Abstract

Coronary artery calcification score (CACS), also known as the Agatston score, is a significant prognostic tool for cardiovascular disease (CVD) that utilizes computed tomography (CT). We expand our previously proposed algorithm, Residual-block Inspired Coordinate Attention U-Net (RICAU-Net), to evaluate its generalizability on CT data from previously unseen scanners for lesion-specific CAC segmentation. The multi-vendor datasets were 1,108 CT scans acquired by Siemens, GE, Philips, and Toshiba. We created four groups of datasets, using data from the three scanners as the training and validation sets, while the last one as the test set to evaluate the algorithm on data from previously unseen scanners. RICAU-Net was trained using the datasets for automatic lesion-specific CAC segmentation and calcium scoring. The performance of lesion-specific segmentation and calcium scoring were evaluated using per-lesion Dice scores and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). And Bland-Altman plot analysis was conducted to examine the agreement between the CAC score derived from the prediction results and the ground truth. The proposed algorithm exhibited a mean absolute difference of less than 5% between the per-lesion Dice scores of the validation and test sets, indicating good generalizability on test sets comprised of data from unseen scanners during the training and validation phases. ICC analysis demonstrates that the Agatston scores calculated using predictions from RICAU-Net and manual segmentation exhibited excellent reliability at the per-patient level across all groups with ICC and 95% confidence intervals: 0.95 (0.95–0.96), 0.99 (0.99–1.00), 0.99 (0.99–0.99), and 1.00 (0.99–1.00) for group 1, 2, 3, and 4 respectively. Our algorithm demonstrates generalized performance on data from previously unseen scanners, making it potentially more suitable and practical for real-world clinical settings, where it will encounter diverse scanners from various organizations. Furthermore, a feasibility study using non-contrast chest CT scans indicates that the performance of our cardiac CT-trained algorithm on chest CT images was acceptable to a certain extent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery calcification score (CACS) is a well-established measure of coronary artery disease (CAD)1,2,3,4,5demonstrating strong utility in prognosis of major adverse cardiovascular events6,7. Cardiovascular guidelines in several prominent nations advise utilizing CACS to discriminate the need for treatment in intermediate-risk groups8highlighting the importance of CACS in modern clinical practice. The current standard for CACS evaluation is manual calculation of computed tomography (CT) slices by highly trained physicians9,10. This is a time-consuming process that requires substantial experience. The increasing healthcare burden of CAD, and demand for CACS to guide clinical management, is an issue which may be mitigated by the recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI).

Modern AI technologies such as deep learning (DL) and machine-learning (ML) based approaches have shown significant promise in various aspects of healthcare, ranging from genomics and pathology to clinical imaging11. Several fields are exploring the application of DL and ML in clinical practice to streamline assessments and increase efficiency11,12. Implementation of DL also allows for a form of standardization, as a single algorithm can be uniformly applied across large datasets. In this regard, deep learning algorithms have demonstrated their ability to identify calcification in the coronary arteries and to accurately automate the CACS calculation13,14,15,16,17. However, vigorous training and validation of DL-based models are required, due to the possibility of variation between CT machines from different vendors18. Previous research on inter-scanner CACS found reduced variation when using a single software compared to scanner specific software19further highlighting the importance of robust algorithms. Therefore, given the diverse options of CT scanners, it is imperative that DL algorithms for CACS are trained to account for nuances between vendors. This approach aims to achieve generalized performance on previously encountered data from diverse CT machines from different vendors while also ensuring consistently good performance on data from previously unseen CT machine vendors.

We aim to expand on previously proposed Residual-block Inspired Coordinate Attention U-Net (RICAU-Net)20built upon U-Net by addition of Residual-block Inspired Coordinate Attention (RICA) blocks and Coordinate Attention (CA)21 modules. Ronneberger et al.22 demonstrated increased performance of U-Net relative to other algorithms with its improved prediction of individual pixel class through context, and modest training time requirements. RICAU-Net outperformed several other U-Net based algorithms in segmenting lesion-specific coronary artery calcium (CAC) and evaluating CACS in all coronary vessels examined: the left main coronary artery (LM), left anterior descending artery (LAD), left circumflex artery (LCX), and right coronary artery (RCA). To ensure that the proposed RICAU-Net al.gorithm can be universally applied, we utilized a multi-vendor dataset comprising 1,108 non-contrast cardiac CT scans acquired from Siemens, GE, Philips, and Toshiba. We organized these scans into four groups: the data from three of the scanners served as the training and validation sets, while the remaining scanner’s data was designated as the test set. This approach allows us to evaluate the generalizability and performance of RICAU-Net on previously unseen scanners.

Results

Automated per-lesion segmentation performance

The per-lesion CAC segmentation results of RICAU-Nets across all four groups were evaluated and presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2. Generally, CAC in LM exhibited the lowest per-lesion Dice scores, which was attributed to the high class-imbalance issue in the number of CT images containing calcium lesions, as detailed in Table 2. CAC in LM exhibited the lowest per-lesion Dice scores on validation and test sets for group 1, 2, and 3, as well as on the validation set for group 4. However, in the test set for group 4, the per-lesion Dice score of CAC in LM (89.90) was higher than that of CAC in LCX (83.78). CAC in LCX showed the largest absolute difference in group 1, 2, and 3 with values of 9.68, 4.87, and 17.75 respectively. Conversely, CAC in LM exhibited the largest absolute difference in group 4 (15.11). This discrepancy may be attributed to the small sample sizes of CAC lesions in the test set for group 4. The sample sizes of CAC lesions in this test set were at least ten times smaller than those in the test sets from the other groups. Such a limited sample size was insufficient to adequately evaluate the generalized performance of the algorithm, resulting in its failure to exhibit trends similar to those observed in the other three groups. The mean absolute differences were below 5% for groups 1 (4.71), 2 (3.14), and 4 (4.87), indicating that the lesion-specific segmentation performance of RICAU-Net for the validation and test sets was comparable across these groups, thereby demonstrating the model’s good generalizability on the test set acquired from previously unseen scanners in relation to the training and validation datasets. However, group 3 exhibited a mean absolute difference of 8.05, with the largest absolute difference observed for CAC in LCX (17.75). This is primarily due to the distribution of the dataset across the training, validation, and test sets in group 3, where the test set contained a volume of data comparable to that of the training set. The smallest absolute differences were observed for CAC in LAD in groups 2 and 4, and for CAC in RCA in groups 1 and 3. This correlation arises because the per-lesion Dice scores were highly associated with the volume of data. CAC in LAD and RCA had the two largest numbers of lesions across the training, validation, and test sets for all groups. The five-fold cross-validation results of the RICAU-Net, presented in Supplementary Table S3, exhibited a trend similar to that observed in Table 1. Unlike the per-lesion Dice scores, the mean and standard deviations (SD) (in parentheses) of the per-lesion 95th percentile of the Hausdorff distance (HD95) between the validation and test sets across all four groups demonstrated a different trend. CAC in LM exhibited the smallest HD95 of 0.05 (0.30) and 0.31 (1.31) in the validation set for groups 2 and 4, indicating a high degree of similarity between the ground truths and the predictions. CAC in RCA showed the smallest absolute difference in group 3, with a value of 0.02 (2.09). Conversely, CAC in LM exhibited the largest absolute difference in group 2, with a value of 2.18 (4.40). The mean absolute differences for each group were 0.49 for group 1, 1.04 for group 2, 0.83 for group 3, and 0.49 for group 4, indicating that all groups exhibited a high degree of similarity between the ground truths and predictions from the validation and test sets. These results further reinforce our study about RICAU-Net’s good generalizability on the test set acquired from previously unseen scanners in relation to the training and validation datasets.

Figure 1 illustrates the per-lesion segmentation performance of RICAU-Nets across eight patients (two patients per group), representing the algorithm’s diverse prediction results. It is noticeable that the images in Fig. 1 majorly exhibited the per-lesion Dice scores above 90%. However, four images showed the common misclassifications in the segmentation task. In Fig. 1c, the non-coronary artery calcified area was incorrectly segmented as a mixture of CAC in LAD and LCX, resulting in the per-lesion Dice scores of 94.18 for CAC in LAD and 65.56 for CAC in LCX respectively. Figure 1e also indicated that the algorithm misclassified the non-coronary artery calcified area as CAC in LCX, while the per-lesion Dice scores for CAC in LAD and RCA remained at 100. In Fig. 1f, CAC in LM was misclassified as CAC in LAD, leading to the per-lesion Dice score of 0 for CAC in LM, although the lesion was still recognized as being located in the coronary artery. Finally, Fig. 1h showed that the algorithm failed to segment one LAD lesion, resulting in a decrease in the per-lesion Dice score for CAC in LAD to 85.38. Overall, the algorithm demonstrated the generalized performance across the diverse images from the test sets, which were obtained from the scanners not included in the training and validation sets. To further validate the generalizability of the algorithm, the segmentation performance for images containing noise, noise combined with CAC, and artificial implants alongside CAC were visualized in Fig. 2. In addition, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM)23 was employed to illustrate the significance of specific classes in the final decision of the model through attention maps. The darker red areas on the attention maps indicate a higher level of importance. In Fig. 2, the Grad-CAM was utilized to generate the attention maps for the bone category, as noise, artificial implants, and aortic calcium were annotated as bone in this study. All the images in Fig. 2 exhibited high Dice scores for bone segmentation (98.76, 98.14, and 99.73 respectively), with darker red areas on the bone, noise, and artificial implants in the Grad-CAM images. This finding demonstrated that the algorithm exhibited a high level of confidence in its decisions when segmenting these elements as bone, not as CACs.

Visualization of the per-lesion segmentation performance of RICAU-Nets on a variety of input images. The input images were sourced from eight patients, with two patients represented in each group. Ground truths and predictions from the test sets are presented for group 1 (a, b), in group 2 (c, d), in group 3 (e, f), and in group 4 (g, h). The per-lesion Dice scores for each image are as follows: LM: 99.70%, LAD: 97.96% for (a); LCX: 99.20% for (b); LM: 99.32%, LAD: 94.18%, LCX: 65.56% for (c); LAD: 100%, LCX: 95.24%, RCA: 100% for (d); LAD: 100%, RCA: 100% for (e); LAD: 81.63% for (f); LM: 98.73%, LAD: 100% for (g); LAD: 85.38% for (h). Common misclassifications in the segmentation task are observed in (c, e, f, h). The corresponding calcium lesions are displayed in the colored boxes, with their names highlighted in the top right corner of the images.

Visualization of the per-lesion segmentation performance of RICAU-Nets on images containing noise (a), noise and CAC (b), and artificial implants with CAC (c). The lesions are zoomed-in in the images. The Grad-CAM23 attention maps were generated with respect to the bone category, as both noise and artificial implants were categorized within this category. The per-lesion Dice scores for each image are as follows: background: 99.97%, bone: 98.76% for (a); background: 99.96%, bone: 98.14%, RCA: 90.24% for (b); background: 99.98%, bone: 99.73%, LAD: 100% for (c). The red heatmap areas indicating noise and artificial implants demonstrated that RICAU-Nets effectively distinguished between these elements and calcium lesions.

Automated per-lesion and per-patient calcium scoring performance

Table 3 presents intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for per-lesion (per artery) and per-patient Agatston scores calculated from both AI automated segmentation and manual segmentation using the test sets across all four groups, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). At the per-patient level, RICAU-Nets achieved ICCs of 0.95 and above across all four groups. At the per-lesion level in group 1, the ICCs of per-lesion Agatston score demonstrated excellent reliability (> 0.9) for CAC in LAD, LCX, and RCA. In contrast, CAC in LM exhibited moderate reliability, with ICC of 0.66 (95% CI: 0.60–0.72). Similar results were observed in group 2 and 3, where the ICCs of per-lesion Agatston scores also showed excellent reliability (> 0.9) for CAC in LAD, LCX, and RCA. However, in group 2 and 3, CAC in LM exhibited good reliability (ICC of 0.78 and 0.75 respectively). In group 4, per-lesion Agatston scores for all lesions demonstrated excellent reliability (> 0.9). Nonetheless, as indicated in Tables 2 and 4, group 4 had the highest class-imbalance ratio between the training/validation sets and the test set, as the test set consisted of Philips scanner data, which included only 18 patients (1,060 images).

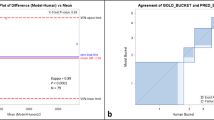

Figure 3 illustrates the Bland-Altman plots for per-patient Agatston scores calculated using both AI automated segmentation and manual segmentation for each group. Figure 3 shows that the majority of the per-patient Agatston score differences between the AI automated segmentation and manual segmentation fall within the ± 1.96 standard deviation (SD) range. This range indicates where the 95% of the differences between the two measurements are expected to lie within24,25,26. The per-patient Bland-Altman plots demonstrated good agreement across all groups. Furthermore, all plots exhibited negative mean differences that were close to zero between the ground truth and the predictions (group 1: -4.77, group 2: -3.44, group 3: -5.25, group 4: -2.66). This indicated that per-patient Agatston scores derived from the algorithm and the manual segmentation were closely aligned, although the per-patient Agatston scores from the algorithm slightly higher. The Bland-Altman plots for per-lesion Agatston scores and their respective logarithmic transformed plots are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. The per-lesion Bland-Altman plots showed a trend similar to that of the per-patient plots with the exception of CAC in LM. This is because the per-lesion Bland-Altman plot results are highly correlated to the per-lesion Dice scores of the algorithm. The possible reasons for the diverging shapes of CAC in LM plots are further discussed in the Supplementary information.

Feasibility study: automated per-lesion segmentation performance on chest CT images

The per-lesion CAC segmentation results of cardiac CT-trained RICAU-Nets on chest CT test sets were evaluated and presented in Table 1. For the extension study utilizing the same training and validation sets as group 2 (GE, Philips, and Toshiba), the non-contrast chest CT scans acquired from Siemens scanners were employed as the test set. In this scenario, CAC in LM + LAD achieved the highest per-lesion Dice score of 72.07%, whereas CAC in LCX recorded the lowest per-lesion Dice score of 10.54%. Similar results were observed in the extension study using the same training and validation sets as group 3 (Siemens, Philips, and Toshiba), with the non-contrast chest CT scans acquired from GE scanners as the test set. In this group, CAC in LM + LAD exhibited the highest per-lesion Dice score of 64.36%, while the lowest per-lesion Dice score of 50.06% was recorded for CAC in LCX. The per-lesion Dice score for CAC in LCX based on chest CT scans from Siemens scanners (10.54%) was significantly lower than that from GE scanners (50.06%). This observation may be attributed to the higher numbers of false positive and false negative pixels compared to true positive pixels in the test set from Siemens scanners. This suggested that the algorithm struggled to differentiate CAC in LCX from CAC in other arteries or from calcified areas in non-coronary arteries. Overall, the per-lesion Dice scores for the chest CT test sets were significantly lower than those for the cardiac CT test sets, which can be due to the clear visualization of the lung and the weak contrast surrounding the heart and associated coronary arteries resulting from the nature of the chest CT images.

Supplementary Fig. S2 illustrates the per-lesion segmentation performance of RICAU-Nets on non-contrast chest CT images across four patients, with two patients from each scanner. It is evident that the characteristics of the chest CT images differs from those of the cardiac CT images when comparing the images in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2.

Discussion

In our previous study20RICAU-Net and the weighted Focal LogDice loss demonstrated its superior performance in the segmentation of small and sparse lesions compared to six other U-Net based networks used in various medical segmentation tasks. Therefore, this study employed the same algorithm, training environments, and hyperparameters as our previous research to further evaluate the generalizability of the proposed algorithm for automated lesion-specific CAC segmentation and calcium scoring using the multi-vendor dataset. This dataset comprised non-contrast cardiac CT scans from 1,108 participants, acquired using four different scanners with 14 distinct model numbers. A total of four groups were generated from the multi-vendor dataset to evaluate the generalizability of the proposed algorithm; each group included training and validation sets from three scanners, with the test set derived from the scanner not used for training and validation sets. This approach ensured that the model’s performance was evaluated using completely unseen scanner data. RICAU-Net achieved the lowest per-lesion Dice score for CAC in LM in group 1, 2, and 3 with scores of 59.35, 60, and 59.41 respectively. These results reflected a consistent pattern observed in our previous study. The Agatston scores, calculated using the predictions from RICAU-Net and the manual segmentation, demonstrated excellent reliability at the per-patient level (ICC > 0.9). At the per-lesion level, the Agatston scores for CAC in LAD, LCX, and RCA exhibited excellent reliability, while the Agatston score for CAC in LM showed moderate to good reliability. This discrepancy is mainly attributed to the high class-imbalance present in the dataset groups. Grad-CAM attention maps were visualized for images containing noise, images with both noise and CAC, and images with artificial implants, demonstrating that the algorithm effectively segmented these structures as bone. The mean absolute difference was below 5% for group 1, 2, and 3, indicating good generalizability on test sets consisted of previously unseen scanner images. We also conducted a feasibility study using non-contrast chest CT scans as the test set to further validate the generalizability of the cardiac CT-trained algorithm. The overall per-lesion Dice scores for the chest CT test sets were significantly lower than those for the cardiac CT test sets, as the algorithm was only trained on the cardiac CT scans, and the characteristics of cardiac CT and chest CT are inherently different. The per-lesion Dice scores for all lesions on chest CT scans were above 50%, except for CAC in LCX from Siemens scanners, which only recorded the per-lesion Dice score of 10.54%. The highest per-lesion Dice score was 72.07% for CAC in LM + LAD. Although this study was conducted with a smaller dataset and simpler annotations (CAC in LM combined with CAC in LAD), the two extension studies demonstrated the feasibility of segmenting CAC on chest CT scans using the cardiac CT-trained algorithm. Performance could be further improved by analyzing the feature differences between chest CT and cardiac CT, and implementing appropriate image augmentation methods during the training phase. Overall, we demonstrated that the good generalizability of RICAU-Net makes the model applicable to new or unseen scanner images.

However, this study still has two limitations. First, the data distribution was highly imbalanced both within each lesion and across each group. Among the lesions, CAC in LM was the least prevalent in all groups. Among the groups, the test set for group 4 included the smallest number of patients. Second, the study could be further analyzed at the intra-scanner level to evaluate the generalizability of RICAU-Net based on the distinct model numbers of the scanners, provided that an adequate number of patient data with various model numbers are collected.

In conclusion, our study validated the generalizability of RICAU-Net for automated lesion-specific CAC segmentation and calcium scoring using the multi-vendor dataset. The algorithm exhibits generalized performance on previously unseen scanner images, making it more suitable and practical for real-world clinical settings, where it will encounter a variety of scanner images from different organizations. In the future, we aim to further validate the generalizability of the algorithm with additional datasets for both intra-scanner and inter-scanner analyses.

Methods

Multi-vendor scanner CT images

In this study, a total of four different scanners with 14 model numbers were utilized for non-contrast cardiac CT scan screening of 1,108 participants to visualize coronary artery calcification. The scanners included models from GE Medical Systems (LightSpeed VCT, Optima CT660, GMS Revolution_RC, Revolution CT), Siemens (Sensation 64, SOMATOM Definition Flash, SOMATOM Definition, SOMATOM Force, SMS Definition, Sensation Cardiac 64), Philips (iCT 256, Brilliance 64, Ingenuity CT), and Toshiba (Aquilion ONE). As listed in Table 4, the Toshiba CT scanner was employed to screen 496 patients, representing the largest cohort. However, only 56% of these patients exhibited CAC. In contrast, over 94% of the patients screened by the other scanners exhibited CAC. Notably, Philips was used to screen the smallest number of patients which included only 18 patients. The study was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of SingHealth, Singapore (IRB 2022–2521). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Central Institutional Review Board of SingHealth waived the need to obtain informed consent.

Dataset

Five clinically trained specialists manually annotated CAC lesions using six categories: background, bone (including noise, artificial implants, calcium lesions in the aorta, ramus intermedius artery, aortic valve, and mitral valve), CAC in LM, LAD, LCX, and RCA. This process was undertaken to create lesion-specific ground truth masks for multi-vendor scanner CT images. Prior to preparing the dataset, we first classified the manufacturers/scanners of the data by examining the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) tags. Utilizing this information, we categorized the entire dataset into four vendors: GE, Philips, Siemens, and Toshiba scanners. To evaluate the generalizability of the lesion-specific CAC segmentation algorithm, the multi-vendor scanner images, along with their corresponding annotations, were divided into four groups, as listed in Table 2. Each group consisted of training and validation datasets from three different manufacturers/scanners, with a ratio of 80:20, respectively. The test dataset was sourced from the fourth manufacturer that was not included in the training and validation datasets, allowing for the evaluation of the model’s performance on completely unseen scanner data. Throughout this process, we established a total of four groups of multi-vendor datasets. Additionally, to further evaluate the generalizability of the algorithm, CT images containing noise and artificial implants were also included in the dataset.

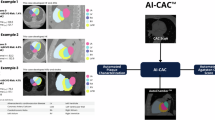

Automatic lesion-specific CAC segmentation algorithm

In our previous study20we proposed RICAU-Net and Focal LogDice loss for the segmentation of small and sparse lesions. As illustrated in Fig. 4, RICAU-Net utilized CA in the form of RICA blocks in the encoder (inspired by the residual block in ResNet27) and CA modules in the decoder to emphasize the positional information of the small and sparse CAC lesions. The details of the CA module and RICA block are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S3. Focal LogDice loss served as a customized combo loss function designed to address the high class-imbalance issue with small objects20,28,29. RICAU-Net demonstrated its superior performance in lesion-specific segmentation compared to other U-Net based networks for medical segmentation task, including U-Net22Nested U-Net30Attention U-Net31SA U-Net32ResUNet + + 33, and VGG16 U-Net. Consequently, this study employed RICAU-Net to validate its lesion-specific segmentation and generalization performance across various groups of the multi-vendor scanner datasets. The performance of lesion-specific segmentation was evaluated using per-lesion Dice scores and the 95th percentile of the Hausdorff distances (HD95) for each lesion. The per-lesion Dice scores quantify the resemblance between the predicted masks and the ground truth. Dice score was calculated by comparing the ground truth with the algorithm’s predicted results using the formula 2TP / (2TP + FP + FN), where TP represents the number of true positive pixels, FP represents the number of false positive pixels, and FN represents the number of false negative pixels. The HD95 metric measures the 95th percentile of distances between two sets of points: the predicted masks and the ground truth. For HD95, we calculated the metric at the per-lesion level by utilizing the Python package developed by Jia34. The generalization performance was evaluated by calculating the absolute difference in per-lesion Dice scores and per-lesion HD95 between the validation and test sets. Moreover, in addition to the per-lesion segmentation results presented in Table 1, we also conducted a five-fold cross-validation with a holdout test set to fully optimize the use of the multi-vendor dataset and mitigate the risk of overfitting. This experiment is detailed in Supplementary Figure S4, and the corresponding per-lesion segmentation results for the five-fold cross-validation are presented in Supplementary Table S3. The per-lesion segmentation performance of RICAU-Net, utilizing the multi-vendor dataset, was compared with that of U-Net and Nested U-Net, as presented in Supplementary Table S4. These two networks were chosen because RICAU-Net and the other two demonstrated the highest LM Dice scores in our previous study20. The two networks were trained using same training condition with the weighted Focal LogDice loss.

Preprocessing and implementation

This study employed the same preprocessing techniques and implementation details as those used in our previous study20. All CT scans were originally in 3D images. The 3D images were sliced in the axial plane, and were clipped to the raw Hounsfield Units (HU) of [-150, 230]. The processed 2D images had dimensions of 512 × 512 pixels, with slice thicknesses of 2.5 mm, 3.0 mm, and 5.0 mm (only one CT scan from the GE Lightspeed VCT model had a slice thickness of 5.0 mm). The pixel-spacing varied from 0.258 mm to 0.765 mm. All images were normalized to a range of floating-point numbers [0, 1], followed by an on-the-fly image augmentation of the training images. Augmentation methods included random rotations of -10◦, -5◦, + 5◦, and + 10◦, random center crops of 300 × 300 and 400 × 400 pixels with padding to 512 × 512, as well as the addition of random noise, including Gaussian blur, Gaussian noise, and salt-and-pepper noise.

Four CPU cores (16GB) from AMD EPYC 7742 processor and two NVIDIA DGX-A100 graphics processing units (GPUs) with 40GB of RAM each were utilized to train RICAU-Nets from scratch. The deep learning framework utilized a Pytorch container image, version 23.06 (2.1.0a0 + 4136153), with Python 3.10.6. RIAU-Net was trained for 100 epochs in each group, using the following hyperparameters: the weighted Focal LogDice loss function, a batch size of 16, and the cosine annealing warm restart learning rate scheduler with the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate = 1e-12, maximum learning rate = 1e-4, first restart epochs = 50, warmup restart epochs = 5, maximum learning rate scale factor = 0.5 at every restart)35,36.

Automatic calcium quantification

The Agatston score is the multiplication of the weighting factor and the area of the calcification in the coronary arteries with HU above 13037. The weighting factor was determined based on the highest HU in the area of calcification: weighting factor 1 for 130–199 HU, weighting factor 2 for 200–299 HU, weighting factor 3 for 300–399 HU, and weighting factor 4 for ≥ 400 HU38. The overall per-lesion and per-patient levels calcium segmentation and quantification processes are illustrated in Fig. 4. If multiple calcium lesions were present in the same coronary artery, the Agatston score for each CAC was calculated independently and then summed as shown in Fig. 5.

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was employed to evaluate the reliability of the automated process for calculating the per-lesion and per-patient Agatston scores. This evaluation was based on the prediction results from RICAU-Nets and manually annotated ground truth. In addition, Bland-Altman plots were utilized to examine the agreement between the per-patient Agatston scores derived from the prediction results and those obtained from the manual segmentation masks.

Feasibility study: extension to using chest CT images

The feasibility study employed non-contrast chest CT scans as the test set to further validate the generalizability of the cardiac CT-trained algorithm, as the nature of the cardiac and chest CT images are inherently different, yet both contain CACs. Chest CT scan is primarily performed to assess lung conditions, while cardiac CT scan is specialized for imaging the heart and coronary arteries. Consequently, chest CT scans are not capable of providing detailed images of the structures of the heart, making them less suitable for identifying coronary artery calcium (CAC) as they struggle to detect smaller or subtle CACs. Additionally, cardiac CT generally provides higher-resolution images, as it focuses specifically on the heart rather than the entire chest. Cardiac CT scans are typically electrocardiography (ECG) gated to minimize motion artifacts from the heart and enhance the clarity of the coronary arteries39. Therefore, while chest CT can be used to detect CAC and calculate the Agatston score if CACs are present, it is less accurate, sensitive, detailed, and precise for assessing CAC and the Agatston score compared to cardiac CT40,41. In general, chest CT scans are more available than cardiac CT scans, if a cardiac CT-trained model can effectively detect CACs on chest CT images, it may be beneficial for patients to calculate Agatston scores using previously obtained chest CT scans as a preventive measure against coronary artery disease39. Furthermore, if the model demonstrates strong performance, it would reduce the need for additional computational resources required to train a separate model specifically for chest CT images. The experiment was conducted using the same algorithm, preprocessing methods, and implementation details, with the exception of HU clipping. No specific techniques were employed for the chest CT scans, such as enhancing the contrast around the heart and coronary arteries, denoising, or adding the chest CT images into the training and validation sets. For all the cardiac (training and validation sets) and chest (test set) CT images, the raw HU values were clipped to the range of [0, 255]. In the feasibility study, non-contrast chest CT scans from 80 participants were included. The scans were obtained from two different scanners with four model numbers. The scanners comprised models from GE Medical Systems (Revolution CT, Discovery CT750 HD) and Siemens (SOMATOM Definition Flash, SOMATOM Force). For the chest CT scans, CAC in LM was combined with CAC in LAD due to the challenges associated with identifying them separately on the chest CT scans. The chest CT scans acquired by Siemens and GE were tested using the RICAU-Nets trained on the cardiac CT training and validation datasets from group 2 (GE, Philips, and Toshiba) and group 3 (Siemens, Philips, and Toshiba), respectively. During the training and validation processes, CAC in LM and LAD in the ground truth masks of the cardiac CT scans were combined. See Supplementary Table S1 in the Supplementary Information for the characteristics of the chest CT test dataset.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available, as CT data and DICOM headers contain patient information, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mori, H. et al. Coronary artery calcification and its progression: what does it really mean? JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging. 11, 127–142 (2018).

Wong, N. D. et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment: an American society for preventive cardiology clinical practice statement. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 10, 100335 (2022).

Madaj, P. & Budoff, M. J. Risk stratification of non-contrast CT beyond the coronary calcium scan. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 6, 301–307 (2012).

Hata, N. et al. Clinical significance of coronary artery calcification. Int. Angiol. 13, 281–285 (1994).

Shemesh, J. et al. Coronary calcium by spiral computed tomography predicts cardiovascular events in high-risk hypertensive patients. J. Hypertens. 22, 605–610 (2004).

Abuzaid, A. et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk of cardiovascular events without established coronary artery disease: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Coron. Artery Dis. 32, 317–328 (2021).

Sarwar, A. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2, 675–688 (2009).

Golub, I. S. et al. Major global coronary artery calcium guidelines. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 16, 98–117 (2023).

Kramer, C. K. et al. Coronary artery calcium score prediction of all cause mortality and cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 346, (2013).

Shreya, D. et al. Coronary artery calcium score-a reliable indicator of coronary artery disease? Cureus 13, (2021).

Pinto-Coelho, L. How artificial intelligence is shaping medical imaging technology: a survey of innovations and applications. Bioengineering 10, 1435 (2023).

Najjar, R. Redefining radiology: a review of artificial intelligence integration in medical imaging. Diagnostics 13, 2760 (2023).

Ma, J. & Zhang, R. Automatic calcium scoring in cardiac and chest CT using DenseRAUnet. arXiv preprint arXiv.11392, (2019).

Hong, J. S. et al. Automated coronary artery calcium scoring using nested U-Net and focal loss. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 1681–1690 (2022).

De Vos, B. D. et al. Direct automatic coronary calcium scoring in cardiac and chest CT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 38, 2127–2138 (2019).

Lessmann, N. et al. Automatic calcium scoring in low-dose chest CT using deep neural networks with dilated convolutions. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 37, 615–625 (2017).

Shahzad, R. et al. Vessel specific coronary artery calcium scoring: an automatic system. Acad. Radiol. 20, 1–9 (2013).

Oh, J. H., Choi, S. P., Wee, J. H. & Park, J. H. Inter-scanner variability in Hounsfield unit measured by CT of the brain and effect on gray-to-white matter ratio. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 37, 680–684 (2019).

Ghadri, J. R. et al. Inter-scan variability of coronary artery calcium scoring assessed on 64-multidetector computed tomography vs. dual-source computed tomography: a head-to-head comparison. Eur. Heart J. 32, 1865–1874 (2011).

Park, D. et al. RICAU-Net: Residual-block Inspired coordinate attention U-Net for segmentation of small and sparse calcium lesions in cardiac CT. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.06993, (2024).

Hou, Q., Zhou, D. & Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 13713–13722. (2021).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9 part III 18. (Springer, 2015).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 618–626. (2017).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 327, 307–310 (1986).

Giavarina, D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochemia Med. 25, 141–151 (2015).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 8, 135–160 (1999).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 770–778. (2016).

Lin, T. Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2980–2988. (2017).

Wong, K. C., Moradi, M., Tang, H. & Syeda-Mahmood, T. 3d segmentation with exponential logarithmic loss for highly unbalanced object sizes. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2018: 21st International Conference, Granada, Spain, September 16–20, Proceedings, Part III 11.612–619 (Springer, 2018).

Zhou, Z., Rahman Siddiquee, M. M., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support: 4th International Workshop, DLMIA and 8th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2018, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2018, Granada, Spain, September 20, 2018, Proceedings 4. 3–11 (Springer, 2018).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03999, (2018).

Guo, C. et al. Spatial attention u-net for retinal vessel segmentation. In., 25th international conference on pattern recognition (ICPR). (IEEE, 2021), 1236–1242. (2020).

Jha, D. et al. IEEE,., Resunet++: An advanced architecture for medical image segmentation. In 2019 IEEE international symposium on multimedia (ISM). 225–2255. (2019).

Jia, J., Staring, M. & Stoel, B. C. seg-metrics: a Python package to compute segmentation metrics. medRxiv 2002. 2022.24303215 (2024).

He, T. et al. Bag of tricks for image classification with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 558–567. (2019).

Loshchilov, I., Hutter, F. & Sgdr Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.03983, (2016).

Members, T. F. et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European society of cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 34, 2949–3003 (2013).

Agatston, A. S. et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 15, 827–832 (1990).

Hughes-Austin, J. M. et al. Relationship of coronary calcium on standard chest CT scans with mortality. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging. 9, 152–159 (2016).

Polonsky, T. S. et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. Jama 303, 1610–1616 (2010).

Kirsch, J. et al. Detection of coronary calcium during standard chest computed tomography correlates with multi-detector computed tomography coronary artery calcium score. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 28, 1249–1256 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Medical Research Council (NMRC) of Singapore (grant numbers NMRC/CG2/001a/2021NHCS, CG21APR1006 and TA21nov-0001), SingHealth-Duke-NUS ACP Philanthropy grant (HRDUK230600) and SingHealth-Duke-NUS ACP NCRS grant (07/FY2021/P2/12-A93). The computational work was fully supported and performed on resources of the National Supercomputing Centre (NSCC), Singapore (https://www.nscc.sg), and CHROMA in SingHealth Tower, SingHealth, Singapore (https://www.singhealth.com.sg).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this paper. D.P. and L.B. conceived the previously proposed deep learning algorithm and the loss function. D.P. conducted the experiments and analysis with support from L.B. J.N., Y.Z., and C.S.A.T. annotated the data. J.N., Y.Z., C.S.A.T., and X.W. verified the analysis. D.P. and J.N. wrote the manuscript in consultation with G.G.Y.L., L.Z., S.K.G.O., D.S.W.T., and L.B. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided critical feedback.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, D., Ng, J., Zhong, Y. et al. Evaluating the generalizability of an automated coronary artery calcium segmentation and scoring algorithm using multi-vendor dataset. Sci Rep 15, 21744 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05785-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05785-5