Abstract

Red emitting materials are critical to a wide range of optoelectronic devices, such as displays, lasers, and light-emitting diodes. Ongoing research efforts are focused on enhancing their emission efficiency and improving their thermal and mechanical stability to meet the demands of advanced device applications. Accordingly, a host glass network with the composition 50P2O5-20ZnO-20Bi2O3-10BaO (PZBB) was proposed and reinforced with 1 mol% of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions to produce efficient red emission with high thermal and mechanical stability. Structural changes due to compositional variations were analyzed via X-ray diffraction (XRD), density measurements, and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. These analyses revealed a high network tightness with a very slight increase with the introduction of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions. The produced host PZBB and developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, or PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses exhibited high thermal stability and elasticity, confirming their potential for use in optoelectronic device applications. Distinctive absorption bands of Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions were detected across the 200–2500 nm spectral range. Excitation of the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, or PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses at 308 nm resulted in red emission at 619 & 639 nm, 616 & 677 nm, or 626 nm, respectively. Oscillator strength, Judd–Ofelt, and gain analyses confirm the suitability of PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ for efficient red emission applications. Gain cross section analysis reveals that PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass supports broadband and dual-ion emission, with potential energy transfer enhancing Nd³⁺-dominated red emission output, while Ce3+ (PZBBCe3+) and Nd3+ (PZBBNd3+) singly doped glasses show broad and selective gain, respectively—highlighting their suitability for tunable and narrow-linewidth red emission applications. Overall, the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, or PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses demonstrated high photoluminescence efficiency in the red region, along with excellent thermal stability and elasticity, making them promising candidates for single- and dual-wavelength optoelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Red emission materials exhibit distinct properties that make them highly valuable in a wide range of applications, including optical communication, night vision technology, laser systems, entertainment displays, and biomedical fields such as imaging, diagnosis, and therapeutic procedures1,2. The choice of luminescent host materials plays a critical role for determining the performance and further development of red-emitting systems1,2. Rare-earth (RE3+) ion-doped glass materials are recognized as one of most effective hosts for red-emitting applications3,4,5. Their broad optical transparency across a broad wavelength range and their ability to be shaped into various geometric forms make glass a versatile option for a variety of optoelectronic devices. Furthermore, these materials can be engineered to exhibit high thermal stability, essential for maintaining performance under elevated operating temperatures6,7. At high temperatures, glass materials may undergo crystallization, deleting emission efficiency by increasing scattering and absorption losses, altering dopant distribution, and raising the excitation threshold. The impact of crystallization on luminescent performance depends on the extent of crystallization, the nature of the formed crystalline phases, and the degree of control over the crystallization process. To ensure optimal red emission, the glass should retain a predominantly amorphous structure with minimal crystallization8,9. Phosphate glass has proven to be an effective host for RE3+ ions, which are essential for luminescent materials. This type of glass offers high optical transparency, low melting point, low phonon energy, and superior rare-earth ion solubility10,11. Despite these advantages, phosphate glass is relatively mechanically fragile, exhibits limited thermal stability, high hygroscopicity, and reduced chemical durability. To address these issues, it is often necessary to enhance phosphate glass with appropriate additives to improve its overall performance12,13,14. Heavy metal oxides are particularly has proven effective in strengthening its mechanical integrity and thermal stability of phosphate glass while lowering its melting temperature —an advantage that facilitates easier glass processing. These oxides also help improve the chemical durability of phosphate glass. Bi2O3 and BaO, for example, integrate well within the phosphate glass network, altering its properties beneficially15,16,17. Transition metal oxides such as ZnO play crucial roles in linking phosphate anions and preventing hydration reactions18,19, and Zn2+ ions further stabilize the network by forming strong ionic bonds with neighboring oxygen atoms19,20. Rare earth ions (RE3+) are particularly efficient as luminescent additives because of their extensive range of energy levels, which allows them to emit a wide spectrum of wavelengths with high intensity21,22. Among these, Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions are notable for their strong emission across different regions via both up-conversion or down-conversion mechanisms, either independently or through energy transfer interactions22,23,24. Ce3+ ion has a unique property: it undergoes an allowed \(\:d-f\) transition, compared to the partially forbidden \(\:f-f\) transitions of other RE3+ ions. This allowed transition gives Ce3+ ion high excitation efficiency and enhanced luminescence, making it an ideal emitter for various photonics applications25,26. The Ce3+ is among the most prevalent RE3+ ions, and its relatively abundant availability leads to a lower price compared to many other RE3+ ions27,28,29. One advantage of utilizing Ce3+ in photoluminescent media is its efficient energy transfer ability, which is attributed to its rapid fluorescence decay and the favorable overlap between its emission spectra and the absorption bands of other RE3+ ions. This synergy enhances the overall functionality of the photoluminescent systems by facilitating effective energy transfer processes26,30,31. In contrast, Nd3+ is more expensive than Ce3+ due to its growing demand across various applications. While Nd3+ is less abundant than Ce3+, it remains more affordable than several other RE3+ ions, particularly those that are even rarer28,32. Additionally, Nd3+ ion exhibits a wide range of energy levels like Er3+, but it is significantly cheaper25,31,33. So, both Ce3+ and Nd3+ are often regarded as more cost-effective compared to other RE3+ ions. Ongoing research continues to explore the photoluminescence capabilities of various RE3+ ions, especially Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions in different host media across different wavelengths. This field remains dynamic, with studies focusing on enhancing the thermal, mechanical, thermomechanical, and chemical stability of luminescent materials, alongside improving their photoluminescence efficiency34,35,36,37,38. The majority of research on energy transfer from cerium to neodymium primarily focuses on near-infrared (NIR) emission, as this is the most commonly observed outcome. In contrast, red emission resulting from this energy transfer is rare and has been reported infrequently. Meng et al.39 generated NIR emission (880–930 nm) from CaSc2O4:Ce3+,Nd3+ phosphor under blue light excitation. It was showed the emitted NIR via Nd³⁺ strongly enhanced 200-fold by Ce3+ co-doping through efficient Ce³⁺→Nd³⁺ energy transfer, enabled by Ce3+’s 4f – 5d strong absorption and rapid energy relay. Tai et al.40 demonstrated NIR quantum cutting via Ce3+→Nd3+ energy transfer in YAG: Ce3+,Nd3+, showing enhanced 1064 nm emission, with peak efficiency (160.7%) at 10 mol% Nd3+ without quenching. Ait Mellal et al.41 convert UV light to NIR emission (~ 1059 nm) via Ce³⁺→Nd³⁺ energy transfer in LaPO4:Ce3+,Nd3+ phosphors, reaching ~ 172% quantum efficiency—ideal for enhancing c-Si solar cell spectral response.

Hence, to achieve a red emission, a host glass with the composition 50P2O5−20ZnO-20Bi2O3−10BaO (PZBB) was prepared and doped with 1 mol% of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions (PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, or PZBBCe3+-Nd33+). The novelty of the current study lies in the successful generation of efficient red emission from Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions-based glass. This effectively addresses the challenges faced by other RE3+ glass-based red-emitting glasses, such as broad emission bandwidths, thermal quenching, energy transfer losses, and high cost. Additionally, it is important to highlight that the chosen Ce3+ and Nd3+ concentrations were carefully selected to overcome the photoluminescence quenching, a common issue that arises when RE3+ ions’ concentrations exceed permissible limits. A comprehensive analysis of the structural, thermal, mechanical, and optical characteristics of the synthesized PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd33+ was conducted via techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), density measurements, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), ultrasonic, and UV-Vis optical absorption spectroscopy. Additionally, the red photoluminescence of the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd33+ glasses was investigated using a 308 nm excitation wavelength.

Experimental procedures

Material Preparation and chemical analysis

A glass matrix with the chemical formula 50P2O5−20ZnO-20Bi2O3−10BaO (PZBB host glass) was synthesized by the melt-quenching technique. A 1 mol % of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions was incorporated into the produced host PZBB glass, producing a series of developed glasses PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd33+ to generate a red-light emission. High-purity raw materials (sourced from Sigma-Aldrich), including (NH4)2HPO4 (99.99%), ZnO (99.98%), (BiO)2CO3 (99.95%), BaCO3 (99.99%), CeO2 (99.99%), and Nd2O3 (99.99%), were weighed and ground in a porcelain mortar for one hour to ensure uniformity. The mixture was then melted at \(\:1200\pm\:1\) °C for two hours, followed by casting into a stainless-steel mold at \(\:330\pm\:1\) °C for 30 min of annealing. During the melting process, the molten material was shaken at 10-minute intervals to ensure consistent homogeneity prior to casting. The precise chemical composition of the resulting host PZBB and developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses were determined via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) with a Hitachi S-3400 N SEM and a Thermo EDX Peltier-cooled X-ray detector. The results of the chemical analysis are provided in Table 1, alongside the targeted synthesis values.

Materials examination

The amorphous nature of the host PZBB and the developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses was examined via X-ray diffraction (XRD). XRD patterns were recorded with a Philips diffractometer equipped with a Cu-Kα radiation source (\(\:\lambda\:=1.54056\:\text{\AA\:}\)). To determine the density of the host PZBB and the developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, Archimedes’ principle was applied (Eq. 1)42,43,44. Each glass sample was weighed in both air and toluene using a high-precision digital balance (± 0.001 g accuracy), with five measurements taken for each sample. The density was calculated from the average of these weight measurements. To assess the impact of the Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions on the structural properties of the proposed PZBB host glass, the measured densities were used to calculate molar volume (\(\:{V}_{m}\)), mean phosphor-phosphor separation (\(\:{d}_{P-P}\)), oxygen packing density (OPD), and total ionic packing density (\(\:{V}_{t}\)) values via Eqs. 2, 3, 4, and 542,43,44.

where \(\:{W}_{a}\) and \(\:{W}_{t}\) represent the measured weights of the PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass samples in air and toluene. \(\:{\rho\:}_{t}\) is the density of toluene, \(\:M\) is the molar mass of the considered glasses, \(\:{N}_{A}\) is Avogadro’s number, \(\:{V}_{m}^{P}\) is the volume occupied by one mole of phosphor ions in the glass, \(\:n\) is the number of oxygen atoms per formula unit, \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the mole fraction, and \(\:{V}_{i}\) is the packing factor. The \(\:{V}_{m}^{P}\) and \(\:{V}_{i}\) were determined via the following formulas

where, \(\:{X}_{P}\) represents the molar fraction of P2O5, while \(\:{r}_{A}\) and \(\:{r}_{B}\) denote the ionic radii of the cation and anion, respectively, for the oxide component \(\:{A}_{b}{O}_{c}\).

A JASCO FT-IR 6200 spectrometer was utilized to record the FTIR spectra covering the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm+1 (± 2 cm⁻¹). This analysis was performed to investigate the vibrational modes of the fabricated PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd33+ glasses. Thermal behavior was analyzed via differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) with an SDT Q600 thermal analysis system, utilizing an open platinum crucible. The measurements were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and a gas flow pressure of 15 psi. The resulting DSC curves were used to estimate the glass transition temperature (\(\:{T}_{g}\)), onset crystallization temperature (\(\:{T}_{C1}\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{T}_{C2}\)), and peak crystallization temperature (\(\:{T}_{P1}\)and \(\:{T}_{P2}\)). Thermal stability (\(\:\varDelta\:T\)) of the PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses were calculated from the difference between \(\:{T}_{C2}\) and \(\:{T}_{g}\) (\(\:\varDelta\:T={T}_{C2}-{T}_{g}\))19. Ultrasonic longitudinal wave velocity (\(\:{v}_{L}\)) and shear wave velocity (\(\:{v}_{S}\)) were measured via the pulse-echo method with the SNAP, RAM-5000, RITEC system from Warwick, United States. Using the obtained values for \(\:{v}_{L}\) and \(\:{v}_{S}\), the longitudinal modulus (\(\:{C}_{11}\)), shear modulus (\(\:{C}_{44}\)), bulk modulus (\(\:B\)), Young’s modulus (\(\:Y\)), Poisson’s ratio (\(\:\sigma\:\)), microhardness (\(\:{H}_{UT}\)), acoustic impedance (\(\:{Z}_{i}\)), and Debye temperature (\(\:{O}_{D}\)) were estimated via the following Eqs45,46.

where, \(\:h\), and \(\:{K}_{B}\) are Planck’s and Boltzmann constants, respectively. \(\:{v}_{mean}\) represents the mean ultrasonic velocity and calculated by

Optical absorption spectra were measured via a Jenway 6405 UV/Vis spectrophotometer with a resolution of 2 nm. The measurements were conducted on highly-polished circular samples, each with a diameter of 2 cm and a thickness ranging from approximately 1.200 to 1.450 mm, over the spectral range of 200–1100 nm. The photoluminescence spectra of the PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses were recorded via an Edinburgh FLS1000 steady-state/transient fluorescence spectrometer. Excitation was provided by a xenon lamp at a wavelength of 308 nm.

Results and discussion

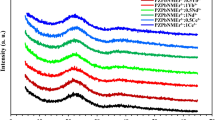

The X-ray diffraction pattern presented in Fig. 1 reveals the amorphous nature of the considered PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd33+ glasses. The broad, continuous diffraction feature observed is due to scattering from the irregular atomic arrangement within these glasses. As shown in Fig. 1, there was no significant change in the XRD patterns with the addition of Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions, indicating that the amorphous phase remained stable even with the incorporation of these ions into the host PZBB network.

Initially, as shown in Table 2, the PZBB host glass exhibited a density of 4.202 g/cm³. Introducing CeO2, Nd2O3, or CeO2/Nd2O3 resulted in a minor growth in density compared to the PZBB, as shown in Table 2. Since CeO2, Nd2O3, or CeO2/Nd2O3 were added as dopants rather than substitutes, their presence within the glass network resulted in a higher network density due to their accumulation. The developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses exhibited the same density, as listed in Table 2. Conversely, the molar volume of all developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses decreased compared to the PZBB host, as indicated in Table 2. This implies that the incorporated Ce3+ and Nd3+ diffuse into the glass network, occupying interstitial voids, which results in a reduction in interstitial distances. Additionally, the incorporation of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions caused the network constituents to move closer together, further decreasing the molar volume. This was supported by the reduction in the mean phosphor-phosphor separation, as detailed in Table 2. The decrease in molar volume and mean phosphor-phosphor separation highlights an increase in the network’s tightness. This is further supported by the changes in the oxygen packing density (OPD) and total ionic packing density (\(\:{V}_{t}\)), which refer to the tightness with which oxygen atoms are packed within the glass network and the fraction of the glass volume occupied by the constituent ions, respectively. As listed in Table 2, both OPD and \(\:{V}_{t}\) increased in the developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses compared with the host glass PZBB. This indicates a more densely packed oxygen network, stronger interatomic interactions, and less free volume within the glass, suggesting greater network rigidity. A comparison of the roles of Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions within the glass network revealed that Ce3+ ions have a greater effect on increasing the tightness of the glass network. This is due to the larger ionic radius of Ce3+, which allows it to spread more effectively inside the glass network, fill more voids, and reduce inter-distances, thereby enhancing the overall tightness of the network.

In the FTIR spectrum of the PZBB host glass shown in Fig. 2, the prominent absorption band at low-frequency centered at 460 cm−1 corresponds to the deformation modes of the \(\:{\text{P}\text{O}}_{4}^{3-}\)groups (\(\:{\text{Q}}^{0}\)), bending modes of the \(\:\text{O}=\text{P}-\text{O}\) linkages in \(\:{\text{Q}}^{1}\) units, and the stretching of \(\:\text{M}-\text{O}-\text{P}\) (where M denotes the metal ions in the current glass Zn2+, Bi3+, Ba2+)47,48,49. The band at 680 cm−1 corresponds to the symmetric stretching vibration of \(\:\text{P}-\text{O}-\text{P}\) rings (\(\:{\text{Q}}^{1}\))47,48,49. The band centered at 865 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of \(\:\text{P}-\text{O}-\text{P}\) linkages in \(\:{\text{Q}}^{1}\) units50,51. The broadband peak centered at 1035 cm−1 was assigned to the stretching vibration of \(\:\text{P}-{\text{O}}^{-}\) in \(\:{Q}^{0}\) units, the stretching vibration in \(\:{\text{P}\text{O}}_{3}^{2-}\) groups (\(\:{Q}^{1}\)), and the symmetric stretching vibrations of \(\:\text{P}-\text{O}-\text{P}\) \(\:{[\text{v}}_{\text{a}\text{s}}\left(\text{P}-\text{O}-\text{P}\right)]\) in the pyrophosphate units52,53. The weak shoulder at 1391 cm−1 is referred to the symmetric stretching vibrations of \(\:\text{P}=\text{O}\) bonds50,51,53. The bands observed in the higher energy region at 1667, 2381, 2942, and 3480 cm⁻¹ correspond to the bending vibrations of \(\:\text{H}-\text{O}-\text{H}\) and \(\:\text{P}-\text{O}\text{H}\) and the stretching vibration of \(\:\text{H}-\text{O}-\text{H}\) in H2O48,50. With the introduction of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+, no significant shift in the FTIR band positions was observed. This stability at these sites indicates that the strength and length of the bonds are not affected by environmental changes in the host glass network as a result of the introduction of these ions.

The thermal profiles of the fabricated PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, as shown in Fig. 3, reveal distinct exothermic peaks associated with crystallization temperatures and feature positions of glass transition temperatures. Table 3 presents the thermal parameters—glass transition temperature (\(\:{T}_{g}\)), onset crystallization temperatures (\(\:{T}_{C1}\) and \(\:{T}_{C2}\)), and maximum crystallization temperatures (\(\:{T}_{P1}\) and \(\:{T}_{P2}\))—which are derived from Fig. 3. The glass transition temperature of the PZBB host glass is 390 °C, as indicated in Table 3. The introduction of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ into the PZBB glass increases the glass transition temperature, suggesting enhanced network packing and cross-linking density. This observation aligns with the trends observed in the OPD and \(\:{V}_{t}\) behavior detailed in Table 3. The OPD and \(\:{V}_{t}\:\)contribute to a stronger, more rigid glass structure with increased connectivity. As a result, a higher thermal energy is required to transform solid glass into a viscous liquid, which indicates that glasses with higher OPD and \(\:{V}_{t}\) values within a given volume exhibit higher \(\:{T}_{g}\) values. Conversely, for the Ce3+-doped glass (PZBBCe3+), the crystallization temperatures shift to higher values, implying that Ce3+ ions improve the glass-forming ability and reduce tendency to crystallization. In contrast, Nd3+ and Ce3+/Nd3+-doped glasses (PZBBNd3+ and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+) show a shift in crystallization temperatures toward lower values, indicating a greater likelihood of crystallization and a diminished glass-forming ability. According to Table 3, the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses exhibit thermal stability and the presence of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions slightly decreases this stability. The slight reduction in thermal stability of PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses can be ascribed to various factors: (a) The introduction of Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions may disrupt the structural connectivity of the glass matrix, reducing its overall stability. However, this explanation is contradicted by the structural changes discussed earlier, which indicate an increase in connectivity within the studied glasses. (b) The incorporation of Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions, which have larger ionic radii, may introduce localized regions of structural disorder, lowering the temperature at which the material can remain amorphous. This increase in disorder is confirmed for Ce-based glasses (PZBBCe3+ and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+) as indicated by the Urbach energy results discussed later. However, for the Nd-based glass (PZBBNd3+), the structure shows a higher degree of order, making this interpretation inconsistent with the thermal stability behavior of the PZBBNd3+. (c) The inclusion of Nd3+ may introduce defects, such as oxygen vacancies or other structural irregularities, which can act as nucleation sites for crystallization, thereby lowering thermal stability. This interpretation is strongly supported by the observed shift in the crystallization temperature of the PZBBNd3+ glass to a lower value, indicating reduced stability of the glass phase. However, despite these minor reductions in thermal stability, the overall high thermal stability of glasses containing Ce3+ and Nd3+ remains intact and unaffected. This high thermal stability ensures the structural integrity of the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, prevents unwanted crystallization, which maintains high photoluminescent efficiency and enhances the longevity and durability of the red emitting materials.

Table 4 lists the behavior of various mechanical properties, including longitudinal\(\: ({\varvec{v}}_{\varvec{l}})\) and shear \(\:({\varvec{v}}_{\varvec{s}})\) velocities, along with elastic moduli such as longitudinal \(\:({C}_{11}),\) shear \(\:({C}_{44}),\), bulk (B), Young’s modulus (Y), and the Poisson’s ratio \(\:(\sigma).\) It also includes the microhardness (\(\:{H}_{UT}\)), acoustic impedance (\(\:{Z}_{i}\)), and Debye temperature (\(\:{\theta\:}_{D}\)). Initially, the variations in the obtained mechanical parameters were minor, as listed in Table 4, due to the slight increases in Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ contents. The elastic properties of glass materials are influenced primarily by factors such as the packing density, bond dissociation energy of metal-oxide bonds, cross-linking density, and coordination number. The addition of Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions increased the density and tightness of the proposed PZBB host glass, enhancing both the longitudinal and shear velocities. Furthermore, Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions played a significant role in filling network interstices and integrating into the glass network, which reduced the travel time of waves and consequently increased the ultrasonic velocity. The elastic moduli (longitudinal, shear, bulk, and Young) also follow a similar trend, increasing with the introduction of Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions, as indicated in Table 4. The increases in the microhardness (\(\:{H}_{UT}\)) and Debye temperature (\(\:{\theta\:}_{D}\)) further support the rigidity of the glasses and the observed elastic moduli results. The reduction in Poisson’s ratio (\(\:\sigma\:\)), as detailed in Table 4, reflects the increased cross-linking density due to the diffusion of Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions, which confirms the trends in the ultrasonic velocities and elastic moduli. Additionally, the increase in the acoustic impedance (\(\:{Z}_{i}\)), which denotes resistance to ultrasonic wave propagation, is attributed to the formation of PO4 chains and supports the compactness of the glass network.

Figure 4a displays the optical absorption spectra for the PZBB, PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses. The PZBB host glass shows no absorption bands, as noted in the inset of Fig. 4. In contrast, the spectra for the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses reveal several absorption bands, indicating the integration of Nd3+ and Ce3+ ions into the glass network. Ce-doped glasses typically exhibit absorption bands in the UV and blue regions due to \(\:4F\to\:5d\) transitions. In PZBBCe3+, bands appear at 206, 222, 232, 246, 260, 266, 274, 292, 302, 308, 316, 326, 338, 346, 360, and 376 nm. The bands at 206, 222, 232, and 246 nm correspond to the transition in the split 2\(\:{F}_{5/2}\to\:5{d}_{2}\) in Ce3+. The bands at 260 and 264 nm resulted from the charge transfer transitions in Ce4+. The bands at 274, 292, 302, 308, 316, 326, and 338 nm are attributed to the 2\(\:{F}_{5/2}\to\:5{d}_{1}\) transitions in the Ce3+ ion. The bands at 346, 360, and 376 nm correspond to the transition in the 2\(\:{F}_{7/2}\to\:5{d}_{1}\) of Ce3+ ion. For PZBBNd3+, bands are observed at 216, 230, 242, 250, 256, 262, 356, 528, 544, 744, and 806 nm. Nd3+ ions typically show absorption bands approximately \(\:\sim\)356, 432, 474, 515, 528, 586, 628, 684, 750, 806, and 882 nm, corresponding to various transitions from the 4I9/2 ground state to various excited states. Here, the bands at 356, 528, 544, 744, and 806 correspond to transitions from the Nd3+ ground state 4I9/2 to the excited state 4D3/2 + 4D3/2+4D1/2, 4G7/2, 4G5/2, 4S3/2, and 4F5/2+2H9/2. On the other hand, the bands that appeared in the region of 200–300 nm in the PZBBNd3+ glass arose from impurities, defects, and charge transfer. In PZBBCe3+-Nd3+, bands at 218, 240, 250, 262, 272, 284, 296, 302, 316, 326, 332, 342, 348, 354, 526, 584, 744, and 804 nm are observed as a result of transitions within Ce3+/Ce4+ and Nd3+ ions, indicating that the two ions were successfully integrated within the considered glass. Finally, it is important to note the presence of saturation or apparent cutoff in some absorption bands within the 200–400 nm range. These features, observed in the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+–Nd3+ glasses, do not correspond to the intrinsic UV absorption edge of the host matrix. This is evident from the PZBB host glass, which exhibits no significant absorption in this region (as shown in the inset of Fig. 4), confirming its transparency, and ruling out host-related artifacts. Instead, the absorption bands observed are attributed to the electronic transitions of the dopant ions, specifically Ce3+/Ce4+, Nd3+, impurities, defects, and charge transfer. These transitions are well-documented in this spectral region and account for the distinct and structured features in the spectra. Although the fundamental absorption edge of the glass matrix may begin to contribute at wavelengths shorter than 200 nm (not fully captured in the current data), the absorption features between 200 and 400 nm are associated with the dopants and not spectrometer-related artifacts.

By applying the Lambert-Beer law (Eq. 14) and analyzing the absorption spectra, the absorption coefficient (α) of the fabricated glasses was calculated11,17.

where, \(\:{I}_{o}\) and I represent the incident and transmitted photon intensities passing across the considered glasses of the thicknesses \(\:t\).

The optical band gap (\(\:{E}_{g}\)) of the considered glasses was calculated based on Tauc’s theory and the supporting research by Mott and Davis using the following Eqs11,17..

By constructing a Tauc plot of \(\:h\nu\:\) versus \(\:{\left(\alpha\:h\nu\:\right)}^{0.5}\), as shown in Fig. 4b, the indirect optical band gap (\(\:{E}_{g}\)) was inferred. The \(\:{E}_{g}\) values were determined by the slope of the linear region of the curve, where it intersects the \(\:h\nu\:\) axis, noting the \(\:h\nu\:\) value at αhν = 0.

The Urbach energies \(\:\left(\varDelta\:E\right)\) of the considered glasses were calculated using the equation from references13,19.

By applying Eq. 16, the relationship between \(\:h\nu\:\) and \(\:ln\alpha\:\) for the considered glasses was plotted, as shown in Fig. 4c. The Urbach energy \(\:\left(\varDelta\:E\right)\) was obtained by finding the reciprocal of the intersection point of the curve’s linear extension with the x-axis.

The PZBB host glass exhibited a band gap and an Urbach energy of 3.20 and 0.328 eV, as tabulated in the inset of Figs. 4b and c. The incorporation of Ce3+ into the PZBB network (PZBBCe3+ glass) led to a notable reduction in the optical band gap and an increase in the Urbach energy. The presence of Ce3+ ions within the PZBB host glass generates localized states within the band gap, which promotes easier electronic transitions. This not only lowers the optical band gap but also increases structural disorder, broadening the density of states tail and thereby raising the Urbach energy. These changes result from the ion’s effects on the glass network, free carriers’ introduction, and defect states’ creation. Unlike Ce3+, Nd3+ (glass PZBBNd3+) slightly reduces the band gap and sharply reduces the Urbach energy. Nd3+ has a \(\:{4f}^{4}\) electron configuration, and its electronic transitions typically involve intra-configurational 4f – 4f transitions, which are more localized than the conduction band electrons. Introducing Nd3+ ions into the glass network does not significantly disrupt the electronic structure but can induce subtle changes that slightly lower the optical band gap. The effect is small because Nd3+ does not introduce many defect states or new energy levels within the band gap. Nd3+ ions also tend to form more stable and ordered coordination environments within the glass matrix, which reduces structural disorder. As the glass network becomes more stable and less disordered, the density of states near the conduction band edge sharpens, and the tail of the density of states responsible for the Urbach energy narrows, resulting in a decrease in the Urbach energy. In the PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass, a balance between the effects of Ce3+ and Nd3+ is observed, as the glass exhibits an optical band gap that is higher than that of the PZBBCe3+ glass but lower than that of the PZBBNd3+ glass. Corresponding changes in the gap energy are also evident, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4c. This balance arises from the combined influence of the cerium and neodymium ions.

Based on the band gap results, the refractive index was determined using the following Eqs19,43. and is provided in the inset table of Fig. 4c.

The PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses all exhibited higher refractive indices than the PZBB host glass. The PZBBCe3+ glass had the highest refractive index, while PZBBNd3+ had the lowest. The PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass showed a refractive index that is relatively balanced between the two. Compared to the PZBB host glass, the higher refractive indices of the PZBBCe3+ and PZBBNd³⁺ glasses can be attributed to the higher polarizability of Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions. The higher refractive index of PZBBCe3+, compared to PZBBNd3+, is likely due to the larger ionic radius of Ce3+ and its more diffuse electron cloud, leading to higher polarizability and, consequently, a higher refractive index. The balanced refractive index in the PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass results from the combined polarizabilities of the two ions, producing an intermediate value between those of the individual Ce3+ and Nd3+ glasses.

The spectroscopic characteristics and photoluminescent parameters of produced materials are further examined using Judd–Ofelt (JO) theory. This theory is applied to extensively investigate the electric dipole transitions within the \(\:4f\) configuration of RE³⁺ ions in various host media54. For optical transitions involving both Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions, the experimental oscillator strength (\(\:{f}_{exp}\)) and the calculated oscillator strength (\(\:{f}_{cal}\)) for each absorption transition were determined using Eqs. 18 and 19, respectively54,55,56.

Here, the \(\:m\) & \(\:e\), \(\:c\), and \(\:N\) are the electron mass & charge, speed of light, and Avogadro’s number. The \(\:\epsilon\:\left(\nu\:\right)\) represent the he molar absorption coefficient of absorption band corresponding to the energy \(\:\nu\:\) (cm−1) and \(\:d\nu\:\) is the half bandwidth. The value of \(\:\epsilon\:\left(\nu\:\right)\) deduce based on Beer–Lambert, as follows

Where, \(\:C\), \(\:l\), and \(\:\text{log}\left(\frac{{I}_{o}}{I}\right)\) represent the rare-earth ion concentration, the thickness of the glass sample, and the optical density.

Where, \(\:n\) and \(\:J\:\)represent the refractive index of the medium and the total angular momentum of the ground state. \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{\lambda\:}\) (\(\:\lambda\:=2,\:4,\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:6\)) and \(\:{U}^{\lambda\:}\) are \(\:\text{J}-\text{O}\) intensity parameters and the doubly reduced matrix elements of the unit tensor operator evaluated in the intermediate coupling scheme for a transition \(\:{\Psi\:}J{\to\:{\Psi\:}}^{{\prime\:}}{J}^{{\prime\:}}\).

The peak positions of the absorption bands, along with their corresponding transitions and the derived values of \(\:{f}_{exp}\) and \(\:{f}_{cal}\), are presented in Table 5. It is important to note that in the case of Ce³⁺, multiple absorption bands were observed for each transition due to energy level splitting. To represent the possible transitions, only three characteristic wavelengths were selected for oscillator strength calculations, as shown in Table 5.

The results obtained for the experimental and calculated oscillator strengths demonstrated good convergence. The notable differences in oscillator strengths observed for both Ce³⁺ and Nd³⁺ in the co-doped PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass, compared to their singly doped counterparts (PZBBNd3+ and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+), provide strong evidence for interactions between the two ions within the glass matrix. These Ce3+–Nd3+ interactions can alter the local crystal field environment, thereby modifying both ions’ energy level structure and transition probabilities. Such modifications may arise from mechanisms such as energy transfer between Ce3+ and Nd3+ or changes in site symmetry and bonding characteristics within the glass network. Higher oscillator strengths for specific transitions were observed, indicating increased absorption efficiency at those wavelengths, which is crucial for photoluminescent systems. For instance, the absorption of Ce3+ near 274 nm and Nd3+ around 744 nm suggests these wavelengths are optimal for excitation, potentially facilitating effective energy transfer process.

Table 6 presents the Judd–Ofelt (J–O) intensity parameters (\(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{2}\), \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{4}\), and \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{6}\)) and their trends for PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses. In PZBBCe3+ glass, the relatively high \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{2}\) indicates a highly asymmetric local environment and significant \(\:\text{C}\text{e}-\text{O}\) covalency. The lower \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{4}\) and \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{6}\) values suggest that asymmetry (linked to \(\:{{\Omega}}_{2}\)) primarily governs transition intensities. The trend \(\:{{\Omega}}_{2}>{{\Omega\:}}_{6}>{{\Omega\:}}_{4}\) confirms the dominance of odd-parity crystal field components. In PZBBNd3+, \(\:{{\Omega}}_{2}\) is lower than in the Ce³⁺-doped glass, suggesting a more symmetric environment or weaker \(\:\text{N}\text{d}-\text{O}\) covalency. However, both \(\:{{\Omega}}_{4}\) and especially \(\:{{\Omega}}_{6}\) are significantly higher, with \(\:{{\Omega}}_{6}\:\)being crucial for transitions from the 4F3/2 level— an essential factor in optimizing photoluminescence efficiency for practical applications. The typical trend \(\:{{\Omega}}_{2}>{{\Omega}}_{6}>{{\Omega}}_{4}\:\)reflects the strong role of higher-order crystal field effects. In PZBBCe3+-Nd3+, co-doping alters the J–O parameters for both ions. The reduced \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{2}\) suggests increased symmetry or altered covalency due to ion interaction. \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{4}\) increases markedly, indicating enhanced influence of even-parity fields, while \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{6}\) decreases compared to Nd3+-only glass but remains above the Ce3+-only level. The new trend \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{4}>{{\Omega\:}}_{2}>{{\Omega\:}}_{6}\:\)highlights significant changes in the glass structure and local ion environments, with \(\:{{\Omega\:}}_{4}\)-driven transitions becoming more dominant.

Figure 5 shows the red emission beam from the proposed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, when pumped with 308 nm light. Initially, no emission was observed from the PZBB host glass, as shown in Fig. 5a. The absence of emission from the PZBB host glass network suggests that none of the components typically responsible for photoluminescence are present—this includes both key elements like bismuth, which is well known for its luminescent properties, as well as any luminescent impurities that might otherwise be present. Initially, although the Ce3+ ion is best known as an emitter in the UV and blue light regions, some earlier studies have also reported red emissions from Ce3+ ions in different host matrices. Hasegawa et al.57 observed a broad reddish-yellow emission band spanning 500 to 750 nm in the BaCa2(Y0.998Ce0.002)6O12 phosphor, attributing it to a spin-allowed \(\:5\text{d}\:\to\:\:4\text{f}\) transition in Ce3+. Li et al.58 reported emission band extending from 400 to 700 nm in the Ba9Lu2Si6O24:Ce3+ phosphor, originating from \(\:5\text{d}\:\to\:\:4\text{f}\) transitions of Ce3+ ions located on Lu3+ sites. Finally, Kulesza et al.59 observed a well-defined red emission band centered at 650 nm in SrSO4:Ce powders, attributed to the spin-orbit splitting of the Ce3+ ground state into the 2F5/2 and 2F7/2 states, with the emission arising from transitions between these levels. On the other hand, regarding the red emission from Nd³⁺ ions, Nd³⁺ is widely known for its near-infrared (NIR) luminescence60,61,62, but there are also some reports of red emission from this ion. Balda et al.63 observed several red emission bands at 646, 656, 673, 675, and 686 nm from Nd³⁺ in a PB crystal, which were attributed to 4G11/2\(\:\to\:\)4I15/2, 4G9/2 \(\:\to\:\)4I13/2, 2G9/2 \(\:\to\:\)4I15/2, 4G9/2 \(\:\to\:\)4I13/2, 4G7/2 \(\:\to\:\)4I13/2, and 4G5/2 \(\:\to\:\)4I11/2 transitions, respectively. Additionally, Gaurkhede et al.64 reported an emission band at 654 nm, which they attributed to the 4F9/2 → 4I9/2 transition.

When the PZBBCe3+ and PZBBNd3+ glasses are pumped at 308 nm, the 5d3 and 2D7/2 energy levels of Ce3+ and Nd3+, respectively, are excited through the ground state absorption (GSA) mechanism. For Ce3+, the excited 3 d state nonradiatively decays to the 5d1 level, which then undergoes radiative decay to the 2F5/2 and 2F7/2 levels, emitting red light at 619 and 639 nm, as depicted in Fig. 6a. In the case of PZBBNd3+, the excited 2D7/2 state nonradiatively decays to the 2H11/2 and 4F9/2 levels before ultimately decaying to the 4I9/2 ground state, emitting red light at 616 and 677 nm, as shown in Fig. 6b. In comparison, the two red peaks formed in the PZBBCe3+glass had somewhat similar intensities, whereas in the PZBBNd3+glass, one of the bands had a higher intensity than the other, as observed in Figs. 5b and c, which occurred due to Stokes shift and the impact of the crystal field environment or the defects on Nd3+ emission. In PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass, single red light at 626 nm was generated, as shown in Fig. 5d, due to radiative decay from Ce3+ and Nd3+ and energy transfer between Ce3+ and Nd3+, as shown in Fig. 6c. The appearance of only one emission band in the PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass may be due to the energy transfer mechanism and spectral overlap.

As shown in Fig. 6c, there are two possible excitation pathways at 308 nm: one for Ce3+, from the ground state 2F5/2 to the highest excited state 5d4, and another for Nd3+, from the ground state 4I9/2 to the excited state 2D7/2. Three possible processes following this excitation led to red emission at 626 nm, as outlined below:

-

1.

Ce3+ may undergo nonradiative decay from the 5d4 excited state to the 5d1 state, followed by radiative decay to the ground state (2F5/2), resulting in red emission at 626 nm (as depicted in the right section of Fig. 6c).

-

2.

Nd3+ may experience nonradiative decay from the 2D7/2 excited state to the 2H11/2 state, followed by radiative decay to the ground state (4I9/2), also leading to red emission at 626 nm (as shown in the left section of Fig. 6c).

-

3.

Key feature of Fig. 6c illustrates the nonradiative energy transfer between Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions. This energy transfer, driven by mechanisms such as dipole-dipole or exchange interactions, takes place when there is adequate overlap between the donor’s (Nd3+ or Ce3+) emission spectrum and the acceptor’s (Nd3+ or Ce3+) absorption spectrum, coupled with a small interionic distance. Specifically, energy transfer can occur from the 5d3 state of Ce3+ to the 2H11/2 state of Nd3+, or from the 2D7/2 state of Nd3+ to the 5d1 state of Ce3+, followed by radiative emission at 626 nm due to the transition to the ground state 2F5/2 (Ce3+) and 4I9/2 (Nd3+).

Finally, it is worth noting that the probability of energy transfer from Nd3+ to Ce3+ is significantly lower than the transfer from Ce3+ to Nd3+. This makes Ce3+ a strong candidate as a sensitizer for Nd3+. Ce3+ efficiently absorbs UV and blue light and exhibits fast relaxation dynamics. Moreover, its excited states lie at higher energies compared to those of Nd3+, allowing for an energetically favorable (downhill) transfer. In contrast, energy transfer from Nd3+ to Ce3+ is inefficient, as it would require an energetically uphill process9,26,65.

To closely evaluate the red emission potential of the fabricated PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, detailed analysis of the absorption cross section \(\:\left({\sigma\:}_{abs.}\right(\lambda\:\left)\right)\), emission cross section (\(\:{\sigma\:}_{em.}\left(\lambda\:\right))\), and gain \(\:G\left(P,\:\lambda\:\right)\:\)cross sections were calculated using Eqs. 20, 21, 22. These parameters provide critical insight into the light absorption and emission capabilities of the materials, as well as their potential for optical amplification—key factors in determining their suitability for laser and photonic applications in the red spectral region

where, \(\:O.D\:\left(\lambda\:\right)\) is the optical density at wavelength \(\:\lambda\:\), \(\:t\) is glass samples thickness, and \(\:{N}^{{RE}^{3+}}\) denotes the concentration of the studied rare-earth ions (here Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions). \(\:\epsilon\:\) represents the excitation energy for Ce3+: 2F5/2 →5d1 (16155 cm−1), Ce3+: 2F7/2→5d1 (15649 cm−1), Nd3+: 4I9/2 →2H11/2 (16223 cm−1), and Nd3+: 4I9/2 →4F9/2 (14771 cm−1). \(\:h\) and \(\:k\) are the Plank and Boltzmann constants, respectively, and T is the ambient temperature. P represents the population inversion, where P is in the range of 0 to 1.

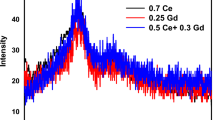

Figure 7 illustrates the absorption and emission cross sections of the PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses. As shown in Fig. 7a, the PZBBNd3+ glass exhibits two prominent absorption peaks with cross section values of \(\:8.319\times10^{-19}\) cm² at 616 nm and \(\:1.7482\times10^{-19}\) cm² at 677 nm. These related to the Nd3+: 4I9/2 →2H11/2 and 4I9/2→ 4F9/2 transitions, respectively. The PZBBCe3+ glass shows two absorption bands centered at 619 nm and 639 nm, with cross sections of \(\:8.882\times10^{-19}\) cm² and \(\:1.1328\times10^{-19}\) cm², respectively. These are attributed to Ce3+: 2F5/2→5d1 and 2F7/2→5d1 transitions. The relatively broad nature of these bands is characteristic of 4f →5d transitions in Ce3+, which are highly sensitive to the local crystal field environment provided by the glass matrix. In the PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass, a single absorption peak is observed at 626 nm with a cross section of \(\:4.9\times10^{-20}\) cm² (inset of Fig. 7a). This feature likely arises from overlapping contributions of both the Nd3+: 4I9/2 →2H11/2 and Ce3+: 2F5/2→5d1 transitions, indicating potential spectral overlap and interaction between the dopants. The PZBBCe3+ glass exhibits broad emission bands near 619 nm and 639 nm, characteristic of the Ce3+: 5 d → 4f transitions, as shown in Fig. 7b. These broad emissions in the red spectral region confirm that Ce3+ can function as an efficient red emitting center when excited at higher energies (typically in the UV range). The spectral broadness also suggests a significant impact of the host glass on the Ce3+ emission characteristics. For the PZBBNd3+ glass, two emission peaks are detected at 616 nm and 677 nm, as shown in Fig. 7c, corresponding to radiative transitions from higher excited states of Nd3+ to lower-energy states, particularly 2H11/2 →4I9/2 and 4F9/2 →4I9/2, respectively. The strong emission around 677 nm is particularly noteworthy for its relevance to red emitting photonic applications. The PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass displays a broad emission band around 626 nm (Fig. 7d), overlapping with the emission features of both singly doped Ce3+ and Nd3+ glasses. This suggests simultaneous luminescence from both dopants. The observed spectral features suggest potential energy transfer interactions between Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions, enhancing or modifying the overall emission characteristics.

Figure 8 presents the gain cross section spectra of PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, evaluated across different population inversion levels (P). For PZBBCe3+, the gain cross section is negative (indicative of absorption) at both 619 and 639 nm at P = 0. As P increases, the gain becomes positive around 619 and 639 nm, corresponding to Ce3+ emission bands. At P = 1, significant gain is observed, demonstrating the suitability of Ce3+ for broadband red luminescence. In PZBBNd3+, gain profiles show broad and sharp peaks at 616 and 677 nm, respectively. These match Nd3+ emission transitions and become increasingly positive with higher P, suggesting strong potential for red emission action at discrete red wavelengths, suitable for narrow-linewidth photoluminescence applications. The PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass exhibits a complex gain profile combining features of both ions. A broad gain region centered around 626 nm is primarily attributed to Ce3+, with narrower peaks overlaying from Nd3+. As P increases, gain enhancement suggests the possibility of dual-ion emission or energy transfer-driven Nd3+ dominance, depending on excitation conditions and population dynamics. At a population inversion level of P = 0.8, all studied glasses exhibit a noticeable dip, turning negative, in the gain cross-section, as shown in Fig. 8. This indicates net absorption rather than gain and points to a complex interplay of underlying mechanisms affecting Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions. This trend is primarily attributed to excited state absorption (ESA), where a significant fraction of Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions in the excited state may absorb additional photons to reach higher energy levels. It can suppress the net gain when ESA is strong at specific wavelengths, such as around 625 nm. Furthermore, changes in population distribution among Stark sublevels with varying P can alter transition probabilities, impacting the gain spectrum. Interactions between Ce3+ and Nd3+ ions and the PZBB glass matrix may also enhance absorption under partial inversion, particularly in the inter-peak region. Overall, the observed non-monotonic gain behavior at P = 0.8 reflects the combined effects of ESA, incomplete inversion, Stark sublevel dynamics, and host matrix influence.

Finally, all three glasses demonstrate potential for red emission under adequate population inversion. Ce3+ provides broad gain bandwidth, ideal for tunable sources, while Nd3+ offers spectrally selective gain. The PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass presents opportunities for tailored emission behavior through ion interaction and energy transfer mechanisms.

Conclusion

In summary, three developed glasses containing 1 mol% of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions as red emission (PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, or PZBBCe3+-Nd3+) were fabricated and characterized. The proposed Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions were incorporated into a host glass with a chemical composition of 50P2O5−20ZnO-20Bi2O3−10BaO (PZBB). In terms of thermal stability, all the examined glasses demonstrated notable thermal stability. The elastic moduli—Young’s, bulk, shear, and longitudinal modulus—as well as hardness, slightly improved due to the diffusion of the Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions into the PZBB host network. In terms of optical properties, the incorporation of Ce3+, Nd3+, or Ce3+/Nd3+ ions into the glass network was confirmed by their distinct absorption bands in the UV-Vis-NIR region. The developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses exhibited high thermal stability and elasticity. Upon excitation at 308 nm, the fabricated PZBBCe3+ glass has two strong characteristic red emission peaks at 619 and 639 nm, whereas the PZBBNd3+ has a highly intense red peak at 677 nm and a lower peak at 616 nm. On the other hand, PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ exhibited a single red peak at 626 nm. Comprehensive oscillator strength, Judd–Ofelt, and gain cross section analyses demonstrate the potential of developed PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, and PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses for red emitting photonic applications. The PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glass enables broadband, dual-ion emission with possible Ce3+→ Nd3+energy transfer, while the singly doped glasses offer broad (Ce3+) or narrow (Nd3+) gain—ideal for tunable red light sources. Therefore, the suitable mechanical and thermal properties, combined with highly efficient emissions in the red region of the studied PZBBCe3+, PZBBNd3+, or PZBBCe3+-Nd3+ glasses, make them strong candidates for use in optoelectronic devices such as red lasers, tunable light sources, and amplifiers. However, further investigations on emission lifetime and quantum efficiency should be conducted in the future to explore to fully evaluate photoluminescence performance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rajaramakrishna, R., Intachai, N., Kothan, S., Prongsamrong, P. & Kaewkhao, J. Red emission material from Eu3+ ion doped in oxy-fluoroborate glass system. Spect. Acta Part. A: Mole Biom Spect. 295, 122599 (2023).

Hong, K. S. et al. Red-emission properties and crystallization behavior in Eu2O3-TeO2 glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solid. 505, 400–405 (2019).

Kaur, H., Jayasimhadri, M., Sahu, M. K., Rao, P. K. & Reddy, N. S. Synthesis of orange emitting Sm3+ doped sodium calcium silicate phosphor by sol-gel method for photonic device applications. Ceram. Int. 46, 26434–26439 (2020).

Rao, A. S. Tunable photoluminescence studies of KZABS: RE3+ (RE3+= Tm3+, Tb3+ and Sm3+) glasses for w-LEDs based on energy transfer. J. Lumin. 251, 119194 (2022).

Dong, L., Zhang, S., Gong, P., Kang, L. & Lin, Z. Evaluation and prospect of Mid-Infrared nonlinear optical materials in \(\:{f}^{0}\) rare earth (RE = Sc, Y, La) chalcogenides. Coord. Chem. Rev. 509, 215805 (2024).

Saeed, A. et al. Glass materials in nuclear technology for gamma ray and neutron radiation shielding: a review. Nonlinear Opt. Quantum Optics: Con Mod. Opt. 53, 107–159 (2020).

Abu-Raia, W. A., Aloraini, D. A., El-Khateeb, S. A. & Saeed, A. Ni ions doped oxyflourophosphate glass as a triple ultraviolet–visible–near infrared broad bandpass optical filter. Sci. Rep. 12, 16024 (2022).

Ma, N. et al. Near-pure red emission of highly thermally stable Eu3+ doped multi-component transparent oxyfluoride aluminosilicate glass-ceramic for red lasers and trichromatic WLEDs. Cera Inter. 50 (22), 45052–45063 (2024).

Samuel, P. et al. Efficient energy transfer between Ce3+ and Nd3+ in cerium codoped nd: YAG laser quality transparent ceramics. J. Alloy Comp. 507 (2), 475–478 (2010).

Saeed, A., Sobaih, S., Abu-raia, W. A., Abdelghany, A. & Heikal, S. Novel Er3 + doped heavy metals-oxyfluorophosphate glass as a blue emitter. Opt. Quantum Electron. 53, 482 (2021).

Faleiro, J. H. et al. Niobium incorporation into rare-earth doped aluminophosphate glasses: structural characterization, optical properties, and luminescence. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 605, 122173 (2023).

Francini, R., Giovenale, F., Grassano, U. M., Laporta, P. & Taccheo, S. Spectroscopy of Er and Er–Yb-doped phosphate glasses. Opt. Mater. 13, 417–425 (2000).

El-Batal, A. M., Saeed, A., Hendawy, N., El-Okr, M. & El-Mansy, M. K. Influence of mo or/and Co ions on the structural and optical properties of phosphate zinc lithium glasses. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 559, 120678 (2021).

Brow, R. K. The structure of simple phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 263, 1–28 (2000).

Aloraini, D. A., Almuqrin, A. H. & Saeed, A. Impact of Bi3+, Ba2+, and Pb2+ ions on the structural, thermal, mechanical, optical, and gamma ray shielding performance of borosilicate glass. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56, 126 (2024).

Qian, L., Wang, R. & Wang, W. Broad emission in Bi-doped GeGaSe chalcogenide glass and glass-ceramic. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 643, 123177 (2024).

Taha, E. O. & Saeed, A. The effect of cobalt/copper ions on the structural, thermal, optical, and emission properties of erbium zinc lead Borate glasses. Sci. Rep. 13, 12260 (2023).

El-Khateeb, S. A. & Saeed, A. Impact of ligands on the performance of band-stop and bandpass optical filter of Cobalt sodium zinc Borate glass. Opt. Quantum Electron. 55, 759 (2023).

Saeed, A. Elastic, transparent, and thermally stable Borate glass reinforced by barium as an efficient gamma ray attenuator. Mater. Today Commun. 38, 108361 (2024).

Francisco-Rodríguez, H. I., Soriano-Romero, O., Meza-Rocha, A. N. & Caldiño, U. Sodium zinc phosphate glasses doped with Tb3 + and Tb3+/Eu3 + as multicolor phosphor for green laser stimulated emission and WLED applications. Opt. Mater. 147, 114776 (2024).

Huerta, E. F., Soriano-Romero, O., Meza-Rocha, A. N., Caldiño, U. & Multicolor emission in potassium-zinc phosphate glasses activated with Dy3+, Tb3+ and Dy3+/Tb3+ for photonic device applications. J. Luminesc. 257, 119617 (2023).

Yi, L. et al. Enhancement of red emission in Ce3+, RE3+, Mn2+ codoped Ca5 (BO3) 3F phosphors: luminescent properties and structural refinement. J. Alloys Compd. 688, 345–353 (2016).

Efimov, A. M., Ignat’ev, A. I., Nikonorov, N. V. & Postnikov, E. S. Spectral components that form UV absorption spectrum of Ce3+ and Ce (IV) Valence States in matrix of photothermorefractive glasses. Opt. Spectrosc. 111, 426–433 (2011).

Ramachari, D., Moorthy, L. R. & Jayasankar, C. K. Optical absorption and emission properties of Nd3+-doped oxyfluorosilicate glasses for solid state lasers. Infrared Phys. Technol. 67, 555–559 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Sensitization and deactivation effects of Nd3+ on the Er3+: 2.7 µm emission in PbF2 crystal. Opt. Mater. Expr. 9 (4), 1698–1708 (2019).

Li, Y., Zhou, S., Lin, H., Hou, X. & Li, W. Intense 1064 Nm emission by the efficient energy transfer from Ce3+ to Nd3+ in ce/nd co-doped YAG transparent ceramics. Opt. Mater. 32 (9), 1223–1226 (2010).

Aloraini, D. A., Gohra, H. A. & Saeed, A. Adjusting the cool white light emission in Borate glass by controlling Ce3+/Cr3+ energy transfer for white light-emitting diodes and outdoor lighting. Phys B: Cond Matter 700, 416954 (2025).

dos Reis, G. S. et al. Uptake the rare Earth elements nd, ce, and La by a commercial diatomite: kinetics, equilibrium, thermodynamic and adsorption mechanism. J. Molec Liqu. 389, 122862 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. An industrial mixed rare-earth oxide fuel cell with low cost and high electrochemical performance. Ceram. Inter. 50 (7), 10007–10015 (2024).

Ueda, J. & Tanabe, S. Visible to near infrared conversion in Ce3+–Yb3+ Co-doped YAG ceramics. J Appl. Phys 106(4), 043101 (2009).

Samanta, T., Sarkar, S., Adusumalli, V. N., Praveen, A. E. & Mahalingam, V. Enhanced visible and near infrared emissions via Ce3+ to Ln3+ energy transfer in Ln3+-doped CeF3 nanocrystals (Ln = Nd and Sm). Dalt Trans. 45 (1), 78–84 (2016).

Zhang, L., Hu, L. & Jiang, S. Progress in Nd3+, Er3+, and Yb3+ doped laser glasses at Shanghai Institute of optics and fine mechanics. Inter J. Appl. Glass Scie. 9 (1), 90–98 (2018).

Mikalauskaite, I. et al. Temperature induced emission enhancement and investigation of Nd3+→ Yb3+ energy transfer efficiency in NaGdF4: Nd3+, Yb3+, Er3+ upconverting nanoparticles. J. Lumi. 223, 117237 (2020).

Alzahrani, J. S. et al. Optical and radiation absorption properties of bismuth-borate glasses doped with Ce4+, Nd3+, and Sm3+. Optik 274, 170510 (2023).

Lin, Y. et al. CaLu2Mg2Si3O12: Ce3+, Cr3+, Nd3+ Phosphor-In‐Glass Film for Laser‐Driven Ultra‐Broadband Near‐Infrared Lighting with Watt‐Level Output. Laser & Photonics Reviews https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202400995 (2024).

Quang, N. D. et al. Effects of alkali ions on luminescence and scintillation performance of Ce3 + doped phosphate glasses for radiation detection. Ceram. Int. 49, 28711–28719 (2023).

Singh, H. et al. Up-conversion and downconversion studies of Nd3+ doped borophosphate glasses. Opt. Mater. 137, 113586 (2023).

Manasa, P., Srihari, T., Basavapoornima, C., Joshi, A. S. & Jayasankar, C. K. Spectroscopic investigations of Nd3+ ions in Niobium phosphate glasses for laser applications. J. Luminesc. 211, 233–242 (2019).

Meng, J. X. et al. Fluorescence properties of novel near-infrared phosphor CaSc2O4: Ce3+, Nd3+. J. Alloy Comp. 508 (1), 222–225 (2010).

Tai, Y., Zheng, G., Wang, H. & Bai, J. Near-infrared quantum cutting of Ce3+–Nd3+ co-doped Y3Al5O12 crystal for crystalline silicon solar cells. J. Photo Photo A: Chem. 303, 80–85 (2015).

AitMellal, O. et al. Structural properties and near-infrared light from Ce3+/Nd3+-co-doped LaPO4 nanophosphors for solar cell applications. J. Mater. Science: Mater. Elect. 33 (7), 4197–4210 (2022).

Almulhem, N., Awada, C. & Shaalan, N. M. Photocatalytic degradation of phenol red in water on Nb (x)/TiO2 nanocomposites. Crystals 12, 911 (2022).

Zeed, M. A., Saeed, A., El Shazly, R. M., El-Mallah, H. M. & Elesh, E. Double effect of glass former B2O3 and intermediate Pb3O4 augmentation on the structural, thermal, and optical properties of Borate network. Optik 272, 170368 (2023).

Aloraini, D. A., Abu-raia, W. A. & Saeed, A. An efficient attenuator for gamma rays and slow neutrons of elastic and transparent lead sodium zinc calcium Borate glass. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56, 340 (2024).

Gaafar, M. S., Afifi, H. A. & Mekawy, M. M. Structural studies of some phospho-borate glasses using ultrasonic pulse–echo technique, DSC and IR spectroscopy. Phys. B. 404, 1668–1673 (2009).

Zeed, M. A., Shazly, E., Elesh, R. M., El-Mallah, E., Saeed, A. & H. M. & Dual effect of B3 + and Pb2 + ions on the elasticity and semiconducting nature of sodium zinc Borate glass. Glass Phys. Chem. 49, 593–603 (2023).

Stoch, P., Stoch, A., Ciecinska, M., Krakowiak, I. & Sitarz, M. Structure of phosphate and iron-phosphate glasses by DFT calculations and ftir/raman spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 450, 48–60 (2026).

Abdelghany, A. M., ElBatal, F. H., ElBatal, H. A. & EzzElDin, F. M. Optical and FTIR structural studies of CoO-doped sodium borate, sodium silicate and sodium phosphate glasses and effects of gamma irradiation-a comparative study. J. Mol. Struct. 1074, 503–510 (2014).

Seshadri, M., Batesttin, C., Silva, I. L., Bell, M. J. V. & Anjos, V. Effect of compositional changes on the structural properties of borophosphate glasses: ATR-FTIR and Raman spectroscopy. Vibr Spectrosc. 110, 103137 (2020).

Kumar, M., Vijayalakshmi, R. P. & Ratnakaram, Y. C. Investigation of emission characteristics in Er3+-doped bismuth phosphate glasses for NIR laser materials. Spectrochim Acta A. 302, 123096 (2023).

Al-Ghamdi, H. et al. Fabrication, structure, physical properties and FTIR spectroscopy of zirconate doped-borophosphate bioglasses. Opt. Quantum Electron. 55, 1025 (2023).

Sebak, M. A., Guizani, I., Gami, F., Mostafa, M. & Mostafa, M. M. Photoluminescence and fourier transform infrared spectral studies of varying levels of manganese doping in zinc phosphate oxide glasses. J. Electron. Mater. 52, 4551–4557 (2023).

El Jouad, M., Gaumer, N., Siniti, M., Touhtouh, S. & Hajjaji, A. Structural, physical, thermal and optical spectroscopy studies of the europium doped strontium phosphate glasses. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 151, 110563 (2023).

Hehlen, M. P., Brik, M. G. & Krämer, K. W. 50th anniversary of the Judd–Ofelt theory: an experimentalist’s view of the formalism and its application. J. Lumi. 136, 221–239 (2013).

Reddy, C. M. et al. D. P. Absorption and fluorescence studies of Sm3+ ions in lead containing sodium fluoroborate glasses. J. Lumi. 131 (7), 1368–1375 (2011).

Asirvadam, A. et al. Optical and luminescence properties of Er3+ doped Sb2O3–Li2O–MO (M = Mg, Ca and Sr) glasses. Opti Mater. 128, 112422 (2022).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Blue-light-pumped wide-band red emission in a new Ce3+-activated oxide phosphor, BaCa2Y6O12: Ce3+: melt synthesis and photoluminescence study based on crystallographic analyses. J. Alloy Comp. 797, 1181–1189 (2019).

Li, N. et al. Red shifts, intensity enhancements and abnormally thermal quenching of Ba9Lu2Si6O24: Ce3+ emission by nitridation. J. Lumi. 214, 116587 (2019).

Dagmara, K., Joanna, C., Luis, S., Zoila, B. & Eugeniusz, Z. Anomalous red and infrared luminescence of Ce3+ ions in srs: Ce sintered ceramics. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119 (49), 27649–27656 (2015).

Mahamuda, S. et al. Spectroscopic properties and luminescence behavior of Nd3+ doped zinc alumino bismuth Borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Soli. 74 (9), 1308–1315 (2013).

Mhlongo, M. R., Koao, L. F., Motaung, T. E., Kroon, R. E. & Motloung, S. V. Analysis of Nd3+ concentration on the structure, morphology and photoluminescence of sol-gel Sr3ZnAl2O7 nanophosphor. Resu Phys. 12, 1786–1796 (2019).

Tayal, Y. et al. Enhanced emission in the NIR range by Nd3 + doped borosilicate glass for lasing applications. Appl. Phys. B. 130 (9), 157 (2024).

Balda, R., Fernändez, J., Nyein, E. E. & Hömmerich, U. Infrared to visible upconversion of Nd3+ ions in KPb2Br5 low phonon crystal. Optic Expr. 14 (9), 3993–4004 (2006).

Gaurkhede, S. G., Khandpekar, M. M., Pati, S. P. & Singh, A. T. Red fluorescence in doped LaF3: Nd3+, Sm3+ nanocrystals synthesized by microwave technique. Inter Schol Rese Noti. 2012 (1), 763048 (2012).

Wang, Q. et al. Optical properties of Ce. co-doped YAG Nanopart. Visual near-infrared Biol. Imaging Spect. Acta Part. A: Mole Biom Spec. 149, 898–903 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU250374].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K.A wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almulhem, N.K. Intense red emission from highly elastic and thermally stable phosphate glass doped with Ce3+, Nd3+, and Ce3+/Nd3+ ions. Sci Rep 15, 22545 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05813-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05813-4