Abstract

Benzodiazepines are commonly identified in drug overdose deaths worldwide. However, research on their effects on the most common necrophagous insect species is limited. In this context, the current study investigated the effects of clonazepam and flunitrazepam on the development cycle of Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Three blow fly colonies were reared under controlled laboratory conditions (24℃, 50% humidity, 12:12 light-dark cycle), and the experiment was carried out in triplicate. A solution of 4 mg of clonazepam and 2 mg of flunitrazepam, each dissolved in 50 mL of ultrapure water, was added to minced beef liver. The development cycle and growth rate were monitored daily, with a total of 2700 specimens weighed, covering each developmental stage except for the egg clusters. Statistical analyses using aligned rank transform (ART) ANOVA revealed significant interactions between the drug and developmental stages. Larvae exposed to benzodiazepines had higher median weights compared to controls, with more pronounced effects observed during the transition from the third instar larvae to the pupae stage. However, no differences were observed regarding the development cycle length between the three colonies. The findings suggest that clonazepam and flunitrazepam influence C. vicina morphology, particularly weight, which, when size is considered, has potential implications for forensic entomology in estimating the minimum postmortem interval (minPMI).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benzodiazepines are widely used to treat symptoms of anxiety and sleep disorders. Misuse is frequently reported, sometimes being associated with multi-drug overdoses, being involved in suicides, sexual assaults, and crime cases1,2,3with approximately 10,964 recorded deaths in 20223. Recent data on benzodiazepines deaths4 showed that between 2019 and 2020 there was a 20% increase in emergency visits due to benzodiazepines overdose. This percentage included singular and multi-drug cases, the latter being a combination with opioids, like fentanyl. Overdose related deaths increased by 42.9% for the same time span, from 1,004 to 1,435 deaths4. The same report with data generated from 23 states showed that benzodiazepines were involved in 6,982 of the 41,496 overdose reported deaths, while opioids were identified in 6,384 of the cases. In the first half of 2020, there were 2,721 overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines, with 2,174 linked to prescription benzodiazepines and 532 to illicit benzodiazepines4. The most affected age group was the 25–34 years old category for overdose emergency visits, while the 45–64 years old group was the most affected category of benzodiazepine-involved deaths4.

In ante-mortem biological samples, benzodiazepines can be detected up to 10 days from urine5 2.5 days from oral fluids6 24 h from blood7 and up to 90 days from hair samples8. Once ingested, the effects of the drug will depend on the specific benzodiazepine, its concentration, the individual’s general health, and the use of other substances9. Moreover, the ingested substance will be metabolized primarily in the liver, breaking down into various metabolites10. If the ingested dose exceeds toxic levels, it can result in death of the individual11. Since the early 2000 s, benzodiazepines and their metabolites are often reported in postmortem specimens12. Compared to samples collected from living individuals, postmortem toxicological samples pose several challenges13,14,15 including the risk of decomposition, which can lead to changes in the chemical composition of the samples, and the redistribution of substances within the body after death16,17. Furthermore, postmortem samples may be influenced by factors such as environmental conditions and the presence of other substances that can complicate accurate analysis. Higher temperatures were found to be responsible of a faster degradation of ketazolam and chlordiazepoxide, while lorazepam and estazolam remained relatively stable when stored at −20 °C and − 80 °C15. Moreover, the biotransformation of parent drugs to metabolites can continue during the storage of the postmortem samples14. After death, during the fresh stage of decomposition or upon body discovery, biological tissues and fluids will be sampled for toxicological analyses during the autopsy18. If a body is found in an advanced stage of decomposition, identifying benzodiazepines from decomposed samples can be challenging. In such cases, when present, necrophagous insect species collected from the body can serve as an alternative sample type for drug detection1.

The development of forensic entomotoxicology expanded decades ago19 focusing primarily on the detection of drugs from different insect species20,21,22. Necrophagous insect species, mainly calliphorids, were used for these investigations, as these are typically the first insects to arrive and colonize a body minutes to hours after death23,24. Their presence and activity is influenced by a number of factors, starting with the environmental temperature, geographical location, manner of death, up to the presence of different drugs in the feeding substrate, represented by decomposed organic matter24. Different analytical methods, such as liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) were tested to detect benzodiazepines from different Calliphoridae species, including Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 18301. Other studies25 focused on developing non-destructive methods for flunitrazepam identification from various developmental stages of Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) (Diptera: Calliphoridae), or used Fourier-transformed infrared (FTIR) microscopy26 as well as other identification procedures to identify benzodiazepines from insect tissues27,28,29,30,31. Several benzodiazepines could be detected from insect samples, including flunitrazepam, clonazepam1 diazepam22 and nordiazepam32.

The necrophagous insect species developmental stages, and arthropod community succession are analyzed for the estimation of the minimum postmortem interval (minPMI)24. Since this estimation is often based on the developmental stages, and knowing that the rate of development can be influenced by different factors including various drugs and toxins, several studies focused on understanding the influence of different drugs on the growth rate of various Calliphoridae species33,34,35. To better understand the growth rates as they relate to time, several studies36,37,38,39 have investigated the development of calliphorids, including C. vicina. This species is oviparous and can lay up to 300 eggs in a cluster, primarily in body orifices (e.g. mouth, nose) and open wounds23. The larvae hatch approximately 24 h later, feeding and growing for several days through the first, second, and third instars40. Towards the end of the third larvae stage, the specimens cease feeding and migrate away from the food source (e.g. animal carcass, human body) to pupate. During the pupal stage, which lasts for several days, the larval tissues undergo metamorphosis, culminating in the emergence of teneral specimens (newly hatched adults)23. Knowing that the life cycle dynamics is species-specific and primarily temperature dependent, these studies monitored the growth rates at different temperatures to better understand the developmental stages’ temperature dependency, including changes in larvae length and survival rates36,41. This approach aims to achieve more accurate reference data for the minPMI estimation, recognizing that temperature-dependent growth rates vary significantly among different insect species. Reference rearing data is commonly used in forensic cases involving insect evidence42 taking into account the macro and micro environment of each crime scene, including the presence of drugs in the decomposed tissues.

Overall, research focused on the effects of benzodiazepines on blowfly species development are scarce. In this context the current study aimed to answer the following questions: (1) Are flunitrazepam and clonazepam causing changes in the growth rate of C. vicina, a primary Calliphoridae colonizer? (2) Are there any differences in the overall development cycle times between the three treatments (control, clonazepam, and flunitrazepam)?

Results

Benzodiazepines influence on C. vicina development cycle

There were no notable differences observed in the time length of the development cycle between the two colonies fed with inoculated liver and the control colony (Fig. 1, Table S1). All specimens took approximately 546 h to reach the teneral stage from the moment of oviposition (Table S1). The time differences in Table 1 account for the variations in weighing times for each colony.

Benzodiazepines effect on C. vicina weight

The ART ANOVA test revealed significant interactions between the substance used on the feeding substrate and developmental stage, related to the weight of the larvae (F (8, 28.628) = 8.2309, p < 0.0001). The median weight of the larvae was significantly higher in the colonies exposed to benzodiazepines compared to those with no treatment (clonazepam: t = −6.164, df = 28.1, p < 0.0001, flunitrazepam: t = −5.018, df = 28.1, p = 0.0001). However, there was no significant difference in the median weight of larvae from colonies where flunitrazepam and clonazepam were present (t = 1.278, df = 28.4, p = 0.4191). The pairwise test of differences in pairwise combinations of levels between factors in interactions did not reveal significant differences in median weight from control colonies compared to colonies exposed to benzodiazepines when larvae developed from the first instar larvae (L1) to the second instar larvae (L2), but differences appeared later in development, as the median weight was significantly different between control and benzodiazepine specimens moving from the third instar larvae (L3) to the pupae stage (Table S1, Fig. 2). Overall, differences were more pronounced for flunitrazepam, as the median weight was significantly different for the larvae exposed to this substance compared to control in almost all developmental stages, except for the first and second instar larvae (Fig. 2). The differences were statistically significant for clonazepam compared to control only when transitioning from the third instar larvae to the pupae stage (Table S2, Fig. 2). Although the median weight was higher for the larvae grown on flunitrazepam inoculated liver, differences between the two benzodiazepines were only significant moving from pupae to teneral stage (Table S1, Fig. 3).

Interaction plot showing the mean weight (in mg) of Calliphora vicina at various developmental stages (L1 = first instar larvae; L2 = second instar larvae; L3 = third instar larvae; P = pupae; T = teneral) under different feeding conditions: control (red); clonazepam (green); flunitrazepam (blue). The mean weight of the third instar larvae and pupae is higher in the benzodiazepine-exposed groups compared to the control group.

There was no evidence of association between the feeding substrates and the frequency of hatched males and females (χ2 = 0.12585, df = 2, p = 0.939).

Discussion

Whether used therapeutically or obtained illegally, benzodiazepines can negatively impact the overall health of an individual, potentially leading to life-threatening conditions and, in some cases, death4,43. The pharmacokinetics and postmortem distribution of each drug in this class vary and understanding how these factors affect different necrophagous insect species could provide valuable reference data for when estimating the minPMI.

Differences in the weight of fly specimens collected from decomposed remains can influence the estimates of the minPMI, as heavier larvae typically indicate more advanced development44. In the current experiment, both benzodiazepines influenced the weight of the specimens exposed to the feeding environment spiked with these drugs. This response may be due to the nervous system malfunction. In the early 198745 researchers used nerve cells from the thoracic ganglia of two locust species to test the Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the insect nervous system, and muscimol, to examine how they respond to specific voltages. They found that, as a reaction, the cells become more negatively charged, while the presence of flunitrazepam enhanced the rapid response without extending the duration of the cellular reaction. As demonstrated45,46 insect GABA receptors have sites that can be modulated by benzodiazepines, such as flunitrazepam and clonazepam.

Benzodiazepines can enhance the effects of GABA, increasing the opening of chloride channels, leading to a grater inhibition of the neuronal activity47. This, in turn, decreases signal transmission between neurons, modulating behavior and physiology. Nevertheless, in this earlier study45 flunitrazepam did not appear to affect the resting state of the cells or their basic electrical properties. The results suggested that the flunitrazepam effect is not due to blocking GABA uptake but rather to its direct action on the GABA receptors. The overall activity of the neurons is reduced, leading to a potential calming effect48. Although GABA is widespread among vertebrate and invertebrate species49 previous studies have shown that the benzodiazepines binding sites for insect GABA receptors are pharmacologically different than in vertebrate species50. A study on Periplaneta americana (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera: Blattidae)46 confirmed once again that there is a clear pharmacological difference between the insect and mammalian native GABA-gated chloride channels when considering the benzodiazepines effects. These neuronal modifications could explain the changes in body mass, as it has been demonstrated that flunitrazepam can bind to the insect neuronal tissue51.

The cause of larvae and pupae weight gain could be explained by the disruption of normal neuronal activities. A previous study52 investigating the associated effect of ethanol and flunitrazepam showed that only the 7-aminoflunitrazepam impacted the growth rate, causing longer lengths of the larvae stages. Another study53 focused on the effect of flunitrazepam on C. megacephala species growth rates revealed that the drug impacted the weight gain of the pupae and adults. These findings are supported by the current results, especially for the pupa stage, where the median weight of the specimens exposed to benzodiazepines was significantly higher than the control specimens. Noteworthy, there were no significant differences between the two drugs regarding the growth rate. Moreover, Baia and collaborators53 used different flunitrazepam concentrations and found that the pupae were heavier when using a higher concentration in the feeding environment. The development cycle of several calliphorid species has been affected by the presence of carbamazepine and clobazam in the feeding substrate54. Clonazepam studies are scarce, with only a few investigating the effects on a sarcophagid species55 and a phorid species56. Clonazepam was found to have an impact on the increase in weight of the third larval stage55 and on the acceleration of the development cycle56.

Carvalho and collaborators22 found that diazepam can have an influence on the minPMI estimation when present in the feeding substrate of Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) and Chrysomya putoria (Wiedemann, 1830), as it alters the growth of these two calliphorid species. Other substances, such as cocaine57 methamphetamine58 and ketamine33 can accelerate the development cycle of necrophagous insects. Results should be interpreted with caution, as the same substance, such as ketamine, can either accelerate the development33 or have no correlation59 when tested on two different calliphorid species. The presence of different toxins can have a reverse effect as well, causing delays of the development cycle60,61. When tested on C. megacephala, chemotherapeutic drugs were found to influence the survival rates and sex ratios62. A recent study63 investigated the effect of antibiotics, like ceftriaxone and levofloxacin, on Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758) growth cycle and determined that the larval development and pupation were influenced in different ways.

The length of the development cycle remained unaffected, providing similar findings as previously reported53. Nevertheless, each drug can have a different impact on the life cycle length of various necrophagous insect species64,65. In the current experiment the development cycle had a mean duration of 546 h for all three colonies. When comparing development times for the same species, temperature and relative humidity, even in a controlled insect rearing chamber, must be considered when analyzing the development cycle length.

When drugs are present in the feeding substrate at the concentrations reported in this study and considering that they did not influence the duration of the development cycle, it can be concluded that their impact on the minPMI estimation could be minimal. However, caution should be exercised when analyzing different life stages regarding weight and length changes, as these drugs affected the weight rates in later developmental stages, which can introduce errors in the results interpretation.

Materials and methods

Rearing conditions

The experiment received approval from the Institutional Biosafety Committee, University of North Dakota (IBC-202212-006), complying with the safety and standards protocols.

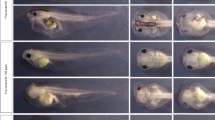

C. vicina third instar larvae were acquired from a local live bait shop. Following emergence, three colonies of 300 C. vicina adults each were reared under constant laboratory conditions (24℃, 50% humidity, 12:12 light-dark cycle) using an insect rearing chamber (Caron, USA) (Fig. 4A). The adults were provided daily with water and honey, while 200 g of minced beef liver was placed in each rearing cage until oviposition occurred five days later (Fig. 4B). Several larvae and adult specimens were taxonomically identified under a Leica S9 D stereomicroscope (Leica, USA) for species confirmation, according to the taxonomic identification keys for the blowflies of North America40.

The concentrations of both drugs were based on the toxic dose per kilogram of body weight66,67. Specifically, 4 mg of clonazepam and 2 mg of flunitrazepam were each mixed with 50 mL of ultrapure water using a magnetic stirrer (Thermo Scientific, USA), resulting in concentrations of 0.08 mg/mL for clonazepam, and 0.04 mg/mL for flunitrazepam. The concentrations were not further diluted beyond the initial preparation. The solutions were then spiked into the minced beef liver and manually homogenized, ensuring that no excess liquid escaped from the feeding substrate container.

After oviposition, the egg clusters were transferred to nine rearing containers: three containing minced livers spiked with clonazepam, three containing minced livers spiked with flunitrazepam, and three rearing containers with only minced liver used as control. Each rearing container included 200 g of minced beef. Three egg clusters, each counting approximately 250 eggs, were transferred to each container. The transfer of the egg clusters was randomized to ensure that the same number of clusters were placed in each container. All nine containers were maintained under the same rearing conditions as the adult colonies.

Development cycle monitoring took place daily (every 6 h). Fifty insect specimens, representing adults, first instar larvae, second instar larvae, third instar larvae (mid-stage), pupae, and teneral stages, were weight from each rearing container, totaling 2700 measurements, using an analytical balance (Ohaus Pioneer, USA). During each measurement, the specimens were randomly selected and placed in a second container, until the end of the weighing process, to avoid measuring the same specimen twice (Fig. 2C). The non-destructive approach was used to allow accounting for pupariation and mortality rates, and final adults emergence rates (Fig. 2D). Weighing 450 specimens across all containers for each developmental stage took approximately 4 h. This information was included in the developmental timetable to account for the time differences between measurements. Specimens were monitored daily for developmental stage confirmation, based on the morphological features specific to each stage, especially the larvae stages that were accounted for, based on the number of posterior respiratory slits (spiracles).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the R software environment68. Aligned Rank Transform (ART) ANOVA, implemented in the package ARTool69,70, was used to analyze the effect of benzodiazepines on the weight of C. vicina specimens through the developmental stages (first instar larvae, second instar larvae, third instar larvae, pupae, and teneral); an unique ID composed of the developmental stage and container (e.g. L1 CT1 – stage 1 control container 1) was used as a random factor to account for the potential variability between the three replicates. Pairwise tests to evaluate the influence of each drug at different developmental stages were also conducted using the art.con function71 from the same package. The independence of the resulting sex of individuals from the colonies exposed to the drugs was analyzed using the χ2 test of independence. All analyses were performed at a confidence level of 95%. Plots were produced using the package ggpubr72.

Data availability

All data presented in this study are included within the current manuscript and the supplemental material.

References

Wood, M. et al. Development of a rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of benzodiazepines in Calliphora vicina larvae and puparia by LC-MS-MS. J. Anal. Toxicol. 27, 505–512 (2003).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. UNODC World Drug Report 2024: Harms of World Drug Problem Continue to Mount Amid Expansions in Drug Use and Markets. (2024).

National Center for Health Statistics. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2022. (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db491.pdf

Liu, S., O’Donnell, J., Gladden, M., McGlone, R., Chowdhury, F. & L. & Trends in nonfatal and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines—38 States and the district of columbia, 2019–2020. Am. J. Transplant. 21, 3794–3800 (2021).

Rasanen, I., Neuvonen, M., Ojanperä, I. & Vuori, E. Benzodiazepine findings in blood and urine by gas chromatography and immunoassay. Forensic Sci. Int. 112, 191–200 (2000).

Nordal, K., Øiestad, E. L., Enger, A., Christophersen, A. S. & Vindenes, V. Detection times of diazepam, clonazepam, and Alprazolam in oral fluid collected from patients admitted to detoxification, after high and repeated drug intake. Ther. Drug Monit. 37, 451–460 (2015).

Manchester, K. R., Lomas, E. C., Waters, L., Dempsey, F. C. & Maskell, P. D. The emergence of new psychoactive substance (NPS) benzodiazepines: A review. Drug. Test. Anal. 10, 37–53 (2018).

Usman, M. et al. Forensic toxicological analysis of hair: a review. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 9, 17 (2019).

Dubovsky, S. L. & Marshall, D. Benzodiazepines remain important therapeutic options in psychiatric practice. Psychother. Psychosom. 91, 307–334 (2022).

Hooper, W. D., Watt, J. A., Mckinnon, G. E. & Reelly, P. E. B. Metabolism of diazepam and related benzodiazepines by human liver microsomes. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 17, 51–59 (1992).

Patorno, E., Glynn, R. J., Levin, R., Lee, M. P. & Huybrechts, K. F. Benzodiazepines and risk of all cause mortality in adults: cohort study. BMJ j2941 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2941

Drummer, O. H. & Gerostamoulos, J. Postmortem drug analysis: analytical and toxicological aspects. Ther. Drug Monit. 24, 199–209 (2002).

Byard, R. W. & Butzbach, D. M. Issues in the interpretation of postmortem toxicology. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 8, 205–207 (2012).

Dixon, R. B., Mbeunkui, F. & Wiegel, J. V. Stability study of opioids and benzodiazepines in urine samples by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 6, 17 (2015).

Melo, P., Bastos, M. L. & Teixeira, H. M. Benzodiazepine stability in postmortem samples stored at different temperatures. J. Anal. Toxicol. 36, 52–60 (2012).

Abdelaal, G. M. M., Hegazy, N. I., Etewa, R. L. & Elmesallamy, G. E. A. Postmortem redistribution of drugs: a literature review. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-023-00709-z (2023).

Menéndez-Quintanal, L. M. et al. The state of the Art in Post-Mortem redistribution and stability of new psychoactive substances in fatal cases: A review of the literature. Psychoactives 3, 525–610 (2024).

Stojak, J. Use of entomotoxicology in estimating post-mortem interval and determining cause of death. Issues Forensic Science 295(1), 56–63 (2017).

Beyer, J. C., Enos, W. F. & Stajić, M. Drug identification through analysis of maggots. J. Forensic Sci. 25, 411–412 (1980).

Goff, M. L. & Lord, W. D. Entomotoxicology. A new area for forensic investigation. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 15, 51–57 (1994).

Kintz, P. et al. Fly larvae: a new toxicological method of investigation in forensic medicine. J. Forensic Sci. 35, 204–207 (1990).

Carvalho, L. M. L., Linhares, A. X. & Trigo, J. R. Determination of drug levels and the effect of diazepam on the growth of necrophagous flies of forensic importance in southeastern Brazil. Forensic Sci. Int. 120, 140–144 (2001).

Haskell, N. H. & Williams, R. E. Entomology & Death: A Procedural Guide (East Park Printing, 2008).

Smith, K. G. A Manual of Forensic Entomology (Trustees of the British Museum, 1986).

Oliveira, J. S., Baia, T. C., Gama, R. A. & Lima, K. M. G. Development of a novel non-destructive method based on spectral fingerprint for determination of abused drug in insects: an alternative entomotoxicology approach. Microchem. J. 115, 39–46 (2014).

Baia, T. C., Gama, R. A., Silva De Lima, L. A. & Lima, K. M. G. FTIR microspectroscopy coupled with variable selection methods for the identification of flunitrazepam in necrophagous flies. Anal. Methods. 8, 968–972 (2016).

Campobasso, C. P., Gherardi, M., Caligara, M., Sironi, L. & Introna, F. Drug analysis in blowfly larvae and in human tissues: a comparative study. Int J. Legal Med 118(4), 210–214 (2004).

Manhoff, D. T. et al. Cocaine in decomposed human remains. J. Forensic Sci. 36, 13196J (1991).

Sadler, D. W., Chuter, G., Seneveratne, C. & Pounder, D. J. Barbiturates and analgesics in Calliphora vicina larvae. J. Forensic Sci. 42, 1214–1215 (1997).

Magni, P. A., Pacini, T., Pazzi, M., Vincenti, M. & Dadour, I. R. Development of a GC–MS method for methamphetamine detection in Calliphora vomitoria L. (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Forensic Sci. Int. 241, 96–101 (2014).

Magni, P. A., Pazzi, M., Vincenti, M., Converso, V. & Dadour, I. R. Development and validation of a method for the detection of α- and β-Endosulfan (Organochlorine Insecticide) in Calliphora vomitoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Med. Entomol. 55, 51–58 (2018).

Pien, K. et al. Toxicological data and growth characteristics of single post-feeding larvae and puparia of Calliphora vicina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) obtained from a controlled Nordiazepam study. Int. J. Legal Med. 118, 190–193 (2004).

Zou, Y. et al. Effect of ketamine on the development of Lucilia sericata (Meigen) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and preliminary pathological observation of larvae. Forensic Sci. Int. 226, 273–281 (2013).

Liu, X., Shi, Y., Wang, H. & Zhang, R. Determination of malathion levels and its effect on the development of Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius) in South China. Forensic Sci. Int. 192, 14–18 (2009).

George, K. A., Archer, M. S., Green, L. M., Conlan, X. A. & Toop, T. Effect of morphine on the growth rate of Calliphora stygia (Fabricius) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and possible implications for forensic entomology. Forensic Sci. Int. 193, 21–25 (2009).

Donovan, S. E., Hall, M. J. R., Turner, B. D. & Moncrieff, C. B. Larval growth rates of the blowfly, Calliphora vicina, over a range of temperatures. Med. Vet. Entomol. 20, 106–114 (2006).

Boatright, S. A. & Tomberlin, J. K. Effects of Temperature and Tissue Type on the Development of < I > Cochliomyia macellaria (Diptera: Calliphoridae). me 47, 917–923 (2010).

Anderson, G. S. Minimum and maximum development rates of some forensically important Calliphoridae (Diptera). J. Forensic Sci. 45, 824–832 (2000).

Byrd, J. H. & Allen, J. C. The development of the black blow fly, Phormia regina (Meigen). Forensic Sci. Int. 120, 79–88 (2001).

Hall, D. G. The Blowflies of North America (Thomas Say Foundation, 1948).

Byrd, J. H. & Castner, J. L. Insects of forensic importance. In Forensic Entomology: the Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations (eds Byrd, J. H. & Castner, J. L.) 88 (CRC, 2009).

Baqué, M., Filmann, N., Verhoff, M. A. & Amendt, J. Establishment of developmental charts for the larvae of the blow fly Calliphora vicina using quantile regression. Forensic Sci. Int. 248, 1–9 (2015).

Fournier, C., Jamoulle, O., Chadi, A. & Chadi, N. Severe benzodiazepine use disorder in a 16-Year-Old adolescent: A rapid and safe inpatient taper. Pediatrics 147, e20201085 (2021).

Noblesse, A. P., Meeds, A. W. & Weidner, L. M. Blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and the American diet: effects of fat content on blow fly development. J. Med. Entomol. 59, 1191–1197 (2022).

Lees, G., Beadle, D. J., Neumann, R. & Benson, J. A. Responses to GABA by isolated insect neuronal somata: Pharmacology and modulation by a benzodiazepine and a barbiturate. Brain Res. 401, 267–278 (1987).

Buckingham, S. D., Higashino, Y. & Sattelle, D. B. Allosteric modulation by benzodiazepines of GABA-gated chloride channels of an identified insect motor neurone. Invert. Neurosci. 9, 85–89 (2009).

Anthony, N. M., Harrison, J. B. & Sattelle, D. B. GABA receptor molecules of insects. In Comparative Molecular Neurobiology 172–209 (Birkhäuser Basel, 1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-7265-2_8.

Mattila, M. A. K., Larni, H. M. & Flunitrazepam A review of its Pharmacological properties and therapeutic use. Drugs 20, 353–374 (1980).

Hosie, A. M. & Sattelle, D. B. Allosteric modulation of an expressed homo-oligomeric GABA‐gated chloride channel of Drosophila melanogaster. Br. J. Pharmacol. 117, 1229–1237 (1996).

Sattelle, D. B., Lummis, S. C. R., Wong, J. F. H. & Rauh, J. J. Pharmacology of insect GABA receptors. Neurochem Res. 16, 363–374 (1991).

Robinson, T., MacAllan, D., Lunt, G. & Battersby, M. γ-Aminobutyric acid receptor complex of insect CNS: characterization of a benzodiazepine binding site. J. Neurochem. 47, 1955–1962 (1986).

Fremdt, H. et al. Kolymbari, Crete,. Influence of rohypnol and ethanol on succession and development of necrophagous insects. in Proceedings 6th Meeting of the European Association for Forensic Entomology (2008).

Baia, T. C., Campos, A., Wanderley, B. M. S. & Gama, R. A. The effect of flunitrazepam (Rohypnol ®) on the development of C Hrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and its implications for forensic entomology. J. Forensic Sci. 61, 1112–1115 (2016).

Boulkenafet, F. et al. Detection of benzodiazepines in decomposing rabbit tissues and certain necrophagic dipteran species of forensic importance. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 1691–1698 (2020).

Afifi, F. M., Abdelfattah, E. A. & El-Bassiony, G. M. Impact of using Sarcophaga (Liopygia) Argyrostoma (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) as a toxicological sample in detecting clonazepam for forensic investigation. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 12, 37 (2022).

Quijano-Mateos, A., Castillo-Alanis, A., Pedraza-Lara, C. S. & Bravo-Gómez, M. E. Evaluation of the effect of clonazepam and its metabolites on the life cycle of Megaselia scalaris (Loew) (Diptera: Phoridae). Sci. Justice. 64, 460–465 (2024).

Goff, M. L., Omori, A. I. & Goodbrod, J. R. Effect of cocaine in tissues on the development rate of Boettcherisca Peregrina (Diptera: Sarcophagidae). J. Med. Entomol. 26, 91–93 (1989).

Mullany, C., Keller, P. A., Nugraha, A. S. & Wallman, J. F. Effects of methamphetamine and its primary human metabolite, p-hydroxymethamphetamine, on the development of the Australian blowfly Calliphora stygia. Forensic Sci. Int. 241, 102–111 (2014).

Lü, Z. et al. Effects of ketamine on the development of forensically important blowfly Chrysomya megacephala (F.) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and its forensic relevance. J. Forensic Sci. 59, 991–996 (2014).

Simkiss, K., Daniels, S. & Smith, R. H. Effects of population density and cadmium toxicity on growth and survival of blowflies. Environ. Pollut. 81, 41–45 (1993).

Shelomi, M., Matern, L. M., Dinstell, J. M., Harris, D. W. & Kimsey, R. B. DEET (N,N-Diethyl‐meta‐toluamide) induced delay of blowfly landing and oviposition rates on treated pig carrion (Sus scrofa L). J. Forensic Sci. 57, 1507–1511 (2012).

Trivia, A. L. & De Carvalho Pinto, C. J. Analysis of the effect of cyclophosphamide and methotrexate on Chrysomya megacephala (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Forensic Sci. 63, 1413–1418 (2018).

Preußer, D., Bröring, U., Fischer, T. & Juretzek, T. Effects of antibiotics ceftriaxone and Levofloxacin on the growth of Calliphora vomitoria L. (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and effects on the determination of the post-mortem interval. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 81, 102207 (2021).

De Carvalho, L. M. L., Linhares, A. X. & Badan Palhares, F. A. The effect of cocaine on the development rate of immatures and adults of Chrysomya Albiceps and Chrysomya putoria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and its importance to postmortem interval estimate. Forensic Sci. Int. 220, 27–32 (2012).

Oliveira, H. G., Gomes, G., Morlin Jr, J. J., Zuben, V., Linhares, A. X. & C. J. & The effect of Buscopan® on the development of the blow fly Chrysomya megacephala (F.) (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Forensic Sci. 54, 202–206 (2009).

Angier, M. K., Saenz, S. R., Ritter, R. M. & Lewis, R. J. Identification and Quantification of 22 Benzodiazepines in Postmortem Fluids and Tissues Using UPLC/MS/MS. (2018). https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/data_research/research/med_humanfacs/oamtechreports/201801.pdf

Clinical Laboratory Reference. Table of Cutoff Toxicity for Drugs of Abuse. (2012). https://www.clr-online.com/CLR201213-Table-of-Cutoff-Toxicity-DOA.pdf

R CORE TEAM 2022. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. R version 4.2.1 (2022-06-23) ed (2022).

Kay, M., Elkin, L., Higgins, J. & Wobbrock, J. 2021. ARTool: Aligned Rank Transform for Nonparametric Factorial ANOVAs. R package version 0.11.1. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.594511.

Wobbrock, J., Findlater, L., Gergle, D. & Higgins, J. The Aligned Rank Transform for Nonparametric Factorial Analyses Using Only ANOVA Procedures. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 143–146 (2011).

Elkin, L., Kay, M., Higgins, J. & Wobbrock, J. An Aligned Rank Transform Procedure for Multifactor Contrast Tests. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3472749.3474784

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: 'ggplot2' Based Publication Ready Plots. R package version 0.6.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the ND EPSCoR State STEM Seed Award 2023. We also acknowledge RO1567-IBB09/2025 for supporting TS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LI: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MW: Methodology. TS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iancu, L., Wellens, M. & Sahlean, T. Effects of clonazepam and flunitrazepam on the development cycle of Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy 1830 and their forensic implications. Sci Rep 15, 22773 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05766-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05766-8