Abstract

This paper evaluates the use of impedance spectroscopy combined with artificial intelligence. Both technologies have been widely used in food classification and it is proposed a way to improve classifications using recurrent neural networks that treat the impedance data series at different frequencies as a time series, with the intention of improving the identification of alpha and beta dispersions that are fundamental for the determination of food quality. This proposal in addition to being demonstrated its validity in the detection of YAKE on frozen tuna loins, is fully implemented on a low power FPGA device that allows the classification at the edge by means of a portable equipment that allows its application in food distribution chains with high energy efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Impedance spectroscopy is an instrumentation technique that measures the complex electrical impedance of a biological system when excited at different frequencies. Due to its electrical nature, the physiological behavior and state of a biological component directly affect its impedance. For this reason, an accurate measurement of the impedance of a biological system provides information about variations in internal physiological processes. Impedance spectroscopy is a non-invasive, fast, low-cost, and portable technology. Because of these properties, it is a perfect technique for application in industry to measure food quality, healthcare, and biomedicine. The technique has been successfully applied in different studies. In the food industry, it has been used for quality inspection in fruit1,2,3, fish and meat4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, and beverages14,15.

One of the current challenges of impedance spectroscopy is the adaptation of this technique to industrial environments. To do so, the technique must be fast, have low power consumption, be adaptable to detect different quality parameters in various foods, and be easily upgraded to improve detection with new algorithms.

The method used to conduct the measurements is impedance or dielectric spectroscopy. This approach allows us to determine the electrical properties of electron flow through a medium. An electron flow induces electrical and magnetic interactions, which are governed by Maxwell’s equations. This project aims to use low-frequency interactions in the band between Hz and MHz (more specifically, in the HF band). The fundamental physical property through which the electrical interaction of an electron flow with matter is described is the permittivity (\(\varepsilon\)), a vectorial physical property (since it describes the interactions of the electric field in one direction with respect to its polarity), which can be described as a complex number, where its real part is the dielectric constant (\(\varepsilon^{\prime}\)) and its imaginary part is the loss factor (\(\varepsilon^{\prime\prime}\)). The dielectric constant represents the proportion of electrical energy that is stored when the medium is oriented with respect to the direction of the field, and the loss factor represents the displacement of the field induced by the transformations of electrical energy into other energies, by collisions and frictions between molecules. At frequencies between Hz and MHz, orientation phenomena occur. These phenomena identify, together with conductivity, the dielectric behavior of biological systems.

Alpha (\(\alpha\)) scattering, also called counterion, is induced by the orientation of mobile charges in the dielectric medium. In this scattering, relaxation of molecules with ionic strength and mobility is found. In muscle systems, everything from biologically active electrolytes to charged weak acids is found. Beta (\(\beta\)) scattering covers a wide range of the spectrum, from kHz to MHz, and describes all interactions with fixed or low-mobility charges found in the dielectric medium. This dispersion is further divided into two frequency bands. On the one hand, there are interactions in the kHz range, which encompass interactions with charges belonging to structural macromolecules that make up the solid phase of the system, such as proteins. In the higher energy range, MHz, the interactions of charges associated with the surface tension of the solid surfaces in contact with the fluid medium. This phenomenon is called Maxwell-Wagner.

Structure of instrument

There are a multitude of impedance spectroscopy systems, also known as dielectric spectroscopy systems or bioimpedance measurement systems16,17. These systems are basically composed of five components:

-

Stimulus generation block: The stimuli used to perform the measurements can be of different types:

-

Simple tones at different frequencies that provide impedance measurements with good signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), but are slow when there are measurements with many components at low frequency.

-

Complex signals that improve the measurement time but generate a worse SNR. Among these methods,chirp-type signals or multisine signals are generated18,19.

-

-

Stimulus injection block: This block is composed of a current controlled source. The injection signal is generated digitally in the stimulus generation block. This signal attacks a DAC that generates an analog signal in voltage. The signal injected into the sample is current. For this, a controlled current source is required.

-

Sensor block: Depending on the sample to be analyzed, the system will make use of a certain type of sensor. In an impedance spectrometry system, the type of sensor will determine the field distribution over the sample, and therefore the information received.

-

Results measurement block: In this block, the voltage and current results generated in the sample after excitation must be measured. This stage is composed of a signal adaptation block and two ADCs that measure signals proportional to the voltage and current of the sample while it is excited.

-

Data Analysis Segment: Using signal processing techniques and with knowledge of the excitation source and recorded signals, the impedance spectrum can be determined. Additionally, with an understanding of the sensors’ geometry and arrangement, permittivity can be derived through processing20. The processing block’s role includes handling the measured data, identifying the sample’s characteristics, and forecasting its condition. Data processing can be performed in real time on the acquisition system or remotely on a PC that receives the measurements from the acquisition system. The processing in the measurement system enables real-time analysis, to perform new measurements based on these results automatically, or to make decisions with high response speed (such as classifying the sample in a shorter time based on the results). On the other hand, the type of processing that can be carried out on a control PC may be more complex and precise, due to the greater computing power, but cannot be performed in real-time.

AI at the edge

In the data processing block, an essential addition is made: the incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI). With explosive growth in the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to address a wide range of problems, information technology and semiconductor companies have rushed to develop electronics platforms that provide adequate performance with acceptable power expenditure. So far, most of the attention and investment has been directed towards “Cloud AI” but progressively the feature of being able to perform the computations derived from the application of artificial intelligence in the closest possible context to the sensor or instrument used and as autonomously as possible to cloud resources is being determined as essential. Given the severe constraints that govern sensing devices in terms of efficiency, robustness, and cost, it is evident that bringing artificial intelligence to these levels (“Edge”) requires deep innovation at all computational levels from the application (software) to the level closest to the hardware.

There are multiple definitions of edge computing. One of the most widely adopted definitions is that of21, which states that it brings computations closer to the edge of the network, that is, where the data originate. There are several reasons for adopting this concept, but perhaps the clearest one is that the massive application of artificial intelligence can lead to an increasing volume of data to be transmitted, unless this type of solution is applied, which would generate higher network performance22 since it is not necessary to transport data. Then, “AI at the Edge” is the use of AI in real-world devices. Referring to the practice of performing AI computations near users at the edge of the network instead of a centralized location, such as a cloud service provider’s data center or an enterprise’s private data warehouse23 . With the scope of the Internet, a hospital, factory, shopping malls, traffic signals, food distribution warehouses, customs, etc. are considered the edge.

Models used in deep learning are often relatively computationally expensive and problematic to run in real time in energy and computationally constrained environments. To do so, as indicated in the previous paragraph, it must be used specialized hardware, the so-called AI Accelerators. The term AI Accelerators encompasses a wide variety of different devices that use different technologies. In this case, the accelerators will be implemented specifically using existing FPGA logic resources and the design method will be based primarily on HDL (as Verilog) in the first stages of data processing, matching the data processing to the characteristics with which the acquired signals reach our AD data converters, combined with the use of high-level synthesizers (HLS).

Artificial intelligence has been successfully applied to impedance spectroscopy data for classification tasks. Recently, studies have used these techniques to improve the classification of storage temperature for mandarin24, tissue classification25, to estimate water stress in tomato plants26 and to the swift identification of beef quality27.

Developing AI at the edge capabilities on impedance spectroscopy systems will increase the number of characteristics that can be detected in real time when impedance measurement is performed.

In the present experiment, a new impedance spectroscopy system based on SoC FPGAs is proposed that is highly configurable and portable, with the possibility of being configured in wireless mode, and with a high capacity for real-time signal processing. This system must be able to perform several simultaneous measurements. At the same time, it will be designed to be scalable, joining several systems and increasing the number of measurements to cover a larger area. Real-time processing of these measurements is essential to enhance the precision of the recordings. The system will have several acquisition channels, independent of those used for impedance measurement, to acquire additional information from the measurement, such as humidity, pressure, temperature, data that will support the processing blocks when drawing conclusions. It will also have outputs for system control, and in its final version it should perform the classification task fully autonomously by means of a learning machine that performs the appropriate inference with the lowest possible latency.

The first published attempts to develop a low-cost wide-spectrum impedance analyzer were in 201028,29. They were based on the AD5933 integrated circuit (Analog Devices). Since then, multiple strategies have been developed to increase the amplitude, frequency, and impedance ranges, as well as the accuracy and user experience, among other limitations of AD593330,31,32. FPGAs have also previously been used in the development of impedance spectroscopy, demonstrating in different studies the need for an external analog interface for amplifications, calibration, conversions, and filtering33,34. Both devices have their weakest point in their adaptation in the Data Processing Block, and more specifically in the incorporation of AI. At the other extreme, other low-cost devices that are perfectly adapted to take on AI processing exist(Nvidia Jetson, Google Coral, Raspberry Pi, HPE Edgeline) have shortcomings in the generation and acquisition and sensing blocks. In summary, each method has its own advantages and disadvantages. This study aims to optimize the use of the FPGA’s logical resources to integrate classification tasks directly within the sensor.

Detecting YAKE in Tuna

The global size of the tuna market was valued at USD 41.94 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow from USD 42.96 billion in 2024 to USD 54.45 billion in 2032, showing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.01% during the forecast period.

Europe is positioned as a leader in the tuna sector, reaching a market value of US $12.9 million in 2021. This dominance is attributed to high per capita consumption of fish and seafood, coupled with a well-organized fishing industry. Tuna accounts for approximately 10 percent of total seafood consumption in Europe in 2022.

Tuna is considered one of the most important and commercially valuable fish and is an essential part of the marine ecosystem. Commercial tuna fishing is a key part of the blue economy, and six varieties of this fish are considered important, among others: southern bluefin tuna, skipjack, bigeye, Atlantic, yellowfin and Pacific bluefin. In recent years, the seafood industry has observed new trends in consumer consumption patterns. People around the world are opting for healthy and convenient foods, which has significantly boosted demand for protein-rich foods like tuna.

The Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 of the United Nations calls for accelerated action to reduce food loss and waste, with a goal of halving it by 2030. Food loss and waste are defined as “a reduction in the quantity and quality of food” and refer to “food lost or wasted in the part of food chains leading to edible products intended for human consumption.” In the context of fish as food for more than 3.3 billion people worldwide, fish provides 20 percent of their average per capita intake of animal protein, making fishing central to achieving food security35. However,36 is a highly perishable food, particularly vulnerable to loss. In general, 30–35% of the production of fish and aquaculture is estimated to be lost or wasted annually.

The tuna industry is a particularly important example of the potential benefits that can be achieved by reducing seafood waste. Tuna (family Scombridae, tribe Thunnini) are important species, as they not only play an important role in the ocean ecosystem as top predators, but are also an affordable source of high-quality, nutritious protein.

Despite the high social and economic value of the tuna industry, a considerable amount of tuna catch is lost due to various issues related to meat quality. Some of the meat quality problems known to the tuna industry are decomposition and spoilage associated with high histamine content37,38, burnt or YAKE tuna39,40, jelly meat41,42, honeycomb38,43 and soft tuna syndrome (STM)44.

This study is centered around YAKE. Burnt flesh syndrome, or Yake in Japanese, manifests itself when tuna face stressful situations at slaughter or during fishing. The presence of Yake causes the fish to have metallic flavors and a brownish color, accelerating the degradation process with a decrease in pH. The appearance of Yake means a drop in commercial value and is very punished in certain markets, especially the Japanese market, where tuna meat is largely destined for sashimi preparations that demand the highest level of quality.

The ability of different tuna species to withstand YAKE varies significantly. Species like the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) are notably more vulnerable due to their rapid metabolic rates and the tendency to accrue elevated concentrations of lactic acid in their muscle tissue under stress. These particular tuna, frequently harvested from warm marine environments and exposed to extended storage durations, exhibit increased susceptibility to YAKE.

At this point, the method of distribution and marketing of tuna should be taken into account. Three principal distribution methods can be identified: frozen loins of precooked tuna for the canning industry, fresh tuna loins (essentially for certain culinary tastes such as sushi and sashimi), frozen loins for processing into fillets or for subsequent fresh market.

Notably, the latter method is gaining wider application for the fresh market and is characterized by a whole distribution chain with the loins at very low temperature. This market shows strong growth potential, offering advantages in product preservation and sustainability by eliminating the need for air transport. However, it is clear that the detection of certain anomalies such as those mentioned above with frozen fish is considerably more difficult.

To date, the fishing industry has relied on a visual and not very objective method to measure YAKE in tuna. However, this assessment must be performed after the tuna has thawed. This indicates that the evaluation occurs at the final stage of the distribution chain, making it difficult to address the issue of having acquired tuna that does not meet quality standards.

There are products on the market that use specific enzymatic biosensors that can perform a characterization at the following levels45 in Table 1. In this paper, a two-class classification is adopted in which categories A and B+ would belong to the class (without YAKE) and the rest of the categories (B and C) would be the class (with YAKE).

However, it is necessary to take the samples for the pipettes from the tail part of the loins (even when frozen), and the response times are not less than 2 min (without taking into account the time to extract the samples and place them in the pipettes, which considerably increases the times).

An improvement of the technique for the detection of YAKE in the frozen state through the use of impedance spectroscopy would be very useful in the food industry. In tuna feed chains, the time available for sorting is less than 5 s.

FPGA system architecture

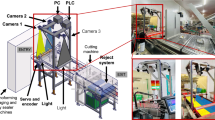

The system implemented on zynq 7020 Redpitaya is presented in Fig. 1. The developed hardware is described in the PL (Programmable Logic) section, which is divided into two large blocks: the acquisition, processing, and generation section, with the module called GAP, and the analysis section that is performed by the module ANN PE and the Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU).

GAP, ANN PE, and GRU are described in more detail in the following sections.

FPGA generation, acquisition and preprocessing GAP

Application latency is a crucial aspect in the assessment of AI at the edge. Within impedance spectroscopy, the sequence-driven nature of input signals influences the entire system, including the AI block, thereby significantly impacting the overall application latency.

Initial implementations, where data collection was controlled either by the cloud host or the embedded host using the instrument’s native applications, were abandoned as the data acquisition time surpassed 10 s. This determined that control of both the generation, acquisition, and subsequent processing was to obtain the moduli and phases of each of the frequencies swept by our spectroscopy, as close as possible to the AD and DA converters. This meant transferring everything to the PL sector of the System-on-a-Programmable Chip (SOPC) used, as shown in Fig. 2.

This project realizes an efficient method for calculating the impedance between two points in a circuit using orthogonal projections on sine and cosine functions. This approach is ideal for implementation in embedded systems such as FPGAs, as it avoids the need to perform Fourier transforms.

If two points are available in the circuit, A and B, with alternating voltages \(V_A(t)\) and \(V_B(t)\), respectively. In addition, the point B is connected to ground through a resistance of shunt, which allows us to determine the current flowing between these points:

The unknown impedance between A and B is indicated by \(Z=R+jX\) and can be calculated using orthogonal projections of the measured signals onto sinusoidal bases.

Orthogonal projections

To extract the amplitude and phase information from the signals, projections are taken onto sine and cosine at the fundamental frequency:

-

For the differential voltage \(V(t)=V_A(t) - V_B(t)\):

-

In-phase projection:

$$\begin{aligned} V_c = \frac{2}{T} \int _{0}^{T} V(t) \cos (\omega t) \, dt \end{aligned}$$(2) -

Quadrature projection:

$$\begin{aligned} V_s = \frac{2}{T} \int _{0}^{T} V(t) \sin (\omega t) \, dt \end{aligned}$$(3)

-

-

For the voltage \(V_B(t)\) (related to the current I(t) ):

-

In-phase projection:

$$\begin{aligned} V_{B_c} = \frac{2}{T} \int _{0}^{T} V_B(t) \cos (\omega t) \, dt \end{aligned}$$(4) -

Quadrature projection:

$$\begin{aligned} V_{B_s} = \frac{2}{T} \int _{0}^{T} V_B(t) \sin (\omega t) \, dt \end{aligned}$$(5)

-

Since \(I(t)= \frac{V_B(t)}{SHUNT}\) , the current projections are as follows:

Impedance calculation

The impedance \(Z=R+jX\) is obtained as follows:

-

Module of impedance:

$$\begin{aligned} |Z| = SHUNT \times \frac{\sqrt{V_c^2 + V_s^2}}{\sqrt{V_{Bc}^2 + V_{Bs}^2}} \end{aligned}$$(7) -

Phase angle:

$$\begin{aligned} \theta = \tan ^{-1}\left( \frac{V_s}{V_c}\right) - \tan ^{-1}\left( \frac{V_{Bs}}{V_{Bc}}\right) \end{aligned}$$(8)

The real and imaginary parts of can be computed as:

FPGA implementation

To efficiently implement this method in hardware:

-

Hardware multipliers are used to compute products such as \(V_Acos(\omega t)\) and \(V_Bcos(\omega t)\) .

-

Accumulators are implemented to approximate the integrals as discrete sums.

-

Division and square root calculations can be performed using the CORDIC algorithm

-

Arc tangent are implemented through lookup tables to improve efficiency.

This approach is hardware-efficient and enables real-time estimations without the need to transform signals into the frequency domain using FFT.

An interesting aspect of this type of application is that the initiation trigger is produced by the application itself. This can occur as a result of a user’s action or through feedback from a pressure sensor, signaling proper contact with the study subject. Ultimately, this results in a start signal that initiates the process of generating and acquiring the ANN inputs.

The number of inputs to the ANN can be calculated by multiplying the number of impedance spectra collected (in this work, this value is set to 1, although it has the potential to reach up to 4 successive iterations) by the number of frequencies in each spectrum (225 in our case, obtained through logarithmic interpolation between 40 Hz and 1 MHz) and then by two, representing the impedance modulus and phase data per frequency. Consequently, the input layer of our neural network, which is designed to classify the object under study, consists of 450 inputs (1 \(\times\) 225 \(\times\) 2). In our acquisition setup, resulting in the last two ANN inputs (impedance modulus and phase at 1 MHz) being ready 1.13 s after the acquisition starts.

ANN processing engine

In light of the topology outlined in the previous section, our component has been designated as the ‘ANN processing engine’ (ANN PE). Figure 3 illustrates the fully integrated ANN PE together with all the necessary components for communication with the microprocessor and DDR memory. The system employs the “Advanced Microcontroller Bus Architecture” (AMBA) protocols to link various system blocks: the AXI-Lite protocol is used for configuring each function, the AXI-Memory Mapped Full protocol (AXI-MM Full) facilitates data transfer between the ANN PE and DDR memory, and AXI-STREAM manages data transfer between the internal functions of the ANN PE.

The ANN PE block has been divided into four blocks designed with High-Level Synthesis (HLS): DMA WRITE, DMA READ, Matrix-Vector Multiplication (MVM), and Activation Function (AF). The DMA READ and DMA WRITE blocks are engineered to execute “Direct Memory Access” (DMA) operations on DDR memory. Specifically, the DMA READ block facilitates data retrieval, while the DMA WRITE block handles data storage. The DMA READ block employs the AXI-MM Full protocol to access DDR memory for raw samples that have been stored by the GRU unit or results of perceptron layers performed in previous phases by this same section and which have also been temporarily stored in the DDR.

The output data from the DMA read function is a stream in fixed-point or floating-point format, depending on the implemented solution.

The MVM block receives read samples and ANN weights via the AXI-MM protocol. Before computations start, the number of neurons to process must configure the MVM block. Upon MVM setup, calculations begin as long as the AXI-STREAM input contains valid data. Once a neuron’s computation finishes, the result is sent using the AXI-STREAM protocol to the AF block, which executes the activation function using a look-up table. Finally, the DMA WRITE block writes the results of the current layer in DDR memory.This process is repeated for each layer using the results of the previous layer as input.

This structure, which has already published its results in46 would allow us to implement any multilayer perceptron (MLP). Unfortunately, despite possessing an internally developed accelerator, and despite having run times that would allow us to meet the necessary latencies to autonomously include the AI classifier from the direct GAP data (about 450 entries), this AI phase does not provide tuna quality classification results worth commenting on.

Consequently, it was necessary to establish a novel preprocessing method bridging GAP and PE-ANN, which can be considered the principal contribution of this study. Its significance for the results will be explained in the subsequent sections.

Recurrent neural networks: LSTM and GRU cells

Principal concept of the primary contribution

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are a type of artificial neural network designed to process sequential data, where the order of the data points is important. Unlike traditional feedforward neural networks, RNNs have a “memory” that allows them to remember past inputs and use that information to influence their current output. This makes them well-suited for analyzing time-series data, such as impedance spectra, where the impedance values at different frequencies are related.

The aim of this work is to evaluate the feasibility of utilizing recurrent neural networks with datasets characterized by frequency sequences along the x-axis rather than temporal sequences. These networks could then be integrated with dense layers typical of MLPs (perfectly implementable with our ANNPE as described in Sect. 2.2). Notable prior implementations have utilized such recurrent networks in the analysis of hyperspectral images47,48. Nevertheless, these investigations do not clearly outline the use of these recurrent networks (LSTM), and they appear to apply them predominantly for spectral time series. This scenario is a constraint for this work, in part because it would hinder rapid inference. In this case, the time series is substituted by a sequence of data derived from impedance measurements at multiple frequencies, which will be collected in a data time series spanning approximately 1 s as per the acquisition and processing setup utilized in this study.

There are several types of RNN, each with its own architecture and characteristics:

-

Standard RNN: The most basic type of RNN, where the output at each time step depends on the current input and the hidden state of the previous time step. These are the original recurrent networks that have been progressively replaced in this listing.

-

Bidirectional RNNs (BRNNs): BRNNs process the input sequence in both directions, forward and backward, allowing them to capture information from past and future time steps.

-

Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs): LSTMs are a type of RNN that can learn long-term dependencies in sequential data. They have a more complex architecture than standard RNNs, with a memory cell that can store information for extended periods.

-

Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs): GRUs are a simpler variant of LSTMs that can also learn long-term dependencies. They have fewer parameters than the LSTMs, making them faster to train.

RNNs work by processing the input sequence one element at a time (frequency), updating their hidden state at each step. The hidden state acts as a memory that stores information about past inputs (frequencies). The output of the RNN at each time step (frequency step) depends on the current input and the hidden state.

Advantages of recurrent networks in processing impedance spectroscopy (IS) data

RNNs offer several advantages for processing IS data:

-

Capturing temporal dependencies: RNNs can capture temporal dependencies in impedance spectra, where the impedance values at different frequencies are related.

-

Handling variable-length sequences: RNNs can handle impedance spectra with different lengths, which is important because the frequency range used in IS can vary depending on the application.

-

Learning complex patterns: RNNs can learn complex patterns in impedance spectra, which can be used to identify different food properties or changes in food quality.

In summary, the combination of models based on RNN networks (mainly LSTM) and spectral profiles has demonstrated its effectiveness in a wide variety of food analysis, such as the prediction of storage time of black tea49, the discrimination of cumin and fennel47, the classification of apples50 the detection of defective eggs51, the classification of citrus fruits52, among others. But it is very important to emphasize that in all these articles the classification systems are based on the acquisition, in several time units, of spectra or images that are processed by convolutional networks in most cases for the extraction of these spectra of certain characteristics, and then go through a recurrent model that analyzes the temporal evolution of these processing chains in order to do the classification. This approach differs fundamentally from those previously reported in the literature.

Among the different types of recurrent networks, GRU cells will be used. This type of network is specifically intended to work with time series, but with computational requirements lighter than those of LSTM. It is important to note that available resources in the PL (see Fig. 1) are limited, and classification latency must be minimized.

GRU cell: recurrent bias after multiplication

The “recurrent-bias-after-multiplication” version of the GRU layer applies the recurrent bias after the multiplication of the previous hidden activation with the recurrent weights. This is the default option used by tensorflow as it allows, in certain experiments, to improve convergence in training and generalization in tasks such as time series processing and language modeling, is more stable numerically avoiding hyperbolic tangent saturation and can improve learning in tasks where short and long term memory control is critical.

Equations

The equations for this version are as follows:

where:

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(x_t\) is the input at the frequency step t.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(h_t\) is the hidden activation at frequency step t.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(z_t\) is the update gate.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(r_t\) is the reset gate.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\({\tilde{h}}_t\) is the candidate hidden activation.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(W_z\), \(W_r\), \(W_h\) are the input weight matrices.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(R_z\), \(R_r\), \(R_h\) are the recurrent weight matrices.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(b_z\), \(b_r\), \(b_h\) are the input biases.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(b_{rz}\), \(b_{rr}\), \(b_{rh}\) are the recurrent biases.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(\tau\) is the hyperbolic tangent function.

- \(\rightarrow\):

-

\(\odot\) represents element-wise multiplication.

The structure of the GRU cell can be seen more clearly in Fig. 4.

Design and verification

Design

The design is done in SystemVerilog. The matrix vector multiplications seen in Fig. 4 are resolved as follows:

-

First, the RESET (\(W_r\)) and UPDATE (\(W_r\) ) gate matrices have been stacked vertically and the input vectors (\(x_t\)) and the hidden neuron activities (\({\tilde{h}}_t\)) have been stacked horizontally.

-

The input biases and the recurrent biases of both gates have been grouped: \(b_z\)+ \(b_{rz}\) , \(b_r+ b_{rr}\).

-

The GRU cell is replicated as many times as candidate hidden activation. That means that matrix vector multiplications will be converted into n vector vector multiplications.

-

For each vector multiplication, a multiplier and an accumulator were used.

-

The sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent functions will be implemented on the basis of tables.

-

The following representation will be used Q8.8 The digital block diagram needed for the specific case of 4 hidden neurons was shown in Fig. 5.

In terms of latency, the operation demands merely 30 clock cycles at a frequency of 125 MHz. Consequently, assuming prior activations are retained, the outputs of the hidden neurons from the final iteration can be accessed in 1.13375 s post the acquisition start. The succeeding fully connected neural network would utilize inputs measuring 4 \(\times\) 225, corresponding to 225 steps and 4 hidden neurons.

Verification

For verification, the implemented and trained tensorflow model was imported from Matlab and converted into a reference model (stateful predict) for a co-simulation performed with the toolbox Verifier with the developed HDL implementation. With this, the adequacy of the proposed quantification can be demonstrated, and additionally the latency of the HDL implementation is obtained, which has had to be artificially added to the golden model to correctly represent the error. The test bench used can be seen in the simulink diagram shown in Fig. 6.

Results

Alternatives evaluated in the recurrent impedance spectroscopy (RIS)

Initially, it is important to acknowledge that a variety of alternatives have been generated:

-

Different sets of inputs: 8 values are available for each frequency (in a range between 40 Hz and 1 MHz) which can be extracted from the module (Z) and phase (\(\phi\)) of the impedance. Real (R) and imaginary (X) parts of impedance, real (\(\epsilon ^{'}\)) and imaginary (\(\epsilon ^{''}\)) parts of permittivity, as well as its modulus (\(Z_{\epsilon }\) and phase (\(\phi _{\epsilon }\)). The training datasets have been evaluated across varying configurations, from utilizing a singular parameter (primarily the impedance phase) to incorporating the entirety of all eight parameters.

-

At all times, it has been taken the frequencies on a logarithmic scale.

-

All sample inputs used in learning and testing are acquired by a laboratory instrument: Agilent 4294A (Precision Impedance Analyzer).

-

All classifications used as targets for our training are carried out using the only method currently available, which is the visual inspection of the unfrozen tuna loins.

-

The approach employs both upward sweeping and upward-downward sweeping solutions.

This final approach is particularly noteworthy due to its unconventional structure.and is also inspired by a type of recurrent network that is widely used nowadays: Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks (BRNNs) are a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) that are specifically designed to process sequential data in both directions. This arises from Standard RNNs, which process sequences unidirectionally, generally moving from the past towards the future. This means that they can only use information from previous elements to make predictions about the current element. For tasks like natural language processing, this can be limiting. Words at the end of a sentence can significantly influence the meaning of earlier words. A traditional RNN, processing the sentence left-to-right, would miss this context.

BRNNs address this limitation by processing the input sequence in two directions: Forward Pass: An RNN layer processes the sequence from the beginning to the end, just like a standard RNN. Backward Pass: Another RNN layer processes the same sequence in reverse, from the end to the beginning. At each time step, the BRNN combines the hidden states from both the forward and backward passes. This gives the network access to information from both the past and the future. By having access to both past and future contexts, the network can achieve a much better understanding of the data.

However, this type of network was not considered sufficiently beneficial to use (this configuration is hereafter referred to as BIGRU) because it prevented us from performing the progressive inference that allowed us to greatly reduce our latency, but It was hypothesized that performing an upward frequency sweep followed by a downward sweep could yield additional information for the model (this option will be designated as UDSGRU).

In terms of the networks used, convolutional networks (squeezenet), multilayer perceptrons, and recurrent networks of the LSTM and GRU types have been used. In the first case, the library of existing convolutional networks has been truncated because of the possibility of having very low classification latencies, and waiting for the available resources was sufficient for this type of network. It is possible that the use of alternative convolutional or deep neural network architectures could yield improved results; however, no further experiments were conducted beyond the capabilities of the current platform or the hardware implementations available from previous projects.

Method used to obtain results

A comprehensive set of 184 samples was analyzed. K-fold cross-validation methodology was implemented, with the experimental settings detailed in Table 2.

The summary of the accuracy values obtained in each of the experiments can be seen in Table 3. Table 4 presents the results of a repeated K-fold cross-validation, providing more comprehensive performance metrics. Additionally, two baseline classifiers—Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP)—are included to enable a basic comparative analysis. For both classifiers, the input features consist of the impedance modulus and phase values obtained at each measured frequency. For both cases we use as input parameters the signals obtained (modulus and phase) for each of the frequencies used.

In the following subsections, the most important aspects of each of the options are shown.

Option 1: UDSGRU

The evaluation begins with the option of upward and downward frequency sweep. This approach results in twice as many elements in the data sequence (300 steps instead of 150); however, the implementation is relatively simple, requiring only a GRU cell configured for two inputs and 16 hidden neurons.

From a results perspective, the 10-fold results of the K-fold cross-validation method are first presented in Table 3. It should be noted that in the worst case 72% precision is obtained and in the best case 94.4% precision.

Among the most noteworthy cases, one was selected in which the sensitivity to YAKE detection reached 100% (Table 5) and another in which the specificity of YAKE detection is 100% (Table 6). In false positive and false negative cells, the class to which the misclassified loins belong is highlighted (see Table 1).

The cumulative confusion matrix can be seen in Table 7.

Option 2: BIGRU

It has been used a bidirectional GRU cell. As mentioned above, the calculation of the bidirectional GRU must start after all the input signals have been obtained.

The results derived from the application of a 10-fold K-fold cross-validation procedure are initially exhibited in Table 3. It should be noted that in the worst case 68.4% precision is obtained and in the best case 94.4% precision.

Among the most noteworthy cases, one was selected in which the sensitivity for YAKE detection reached 90% (Table 8) and another in which the specificity of YAKE detection is 100% (Table 9).

The cumulative confusion matrix can be seen in Table 10.

Option 3: LSTM

The 10 fold results of the application of the K-fold cross-validation method are shown in Table 3.

A scenario in which the detection sensitivity of YAKE is 87.5% (Table 11), and another in which the detection specificity of YAKE is 100% (Table 12) and the cumulative confusion matrix can be seen in Table 13.

This is undoubtedly the most frequently used recurring network today. It would require more resources than the GRU recurrent network, and as can be seen from the results there is no obvious improvement. GRUs have a simpler structure than LSTMs, with fewer parameters to learn. This can make them easier to train and less prone to overfitting, especially when dealing with limited amounts of training data.

Option 4: GRU

The 10 fold results of the application of the K-fold cross-validation method are shown in Table 3.

Choosing a scenario where the detection sensitivity of YAKE is 90% (Table 14), and another where the detection specificity of YAKE is 100% (Table 15) and the cumulative confusion matrix can be seen in Table 16.

Analysis of results

In purely performance terms, all options are fairly equivalent in accuracy. All options show better performance with YAKE specificity than with YAKE sensitivity, so this methodology, while achieving approximately 80% classification accuracy, tends to prioritize specificity over sensitivity, which may align more closely with supplier interests than with consumer protection who pays for a quality product. Only the UDSGRU solution (see Table 7) maintains a more balanced solution.

When using modulus and phase as input, the UDSGRU configuration stands out for its sensitivity to YAKE, while the GRU configuration demonstrates higher specificity.

An attempt was made to use only one input: the phase (Option 5 in Tables 2, 3 and 4). The main reason is due to the difficulty in normalizing the data coming from the module signal. It is possible to obtain results around 75%, although it is true that it is easier to perform data augmentation (through the introduction of Gaussian noise)) to reach around 79 %. However, a tendency to prioritize specificity over sensitivity was observed. This configuration is hereafter referred to as PHUDSGRU.

With respect to noise, it is interesting to talk about the sequence used. The experimental samples consisted of 200 points between 40 Hz and 1 MHz. However, values above 500 Hz were clipped by retaining only the last 150 samples. At low frequencies the modulus and phase-sampled signals have a lot of noise, probably due to pressure differences in the sampled tap with the spike sensor used. The presence of these noisy signals significantly impairs the training performance of the classification models.

Option 5 warrants particular attention in comparison to Option 1. This approach involves performing an upward and downward sweep using distinct frequency subsets: odd-indexed samples from the array are used for the upward sweep, while even-indexed samples are used for the downward sweep. As a result, the overall latency of this configuration is equivalent to that of Options 2, 3, and 4.

The evaluation of the seven models is based on a statistical analysis of their performance across multiple metrics, including Accuracy, Sensitivity (Sensitivity_YAKE), and Specificity (Specificity_YAKE). Data were collected using a k-fold cross-validation methodology, ensuring robust and unbiased performance estimates for each model. Before generating the boxplots, a repeated measures ANOVA was performed to assess whether there were statistically significant differences between the models. The results confirmed significant differences, particularly for SVM, which consistently underperformed compared to the other models. The boxplots in Fig. 7 highlight the distribution of metric values across folds for each model. From this analysis, UDSGRU and GRU consistently demonstrate strong performance, with high medians and compact distributions across all metrics, indicating reliability and stability. BIGRU and PHUDSGRU also perform well but exhibit slightly higher variability, particularly in sensitivity, suggesting occasional inconsistencies. In contrast, SVM shows the lowest performance across all metrics, with significantly lower medians and narrow distributions, indicating consistently poor results. MLP has intermediate performance but suffers from high variability, particularly in sensitivity, which could indicate instability.

For the metrics F1 Score, Precision, Recall, and ROC_AUC, the same k-fold cross-validation methodology was applied, and the results were again visualized using boxplots in Fig. 8 to compare the models. The repeated measures ANOVA also confirmed significant differences, with SVM performing significantly worse than the other models. UDSGRU and GRU emerge as the top-performing models, with high medians and compact distributions across all metrics, confirming their robustness. LSTM and PHUDSGRU show moderate performance but are affected by outliers, particularly in recall and precision, which may indicate occasional poor performance in specific folds. MLP exhibits intermediate results but with high variability, especially in recall, suggesting inconsistent behavior. SVM remains the weakest model, with the lowest medians and narrow distributions across all metrics, confirming its unsuitability for this task. Overall, the analysis highlights UDSGRU and GRU as the most reliable and robust models, while SVM and MLP require significant improvements to be competitive.

Performance evaluation

In AI at the edge applications, system latency and, derivatively, application throughput are often some of the most requested performance metrics.

Energy efficiency is also very important when AI at the edge processing is performed in limited battery capacity embedded devices53. Energy efficiency is often reported as the number of operations per joule; but, in this work, mW/Mps, which means energy per operation, is used.

Table 17 presents the results obtained from the implementation of the complete system depicted in Fig. 1. The table distinguishes between the components developed in SystemVerilog (GAP, GPIO, GRU) and those implemented using High-Level Synthesis (HLS) for the ANN processing engine within the programmable logic (PL) section of the device. In terms of performance, the GRU parameter acquisition latency was measured at 165 clock cycles (1.32 \(\upmu \text {s}\)), calculated from the end of data acquisition for each impedance spectroscopy frequency step. Out of these, 135 cycles are attributed to modulus and phase processing computations, while 30 cycles correspond to the GRU cell operations. Analysis of the results clearly indicates that, to generate a 1 MHz sine wave from a 125 MHz clock source, the minimum necessary period count at each frequency is at least 2, thus amounting to 250 clock cycles.

To show the existing capacity of the ANN processing engine, Table 18 shows the results obtained with the 256 \(\times\) 256 \(\times\) 10 topology, assuming an input of 784 parameters, working in single precision floating point and handling different bus sizes for the connection between the matrix vector multiplication unit and the DDR. In the case of the topology involved in our designs (2400 \(\times\) 320 \(\times\) 32 \(\times\) 2) it would take 6.2 ms to process the MLP part of our deep network.

Conclusions and future directions

AI in edge applications must be low power, portable and low cost, with high performance and low latency. This paper presents a functional impedance spectroscopy system for the industry of food, and specifically for the quality of the tuna. The works demonstrate it is possible to use a low-cost FPGA device to implement a system with data acquisition, generation, and complex ANN-based data analysis blocks.

The combination of impedance spectroscopy followed by a recurrent neural network proves to be an original solution that has not been used before and that gives good results. A series of data obtained at different frequencies is treated as a time series. Indeed, data series are acquired at different instants in time; but the characteristics of the sensed signal are different because sine signals at different frequencies are used.

It is possible to observe that the AI procedure used gives good results; it must be transferred to the portable equipment in its entirety. This implies obtaining new learning samples (in a larger number than the one obtained so far), but using the same sensor that is going to be used later in the inference. The differences in procedures, quantifications, signal adaptations, probes, etc. between the equipment used in the laboratory (Agilent 429A) and the equipment presented in Fig. 1 force this procedure to maintain the efficiency of the system.

Regarding the inference time in the classification process, it is evident that the laboratory equipment that performs impedance spectroscopy, with a sweep of 200 points between 40 Hz and 1 MHz, spends more than 10 s only to obtain the module and phase of the impedance. The industry requests dedication times to each tuna loin of less than 5 s (this would include the sensor fixation system, drive, impedance measurement, and AI processing explained in this article). Using the system shown in Fig. 1, times of less than 1.8 s have been achieved for impedance measurement and AI processing. Therefore, it gives a margin for the sensing system and allows us to double the number of measurement points, which would result in improving the accuracy of the classifiers.

There remains the unresolved problem of the noise obtained between 40 and 500 Hz. This may require special designs of the retractable sensor tips to work properly at low temperatures and an adequate mechanical system to guarantee a uniform measurement pressure. In this range, impedance measurements are highly sensitive to the state of cellular structures; intact membranes present higher impedance, while damage, spoilage, or ripening processes that compromise membrane permeability lead to a decrease. This makes the low-frequency spectrum invaluable for evaluating food freshness, tissue damage, and structural changes related to quality.

Future directions involve adapting novel AI algorithms. Especially in the IA following the recursive network used. Although multilayer perceptrons have been favored for implementation efficiency, exploring alternative algorithms may enhance performance.

To accelerate system evolution, the acquisition and generation systems will be migrated to HLS. Furthermore, to improve the accuracy of the system, the option of generating components in HLS with different data types, such as fp16, will be included.

Additionally, the project can be transferred to a more resource-rich FPGA, allowing parallel processing of various ANN implementations. This shift would enhance data analysis capabilities, although it would lead to an increase in system costs.

Data availability

Data is contained within the article.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Materials availability

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

Islam, M., Wahid, K. & Dinh, A. Assessment of ripening degree of avocado by electrical impedance spectroscopy and support vector machine. J. Food Qual. 2018(1), 4706147 (2018).

Ochandio Fernández, A., Olguín Pinatti, C. A., Masot Peris, R. & Laguarda-Miró, N. Freeze-damage detection in lemons using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Sensors 19(18), 4051 (2019).

Matsumoto, S., Sugino, N., Watanabe, T. & Kitazawa, H. Bioelectrochemical impedance analysis and the correlation with mechanical properties for evaluating bruise tolerance differences to drop shock in strawberry cultivars. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 248(3), 807–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00217-021-03928-2/TABLES/2 (2022).

Traffano-Schiffo, M. V., Castro-Giraldez, M., Colom, R. J. & Fito, P. J. Development of a spectrophotometric system to detect white striping physiopathy in whole chicken carcasses. Sensors 17(5), 1024 (2017).

Rizo, A. et al. Development of a new salmon salting-smoking method and process monitoring by impedance spectroscopy. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 51, 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LWT.2012.09.025 (2013).

Sun, J., Zhang, R., Zhang, Y., Li, G. & Liang, Q. Estimating freshness of carp based on EIS morphological characteristic. J. Food Eng. 193, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFOODENG.2016.08.007 (2017).

Sun, J. et al. Classifying fish freshness according to the relationship between EIS parameters and spoilage stages. J. Food Eng. 219, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFOODENG.2017.09.011 (2018).

Pérez-Esteve, E. et al. Use of impedance spectroscopy for predicting freshness of sea bream (Sparus aurata). Food Control 35(1), 360–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODCONT.2013.07.025 (2014).

Sun, J. et al. A fusion parameter method for classifying freshness of fish based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Food Qual. 2021, 6664291. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6664291 (2021).

Niu, J. & Lee, J. Y. A new approach for the determination of fish freshness by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Food Sci. 65, 780–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2621.2000.TB13586.X (2000).

Zhao, X. et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy for quality assessment of meat and fish: A review on basic principles, measurement methods, and recent advances. J. Food Q. 2017, 6370739. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6370739 (2017).

Traffano-Schiffo, M. V., Castro-Giraldez, M., Herrero, V., Colom, R. J. & Fito, P. J. Development of a non-destructive detection system of deep pectoral myopathy in poultry by dielectric spectroscopy. J. Food Eng. 237, 137–145 (2018).

Tönißen, K. et al. Impact of spawning season on fillet quality of wild pikeperch (Sander lucioperca). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 248(5), 1277–1285. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00217-022-03963-7/TABLES/2 (2022).

Zhu, H. et al. Application of machine learning algorithms in quality assurance of fermentation process of black tea- based on electrical properties. J. Food Eng. 263, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFOODENG.2019.06.009 (2019).

Durante, G., Becari, W., Lima, F. A. S. & Peres, H. E. M. Electrical impedance sensor for real-time detection of bovine milk adulteration. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2015.2494624 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Multi-frequency simultaneous measurement of bioimpedance spectroscopy based on a low crest factor multisine excitation. Physiol. Meas. 36(3), 489 (2015).

Ruiz-Vargas, A., Arkwright, J., & Ivorra, A. A portable bioimpedance measurement system based on red pitaya for monitoring and detecting abnormalities in the gastrointestinal tract. In 2016 IEEE EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES), 150–154 (2016). IEEE.

Retzler, A. et al. Improved crest factor minimization of multisine excitation signals using nonlinear optimization. Automatica 146, 110654. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AUTOMATICA.2022.110654 (2022).

Ojarand, J., Rist, M., & Min, M. Comparison of excitation signals and methods for a wideband bioimpedance measurement. In Conference Record—IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference 2016-July (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/I2MTC.2016.7520555

Sanchez, B., Louarroudi, E., Bragos, R. & Pintelon, R. Harmonic impedance spectra identification from time-varying bioimpedance: Theory and validation. Physiol. Meas. 34, 1217. https://doi.org/10.1088/0967-3334/34/10/1217 (2013).

Shi, W. & Dustdar, S. The promise of edge computing. Computer 49, 78–81. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2016.145 (2016).

Pekar, A., Mocnej, J., Seah, W. K. G. & Zolotova, I. Application domain-based overview of IoT network traffic characteristics. ACM Comput. Surv. https://doi.org/10.1145/3399669 (2020).

What is Edge AI and How Does It Work?—NVIDIA Blog. https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/what-is-edge-ai/

Son, D., Lee, S., Jeon, S., Kim, J. J. & Chung, S. Classifying storage temperature for mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.) using bioimpedance and diameter measurements with machine learning. Sensors 25, 2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/S25082627/S1 (2025).

McDermott, C., Lovett, S. & Rossa, C. Improved bioimpedance spectroscopy tissue classification through data augmentation from generative adversarial networks. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 62, 1177–1189. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11517-023-03006-7/TABLES/2 (2024).

Hamed, S., Altana, A., Lugli, P., Petti, L. & Ibba, P. Supervised classification and circuit parameter analysis of electrical bioimpedance spectroscopy data of water stress in tomato plants. Comput. Electron. Agric. 226, 109347. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2024.109347 (2024).

Qiu, J. et al. Rapid beef quality detection using spectra pre-processing methods in electrical impedance spectroscopy and machine learning. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 59, 1624–1634. https://doi.org/10.1111/IJFS.16915;CTYPE:STRING:JOURNAL (2024).

Li, H. et al. Performance of an implantable impedance spectroscopy monitor using Zigbee. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 224, 012163. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/224/1/012163 (2010).

Hoja, J. & Lentka, G. Interface circuit for impedance sensors using two specialized single-chip microsystems. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 163, 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SNA.2010.08.002 (2010).

Ibba, P. et al. Design and validation of a portable ad5933-based impedance analyzer for smart agriculture. IEEE Access 9, 63656–63675. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3074269 (2021).

Jenkins, D. M., Lee, B. E., Jun, S., Reyes-De-Corcuera, J. & McLamore, E. S. Abe-stat, a fully open-source and versatile wireless potentiostat project including electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, 3056–3065. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0061909JES/XML (2019).

Istanbullu, M. & Avci, M. An ANN-based single calibration impedance measurement system for skin impedance range. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 3776–3783. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2020.3022483 (2021).

Jiang, Z. et al. Development of a portable electrochemical impedance spectroscopy system for bio-detection. IEEE Sens. J. 19(15), 5979–5987 (2019).

Tsukahara, A., Yamaguchi, T., Tanaka, Y. & Ueno, A. FPGA-based processor for continual capacitive-coupling impedance spectroscopy and circuit parameter estimation. Sensors 22, 4406. https://doi.org/10.3390/S22124406 (2022).

Watson, C. Chapter 7 burnt tuna: A problem of heat inside and out? In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Fishes (vol. 5, 127–145, 1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1873-0140(06)80033-0

Kruijssen, F. et al. Loss and waste in fish value chains: A review of the evidence from low and middle-income countries. Global Food Secur. 26, 100434. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GFS.2020.100434 (2020).

Debeer, J. et al. Processing tuna, scombridae, for canning: A review. Mar. Fish. Rev. 83, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.7755/MFR.83.3-4.1 (2021).

Frank, H.A., & Yoshinaga, D.H. Histamine formation in tuna, 443–451 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1021/BK-1984-0262.CH037

Erdaide, O., Lekube, X., Olsen, R. L., Ganzedo, U. & Martinez, I. Comparative study of muscle proteins in relation to the development of Vake in three tropical tuna species yellowfin (Thunnus albacares), big eye (Thunnus obesus) and skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis). Food Chem. 201, 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.059 (2016).

Ikehara, W., Cramer, J.L., Nakamura, R.M., Dizon, A.E., & Ikehara, W.N. Burnt Tuna: Conditions Leading to Rapid Deterioration in the Quality of Raw Tuna.

Bolin, J. A. et al. First report of Kudoa thunni and Kudoa musculoliquefaciens affecting the quality of commercially harvested yellowfin tuna and broadbill swordfish in eastern Australia. Parasitol. Res. 120, 2493–2503. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00436-021-07206-8/FIGURES/3 (2021).

Henning, S. S., Hoffman, L. C. & Manley, M. A review of Kudoa-induced myoliquefaction of marine fish species in South Africa and other countries. S. Afr. J. Sci. 109, 5–5. https://doi.org/10.1590/SAJS.2013/20120003 (2013).

Frank, H.A., Rosenfeld, M.E., Yoshinaga, D.H., & Nip, W.-K. Relationship Between Honeycombing and Collagen Breakdown in Skipjack Tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis.

Stagg, N. J., Amato, P. M., Giesbrecht, F. & Lanier, T. C. Autolytic degradation of skipjack tuna during heating as affected by initial quality and processing conditions. J. Food Sci. 77, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1750-3841.2011.02543.X (2012).

BIOFISH 3000 YAKE - Biolan. https://biolanmb.com/biofish-3000-yake/

Fe, J. et al. Improving FPGA based impedance spectroscopy measurement equipment by means of HLS described neural networks to apply edge AI. Electronics 11, 2064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ELECTRONICS11132064 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Fast detection of cumin and fennel using NIR spectroscopy combined with deep learning algorithms. Optik 242, 167080. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJLEO.2021.167080 (2021).

Pang, L. et al. Feasibility study on identifying seed viability of Sophora japonica with optimized deep neural network and hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 190, 106426. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2021.106426 (2021).

Hong, Z., Zhang, C., Kong, D., Qi, Z. & He, Y. Identification of storage years of black tea using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging with deep learning methods. Infrared Phys. Technol. 114, 103666. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INFRARED.2021.103666 (2021).

Shi, X., Chai, X., Yang, C., Xia, X. & Sun, T. Vision-based apple quality grading with multi-view spatial network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 195, 106793. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2022.106793 (2022).

Turkoglu, M. Defective egg detection based on deep features and bidirectional long-short-term-memory. Comput. Electron. Agric. 185, 106152. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2021.106152 (2021).

Yu, Y., An, X., Lin, J., Li, S. & Chen, Y. A vision system based on CNN-LSTM for robotic citrus sorting. Inf. Process. Agric. 11, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INPA.2022.06.002 (2024).

Sze, V., Chen, Y.-H., Yang, T.-J. & Emer, J. S. How to evaluate deep neural network processors: Tops/w (alone) considered harmful. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Mag. 12(3), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSSC.2020.3002140 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by grant PID2020-116816RB-100 from Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU) of Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.; Methodology, R.G.-G. and J.F.; Validation, P.J.F and M.C.-G.; Investigation, R.G.-G. and J.M.M.; Resources, R.C.-P.; Writing—original draft, R.G.-G.; Writing—review and editing, P.J.F and J.M.M.; Supervision, R.C.-P. and M.C.-G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gadea-Girones, R., Monzo, J.M., Colom-Palero, R. et al. A FPGA based recurrent neural networks-based impedance spectroscopy system for detection of YAKE in tuna. Sci Rep 15, 22046 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05728-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05728-0