 1000 ppm, the zeta potential was measured at -22.3 mV, and it further decreased to -30.8 mV at 2000 ppm. However, beyond the CMC of ZW4 (2000 ppm), the rate of increase in the negative zeta potential diminished, suggesting a saturation effect in ZW4 adsorption on the calcite surface.

Additionally, Fig. 8 illustrated the variation in pH with increasing ZW4 concentration. A slight decrease in pH was observed as the ZW4 concentration increased. This reduction in pH was attributed to the excessive adsorption of ZW4, which likely inhibited calcite dissolution, thereby reducing the release of carbonate ions into the solution. The pH of the DW was measured at 8.13, which gradually decreased to 7.94 in the presence of 2500 ppm ZW4.

Effect of salinity on surface charge of calcite

To investigate the effect of salinity on the surface charge of calcite, zeta potential measurements were performed at concentrations of 0.01 M, 0.02 M, and 0.03 M for both Na2SO4 and MgSO4. The ZW4 concentration was fixed to 2500 ppm. The corresponding data, including the pH values of the solutions, are provided in Fig. 9. All tests were conducted under ambient pressure and at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C.

The pH of solutions containing Na₂SO₄ was observed to be higher than that of solutions containing MgSO₄ (measurements were taken in the presence of calcite powder). Specifically, the pH values for Na₂SO₄ at concentrations of 0.01 M, 0.02 M, and 0.03 M were 8.03, 8.12, and 8.19, respectively. In contrast, the pH values for MgSO₄ at the same concentrations were 7.90, 7.83, and 7.79, respectively.

The dissolution of MgSO4 in DW results in a slight decrease in pH, making the solution marginally acidic, whereas Na2SO4 tends to slightly increase the pH, making the solution more basic. The dissolution of MgSO4 in water is represented by the following reaction:

.

Magnesium ions (Mg2+) are relatively small and highly charged, which can cause polarization of water molecules and a slight release of hydrogen ions (H+). The hydrolysis reaction of magnesium ions is as follows:

.

This hydrolysis reaction produces H⁺ ions, which decrease the pH, making the solution slightly acidic (pH < 7). However, the extent of this hydrolysis is relatively small. On the other hand, the dissolution of Na₂SO₄ in water, as represented by the equation:

.

It leads to the production of hydroxide ions (OH⁻), which slightly increases the pH of the solution. As noted in the previous section, dissolving calcite in DW increased the pH to 8.13. When Na₂SO₄ and MgSO₄ were added to the DW containing calcite powder, the final pH values and corresponding zeta potential measurements were summarized in Fig. 9. The results showed that, at all three concentrations of Na2SO4 and MgSO4, the pH values remained above the PZC of calcite (pH = 6.7), indicating that the calcite particles maintained a negative charge in all tested solutions. Additionally, the data revealed that the zeta potential of the Na₂SO₄ solution was more negative than that of the MgSO4 solution.

One of the most significant factors influencing the zeta potential is the charge density of the ions in the solution. Magnesium ions, due to their small size and high charge density, strongly interact with the negatively charged calcite surface, compressing the electrical double layer and reducing the negative calcite surface charge, which results in a less negative or neutral zeta potential. In contrast, sodium ions, being larger and lower in charge density, exert a weaker effect on the double layer, allowing the negative charge to remain stronger and resulting in a more negative zeta potential.

Furthermore, Mg²⁺ causes greater compression of the electrical double layer, reducing the thickness of the diffuse layer and shielding the surface charge more effectively than sodium ions. This compression diminishes repulsive forces, resulting in a decreased negative zeta potential.

Adsorption behavior of ZW4

Effect of ZW4 concentrations

The adsorption of surfactants on rock surfaces is influenced by key factors, including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, chemical interactions, electrostatic interactions, nonpolar interactions, and ion exchange69,70.

Figure 10 shows the amount of ZW4 adsorbed on the calcite surface at pH 8 in DW under ambient pressure and at a temperature of 25 ± 1 °C. The adsorption initially increased sharply, transitioned to a gentler slope, and plateaued at approximately 2500 ppm; 500 ppm higher than the CMC of ZW4. Each adsorption test was conducted in triplicate, with a 5% error margin in the measurements.

When the surfactant concentration exceeds its CMC, the behavior of the surfactant changes significantly. Below the CMC, surfactant molecules primarily exist as monomers, which adsorb onto the calcite surface, occupying available binding sites. As the concentration increases, more monomeric surfactant molecules are available, enhancing adsorption. Upon reaching the CMC (2000 ppm in this study), surfactant molecules begin to aggregate into micelles. At concentrations above the CMC, the micelles, being larger and aggregated, no longer adsorb onto the calcite surface because they cannot effectively interact with the surface sites. Consequently, the concentration of free surfactant molecules (monomers) remains constant, and the adsorption density stabilizes, resulting in a plateau. This behavior aligns with the pseudo-phase separation model, where excess surfactant above the CMC exists as micelles, and only the monomeric form continues to adsorb, leading to a stabilized adsorption density71,72. Maximum adsorption saturation was observed at 2500 ppm, where micelle formation predominated, diminishing the driving force for further adsorption. In the following sections, a concentration of 2500 ppm of ZW4 was chosen.

Effect of pH

The adsorption of ZW4 on the calcite surface was investigated across pH levels of 8, 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, and 10.0. The experiments were conducted at a constant ZW4 concentration of 2500 ppm, maintained under atmospheric pressure, with a temperature controlled at 25 ± 1 °C. Each adsorption test was conducted in triplicate, with a 5% error margin in the measurements.

In this study, the acidic pH range was not used because the tests performed in the acidic pH range yielded unreliable results. This issue arose because the pH values fluctuated during the experiments due to the equilibrium reaction between the acid and calcite40. This equilibrium reaction is as follows:

.

As the reaction progressed, the concentration of \(\:{H}^{+}\) ions gradually decreased, causing the pH of the system to shift from acidic to basic. For instance, it was reported that starting experiment with pH of 4 resulted in a final pH of approximately 7.5. The challenges associated with utilizing calcite under acidic conditions have also been documented by other researchers73.

At higher pH levels, the concentration of hydroxide ions \(\:{(OH}^{-})\) in the solution increases, altering the carbonate equilibrium on the calcite surface. According to reactions 14 and 15, elevated pH favors the formation of \(\:{CO}_{3}^{2-}\) and \(\:{HCO}_{3}^{-}\), which adsorb onto the calcite surface and significantly enhance its negative surface charge, as confirmed by Zeta potential measurements (Fig. 7).

ZW4, a zwitterionic surfactant, contains both a negatively charged sulfonate group \(\:\left(S{O}_{3}^{-}\right)\) and a positively charged dimethylammonium group \(\:\left({N}^{+}{\left({CH}_{3}\right)}_{2}\right)\). The sulfonate group is strongly acidic and remains largely unaffected by pH changes, as it does not undergo protonation or deprotonation reactions. Similarly, the dimethylammonium group, being a quaternary ammonium compound, maintains a permanently positive charge, independent of pH. As a result, the overall charge of the surfactant remains constant across the entire pH range, and ZW4 remains zwitterionic throughout.

As shown in Fig. 11, the amount of ZW4 adsorbed onto the calcite surface decreased as the pH increased. This is because, as the pH rises, the negative charge on the calcite surface increases, creating stronger electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged sulfonate group of ZW4 and the negative calcite surface. As a result, the interaction between ZW4 and the calcite surface becomes predominantly repulsive, reducing the surfactant’s affinity for the surface and leading to lower adsorption at higher pH values.

Effect of salinity

The effects of MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄ on the adsorption of ZW4 onto the calcite surface were investigated at three different concentrations (0.01 M, 0.02 M, and 0.03 M) under controlled conditions (pH 8 and 25 °C). Several factors affect the adsorption of surfactants onto rock surfaces, such as the rock’s surface charge, the surfactant’s electrical charge, and the characteristics of the electrolytes present. As shown in Fig. 12, increasing salt concentration enhanced ZW4 adsorption, with a consistently higher adsorption observed in the presence of MgSO₄ compared to Na₂SO₄. Each adsorption test was conducted in triplicate, with a 5% error margin in the measurements.

The adsorption of ZW4 surfactants onto calcite surfaces is predominantly dictated by electrostatic interactions between the surface charge of calcite and the charged functional groups of the surfactant. With a hydrophilic head composed of both positive and negative charges, the adsorption characteristics of ZW4 are strongly influenced by the charge properties of the calcite surface. The oppositely charged functional group of ZW4 is attracted to the calcite surface, facilitating adsorption. However, the same-charged group of ZW4 experiences an electrostatic repulsion, counteracting the attraction force and influencing the overall orientation of the surfactant molecules.

The orientation of ZW4 on the calcite surface is influenced by salinity, as it directly affects the surface charge of calcite. Under low salinity conditions, the calcite surface exhibited a higher negative charge, leading to the preferential adsorption of the positively charged ammonium group of ZW4 onto the surface, while the negatively charged sulfonate group is repelled. This results in a “V-shaped” molecular orientation (low packing density), where the surfactant molecules align with the positive ammonium group interacting with the surface and the sulfonate group extending outward. Figure 13 depicts schematics of ZW4 adsorption at different salinities.

The electrostatic characteristics of the calcite surface were strongly influenced by salinity levels, mainly due to the presence and interactions of different salt ions. Sulfate ions (SO₄²⁻), owing to their divalent nature and high charge density, interacted strongly with the positively charged regions of the calcite crystal lattice. This interaction reduced the positive surface charge of calcite and resulted in the development of a negative zeta potential, thereby significantly altering the calcite effective surface charge.

In contrast, monovalent sodium ions (Na+) and divalent magnesium ions (Mg2+) affected the negative surface charge of calcite through distinct mechanisms. Mg²⁺ ions, due to their high charge density and divalent nature, exhibited strong electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged calcite surface. These interactions facilitated specific adsorption, where Mg²⁺ ions directly bound to the calcite surface, effectively lowering its negative charge.

Experimental data indicated that the negative surface charge of calcite weakened more substantially in the presence of MgSO₄ compared to Na₂SO₄. Zeta potential measurements (Fig. 9) confirmed this observation, revealing that Mg²⁺ ions caused a greater reduction in the magnitude of the negative zeta potential than Na⁺ ions.

Furthermore, both Na2SO4 and MgSO4 ions were capable of screening the positive and negative head groups of ZW4. While sulfate ions (SO42-) exhibited similar effectiveness in screening the positively charged quaternary ammonium group of ZW4 for both salts, Mg2+ ions demonstrated a stronger ability to screen the negatively charged sulfonate group of ZW4.

The enhanced screening by Mg2+ ions, coupled with the greater reduction of calcite’s negative surface charge in the presence of MgSO₄, suggested that the repulsion force between the negatively charged sulfonate groups of ZW4 and the calcite surface decreased in the presence of MgSO₄. This decrease in repulsion facilitated stronger interactions between ZW4 and the calcite surface.

This reduction in electrostatic repulsion also allowed ZW4 molecules to transition from a “V-shaped” orientation (low packing density) to a more vertical “I-shaped” configuration (High packing density), where both the ammonium and sulfonate groups were involved in adsorption. This structural reorientation enhanced the molecular packing density and significantly increased the overall adsorption of ZW4 on calcite. A similar configuration of surfactant molecules on rock surfaces was previously proposed in the literature74,75. Consequently, as shown in Fig. 12, the adsorption density of ZW4 was observed to be higher in the presence of MgSO₄ compared to Na₂SO₄.

The stronger adsorption observed with MgSO₄ is primarily attributed to the higher charge density of Mg²⁺ ions, which effectively compress the electrical double layer and reduce the negative zeta potential of the calcite surface. However, ion-specific interactions, as described by the Hofmeister series, also play a crucial role in this behavior76. Mg2+, a kosmotropic ion, exhibits strong electrostatic interactions and a highly hydrated state, enabling it to structure water molecules and form stable complexes with the calcite surface. This kosmotropic nature enhances adsorption stability by facilitating tighter molecular packing of surfactant molecules. The kosmotropic influence of Mg²⁺ extends to the hydration dynamics of ZW4 surfactant molecules. By interacting tightly with the sulfonate groups of ZW4 and removing water from hydration shells, Mg2+ increases system entropy and promotes stronger surfactant adsorption on the calcite surface. Additionally, SO42-, another kosmotropic ion, further supports adsorption by screening the positively charged ammonium group of ZW4, reducing electrostatic repulsion and enabling a high-density, reorganized surfactant structure. In contrast, Na+, a chaotropic ion, exhibits weaker hydration forces and disrupts water structure. This results in less effective charge neutralization, hindered surfactant packing, and comparatively lower adsorption efficiency. Therefore, the enhanced adsorption observed with MgSO4 arises from the interplay of ion charge density, kosmotropic hydration effects, and Hofmeister-specific interactions, highlighting their critical role in optimizing surfactant adsorption thermodynamics beyond charge density effects alone77,78,79,80.

Schematic representation of ZW4 adsorption on calcite surfaces at different salinities of MgSO4 and Na2SO4: (A) 0.01 M, (B) 0.02 M, and © 0.03 M. Increasing salinity screens the charges of ZW4 head groups and reduces the negative charge of the calcite surface. This induces a transition in ZW4 molecular orientation, shifting from a ‘V-shaped’ configuration with lower packing density to a more vertical ‘I-shaped’ configuration with higher packing density.

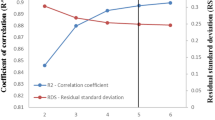

Equilibrium adsorption models

"Freundlich Isotherm" presents a comprehensive analysis of the adsorption models used to evaluate the equilibrium adsorption process. The quantitative results of curve fitting for MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄ at three concentrations (0.01 M, 0.02 M, and 0.03 M) are summarized in Table 3. To identify the most appropriate isotherm model, R² values from several adsorption isotherm models were compared, as illustrated in Fig. 14. The results show that, for both MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄, the Sips isotherm model consistently provided the best fit to the experimental data among all models evaluated.

To gain deeper insight into the equilibrium process, the adsorption characteristics of ZW4 on a calcite surface in the presence of MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄ were further analyzed using a range of adsorption models. These included the well-established two-parameter isotherms, Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin which are commonly used to describe adsorption mechanisms but differ fundamentally in their underlying assumptions and applicability81.

The results showed that the three-parameter models, Sips and RP provided a notably better fit to the experimental data compared to traditional two-parameter models. The enhanced flexibility of these three-parameter models allowed for a more accurate characterization of the complex adsorption mechanisms evident in systems with both homogeneous and heterogeneous surface interactions, especially under varying salinity conditions44,82.

Among the three-parameter models, the Sips isotherm consistently demonstrated the best agreement with the experimental data, as reflected by the highest R² values (Table 3). The Sips model effectively integrates features from both the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms, enabling accurate modeling of adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces at lower concentrations, while also transitioning to Langmuir-like saturation behavior at higher concentrations.

While the Sips model demonstrated the best fit for the adsorption data, as evidenced by its R² values (Table 3), it is important to consider the inherent limitations of the model. The Sips model, being a three-parameter approach, provides flexibility over simpler models by accounting for heterogeneous adsorption sites and non-uniform affinities. However, this increased flexibility introduces a risk of overfitting, particularly when precise experimental data are limited or contain noise.

A critical comparison of the Sips model with simpler, two-parameter models, Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin yields important practical insights. The Langmuir model postulates monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface with a finite number of identical sites, incorporating a clear saturation point, and is well-suited for uniform adsorption mechanisms41. The Freundlich model, by contrast, describes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces, allowing for a variable range of adsorption energies and potential multilayer formation, but lacks a defined adsorption maximum, thereby limiting its utility at high concentrations42. The Temkin model introduces the concept of diminishing heat of adsorption due to increasing surface coverage and recognizes the role of adsorbate–adsorbate interactions, representing systems with moderate surface heterogeneity43.

While both Langmuir and Freundlich models provided reasonably good fits to the data and offer the advantages of interpretability and simplicity, they fell short in accurately representing the observed experimental saturation behavior and the intricacies arising from surface heterogeneity and adsorbate interactions. The Temkin isotherm, although better at characterizing energy changes and molecular interactions, was surpassed by the predictive accuracy and flexibility of the Sips model. This best-fit capability is especially important for systems where adsorption mechanisms evolve with concentration or are influenced by multiple competing factors, as seen with ZW4 adsorption in the current study.

When evaluating predictive accuracy versus complexity, the Langmuir and Freundlich models showed reasonably high R² values but were consistently outperformed by the Sips model across all salinity levels for MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄ (Table 3; Fig. 14). The advantage of the Sips model lies in its ability to better accommodate the complex interplay between ion-specific interactions, surfactant packing density changes, and adsorption saturation effects near the critical micelle concentration. Simpler models, while less flexible, may still be suitable for preliminary assessments or when computational efficiency is prioritized.

By offering a refined and adaptable framework, RP and Sips isotherms significantly enhance the accuracy of adsorption studies, particularly in complex systems with heterogeneous surface interactions. Their ability to transition between different adsorption behaviors allows for a more precise representation of equilibrium conditions across diverse adsorption environments. As a result, these three-parameter models provide a more comprehensive and reliable approach for characterizing adsorption processes. The Sips isotherm model demonstrated a higher R2 value in comparison to the RP isotherm model.

Thermodynamics of ZW4 adsorption on calcite surface

Calculating the standard Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔG°) is essential for understanding and predicting surfactant adsorption behavior on calcite. The ΔG° value serves as a direct indicator of adsorption spontaneity: a negative ΔG° indicates that the process occurs naturally, while a positive value implies the need for external energy input. Furthermore, the magnitude of ΔG° reflects the favorability of adsorption, facilitating comparisons across different experimental conditions, such as varying concentrations of MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄83.

The standard Gibbs free energy of adsorption (ΔG°) can be calculated using the formula84:

where \(\:R\) is universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹), \(\:T\) is temperature in Kelvin, and K denotes the adsorption equilibrium constant.

In this study, all adsorption experiments were conducted at a constant temperature of 25 °C. The results in Table 4 indicated that ΔG° values were negative for all samples, confirming the spontaneity of adsorption of MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄ at various concentrations. More negative ΔG° values correspond to stronger thermodynamic driving forces, implying that higher salinity enhances adsorption. For instance, in the case of MgSO₄, ΔG° decreased from − 12.83 kJ/mol at 0.01 M to -14.19 kJ/mol at 0.03 M, demonstrating increased spontaneity at higher salt concentrations. A similar trend was observed for Na₂SO₄.

Comparisons between the two salts revealed that MgSO₄ consistently exhibited more negative ΔG° values than Na₂SO₄ at equivalent concentrations. This suggests that MgSO₄ is more favorably adsorbed onto the calcite surface under the studied conditions.

These findings are consistent with the experimental data and align with the hypothesized mechanism of adsorption enhancement due to salinity. As discussed in Sect. 4.3.3 (Effect of Salinity), increasing the salinity reduced electrostatic repulsion, facilitating a transition of ZW4 molecules from low to high packing density on the calcite surface. This structural reorganization allowed both the ammonium and sulfonate groups of ZW4 to contribute to adsorption, thereby increasing the molecular packing density and significantly enhancing overall adsorption.

Conclusion

This research focused on examining how ZW4 interacts with calcite surfaces through a series of detailed analyses. The study began by assessing how salinity and temperature impacted the CMC of ZW4, offering insights into the surfactant’s behavior under different environmental conditions. Subsequently, experiments investigated the surface charge of calcite, aiming to determine how variations in salinity and surfactant concentration influenced its characteristics. The adsorption behavior of ZW4 was also extensively analyzed, with particular attention given to the roles of pH, salinity, and surfactant concentration in the adsorption process. To deepen the understanding of the observed trends, various theoretical models were applied to interpret the equilibrium adsorption data. The collective findings from these analyses have led to the following conclusions:

-

1.

MgSO₄ is more effective than Na₂SO₄ at reducing the CMC of ZW4. This is because the divalent Mg²⁺ ions provide stronger electrostatic screening and enhanced salting-out effects, which promote tighter micelle packing.

-

2.

The adsorption and micellization of the ZW4 surfactant are spontaneous and thermodynamically favorable, with adsorption being more energetically favorable than micellization. The presence of electrolytes, particularly divalent Mg²⁺ ions, significantly enhances these processes by reducing electrostatic repulsion and enabling tighter molecular packing at interfaces.

-

3.

The CMC of ZW4 decreases between 10 and 30 °C due to reduced hydrophilicity, which favors micellization; however, above 30 °C, the CMC increases.

-

4.

Thermodynamic analysis revealed that ZW4 micellization is a spontaneous, entropy-driven process, with enthalpy-entropy compensation ensuring thermodynamic favorability across a wide temperature range.

-

5.

Increasing ZW4 concentration makes the calcite surface more negatively charged, but beyond the CMC, the rate of increase in negative zeta potential slows, indicating adsorption saturation.

-

6.

The zeta potential of calcite powder in DW in different pH was measured and the PZC was found to be around 6.7.

-

7.

ZW4 adsorption on calcite decreases at higher pH due to enhanced negative charge on calcite, which increases electrostatic repulsion with ZW4’s sulfonate group and reduces surfactant affinity.

-

8.

Increasing salinity enhanced adsorption, transitioning from a “V-shaped” orientation (low packing density) to a more vertical “I-shaped” configuration (high packing density), with MgSO₄ demonstrating a greater effect than Na₂SO₄, attributed to its stronger ability to neutralize surface charge.

-

9.

The three-parameter models, RP and Sips models were identified as effective for adsorption analysis, with the Sips model offering greater versatility and a better fit based on R² values across varying adsorption conditions for MgSO₄ and Na₂SO₄.

Data availability

All data will be available on academic request from the corresponding author.

References

Al-Azani, K. et al. Oil recovery performance by surfactant flooding: a perspective on multiscale evaluation methods. Energy Fuels. 36 (22), 13451–13478 (2022).

Chowdhury, S. et al. Comprehensive review on the role of surfactants in the chemical enhanced oil recovery process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61 (1), 21–64 (2022).

Yuan, C. D. et al. Effects of interfacial tension, emulsification, and surfactant concentration on oil recovery in surfactant flooding process for high temperature and high salinity reservoirs. Energy Fuels. 29 (10), 6165–6176 (2015).

Karnanda, W. et al. Effect of temperature, pressure, salinity, and surfactant concentration on IFT for surfactant flooding optimization. Arab. J. Geosci. 6, 3535–3544 (2013).

Hou, B. et al. Mechanism of wettability alteration of an oil-wet sandstone surface by a novel cationic gemini surfactant. Energy Fuels. 33 (5), 4062–4069 (2019).

Druetta, P. & Picchioni, F. Surfactant flooding: the influence of the physical properties on the recovery efficiency. Petroleum 6 (2), 149–162 (2020).

Kesarwani, H. et al. Anionic/nonionic surfactant mixture for enhanced oil recovery through the investigation of adsorption, interfacial, rheological, and rock wetting characteristics. Energy Fuels. 35 (4), 3065–3078 (2021).

Salager, J. L. Surfactants types and uses. FIRP Bookl., 300. (2002).

Hou, B. et al. Wettability alteration of oil-wet carbonate surface induced by self-dispersing silica nanoparticles: mechanism and monovalent metal ion’s effect. J. Mol. Liq. 294, 111601 (2019).

Nagy, R. et al. Selection method of surfactants for chemical enhanced oil recovery. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 5 (02), 121 (2015).

Yao, Y., Wei, M. & Kang, W. A review of wettability alteration using surfactants in carbonate reservoirs. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 294, 102477 (2021).

ShamsiJazeyi, H., Verduzco, R. & Hirasaki, G. J. Reducing adsorption of anionic surfactant for enhanced oil recovery: part II. Applied aspects. Colloids Surf., A. 453, 168–175 (2014).

Zulkifli, N. N. et al. Evaluation of new surfactants for enhanced oil recovery applications in high-temperature reservoirs. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 10, 283–296 (2020).

Da, C. et al. Carbon dioxide/water foams stabilized with a zwitterionic surfactant at temperatures up to 150 C in high salinity Brine. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 166, 880–890 (2018).

Bashir, A., Haddad, A. S. & Rafati, R. A review of fluid displacement mechanisms in surfactant-based chemical enhanced oil recovery processes: analyses of key influencing factors. Pet. Sci. 19 (3), 1211–1235 (2022).

Gbadamosi, A. et al. Static Adsorption of Novel Synthesized Zwitterionic Surfactants on Carbonates (Energy & Fuels, 2024).

Durán-Álvarez, A. et al. Experimental–theoretical approach to the adsorption mechanisms for anionic, cationic, and zwitterionic surfactants at the calcite–water interface. Langmuir 32 (11), 2608–2616 (2016).

Zhong, X. et al. Comparative study on the static adsorption behavior of zwitterionic surfactants on minerals in middle Bakken formation. Energy Fuels. 33 (2), 1007–1015 (2019).

Hou, B. et al. Wettability alteration of an oil-wet sandstone surface by synergistic adsorption/desorption of cationic/nonionic surfactant mixtures. Energy Fuels. 32 (12), 12462–12468 (2018).

Kalam, S. et al. A review on surfactant retention on rocks: mechanisms, measurements, and influencing factors. Fuel 293, 120459 (2021).

Aminian, A. & ZareNezhad, B. Wettability alteration in carbonate and sandstone rocks due to low salinity surfactant flooding. J. Mol. Liq. 275, 265–280 (2019).

Mohammed, I. et al. Surface charge investigation of reservoir rock minerals. Energy Fuels. 35 (7), 6003–6021 (2021).

Mahani, H. et al. The effect of salinity, rock type and ph on the electrokinetics of carbonate-brine interface and surface complexation modeling. in SPE Reservoir Characterisation and Simulation Conference and Exhibition? SPE. (2015).

Azam, M. R. et al. Static adsorption of anionic surfactant onto crushed Berea sandstone. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 3, 195–201 (2013).

Kalam, S. et al. Surfactant adsorption isotherms: A review. ACS Omega. 6 (48), 32342–32348 (2021).

Ziegler, V. M. & Handy, L. L. Effect of temperature on surfactant adsorption in porous media. Soc. Petrol. Eng. J. 21 (02), 218–228 (1981).

Belhaj, A. F. et al. Static adsorption evaluation for anionic-nonionic surfactant mixture on sandstone in the presence of crude oil at high reservoir temperature condition. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 25 (02), 261–272 (2022).

Kumar, S. & Mandal, A. Thermodynamics of micellization, interfacial behavior and wettability alteration of aqueous solution of nonionic surfactants. Tenside Surfactants Detergents. 54 (5), 427–436 (2017).

Mohajeri, E. & Noudeh, G. D. Effect of temperature on the critical micelle concentration and micellization thermodynamic of nonionic surfactants: polyoxyethylene Sorbitan fatty acid esters. J. Chem. 9 (4), 2268–2274 (2012).

Khoshnood, A., Lukanov, B. & Firoozabadi, A. Temperature effect on micelle formation: molecular thermodynamic model revisited. Langmuir 32 (9), 2175–2183 (2016).

Kamal, M. S., Shakil Hussain, S. M. & Fogang, L. T. A zwitterionic surfactant bearing unsaturated tail for enhanced oil recovery in high-temperature high‐salinity reservoirs. J. Surfactants Deterg. 21 (1), 165–174 (2018).

Lian, P. et al. Effects of zwitterionic surfactant adsorption on the component distribution in the crude oil droplet: A molecular simulation study. Fuel 283, 119252 (2021).

Kumar, A. & Mandal, A. Critical investigation of zwitterionic surfactant for enhanced oil recovery from both sandstone and carbonate reservoirs: adsorption, wettability alteration and imbibition studies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 209, 115222 (2019).

Kumar, A. & Mandal, A. Characterization of rock-fluid and fluid-fluid interactions in presence of a family of synthesized zwitterionic surfactants for application in enhanced oil recovery. Colloids Surf., A. 549, 1–12 (2018).

Nieto-Alvarez, D. A. et al. Adsorption of zwitterionic surfactant on limestone measured with high-performance liquid chromatography: micelle–vesicle influence. Langmuir 30 (41), 12243–12249 (2014).

Chen, Z. Z. et al. A thermal-stable and salt-tolerant biobased zwitterionic surfactant with ultralow interfacial tension between crude oil and formation Brine. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 181, 106181 (2019).

Lv, W. et al. Static and dynamic adsorption of anionic and amphoteric surfactants with and without the presence of alkali. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 77 (2), 209–218 (2011).

Syed, F. I., Dahaghi, A. K. & Muther, T. Laboratory to field scale assessment for EOR applicability in tight oil reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 19 (5), 2131–2149 (2022).

Akita, E. et al. A systematic approach for upscaling of the EOR results from lab-scale to well-scale in liquid-rich shale plays. in SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference? SPE. (2018).

Monfared, A. D. et al. Adsorption of silica nanoparticles onto calcite: equilibrium, kinetic, thermodynamic and DLVO analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 281, 334–344 (2015).

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40 (9), 1361–1403 (1918).

Freundlich, H. Über die adsorption in lösungen. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 57 (1), 385–470 (1907).

Tempkin, M. & Pyzhev, V. Kinetics of ammonia synthesis on promoted iron catalyst. Acta Phys. Chim. USSR. 12 (1), 327 (1940).

Redlich, O. & Peterson, D. L. A useful adsorption isotherm. J. Phys. Chem. 63 (6), 1024–1024 (1959).

Sips, R. On the structure of a catalyst surface. J. Chem. Phys. 16 (5), 490–495 (1948).

Gerola, A. P. et al. Micellization and adsorption of zwitterionic surfactants at the air/water interface. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 32, 48–56 (2017).

Zdziennicka, A. & Jańczuk, B. Thermodynamic parameters of some biosurfactants and surfactants adsorption at water-air interface. J. Mol. Liq. 243, 236–244 (2017).

Qi, L. et al. Synthesis and physicochemical investigation of long Alkylchain betaine zwitterionic surfactant. J. Surfactants Deterg. 11, 55–59 (2008).

Kamil, M. & Siddiqui, H. Experimental study of surface and solution properties of gemini-conventional surfactant mixtures on solubilization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. Model. Numer. Simul. Mater. Sci. 3 (04), 17 (2013).

Mahmood, M. E. & Al-Koofee, D. A. Effect of temperature changes on critical micelle concentration for tween series surfactant. Glob J. Sci. Front. Res. Chem., 13(1). (2013).

Di Michele, A. et al. Effect of head group size, temperature and counterion specificity on cationic micelles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 358 (1), 160–166 (2011).

Basílio, N. & Garcia-Rio, L. Calixarene‐Based surfactants: Conformational‐Dependent solvation shells for the alkyl chains. ChemPhysChem 13 (9), 2368–2376 (2012).

Prausnitz, J. M., Lichtenthaler, R. N. & De Azevedo, E. G. Molecular Thermodynamics of fluid-phase Equilibria (Pearson Education, 1998).

Hiemenz, P. C. & Rajagopalan, R. Principles of Colloid and Surface Chemistry, Revised and Expanded (CRC, 2016).

Floriano, M. A., Caponetti, E. & Panagiotopoulos, A. Z. Micellization in model surfactant systems. Langmuir 15 (9), 3143–3151 (1999).

Moghaddam, H. M., Dehghannoudeh, G. & Basir, M. Z. Evaluation the thermodynamic behavior of nonionic polyoxyethylene surfactants against temperature changes. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci., 29(2). (2016).

Zajac, J. et al. Thermodynamics of micellization and adsorption of zwitterionic surfactants in aqueous media. Langmuir 13 (6), 1486–1495 (1997).

Somasundaran, P. & Agar, G. E. The zero point of charge of calcite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 24 (4), 433–440 (1967).

Lafhaj, Z., Filippov, L. & Filippova, I. Improvement of calcium mineral separation contrast using anionic reagents: electrokinetics properties and flotation. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing. (2017).

Siffert, D. & Fimbel, P. Parameters affecting the sign and magnitude of the eletrokinetic potential of calcite. Colloids Surf. 11 (3–4), 377–389 (1984).

Karimi, M. et al. Mechanistic study of wettability alteration of oil-wet calcite: the effect of magnesium ions in the presence and absence of cationic surfactant. Colloids Surf., A. 482, 403–415 (2015).

Al Mahrouqi, D., Vinogradov, J. & Jackson, M. D. Zeta potential of artificial and natural calcite in aqueous solution. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 240, 60–76 (2017).

Pourchet, S. et al. Chemistry of the calcite/water interface: influence of sulfate ions and consequences in terms of cohesion forces. Cem. Concr. Res. 52, 22–30 (2013).

Fenter, P. et al. Surface speciation of calcite observed in situ by high-resolution X-ray reflectivity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 64 (7), 1221–1228 (2000).

Somasundaran, P., Amankonah, J. O. & Ananthapadmabhan, K. Mineral—solution equilibria in sparingly soluble mineral systems. Colloids Surf. 15, 309–333 (1985).

Mohammed, I. et al. Calcite–Brine Interface and its Implications in Oilfield Applications: Insights from Zeta Potential Experiments and Molecular Dynamics Simulations36p. 11950–11961 (Energy & Fuels, 2022). 19.

Eriksson, R., Merta, J. & Rosenholm, J. B. The calcite/water interface: I. Surface charge in indifferent electrolyte media and the influence of low-molecular-weight polyelectrolyte. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 313 (1), 184–193 (2007).

Cygan, R. T. et al. Atomistic models of carbonate minerals: bulk and surface structures, defects, and diffusion. Mol. Simul. 28 (6–7), 475–495 (2002).

ShamsiJazeyi, H., Verduzco, R. & Hirasaki, G. J. Reducing adsorption of anionic surfactant for enhanced oil recovery: part I. Competitive adsorption mechanism. Colloids Surf., A. 453, 162–167 (2014).

Somasundaran, P. & Zhang, L. Adsorption of surfactants on minerals for wettability control in improved oil recovery processes. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 52 (1–4), 198–212 (2006).

Shinoda, K. & Hutchinson, E. Pseudo-phase separation model for thermodynamic calculations on micellar solutions1. J. Phys. Chem. 66 (4), 577–582 (1962).

Perger, T. M. & Bešter-Rogač, M. Thermodynamics of micelle formation of alkyltrimethylammonium chlorides from high performance electric conductivity measurements. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 313 (1), 288–295 (2007).

Martinez-Luevanos, A., Uribe-Salas, A. & Lopez-Valdivieso, A. Mechanism of adsorption of sodium dodecylsulfonate on celestite and calcite. Miner. Eng. 12 (8), 919–936 (1999).

Jian, G. et al. Characterizing adsorption of associating surfactants on carbonates surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 513, 684–692 (2018).

Li, N. et al. Adsorption behavior of betaine-type surfactant on quartz sand. Energy Fuels. 25 (10), 4430–4437 (2011).

Parsons, D. et al. Why direct or reversed hofmeister series? Interplay of hydration, non-electrostatic potentials, and ion size. Langmuir 26 (5), 3323–3328 (2010).

Lo Nostro, P. & Ninham, B. W. Hofmeister phenomena: an update on ion specificity in biology. Chem. Rev. 112 (4), 2286–2322 (2012).

Kang, K. C. et al. Seawater desalination by gas hydrate process and removal characteristics of dissolved ions (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, B3+, Cl–, SO42–). Desalination 353, 84–90 (2014).

Gibb, C. L. & Gibb, B. C. Anion binding to hydrophobic concavity is central to the salting-in effects of hofmeister chaotropes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (19), 7344–7347 (2011).

Parsons, D. F. et al. Hofmeister effects: interplay of hydration, nonelectrostatic potentials, and ion size. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13 (27), 12352–12367 (2011).

Foo, K. Y. & Hameed, B. H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 156 (1), 2–10 (2010).

Wu, F. C. et al. A new linear form analysis of Redlich–Peterson isotherm equation for the adsorptions of dyes. Chem. Eng. J. 162 (1), 21–27 (2010).

Xu, Z., Yang, X. & Yang, Z. On the mechanism of surfactant adsorption on solid surfaces: free-energy investigations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 112 (44), 13802–13811 (2008).

Adamson, A. W. & Gast, A. P. Physical Chemistry of SurfacesVol. 150 (Interscience publishers New York, 1967).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Armin BazyariExperiments, Writing, Conceptualization, AnalysisAbdolnabi HashemiConceptualization, SupervisionBahram Soltani SoulganiConceptualization, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bazyari, A., Hashemi, A. & Soulgani, B.S. Experimental and theoretical investigation of zwitterionic surfactant adsorption on calcite for enhanced oil recovery. Sci Rep 15, 22730 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05707-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05707-5