Abstract

This study investigates the application of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite to reduce Cr(VI) under visible light in the presence of citric acid The photogenerated electrons could easily be transferred from GO to ZnO/CuO species via interfacial charge transfer in the presence of metal oxides and graphene oxide. UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy showed that charge carriers were formed in response to visible light absorption. The effect of different operating parameters, including photocatalyst dose, pH, and initial Cr(VI) concentration, was systematically evaluated during the photocatalytic process. The ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite exhibited a 97% reduction in hexavalent chromium (10 ppm) within 40 min at pH 5, resulting in greater efficiency than the pristine ZnO/CuO (65%), and ZnO (7%) materials. The ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite displayed excellent stability over six cycles, highlighting its potential for practical applications. The synthesized photocatalyst was characterized using XRD, FTIR spectroscopy, SEM, and EDX. Tert-butyl alcohol, hydroquinone, sodium oxalate, acetone, and EDTA were investigated as scavengers in reducing Cr(VI) to Cr(III). In the presence of tert-butyl alcohol, 74% chromium reduction was observed, while with other compounds, the chromium reduction rate was 99%. Finally, the result shows that ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite is an efficient semiconductor with a better visible light response and a smaller band edge (2.48 eV) than ZnO (3.2 eV) and ZnO/CuO (2.65 eV) can be effectively used to reduce metal pollutants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increase in population and the rapid growth of industries and mining, a wide range of heavy metals such as (Cr, Sb, Ni, As, Hg, Pb, etc.) enter the metabolic system of aquatic and animal life; It threatens the environment and human health1. Unlike organic pollutants, heavy metals are not biodegradable. They easily enter the food chain and accumulate in the bodies of living organisms. The accumulation of heavy metals in the human body causes dizziness, headache, high blood pressure, skin staining, anemia, etc. Chromium pollution has become a key issue in aquatic ecosystems due to mining, plating, pigment production, wood preservation, tanning, and metallurg 2. At different pH values, chromate ions exist in ionic forms such as HCrO4−, CrO42−, Cr2O72−, and HCr2O7−3. The toxicity of chromium depends on its oxidation states, which vary from + 6 to − 24. Chromium mainly exists in water in two valences: hexavalent chromium and trivalent chromium. Chromium(VI) is more toxic than chromium(III) and is associated with the risk of cancer and kidney damage due to its high oxidation potential and easily penetrates biological membranes. Compared to Cr(VI), Cr(III) is almost non-toxic5. It is found in vegetables, yeast, meat, etc., and is beneficial for human health. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set a maximum permissible limit of chromium (VI) of less than 50 μg/L in drinking water. Therefore, it is important to remove Cr(VI) from wastewater6. Many techniques have been used to remove Cr(VI) from the environment or reduce it to Cr(III)for industrial wastewater treatment7,8. Various methods such as adsorption, coagulation, chemical precipitation, precipitation, ultrafiltration, air stripping, ion exchange, flocculation, and biological treatment were evaluated for their efficiency and limitations in wastewater treatment. These methods result in the transformation of pollutant molecules into solids or sludge, producing secondary pollutants. These techniques can remove ions or other useful molecules from water9. These methods require inorganic and organic additives and sophisticated equipment and instrumentation, which significantly hinders their practical use. photo reduction using UV light by semiconductors is one of the better methods for removing chromium (VI) from wastewater.

The photocatalytic reduction process can overcome the Existing restrictions and be widely used as an efficient, cost-effective, and sustainable technology10. Since light-activated heterogeneous photocatalysts are used for both point-of-use and large-scale water treatment applications, they have high removal capabilities for chromium (VI) pollutants from water and wastewater11. Among semiconductors, zinc oxide has attracted much attention for heavy metal removal. ZnO is a unique n-type semiconductor with a band gap of about 3.37 eV12 that exhibits good piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties. Low toxicity, high specific surface, cheap price, recyclability, different manufacturing methods, and high optical chemical stability are some other remarkable features of ZnO13. However, using ZnO during Cr(VI) reduction still faces limitations such as solubility below pH 3, poor dispersion and fast photoinduced electron–hole recombination, and narrow photoresponse range. Therefore, the photocatalytic activity of ZnO should be enhanced to reduce heavy metals14. To enhance the charge separation in ZnO, coupled semiconductors with different redox energy levels can increase the charge carrier lifetime, increase the efficiency of surface charge transfer to the photocatalyst substrate, and improve the chemical and optical properties. Usually, binary or ternary mixed metal oxides are used instead of single ZnO compounds to remove contaminants. Among metals, CuO is a perfect choice for modifying photocatalysts. Copper is cheaper than other noble metals (gold, platinum, and silver)15. Copper oxide is a p-type semiconductor with a small band gap of about 1.2–1.7 eV16 its non-toxicity and electrical properties have made it a highly efficient catalyst for ZnO17. Also, CuO can separate electron–hole pairs faster and in the visible light region. The better activity of ZnO/CuO nanocomposite is due to the favorable band edge positions of ZnO and CuO, the recombination of charge carriers is maintained and the charge carriers can be transferred to the semiconductor surface. Then the charge carriers participate in redox reactions. As a result, the photocatalytic activity of ZnO/CuO nanocomposite is better than that of ZnO18. Also, to shift the absorption edge to the visible region, zinc oxide has been doped with carbon materials such as g-C3N4, carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide, and carbon nanofibers19,20. Graphene oxide is a two-dimensional material that forms a single layer with a hexagonal crystal structure. Its planes contain oxygen groups, which allow it to interact better with materials. Graphene oxide can be covalently bonded to polymers or semiconductor materials21. Due to its high conductivity, chemical durability, and specific surface area, GO is a preferred choice for improving the photocatalytic activity of ZnO22. So far, various binary and ternary composites of zinc oxide have been synthesized for the degradation of organic and inorganic pollutants in wastewater such as Ag/ZnO23, Pd-ZnO/CeO224, TiO2/CdS/ZnS25, ZnO/SnO226, ZnO/CeO227, Pd precipitated ZnO/CuO28. Some of these composites have been used exclusively for the reduction of chromium from wastewater, for example, Liu et al. proposed ZnO-RGO for the reduction of Cr(VI) with an efficiency of 96% in 250 min under UV lamp irradiation, and the reduction of Cr(VI) with ZnO/graphene in 240 min under visible lamp irradiation29. Yang et al. synthesized BiO/ZnO/RGO which can reduce Cr(VI) with an efficiency of 92% in 180 min30. Song et al. proposed ZnO/AgVO3 or Cr(VI) reduction with an efficiency of 97% in 120 min31. Islam et al. synthesized a Cu/ZnO structure for the reduction. chromium (VI) reduction was carried out with an efficiency of 98% in 120 min under UV lamp irradiation32. Zhong et al. reduced Cr(VI) with an efficiency of 90% in 98 min under visible lamp irradiation by g-C3N4/ZnO33. According to the above reports, ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite was synthesized by hydrothermal method. The main aim of this work is to explore the synthesis of ZnO-based nanomaterials that exhibit unique properties after hybridization with other metal oxides. This property leads to the enhancement of the photocatalytic activity of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite due to the formation of a heterogeneous p–n junction. Then, we evaluated the photocatalytic reduction efficiency of ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposites under visible light. No significant change was observed at the concentration of Cr6+ (0.01 g/L) with pure zinc oxide, indicating that Cr6+ is very stable under visible light with ZnO. In the case of ZnO/CuO, the reduction rate reached 62.3%. However, 97.5% photocatalytic reduction was observed in the presence of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite. Therefore, we propose a ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite to achieve better photocatalytic activity, that reduces chromium under visible light in a shorter time and with higher efficiency than the above composites. This is the first report for the photocatalytic reduction of chromium (VI) under visible light irradiation using ZnO/GO/CuO photocatalyst.

Experimental methods

Materials

Zinc Oxide (ZnO, 99.0%), Graphene oxide (GO,325 mesh), Copper sulfate (CuSO4·5H2O, 99.0%), Ammonia solution (NH3·H2O, 32.0%), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%), Ethanol (C2H5OH, 99.9%), 1,5-diphenylcarbazide (C13H14N4O, 98.0%), Potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7, 99.9%), Acetone (C3H6O, 99.0%), Citric acid (C6H8O7, 99.5%), Sodium oxalate (Na2C2O4, 99.0%), EDTA (C10H12N2O8, 99%), Tert-butanol (C₄H₁₀O, 99.0%), Hydroquinone (C6H6O2, 99.5%), concentrated Sulphuric acid (conc. H2SO4, 98%), concentrated Hydrochloric acid (conc. HCl, 37%) were purchased from Merck Company. Deionized water was used without any purification.

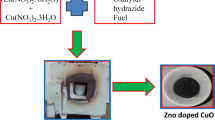

Preparation of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite

The hydrothermal method was used to prepare the ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite. At first, an aqueous GO solution was prepared by adding 0.05 gr of graphene oxide to 10 ml of deionized distilled water using an ultrasonic bath. Then, 0.5 ml of prepared graphene oxide solution was added to 20 ml of deionized distilled water and placed on the heater stirrer. After that, ZnO (0.2 gr) and CuSO4·5H2O (0.1 gr) were added and stirred for 240 min until a gray suspension solution was obtained. Then, 1 ml of NH3·H2O solution was slowly added drop by drop to the above suspension and stirred continued for 10 min. 0.5 ml of NaOH solution with a concentration of 0.1 g/ml was added to the above suspension and stirring continued for 5 min. When adding the ammonia and sodium hydroxide solution, we measure the pH of the solution using a pH meter to ensure that the pH is alkaline and around 8. The above mixture was transferred to a hydrothermal autoclave and heated in an oven for 5 h at 140 °C. The obtained product was filtered and washed with deionized water and ethanol until the pH of the solution reached 7. The obtained product was placed in an electric furnace at 450 °C for 4 h to be dried and calcined18,34. The Schematic of the photocatalyst preparation is shown in Fig. 1.

Instrumentation

The crystal structure of the synthesized sample by X-ray diffractometer (XRD), PHILIPS company, machine model: PW1730, country of manufacture: Netherlands, step size = 0.05 degree, Time per Step = 1 s, the wavelength of copper X-ray lamp = 1.54056 angstroms, voltage = 40 kV current = 30 mA; was recorded. The chemical composition of the sample synthesized by the device (FTIR), manufacturer: Thermo, Device model: AVATAR, country of manufacture: USA, reviewed. Morphology of the synthesized sample with scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), Manufacturer Company: TESCAN, model: MIRA III, country of manufacture: Czech Republic, registered. Absorption of the synthesized sample by UV–Vis spectrometer (model: UItrospec 3100 pro) was tested. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of the sample synthesized with the device (UV–Vis DRS) was measured in the range of 250–800 nm using a spectrophotometer (model: S-4100 made by SCINCO South Korea) with KBr as a reference. The BET-specific surface area measurement analysis was done to check the specific surface area and porosity of the nanofocal catalyst with the model: BELSORP Mini II made in Japan. EDAX or EDS analysis (X-ray Energy Diffraction Spectroscopy) was performed to determine the percentage of elements in the nano focal catalyst sample with the EDS SAMX device made in France.

Measurement of photocatalytic activity

The activity of the synthesized materials was investigated by the designed photoreactor, which consists of an LED metal halide lamp (400 W, 34,000 Lm, wavelength 390–750 nm) in the visible light region. To eliminate the ultraviolet radiation of the lamp, which is very small compared to the visible radiation of the lamp, we used transparent polycarbonate sheets. For the experiments, 0.1 gr of photocatalyst and 100 ml of chromium (VI) with different concentrations were poured into a double-walled Pyrex cell. Before light irradiation, the pollutant solution and photocatalyst were stirred for 30 min in the dark to achieve adsorption and desorption equilibrium35. To determine the amount of Cr(VI) reduction, 2 ml of the centrifuged solution was poured into the test tube. Then, 0.5 ml of 10% H2SO4 and 0.5 ml of 1, 5-diphenylcarbazide solutions were added to obtain a purple-colored complex of Cr(VI)36. Normally, in UV–Vis spectrophotometry, the ƛ Max value of 540 nm is assigned to the Cr(VI) peak. In this experiment, the purple complex peak of Cr(VI) was observed at 543 nm. The removal percentage can be calculated using Eq. (1).

Here, C0 is the concentration at time 0 min, Ct is the concentration at time t min, and \(\eta\) is the Cr(VI) reduction efficiency37.

Results and discussion

UV–Vis-DRS analysis

The band gap of ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite were determined by measuring the light absorption of the catalyst in the visible light region and analyzing the spectrum obtained from UV-DRS is shown in Fig. 2. Tauc theory was used to calculate the bandgap energy, which was presented in the 1970s to calculate the bandgap of semiconductors from the spectrophotometric spectrum38. Tauc’s idea is that the energy-dependent absorption coefficient can be expressed by the following Eq. (2):

If a linear relationship is acquired and the graph intersects the X line, it will be equal to the bandgap energy. In this equation, (α) is the absorption coefficient, \(\gamma\) is the power constant equivalent to Tauc, which is equal to 0.5 for the indirect bandgap and 2 for the direct bandgap. The (h) is Planck’s constant, (ν) is the radiation frequency and (Eg) is the band gap energy39. The calculated band gap of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite is about 2.48 eV. The result shows that ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite as an efficient semiconductor with a better visible light response and a smaller band edge than ZnO (3.2 eV) and ZnO/CuO (2.65 eV) can be effectively used to reduce metal pollutants.

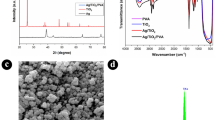

XRD

To confirm the preparation of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite, the XRD spectrum of the nanocomposite is shown in Fig. 3. The peaks at 31.7°, 34.4°, 36.4°, 47.6°, 56.7°, 62.9°, 66.4°, and 67.9° are related to the corresponding planes (100), (102), (110), (103), (112), (202) of zinc oxide nanoparticles, respectively (JCPDS data card no 48-1548). The peaks at 35.6°, 38.8°, 48.8°, and 61.5° represent CuO nanoparticles for the corresponding planes (002), (111), (022), (202), (220), and (222), respectively (JCPDS data card no 05-661). For graphene oxide, the peak appeared at 11.3° (JCPDS data card no 00-041-1487). The XRD analysis was performed to determine the structural properties of the synthesized nanomaterials. In the case of CuO nanoparticles, the crystal planes confirm the monoclinic structure, and for ZnO nanoparticles, the observed peaks confirm the hexagonal structure. The presence of the GO peak in the XRD pattern confirms the existence of a ZnO/GO/CuO three-phase nanocomposite without impurities.

To calculate the structural and microstructural parameters of the desired samples, we use the Rietveld refinement method. According to the theory of this procedure, the XRD patterns can be simulated using the initial structure parameters as the following relation40:

where, Yci, Sp, Fk, f, Pk, Lk, and Sa ith calculate intensity, the scale factor of the pth phase, structure factor, the mathematical peak shape, preferred orientation parameter, Lorentz polarization, and preferred orientation coefficients, respectively. There are different mathematical peak shape functions to characterize the observed profiles. The pseudo-Voigt-Thomson-Cox-Hasting (TCH) function is one of the best functions for evaluating the microstructural parameters, which can be expressed as follows:

where, L and G are the Lorentzian and Gaussian peak shape functions, and n is expressed as:

where HL and HG are the peak widths of Lorentzian and Gaussian profiles, respectively. The location of atoms in the lattice, the space group, and the initial lattice constants of different phases of the material are taken as initial parameters in the Rietveld method to simulate the entire X-ray diffraction patterns by relation (3). Then, the observed and simulated patterns are compared with each other. The structural and microstructural parameters are refined separately until the best fit is obtained. In this work, the new version of FullProf Suite software (version December 2024, Available from: http://www.ill.eu/sites/fullprof) was used to determine the crystallite size, lattice strain, and lattice parameters. Also, the dislocation density (ρ) can be estimated using the Williamson-Smallman equation:

where b is the burgers vector, and for the hexagonal structure \(b=\sqrt{ {a}^{2}+{c}^{2}}\). a and c are lattice constants reported in Table 1.

According to the values obtained from Table 1, the addition of CuO and Go to ZnO causes a decrease in crystallite size. This decrease is due to the disorder in the lattice structure and the creation of more grain boundaries. Since the ionic radius of Cu2+ is different from that of Zn2+, the substitution of Cu ions with Zn ions can cause changes in the lattice parameters and introduce strain into the ZnO crystal structure. GO is usually not directly substituted into the ZnO crystal lattice41, but it can affect the lattice parameters by introducing structural defects and strains. These effects are usually observed as minor changes in the lattice parameters. By adding CuO and GO as impurities to the ZnO lattice, the density of lattice defects (dislocation density) increases, which can lead to an increase in the microstrain of the ZnO lattice18,28,42.

FTIR

Figure 4 shows the FTIR spectra of ZnO, CuO, GO, and ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite. The presence of O–H bonds between 3600 and 3500 cm−1 indicates minimum moisture. Analysis of ZnO using FTIR shows peaks at 810 cm−1 and 482 cm−1 which are related to Zn–O stretching vibration. In the FTIR spectrum of CuO, peaks at 775 cm−1 and 744 cm−1 indicate Zn–O and Cu–O stretching vibration. In the FTIR spectrum of GO the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups such as hydroxyl (O–H), carbonyl (C=O), and epoxy (C–O–C) groups is revealed. O–H stretching vibrations are usually observed in the range of 3500–3200 cm−1, C=O stretching around 1600–1750 cm−1 and C–O–C stretching between 1250 and 1050 cm−1. The FTIR spectrum of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposites also shows the presence of metal–oxygen vibrations in the range of 500–600 cm−1. The results are presented in Table 2 and show that the surface modification was successfully performed.

SEM

The morphology and structure of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite was investigated by field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM). Figure 5 shows the SEM images of the nanocomposite. It is observed that the synthesized nanocomposites are formed as nanoparticles. By creating nucleation centers, the volume of clusters and the size of the synthesized structure increase during the progress of hydrothermal synthesis. The obtained particle size distribution histogram shows that the particle size distribution follows a log–normal function and most particles are 30–60 nm (Fig. 6).

EDS—Map

Figure 7a,b shows the MAP analysis and EDS spectra of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite. The EDS analysis showed peaks of oxygen, zinc, copper, and carbon elements that appeared specifically in the energy range of 0–10 keV. According to these spectra, no characteristic peaks of other impurities were observed, indicating the purity of the synthesized nanocomposite. The presence of copper, zinc, oxygen, and carbon elements with atomic percentages of 17.46, 18.25, 34.54, and 1.04 were observed. According to Fig. 7b, the dispersion of elements is uniform and we do not encounter the accumulation of a specific element in one region of the composite.

BET analysis

The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherm and pore size distribution curve of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite is shown in Fig. 8a,b. The analysis was performed under a standard vapor pressure of 90.50 kPa and the adsorption surface area was 0.164 nm. The data obtained from the nitrogen gas adsorption and desorption plots are presented in Table 3. By studying other articles and research43,44,45,46,47,48, we extracted the BET analysis for ZnO and ZnO/CuO and added them to the table. The specific surface area of ZnO is 16.79 m2/g, which increases with CuO loading (32.5 m2/g) and reaches 65.32 m2/g with GO. The higher specific surface area of ZnO/GO/CuO compared to ZnO and ZnO/CuO indicates its highly porous structure and suitability for photocatalytic applications. The hole volume and hole diameter for ZnO and CuO/ZnO are lower than those for ZnO/GO/CuO. The larger hole volume in ZnO/GO/CuO can increase its reactivity and adsorption capacity. The average hole diameter of ZnO/GO/CuO is 26.89 nm, which provides information to determine its pore type, which in this study indicates mesoporous (1.5–100 nm).

Influence of pH on photocatalytic activity

The pH is one of the most effective parameters in photocatalytic processes. The reason for this effect is the existence of different forms of photocatalysts and pollutants at different pH values. As Wu et al. reported the dominant types of Cr at different pH values are shown in Fig. 9a,b. Normally, chromium (VI) species exist as chromate (CrO42−), dichromate (Cr2O72−), hydrogen chromate (HCrO4−), dihydrogen chromate (chromic acid, H2CrO4), hydrogen dichromate (HCr2O7−), trichromats (Cr3O102−) and tetrachromate (Cr4O132−), where the form of species depends on the pH solution49. The three ions (HCr2O7−, Cr3O102−, and Cr4O132−) have been observed only in solutions with pHs < 0. At low pHs, Cr(VI) exists as HCrO4− mainly, while CrO42− occurs at pH > 6.5. The photocatalytic reduction of Cr6+ ions to Cr3+ ions is presented depending on pH through the following equations:

At neutral condition:

At acidic conditions:

At the alkaline condition:

The pHpzc of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite is 9.2. Hence, oxyanions of Cr(VI) can be readily absorbed on the ZnO/GO/CuO surface below the pHpzc since the ZnO/GO/CuO surface becomes positively charged. Moreover, the thermodynamic driving force between the redox potential of Cr(VI)/Cr(III) and the conduction band of photocatalyst became narrower with higher pH values as well as less photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) could be recorded. The ZnO/GO/CuO surface becomes negatively charged under alkaline conditions which edges the conversion of Cr2O72− oxyanions to CrO42− ion as predominant species and lessens the reduction of Cr(VI). Again, Cr(OH)3 can be deposited on the photocatalyst surface to decrease its photocatalytic activity at a higher pH. A contaminant solution of chromium was prepared with a specific concentration to investigate the effect of pH. Then, using hydrochloric acid solution (2 M) and sodium hydroxide solution (2 M), the pH was adjusted in the range of 3 to 10. At each of the adjusted pHs, a certain amount of ZnO/GO/CuO was added to the contaminant solution and the reduction rate of hexavalent chromium was measured. According to the results, the best photocatalytic performance is at pH 5, and the photocatalytic activity is severely reduced at alkaline pHs.

Influence of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite dosage on photocatalytic activity

Before investigating the effect of nanocatalyst dosage on chromium reduction, the nanocatalyst was synthesized with different amounts of raw materials. Each of these syntheses was evaluated for chromium reduction. Finally, the best ratio of starting materials for synthesis was selected. The results obtained are presented in the Supplementary Information file (see S1). Then, the reduction rate of Cr(VI) was investigated under the effect of changing different doses (0.01–0.2 gr) of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite, and the results can be seen in Fig. 10. In summary, it was observed that the reduction of chromium (VI) with the dose of 0.01–0.05 gr was up to 99% after 120 min. While a 99% reduction was recorded with doses of 0.1 gr and 0.2 gr of photocatalyst in 10 min under the same conditions. Therefore, the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) increased rapidly with increasing nanophotocatalyst dosage from 0.05 to 0.1 gr. With an increase in the nano photocatalyst dose from 0.1 to 0.2 g, no significant difference was shown in the amount of chromium reduction.

Influence of Cr(VI) concentration on photocatalytic activity

The successful application of this photocatalytic system depends on the determination of the relationship between the reduction and the initial concentration of Cr (VI). The relationship between the amount of reduction and different initial concentrations of Cr (VI) in the same operating conditions is different. Figure 11a shows the influence of Cr (VI) concentration on photocatalytic activity. The speed of photocatalytic reduction of Cr decreased with increasing pollutant concentration from 0.03 to 40 ppm. At low concentrations, the number of active sites on the catalyst is not limited and the reduction of hexavalent chromium to trivalent chromium occurs in a shorter time. As the concentration of Cr increases, the amount of adsorbed Cr would be increased on the surface of the catalyst. Therefore, the amount of reducing species (electrons) required to convert hexavalent chromium to trivalent chromium increases. On the other hand, the formation of reducing species on the photocatalyst surface always remains constant for the irradiation intensity, catalyst amount, pH and irradiation time. As a result, the amount of reducing species available is not sufficient to convert hexavalent chromium to trivalent chromium at higher concentrations. So, with increasing pollutant concentration, the rate of substitution of hexavalent chromium to trivalent chromium decreases. The increase in the initial concentration of the pollutant may lead to the production of intermediates which are likely to be adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst. Slow diffusion of intermediates onto the catalyst may cause surface passivation, resulting in reduced chromium reduction. Most academic studies on photocatalysts have been conducted in a simple matrix environment consisting of distilled water and a certain concentration of the pollutant. Investigating the simultaneous degradation of multiple pollutants in photocatalytic work is very important due to the complex nature of industrial wastewater, which often contains a mixture of different organic pollutants. The presence of multiple pollutants can affect the photocatalytic process, as organic impurities can act as radical scavengers and negatively affect the charge recombination process and consequently the overall efficiency. For this reason, we investigated the reduction of hexavalent chromium in the presence of two pollutant dyes (methylene blue and crystal violet) and a pharmaceutical pollutant (phenazopyridine) to ensure the correct performance ZnO/GO/CuO in complex wastewater matrices. In Fig. 11b, the effect of photoreduction and simultaneous photodegradation is investigated. A solution containing phenazopyridine, methylene blue, crystal violet, and chromium (VI) was prepared. It was exposed to visible light for 30 min. The ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite was able to reduce chromium (100%), methylene blue (81.8%), crystal violet (74.3%), and phenazopyridine (69.6%). The results (Table 4) show that ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite can perform chromium reduction in environments containing multiple contaminants and the presence of a complex matrix did not have a negative effect on its photocatalytic activity.

Reusability of photocatalyst

Figure 12 shows the reusability of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite for the reduction of Cr(VI). Any photocatalyst may be deactivated after a period of photocatalytic reaction. Substances that are adsorbed on the photocatalyst surface, intermediates, and photocatalytic reaction products can cause this problem. As mentioned earlier, after the light hits the photocatalyst, electron–hole pairs are generated and migrate to the catalyst surface. These charge carriers on the semiconductor surface cause oxidation and reduction reactions. However, if the charge carriers on the surface are not used in oxidation and reduction reactions, irreversible chemical changes occur in the surface layer of the semiconductor. And in the future, we will see the recombination of cargo carriers. It is even possible that as soon as light radiation occurs, defective sites are produced both on the surface and in the bulk of the catalyst. Changes in color are usually a good parameter to measure the progress of corrosion due to the reduction of photocatalytic activity. In this research, we used the first method to regenerate the photocatalyst. According to Fig. 12, the synthesized photocatalyst can be collected and reused up to 5 times.

Photocatalytic studies

According to Fig. 13, the photocatalytic reduction efficiency of the ZnO and as-prepared ZnO/CuO and ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite was evaluated under visible light. No significant changes in Cr6+ concentration (0.01 g/L) were detected with pure ZnO, indicating that the Cr6+ was highly stable under visible light with ZnO. In the case of ZnO/CuO, the reduction rate reached 62.3%. However, the 97.5% photocatalytic reduction percentage was observed in the presence of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite, because the reduction process by nanocomposite requires high visible light utilization efficiency, charge separation enhancement, and reduces the recombination rate. This result proves that the ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite exhibited an effective photocatalyst for the reduction of Cr6+. Also, these results are comparably good with nanocomposites such as ZnO–RGO31, ZnO/Graphene31, BiO/ZnO/RGO32, ZnO50, ZnO/AgVO333, Cu modified ZnO in the presence of EDTA18, g-C3N4/ZnO34 and the results are shown in Table 5.

Comparing the performance of different photocatalysts in photocatalytic reduction Cr(VI)

A comparison of the performance of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite with other photocatalysts reported in previous studies was carried out for the photocatalytic removal of hexavalent chromium. Table 5 shows the comparison results of different photocatalysts in chromium reduction. According to the information about the photocatalytic activity and different operating conditions shown, the ZnO/GO/CuO nanophotocatalyst represents a better performance in chromium reduction. It is hexavalent compared to other presented photocatalysts.

Scavengers experiments

The knowledge of the quantity of the radicals generated under given circumstances is crucial for the elucidation of the mechanism of the reduction process as well as for the assessment of the photocatalytic activity. Direct detection of these active species is rather difficult, due to their extremely high reactivity and short lifetime (OH·: 10−10 s; O2·: 51 s)51. Hence, radical scavenger compounds are usually utilized for their measurement. The scavenger can be used in itself by measuring the concentration of the initial compound or the intermediates formed in the reaction of the scavenger and the radical, applying various analytical methods (UV/Vis, emission or ESR spectroscopy, chromatography or electrochemistry methods)52. The most common method of using radical scavengers is competition-based experiments. In these studies, the effect of the scavenger on the reduction of a model compound is considered. A decrease in the amount of photocatalytic reduction indicates that the radical formed plays an important role in the photocatalytic reaction. Different scavengers are used to determine the contribution of reactive species to the photocatalytic reduction as shown in Table 6. In this work, tert-butyl alcohol, hydroquinone, sodium oxalate, acetone, and EDTA were used to determine the contribution of reactive species to the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) with ZnO/GO/CuO. The obtained results from the effect of different scavengers on the photocatalytic reduction of chromium are shown in Fig. 14. Also, to investigate the effect of sunlight on reduction, an experiment using photocatalyst and solution containing chromium was carried out in the dark for 240 min. At these conditions, no reduction occurred. Another test was performed without photocatalyst, using a solution containing chromium, exposed to light source radiation for 240 min. There was no reduction in this situation either. Hence, it is concluded that both photocatalyst and sunlight are necessary for the reduction of Cr(VI). In the following, the role of each used scavenger is investigated in detail.

Hydroxyl radical scavenger: Tert-butanol

Tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) and similar alcohols are often used as scavengers for hydroxyl radicals. This can be explained by the strong tendency of hydroxyl radicals to abstract a hydrogen atom whenever possible (due to the electrophilic nature of OH·), forming free radicals and water molecules53,54. Tert-butyl alcohol reacts with adsorbed hydroxyl radicals on the surface of photocatalyst (OH· ads). If OH· ads are effective for photoreduction, the reduction rate should be decreased by the addition of scavenger C₄H₁₀O. In this research, the addition of C₄H₁₀O did influence the photoreduction of Cr(VI). The result revealed that the addition of C₄H₁₀O inhibited the photoreduction of Cr(VI) indicating the role of OH· ads on the surface of the photocatalyst. The C₄H₁₀O could scavenge all the produced hydroxyl radicals (surface and bulk) in the system. If the hydroxyl radicals play a role in the photoreduction, the reaction rate is reduced. As shown in Scheme 1, hydroxyl radicals indicated a major role in the reduction of Cr(VI), and without them, no reaction occur55.

In the presence of alcohol, hydroxyl radicals (according to equation OH· + H+ → H2O) are converted into water molecules and do not participate in the photocatalytic reaction.

Electron scavengers: Acetone

Acetone can act as an electron scavenger by undergoing a reduction reaction, which involves the acceptance of electrons from other molecules. Acetone has a carbonyl group (C=O) that contains a polarized carbon–oxygen double bond. This polarized bond can act as an electron acceptor and is susceptible to reduction. When acetone encounters a molecule with excess electrons, such as a free radical or an anion, the carbonyl group can accept one or more electrons from that molecule. The reduction of the carbonyl group leads to the formation of a secondary alcohol group (C–OH) and the production of an acetone radical intermediate. The photo reduction in the presence of Acetone is revealed in Scheme 2:

The acetone radical is free and can scavenge additional electrons from other molecules, leading to a chain reaction of electron scavenging. Overall, the mechanism of electron scavenging by acetone involves the reduction of the carbonyl group to a secondary alcohol group, followed by the generation of a free radical intermediate that can scavenge additional electrons. In the presence of acetone, a chromium reduction reaction and 99% reduction occur. This indicates electron–hole formation during photocatalytic activity and confirms that the dominant mechanism in this reaction is not through the formation of electrons.

Superoxide radical scavenger: Hydroquinone

Hydroquinone, also known as benzene-1,4-diol or quinol, is an aromatic organic compound that is a type of phenolic derivative of benzene. Hydroquinone has two hydroxyl groups bonded to a benzene ring in a para position. The reactivity of hydroquinone’s hydroxyl groups resembles that other phenols are weakly acidic. Hydroquinone undergoes oxidation under mild conditions to give benzoquinone. To study the role of superoxide radical anion, O2−·, Hydroquinone was used as an O2−· scavenger. The photoreduction in the presence of Hydroquinone is as follows (Scheme 3):

For O2·− detection, a solution of HQ was used. The photocatalytic materials along with Cr were dissolved in the HQ solution and were irradiated with visible light under continuous stirring conditions. The generated O2·− are captured by HQ, and if superoxide is the active ROS, then the rate of pollutant reduction decreases. Experiments showed that the photoreduction of Cr(VI) has occurred in the presence of Hydroquinone, indicating that O2−· does not have a special role in Cr(VI) reduction56.

Hole scavengers: Sodium oxalate, EDTA

Many researchers have used oxalate as a hole trap in mechanistic investigations. The pH has an important role during heterogeneous photocatalysis since it affects the surface of the photocatalyst. The hole-scavenging effect using oxalate was monitored at the optimum pH of 5. The photoreduction in the presence of oxalate is represented in Scheme 4:

The effect of adding EDTA on the photoreduction efficiency of chromium (VI) has been explored in this research. In the presence of a suitable hole (h +), the number of available electrons for the photocatalytic reduction of the model component should increase. The mechanism of the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) in the presence of EDTA is a complicated reaction. The mechanism was based on three aspects, (1) the small amount of Cu can act as electron trapping sites which slowly reduce the electron–hole recombination; (2) the one-step reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) by the photo–generated electrons (e −); (3) water was oxidized by valence band holes to produce hydroxyl radicals. Therefore, a sacrificial electron donor (EDTA) can be oxidized by valence band holes and hydroxyl radicals. By changing the pH of the solution to basic, it seems that EDTA loses 1 to 4 H+ ions and, its structure becomes negatively charged, and on the other side, the surface charge of the photocatalyst becomes positive, which competes with Cr(VI) which resulted in adsorption of Cr(VI)on the surface of the photocatalyst and causes the formation of superoxide radicals by eliminating the hole. The reduction of Cr by eCB is also possible. Therefore, the efficiency of Cr reduction increases. Over time, the ability of EDTA to adsorb on the photocatalyst surface and cover the holes decreases. As a result, the rate of electron–hole recombination increases, and the efficiency of Cr reduction decreases. The results show that from 20 min, the photoreduction of Cr decreases with the addition of EDTA. The obtained results do not neglect the role of holes in the overall mechanism of photoreduction but indicate that the overall reaction mechanism does not proceed through hole formation57. The photoreduction in the presence of EDTA is shown in Scheme 5:

The mechanism of photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI)

The mechanism of photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) using ZnO, CuO, and GO involves the steps of adsorption, photoactivation, free radical generation, and electron transfer. ZnO and CuO act as the main photocatalysts, while GO as a co-agent can improve the adsorption of Cr(VI) and electron transfer. Initially, Cr(VI) ions (such as chromate or dichromate) are adsorbed on the surface of the photocatalyst. This adsorption can occur through electrostatic interactions or the formation of chemical bonds. Upon irradiation with visible light, electrons in the valence band of the photocatalyst are excited to the conduction band, and positive holes (h⁺) are created in the valence band. The excited electrons in the conduction band can react with molecular oxygen (O2) to produce superoxide radicals (O2·⁻). Also, the positive holes can react with water or hydroxide ions (OH⁻) to produce hydroxyl radicals (OH·). The electrons in the conduction band of the photocatalyst can be directly transferred to Cr(VI) ions and reduced to Cr(III). Also, superoxide and hydroxyl radicals can participate in this reduction process. According to the results obtained from the scavengers, it can be said that (OH·) radicals play the most role in the reduction of Cr(VI) by the ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite. A Schematic photoreduction mechanism of Cr(VI) by ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite is shown in Fig. 15.

Conclusion

In this study, the application of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite for the reduction of chromium (VI) under visible light in the presence of citric acid was investigated. By attaching CuO and ZnO nanoparticles to the GO framework, not only the e− and h+ separation was increased, but also the bandgap of ZnO was reduced, causing its photocatalytic activity to shift from the ultraviolet to the visible light range. The presence of GO also accelerated the efficient electron transfer and prevented the recombination (electron–hole). The ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite showed a 97% reduction of hexavalent chromium (10 ppm) within 40 min at pH 5, which was more efficient than the ZnO/CuO (65%) and ZnO (7%) starting materials. Furthermore, this nanocomposite degraded methylene blue, crystal violet, and phenazopyridine with degradation (%) of 81.8%, 74.3%, and 69.9%, respectively, within 30 min. Tert-butyl alcohol, hydroquinone, sodium oxalate, acetone, and EDTA were investigated as adsorbents in the reduction of chromium (VI) to chromium (III). In the presence of tert-butyl alcohol, a 74% reduction of chromium was observed, while with the other compounds, the reduction rate of chromium was 99%. Finally, the result shows that ZnO/GO/CuO as an efficient semiconductor with better visible light response and smaller band edge (2.48 eV) than ZnO (3.2 eV) and ZnO/CuO (2.65 eV) can be effectively used for the reduction of metal contaminants. The ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite showed excellent stability over six cycles, highlighting its potential for practical applications.

Data availability

Data is available on request. If someone has any question can contact the corresponding authors.

References

Cao, J. et al. Green synthesis of amphipathic graphene aerogel constructed by using the framework of polymer-surfactant complex for water remediation. J. Appl. Surf. Sci. 444, 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.02.282 (2018).

Jiang, B. et al. The reduction of Cr (VI) to Cr (III) mediated by environmentally relevant carboxylic acids: State-of-the-art and perspectives. J. Hazard. Mater. 365, 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.10.070 (2019).

Kangralkar, M. V., Manjanna, J., Momin, N. & Rane, K. S. Photocatalytic degradation of hexavalent chromium and different staining dyes by ZnO in aqueous medium under UV light. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 16, 100508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100508 (2021).

Ertani, A., Mietto, A., Borin, M. & Nardi, S. Chromium in agricultural soils and crops: A review. Rev. Wat. Air Soil Poll. 228, 190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-017-3356-y (2017).

Wang, N., Zhang, F., Mei, Q., Wu, R. & Wang, W. Photocatalytic TiO2/rGO/CuO composite for wastewater treatment of Cr(VI) under visible light. Water Air Soil Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-020-04609-8 (2020).

Li, J., Liu, Z. & Zhu, Z. Enhanced photocatalytic activity in ZnFe2O4–ZnO–Ag3PO4 hollow nanospheres through the cascadal electron transfer with magnetical separation. J. Alloys Compd. 636, 229–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.02.176 (2015).

Habibi, S., Nematollahzadeh, A. & Mousavi, S. A. Nano-scale modification of polysulfone membrane matrix and the surface for the separation of chromium ions from water. J. Chem. Eng. 267, 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2015.01.047 (2015).

Lu, P. et al. Layered double hydroxide/graphene oxide hybrid incorporated polysulfone substrate for thin-film nanocomposite forward osmosis membranes. RSC Adv. 6(61), 56599–56609. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra10080e (2016).

He, J. et al. Hierarchical S-Scheme heterostructure of CdIn2S4@UiO-66-NH2 toward synchronously boosting photocatalytic removal of Cr(VI) and tetracycline. Inorgan. Chem. 61(49), 19961–19973. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c03240 (2022).

Acharya, R., Naik, B. & Parida, K. Cr(VI) remediation from aqueous environment through modified-TiO2-mediated photocatalytic reduction. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 9, 1448–1470. https://doi.org/10.3762/bjnano.9.137 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Unlocking the unique catalysts of CoTiO3/BiVO4@MIL-Fe (53) for improving Cr(VI) reduction and tetracycline degradation. Carbon Neutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43979-024-00092-w (2024).

Kangralkar, M. V. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of hexavalent chromium and different staining dyes by ZnO in aqueous medium under UV light. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 16, 100508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100508 (2021).

Li, J., Li, Y., Wu, H., Naraginti, S. & Wu, Y. Facile synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles by Actinidia deliciosa fruit peel extract: Bactericidal, anticancer and detoxification properties. Environ. Res. 200, 111433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111433 (2021).

Islam, J. B., Furukawa, M., Tateishi, I., Katsumata, H. & Kaneco, S. Photocatalytic reduction of hexavalent chromium with nanosized TiO2 in presence of formic acid. Chem. Eng. 3(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering3020033 (2019).

Bhanushali, S., Ghosh, P., Ganesh, A. & Cheng, W. 1D copper nanostructures: Progress. Cheng Small 11(11), 1232–1252. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201402295 (2014).

Chauhan, M. et al. Green synthesis of CuO nanomaterials and their proficient use for organic waste removal and antimicrobial application. Environ. Res. 168, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.09.024 (2019).

Janczarek, M. & Kowalska, E. On the origin of enhanced photocatalytic activity of copper-modified Titania in the oxidative reaction systems. Catalysts 7(11), 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7110317 (2017).

Kumari, V. et al. Synthesis and characterization of heterogeneous ZnO/CuO hierarchical nanostructures for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant. Adv. Powder Technol. 31(7), 2658–2668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.04.033 (2020).

Sánchez, L. A., Huayta, B. E., Ramos, P. G. & Rodriguez, J. M. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnO Nanorods/(Graphene Oxide, Reduced Graphene Oxide) for degradation of methyl orange dye. J. Phys. 2172(1), 012013. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2172/1/012013 (2022).

Jamjoum, H. A., Umar, K., Adnan, R., Razali, M. R. & Mohamad Ibrahim, M. N. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activities of graphene oxide/metal oxides nanocomposites. Rev. Front Chem. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.752276 (2021).

Kamat, P. V. Graphene-based nanoassemblies for energy conversion. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz101639v (2011).

Guo, H. et al. Enhanced catalytic performance of graphene-TiO2 nanocomposites for synergetic degradation of fluoroquinolone antibiotic in pulsed discharge plasma system. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 248, 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.01.052 (2019).

Yadav, S. et al. Ag/ZnO nano-structures synthesized by single-step solution combustion approach for the photodegradation of Cibacron Red and Triclopyr. Appl. Nanosci. 11(7), 1977–1991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-021-01943-z (2021).

Kumari, V. et al. Ultrasonically Pd functionalized, surface plasmon enhanced ZnO/CeO2 heterostructure for degradation of organic pollutants in water. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-022-02762-z (2022).

Mittal, A. et al. Highly efficient, visible active TiO2/CdS/ZnS photocatalyst, study of activity in an ultra-low energy consumption LED based photo reactor. J. Mater. Sci. Mater Electron. 30(19), 17933–17946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-019-02147-6 (2019).

Yadav, S., Kumar, N., Kumari, V., Mittal, A. & Sharma, S. Photocatalytic degradation of Triclopyr, a persistent pesticide by ZnO/SnO2 nano-composities. Mater. Today 19, 642–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.746 (2019).

Kumari, V. et al. Hydrothermally synthesized nano-carrots ZnO with CeO2 heterojunctions and their photocatalytic activity towards different organic pollutants. J. Mater Sci: Mater. Electron. 31(7), 5227–5240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-020-03083-6 (2020).

Kumari, V. et al. Surface Plasmon response of Pd deposited ZnO/CuO nanostructures with enhanced photocatalytic efficacy towards the degradation of organic pollutants. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 121, 108241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108241 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. UV-assisted photocatalytic synthesis of ZnO–reduced graphene oxide composites with enhanced photocatalytic activity in reduction of Cr(VI). J. Chem. Eng. 183, 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.12.068 (2012).

Yang, L. et al. Synthesis of rGO/BiOI/ZnO composites with efficient photocatalytic reduction of aqueous Cr(VI) under visible-light irradiation. Mater. Res. Bull. 112, 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2018.12.019 (2019).

Song, S., Wu, K., Wu, H., Guo, J. & Zhang, L. Synthesis of Z-scheme multi-shelled ZnO/AgVO3 spheres as photocatalysts for the degradation of ciprofloxacin and reduction of chromium(VI). J. Mater Sci. 55(12), 4987–5007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-04316-8 (2020).

Islam, J. B. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic reduction of toxic Cr(VI) with Cu modified ZnO nanoparticles in presence of EDTA under UV illumination. SN Appl. Sci. 1(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1282-x (2019).

Zhong, Q., Lan, H., Zhang, M., Zhu, H. & Bu, M. Preparation of heterostructure g-C3N4/ZnO nanorods for high photocatalytic activity on different pollutants (MB, RhB, Cr(VI) and eosin). Ceram. Int. 46(8), 12192–12199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.01.265 (2020).

Jäger, H. et al. A screening of results on the decay length in concentrated electrolytes. Faraday Discuss. 246, 520–539. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3fd00043e (2023).

Mei, Q. et al. TiO2/Fe2O3 heterostructures with enhanced photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) under visible light irradiation. RSC Adv. 9(39), 22764–22771. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ra03531a (2019).

Bian, Z., Tachikawa, T. & Majima, T. Superstructure of TiO2 crystalline nanoparticles yields effective conduction pathways for photogenerated charges. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3(11), 1422–1427. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz3005128 (2012).

Kumar, K. V. A., Lakshminarayana, B., Vinodkumar, T. & Subrahmanyam, Ch. Cu-ZnO for visible light induced mineralization of Bisphenol-A: Impact of Cu ion doping. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7(3), 103057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103057 (2019).

Nguyen, D. C. T., Cho, K. Y. & Oh, W.-C. Mesoporous CuO-graphene coating of mesoporous TiO2 for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of organic dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 211, 646–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2018.10.009 (2019).

Mansingh, S., Padhi, D. K. & Parida, K. M. Enhanced visible light harnessing and oxygen vacancy promoted N, S co-doped CeO2 nanoparticle: A challenging photocatalyst for Cr(VI) reduction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7(13), 2772–2781. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cy00499k (2017).

Soltanian, A., Ghasemi, M., Eftekhari, L. & Soleimanian, V. Correlation between the optical and microstructural characteristics and surface wettability transition of In2O3: Sn/ZnO nanostructured bilayer system for self-cleaning application. Phys. Scr. 98(7), 075912. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/acd9fd (2023).

Jia, L., Yuan, H., Chang, Y., Gu, M. & Zhu, J. Dynamic instability of lithiated phosphorene. RSC Adv. 10(53), 32259–32264. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra04885b (2020).

Aghdaee, S. R. & Soleimanian, V. Effect of thickness and heat treatment on the crystallite size and dislocation density of nanostructured zinc oxide thin films. J. Cryst. Growth. 312(20), 3050–3056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2010.07.024 (2010).

Zhang, Z., Kang, S. & Zhang, X. Indoor carrier phase positioning technology based on OFDM system. Sensors 21(20), 6731. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21206731 (2021).

Bazant, P., Sedlacek, T., Kuritka, I., Podlipny, D. & Holcapkova, P. Synthesis and effect of hierarchically structured Ag-ZnO hybrid on the surface antibacterial activity of a propylene-based elastomer blends. J. Mater. 11(3), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11030363 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Fabrication of concentric carbon nanotube rings and their application on regulating cell growth. ACS Omega 4(14), 16209–16216. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b02449 (2019).

Hasan, I., Shekhar, C., Bin Sharfan, I. I., Khan, R. A. & Alsalme, A. Ecofriendly green synthesis of the ZnO-Doped CuO@Alg bionanocomposite for efficient oxidative degradation of p-Nitrophenol. ACS Omega 5(49), 32011–32022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c04917 (2020).

Jung Lee, H., Bai, S.-J. & Seok Song, Y. Microfluidic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of carbon composite nanofluids. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00760-1 (2017).

Rajamohan, R., Raorane, C. J., Kim, S.-C., Ashokkumar, S. & Lee, Y. R. Novel microwave synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and appraisal of the antibacterial application. J. Micromach. 14(2), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14020456 (2023).

Unceta, N., Séby, F., Malherbe, J. & Donard, O. F. X. Chromium speciation in solid matrices and regulation: A review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 397(3), 1097–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-009-3417-1 (2010).

Shirzad Siboni, M., Samadi, M. T., Yang, J. K. & Lee, S. M. Photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) and Ni(II) in aqueous solution by synthesized nanoparticle ZnO under ultraviolet light irradiation: A kinetic study. Environ. Technol. 32(14), 1573–1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2010.543933 (2011).

Kwon, B. G., Kim, J.-O. & Kwon, J.-K. An advanced kinetic method for HO2/O2- determination by using terephthalate in the aqueous solution. Eng. Res. Dev. 17(4), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.4491/eer.2012.17.4.205 (2012).

Fernández-Castro, P., Vallejo, M., San Román, M. F. & Ortiz, I. Insight on the fundamentals of advanced oxidation processes. Role and review of the determination methods of reactive oxygen species. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 90(5), 796–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.4634 (2015).

Schneider, J. T., Firak, D. S., Ribeiro, R. R. & Peralta-Zamora, P. Use of scavenger agents in heterogeneous photocatalysis: Truths, half-truths, and misinterpretations. Phys. Chem. 22(27), 15723–15733. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cp02411b (2020).

Zelić, I. E., Povijač, K., Gilja, V., Tomašić, V. & Gomzi, Z. Photocatalytic degradation of acetamiprid in a rotating photoreactor—Determination of reactive species. Catal. Commun. 169, 106474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2022.106474 (2022).

Gao, Z., Zhang, D. & Jun, Y.-S. Does tert-butyl alcohol really terminate the oxidative activity of OH· in inorganic redox chemistry?. Sci. Technol. 55(15), 10442–10450. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c01578 (2021).

Fónagy, O., Szabó-Bárdos, E. & Horváth, O. 1,4-Benzoquinone and 1,4-hydroquinone based determination of electron and superoxide radical formed in heterogeneous photocatalytic systems. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 407, 113057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.113057 (2021).

Islam, J. B. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic reduction of toxic Cr(VI) with Cu modified ZnO nanoparticles in presence of EDTA under UV illumination. SN Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1282-x (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the supports provided by University of Shahrekord. This research has received no funding.

Funding

This study was not supported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT authorship contribution statement Seyedeh Marzeyeh Hosseini: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, writing the original draft. Saeid Asadpour: Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization. Mohsen Ghasemi: Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization. Mahboube Shirani: Review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

No human subjects were used in this study.

Consent to publish

No human studies were used in this study. Since no individual data were used, no consent form is required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseini, S.M., Asadpour, S., Ghasemi, M. et al. Efficient photocatalytic activity of ZnO/GO/CuO nanocomposite with solar light for reduction of hexavalent chromium. Sci Rep 15, 20780 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05790-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05790-8